First Lieutenant James F. Meyers, Company A, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, circa 1863 (public domain).

In 1860, about 13% of the U.S. population was born overseas—roughly what it is today. One in every four members of the Union armed forces was an immigrant, some 543,000 of the more than 2 million Union soldiers by recent estimates. Another 18% had at least one foreign-born parent. Together, immigrants and the sons of immigrants made up about 43% of the U.S. armed forces.

—Don H. Doyle, McCausland Professor of History at the University of South Carolina

James F. Meyers was one of those “one in every four members of the Union armed forces.” An emigrant from the Kingdom of Württemburg, he subsequently settled in northeastern Pennsylvania in the United States, where he made his home for the remainder of his life—save for the period of time he spent fighting to eradicate the brutal practice of chattel slavery in America while fighting to preserve the Union of his adopted homeland during the American Civil War.

A man who valiantly led men in battle during one of America’s darkest and most dangerous times, he was, for all intents and purposes, “just” a regular guy—a blue collar worker who supported his family on the wages of a painter and attended services at his local Lutheran Church on Sundays.

Formative Years

Born in the Kingdom of Württemburg (now Germany) on 10 November 1834, James F. Meyers was a son of John F. and Mary M. Myers (alternate spellings: Meiers, Meyers). He was raised and educated in a region of Europe that, while still largely agrarian, was also a region that was inhabited by people who had, historically, been witness to great periods of political, social and religious upheaval. According to historian James G. Chastain, during the 1840s, Württemburg “was still a predominantly agrarian state with many small and medium-sized towns, above all in its core area, and without legal and only minor social distinctions between town and country.”

Repeated division of inheritances made the small family farm the typical form of agriculture; the land was too thickly populated in relation to its productivity. Its membership in the German Customs Union and thereby consequent involvement in the more developed world economy threatened with the competition of foreign industry (small) artisans, producing for the local market. Thus everything was only superficially in order as the realm celebrated the 25th anniversary of the coronation of King Wilhelm I (1816-64) and the Constitution of 1819 in 1841 and 1844. The state debt of the Napoleonic period no longer burdened the country, the opposition in the legislature (Landtag) was weak, the new territories annexed forcefully to the new kingdom between 1803 and 1810 appeared integrated with the old domain. However, the general consciousness of a crisis and the discussion of “pauperism” also engulfed Wurtemberg [sic] and reached a crisis in the hunger riots of 1847. In church life the tensions between rationalism and pietism deepened among Protestants, and between the ultramontanism and rationalism among Catholics. The beginning of rail road construction by the state in 1845 changed the relationship between the government and parliament and between voters and deputies; the opposition increasingly looked across the state’s borders and demanded that the country’s problems be seen in the wider context of all Germany. To this extent, the 1840s anticipated the revolutionary events of 1848. In particular it was the experiences of 1847 which influenced 1848: the limited cooperation between government and opposition to combat anarchical undercurrents in the lower orders, the opposition hoping to exploit this violence for their own less radical objectives; they thought they could divert through political reforms the “specter of Communism,” which they also clearly recognized. They framed attainable modernizing impetus for Wurtemberg in new and better laws, reorganization of administration, reform of the constitution and not the least in creation of German unity.

By late February 1848, news of protests and riots elsewhere in Europe had reached Württemburg. In response, residents of the kingdom who were hoping for greater freedom began petitioning the king and members of his government to improve their lot—but initially kept their demands moderate in fear of sparking the same levels of violence that were roiling France during this time. The king’s response, however, was not what they had hoped for. Choosing to appoint conservatives rather than liberals to the new government that had recently been formed, the king was forced to adapt as members of the government and public reacted angrily and refused to follow directives issued by his new minister.

The king was then also pressed “to appoint oppositional leaders to a ‘March ministry,’ whose actual chief was Friedrich Römer.”

The new ministry resolutely set out on a double mission to carry out reforms and simultaneously to resist ‘anarchy.’ It called in the military against peasants who in some areas had swept away remnants of the feudal system with their own means, and it promised to enact the most important liberal and democratic reforms, above all by creating German unity assisting in calling together a German national constituent assembly. Römer was actively engaged in this from the beginning: he belonged to the small group who first proposed and prepared its organization; in addition he supported the diplomatic initiatives of a leader of the Hessian opposition, Heinrich von Gagern … directed the King of Prussia to take over the command of the future united German executive. Both initiatives ended differently than expected: the Viennese revolution in mid-March 1848 returned Austria to Germany; the Berlin revolution of March 18 made King Frederick William IV of Prussia ‘impossible’ for the envisioned role. The original plan to create German unity based on a reform of the German Confederation of 1815 by creation of a ‘German Parliament’ and a true executive foundered even before the opening of the German national assembly on May 18, 1848…. Römer and his ministry, as well as a majority of Wurtembergers for a long time, cooperated with enthusiasm in this effort until the bitter end on June 18, 1849 in Wurtemberg’s capital of Stuttgart when Römer ordered Wurtemberg’s soldiers to use force to prevent further meetings of the ‘rump parliament’ which had fled from Frankfurt to Stuttgart….

In addition, according to Chastain, “Religious differences (pietists or ultramontanes as opposed to rationalists) often were more important that political.”

However, a strong interest in politics developed quickly; already in June 1848 one could see that the majority of politically active men (women had no suffrage yet) stood further left than the deputies elected at the end of April, who in turn more often took their seats on the left than the right in the St. Paul’s Church. The Wurtembergers placed their hopes above all on the national assembly’s proposed ‘Bill of Rights of the German People,’ which included a thoroughgoing program of modernization of political and social conditions. Independent of this, was the pursuit of demands for industrialization….

Meanwhile, political leagues polarized the country. The handful of ‘fatherland leagues’ supported constitutional monarchy and conservative reform; the multiplicity of ‘Popular Unions’ were for more thoroughgoing reforms and for a democratization of the constitution. The leaders in their monthly newly elected central committee (Landesausschuss) were increasingly critical of the ‘March Ministry.’

As a result of the controversy in the national assembly over the continuation or end of the war with Denmark over Schleswig- Holstein, violence erupted in September 1848 in Frankfurt, in Baden, and in other parts of Germany, including Wurtemberg—but an attempted ‘march on Stuttgart’ failed. The ringleaders were arrested far from their objective, held long in prison, and finally ‘pardoned’ to emigrate to America. The name of the soon deceased ‘forty eighter’ remained forgotten and never eulogized….

At the apogee of the September crisis the legislature (Landtag) elected in May finally convened and began to consider a major program of laws. As 1848 ended—even before the imperial constitution was enacted—in Wurtemberg the ‘Bill of Rights of the German People’ was to be the basis of an extensive constitutional reform. The Chamber of Peers in the parliament should be dissolved and the remaining Lower House should be made up only of democratically elected deputies. These constitutional changes were to be enacted by a democratically elected ‘Constitutional Convention’; but before this convention could convene, the efforts in Wurtemberg to promulgate the Imperial Constitution approved in Frankfurt on March 28, 1849 plunged Swabia once more into a severe constitutional struggle. On one side stood King Wilhelm with a few followers, on the other side the March Ministry, almost the entire parliament, and the overwhelming majority of the politically active masses who articulated an opinion. And this despite the fact that with the imperial constitution the Frankfurt assembly also elected King Frederick William IV as hereditary German emperor, which only a few members of the protestant educated middle class (Bildungsbügertum) welcomed, whereas the mass of the protestant petty bourgeoisie and nearly all catholics disapproved, even the conservatives among them. The Wurtembergers did not battle for an emperor, rather for the bill of rights and the constitution’s intimately associated democratic electoral law. King Wilhelm finally had to give in to the united resistance of his people, his parliament and his government when the military also refused to support a planned coup d’etat. Wilhelm was the only German king conceding to support the Frankfurt imperial constitution, which hitherto only the minor states had ratified.

It was against this backdrop of anxiety and uncertainty that James F. Meyers made the difficult decision to leave all that he had come to know behind and emigrate in search of a more stable and secure future. Upon his arrival in the United States sometime during the early to mid-1850s, he chose to settle in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

In 1858, he wed Mary Hutt, a daughter Joseph and Mary Hutt (1838-1879), at St. John’s Lutheran Church in Easton on 1 February 1858. Their son, William Richard Meyers (1858-1890), was born later that same year—shortly before Christmas, on 20 December 1858. He was then baptized as a Lutheran in Easton on 5 June 1859.

By 1860, family patriarch James F. Meyers was employed as a painter and was residing with his wife, Mary, and their son, William Richard Meyers, in West Easton, Northampton County. As the nation’s horizon grew darker by the minute, clouded by the 20 December 1860 secession of South Carolina from the Union and the subsequent secessions of multiple southern states, James and Mary Meyers welcomed the Easton birth of a second son, Charles Wick Meyers (1861-1945), on 10 March 1861. He was subsequently baptized on 12 May of that same year.

American Civil War—Three Months’ Service

Among the earliest responders to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers “to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union, and the perpetuity of popular Government, and to redress wrongs already long enough endured” was twenty-eight-year-old German immigrant James F. Meyers. Traveling to what would later become known as Camp Curtin on the outskirts of Pennsylvania’s capital city, Harrisburg, he enrolled for Civil War military service on 20 April 1861, and was mustered in that same day as a first sergeant with Company B of the 1st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

* Note: Two days before President Abraham Lincoln issued his 15 April 1861 call for volunteer troops to help defend the nation’s capital (following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces), residents of the counties of Lehigh and Northampton in Pennsylvania “called a public meeting at Easton ‘to consider the posture of affairs and to take measures for the support of the National Government,’” according to Alfred Mathews and Austin N. Hungerford, authors of History of the Counties of Lehigh and Carbon, in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Worried about the worsening relations between America’s North and South, the citizens voted to establish and equip an entirely new military unit, one that would be readied for duty as quickly as possible. Several of the men in attendance that evening, including Charles Heckman and Samuel Yohe, had already begun recruiting local militia members and other volunteers to fulfill this charge and protect the nation’s capital if needed. Yohe, the owner-operator of a local distillery, mill and store in Easton who had also served his community as an associate judge, county treasurer and prothonotary, was the commanding officer of the Washington Grays, an Easton-based militia unit.

Yohe was ultimately commissioned as a colonel and placed in charge of the entire 1st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. His second-in-command was Tilghman H. Good, the native of Lehigh County who would subsequently go on to found the history-making 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry and who would, post-war, become a three-time mayor of the city of Allentown.

The same day that President Lincoln called for volunteer troops (15 April 1861), the community leaders who authorized the creation of what would become the 1st Pennsylvania Volunteers contacted Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin to volunteer the support of their local recruits to the Keystone State and nation. Three days later, these experienced militia members left hearth and home to head for Dauphin County.

* Note: The fact that First Sergeant James F. Meyers was mustered in as a sergeant rather than a simple private indicates that he had had previous military training—very likely prior to his emigration, while he was still residing in Württemburg. The fact that he was mustered in as a first sergeant indicates that his prospective commanding officers had determined that his military training and experience were so solid that he was not only fully capable of commanding men in combat, but that he was also well enough educated that he could handle the administrative responsibilities delegated to him by his immediate supervisor—B Company Captain Jacob Dachrodt. According to the United States Army, the “Army first sergeant is a specially-selected noncommissioned officer that is unparalleled in responsibilities and importance,” who, even today, is “the ‘lifeblood of the Army’ and ‘master trainer of the company,’ while affirming the unique relationship of confidence and respect that exists between a first sergeant and their company commander.” Among his duties, First Sergeant Meyers would have been expected to maintain B Company’s order book, which documented each of the orders that were issued to the company, as well as personnel rosters and records related to the receipt and disbursement of ammunition, clothing, food, and water.

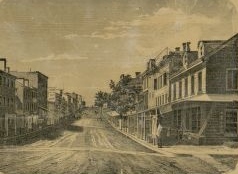

View of Baltimore, Maryland from the North, circa 1862 (E. Sachse & Co., U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Transported by Northern Central Railway cars with their regiment to Cockeysville, Maryland, the 1st Pennsylvanians then spent time at Camp Scott near York, Pennsylvania before being ordered to railroad guard duties along the rail lines between Pennsylvania and Druid Park in Baltimore, Maryland from 14-25 May.

From there, the 1st Pennsylvanians were assigned to Catonsville (25 May) and Franklintown (29 May) before being ordered back across the border with their regiment and stationed at Chambersburg (3 June). There, they were attached to the 2nd Brigade (under Brigadier-General George Wynkoop), 2nd Division (under Major-General William High Keim), in the Union Army corps commanded by Major-General Robert Patterson. Ordered to Hagerstown, Maryland on 16 June and then to Funkstown, the regiment remained in that vicinity until 22 June, when it was ordered to Frederick, Maryland.

Assigned with other Union regiments to occupy the town of Martinsburg, Virginia from 8-21 July (following the Battle of Falling Waters earlier that month), the 1st Pennsylvanians were subsequently ordered to Harpers Ferry on 21 July. Following the completion of their Three Months’ Service, they honorably mustered out on 23 July 1861 and returned home to their respective families and communities.

American Civil War—Three Years’ Service

Following his honorable discharge from the military, James F. Meyers returned home to his family in Easton. Knowing that the war was far from over, however, he decided that he could not remain on the sidelines as other men marched off to try to bring an end to the conflict. So, he re-enlisted.

Following his reenrollment in Easton on 15 August 1861, he re-mustered at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg just over a month later—on 16 September. This time, he was commissioned as the First Lieutenant of Company A in an entirely brand new regiment—the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, which had just been established on 5 August. Military records at the time described him as being 5’8” tall with brown hair, brown eyes and a fair complexion.

* Note: Company A was led by Richard A. Graeffe, who had performed his own Three Month’s Service with Company G, 9th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Commissioned as a captain upon his enlistment in April 1861, he served with the 9th Pennsylvania from 24 April 1861 until mustering out at Harrisburg, Dauphin County out on 29 July 1861. Graeffe then enlisted again on 16 September 1861, was again commissioned as a captain, and was placed in charge of Company A of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

According to A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers, authored by Lewis Schmidt, “The Easton Express reported on August 14 that … 33 year old Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, a merchant from Easton who would command Company A of the 47th, was recruiting at Glantz’s’ in Easton.” That saloon in Easton was operated by Charles Frederick William Glanz, an 1845 emigrant from Germany who had been appointed as captain of the Northampton County militia unit known as the “Easton Jaegers” during the late 1850s.

Following a brief light infantry training period at Harrisburg’s Camp Curtain, the men of Company A and the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Washington, D.C. where they were stationed at “Camp Kalorama” on Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, beginning 21 September. Henry D. Wharton, a Musician with the regiment’s C Company, wrote to the Sunbury American newspaper the next day with the following update:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

On 24 September 1861, Captain Richard Graeffe, First Lieutenant James F. Meyers and their men from Company A became members of the U.S. Army when they were officially mustered into federal service with the other members of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Three days later, the 47th Pennsylvania was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania was on the move again. Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen marched behind their Regimental Band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (165 steps per minute using 33-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated fairly close to the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (also known as “Baldy”), and were now part of the massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” for the large chestnut tree located within their lodging’s boundaries. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly 10 miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. Also around this time, companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left-wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops. In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday, 22 October, the 47th engaged in a Divisional Review, described by Schmidt as “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” Less than a month later, in his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic, Brannan], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review overseen by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.” As a reward—and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brannan obtained new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

But these frequent marches and their guard duties in rainy weather gradually began to wear the men down; a number of 47th Pennsylvanians fell ill with fever. Several contracted Variola (smallpox), which was also sickening Confederate troops stationed nearby, and were sent back to Union Army hospitals in Washington, D.C. At least two members of the regiment died from the pox while receiving treatment.

For this reason and because the war waged on, enrollments continued; by December 1861, a total of 101 men were listed on Company A’s roster.

1862

The City of Richmond, a sidewheel steamer which transported Union troops during the Civil War (Maine, circa late 1860s, public domain).

Next ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were then transported by rail to Alexandria before sailing the Potomac via the steamship City of Richmond to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped. They were then marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C.

The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the United States Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

By the afternoon of 27 January 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers commenced boarding smaller steamers and were ferried to the Oriental, with the officers boarding last. At 4 p.m., per the directive of Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, they steamed away for the Deep South—headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

Alfred Waud’s 1862 sketch of Fort Taylor and Key West, Florida (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

Upon their arrival in Key West in early February, they were ordered to garrison Fort Taylor. Members of the regiment were assigned either to barracks at Fort Taylor or tents on the city’s east side. The regimental chaplain, the Reverand William D. C. Rodrock described their quarters as “large and commodious two story buildings forming three sides of a quadrangle, the opening toward the sea.” Officers were housed in six of the fort’s structures near the parade ground while the enlisted men were housed in two other buildings or in Sibley tents.

Drilling daily in heavy artillery tactics, they also strengthened the federal installation’s fortifications. During the weekend of Friday, 14 February, they introduced their presence to local residents as the regiment paraded through the streets of the city. That Sunday, a number of soldiers from the resident mingled with locals at area church services.

According to a letter penned by Henry Wharton on 27 February 1862, the regiment commemorated the birthday of former U.S. President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation (first delivered in 1796), the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February. The festivities resumed two days later when the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards.” This was then followed by a concert by the Regimental Band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

The time spent here would not always be pleasant, however; multiple members of the regiment were ultimately felled by the Union Army’s deadliest foe—disease. Fourth Sergeant Andrew Bellis of Company A was one of those lost during this time. Increasingly unable to turn out for duty due to repeated bouts of illness, he was reduced in rank to private and finally succumbed to his ailments on 23 February 1862.

As winter turned to spring and the 47th Pennsylvanians were sent out beyond the city of Key West on various duty assignments, making them increasingly aware of just how different their new work environment was. According to Schmidt:

There was a slave camp about one mile from the military camps, where 150 Blacks were engaged in manufacturing salt; it was reported that 50,000 bushels of salt were made on the island each year by solar evaporation…. The manufacture of salt was terminated later in 1862, and was not restarted until 1864, to prevent any salt from the facility finding its way into the Confederacy….

Another building of note on the island of Key West during the war was the ‘slave barracoons’, used to house Blacks taken from captured slavery vessels, and described as being a long low building about 300 feet by 30 feet. Lt. Geety reported that there were 1500 slaves there at one time, and 400 died in four months [sic] time.

This 1856 map of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad shows the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina in relation to the towns of Beaufort, Charleston and Pocotaligo (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina from mid-June through July, they camped near Fort Walker before relocating to the Beaufort District, Department of the South, roughly thirty-five miles away. Frequently assigned to hazardous picket detail north of their main camp, which put them at increased risk from enemy sniper fire, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania became known for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” and “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan,” according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

On 12 September 1862, Colonel Tilghman Good and his adjutant, First Lieutenant Washington H. R. Hangen, issued Regimental Order No. 207 from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Headquarters in Beaufort, South Carolina:

I. The Colonel commanding desires to call the attention of all officers and men in the regiment to the paramount necessity of observing rules for the preservation of health. There is less to be apprehended from battle than disease. The records of all companies in climate like this show many more casualties by the neglect of sanitary post action then [sic] by the skill, ordnance and courage of the enemy. Anxious that the men in my command may be preserved in the full enjoyment of health to the service of the Union. And that only those who can leave behind the proud epitaph of having fallen on the field of battle in the defense of their country shall fail to return to their families and relations at the termination of this war.

II. All the tents will be struck at 7:30 a.m. on Monday, Wednesday and Saturday of each week. The signal for this purpose will be given by the drum major by giving three taps on the drum. Every article of clothing and bedding will be taken out and aired; the flooring and bunks will be thoroughly cleaned. By the same signal at 11 a.m. the tents will be re-erected. On the days the tents are not struck the sides will be raised during the day for the purpose of ventilation.

III. The proper cooking of provisions is a matter of great importance more especially in this climate but have not yet received from a majority of officers of the regiment that attention that should be paid to it.

IV. Thereafter an officer of each company will be detailed by the commander of each company and have their names reported to these headquarters to superintend the cooking of provisions taking care that all food prepared for the soldiers is sufficiently cooked and that the meats are all boiled or seared (not fried). He will also have charge of the dress table and he is held responsible for the cleanliness of the kitchen cooking utensils and the preparation of the meals at the time appointed.

V. The following rules for the taking of meals and regulations in regard to the conducting of the company will be strictly followed. Every soldier will turn his plate, cup, knife and fork into the Quarter Master Sgt who will designate a permanent place or spot for each member of the company and there leave his plate & cup, knife and fork placed at each meal with the soldier’s rations on it. Nor will any soldier be permitted to go to the company kitchen and take away food therefrom.

VI. Until further orders the following times for taking meals will be followed Breakfast at six, dinner at twelve, supper at six. The drum major will beat a designated call fifteen minutes before the specified time which will be the signal to prepare the tables, and at the time specified for the taking of meals he will beat the dinner call. The soldier will be permitted to take his spot at the table before the last call.

VII. Commanders of companies will see that this order is entered in their company order book and that it is read forth with each day on the company parade. All commanding officers of companies will regulate daily their time by the time of this headquarters. They will send their 1st Sergeants to this headquarters daily at 8 a.m. for this purpose.

Great punctuality is enjoined in conforming to the stated hours prescribed by the roll calls, parades, drills, and taking of meals; review of army regulations while attending all roll calls to be suspended by a commissioned officer of the companies, and a Captain to report the alternate to the Colonel or the commanding officer.

At 5 a.m., Commanders of companies are imperatively instructed to have the company quarters washed and policed and secured immediately after breakfast.

At 6 a.m., morning reports of companies request [sic] by the Captains and 1st Sgts and all applications for special privileges of soldiers must be handed to the Adjutant before 8 a.m.

By Command of Col. T. H. Good

W. H. R. Hangen Adj

In addition, First Lieutenant and Regimental Adjutant Hangen clarified the regiment’s schedule as follows:

- Reveille (5:30 a.m.) and Breakfast (6:00 a.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Guard (6:10 a.m. and 6:15 a.m.)

- Surgeon’s Call (6:30 a.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Company Drill (6:45 a.m. and 7:00 a.m.)

- Recall from Company Drill (8:00 a.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Squad Drill (9:00 a.m. and 9:15 a.m.)

- Recall from Squad Drill (10:30 a.m.)

- Dinner (12:00 noon)

- Call for Non-commissioned Officers (1:30 p.m.)

- Recall for Non-commissioned Officers (2:30 p.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Squad Drills (3:15 p.m. and 3:30 p.m.)

- Recall from Squad Drill (4:30 p.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Dress Parade (5:10 p.m. and 5:15 p.m.)

- Supper (6:10 p.m.)

- Tattoo (lights out, 9:00 p.m.) and Taps (9:15 p.m.)

Then as the one-year anniversary of the 47th Pennsylvania’s departure from the Great Keystone State dawned, thoughts turned to home and Divine Providence as Colonel Tilghman Good issued Special Order No. 60 from the 47th’s Regimental Headquarters in Beaufort, South Carolina:

The Colonel commanding takes great pleasure in complimenting the officers and men of the regiment on the favorable auspices of today.

Just one year ago today, the organization of the regiment was completed to enter into the service of our beloved country, to uphold the same flag under which our forefathers fought, bled, and died, and perpetuate the same free institutions which they handed down to us unimpaired.

It is becoming therefore for us to rejoice on this first anniversary of our regimental history and to show forth devout gratitude to God for this special guardianship over us.

Whilst many other regiments who swelled the ranks of the Union Army even at a later date than the 47th have since been greatly reduced by sickness or almost cut to pieces on the field of battle, we as yet have an entire regiment and have lost but comparatively few out of our ranks.

Certain it is we have never evaded or shrunk from duty or danger, on the contrary, we have been ever anxious and ready to occupy any fort, or assume any position assigned to us in the great battle for the constitution and the Union.

We have braved the danger of land and sea, climate and disease, for our glorious cause, and it is with no ordinary degree of pleasure that the Colonel compliments the officers of the regiment for the faithfulness at their respective posts of duty and their uniform and gentlemanly manner towards one another.

Whilst in numerous other regiments there has been more or less jammings and quarrelling [sic] among the officers who thus have brought reproach upon themselves and their regiments, we have had none of this, and everything has moved along smoothly and harmoniously. We also compliment the men in the ranks for their soldierly bearing, efficiency in drill, and tidy and cleanly appearance, and if at any time it has seemed to be harsh and rigid in discipline, let the men ponder for a moment and they will see for themselves that it has been for their own good.

To the enforcement of law and order and discipline it is due our far fame as a regiment and the reputation we have won throughout the land.

With you he has shared the same trials and encountered the same dangers. We have mutually suffered from the same cold in Virginia and burned by the same southern sun in Florida and South Carolina, and he assures the officers and men of the regiment that as long as the present war continues, and the service of the regiment is required, so long he stands by them through storm and sunshine, sharing the same danger and awaiting the same glory.

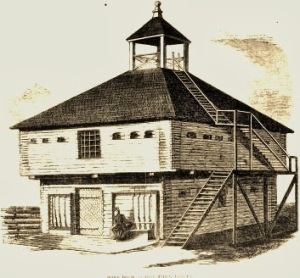

Union Navy’s base of operations, Mayport Mills, circa 1862 (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, public domain).

As September waned, they were sent on a return expedition to Florida. During this time, First Lieutenant James F. Meyers and his Company A subordinates participated with the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff from 1 to 3 October. Commanded by Brigadier-General Brannan, the 1,500-plus Union force disembarked at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek from troop carriers guarded by Union gunboats. Taking the point, the 47th led the brigade through twenty-five miles of dense, pine forested swamps populated with dangerous snakes and alligators. When it was all over, the brigade had forced the Confederates to abandon their artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, and paved the way for the Union to occupy the town of Jacksonville, Florida for a second time.

Integration of the Regiment

From early to mid-October 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania made history as it became an integrated regiment, adding to its muster rolls several young Black men who had endured plantation enslavement in Beaufort, South Carolina. Among those new soldiers were sixteen-year-old Abraham Jassum, thirty-three-year-old Bristor Gethers and twenty-two-year-old Edward Jassum.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army’s map of the Pocotaligo-Coosawhatchie Expedition, South Carolina, 22 October 1862. Blue Arrow: Mackay’s Point, where the U.S. Tenth Army debarked and began its march. Blue Box: Position of Union troops (blue) and Confederate troops (red) in relation to the Pocotaligo bridge and town of Pocotaligo, the Charleston & Savannah Railroad, and the Caston and Frampton plantations (blue highlighting added by Laurie Snyder, 2023; public domain; click to enlarge).

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers engaged Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point, the men of the 47th were placed on point once again, but they and their fellow 3rd Brigaders were less fortunate this time.

Picked off by snipers while on the move toward the Pocotaligo Bridge, they also faced massive resistance from a heavily entrenched and fortified Confederate battery that opened fire on the Union troops as they entered and crossed a clearing. Those headed for the higher ground of the Frampton Plantation fared no better, encountering artillery and infantry in the midst of the surrounding forests.

Bravely, the Union regiments grappled with the Confederates where they found them, pursuing enemy troops for four miles as they retreated to the bridge, where the 47th then relieved the 7th Connecticut. But the Confederates were just too well fortified. After two hours of intense fighting in an unsuccessful attempt to take the ravine and bridge, sorely depleted ammunition supplies forced the 47th’s withdrawal to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th were significant. Two officers and eighteen enlisted men died; two officers and an additional 114 enlisted men were wounded. Among those who were killed or mortally wounded were the commanding officers of Companies G, H and K, Captain Charles Mickley, First Lieutenant William W. Geety and Captain George Junker. Miraculously, Geety survived., following multiple surgeries.

The 47th Pennsylvania subsequently returned to Hilton Head on 23 October, where members of the regiment served as the funeral honor guard for the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South, General Ormsby M. Mitchel, who died from yellow fever on 30 October. Members of the 47th Pennsylvania were given the high honor of firing the salute over his grave.

1863

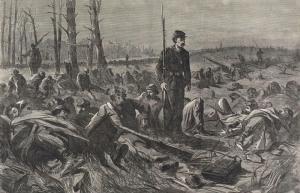

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

From March to December of 1863, Captain Graeffe, First Lieutenant Meyers and the men of A Company were stationed with the 47th Pennsylvania at Fort Taylor, along with members of Companies B, C, E, G, and I. (Companies D, F, H, and K were stationed at Fort Jefferson off Florida’s coast in the Dry Tortugas.) Once again, men from the 47th were assigned to fell trees, build roads and continue strengthening the facility’s fortifications.

In addition, they were also sent out on skirmishes.

The time spent in Florida by the men of Company A and their fellow Union soldiers was notable not just for these reasons—but for their commitment to preserving the Union. Many of the 47th Pennsylvanians who could have returned home, their heads held high upon expiration of their respective terms of service, chose instead to re-enlist in order to finish the fight.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th was ordered to expand the Union’s reach further. Captain Graeffe and a group of men from A Company were assigned to special duty that involved taking a detachment up north to Fort Myers and beyond to conduct raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. Abandoned in 1858 after the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians, the fort was ordered to be reclaimed and revitalized in 1864 by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade while also offering shelter for pro-Union supporters and those fleeing Rebel troops, including Confederate Army deserters and escaped slaves. According to Schmidt:

Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded a ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard. Lt. Harris was directed to tow the Matchless if necessary.

Punta Rassa was probably the location where the troops disembarked, and was located on the tip of the southwest delta of the Caloosahatchee River … near what is now the mainland or eastern end of the Sanibel Causeway… Fort Myers was established further up the Caloosahatchee at a location less vulnerable to storms and hurricanes. In 1864, the Army built a long wharf and a barracks 100 feet long and 50 feet wide at Punta Rassa, and used it as an embarkation point for shipping north as many as 4400 Florida cattle….

Capt. Graeffe and company were disembarked on the evening of January 7, and Gen. Woodbury ordered the company to occupy Fort Myers on the south side of the Caloosahatchee, about 12 miles from its mouth and 150 miles from Key West. Shortly after, [a detachment of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company stationed on Useppa Island] was also ordered to proceed to Fort Myers and join the main body of Company A, the entire command under direct orders of the General who was in the area…. Gen. Woodbury returned to Key West on the Honduras prior to January 19, and the command was left in charge of Capt. Graeffe who dispatched various patrols in search of refugees for enlistment and for activities involving Confederate cattle shipments.

Company A’s muster roll provides the following account of the expedition under command of Capt. Graeffe: ‘The company left Key West Fla Jany 4. 64 enroute to Fort Meyers Coloosahatche River [sic] Fla. were joined by a detachment of the U.S. 2nd Fla Rangers at Punta Rossa Fla took possession of Fort Myers Jan 10. Captured a Rebel Indian Agent and two other men.’

Schmidt notes that Graeffe’s hand drawings show there were roughly 12 buildings “primarily situated along the river, with a log palisade protecting those portions not bounded by the Caloosahatchee; the whole in a densely wooded area and entered through an opening on the southeast protected by the river on the west near the area of the wharf, and a log blockhouse on the east.”

An 1856 survey of the fort contained in the Federal Register “suggest that the fort’s wooden stockade ran from just east of Broadway to just east of Royal Palm, and from Main Street on the south to the river bank, which meandered along what is Bay Street today,” according to Tom Hall, creator of a website about the arts in Southwest Florida:

It consisted of as many as three dozen hewn pine buildings which included officers’ quarters … barracks, administration offices, a 2½-story hospital with plastered rooms, warehouses for the storage of munitions and general supplies, a guard house … blacksmith’s and carpenter’s shops, a kitchen, bakery, laundry, a sutler’s store, stables for horses and mules, a gardener’s shack, and even a bowling alley and bathing pier and pavilion.

It also boasted a pier nearly 700 feet long that had wide dock and rails that enabled the soldiers to bring in supplies by tram without having to lighter them ashore. The buildings were sided and topped by cedar shingles shipped in from Pensacola and Apalachicola, together with doors, windows and flooring. The interior featured parade grounds, a carefully-tended velvety lawn, two immense vegetable gardens, rock-rimmed river banks, shell walks, lush palms and even citrus trees.

Also according to Hall:

By the time Captain Richard A. Graeffe and his soldiers arrived at the fort, most of the wood stockade had disappeared, so he ordered his men to construct an earthen wall 15 feet wide by 7 feet tall. Three guard towers were also constructed: one where the hospital had been; a second by the garden and bowling alley; and the third between the stables and riverside warehouse. Then Captain Graeffe sent his troops across the river to begin rounding up the herds of scrub cows being raised by ranchers between Punta Gorda and Tampa. As they did, resistance began to grow. Captain Graeffe realized he needed reinforcements and Companies D and I of the [U.S. Colored Troop’s] 2nd Regiment were brought up from Fort Zachary Taylor in Key West.

A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documents the time of Richard Graeffe and the men under his Florida command this way:

A small contingent of 20 men and two officers from the Pennsylvania 47th Regiment, led by Captain Henry Crain of the 2nd Regiment of Florida, arrived at the fort on January 7, 1864. A short time later, the party was joined by another small detachment of the 47th under the command of Captain Richard A. Graeffe. Over a short period, increasing reinforcements of the fort led to increasing cattle raids throughout the region. A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.

Early on, according to Schmidt, Captain Graeffe sent the following report to Woodbury:

“At my arrival hier [sic] I divided my forces in three detachment, viz one at the Hospital one into the old guardhouse and one into the Comissary [sic] building, the Florida Rangers I quartered into one of the old Company quarters, I set all parties to work after placing the proper pickets and guards at the Hospital i have build [sic] and now nearly finished a two story loghouse of hewn and square logs 12 inches through seventeen by twenty-two fifteen feet high with a cupola onto the roof of six feet high and at right angle with two lines of picket fences seven feet high. i shall throw up a half a bastion around it as soon as completed. around the old guardhouse i have thrown up a bastion seven feet through at the foot and three feet on the top nine feet high from the bottom of the ditch and five on the inside. I also build [sic] a loghouse sixteen by eighteen of two storys [sic] Southeast of the Commissary building with a bastion around it at right angles with a picket fence each bastion has the distance you recomandet [sic] from the loghouses 20 feet on the sides and 20 to the salient angle, i caused to be dug a well close to bl. houses and inside of the bastions at each Station inside they are all comfortable fitted up with stationary bunks for the men without interfering with the defence [sic] of the work outside of the Bastions and inside the picket fense i have erected small kitchens and messrooms for each station, i am building now a guardhouse build [sic] of square hewn logs sixteen by sixteen two storys high the lower room to be used for the guard and the upper one as a prison, the building to be used for defence [sic] (in case of attack) by the Rangers each work is within view and supporting distance from the other; Capt. Crane with a detachment of his men repaired the wharf, which is in good condition now and fit for use, the bakehouse i got repaired, and the fourth day hier [sic] we had already very good fresh bread; the parade ground is in a good condition had all the weeds mowed off being to [sic] green to burn. i intend to fit up a schoolroom and church as soon as possible.”

Muster rolls for Company A from this period noted that “a detachment of 25 men crossed over to the north west side of the river” on 16 January and “scoured the country till up to Fort Thompson a distance of 50 miles,” where they “encountered a Rebel Picket who retreated after exchanging shots.” Making their way back, they swam across the river, and reached the fort on 23 January. Meanwhile, while that group was still away, Captain Graeffe ordered a smaller detachment of eight men to head out on 17 January in search of cattle. Finding only a few, they instead took possession of four barrels of Confederate turpentine, which were later disposed of by other Union troops.

Graeffe’s men also captured three Confederate sympathizers at the fort, including a blockade runner and spy named Griffin and an Indian interpreter and agent named Lewis. Charged with multiple offenses against the United States, they were transported to Key West, where they were kept under guard by the Provost Marshal—Major William Gausler, third-in-command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

This phase of duty lasted until sometime in February of 1864. The detachment of the 47th which served under Graeffe at Fort Myers is labeled as the Florida Rangers in several publications, including The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, prepared by Lieutenant Colonel Robert N. Scott, et. al. (1891). Several of Graeffe’s hand drawn sketches of Fort Myers were published in 2000 in Images of America: Fort Myers by Gregg Tuner and Stan Mulford.

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had already left on the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reconstituted regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.

But they had missed the two bloodiest combat engagements that the 47th Pennsylvania would endure during the Red River Campaign—the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield on 8 April and the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April. According to Schmidt, Company A was soon ordered to return the Confederate prisoners to New Orleans, and officially ended their detached duty on 27 April when they rejoined the main regiment’s encampment at Alexandria.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” for the Union officer who oversaw its construction, Lt.-Col. Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

This means that the men from Company A also missed a third combat engagement—the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry”), which took place on 23 April. They were available to assist with their regiment’s next major engagement, however. From late April through mid-May, they helped erect Bailey’s Dam on the Red River near Alexandria. In a letter penned from Morganza, Louisiana on 29 May, Henry Wharton described their mission and the weeks that followed:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits [sic] on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

On Sunday, May 15, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad wherewith the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired and we advanced ‘till dark, when the forces halted for the night, with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

Having entered Avoyelles Parish, they “rested on their arms” for the night, half-dozing without pitching their tents, but with their rifles right beside them. They were now positioned just outside of Marksville, Louisiana on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, the infantry advanced in line until they reached Mousoula [sic], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of our army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

After the surviving members of the 47th made their way through Simmesport and into the Atchafalaya Basin, they moved on to Morganza, where they made camp again. According to Wharton, the members of Company C were sent on a special mission which took them on an intense 120-mile journey:

Company C, on last Saturday was detailed by the General in command of the Division to take one hundred and eighty-seven prisoners (rebs) to New Orleans. This they done [sic] satisfactorily and returned yesterday to their regiment, ready for duty. While in the City some of the boys made Captain Gobin quite a handsome present, to show their appreciation of him as an officer gentleman.

While encamped at Morganza, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania in Beaufort, South Carolina (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864. The regiment then moved on once again, and arrived in New Orleans in late June.

Among those from A Company who did not survive the Red River experience were: Private Josiah Stocker, who died at the Union’s General Hospital in New Orleans on 17 May 1864 and Private Jacob Trabold, who died in Morganza on 27 June. Privates George Bohn and George Bollan lost their respective battles on 20 and 28 June. Left behind while their regiment headed north, Privates J. Williamson and Michael Andrew died on 13 and 14 July.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Still able and willing to fight after their time in Bayou country, the surviving soldiers of Company A and the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies C, D, E, F, H, and I steamed for the Eastern Theater of war aboard the McClellan beginning 7 July 1864.

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, they joined up with Union Major-General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July 1864. There, they fought in the Battle of Cool Spring and, once again, assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah from August through November of 1864, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were next assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, Virginia in early August 1864, and engaged in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville and other locations within the vicinity (Middletown, Charlestown and Winchester) as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces against those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in the Battle of Berryville, Virginia and engaged in related post-battle skirmishes with the enemy over subsequent days.

But by now, First Lieutenant James F. Meyers had decided that he had seen enough of death and destruction. Having completed the terms of his initial three-year service contract, he opted to be honorably discharged at Berryville on 18 September 1864.

Return to Civilian Life

View of Easton from Phillipsburg Rock, circa 1860-1862 (James Fuller Queen, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

Following his honorable discharge from the military, James F. Meyers returned to his adopted hometown of Easton, where he resumed work as a painter. Residing with him during this time were his wife, Mary, and their sons, William Richard Meyers and Charles Wick Meyers. By 1866, the Meyers household had expanded again to include a daughter, Margaret Magdalena, who had been born in Easton on 29 March of that year (1866-1907) and was known to family and friends as “Maggie.”

But by 1868, James F. Meyers was in failing health. On 11 April of that year, he filed for, and was subsequently awarded, a U.S. Civil War Pension in recognition of the health problems he was having.

Still employed as a painter by 1870, James F. Meyers continued to grow both his business and his family. Another daughter, Matilda, arrived in May 1870. That same year, his real estate and personal property were valued at $3,300 by the federal census enumerator (roughly $77,535 in 2023 dollars).

Death and Interment

Despite having survived the hardships of emigration, resettlement, and then the American Civil War, James F. Meyers was not strong enough to defeat the grim reaper when he came calling. Like so many of his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, his immune system was weakened by the stress of grueling marches and intense combat, as well as the exposure to multiple tropical diseases during the long conflict. Barely a decade after the war’s end, he was gone.

Following his death in Northampton County on 22 August 1875, he was interred at the Easton Cemetery. He was still just in his early forties.

What Happened to the Wife and Children of James F. Meyers?

Last Will and Testament of Mary A. (Hutt) Meyers, widow of First Lieutenant James F. Meyers, 6 September 1879, p. 1 (Clerk of the Orphans Court of Northampton County, Easton, Pennsylvania, probated 15 September 1879, public domain; click to enlarge).

Following the death of her husband, Mary (Hutt) Meyers continued to reside in Easton with her children, doing her best to keep the family going during a precarious time. By late 1877, she decided that she needed help to keep her family afloat, and filed for a U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension on 19 December—a pension that was eventually granted after she was forced to jump through a number of bureaucratic hoops. Sadly, though, the stress of caring for five children as a single parent gradually took its toll. She died in Easton in September 1879, and was laid to rest beside her husband at the Easton Cemetery. Like her husband before her, she too was only in her early forties.

Following the death of Mary (Hutt) Meyers, her children were placed into the care of her sister-in-law, Mary (Meyers) Ulmer. Per her last will and testament, which was dated 6 September 1879 and entered into probate on 15 September, during which time she was declared to be of sound mind:

I, Mary A. Meyers, widow of James F. Meyers, late of the Borough of Easton, in the County of Northampton and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania do make and publish this my last will and testament, as follows, to wit: First, I direct my executor, hereinafter named, to pay all of my just debts and funeral expenses as convenient after my death. Second: I give, devise, and bequeath all of my estate, both real and personal to my Executor, hereinafter named, to hold to him and his successor in the trust, upon and for the following uses and trusts, that is to say, that the entire income arising from my estate be paid to Mary Ulmer as the Guardian of my children, until the first day of March Eighteen hundred and ninety-three, upon which day, or as soon thereafter as can possibly be done, I direct my Executor to convert my said estate into money, or its equivalent, and divide the same between my Children William R. Meyers, Charles W. Meyers, Margaret M. Meyers, Matilda E. Meyers, Louisa N. Meyers, and John Titus Meyers, share and share alike. The heirs of such as may be deceased at the time of the distribution to take such share as the parent would have been entitled to if living. Third: I hereby nominate, constitute and appoint Mary Ulmer, sister of my deceased husband, Guardian of the persons and income accruing to my said children. Fourth, Should my said Executor at any time deem it necessary to convert my real estate into money, I hereby authorize him to do so after he shall have received authority from the Orphans Court of this County to do so, and in case of such sale, the money received from the sale shall be invested in the name of my estate, all moneys received from other sources shall at all times be invested in the name of my estate. Fifth, I hereby authorize my Executor at any time my said real estate may be sold, to execute to the purchaser or purchasers thereof full and sufficient deeds for the same under his hand and seal. Lastly I nominate, constitute and appoint Lewis Uhler, of Easton, to be the Executor of this my last Will and Testament, hereby revoking all former wills by me at any time heretofore made. In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand and seal this sixth day of September A.D. Eighteen hundred and seventy-nine. Mary A. Meyers [her mark X and seal]

View from Matthew Brady’s Center-Market Studio, Washington, D.C., 1880s (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

William Richard Meyers, the first-born child of James F. and Mary (Hutt) Meyers, led a life of even greater adventure than his father. During the early 1870s, presumably while his father was still alive, he enlisted in the United States Navy, and was assigned to serve as an apprentice aboard the U.S. Constitution, which was being operated as a training vessel for the navy. He was just fourteen years old at the time of his enlistment. By the age of twenty-two, he had been appointed to the rank of seaman gunner, a position he continued to hold until 1884, when he resigned and returned to civilian life.

On 16 October of that same year (1884), he wed Gertrude I. Auguste in Washington, D.C., and subsequently resided there with her and their three children on I Street. During this time, he was employed as a laborer, working as a painter and then as a sailmaker. He was also active in multiple civic and social organizations, including the Grand Lodge of Oddfellows, the Harmony Lodge and the Independent Order of Odd Fellows’ Magenenu Encampment. Tragically, like his parents before him, his life was a short one. Felled by what was described by area newspapers as “a short, but painful illness, he died in Washington, D.C. at 8:30 p.m. on 8 September 1890. Following funeral services that were conducted at his home at 3 p.m. on 11 September, he was laid to rest at that city’s Congressional Cemetery. He was still just in his early thirties at the time of his death. His widow directed newspapers to publish the following tribute in his honor:

A precious one from us has gone,

A voice we loved is stilled,

A place is vacant in our home,

Which never can be filled.

God, in his wisdom, has recalled

The boon his love had given;

And though the body moulders here,

The soul is safe in Heaven.

Ely Building and adjacent laboratory, Jefferson Medical College and Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1881 (public domain).

Meanwhile, the Meyers’ second child, Charles Wick Meyers, relocated to the Philadelphia area, where he ultimately found work as a janitor at Jefferson Hospital. Sometime around 1885, he wed Ella Vickery. Together, they welcomed the births of daughter Florence, in August 1891, and son Howard, in July 1895. In 1900 and 1910, their household also included Richard Vickery, Ella’s brother, but by 1920, the household had shrunk to include just Charles, Ella and Howard. A widower by the mid-1920s, Charles W. Meyers remarried in Philadelphia in 1928, taking as his second wife, Anna L. Herley. Suffering from chronic nephritis, he died in Philadelphia after a long, full life in February 1945, and was buried at the Arlington Cemetery in Drexel Hill, Pennsylvania.