Roster: Company K, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers

History of Company K

1861-1862

Alma Pelot’s photo of the Confederate flag flying above Fort Sumter, 16 April 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Company K was raised with the intent of being an all-German company. Its founder, George Junker, was a 26-year-old, proud native of Germany who lived and worked as a tombstone carver in Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, and served as a Quartermaster Sergeant with the Allen Infantry at the dawn of the Civil War. Also known as the “Allen Guards,” that group of soldiers was commanded by Captain Thomas Yeager and became the first of the Allentown militia units (and one of the first five Pennsylvania units) to respond to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteers to defend the nation’s capital following the Fall of Fort Sumter in mid-April 1861.

Sergeant Junker and his fellow Allen Infantrymen were primarily engaged in the performance of guard duty during their Three Months’ service, according to various historical accounts of the period, and served from 18 April until their unit was honorably discharged on 23 July 1861. They and Pennsylvania’s other early defenders were praised by the Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives for pushing their way through an angry mob of Confederate sympathizers in Baltimore to quickly reach and safeguard Washington’s residents.

* Note: During the aforementioned mob attack in Baltimore, Sergeant Junker was briefly arrested by Confederate sympathizers and held as a prisoner; pretending to be a Union deserter, he persuaded his captors to release him so that he could join the Confederate Army. Once free, however, he made his way back to his fellow Allen Infantrymen and continued to serve the Union honorably for the duration of his service.

George Junker announces formation of Civil War company of German/German-American soldiers (Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, 7 August 1861, public domain).

Following his return home to the bucolic Lehigh Valley in Pennsylvania and his adopted hometown of Allentown, Sergeant George Junker promptly began recruiting men to join a new company of soldiers for a three-year tour of duty. Junker made a concerted effort to reach out to German immigrants, as well as naturalized and native born German-Americans for help. Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, the Lehigh Valley’s Allentown-based, German language newspaper, praised him for his initiative in its 7 August 1861 edition. Roughly translated, the announcement read:

It’s good to hear, that Sergeant Junker, of this city, is bringing a new German company of the Lehigh Valley along under the terms of recruitment for the duration of the war. It will be particularly sweet to him if such Germans already here or abroad, who have served as soldiers, sign up immediately for him, and join the company. It can be noted that Sergeant Junker, who recently returned from the scene of the war, has done important services for the Union side in this time, and has all capabilities that are necessary for a Captain. We wish him the best luck for his company.

Sergeant Junker conducted most of his outreach within Allentown’s boundaries, but also drew soldiers from Guthsville, Hazleton, Longswamp, and Saegersville, and other neighboring communities. A number of his prospects were, as he had been, early responders to President Lincoln’s call for volunteers. While some served with the Allen Infantry, others had enlisted with different regiments, but after completing their Three Months’ Service, almost all realized—as did George Junker—that the war was not yet won. So, when Sergeant Junker approached them, many enthusiastically signed up in August and September of 1861 as members of Company K with the newly formed 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry—a regiment which had been founded by Allentown’s own Colonel Tilghman H. Good.

Blacksmiths, farmers, miners, saddlers, shoemakers and other laborers officially mustered in for their three-year tours of duty with the 47th Pennsylvania at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County on 17 September 1861. That same day, Sergeant George Junker was promoted to the rank of Captain, and was placed in charge of his recruits. He would go on to lead Company K from its inception until 22 October 1862 when he was mortally wounded during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina.

* Note: Although his new recruits could not know it as they enlisted, the majority of K Company soldiers would be led by a succession of commanding officers before the long war was over: the aforementioned Captain George Junker; Captain Charles W. Abbott, a First Defender who had re-enlisted with the 47th after protecting the nation’s capital during his Three Months’ Service, who then received a battlefield promotion with the 47th when Captain Junker was wounded in action, and then held that position as K Company’s captain until receiving a promotion to the regiment’s central command staff; and Captain Matthias Miller, who had risen steadily up from the rank of Corporal with Company K until receiving his own promotion to the rank of Captain, K Company in 1865.

Following a brief training period in light infantry tactics at Camp Curtin, the men of Company K and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians left William Schubert behind to convalesce at the camp’s hospital, hopped aboard a train at the Harrisburg depot, and were transported by rail to Washington, D.C. Stationed roughly two miles from the White House, they pitched tents at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown beginning 21 September.

* Note: The training and departure process was clearly a hectic one. Private Elias Reidy (alternate spelling: “Ready”) was felled by “friendly fire” from an errant pistol shot; hospitalized, he was discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability just over two months later on 26 November. Meanwhile, Private William Schubert was incorrectly labeled a deserter when the scribe in charge of the regiment’s muster rolls failed to update his entry to note that he had been left behind at the camp hospital for disease-related treatment as the regiment moved on to the nation’s capital. Spelling variants of the private’s surname (Schubard, Schubert) also likely contributed to this confusion.

On 22 September, Henry D. Wharton, a Musician with the regiment’s C Company, penned the following update to his hometown newspaper, the Sunbury American:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

Acclimated somewhat to their new way of life, the soldiers of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry finally became part of the U.S. Army when they were officially mustered into federal service on 24 September.

On 27 September—a rainy day, the 47th Pennsylvania was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania was on the move again. Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen marched behind their regimental band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (165 steps per minute using 33-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated fairly close to the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (also known as “Baldy”), and were now part of the massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” for the large chestnut tree located within their lodging’s boundaries. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly 10 miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a mid-October letter home, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin (the leader of C Company who would be promoted in 1864 to lead the entire 47th Regiment) reported that companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left-wing companies (B, E, G, H, and K) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops. In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th engaged in a Divisional Review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” Also around this time, Captain Junker issued his first Special Order:

I. 15 minutes after breakfast every tent will be cleaned. The commander of each tent will be held responsible for it, and every soldier must obey the orders of the tent commander. If not, said commanders will report such men to the orderly Sgt. who will report them to headquarters.

II. There will be company drills every two hours during the day, including regimental drills with knapsacks. No one will be excused except by order of the regimental surgeon. The hours will be fixed by the commander, and as it is not certain therefore, every man must stay in his quarter, being always ready for duty. The roll will be called each time and anyone in camp found not answering will be punished the first time with extra duty. The second with carrying the 75 lb. weights, increased to 95 lb. The talking in ranks is strictly forbidden. The first offense will be punished with carrying 80 lb. weights increased to 95 lbs. for four hours.

In his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed still more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review overseen by Colonel Tilghman Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward for the regiment’s impressive performance that day—and in preparation for the even bigger adventures and honors that were yet to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan ordered his staff to ensure that brand new Springfield rifles were obtained and distributed to every member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Sometime during the month of November or December, Private Joseph Bachman (alternate spelling: “Backman”) suffered a ruptured hernia; he was subsequently discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability on 16 December.

1862

The New Year brought several changes to the regiment, including the departures of First Lieutenant and Regimental Adjutant James W. Fuller, Jr. on 9 January and Private Paul Ferg, a saddler by trade whose hearing was damaged after he fell ill due to exposure from the cold. He was discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability on 20 January.

Next ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862, marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church. Sent by rail to Alexandria, they then sailed the Potomac via the steamship City of Richmond to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped before they were marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C. The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland.

U.S. Naval Academy Barracks and temporary hospital, Annapolis, Maryland, circa 1861-1865 (public domain).

Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

By the afternoon of Monday, 27 January, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had commenced boarding the Oriental. Ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamers, the enlisted men boarded first, followed by the officers. Then, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, the Oriental steamed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. The 47th Pennsylvanians were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the United States, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

* Note: Sometime while stationed at Camp Griffin, Private Andres Snyder became one of several members of the 47th Pennsylvania to be felled by disease; confined to the post hospital for treatment, he was left behind as the regiment moved on. He was subsequently discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability on 3 June 1862.

Company K and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Key West by early February 1862. There, they were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor. During the weekend of Friday, 14 February, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers introduced their presence to Key West residents by parading through the streets of the city. That Sunday, a number of soldiers from the regiment attended to their spiritual needs by sitting in on the services at local churches, where they also met and mingled with residents from the area.

Drilling daily in heavy artillery tactics, they strengthened the fortifications at this federal installation, felled trees and built new roads.

Sometime during this phase of service, several members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers contracted typhoid fever, and were confined to the post hospital at Fort Taylor. Privates Amandus Long, Augustus Schirer (alternate spelling: “Shirer”), George Leonhard (alternate spelling: “Leonard”), and Lewis Dipple of K Company died from “Febris Typhoides” on March 29, 5 April, 19 April, and 27 April 1862, respectively. According to Schmidt:

Pvt. Schirer was buried in grave #6 at the Key West Post Cemetery, but his remains lost their identity enroute [sic] to Fort Barrancas National Cemetery, where he is buried as an unknown in a group of 228….

“And as if this were not enough, Pvt. George Leonard of Company K died in the General Hospital at Key West on Saturday, April 19. He was a miner in civilian life and was another member lost to Typhoid. His remains were originally buried in grave #9 at the Key West Post Cemetery and later removed to Fort Barrancas National Cemetery Section 17, grave 163….

Pvt. Lewis Dipple … former locksmith died in the General Hospital at Key West, and was buried in grave #10 at the Key West Post Cemetery, when the cemetery was abandoned and the bodies moved to Fort Barrancas National Cemetery, his body was one that was mishandled, and his remains are buried in a group of 228 unknown graves.

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina from mid-June through July, they camped near Fort Walker before relocating to the Beaufort District, Department of the South, roughly 35 miles away. Frequently assigned to hazardous picket detail north of their main camp, as Company K was on 5 July, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania were put at increased risk from enemy sniper fire when sent out on these special teams. According to historian Samuel P. Bates, during this phase of their service, the men of the 47th “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing.”

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

On 29 July 1862, drummer Daniel K. Fritz and Private Rudolph Fisher, K Company’s wagoner, were discharged on Surgeons’ Certificates of Disability. According to Schmidt:

Pvt. Fisher would never make it home, as he died in a New York hospital just three weeks later while enroute to Longswamp. The 21 year old Musician Fritz, a laborer from Allentown who had performed in such a lively manner on board ship while the 47th was enroute to Key West, now had failing eyesight and was sick with typhoid fever….

On Tuesday, August 19 [1862], Pvt. Rudolph W. Fisher, a teamster with Company K, who had been discharged with a surgeon’s certificate on July 29, died in the hospital in New York of chronic diarrhea. Pvt. Fisher was 35 years old and a carpenter from Longswamp, Pa. Along with Cpl. Williamson who was discharged and would die at home on August 29, his was another death not available to statistical analysis, since both died as civilians.

Private Rudolph Fisher was subsequently laid to rest at the Alsace Lutheran Church Cemetery in Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania.

Several weeks later, on 20 August, Private Frederick Neussler (alternate spelling: “Nessler”) lost his battle with typhoid and dysentery. According to Schmidt:

The third of the eight men who had been left behind at Key West, died on Tuesday, July 22. Pvt. Martin Muench [sic] of Company K, a 39 year old miner from Allentown was the victim of chronic diarrhea. Pvt. Muench had originally been buried in grave #40 of the Key West Post Cemetery, but when his body was removed in 1927 for relocation to the Fort Barrancas Cemetery, it was mishandled resulting in the loss of identification, and burial in an unknown grave….

Pvt. Frederick Neussler of Company K died at the Key West Hospital on Wednesday, August 20 [1862], from typhoid fever. The 24 year old miner from Hazelton had been left behind with the other hospitalized members of the regiment when it left for Beaufort. The young man’s illness may have been complicated by his reported chronic diarrhea and the yellow fever epidemic which was just beginning at Key West. His remains were originally interred in grave #65 of the Key West Post Cemetery, but their identity was lost when the bodies were removed to Fort Barrancas Cemetery in 1927.

Meanwhile, the remainder of the regiment continued to soldier on. From 20-31 August 1862, Company K resumed picket duty, this time stationed at “Barnwells” (so labeled by Company C Captain J. P. S. Gobin) while other companies from the regiment performed picket duty in the areas around Point Royal Ferry.

But the month of September brought new changes. Sometime during late August, Private Frederick Sackenheimer (alternate spellings: “Sachsenheimer,” “Saxonheimer”) fell while marching double-quick with the regiment. The fall, severe enough to cause a ruptured hernia, resulted in his discharge on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability on 1 September 1862.

That same day (1 September), musician-privates William A. Heckman (a fifer) and Daniel Dachrodt (a drummer whose surname was spelled incorrectly on Bates’ roster as “Dackratt”), were promoted from the rank of Musician to Principal Musician. Dachrodt would go on to serve with his regiment for the duration of the war, and live to become the last surviving member of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band. His final drum beat was struck during a 1939 performance.

* Note: Although a 2011 article about Daniel Dachrodt, which appeared on the Sigal Museum’s website (and which also appeared in Easton, Pennsylvania’s The Express-Times), stating that Daniel Dachrodt served with the Company H of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Dachrodt’s entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives indicates that he served as a member of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band, and re-enlisted in December 1862 with the 47th’s Company K.

On 16 September, Private Patrick McFarland became the next member of K Company to die while in service; he passed away while stationed at Fort Jefferson.

Saint John’s Bluff and the Capture of a Confederate Steamer

During a return expedition to Florida beginning 30 September, the 47th joined with the 1st Connecticut Battery, 7th Connecticut Infantry, and part of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in assaulting Confederate forces at their heavily protected camp at Saint John’s Bluff overlooking the Saint John’s River area. Trekking and skirmishing through roughly 25 miles of dense swampland and forests after disembarking from ships at Mayport Mills on 1 October, the 47th captured artillery and ammunition stores (on 3 October), which had been abandoned by Confederate forces due to the bluff’s bombardment by Union gunboats.

* Note: The capture of Saint John’s Bluff followed a string of U.S. Army and Navy successes which enabled the Union to gain control over key southern towns and transportation hubs. In November 1861, the Union’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron established a base at Port Royal, South Carolina, enabling the Union to mount expeditions to Georgia and Florida. During these forays, U.S. troops took possession of Fort Clinch and Fernandina, Florida (3-4 March 1862), secured the surrender of Fort Marion and Saint Augustine (11 March), and established a Union Navy base at Mayport Mills (mid-March). That summer, Brigadier-General Joseph Finnegan, commanding officer of the Confederate States of America’s Department of Middle and Eastern Florida, placed gun batteries atop Saint John’s Bluff overlooking the Saint John’s River and at Yellow Bluff nearby. Fortified with earthen works, the batteries were created to disable the Union’s naval and ground force operations at and beyond Mayport Mills, and were designed to house up to 18 cannon, including three eight-inch siege howitzers and eight-inch smoothbores and Columbiads (two of each).

After an exchange of fire between U.S. gunboats Uncas and Patroon and the Rebel battery at Saint John’s Bluff on 11 September, Rebel troops returned after initially being driven away. When a second, larger Union gunboat flotilla also failed to shake the Rebels loose again six days later, Union military leaders ordered a more aggressive operation combining ground troops with naval support.

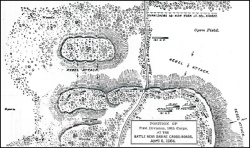

J.H. Schell’s 1862 illustration showing the earthen works which surrounded the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff along the Saint John’s River in Florida (public domain).

Backed by the U.S. gunboats Cimarron, E.B. Hale, Paul Jones, Uncas and Water Witch and their 12-pound boat howitzers, the 1,500-strong Union Army force commanded by Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan advanced up the Saint John’s River and inland along the Pablo and Mt. Pleasant Creeks on 1 October 1862 before disembarking and marching for the battery atop Saint John’s Bluff. The next day, Union gunboats exchanged shellfire with the Rebel battery while the Union ground force continued on. When the 47th Pennsylvanians reached Saint John’s Bluff with their fellow brigade members on 3 October 1862, they found an abandoned battery. (Other Union troops discovered that the Yellow Bluff battery was also Rebel-free.)

With those successes, Union leaders ordered the gunboats and army troops to extend the expedition. As they did, they captured assorted watercraft as they advanced farther up the river.

Companies E and K of the 47th were then led by Captain Yard on a special mission; the men of E and K Companies joined with other Union Army soldiers in the reconnaissance and subsequent capture of Jacksonville, Florida on 5 October 1862.

A day later, sailing up river on board the Union gunboat Darlington (formerly a Confederate steamer)—with protection from the Union gunboat Hale, men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies E and K traveled 200 miles along the Saint John’s River. Another Confederate steamer, the Gov. Milton, was reported to be docked near Hawkinsville, and had been engaged in furnishing troops, ammunition and other supplies to Confederate Army units scattered throughout the region, including the batteries at Saint John’s Bluff and Yellow Bluff.

Identified as a thorn that needed to be plucked from the Union’s side, the Gov. Milton was seized by the soldiers from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies E and K with support from other Union troops. Having ventured deep into Confederate territory, Union Army expedition leaders determined that their troops had achieved enough success for the risks taken, and ordered the combined Union Army-Navy team to sail the Gov. Milton back down the Saint John’s River before moving the steamer and other captured ships behind Union lines.

Integration of the Regiment

Meanwhile, back at its South Carolina base of operations, the 47th Pennsylvania was making history as it became an integrated regiment. On 5 and 15 October 1862, respectively, the regiment added to its muster rolls several young Black men who had endured plantation enslavement in the Beaufort vicinity:

- Just 16 years old at the time of his enlistment, Abraham Jassum joined the 47th Pennsylvania from a recruiting depot on 5 October 1862. Military records indicate that he mustered in as “negro undercook” with Company F at Beaufort, South Carolina. Military records described him as being 5 feet 6 inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, and stated that his occupation prior to enlistment was “Cook.” Records also indicate that he continued to serve with F Company until he mustered out at Charleston, South Carolina on 4 October 1865 when his three-year term of enlistment expired.

- Also signing up as an Under Cook that day at the Beaufort recruiting depot was 33-year-old Bristor Gethers. Although his muster roll entry and entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File in the Pennsylvania State Archives listed him as “Presto Gettes,” his U.S. Civil War Pension Index listing spelled his name as “Bristor Gethers” and his wife’s name as “Rachel Gethers.” This index also includes the aliases of “Presto Garris” and “Bristor Geddes.” He was described on military records as being 5 feet 5 inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, and as having been employed as a fireman. He mustered in as “Negro under cook” with Company F on 5 October 1862, and mustered out at Charleston, South Carolina on 4 October 1865 upon expiration of his three-year term of service. Federal records indicate that he and his wife applied for his Civil War Pension from South Carolina.

- Also attached initially to Company F upon his 15 October 1862 enrollment with the 47th Pennsylvania, 22-year-old Edward Jassum was assigned kitchen duties. Records indicate that he was officially mustered into military service at the rank of Under Cook with the 47th Pennsylvania at Morganza, Louisiana on 22 June 1864, and then transferred to Company H on 11 October 1864. Like Abraham Jassum, Edward Jassum also continued to serve with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers until being honorably discharged on 14 October 1865 upon expiration of his three-year term of service.

More men of color would continue to be added to the 47th Pennsylvania’s rosters in the weeks and years to come.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren (“G. W.”) Alexander, the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined with other Union regiments to engage the heavily protected Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina—including at Frampton’s Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge—a key piece of the South’s railroad infrastructure which Union leaders felt should be destroyed.

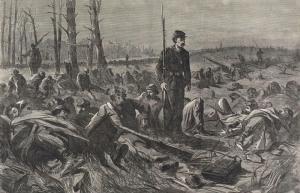

The challenging environment of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad was illustrated by Harper’s Weekly in 1865.

Harried by snipers en route to the Pocotaligo Bridge, they met resistance from yet another entrenched, heavily fortified Confederate battery which opened fire on the Union troops as they entered an open cotton field.

Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests. But the Union soldiers would not give in; grappling with the Confederates where they found them, they pursued the Rebels for four miles as the Confederate Army retreated to the bridge. There, the 47th relieved the 7th Connecticut.

Unfortunately, the enemy was just too well armed. After two hours of intense fighting in an attempt to take the ravine and bridge, the 47th was forced by depleted ammunition supplies to withdraw to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th Pennsylvania were significant. Captain Charles Mickley of G Company died where he fell from a gunshot wound to his head while K Company Private John McConnell was also killed in action.

K Company Captain George Junker was mortally wounded by a minie ball from a Confederate rifle during the intense fighting near the Frampton Plantation, as were Privates Abraham Landes (alternate spelling: “Landis”) and Joseph Louis (alternate spelling: “Lewis”). All three died the next day while being treated for their wounds at the Union Army’s General Hospital at Hilton Head, South Carolina.

Private John Schuchard, who was also mortally wounded at Pocotaligo, died from his wounds at the same hospital on 24 October.

Der Lecha Caunty Patriot‘s 3 December 1862 issue noted the return to Pennsylvania of the remains of 47th Pennsylvanians: Henry A. Blumer, Aaron Fink, Henry Zeppenfeld, and Captain George Junker (public domain).

Although a Find A Grave memorial for Captain Junker currently indicates that he was laid to rest at the Beaufort National Cemetery in Beaufort, South Carolina, the 3 December 1862 edition of Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, a German language newspaper serving the Lehigh Valley region of Pennsylvania during this time, reported that his remains were returned to family in Hazleton, Luzerne County for reburial. Roughly translated, it also noted that Allentown undertaker, Paul Balliet, and several others from the area, had spent 14 days traveling to and from Beaufort to exhume and return the bodies (Körper) of Junker and several other members of the regiment. Privates Abraham Landes, Joseph Louis, and John Schuchard were, however, apparently buried at Beaufort.

Private Gottlieb Fiesel, who had also sustained a head wound, somehow survived. Although the left side of his head had been damaged and his skull fractured by shrapnel from an exploding artillery shell, physicians were hopeful that he might recover since surgeries to remove bone fragments from his brain had been successful, but he contracted meningitis while recuperating and passed away at Hilton Head on 9 November 1862. He, too, was interred at the Beaufort National Cemetery.

Private Edward Frederick lasted a short while longer, finally succumbing on 16 February 1863 at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, Florida to brain fever, a complication from the personal war he had waged with his battle wounds. He was initially buried at the fort’s parade grounds.

Private Jacob Hertzog, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Co. K, successfully recovered from a gunshot wound to his right arm, circa 1866 (U.S. Surgeon General’s Office, public domain).

K Company’s Corporal John Bischoff and Privates Manoah J. Carl, Jacob F. Hertzog, Frederick Knell, Samuel Kunfer, Samuel Reinert, John Schimpf, William Schrank, and Paul Strauss were among those wounded in action who rallied. Private Strauss miraculously survived an artillery shell wound to his right shoulder, recuperated, and continued to serve with the regiment. Private Knell was discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability on 9 May 1863.

Private Hertzog, who had been discharged two months earlier on his own Surgeon’s Certificate, on 24 February 1863, had sustained a gunshot wound (“Vulnus Sclopet”) to his right arm; his treatment, like that of the aforementioned Private Fiesel, was detailed extensively in medical journals during and after his period of service:

[A]dmitted to Hospital. No. 1, Beaufort, S.C., with gunshot wound of right elbow joint, the ball entering the outer, and emerging just above the inner condyle of the humerus of on [sic] the opposite side.

Oct. 26t. Exsection of the lower end of humerus, and articulating ends of the ulna and radius was performed, and the arm laid upon an angular splint of two parallel strips, leaving an open space the whole extent, thus rendering approach to the wound of exit easy. Morph. sulph. was applied to the wound, and a dressing of serate cloth to cover the whole, a bag of ice was also applied.

Nov. 1st. Suppuration considerable, but the great tumefaction of the arm and forearm, much diminished.

Nov. 15th. The sutures of lead wire were to-day removed, the wound having healed sufficiently to keep the parts in shape. The general condition of the patient improved.

Dec. 15th. The patient has been for some days dressed and walking about the grounds. The wound is nearly healed, the elbow admitting of free motion in every direction.

Dec.28th. The wound has been some days healed, there are no discharges, the patient was to-day sent north per steamer ‘Star of the South.’ The good result attained in the above case, may without doubt, be attributed partially to the excellent condition of the patient; he never having used in his life, either alcoholic or malt liquors, neither tea, coffee, nor tobacco.

The command vacancy created when Captain George Junker fell in battle at Pocotaligo was immediately filled when First Lieutenant Charles W. Abbott was advanced to the rank of Captain that same day.

On 23 October, the 47th Pennsylvania returned to Hilton Head, where it served as the funeral Honor Guard for Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South who had succumbed to yellow fever on 30 October. The Mountains of Mitchel, a part of Mars’ South Pole discovered by Mitchel in 1846 while working as a University of Cincinnati astronomer, and Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, were both later named for him. Men from the 47th Pennsylvania were given the high honor of firing the salute over his grave.

On 27 October 1862, First Sergeant Alfred P. Swoyer was honorably discharged from Company K in order to re-enlist as a Second Lieutenant with the same unit and regiment, which he did that same day at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, Florida.

On 1 November 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania helped another Black man escape from slavery near Beaufort when they added 30-year-old Thomas Haywood to the kitchen staff of Company H. Described as a 5 feet 4 inch-tall laborer with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, he was officially mustered in as an Under Cook at Morganza, Louisiana on 22 June 1864, and served until the expiration of his own three-year term of service on 31 October 1865.

1863

Fort Jefferson’s moat and wall, circa 1934, Dry Tortugas, Florida (C.E. Peterson, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, much of 1863 was spent garrisoning federal installations in Florida as part of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps, Department of the South. The men of K Company joined with Companies D, F, and H in garrisoning Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. So remotely situated off the coast of Florida was this Union outpost that it was accessible only by ship.

Meanwhile, Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I continued to guard Key West’s Fort Taylor.

While serving as a Second Lieutenant at Fort Jefferson under Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, Company K’s David K. Fetherolf was promoted to the rank of First Lieutenant on 2 May 1863; he was then appointed Acting Quartermaster at Fort Jefferson in August 1863, and continued in this role through at least December of that year.

As with their previous assignments, the men soon came to realize that disease would be their constant devil, making it all the more remarkable that, during this phase of service, the majority of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers chose to re-enlist when their three-year service terms were up. Many, who could have returned home with their heads legitimately held high after all they had endured, re-enlisted in order to preserve the Union of their beloved nation.

Private Martin Münch (alternate spellings: “Muench,” “Munch”) became one of those men from the 47th Pennsylvania felled by disease during this phase of service; he died from disease-related complications at the Union’s post hospital at Fort Taylor in Key West on 22 July 1863.

As the fall of 1863 arrived, departures from the regiment continued. Private John Koffler was sent home via a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability on 7 September while on 1 October, K Company’s Private Elias Huhn died at the Union Army’s General Hospital at Hilton Head, South Carolina. He was felled by anasarca, a form of edema common to those suffering from malnutrition, heart or kidney disease.

1864

The holidays had been times of both celebration and hardship for members of the 47th Pennsylvania. Stationed far from home, many would mark another year away from friends and family with promotions following their re-enlistment at Fort Taylor or Fort Jefferson. Corporal Matthias Miller was one such man; he advanced to the rank of First Sergeant on New Year’s Day.

Then, in early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858 following the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. Per orders issued earlier in 1864 by Brigadier-General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, that the fort be used to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade, Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of men from Company A were charged with expanding the fort and conducting raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. Graeffe and his men subsequently turned the fort into both their base of operations and a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate Army deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops. According to Schmidt:

Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard. Lt. Harris was directed to tow the Matchless if necessary.

Punta Rassa was probably the location where the troops disembarked, and was located on the tip of the southwest delta of the Caloosahatchee River … near what is now the mainland or eastern end of the Sanibel Causeway… Fort Myers was established further up the Caloosahatchee at a location less vulnerable to storms and hurricanes. In 1864, the Army built a long wharf and a barracks 100 feet long and 50 feet wide at Punta Rassa, and used it as an embarkation point for shipping north as many as 4400 Florida cattle….

Capt. Graeffe and company were disembarked on the evening of January 7, and Gen. Woodbury ordered the company to occupy Fort Myers on the south side of the Caloosahatchee, about 12 miles from its mouth and 150 miles from Key West. Shortly after, [a detachment of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company stationed on Useppa Island] was also ordered to proceed to Fort Myers and join the main body of Company A, the entire command under direct orders of the General who was in the area…. Gen. Woodbury returned to Key West on the Honduras prior to January 19, and the command was left in charge of Capt. Graeffe who dispatched various patrols in search of refugees for enlistment and for activities involving Confederate cattle shipments.

Company A’s muster roll provides the following account of the expedition under command of Capt. Graeffe: ‘The company left Key West Fla Jany 4. 64 enroute to Fort Meyers Coloosahatche River [sic] Fla. were joined by a detachment of the U.S. 2nd Fla Rangers at Punta Rossa Fla took possession of Fort Myers Jan 10. Captured a Rebel Indian Agent and two other men.’

A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documents the time of Richard Graeffe and the men under his Florida command this way:

A small contingent of 20 men and two officers from the Pennsylvania 47th Regiment, led by Captain Henry Crain of the 2nd Regiment of Florida, arrived at the fort on January 7, 1864. A short time later, the party was joined by another small detachment of the 47th under the command of Captain Richard A. Graeffe. Over a short period, increasing reinforcements of the fort led to increasing cattle raids throughout the region. A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans back then and now a neighborhood within the city), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reunited regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

* Note: The Red River Campaign had not even begun for the men of Company K before tragedy struck. According to Henry Wharton:

Just as the steamer was rounding, preparatory to our landing … on the beach … at Algiers, a fatal accident happened to a member of Company K. He was sitting in one of the side hatches of the boat, lost his balance and before a boat could get to him, either from the steamer or shore, he was drowned. No one saw him fall, and it was only known by seeing him come up astern of the boat, that a ‘man was overboard’. His cap was found: on the vizier was ‘F.K.’, by which means it was discovered the missing man was Frederick Koehler, a citizen of Lehigh County and a member of Company K, Capt. Abbott.”

On 1 March, Private David Klotz was transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps (also known as the “invalid corps”). Ten days later, Privates William Brecht, Werner Erbe and John Hinderer were all also transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps while Private John F. Fersch was discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability.

(Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.)

Red River Campaign

From 14-26 March, the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched for Alexandria and Natchitoches, Louisiana, by way of New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington.

From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James and John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were then officially mustered in for duty on 22 June at Morganza. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “(Colored) Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long harsh-climate trek through enemy territory, the men encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Marching until mid-afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians were then rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division. Sixty members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (Mansfield).

The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill. Company K’s Second Lieutenant Alfred P. Swoyer was one of those killed in action at Mansfield.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

Casualties were severe. Privates Nicholas Hagelgans, Jacob Madder and Samuel Wolf of K Company were all killed in action. The regiment’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander, was nearly killed, and the regiment’s two color-bearers, both from Company C, were also seriously wounded while preventing the American flag from falling into enemy hands.

Still others from the 47th were captured by Confederate troops. Held initially as prisoners of war at Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, they were subsequently marched roughly 125 miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as POWs until they were released during prisoner exchanges beginning 22 July. Private Ben Zellner of K Company, who had been shot in the leg and ultimately ended up being wounded in action a total of four times during 1864, was one of the men carted off to Camp Ford.

After some time as a POW in Texas, Private Zellner became one of 300 to 400 men deemed well enough by Camp Ford officials to be shipped to Shreveport, Louisiana. They were then transported by rail to the notorious Confederate POW camp at Andersonville, Georgia. Held there until his release in September 1864, Zellner recovered and continued to serve with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. He was then wounded in action again during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on 19 October 1864.

* Note: Although Camp Ford records (under the surname of “Cellner”) show that Benjamin Zellner was released during a prisoner exchange on 22 July 1864, Ben Zellner stated in multiple newspaper accounts after war’s end that he had been shipped off to Andersonville and held there until his release in September 1864.

While Private Benjamin Zellner was a POW at Andersonville, other members of the 47th Pennsylvania remained imprisoned at Camp Ford in Texas. Sadly, at least two members of the 47th never made it out alive.

Following what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, the 47th Pennsylvanians fell back to Grand Ecore, where they remained for 11 days and engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications. They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April, arriving in Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night, after marching 45 miles. While en route, they were attacked again—this time at the rear of their brigade, but they were able to quickly end the encounter and continue on.

The next morning (23 April 1864), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee’s Confederate Cavalry in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”). Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s 20-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops situated near a bayou and on a bluff, Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending the other two brigades to find a safe spot where his Union troops could ford the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, other Emory troops worked their way across the Cane River, attacked Bee’s flank, forced a Rebel retreat, and erected a series of pontoon bridges, enabling the 47th and other remaining Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners.

In a letter penned from Morganza, Louisiana on 29 May, Henry Wharton described what had happened to the 47th Pennsylvanians during and immediately after making camp at Grand Ecore:

Our sojourn at Grand Ecore was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one on the boys, for by ten o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty-five miles. On that day the rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns, opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebel prisoners say it ‘seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth of this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton of Western Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” for the Union officer who ordered its construction, Lt.-Col. Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, they learned they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned yet again to the hard labor of fortification work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that enabled Union gunboats to more easily make their way back down the Red River. While all of this was going on, K Company’s Private William Walbert was slowly slipping away. On 30 April, he succumbed to disease-related complications at a Union Army hospital in New Orleans.

While stationed in Rapides Parish in late April and early May, according to Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam [Bailey’s Dam] had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits [sic] on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

On Sunday, May 15, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad wherewith the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired and we advanced ‘till dark, when the forces halted for the night, with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

Having entered Avoyelles Parish, they “rested on their arms” for the night, half-dozing without pitching their tents, but with their rifles right beside them. They were now positioned just outside of Marksville, Louisiana on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, the infantry advanced in line until they reached Mousoula [sic], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport on the Achafalaya [sic] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of our army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.*

* Note: Disease continued to be a truly formidable foe, claiming yet more members of the 47th Pennsylvania. On 17 May, Private Josiah Stocker died at the University General Hospital in New Orleans. Private Mathias Gerrett (alternate spelling of surname: “Garrett”) then died from fever at the Union’s Barracks Hospital in New Orleans on 24 May 1864. Sergeant John Gross Helfrich, Solomon Long, Joseph Smith, and T. J. Helm, would also later die on 5 August, 21 August, 2 September, and 21 September, respectively. All six now rest in marked graves at the Chalmette National Cemetery in St. Bernard Parish while Private Charles Resch, who would die at a Union Army hospital in Baton Rouge on 18 August, rests at the Baton Rouge National Cemetery. (Although various historical sources place the death of Private Matthias Gerrett as 22 May 1864 or 30 October 1865 and his cause of death as congestive fever, his entry in the U.S. Army’s Register of Deaths of U.S. Volunteer Soldiers states that he succumbed to typhoid fever at the Union’s Barracks Hospital in New Orleans on 24 May 1864.)

Continuing on, the surviving members of the 47th marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. According to Wharton, the members of Company C were sent on a special mission which took them on an intense 120-mile journey:

Company C, on last Saturday was detailed by the General in command of the Division to take one hundred and eighty-seven prisoners (rebs) to New Orleans. This they done [sic] satisfactorily and returned yesterday to their regiment, ready for duty. While in the City some of the boys made Captain Gobin quite a handsome present, to show their appreciation of him as an officer gentleman.

Wharton also provided the following update regarding Company C, which had rejoined the bulk of the 47th Pennsylvania on 28 May 1864:

The boys are well. James Kennedy who was wounded at Pleasant Hill, died at New Orleans hospital a few days ago. His friends in the company were pleased to learn that Dr. Dodge of Sunbury, now of the U.S. Steamer Octorora, was with him in his last moments, and ministered to his wants. The Doctor was one of the Surgeons from the Navy who volunteered when our wounded was sent to New Orleans.

In June of 1864, Company K lost another of its members when Private Paul Houser died while on furlough; he was among those men who drowned near Cape May, New Jersey during the sinking of the steamer Pocohontas. Follow-up coverage in The New York Times reported that many of the men who lost their lives were on their way home, having been wounded in action or taken ill while in service to their nation.

While encamped at Morganza, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania in Beaufort (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864. The regiment then moved on once again, and arrived in New Orleans in late June.

The Controversy

While these battles, marches, and other military actions were all unfolding, a controversial incident roiled not only the 47th Pennsylvania’s officers’ corps, but senior levels of the Union Army’s leadership in Louisiana.

The 11 May 1864 Evening Star in Washington, D.C. gave a glimpse into the situation with the startling news that Major William H. Gausler and First Lieutenants W. H. R. Hangen and William Reese of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had been dismissed from military service “for cowardice in the actions of Sabine Cross Roads and Pleasant Hill on the 8th and 9th of April, and for having tendered their resignations while under such charges” (AGO Special Order No. 169, 6 May 1864).

The allegations against the 47th Pennsylvania’s officers would continue to trouble the hearts and minds of regimental leaders for months as the situation went unresolved—despite official protests that were lodged by Colonel Tilghman Good and other officers from the 47th who condemned the allegations of cowardice against Gausler, Hangen, and Reese as grossly inaccurate and unfair. The stain was finally removed from the regiment when President Abraham Lincoln stepped in. According to The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, President Lincoln personally reviewed and reversed the Adjutant General’s findings against Gausler. On 14 October 1864, Lincoln wrote to U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton:

Please send the papers of Major Gansler [sic], by the bearer, Mr. Longnecker. A. LINCOLN

An annotation to Lincoln’s collected works explains that “Mr. Longnecker was probably Henry C. Longnecker of Allentown, Pennsylvania,” and makes clear that, although Major W. H. Gausler had indeed been dismissed for cowardice, President Lincoln disagreed with the decision, and overturned it on 17 October 1864. The notation further explains, “Although the name appears as ‘Gansler’ in Special Orders, it is ‘Gausler’ on the roster of the regiment.”

A more detailed explanation of why the 47th Pennsylvania’s field and staff officers were so angered by the allegations against Gausler and the others was later provided in Gausler’s 1914 obituary in The Allentown Leader:

“[Gausler] was court martialed for making a superior officer apologize on his knees at the point of a gun for slurring Pennsylvania German soldiers, but was pardoned by President Lincoln.”

Although the incident left a sour taste in the mouths of the 47th Pennsylvania’s officers, they did not let it deter them from their mission. After arriving in New Orleans, they received orders on the 4th of July to return to the East Coast, and loaded their men onto ships in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I steamed for the Washington, D.C. area beginning 7 July while the men from Companies B, G and K remained behind on detached duty and to await transportation. Led by F Company Captain Henry S. Harte, the 47th Pennsylvanians who had been left behind in Louisiana finally sailed away at the end of the month aboard the Blackstone. Arriving in Virginia on 28 July, they reconnected with the bulk of the regiment at Monocacy, Virginia on 2 August, but they missed the opportunity the earlier departing men had to have a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July 1864, and also missed the mid-July Battle of Cool Spring at Snicker’s Gap, Virginia.

Meanwhile, the Red River Campaign’s most senior leader, Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks, was being removed from command amid the controversy regarding the Union Army’s successes and failures. Placed on leave by President Abraham Lincoln, he later redeemed himself by spending much of his time in Washington, D.C. as a Reconstruction advocate for the people of Louisiana.

On 24 July 1864, Captain J. P. S. Gobin was promoted from his leadership of Company C to the rank of Major and service with the central regimental command of the 47th Pennsylvania.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

On 1 August, K Company received word that their own First Sergeant Matthias Miller would be promoted again, advanced this time to the rank of Second Lieutenant; in addition, Corporal Franklin Beisel became First Sergeant Beisel that same day, and Private Samuel Reinert was promoted to the rank of Corporal.

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in early August, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, Virginia, and also engaged over the next several weeks in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville and other locations within the vicinity (Middletown, Charlestown and Winchester) as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

During this phase of duty, K Company continued to lose members. Among those who were honorably discharged were: Privates Martin Reifinger and Elenois Druckenmiller who departed via Surgeons’ Certificates of Disability on 3 and 18 August, respectively, and Private Conrad Nagel (alternate spellings: “Nagle,” “Neihl,” “Niehl”), who fell ill and was confined to the Union Army’s hospital at Virginia’s Fairfax Seminary near Alexandria, Virginia before succumbing to disease-related complications on 22 August. Private Charles Richter subsequently died at the Union Army’s Newton General Hospital in Baltimore on 1 September. The likely cause of his death was dysentery.

The 47th Pennsylvania then engaged with Confederate troops in the Battle of Berryville, Virginia from 3-4 September. Several men were killed or wounded in action, including Private George Kilmore (alternate spelling “Killmer”), who sustained a fatal gunshot wound to the abdomen on 5 September.

On 14 September, Corporal Elias F. Benner was promoted to the rank of Sergeant.

Other men departing around this time from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were: Company D’s Captain Henry Woodruff, E Company’s Captain Charles H. Yard and Captain Henry S. Harte of F Company, as well as K Company’s Sergeant-Major Conrad Volkenand, Sergeant Peter Reinmiller, Corporals Lewis Benner and George Knuck, and Privates Valentine Amend, M. Bornschier, Charles Fisher, Charles Heiney, Jacob Kentzler, John Koldhoff, Anthony Krause, Elias Leh, Samuel Madder, Lewis Metzger, Alfred Muthard, John Schimpf, John Scholl, and Christopher Ulrich. All mustered out at Berryville, Virginia on 18 September 1864 upon expiration of their respective three-year terms of service. Those members of the 47th who remained on duty were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill