“An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” was passed by the Pennsylvania Assembly on March 1, 1780 (Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, public domain).

The elimination of slavery in the United States of America has been a lengthy and less than perfect process, beginning with early abolition efforts which occurred during the nation’s colonial period, and which were designed to reduce and ultimately end the buying, selling, and exchanging or bartering of human beings. According to the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, “the first written protest in England’s American colonies came from Germantown Friends in 1688” in Pennsylvania; the Philadelphia Yearly Meeting of Friends also subsequently “criticized the importation of slaves in 1696, objected to slave trading in 1754, and in 1775 determined to disown members who would not free their slaves.”

That same year, America’s first abolition organization, the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage, was also established. Formed in Philadelphia on April 14, 1775, the organization became more commonly known as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society. “Throughout the 1700s,” according to PHMC historians, the Pennsylvania Assembly also actively “attempted to discourage the slave trade by taxing it repeatedly,” and then began taking a slightly more intense approach by passing “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery” by a vote of 34 to 21 on March 1, 1870. The first legislative action of its kind in America, it decreed, among other things, “that ‘every Negro and Mulatto child born within the State after the passing of the Act (1780) would be free upon reaching age twenty-eight,'” and that after their release from slavery, these freed people “were to receive the same freedom dues and other privileges ‘such as tools of their trade,’ as servants bound by indenture for four years.” Heavily opposed by German Lutherans and the representatives of counties with large populations of residents of German heritage, this new law still allowed residents of the Keystone State to continue to buy slaves who had already been registered, but prohibited Pennsylvanians from importing new slaves into the state.

* Note: Although a significant number of German Lutherans initially opposed the state’s 1870 abolition act, many German Methodists adopted anti-slavery positions, as did many who were considered to be “Forty-Eighters” (Germans who emigrated to America during or after the revolutions of 1848).

Although opponents of Pennsylvania’s new abolition law continued to challenge this legislation for several years after its passage, the legislation ultimately survived, and was subsequently strengthened in 1788 to stop Pennsylvanians residing near the borders of Delaware and Maryland from sneaking slaves into the state in violation of the law. The full wording of Pennsylvania’s initial abolition act read as follows:

When we contemplate our Abhorence of that Condition to which the Arms and Tyranny of Great Britain were exerted to reduce us, when we look back on the Variety of Dangers to which we have been exposed, and how miraculously our Wants in many Instances have been supplied and our Deliverances wrought, when even Hope and human fortitude have become unequal to the Conflict; we are unavoidably led to a serious and grateful Sense of the manifold Blessings which we have undeservedly received from the hand of that Being from whom every good and perfect Gift cometh. Impressed with these Ideas we conceive that it is our duty, and we rejoice that it is in our Power, to extend a Portion of that freedom to others, which hath been extended to us; and a Release from that State of Thraldom, to which we ourselves were tyrannically doomed, and from which we have now every Prospect of being delivered. It is not for us to enquire, why, in the Creation of Mankind, the Inhabitants of the several parts of the Earth, were distinguished by a difference in Feature or Complexion. It is sufficient to know that all are the Work of an Almighty Hand, We find in the distribution of the human Species, that the most fertile, as well as the most barren parts of the Earth are inhabited by Men of Complexions different from ours and from each other, from whence we may reasonably as well as religiously infer, that he, who placed them in their various Situations, hath extended equally his Care and Protection to all, and that it becometh not us to counteract his Mercies.

We esteem a peculiar Blessing granted to us, that we are enabled this Day to add one more Step to universal Civilization by removing as much as possible the Sorrows of those, who have lived in undeserved Bondage, and from which by the assumed Authority of the Kings of Britain, no effectual legal Relief could be obtained. Weaned by a long Course of Experience from those narrow Prejudices and Partialities we had imbibed, we find our Hearts enlarged with Kindness and Benevolence towards Men of all Conditions and Nations; and we conceive ourselves at this particular Period extraordinarily called upon by the Blessings which we have received, to manifest the Sincerity of our Profession and to give a substantial Proof of our Gratitude.

And whereas, the Condition of those Persons who have heretofore been denominated Negroe and Mulatto Slaves, has been attended with Circumstances which not only deprived them of the common Blessings that they were by Nature entitled to, but has cast them into the deepest Afflictions by an unnatural Separation and Sale of Husband and Wife from each other, and from their Children; an Injury the greatness of which can only be conceived, by supposing that we were in the same unhappy Case. In Justice therefore to Persons so unhappily circumstanced and who, having no Prospect before them whereon they may rest their Sorrows and their hopes have no reasonable Inducement to render that Service to Society, which they otherwise might; and also ingrateful Commemoration of our own happy Deliverance, from that State of unconditional Submission, to which we were doomed by the Tyranny of Britain.

Be it enacted and it is hereby enacted by the Representatives of the Freemen of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in General Assembly met and by the Authority of the same, That all Persons, as well Negroes, and Mulattos, as others, who shall be born within this State, from and after the Passing of this Act, shall not be deemed and considered as Servants for Life or Slaves; and that all Servitude for Life or Slavery of Children in Consequence of the Slavery of their Mothers, in the Case of all Children born within this State from and after the passing of this Act as aforesaid, shall be, an hereby is, utterly taken away, extinguished and for ever abolished.

Provided always and be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That every Negroe and Mulatto Child born within this State after the passing of this Act as aforesaid, who would in Case this Act had not been made, have been born a Servant for Years or life or a Slave, shall be deemed to be and shall be, by Virtue of this Act the Servant of such person or his or her Assigns, who would in such Case have been entitled to the Service of such Child until such Child shall attain unto the Age of twenty eight Years, in the manner and on the Conditions whereon Servants bound by Indenture for four Years are or may be retained and holden; and shall be liable to like Correction and punishment, and intitled to like Relief in case he or she be evilly treated by his or her master or Mistress; and to like Freedom dues and other Privileges as Servants bound by Indenture for Four Years are or may be intitled unless the Person to whom the Service of any such Child Shall belong, shall abandon his or her Claim to the same, in which Case the Overseers of the Poor of the City Township or District, respectively where such Child shall be so abandoned, shall by Indenture bind out every Child so abandoned as an Apprentice for a Time not exceeding the Age herein before limited for the Service of such Children.

And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That every Person who is or shall be the Owner of any Negroe or Mulatto Slave or Servant for life or till the Age of thirty one Years, now within this State, or his lawful Attorney shall on or before the said first day of November next, deliver or cause to be delivered in Writing to the Clerk of the Peace of the County or to the Clerk of the Court of Record of the City of Philadelphia, in which he or she shall respectively inhabit, the Name and Sirname and Occupation or Profession of such Owner, and the Name of the County and Township District or Ward where he or she resideth, and also the Name and Names of any such Slave and Slaves and Servant and Servants for Life or till the Age of thirty one Years together with their Ages and Sexes severally and respectively set forth and annexed, by such Person owned or statedly employed, and then being within this State in order to ascertain and distinguish the Slaves and Servants for Life and Years till the Age of thirty one Years within this State who shall be such on the said first day of November next, from all other persons, which particulars shall by said Clerk of the Sessions and Clerk of said City Court be entered in Books to be provided for that Purpose by the said Clerks; and that no Negroe or Mulatto now within this State shall from and after the said first day of November by deemed a slave or Servant for life or till the Age of thirty one Years unless his or her name shall be entered as aforesaid on such Record except such Negroe and Mulatto Slaves and Servants as are hereinafter excepted; the said Clerk to be entitled to a fee of Two Dollars for each Slave or Servant so entered as aforesaid, from the Treasurer of the County to be allowed to him in his Accounts.

Provided always, That any Person in whom the Ownership or Right to the Service of any Negro or Mulatto shall be vested at the passing of this Act, other than such as are herein before excepted, his or her Heirs, Executors, Administrators and Assigns, and all and every of them severally Shall be liable to the Overseers of the Poor of the City, Township or District to which any such Negroe or Mulatto shall become chargeable, for such necessary Expence, with Costs of Suit thereon, as such Overseers may be put to through the Neglect of the Owner, Master or Mistress of such Negroe or Mulatto, notwithstanding the Name and other descriptions of such Negroe or Mulatto shall not be entered and recorded as aforesaid; unless his or her Master or Owner shall before such Slave or Servant attain his or her twenty eighth Year execute and record in the proper County, a deed or Instrument securing to such Slave or Servant his or her Freedom.

And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That the Offences and Crimes of Negroes and Mulattos as well as Slaves and Servants and Freemen, shall be enquired of, adjudged, corrected and punished in like manner as the Offences and Crimes of the other Inhabitants of this State are and shall be enquired of adjudged, corrected and punished, and not otherwise except that a Slave shall not be admitted to bear Witness agaist [sic] a Freeman.

And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid That in all Cases wherein Sentence of Death shall be pronounced against a Slave, the Jury before whom he or she shall be tried shall appraise and declare the Value of such Slave, and in Case Such Sentence be executed, the Court shall make an Order on the State Treasurer payable to the Owner for the same and for the Costs of Prosecution, but in Case of a Remission or Mitigation for the Costs only.

And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid That the Reward for taking up runaway and absconding Negroe and Mulatto Slaves and Servants and the Penalties for enticing away, dealing with, or harbouring, concealing or employing Negroe and Mulatto Slaves and Servants shall be the same, and shall be recovered in like manner, as in Case of Servants bound for Four Years.

And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That no Man or Woman of any Nation or Colour, except the Negroes or Mulattoes who shall be registered as aforesaid shall at any time hereafter be deemed, adjudged or holden, within the Territories of this Commonwealth, as Slaves or Servants for Life, but as freemen and Freewomen; and except the domestic Slaves attending upon Delegates in Congress from the other American States, foreign Ministers and Consuls, and persons passing through or sojourning in this State, and not becoming resident therein; and Seamen employed in Ships, not belonging to any Inhabitant of this State nor employed in any Ship owned by any such Inhabitant, Provided such domestic Slaves be not aliened or sold to any Inhabitant, nor (except in the Case of Members of Congress, foreign Ministers and Consuls) retained in this State longer than six Months.

Provided always and be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That this Act nor any thing in it contained shall not give any Relief or Shelter to any absconding or Runaway Negroe or Mulatto Slave or Servant, who has absented himself or shall absent himself from his or her Owner, Master or Mistress, residing in any other State or Country, but such Owner, Master or Mistress, shall have like Right and Aid to demand, claim and take away his Slave or Servant, as he might have had in Case this Act had not been made. And that all Negroe and Mulatto Slaves, now owned, and heretofore resident in this State, who have absented themselves, or been clandestinely carried away, or who may be employed abroad as Seamen, and have not returned or been brought back to their Owners, Masters or Mistresses, before the passing of this Act may within five Years be registered as effectually, as is ordered by this Act concerning those who are now within the State, on producing such Slave, before any two Justices of the Peace, and satisfying the said Justices by due Proof, of the former Residence, absconding, taking away, or Absence of such Slave as aforesaid; who thereupon shall direct and order the said Slave to be entered on the Record as aforesaid.

And Whereas Attempts may be made to evade this Act, by introducing into this State, Negroes and Mulattos, bound by Covenant to serve for long and unreasonable Terms of Years, if the same be not prevented.

Be it therefore enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That no Covenant of personal Servitude or Apprenticeship whatsoever shall be valid or binding on a Negroe or Mulatto for a longer Time than Seven Years; unless such Servant or Apprentice were at the Commencement of such Servitude or Apprenticeship under the Age of Twenty one Years; in which Case such Negroe or Mulatto may be holden as a Servant or Apprentice respectively, according to the Covenant, as the Case shall be, until he or she shall attain the Age of twenty eight Years but no longer.

And be it further enacted by the Authority aforesaid, That an Act of Assembly of the Province of Pennsylvania passed in the Year one thousand seven hundred and five, intitled “An Act for the Trial of Negroes;” and another Act of Assembly of the said Province passed in the Year one thousand seven hundred and twenty five intitled “An Act for “the better regulating of Negroes in this Province;” and another Act of Assembly of the said Province passed in the Year one thousand seven hundred and sixty one intitled “An Act for laying a Duty on Negroe and Mulatto Slaves imported into this Province” and also another Act of Assembly of the said Province, passed in the Year one thousand seven hundred and seventy three, intitled “An Act for making perpetual An Act for laying a duty on Negroe and Mulatto “Slaves imported into this Province and for laying an additional “Duty on said Slaves;” shall be and are hereby repealed annulled and made void.

John Bayard, Speaker

Enacted into a Law at Philadelphia on Wednesday the first day of March, Anno Domini One thousand seven hundred Eighty

Thomas Paine, Clerk of the General Assembly

Other states then followed Pennsylvania’s lead, expanding upon it by enacting less conservative measures. During a series of judicial reviews which were conducted in Massachusetts between 1781 and 1783, for example, state leaders there declared that slavery was incompatible with their state’s new constitution.

These various laws, while not perfect, did gradually achieve their aim of reducing slavery in northern states, as did 1807 legislation by the U.S. Congress which made it a crime for Americans to engage in international slave trade (effective January 1, 1808), and which ultimately reduced shipments of slaves from Africa to the United States by ninety percent. With respect to Pennsylvania, specifically, “the number of slaves dropped from 3,737 to 1,706” between 1790 and 1800, according to PHMC historians, “and by 1810 to 795. In 1840, there still were 64 slaves in the state, but by 1850 there were none.”

Meanwhile, Quakers and others active in abolition movements in Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia achieved some success by pressuring slaveholders to agree to free slaves via wills and other methods of manumission so that, by 1860, more than ninety percent of black men, women, and children in Delaware and nearly fifty percent in Maryland were free.

Despite these efforts, however, the ugliness of slavery continued to persist — a fact made all too clear in newspapers and other publications of the period, including via William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator. But it was, perhaps, the nation’s fugitive slave laws which finally made plain slavery’s seemingly unshakeable grip on the country. Passed by the U.S. Congress, the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 required that all escaped slaves, regardless of where they were captured, be returned to their masters — even if those escaped slaves had made it to safety via the Underground Railroad or other methods and had been given sanctuary by abolitionists in states where slaves had been permanently freed. In response, two years later, Harriet Beecher Stowe released her landmark, anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

After the U.S. Congress set the stage to reverse decades of anti-slavery progress with its passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act in 1854, abolitionists and other opponents of slavery banded together to form the Republican Party, which held its first national convention in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on February 22, 1856. Initially proposing a system which would contain slavery until each individual state where the practice still existed could be forced to eradicate it, the Republican Party adopted a harder, anti-slavery line in 1860 after the election of Abraham Lincoln as president of the United States.

Following the secession of multiple states from the Union, beginning with South Carolina on December 20, 1860, and the subsequent fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate States Army troops in mid-April 1861, the United States descended into a state of civil war with its federal government issuing a call for regular and volunteer troops to preserve the Union. On September 22, 1862, President Lincoln formally added the abolition of slavery as one of the federal government’s stated war goals with his release of the preliminary version of his Emancipation Proclamation, which decared that, effective January 1, 1863, “all persons held as slaves within any State, or designated part of a State, the people whereof shall then be in rebellion against the United States shall be then, thenceforward, and forever free.”

But it would take more than two years for that hoped-for dream to truly begin and nearly 150 years for it to be completely embraced by a divided nation.

THE 13TH AMENDMENT TO THE U.S. CONSTITUTION (THE ABOLITION OF SLAVERY)

“Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

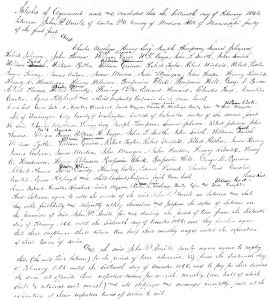

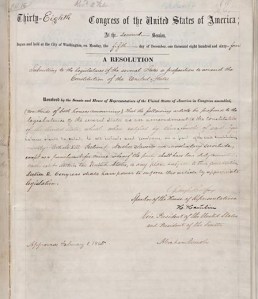

On January 31, 1865, the United States Congress approved the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, abolishing slavery in America. President Abraham Lincoln added his signature on February 1, 1865. (U.S. National Archives, public domain).

1864:

April 8, 1864: The United States Senate passes the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution by a vote of 38 to 6.

1865:

January 31, 1865: The U.S. House passes the 13th Amendment by a vote of 119 to 56.

February 1, 1865: President Abraham Lincoln approves the Joint Resolution of Congress. According to historians at The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, even though the U.S. Constitution does not require presidential signatures on amendments, Lincoln chooses to add his signature, making the 13th Amendment “the only constitutional amendment to be later ratified that was signed by a president.” The resolution is also ratified on this day by the Illinois Legislature, making Illinois the first state to ratify the amendment. (According to news reports, the Illinois Legislature actually ratified the amendment in Springfield, Illinois before Lincoln added his signature to the document in Washington, D.C.)

February 2, 1865: Rhode Island becomes the second state to ratify the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Michigan’s legislature also ratifies the amendment on this day.

February 3, 1865: Maryland, New York, and West Virginia ratify the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

February 6, 1865: Missouri ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

February 7, 1865: Maine, Kansas, and Massachusetts ratify the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

February 8, 1865: Pennsylvania ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution while Delaware initially rejects ratification of the amendment. (Delaware’s legislature will later approve it in 1901. See below for details.)

February 9, 1865: Virginia ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

February 10, 1865: Ohio ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

February 15–16, 1865: Louisiana ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution on February 15 or 16 while Indiana and Nevada both ratify the amendment on February 16, 1865.

February 23, 1865: Minnesota ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

February 24, 1865: Wisconsin ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution while Kentucky rejects ratification. (Kentucky’s legislature will later approve ratification in 1976. See below for details.)

March 9, 1865: Vermont’s governor approves the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

March 16, 1865: New Jersey initially rejects ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. (The state’s legislature will later approve it in 1866. See below for details.)

April 7, 1865: Tennessee ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

April 14, 1865: Arkansas ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

May 4, 1865: Connecticut ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

June 30, 1865: New Hampshire ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

November 13, 1865: South Carolina ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

December 2, 1865: Alabama’s provisional governor approves the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution while Mississippi rejects ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. (Mississippi’s certified ratification of the amendment will not be achieved until 148 years later. See below for detail.)

December 4, 1865: North Carolina ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

December 6, 1865: The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution is officially ratified when Georgia becomes the 27th state to approve the amendment. (America has a total of 36 states at this time in its history.) With this day’s formal abolition of slavery, four million Americans are permanently freed.

December 11, 1865: Oregon ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

December 15, 1865: California ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

December 18, 1865: United States Secretary of State William H. Seward certifies that the 13th Amendment has become a valid part of the U.S. Constitution.

William H. Seward, Secretary of State of the United States,

To all to whom these presents may come, greeting:

Dec. 18, 1865, Preamble: Know ye, that whereas the congress of the United States on the 1st of February last passed a resolution which is in the words following, namely:

“A resolution submitting to the legislatures of the several states a proposition to amend the Constitution of the United States.”

“Resolved by the Senate and House of the United States of America in Congress assembled, (two thirds of both houses occurring,) That the following article be proposed to the legislatures of the several states as an amendment to the Constitution of the United States, which, when ratified by three fourths of said legislatures, shall be valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the said constitution, namely:

“ARTICLE XIII.

“Section 1. Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.

“Section 2. Congress shall have power to enforce this article by appropriate legislation.”

And whereas it appears from official documents on file in this department that the amendment to the Constitution of the United States proposed, as aforesaid, has been ratified by the legislatures of the State of Illinois, Rhode Island, Michigan, Maryland, New York, West Virginia, Maine, Kansas, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Virginia, Ohio, Missouri, Nevada, Indiana, Louisiana, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Vermont, Tennessee, Arkansas, Connecticut, New Hampshire, South Carolina, Alabama, North Carolina, and Georgia; in all twenty-seven states;

And whereas the whole number of states in the United States is thirty-six; and whereas the before specially-named states, whose legislatures have ratified the said proposed amendment, constitute three fourths of the whole number of states in the United States;

Now, therefore, be it known, that I, WILLIAM H. SEWARD, Secretary of State of the United States, by virtue and in pursuance of the second section of the act of congress, approved the twentieth of April, eighteen hundred and eighteen, entitled “An act to provide for the publication of the laws of the United States and for other purposes,” do hereby certify that the amendment aforesaid has become valid, to all intents and purposes, as a part of the Constitution of the United States.

In testimony whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the Department of State to be affixed.

Done at the city of Washington, this eighteenth day of December, in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-five, and of the Independence of the United States of America the ninetieth.

WILLIAM H. SEWARD.

Secretary of State.

December 28, 1865: Florida ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

1866:

January 15, 1866: Iowa becomes the 31st state to approve the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (alternate date January 17, 1866).

January 23, 1866: New Jersey ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

1868:

June 9, 1868: Florida reaffirms its ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution as part of its legislature’s approval of a new state constitution.

1870:

February 17, 1870: Texas ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

1901:

February 12, 1901: Delaware ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

1976:

March 18, 1976: Kentucky ratifies the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

2013:

February 7, 2013: Mississippi becomes the final state to achieve certified ratification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

* Note: According to 2013 news reports by staff at ABC and CBS News, although Mississippi legislators finally voted for ratification of the 13th Amendment in 1995, they never notified the U.S. Archivist. As a result, their effort to formally abolish slavery was still not official – an error which was discovered in 2012 by Ranjan Batra, an immigrant from India and professor of Neurobiology and Anatomical sciences at the University of Mississippi Medical Center. After enlisting the help of a medical center colleague (long-time Mississippi resident Ken Sullivan) in uncovering documentation of the oversight, Batra then alerted Mississippi’s Secretary of State Delbert Hosemann, who finally rectified the error by sending the U.S. Office of the Federal Register a copy of Mississippi’s 1995 resolution on January 30, 2013. When that resolution was published in the Federal Register on February 7, 2013, Mississippi’s abolition of slavery finally became official.

Sources:

- “An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery — March 1, 1780.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, retrieved online January 31, 2019.

- “13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution: Abolition of Slavery,” in “America’s Historical Documents.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, retrieved online January 31, 2019.

- Condon, Stephanie. “After 148 Years, Mississippi Finally Ratifies 13th Amendment Which Banned Slavery.” New York, New York: CBS News, February 18, 2013.

- Foner, Eric. Free Soil, Free Labor, Free Men: The Idealogy of the Republican Party Before the Civil War. Cary, North Carolina: Oxford University Press, April 1995.

- “Founding of Pennsylvania Abolition Society,” in “Africans in America.” Boston, Massachusetts: WGBH (PBS), retrieved online January 31, 2019.

- Head, David. “Slave Smuggling by Foreign Privateers: The Illegal Slave Trade and the Geopolitics of the Early Republic“, in Journal of the Early Republic, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 433-462. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: University of Pennsylvania Press, Fall 2013.

- Kolchin, Peter. American Slavery, 1619–1877, pp. 78, 81–82. New York, New York: Hill and Wang (Macmillan), 1994.

- “Massachusetts Constitution and the Abolition of Slavery,” in “Massachusetts Court System.” Boston, Massachusetts: Commonwealth of Massachusetts, Mass.gov, retrieved online January 31, 2019.

- McClelland, Edward. “Illinois: First State to Ratify 13th Amendment.” Chicago, Illinois: NBC 5-Chicago, November 16, 2012.

- “No. 5: William H. Seward, Secretary of State of the United States” (certification of the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution), in “A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774–1875: Statutes at Large,” in “American Memory.” Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, retrieved online January 31, 2019.

- Oakes, James. Freedom National: The Destruction of Slavery in the United States, 1861–1865. New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2013.

- “Ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment, 1866: A Spotlight on a Primary Source by Iowa General Assembly,” in “History Now.” New York, New York: The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, retrieved online January 31, 2019.

- U.S. Senate Document No. 112-9 (2013), 112th Congress, 2nd Session: “The Constitution of the United States Of America Analysis And Interpretation Centennial Edition Interim Edition: Analysis Of Cases Decided By The Supreme Court Of The United States To June 26, 2013s,” p. 30 (of large PDF file). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, retrieved online January 31, 2019.

- Waldron, Ben. “Mississippi Officially Abolishes Slavery, Ratifies 13th Amendment.” New York, New York: ABC News, February 18, 2013.

You must be logged in to post a comment.