Frank, James, and William Sieger were among the many blood brothers who also became brothers-in-arms when they enlisted for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry during the American Civil War.

All three would ultimately survive the war—but they would each serve in different companies of the regiment—and their individual life journeys would diverge dramatically, post-war, within a few short years of their having returned home to the Great Keystone State.

Formative Years

Born in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, on 30 April 1838, 11 October 1843, and 19 January 1845, respectively, Franklin, James, and William H. Sieger were sons of Joseph P. Sieger (1811-1869), a native of Siegersville, Lehigh County (now Orefield, Lehigh County), and Naomi Amilia (Kern) Sieger (1818-1887), who was also a Lehigh County native.

Their siblings were Caroline Sieger (1841-1917), who was born on 13 March 1847; Madison Sieger (1847-1919), who was born in April 1847 and known to family and friends as “Matt”; Elias Sieger (1849-1919), who was born on 13 February 1849 and known to family and friends as “Eli”; Elizabeth A. Sieger (1851-1918), who was born in Siegersville on 9 August 1851 and known to family and friends as “Lizzie”; and Oliver Peter Sieger (1854-1926), who was born in Siegersville on 1 December 1854.

In 1850, Frank, James and William Sieger lived in North Whitehall Township, Lehigh County with their parents and siblings Caroline, Matt and Eli. Their father was described as a “Tinker” by that year’s federal census enumerator, as was William George, who also resided with the Sieger family at this time. That designation was meant to indicate that both men were tinsmiths.

By 1860, the Sieger household included Frank and William Sieger, their parents, and siblings Caroline, Madison, Elizabeth, and Oliver—but not James, according to the federal census enumerator who arrived at the Sieger family home in late July 1860. Researchers have not yet determined whether or not this was an oversight by that year’s census taker, or if James was residing elsewhere (because he may have been apprenticed to a tradesman outside of the Sieger family), but what is clear from that year’s census is that the Sieger family home was located in the community of Orefield in North Whitehall Township, Lehigh County, that the family’s patriarch, tinsmith Joseph Sieger, had amassed real and personal estate holdings valued at $2,845 (roughly $99,100 in 2022 dollars), and that William, Caroline, Madison, and Elizabeth were all attending school while Frank was working beside their father as a tinsmith—signaling that tinsmithing was most likely the family’s profession. In addition, the census taker also noted that a fifty-five-year-old physician—William Kohler—was living with the Siegers at this time.

“The Union Is Dissolved” (broadside announcing South Carolina’s secession from the United States, Charleston Mercury, 20 December 1860, U.S. Library of Congress and National Museum of American History, public domain).

As the year wore on, the Siegers, like many families across Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, were becoming increasingly aware that their nation was growing more and more divided with each passing day, as state leaders across America’s Deep South pushed the United States closer and closer to disunion.

The dominos began to fall when South Carolina seceded from the Union on 20 December 1860, followed by Mississippi (9 January 1861), Florida (10 January 1861), Alabama (11 January 1861), Georgia (19 January 1861), Louisiana (26 January 1861), and Texas (1 February 1861).

By mid-April 1861, civic leaders across Pennsylvania were hosting region-wide meetings, bringing together Pennsylvanians from diverse economic backgrounds, political affiliations and religious traditions to educate them on the most pressing issues of their day, galvanize them to eradicate the brutal practice of chattel slavery across America and preserve the nation’s Union.

According to Alfred Mathews and Austin N. Hungerford, authors of History of the Counties of Lehigh and Carbon, in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, during one such meeting—on 13 April 1861—Captain Tilghman H. Good, the commanding officer of the famed local militia unit known as the Allen Rifles, was appointed to lead a newly formed group of volunteers who could try to make the latter two of those objectives a reality:

[On] April 13, 1861, two days previous to the call of President Lincoln for troops, the citizens of Lehigh and Northampton Counties called a public meeting at Easton, ‘to consider the posture of affairs and to take measures for the support of the National Government.’ At this meeting the first Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers was formed. The captain of the ‘Allen Rifles’ (Col. T.H. Good) was chosen lieutenant-colonel of the regiment, in conjunction with Capt. Samuel Yohe, of Easton, as colonel, and Thomas W. Lynn as major. The ‘Allen Rifles,’ having by this transaction lost their captain, quickly proceeded to form themselves into a new company, retaining, however, the name ‘Allen Rifles,” and on the 18th of April, 1861, left for Harrisburg, and were there mustered into the service on April 20, 1861, as Company I, First Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, being in all eighty-one men and officers.

Civil War Military Service

On 22 October 1862, William H. Sieger became the first of three Sieger brothers to enlist for Civil War military service. Just seventeen at the time, he evidently lied about his age to evade the U.S. Army’s requirement that candidates for enrollment be at least eighteen; military records show that William stated that he was a nineteen-year-old tinsmith residing in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania when he enrolled at Allentown.

William’s older brother, James M. Sieger, then followed him into the service five days later—on 27 October 1862—by also enrolling in Lehigh County.

Both brothers then mustered in at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg on 29 October—with the same regiment—but in different units. William H. Sieger mustered in as a Private with Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry while James M. Sieger mustered in as a Private with the 47th Pennsylvania’s K Company, which had been formed with the intent of being “an all-German company,” according to news reports at the time the company was established in 1861. According to his military records, James Sieger was a nineteen-year-old laborer residing in Allentown who officially joined the regiment from a recruiting depot on 19 November 1862.

Both young men were joining a combat-hardened regiment that had been bloodied badly just days before in the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Companies G and K (the units William and James Sieger were joining) had been hit particularly hard during that engagement, losing both of their commanders, as well as multiple other officers and enlisted men on 22 October 1862.

That fact may explain why the underaged William H. Sieger was transferred from the 47th Pennsylvania’s G Company to its Regimental Band in January of 1863. (The regiment needed adult soldiers who could withstand the rigors of combat at this juncture, rather than teenaged boys who had lied about their age in order be thought eligible for enlistment.) Or, it may simply have been, as regimental historian Lewis Schmidt theorized, that “Privates Frederick Jacobs, William Seiger [sic], and James Gaumer of Company G were transferred” because “the 47th was assembling a new group of musicians to replace Pomp’s Coronet Band which had been discharged the previous September.”

Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry spent 1863 and the opening weeks of 1864 garrisoning federal installations in Florida as part of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps, Department of the South. The men of the Regimental Band and Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I were assigned to duty at Key West’s Fort Taylor while the soldiers from Companies D, F, H, and K garrisoned Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the coast of Florida with members of both groups periodically moved between the forts as regimental responsibilities were refined by the Union Army’s more senior brigade officers.

The climate was harsh and unpleasant and disease was a constant companion and foe.

But life was not entirely bleak. In a letter to the Sunbury American on 23 August 1863, Henry Wharton, one of the 47th Pennsylvanians stationed at Fort Taylor, described Thanksgiving celebrations held by the regiment and residents of Key West and a yacht race the following Saturday at which participants had “an opportunity of tripping the ‘light, fantastic toe,’ to the fine music of the 47th Band, led by that excellent musician, Prof. Bush.”

The time spent in Florida was also notable for the men’s commitment to preserving the Union. Many of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who could have returned home, having well and honorably completed their service, chose instead to re-enlist.

1864

Fort Jefferson’s moat and wall, circa 1934, Dry Tortugas, Florida (C.E. Peterson, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to expand the Union’s reach further by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858 following the United States’ third war with the Seminole Indians. Per orders issued earlier in 1864 by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, that the fort be used to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade, Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of men from Company A were charged with movig north to expand the fort and conduct raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence while the remainder of the 47th Pennsylvania continued to guard Forts Taylor and Jefferson. Graeffe and his men subsequently turned Fort Myers into both their base of operations and a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate Army deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops. According to Schmidt:

Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard….

A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documents the time of Richard Graeffe and the men under his Florida command this way:

A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (which was situated across the river from New Orleans and is now a neighborhood in New Orleans), followed on 1 March by the other 47th Pennsylvanians from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reunited regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.)

Red River Campaign

The early days on the ground in Louisiana quickly woke the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers up to just how grueling this new phase of duty would be. From 14-26 March, most members of the regiment marched for the top of the “L” in the L-shaped state, by way of New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington.

Their primary destinations, during this first on-ground phase of the campaign, were Alexandria and Natchitoches, Louisiana.

While in Natchitoches, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James and John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania from 4-5 April 1864. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were then officially mustered in for duty on 22 June at Morganza. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “(Colored) Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long hard trek through enemy territory, the men encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill (now the Village of Pleasant Hill) the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day.

Having marched from morning until mid-afternoon on 8 April, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were quickly ordered to engage the enemy (ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division) as the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads began. Also known as the Battle of Mansfield because of its proximity to the community of Mansfield), it would prove to be a devastating engagement for the 47th. As the rifle and cannon fire intensified on both sides during the afternoon, sixty members of the regiment—the equivalent of more than half of one company—were cut down.

The fighting waned only when darkness fell. Exhausted, those who were uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner and son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

Casualties were once again severe with multiple men killed or wounded. Among the wounded were Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, the regiment’s second-in-command, and the regiment’s two color-bearers, both from Company C, who were shot while preventing the American flag from falling into enemy hands.

Still others from the 47th were captured, marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas (the largest of the Confederate prisons west of the Mississippi), and held there as prisoners of war until released during prisoner exchanges between July and November 1864. At least two of those imprisoned 47th Pennsylvanians would never make it out of that prison alive while Private Joseph Clewell would later succumb to disease-related complications—on 18 June 1864—while being held as a POW at the Confederate Army’s hospital at Shreveport, Louisiana. (Clewell had initially been part of the 47th Pennsylvania’s roster of Unassigned Men upon muster in on 4 November 1863.)

Following what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, the 47th Pennsylvanians fell back to Grand Ecore, where they remained for eleven days and engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers then moved back to Natchitoches Parish. Starting out on 22 April, they arrived in Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night after marching forty-five miles. While en route, they were attacked again—this time at the rear of their brigade, but they were able to quickly end the encounter and move forward.

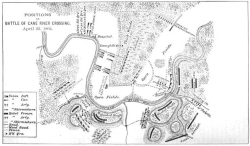

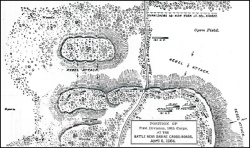

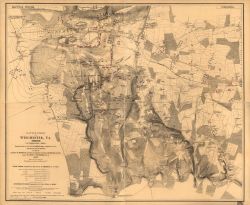

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April 1864), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee’s Confederate Cavalry in the Battle of Monett’s Ferry (also known as the “Cane River Crossing”). Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s 20-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops situated near a bayou and on a bluff, Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending two other brigades to find a safe spot where his Union troops could ford the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvanians supported Emory’s artillery.

Emory’s troops subsequently worked their way across the Cane River, attacked Bee’s flank, forced a Rebel retreat, and then erected a series of pontoon bridges to enable the 47th and other remaining Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners.

In a letter penned from Morganza, Louisiana on 29 May, Henry Wharton described what had happened to the 47th Pennsylvanians during and immediately after making camp at Grand Ecore:

Our sojourn at Grand Ecore was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one on the boys, for by ten o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty-five miles. On that day the rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns, opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebel prisoners say it ‘seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth of this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton of Western Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” for the Union officer who ordered its construction, Lt.-Col. Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, the 47th Pennsylvanians learned they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. The same day of their arrival, Private Henry T. Dennis was promoted to the rank of Corporal, and Corporal Martin H. Hackman became Sergeant Hackman. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were then assigned, again, to the hard labor of fortification work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that would enable Union gunboats to more easily make their way back down the Red River. According to Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river. After a great deal labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits [sic] on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Marching onward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed for Avoyelles Parish. Wharton noted in his letter that:

On Sunday, May 15, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad wherewith the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired and we advanced ‘till dark, when the forces halted for the night, with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

Having entered far enough into Avoyelles Parish, they “rested on their arms” for the night, half-dozing without pitching their tents, but with their rifles right beside them. They were now positioned just outside of Marksville, Louisiana on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, the infantry advanced in line until they reached Mousoula [sic], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic] on the Achafalaya [sic] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of our army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.*

* Note: Disease continued to be a truly formidable foe, claiming still more members of the 47th Pennsylvania. Privates Henry Smith, Christian Schlu (alternate spelling: Schlea) and Alpheus Dech (alternate spellings: Alfred Dech or Deck) would succumb to disease-related complications, respectively, on 30 May, and 2 and 3 June at the Union’s Marine Hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana, followed by Private Jonathan Heller, who would die at the Charity General Hospital in New Orleans on 7 June.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Continuing on, the surviving members of the 47th marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. According to Wharton, the members of Company C were subsequently sent on a special mission which took them on an intense one hundred and twenty mile journey:

Company C, on last Saturday was detailed by the General in command of the Division to take one hundred and eighty-seven prisoners (rebs) to New Orleans. This they done [sic] satisfactorily and returned yesterday to their regiment, ready for duty. While in the City some of the boys made Captain Gobin quite a handsome present, to show their appreciation of him as an officer gentleman.

While encamped at Morganza, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania in Beaufort, South Carolina (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864.

The regiment then moved on once again, finally arriving in New Orleans in late June. On the Fourth of July, the Sieger brothers and their 47th Pennsylvania comrades learned that their fight was not yet over as they received new orders to return to the East Coast for further duty.

As they did during their tour through the Carolinas and Florida, the men of the 47th had battled the elements and disease, as well as the Confederate Army, in order to survive and continue to defend their nation. But the Red River Campaign’s most senior leader, Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks, would not. Removed from command amid the controversy regarding the Union Army’s perceived subpar performance during this campaign, he was placed on leave by President Abraham Lincoln. Banks later redeemed himself by spending much of his time in Washington, D.C. as a Reconstruction advocate for the people of Louisiana.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

After receiving orders on the 4th of July to return to the East Coast, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Louisiana in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I steamed for the Washington, D.C. area beginning 7 July while the men from Companies B, G and K remained behind on detached duty and to await transportation. Led by F Company Captain Henry S. Harte, the latter group finally sailed away at the end of the month, arrived in Virginia on 28 July, and reconnected with the bulk of the regiment at Monocacy, Virginia on 2 August.

Due to the timing of their arrival, the men from Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I likely did not engage in the battle that was taking place at Fort Stevens, but many of those men did have a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln before participating in the fighting at Snicker’s Gap, Virginia.

“Berryville from the West. Blue Ridge on the Horizon,” Berryville Pike, Virginia, 1 August 1884 (photo: T. D. Biscoe, courtesy of Southern Methodist University).

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was subsequently assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, Virginia during the opening days of that month, and then engaged in a series of back-and-forth movements over the next several weeks between Halltown, Berryville and other locations within the vicinity (Middletown, Charlestown and Winchester) as part of a “mimic war” being waged by the Union forces of Major-General Philip H. Sheridan (“Little Phil”) against those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early (“Ol’ Jube”).

Meanwhile, back home in Pennsylvania, William and James Sieger’s older brother, Frank Sieger, was reporting for Civil War military duty. Following his enrollment at the Union Army’s recruiting depot in Norristown, Pennsylvania on 23 August 1864, Frank Sieger officially mustered in that same day as a Private with the same regiment in which his brothers had been serving. Like his brothers, he was enrolled in a different company, perhaps thinking that, if all three of the brothers were to survive the war, they might have a better chance of doing so if they were not serving side-by-side in the same unit of the same regiment. Military records at the time of enrollment described Frank Sieger as a “Recruit” who was a twenty-five-year-old tinsmith residing in North Whitehall, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, who was 5’8” tall with brown hair, brown eyes and a light complexion.

The September Battles of the Shenandoah Valley

The next engagement with Confederate troops for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers was in the Battle of Berryville, Virginia from 3-4 September 1864. Shortly thereafter, multiple officers and enlisted members of the regiment were honorably discharged through 18 September 1864 upon expiration of their respective, initial terms of service.

Those members of the regiment who remained—liked William, James and Frank Sieger—were about to engage in the 47th Pennsylvania’s greatest moments of individual and collective valor.

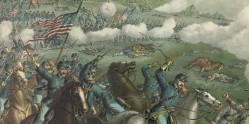

Together with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the U.S. Army’s 19th Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on the Confederate forces of Lieutenant-General Early in the Battle of Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”). The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. After finally reaching the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with the Confederate Army commanded by Early. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and the 19th Corps were directed by Brigadier-General Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as another Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops trying to cross a clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice—once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

The 19th Corps, with the 47th in the thick of the fighting, then began pushing the Confederates back. Early’s “grays” retreated in the face of the valor displayed by Sheridan’s “blue jackets.” Leaving 2,500 wounded behind, the Rebels retreated to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September), eight miles south of Winchester, and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union men which outnumbered Early’s three to one.

Afterward, the wounded were gathered up and moved to the regimental hospital while the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who were still standing were sent out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek.

Among the 47th Pennsylvanians listed on the casualty rosters was Private James M. Sieger of Company K. According to the special veterans’ census that would later be taken in 1890, he had sustained a wound above one of his knees during the Battle of Fisher’s Hill.

Battle of Cedar Creek, 19 October 1864

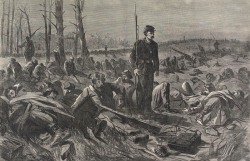

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle pits, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

During that fall of 1864, Major-General Philip Sheridan also began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving Confederate troops into submission by destroying Virginia’s crops and farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents—civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. His men were then able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles—all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he rode rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The Union’s counterattack so pummeled Early’s forces that the men of the 47th were later commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

During the day’s intense fighting, Regimental Chaplain William Rodrock suffered a frightening near miss as a bullet pierced his cap. A significant number of men from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were far less fortunate, however; the casualty rate sustained by the 47th at Cedar Creek was so high, in fact, that when the final numbers were tallied, regimental leaders realized that the regiment had lost the equivalent of nearly two full companies of men.

Sergeant William Pyers, the C Company man who had so gallantly rescued the flag at Pleasant Hill, was cut down and later buried on the battlefield. Brevet-Major John Goebel, who had suffered a grievous gunshot wound, died three weeks later, on 5 November 1864, of wound-related complications while receiving care at the Union Army’s post hospital at Winchester, Virginia.

Still others reportedly succumbed to starvation, disease or physical abuse after being captured and transported from the Cedar Creek battlefield area to the Confederate Army’s notorious Salisbury, North Carolina prison camp.

Within weeks of the battle’s end, the surviving 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered to Camp Russell near Winchester, where they remained from November through most of December. Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were then ordered to take up outpost and railroad guard duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia. Five days before Christmas, they marched through a driving snowstorm to reach their new home.

1865—1866

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, at the side of the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag half-mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Assigned first to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah in February 1865, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry moved back to Washington, D.C., via Winchester and Kernstown. By 19 April 1865, they were responsible for helping to defend the nation’s capital in the wake of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Encamped near Fort Stevens, they were resupplied and received new uniforms.

Letters home and later newspaper interviews with survivors of the 47th Pennsylvania indicate that at least one 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while others may have guarded the Lincoln assassination conspirators during the early days of their imprisonment.

Attached to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania also participated in the Union’s Grand Review of the Armies on 23-24 May.

Just over a week later, Frank Sieger became the first of the Sieger brothers to depart from military life when he was honorably discharged from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on 1 June 1865, under the requirements of General Order No. 53 of the U.S. Army’s Middle Military Division, which was issued on 30 May 1865. He then returned to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley.

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

On their final southern tour, the remaining Sieger brothers and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed in Savannah, Georgia from 31 May to 4 June. Assigned again to Dwight’s Division, this time they were attached to the 3rd Brigade, U.S. Department of the South. Relieving the 165th New York Volunteers in July, they next quartered at the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury in Charleston, South Carolina.

Duties during this time were largely Provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related, including the repair of railroads and other key infrastructure items which had been damaged or destroyed during the long war. Personnel changes also continued to be made to the regiment.

Finally, on Christmas Day of that year, the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantrymen began to honorably muster out for the last time at Charleston, a process which continued through early January. Musician William Sieger of the Regimental Band and Private James M. Sieger of Company K were among those who mustered out on 28 December.

Following a stormy voyage home, the 47th Pennsylvanians disembarked in New York City. The weary men were then shipped to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader on 9 January 1866, the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were officially given their final discharge papers.

Like their older brother before them, William and James Sieger then also returned home to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley.

Return to Civilian Life

Less than three years after the end of the Civil War, a major incident occurred that forever altered the lives of Frank, James and William Sieger. Their father, Joseph P. Sieger, died at the age of fifty-seven in Lehigh County on 13 April 1869. A master tinsmith who had encouraged William’s brother, Frank, to learn the art of tinsmithing, Joseph Sieger presumably would have encouraged his other sons to join him in his work had he lived another decade or two. Instead, he was laid to rest at the Jordan Lutheran Cemetery in Orefield, Lehigh County, and the Sieger brothers were left to make their way during a rapidly changing America that would be transformed by the Reconstruction and Second Industrial Revolution eras.

The Post-Civil War Life of William H. Sieger

The post-Civil War life story of the youngest of the Sieger brothers, William H. Sieger, is presented here first because it is the shortest and, ultimately, the saddest.

Following his return from the war, William Sieger chose not to go into the family business of tinsmithing but, instead, appears to have pursued a career in the hospitality industry. By 1870, he was reportedly living at a hotel operated by Levi Hottenstein in Allentown, Lehigh County. According to that year’s federal census, William was employed by Hottenstein as a “Hotel Keeper.” Also living with him at this time was his sister, Lizzie.

Note: The Hottensteins’ hotel was evidently a sizeable hotel by the day’s standards and also a family operation that employed the Hottensteins’ sons Jacob and Charles as, respectively, a laborer and hotel clerk. According to the 1860 federal census, Levi Hottenstein’s real and personal property were valued at $41,200 (roughly $910,000 in 2022 dollars). He also employed five domestic servants (Jane Shoemaker, Ellie Keider, Kate Bear, Anna Tolan, and Amelia Fisher), and rented rooms to twenty-six guests, including attorneys, barbers, a brickmaker, carpenters, a clothing maker, a harnessmaker, a shoemaker, and store clerks. Several of those guests were described by the census taker as natives of Saxony and Württemberg.

Important Point: Although the 1870 federal census enumerator indicated that neither William Sieger, nor his sister Lizzie, could read or write, it is likely that what that census taker was actually documenting was that they were two of the many residents of Lehigh County who were of German heritage who still primarily spoke and wrote in German or its variant—Pennsylvania Dutch. (Hoteliers Levi Hottenstein and his wife, Maria, were also described as being unable to read or write, and were also likely German or Pennsylvania Dutch speakers.)

Researchers have learned that the hotel where William Sieger lived and worked was, in fact, Allentown’s Eagle Hotel—and that Hottenstein was operating the hotel in partnership with William H. Sieger, according to Levi Hottenstein’s obituary in the 16 February 1907 edition of The Allentown Leader, which noted that:

Levi S. Hottenstein, one of the oldest and most prominent residents of Allentown, died at 4:30 this morning [16 February 1907] at his home, 1127 Hamilton street, in his 87th year….

Deceased was born on the homestead at Maxatawny, Berks County, Nov. 25, 1820, and was a son of the late Mr. and Mrs. Jacob Hottenstein…. His mother was born a Swoyer. His father, who lived to be 92 years old, was the son of an original German settler. Mr. Hottenstein was educated in the public schools of his native home and for a number of years worked on his family’s farm. When he was a young man his father purchased a farm adjoining the homestead, which he conducted 22 years.

Feb. 28, 1868, he sold the farm and came to Allentown with his family. In partnership with Wm. H. Sieger he conducted the Eagle Hotel on Center Square…. Mr. Sieger died three years later….

But, in truth, the end for William H. Sieger was far more shocking, and heartbreaking, than Hottenstein’s obituary reported.

Death and Interment

According to the 4 February 1874 edition of the Tunkhannock Republican, “William Sieger, a hotel keeper at Allentown, aged about 30, hung himself in his stable on Friday morning.”

That terrible day was 30 January 1874—eleven days after William’s twenty-ninth birthday. He was subsequently laid to rest at the Jordan Lutheran Cemetery in Orefield, Lehigh County.

William H. Sieger’s mother and siblings transfer executorship of his will to John Butz, 3 February 1874 (Register of Wills, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, public domain).

Legal activities regarding William H. Sieger’s final will and testament began shortly thereafter—a predictable outcome of his death—due more to his standing in the community as a partner in one of Allentown’s most respected businesses, rather than its tragic nature. Among the records contained in his probate file at Lehigh County’s Register of Wills office were lengthy lists of food, dry goods, business furnishings, and other items: canned tomatoes, chairs, dishes, dried apples, goblets, lamps, pillow cases, spoons, tablecloths, table knives, towels, whiskey, wine, and other supplies that William Sieger had purchased for use in operating the Eagle Hotel. Also included was a letter from William’s mother and brother, Frank, informing the Register of Wills that they were renouncing their claim to serve as executors in order to allow William’s brother-in-law, John D. Butz, to assume responsibility for the resolution of William’s estate. Accountants valued William Sieger’s hotel supply stock at roughly $75,170 (approximately $1,906,344 in 2022 dollars)—after having paid off various sums due to suppliers and others to whom William Sieger had owed money as part of his normal business operations.

John Butz was engaged in oversight of the resolution of William H. Sieger’s estate through 1881, according to those same probate records.

What Was the Possible Reason for William H. Sieger’s Death by Suicide?

Researchers do not yet have an answer to this question. From currently available evidence, it appears that William H. Sieger was doing well in his Eagle Hotel Partnership with Levi Hottenstein. And, unlike E Company Private Jacob Ochs, another 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer who ended his life by hanging himself a decade after William Sieger had done so, William Sieger did not appear to have been wounded in battle during the war. So, he was likely not struggling financially and had also apparently not developed any addictions from pain medications or alcoholic self-medication related to a battle wound (as Jacob Ochs had).

It is possible, though, that both of these veterans were hard-working, healthy men who simply had the terrible misfortune to develop war-related post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

We can make this educated guess about William Sieger’s life in mid-19th-century Pennsylvania because we now know, thanks to decades of recent mental health research, that PTSD is an illness that can strike anyone at any time and can severely affect normal human functioning for many years after its symptoms first begin. Those who suffer from PTSD may experience anxiety, depression, difficulty maintaining work or social relationships, drug and/or alcohol abuse, eating disorders, and/or suicidal tendencies because this illness’s symptoms—hypervigilance to, and avoidance of, anyone or anything that might cause flashbacks, hallucinations, nightmares, or other intrusive memories about the germinative incident; an exaggerated startle response and difficulty concentrating; dyspnea/shortness of breath; effort fatigue; feelings of guilt, hopelessness, or shame; emotional or physical numbing and a flat affect; irritability or anger; heart palpitations; sleep disturbance or insomnia; and sweating—take a terrible toll on the body, as well as the mind.

Known during the American Civil War as “Soldiers’ Heart,” PTSD was researched and written about in the late 1860s and early 1870s as an anxiety disorder linked to heart disease by Jacob Mendes da Costa, M.D., a graduate of Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College who became a physician at Turner’s Lane Hospital in Philadelphia during the Civil War.

Why William Sieger may have developed Soldiers’ Heart/PTSD when his brothers, friends and neighbors apparently did not is still an unsolved mystery, but this condition could very likely have developed due to a war that left deep emotional scars on many of its participants because of the ways in which it was waged—“concentrated and personal, featuring large-scale battles in which bullets … caused over 90 percent of the carnage,” according to the late journalist Tony Horwitz:

Most troops fought on foot, marching in tight formation and firing at relatively close range, as they had in Napoleonic times. But by the 1860s, they wielded newly accurate and deadly rifles, as well as improved cannons. As a result, units were often cut down en masse, showering survivors with the blood, brains and body parts of their comrades.

Many soldiers regarded the aftermath of battle as even more horrific, describing landscapes so body-strewn that one could cross them without touching the ground….

Wounded men who survived combat were subject to pre-modern medicine, including tens of thousands of amputations with unsterilized instruments….

Though geographically less distant from home than soldiers in foreign wars, most Civil War servicemen were farm boys, in their teens or early 20s, who had rarely if ever traveled far from family and familiar surrounds. Enlistments typically lasted three years….

These conditions contributed to what Civil War doctors called “nostalgia,” a centuries-old term for despair and homesickness so severe that soldiers became listless and emaciated and sometimes died. Military and medical officials recognized nostalgia as a serious “camp disease,” but generally blamed it on “feeble will,” “moral turpitude” and inactivity in camp. Few sufferers were discharged or granted furloughs, and the recommended treatment was drilling and shaming of “nostalgic” soldiers….

So, William Sieger may very well have been subject to “othering” by his fellow soldiers, veterans, members of his community, and/or family members—made to feel ashamed, guilty, or “less than” because he had not been wounded in combat as had his brother, James M. Sieger.

It is also quite possible that, if William Sieger had been required to assume the role(s) of “stretcher bearer,” or “grave digger,” or “medical assistant” who helped physicians perform amputations during the war—as many drummer boys and regimental band members had been required to do—he may have witnessed so much gore and death that his young mind was forever unable to rid itself of what his eyes and ears had seen and heard.

Regardless of the cause(s), William H. Sieger was evidently in so much emotional pain during the early 1870s that he felt that, despite his success in business, his life was no longer worth living.

The Post-War Life of James M. Sieger

Following his own honorable discharge from the military, William Sieger’s brother, James M. Sieger, also returned home to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, but his life would also diverge from that of his other siblings.

Sometime in or before the mid-1870s, James Sieger chose to pack his belongings and move to western Pennsylvania. There, in Pittsburgh, Allegheny County, on 18 August 1877, he and his wife, Margaret (Biggs) Sieger, welcomed the birth of their daughter, Florence Aquilla Sieger (1877-1954).

Researchers have not yet been able to learn much about the trio’s life together during this phase of their journey, but have been able to determine that, in 1887, James Sieger opted for an even more radical change of life—by relocating with his wife and daughter to Missouri.

In 1890, they resided in St. Joseph, Washington Township, Buchanan County, Missouri, according to the 1890 Special Census of Surviving Soldiers, Sailors, and Marines, and Widows of the Civil War. That census ledger also documented that James M. Sieger had been wounded above the knee during the Battle of Fisher’s Hill, Virginia (September 1864), and that multiple Union Army veterans were residents of the same town where he had settled. Less than two years later, he filed for, and was awarded, a U.S. Civil War Pension on 14 January 1892.

A member of the South Methodist Church in St. Joseph Missouri since roughly 1894, James Sieger’s daughter, Florence Aquilla Sieger, was married to George Loomis (1865-1950) on 22 December 1898. The next year, Florence and George relocated to a new home in Livingston County, Missouri, where they began their own family as they welcomed the births of daughter Florence, who would reportedly die in 1925; daughter Lillian Mae, who would grow up to marry Lloyd Raymond Gastineau (1902-1981) in 1896 and then raise a family with him in Chillicothe, Livingston County, Missouri; and Lester Loomis, who was reportedly a resident of Kansas City at the time of his sister Florence’s passing in the mid-1950s.

By 1910, widower James Sieger had become a boarder residing in Chula, Cream Ridge Township, Livingston County with salesman Robert White and his family.

Illness, Death and Interment

On 2 April 1917, James M. Sieger suffered an episode of apoplexy that ended his life eleven days later. Following his death on 13 April, he was laid to rest at the Plainview Cemetery (also known as the Chula Cemetery) in the Village of Chula Livingston County, Missouri on 14 April.

According to James Sieger’s obituary in the 2 May 1917 edition of The Allentown Leader:

James M. Sieger, a native of Siegersville, Lehigh County, died at his home at Chula, Missouri, in his seventy-fourth year. He was a son of the late Joseph and Amy (Kern) Sieger. During the Rebellion he served as a private in Co. K, Forty-seventh Regiment, Penna. Vols. In 1887, he went to Missouri after some years of residence in the western part of the state [Pennsylvania]. Mr. Sieger is survived by three children, all living in Missouri, and these brothers and sisters: Frank Sieger, Youngstown, Ohio; Mrs. Frank Wilson, Catasauqua; Matt. Sieger, Northampton; Elias Sieger, Coplay; Oliver, Kane, Pa.; and Mrs. Elizabeth Butz, Allentown.

Following her death in Chillicothe, Livingston County, Missouri on 31 May 1954, James Sieger’s daughter Florence Aquilla (Sieger) Loomis, was laid to rest at the Plainview Cemetery in Chula.

The Post-War Life of Franklin Sieger

During the late 1860s, Frank Sieger, the oldest brother of William and James Sieger, relocated to Mercer County, Pennsylvania, where he opened a tinsmith business and met, married and began his own family with Zidania Virginia Locke Homer (1845-1928), a daughter of David and Elizabeth B. (Miller) Homer. Their children were: Nora Elizabeth (1867-1942), who was born on 5 September 1867 and went on to marry and build a life with Gustave Edwin Sussdorff (1843-1903), M.D.—first on the East Coast and then in the San Francisco Bay Area of California; Emma, who was born circa 1869; Dot, who was born in May 1872; Daisey, who was born in August 1876 and went on to marry Michael Aloysius McGinnis (1882-1949); and David Homer Sieger (1879-1945; surname later spelled as “Saeger”), who was born in Greenville, Mercer County on 1 September 1879, who also later relocated to the San Francisco Bay Area of California.

Note: According to his obituary in the 7 April 1903 edition of The San Francisco Call, Gustave E. Sussdorff, M.D. was a native of North Carolina who became “one of the most widely known and highly respected physicians” in San Francisco, California. Per Kenneth Anderson, author of Strychnine & Gold (Part 1), Nora (Sieger) Sussdorff’s husband, Gustave, was associated with the Keeley Institute of Los Gatos, California, and operated his related medical practice in an office in San Francisco’s Academy of Science Building.

Together, Nora and Gustave Sussdorff, welcomed the arrival of their son, Homer Ignatius Sussdorff, who was born in San Francisco, California on 13 December 1895.

Homer Ignatius Sussdorff changes Surname to Van Horne, 1920 (University of California, public domain).

Widowed by her husband in 1903, Nora Elizabeth (Sieger) Sussdorff remarried sometime before 1916, according to the State of California’s voter registration records, which documented that she resided at 2542 Chilton Way in the city of Berkeley in Alameda County, California that year and that she was a Republican voter. According to the 1920 federal census, her second husband was hotel manager John H. Van Horne. That year, they resided in San Francisco with Nora’s son, Homer, a medical student at the University of California, San Francisco who had adopted the surname of his stepfather, according to that year’s census, which was then shown as “Vanhorne” on Homer’s 1936 Social Security records.

Two decades later, Nora Elizabeth (Sieger) Sussdorff Van Horne died in San Mateo, California on 4 October 1942. Sadly, the life of her son, Homer, would end up being far shorter than her own.

On 15 November 1957, Dr. Homer Ignatius Van Horne was murdered in a rural area of southern California—a crime that was reported by The Valley Times in its 25 November 1957 edition:

Two San Fernando youths charged with murdering a staff doctor at Olive View Sanitorium in a lonely Pacoima canyon will be arraigned in Dept. 41, Superior Court, Dec. 10.

Delmont F. Johann Jr., 19, of 118 N. Maclay St., and Fred Rhoads, 18, of 2026½ Glen Oaks Blvd., appeared for preliminary hearing yesterday in the Glendale Municipal Court of Judge Kenneth A. White. He ordered the pair held without bail.

They are charged with murdering Dr. Homer Van Horne in Lopez Canyon on Nov. 15. Johann told police he stabbed the physician to death for money.

The youths were captured when they returned to the scene to bury the doctor. Johann, who told police that they had already dug the grave in a sandy wash, had borrowed the shovel from his parents.

The News-Pilot of San Pedro, California added, via its 16 November 1957 edition, that Dr. Homer Van Horne had been “found alive by a passing motorist at the top of a culvert on Lopez Canyon road,” but had “died before medical aid could be summoned.” That report also noted that he had “been on the staff of the Olive View Sanitarium north of Sylmar for about 20 years.” Olive View, according to the UCLA Medical Center, “was founded in the 1920s as a tuberculosis sanatorium.”

Documented as a resident of Greenville, Mercer County, Pennsylvania by the 1880 federal census enumerator, Frank Sieger was described as a “tin pedlar” [sic] by the census taker. Living with him were his wife and children: Nora, Emma, Daisey, and David.

Downtown Youngstown, Ohio, 1909 (courtesy of The Cleveland Press Collection, Michael Schwartz Library, Cleveland State University).

Franklin Sieger (surname also spelled as “Saeger” in various records) then relocated to Ohio sometime before 1890, according to federal military pension records which document that he filed for his U.S. Civil War Pension from Ohio on 25 July 1890.

According to the 1900 federal census, Frank Sieger resided at 231 East Boardman Street in Youngstown, Mahoning County, Ohio with his wife and their daughter Daisey; son Jessie, who had been born in December 1883, and was employed as a clerk at a butcher’s shop; and daughter Dot, who had taken the surname of “Solomon” when she had married sometime around 1897. That year’s census enumerator also confirmed that Frank Sieger was still employed as a tinsmith, that he and his wife had been married for thirty-three years, and that they had had five children together—all of whom were still alive.

By 1910, Franklin and Zidania Sieger, had relocated to the Youngstown home of their daughter, Daisy, who had married Michael McGinnis. But by 1920, Frank and Zidania had become lodgers in the Youngstown home of William Drake and his wife, Emma.

Frank Sieger subsequently passed away in Youngstown Ohio. Following his death on 11 December 1922, he was laid to rest at that city’s Oak Hill Cemetery. Just over a week later, his widow, Zidania, filed for her U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension from Ohio on 20 December 1920, according to U.S. Civil War Pension records.

Note: This death year of 1920 is also supported by the 1917 and 1918 obituaries of Frank Sieger’s siblings, Elizabeth (Sieger) Butz and James M. Sieger, which indicated that Frank was one of their surviving siblings and that his residence at that time was in Youngstown, Ohio.

Zidania Sieger soldiered on for a few more years. Suffering from various heart ailments, she died in Pittsburgh, Allegheny, Pennsylvania on 28 March 1928, and was then laid to rest at St. Peter’s Cemetery in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania on 2 April.

What Happened to the Sieger Brothers’ Mother and Other Siblings?

The Sieger brothers’ mother, Naomi (Kern) Sieger, who was known to family and friends as “Amy,” passed away on 2 September 1887, and was laid to rest beside their father at the Jordan Lutheran Cemetery in Orefield.

The Sieger brothers’ sister, Caroline, married Frank Henry Wilson (1846-1932) circa 1868. Two years later, the couple were residing in Catasauqua, Allen Township, Lehigh County, where Frank was employed as a carpenter. Also living with them at this time were daughters Margaret (aged two) and Isabelle Eva (1867), who was known to family and friends as “Bella” and would go on to wed Anthony George McAllister (1863-1943) in 1905. In 1880, the membership of their Catasauqua household was documented by the census enumerator as: Frank, Carolina, “Bella” (aged eleven), Catharine (aged four), Mary M. (1876-1953), who would later go on to wed William Edgar (1877-1908); and eight-month-old son Thomas J. Wilson (1879-1913).

By the turn of the century, Caroline (Sieger) Wilson and her husband were described as residents of Allen Township in Northampton County. They had welcomed the births of ten children, only five of whom were still alive at the time of the 1900 federal census. Living at home with them were: Bella; Thomas; George (1881-1952), who went on to marry Sarah A. McQuillan; and Joseph, who had been born in April 1885.

By 1910, their North Catasauqua household included Caroline and her husband, Frank; their sons, Thomas and George; and George’s sons, James (aged nine) and George (aged seven).

Caroline (Sieger) Wilson lived seven more years after the census enumerator’s visit that year. On 13 May 1917—exactly one month after her brother James M. Sieger passed away in Missouri, she succumbed to complications from endocarditis and “la grippe” at the age of seventy-six in North Catasauqua, Pennsylvania. Following funeral services held the next day at her home at 318 Liberty Street in Catasauqua, she was interred at the Allen-Union Cemetery in Northampton, Pennsylvania.

Matt Sieger would go on to become the manager of the Hotel Penn, 7th and Linden Streets in Allentown, Pennsylvania (shown here circa early 1900s, public domain).

Like their father and older brother Frank before them, Madison and Elias Sieger grew up to be tinsmiths. In 1870 they resided together at Madison’s home in North Whitehall Township, Lehigh County, where Madison, who was known as “Matt” to family and friends, lived with his wife, Emma Louise (Snyder) Sieger (1857-1935). According to federal census records that year, Matt Sieger had already amassed a personal estate of $1,000 (the equivalent of roughly $22,315 in 2022 dollars).

During this phase of his life, Matt Sieger founded a stove business in his hometown of Siegersville (now Orefield). He also welcomed the births, with his wife, of the following children: Jennie M. (1874-1961); Alice G. (1878-1948), who was born in Hazleton, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, and went on to wed Samuel F. Knelly (1868-1936) in 1898; and George Madison Sieger (1880-1943), who was born on 4 September 1880 and went on to marry Lottie M. Keichel (1891-1977).

As Matt’s family grew, his life diverged from that of Elias. Opting to leave the family trade of tinsmithing behind, he became a well-known businessman and hotelier, following a similar life path to his older brother, William H. Sieger.

Fortunately, Matt Sieger’s life would take a far different and happier turn. Having learned how to run a business from his stove sales, he became a tobacco salesman in Allentown, according to the 1880 federal census, and then became a successful livestock merchant (according to his obituary).

Opting to switch careers entirely after that, he entered the hospitality industry by securing employment with Allentown’s Snyder Hotel. Convinced that he could become a success in that field, Madison Sieger began to pave his new path as a hotelier. After working for a few years as the manager of the Cottage House in Freeland, Luzerne County, Pennsylvania, he bought and operated the Hazleton Hotel, which was located at 1 Broad Street in the 1st Ward of the City of Hazleton in Luzerne County, according to the federal census, which also documented that Matt Sieger and his son, George, employed roughly twelve hotel staff.

Following a long tenure with the Hazleton Hotel, he then returned to Allentown to assume responsibility for managing the Penn Hotel, which had opened in 1895 and was located at 7th and Linden Streets. He remained until 1904 when he and his son, George, purchased the Allen House at 2034 Main Street in Northampton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania.

He continued to live and work at the Allen House until his death there on 10 August 1919. Following funeral services at the Allen House at 2:30 p.m. on 14 August, he was laid to rest in a private ceremony at the Fairview Cemetery in Northampton. According to his obituary, which ran in The Morning Call of Allentown, the day after his death:

Madison Sieger, a widely known hotelman and drover, died at his home at Northampton at 11:30 p.m. yesterday [10 August 1919] of a complication of diseases, aged 73 years, 4 months and 4 days.

The deceased was born at Saegersville, the son of the late Joseph and Naomi (Kern) Sieger. In early life he conducted a stove business at Siegersville. He later came to this city [Allentown], where he was engaged in the buying and selling of livestock. Later he became employed at Snyder’s Hotel, in this city [Allentown], which gave him the idea of following a career as a proprietor of hotels.

His first enterprise was the Cottage Hotel at Freeland, where he made friends and proved to be an excellent manager. He then took over the management and ownership of the Hazleton Hotel, where he enjoyed a wide patronage for many years. He came closer to home and took charge of the Hotel Penn in this city [Allentown].

Fifteen years ago he and his son, George, purchased the Allen House at Northampton, which they have conducted with marked success.

He is survived by his wife, Anna, nee Snyder, and three children, George, Jennie and Alice, all of Northampton. Two brothers, Frank, of Pittsburgh, and Oliver, of Wayne, and a grandchild also survive. Funeral services will be held on Thursday afternoon at 2:30 o’clock, from his late home. Interment in Fairview Cemetery.

Diagnosed with Hodgkin’s Disease in 1941, Madison’s business partner and son, George Sieger, died at the Haff Hospital in Northampton, Pennsylvania on 27 February 1943, and was laid to rest at Northampton’s Fairview Cemetery on 3 March.

As indicated above, the Siegers’ brother, Elias, followed in the footsteps of their father and eldest Sieger sibling, Frank, by entering into the family business of tinsmithing with his older brother, Madison (“Matt”) Sieger. But unlike Matt, who chose to leave that trade sometime around the 1880s, Elias continued to work as a tinsmith, according to the 1880 federal census, which also documented that he resided with his wife, Louisa M. (Peter) Sieger (1852-1911), and their children in Coplay, Lehigh County.

Their children were: Annie Marie (1874-1933), who was born on 6 August 1874 and later wed Samuel Launbach/Laubach; Joseph (1875-1971), who was born in December 1875 and later wed Ada Schnurman; Harry (1877-1940), who was born in Coplay on 21 September 1877 and later wed Mamie Williams; Clara Louise (1880-1970), who was born in Coplay on 27 August 1880 and later wed Robert Beitel; Reuben Elias (1882-1892), who was born in Coplay on 1 April 1882, but sadly died at the age of ten on 29 July 1892; Mark Joel (1884-1915), who was born on 8 March 1884 and was known to family and friends as “Max”; Amy Catharine (1886-1976), who was born in Coplay on 7 April 1886 and went on to wed Percy Ruhe (1881-1962); Jeremiah Casper (1888-1933), who was born in Coplay on 27 March 1888 known to family and friends as “Jerry”; Effie Matilda (1890-1966), who was born in Coplay on 22 September 1890 and went on to wed William Sterrett Ker (1890-1941); Charles Matthew (1892-1954), who was born in Coplay on 13 November 1892; and Isabel Marie (1896-1970), who was born in Coplay on 11 January 1896 and went on to marry I. Forest Huddelson (1893-1965) in 1921.

Still residing in Coplay with his wife and children, Annie, Joseph, Harry, Clara, Max, Amy, Jerry, Effie, Charles and Isabel when the federal census enumerator arrived at his home in 1900, Eli Sieger was also still working as a tinsmith, as was his son, Joseph, while Annie and Harry were employed, respectively, as a dressmaker and clerk. Max, Amy, Jerry, Effie, and Charles were in school.

Eli Sieger would continue to practice his craft of tinsmithing for the remainder of his life. Suffering from myocarditis and a dilation of his heart, he died in Coplay on 1 March 1919, and was laid to rest at Mickleys Cemetery (now known as Saint John’s Union Cemetery) in Lehigh County on 4 March.

As indicated above, the Sieger brothers’ youngest sister, Lizzie, resided with brother William H. Sieger in 1870 at Allentown’s Eagle Hotel, where William was partnering with Levi Hottenstein in operating that establishment. But by 1880 (after William’s death), Lizzie and her husband, John D. Butz (1837-1889), a prominent Lehigh Valley businessman known for his successful retail shoe operation, had moved out and were residing at 132 North Second Street with her stepchildren: Raymond (1864-1936), who later became a physician; and eleven-year-old Minnie, who had been born sometime around 1869—the year that Lizzie’s husband had been widowed by his first wife.

Having married John Butz roughly nine years before she was widowed by him (in 1889), she remained at 132 North Second Street, according to the 1900 federal census. Ailing for many of her final years, she passed away at her home at 2:30 a.m. on 9 April 1918, and was laid to rest at that city’s Union-West End Cemetery. The Allentown Democrat reported on her passing in its 10 April edition as follows:

Mrs. Elizabeth A. Butz, widow of John D. Butz, died at her home, 132 North Seventh St., at 2:20 o’clock yesterday morning, following a long illness of a complication of diseases. She resided for many years at the home in which she died. Mrs. Butz was born at Siegersville and was the youngest child [sic] of Joseph and Amy Kern Sieger. She was the second wife of Mr. Butz, who was a leading shoe dealer in Allentown. He died 29 years ago in April. Mrs. Butz is survived by four brothers: Matt Sieger, Siegfried; Elias Sieger, Coplay; Oliver Sieger, Kane, Pa.; Frank Sieger, Youngstown, Ohio. Her death was the third in the family within a year, a sister, Mrs. Frank Wilson, of Catasauqua, and a brother, James, of San Jose, Mo. Having preceded her. The funeral will be held on Saturday at 2 p.m. with services at her home. Burial will be made in Union cemetery.

The Sieger brothers’ youngest sibling, Oliver Peter Sieger, also chose to follow in the footsteps of their father and oldest sibling, Frank, according to the 1880 federal census, which documented that he was employed as a tinsmith in North Whitehall Township, Lehigh County, where he resided with his wife Agnes (Smith) (1857-1935), who was known as “Priscilla.” Living with them were daughters, Annie (aged five), Sallie (aged three), and three-month-old Mayme E. Sieger, who was born on 7 March 1880 and would later wed Michael Francis Scanlon (1874-1956) in 1916.