Alternate Spellings of Surname: Graeff, Graeffe, Graeph, Graffee

The life story of Richard A. Graeffe is one of valor, virtue and vision. Courageous enough as a teenager to cross an ocean in search of a better life, he grew to manhood while in service to his adopted homeland, ultimately becoming a leader of men in both times of war and peace while still just in his twenties.

Formative Years

Born in Germany in the community of Aplaleben [possibly Alsleben or Aschersleben?] on 24 October 1833, Richard Graeffe was a son of Ferdinand Graeffe and Caroline (Schmidt) Graeffe, both natives of Germany. According to an application for a U.S. passport completed by him in 1889, he emigrated from Germany to the United States in 1847, and became a naturalized U.S. citizen in 1889—a quarter of a century after he had faithfully and honorably helped to preserve America’s Union.

Mexican-American War

Richard A. Graeffe enlisted for military service almost as soon as he arrived on the shores of the United States of America. As a member of the federal forces engaged in the Mexican-American War from 1847 to 1852, he served with the United States Army as a Corporal with Company E of the 4th Artillery.

After mustering out, he began to make a new life for himself—a journey which would be interrupted in December of 1860 as relations between America’s North and South worsened and the domino effect of states seceding from the Union began.

Civil War Military Service — Three Months’ Service (9th Pennsylvania Infantry)

One of the first men to answer President Abraham Lincoln’s April 1861 call for 75,000 troops to help quell the South’s burgeoning rebellion following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces, Richard A. Graeffe enrolled for military service in Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania. He then mustered in for duty with Company G of the 9th Regiment, Pennsylvania Infantry at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County on 24 April 1861. He served under Lieutenant-Colonel William H. H. Hangen. The men of Company G under Graeffe at this time (who would also later serve in the 47th Pennsylvania in Graeffe’s own company) included: Adolphus Dennig, Martin Eppler, Francis Mittenberger, and John Henry Stein.

Richard A. Graeffe was commissioned as a Captain upon enlistment. From the time of his arrival at Camp Curtin until his regiment’s departure for West Chester on 4 May 1861, Graeffe and his fellow 9th Pennsylvanians were armed, equipped, and drilled daily in infantry tactics.

Stationed next at Camp Wayne in West Chester, Graeffe and his men were joined there by the 11th Pennsylvania Infantry. (More than a few of the soldiers from the 11th Pennsylvania would also later become part of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.)

On 26 May 1861, the members of the 9th Pennsylvania were transported by train to Philadelphia and then on to Wilmington, Delaware, where they remained until 6 June 1861 “to encourage and strengthen the local sentiment, and to prevent the sending of troops to the rebel army,” according to Samuel P. Bates in his History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5.

Joining Major-General Robert Patterson’s command in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania in early June as part of the 4th Brigade, 1st Division headed by U.S. Army Colonel Dixon S. Miles, the men of the 9th Pennsylvania next pitched their tents near Greencastle on 13 June 1864. Three days later, they forded the Potomac River on the right of the 4th Brigade—literally wading chest deep at some points en route to their encampment, which was situated between Williamsport and Martinsburg, Virginia. The next day, they were ordered back across the river where, still part of the 4th Brigade, they were now under the leadership of Brigade Commander, Colonel H. C. Longenecker and Division Commander, Major-General George Cadwalader. Stationed here through the end of the month, they were assigned to picket duty.

Excerpted from Battle of Falling Waters montage (Harper’s Weekly, 27 July 1861). “Council of War” depicts “Generals Williams, Cadwallader, Keim, Nagle, Wynkoop, and Colonels Thomas and Longnecker” conferring on the eve of battle.

Following the Union’s battle with Rebel troops at Falling Waters, Virginia, the men of the 9th Pennsylvania (having not fought in that engagement) were ordered to head for Martinsburg, Virginia, where they remained from 3-15 July when they broke camp and marched toward Bunker Hill. (Although Major-General Patterson had initially planned to have his forces meet the Rebels head on at Bunker Hill and Winchester, officers directly under his command changed his mind during a Council of War on 9 July in Martinsburg. A confrontation there would be disastrous for the Union, they reasoned, because the enemy was not only heavily fortified and entrenched, it could be easily resupplied and bolstered by an infusion of troops brought in via the Confederate-controlled railroad.)

History has proven those officers correct. Having avoided a likely bloodbath, Captain Graeffe and the 9th Pennsylvania encamped with the 4th Brigade near Charlestown from 17-21 July, and then headed for Harper’s Ferry. After crossing the Potomac into Maryland, the 9th made camp roughly a mile away. The next day, not a single casualty among their ranks, Captain Richard A. Graeffe and the 9th Pennsylvanians headed home by way of Hagerstown and Harrisburg. Having completed his Three Months’ Service, Captain Richard Graeffe honorably mustered out with his regiment at Camp Curtin on 29 July 1861.

Civil War Military Service — Three Years’ Service (47th Pennsylvania Volunteers)

With the war not waning, Richard A. Graeffe promptly re-enlisted for a three-year tour. According to A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers , authored by Lewis Schmidt: “The Easton Express reported on August 14 that … 33-year-old Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, a merchant from Easton who would command Company A of the 47th, was recruiting at Glantz’s’ in Easton.”

* Note: Glantz’s was a local saloon owned by Charles Glantz. Appointed 8 November 1858 as Captain of a local militia unit, the Easton Jaegers, Glantz served as a Major with the central regimental staff of the 9th Pennsylvania Infantry, and was one of Richard A. Graeffe’s commanding officers during his Three Months’ Service. Prior to it all, Glantz partnered with Willibald Kuebler to open the Kuebler Brewery in Easton in 1852. The pair stored the lager they manufactured in man-made caves along the bank of the Delaware River.

On 15 August 1861, Richard A. Graeffe re-enrolled for military service at Easton in Northampton County. According to Schmidt, the Easton Rifles then “held an election of officers in Camp Washington at Easton” on 4 September. “Richard A. Graeffe was chosen Captain with his rank effective September 1; a 31-year-old painter, James F. Myers as First Lieutenant; and a 25-year-old machinist, Adolph Dennig as Second Lieutenant…. Capt. Graeffe established his recruiting office at F. Beck’s Saloon on Northampton Street, and he and Lt. Myers were still looking for additional recruits to take to Harrisburg for their company when they returned to Easton on September 12.”

Captain Richard Graeffe then mustered in again on 16 September at Camp Curtin, where he was officially commissioned a Captain with the newly formed 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Military records at the time described him as a merchant residing in Northampton County who was 5’8” tall with auburn hair, brown eyes and a fair complexion.

Having enrolled from early August through 15 September 1861, the ninety-three men that Captain Graeffe had recruited mustered in under him as “Company A” of the 47th Pennsylvania on 16 September.

Following a brief light infantry training period at Camp Curtain, Captain Graeffe and the men of A Company were transported with the 47th Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C., where they were stationed about two miles from the White House at “Camp Kalorama” on Kalorama Heights near Georgetown beginning 21 September. The next day, C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton penned the following update to the Sunbury American newspaper:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

On 24 September 1861, the members of Company A and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers officially mustered in with the U.S. Army. Three days later, on September 27, a rainy, drill-free day which permitted many of the men to read or write letters home, the 47th Pennsylvanians were assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens. By that afternoon, they were on the move again, headed for the Potomac River’s eastern side where, upon arriving at Camp Lyon in Maryland, they were ordered to march double-quick over a chain bridge and off toward Falls Church, Virginia.

Arriving at Camp Advance at dusk, the men pitched their tents in a deep ravine about two miles from the bridge they had just crossed, near a new federal military facility under construction (Fort Ethan Allen), which was also located near the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (nicknamed “Baldy”), the commander of the Union’s massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Armed with Mississippi rifles supplied by the Keystone State, their job was to help defend the nation’s capital.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads after having been ordered with the 3rd Brigade to Camp Griffin. Three weeks later, sometime around noon on Monday, 21 October, “Companies A and B were marched to Gen. Smith’s headquarters where they waited to leave for picket duty again,” according to Schmidt:

Shortly thereafter, Major Gausler [the regiment’s third-in-command] arrived with 15 cavalrymen who accompanied the two companies on a seven-mile march through Lewinsville in the direction of Fairfax Court House. Along the way the men passed many Rebel huts of Spruce and Pine, and made frequent detours off the road to avoid barricades of trees, until a point was reached about 6 miles from Fairfax Court House. Here, 20 men of Company B’s first platoon were detailed as skirmishers along with two cavalry scouts, to move out and advance a mile through the fields and woods. The rest of the men remained in reserve, until the detachment returned without locating anything but chestnuts and a halter strap. The commands of Captains Graeffe and Rhoads returned to camp in time for a supper of ‘speck and crackers’, and a much needed rest at tattoo.

On Friday morning, 22 October, the 47th participated in a Divisional Review, described by Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.”

Just under a month later, on 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review that was overseen by Colonel Tilghman Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Their performance that day was so exemplary that Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan ordered that brand new Springfield rifles be given to each member of the 47th Pennsylvania as a reward for their efforts.

Later that same month, the members of Company A pulled together $2,500 saved from their pay and handed it over to Captain Graeffe, who returned home to Easton, Pennsylvania to deliver the precious funds to the soldiers’ families.

By December, Captain Graeffe had brought Company A’s roster up to a strength of just over a hundred men.

1862

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were transported to Florida aboard the steamship U.S. Oriental in January 1862 (public domain).

Next ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, Captain Graeffe and the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862, marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church. Sent by rail to Alexandria, they then sailed the Potomac via the steamship City of Richmond to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped before they were marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C. The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

By the afternoon of Monday, 27 January 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had commenced boarding the Oriental. Ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamers, Captain Graeffe and his fellow officers were among the last to board. Then, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, the Oriental steamed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. They were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

Alfred Waud’s 1862 sketch of Fort Taylor and Key West, Florida (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

Arriving at Key West in early February 1862, the 47th Pennsylvanians began drilling daily in heavy artillery and other military strategies while protecting Fort Taylor. The regiment also made its presence felt among the locals early on with a parade through the city’s streets on 14 February.

Nine days later, one of Captain Graeffe’s men, Private Andrew R. Bellis, succumbed to complications from a scorpion bite that he had sustained shortly after arrival. The bite, which was being treated by regimental physicians, including the 47th’s Regimental Surgeon Elisha W. Baily, M.D., devolved into Erysipelas, a bacterial skin infection of the upper dermis which often attacks the lymphatic system. (Also known as “St. Anthony’s fire,” the disease generally attacks those with compromised immune systems. Complications, historically, have included abscess, embolism, gangrene, meningitis, pneumonia, and sepsis.) As a result, Private Bellis suffered greatly until drawing his last breath at the 47th’s regimental hospital at Fort Taylor 23 February 1862. He was then laid to rest at the post cemetery in grave number 26.

According to Schmidt, “The company under command of Capt. Graeffe held military services, and the area was draped with red and white decorations and many flower wreaths.” (In 1927, the remains of Private Bellis were exhumed and relocated to the Fort Barrancas National Cemetery (Section 17, grave number 97.)

But there were lighter moments as well. According to a letter penned by Henry Wharton on 27 February 1862, the regiment commemorated the birthday of former U.S. President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation (first delivered in 1796), the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February. The festivities resumed two days later when the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards.” This was then followed by a concert by the Regimental Band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

In early March, Captain Graeffe received orders from his superiors to select a member of his company to report to the post hospital to assist the medical staff. Graeffe selected Private John J. Jones for the task. (Private Jones would last just five months in the role, and would end up being discharged honorably on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability on 12 August 1862.)

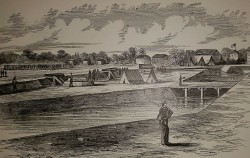

Fort Walker, Hilton Head, South Carolina, circa 1861 (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, public domain).

From mid-June through July, the 47th Pennsylvania was ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina where the men made camp near Fort Wallker before being housed in the U.S. Department of the South’s Beaufort District. Picket duties north of the 3rd Brigade’s main staging area were commonly rotated among the various regiments stationed there during this time, putting individual soldiers at risk from sniper fire. Per historian Samuel Bates, the men of the 47th “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing.”

Around this same time, detachments from the regiment were assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

The men were then sent on a return expedition to Florida. Company A participated with the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff from 1 to 3 October. Led by Brigadier-General Brannan, the 1,500-plus Union force disembarked at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek from troop carriers guarded by Union gunboats.

Taking point, the 47th led the brigade through 25 miles of dense, pine forested swamps populated with snakes and alligators. When it was all over, the brigade had forced the Confederates to abandon an artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, and had paved the way for the Union to occupy the town of Jacksonville, Florida.

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th engaged Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point, the men of the 47th were placed on point once again, but they and their fellow 3rd Brigaders were less fortunate this time.

Picked off by snipers while on the move toward the Pocotaligo Bridge, they also faced dogged resistance from a heavily entrenched and fortified Confederate battery that opened fire on the Union troops as they entered and crossed a clearing. Those headed for the higher ground of the Frampton Plantation fared no better as artillery and infantry fire burst forth from the midst of the surrounding forests.

Bravely, the Union regiments grappled with the Confederates where they found them, pursuing them for four miles as the enemy retreated to the bridge where the 47th then relieved the 7th Connecticut. But the Confederates were just too well fortified. After two hours of intense fighting in an unsuccessful attempt to take the ravine and bridge, sorely depleted ammunition supplies forced the 47th’s withdrawal to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th were significant. Two officers and 18 enlisted men died; two officers and another 114 enlisted were wounded. Several of the resting places for men from the 47th still remain unidentified, the information lost to sloppy Army and hospital records management or the trauma-impaired memories of soldiers who were forced to hastily bury or leave behind the bodies of comrades upon receiving orders to retreat to safer ground.

The 47th Pennsylvania returned to Hilton Head on 23 October, where it served as the funeral Honor Guard for General Ormsby M. Mitchel, the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South, who had succumbed to yellow fever on 30 October. The Mountains of Mitchel, a region of the South Pole on Mars discovered by Mitchel in 1846, and Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, were both later named for him. The men of the 47th Pennsylvania were the soldiers given the high honor of firing the salute over his grave.

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

1863

By 1863, Captain Richard A. Graeffe and the men of A Company were again based with the 47th Pennsylvania in Florida. Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November of 1862, much of 1863 was spent guarding federal installations in Florida as part of the 10th Corps, Department of the South. Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I garrisoned Fort Taylor in Key West while Companies D, F, H, and K garrisoned Fort Jefferson in Florida’s remote Dry Tortugas.

The time spent in Florida by the men of Company A and their fellow Union soldiers was notable not just for these reasons—but for their commitment to preserving the Union. Many of the 47th Pennsylvanians who could have returned home, their heads held high upon expiration of their terms of service, chose instead to re-enlist in order to finish the fight.

1864

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers next turned their attention to Fort Myers, which had been abandoned in 1858 after the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. In early 1864, General D. P. Woodbury, Commander of the U.S. Army’s Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, ordered that this installation be reclaimed and revitalized in order to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade and provide food and shelter for those fleeing Confederate forces—escaped slaves, Confederate Army deserters and pro-Union residents. According to Schmidt:

Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard. Lt. Harris was directed to tow the Matchless if necessary.

Punta Rassa was probably the location where the troops disembarked, and was located on the tip of the southwest delta of the Caloosahatchee River … near what is now the mainland or eastern end of the Sanibel Causeway… Fort Myers was established further up the Caloosahatchee at a location less vulnerable to storms and hurricanes. In 1864, the Army built a long wharf and a barracks 100 feet long and 50 feet wide at Punta Rassa, and used it as an embarkation point for shipping north as many as 4400 Florida cattle….

Capt. Graeffe and company were disembarked on the evening of January 7, and Gen. Woodbury ordered the company to occupy Fort Myers on the south side of the Caloosahatchee, about 12 miles from its mouth and 150 miles from Key West. Shortly after, [a detachment of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company stationed on Useppa Island] was also ordered to proceed to Fort Myers and join the main body of Company A, the entire command under direct orders of the General who was in the area…. Gen. Woodbury returned to Key West on the Honduras prior to January 19, and the command was left in charge of Capt. Graeffe who dispatched various patrols in search of refugees for enlistment and for activities involving Confederate cattle shipments.

Company A’s muster roll provides the following account of the expedition under command of Capt. Graeffe: ‘The company left Key West Fla Jany 4. 64 enroute to Fort Meyers Coloosahatche River [sic] Fla. were joined by a detachment of the U.S. 2nd Fla Rangers at Punta Rossa Fla took possession of Fort Myers Jan 10. Captured a Rebel Indian Agent and two other men.’

Schmidt notes that Graeffe’s hand drawings show there were roughly 12 buildings “primarily situated along the river, with a log palisade protecting those portions not bounded by the Caloosahatchee; the whole in a densely wooded area and entered through an opening on the southeast protected by the river on the west near the area of the wharf, and a log blockhouse on the east.”

An 1856 survey of the fort contained in the Federal Register “suggest that the fort’s wooden stockade ran from just east of Broadway to just east of Royal Palm, and from Main Street on the south to the river bank, which meandered along what is Bay Street today,” according to Tom Hall, creator of a website about the arts in Southwest Florida:

It consisted of as many as three dozen hewn pine buildings which included officers’ quarters … barracks, administration offices, a 2½-story hospital with plastered rooms, warehouses for the storage of munitions and general supplies, a guard house … blacksmith’s and carpenter’s shops, a kitchen, bakery, laundry, a sutler’s store, stables for horses and mules, a gardener’s shack, and even a bowling alley and bathing pier and pavilion.

It also boasted a pier nearly 700 feet long that had wide dock and rails that enabled the soldiers to bring in supplies by tram without having to lighter them ashore. The buildings were sided and topped by cedar shingles shipped in from Pensacola and Apalachicola, together with doors, windows and flooring. The interior featured parade grounds, a carefully-tended velvety lawn, two immense vegetable gardens, rock-rimmed river banks, shell walks, lush palms and even citrus trees.

Also according to Hall:

By the time Captain Richard A. Graeffe and his soldiers arrived at the fort, most of the wood stockade had disappeared, so he ordered his men to construct an earthen wall 15 feet wide by 7 feet tall. Three guard towers were also constructed: one where the hospital had been; a second by the garden and bowling alley; and the third between the stables and riverside warehouse. Then Captain Graeffe sent his troops across the river to begin rounding up the herds of scrub cows being raised by ranchers between Punta Gorda and Tampa. As they did, resistance began to grow. Captain Graeffe realized he needed reinforcements and Companies D and I of the [U.S. Colored Troop’s] 2nd Regiment were brought up from Fort Zachary Taylor in Key West.

A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documents Captain Graeffe’s time in Florida this way:

A small contingent of 20 men and two officers from the Pennsylvania 47th Regiment, led by Captain Henry Crain of the 2nd Regiment of Florida, arrived at the fort on January 7, 1864. A short time later, the party was joined by another small detachment of the 47th under the command of Captain Richard A. Graeffe. Over a short period, increasing reinforcements of the fort led to increasing cattle raids throughout the region. A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.

Captain Richard A. Graeffe, Company A, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, circa 1864 (courtesy of David Sloan).

Early on, according to Schmidt, Captain Graeffe sent the following report to Woodbury:

“At my arrival hier [sic] I divided my forces in three detachment, viz one at the Hospital one into the old guardhouse and one into the Comissary [sic] building, the Florida Rangers I quartered into one of the old Company quarters, I set all parties to work after placing the proper pickets and guards at the Hospital i have build [sic] and now nearly finished a two story loghouse of hewn and square logs 12 inches through seventeen by twenty-two fifteen feet high with a cupola onto the roof of six feet high and at right angle with two lines of picket fences seven feet high. i shall throw up a half a bastion around it as soon as completed. around the old guardhouse i have thrown up a bastion seven feet through at the foot and three feet on the top nine feet high from the bottom of the ditch and five on the inside. I also build [sic] a loghouse sixteen by eighteen of two storys [sic] Southeast of the Commissary building with a bastion around it at right angles with a picket fence each bastion has the distance you recomandet [sic] from the loghouses 20 feet on the sides and 20 to the salient angle, i caused to be dug a well close to bl. houses and inside of the bastions at each Station inside they are all comfortable fitted up with stationary bunks for the men without interfering with the defence [sic] of the work outside of the Bastions and inside the picket fense i have erected small kitchens and messrooms for each station, i am building now a guardhouse build [sic] of square hewn logs sixteen by sixteen two storys high the lower room to be used for the guard and the upper one as a prison, the building to be used for defence [sic] (in case of attack) by the Rangers each work is within view and supporting distance from the other; Capt. Crane with a detachment of his men repaired the wharf, which is in good condition now and fit for use, the bakehouse i got repaired, and the fourth day hier [sic] we had already very good fresh bread; the parade ground is in a good condition had all the weeds mowed off being to [sic] green to burn. i intend to fit up a schoolroom and church as soon as possible.”

Muster rolls for Company A from this period noted that “a detachment of 25 men crossed over to the north west side of the river” on 16 January and “scoured the country till up to Fort Thompson a distance of 50 miles,” where they “encountered a Rebel Picket who retreated after exchanging shots.” Making their way back, they swam across the river, and reached the fort on 23 January. Meanwhile, while that group was still away, Captain Graeffe ordered a smaller detachment of eight men to head out on 17 January in search of cattle. Finding only a few, they instead took possession of four barrels of Confederate turpentine, which were later disposed of by other Union troops.

Graeffe’s men also captured three Confederate sympathizers at the fort, including a blockade runner and spy named Griffin and an Indian interpreter and agent named Lewis. Charged with multiple offenses against the United States, they were transported to Key West, where they were kept under guard by the Provost Marshal—Major William Gausler, third-in-command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

This phase of duty lasted until sometime in February of 1864. The detachment of the 47th which served under Graeffe at Fort Myers is labeled as the Florida Rangers in several publications, including The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, prepared by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert N. Scott, et. al. (1891). Several of Graeffe’s hand drawn sketches of Fort Myers were published in 2000 in Images of America: Fort Myers by Gregg Tuner and Stan Mulford.

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had already left on the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reconstituted regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.

But they had missed the two bloodiest combat engagements that the 47th Pennsylvania would endure during the Red River Campaign—the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield on 8 April and the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April. According to Schmidt, Company A was soon ordered to return the Confederate prisoners to New Orleans, and officially ended their detached duty on 27 April when they rejoined the main regiment’s encampment at Alexandria.

This means that the men from Company A also missed a third combat engagement—the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry”), which took place on 23 April.

From late April through mid-May 1864, the fully reassembled 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and their fellow brigade members helped to build “Bailey’s Dam” near Alexandria, enabling federal gunboats to successfully navigate the fluctuating water levels of the Red River.

Beginning 13 May, the members of Company A moved with the majority of the 47th from Simmesport, across the Atchafalaya, and on to Morganza, before reaching New Orleans on 20 June. On Independence Day, they received orders to return to the East Coast for further duty.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Still able and willing to fight after their time in Bayou country, the soldiers of Company A and the men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies C, D, E, F, H, and I steamed aboard the McClellan beginning 7 July 1864.

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, they joined up with General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July 1864. There, they fought in the Battle of Cool Spring and, once again, assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah from August through November of 1864, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Records of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers confirm that the regiment was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, Virginia in early August 1864, and engaged in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville and other locations within the vicinity (Middletown, Charlestown and Winchester) as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in the Battle of Berryville, and engaged in related post-battle skirmishes with the enemy over subsequent days.

Departing Under a Cloud of Controversy

Although muster rolls for the 47th Pennsylvania documented that Captain Richard A. Graeffe mustered out on 18 September 1864 at Berryville, Virginia upon expiration of his three-year term of service, his entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives states that he mustered out on 10 December 1864. The reason for this confusion is that Captain Graeffe and his colleague Captain Charles Hickman Yard, Sr. left their respective unit commands under a cloud of controversy. According to historian Lewis Schmidt:

“Now a civilian, Captain Yard had a private reception at Carlisle, Pa. on Friday [23 September 1864] as a Court Martial was held and he was charged under Orders #380, dated December 19, 1864. The charges had to do with bounties paid by various communities to the men who re-enlisted and were credited to their draft quotas. The communities involved were Lower Nazareth and Allen Townships in Lehigh County, the Borough of Bethlehem and Eldred Township in Monroe County, and involved bounties of $291, $315, $315 and $310 respectively. It was charged that Captain Yard withheld portions of the bounties for his own use, ranging from $10 to $45 per man for the 70 men involved. He pleaded not guilty, but was found guilty of the specifications and the charge of “Conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman’, and was sentenced to be dismissed from the service. The findings of the court were disapproved by the Secretary of War and the Captain was released from arrest and honorably discharged. Although Captains Yard and Graeffe were each equally charged in the specifications at this court martial involving the Borough of Bethlehem and Eldred Township, Capt. Graeffe would be tried separately on October 17, 1864 with the same results. Those charges at that time would involve both Captains and two additional communities, the Borough of Nazareth and Forks Township in Lehigh County.

* Note: Richard Graeffe’s U.S. Civil War Pension Index Card indicates that, in addition to his service with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, he had also served with Company E of the 4th U.S. Artillery (regular Army).

Return to Civilian Life

After learning of the court’s findings, Richard Graeffe remained briefly in Pennsylvania before heading west in 1868 in search of a better future. Settling in Michigan, he resided in Wayne County for the remainder of his life. The 1870 federal census, which spelled his surname as “Graffee,” documented his life as a farmer and resident of Nankin Township. Jacob Schaub, a 30-year-old native of Holland, resided with him and worked for him as a farm laborer.

Sometime in early 1875, Richard Graeffe traveled to his native Germany. A ship’s passenger manifest for the Westphalia, dated 28 April 1875, listed him as a Detroit resident returning from Hamburg, Germany to New York City.

Just over six months later, on 23 November 1875, the now 41-year-old farmer wed 34-year-old Mary Swartz in Detroit, Wayne County, Michigan. Pastor Charles Haas performed the ceremony witnessed by Martin Burck and Julius W. Parish of Detroit. A daughter of John and Catherine Swartz, Graeffe’s new bride was a Detroit native who had been born sometime around 1836.

By 1880, Richard and Mary Graeffe were shown on the federal census as residents of Detroit. Their surname spelled as “Graeph,” his occupation was still listed as farmer, and his place of birth and that of his parents noted family ties to “Prussia.” Mary was shown on this census as a Michigan native, her mother as a native Pennsylvanian, and her father as having been born in Austria. “Mary Read,” a 19-year-old native New Yorker, was also residing with and working as a servant for the Graeffes in 1880.

Richard Graeffe’s 1889 passport application confirms that he had officially become an American citizen before the decade was over—naturalized on 11 March 1889 in Detroit, Michigan by the Circuit Court of Wayne County. This record also confirms that he had been living “uninterruptedly” since 1868 in Detroit, that he was 5 feet, 8 inches tall with brown eyes, a “proportionate” nose and mouth, round chin, healthy complexion, and a high forehead, and that he was by this time employed as a chemist.

His life would change again before the turn of the century when, on 9 January 1896, he was widowed by Mary. After her death, he continued to make his home in Detroit. By 1900, 39-year-old “Mary Leed” was residing with and working for him as a servant.

Nearly two decades after his wife’s passing, Richard A. Graeffe closed his eyes for the final time. According to his death certificate, he was a retired Army Officer. Claimed by heart failure at Harper Hospital in Detroit on 3 September 1913, he was laid to rest at the Elmwood Cemetery in Wayne County on 6 September 1913.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

2. Civil War Muster Rolls and Related Records (Record Group 19, Series 19.11). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs.

3. Civil War Veterans’ Card File. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

4. Death Certificate (Richard Graeffe), Death Index Listing (Mary S. Graeffe), and Marriage Record (Richard Graeffe and Mary Swartz). Detroit, Michigan: State of Michigan, Department of Vital Statistics.

5. Hall, Tom. Fort Myers: An Alternative History, and Clayton, on the website Arts SWFL.com. Estero.

6. “History Pours from the Lehigh Valley’s Breweries.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 14 March 2015.

7. “Minutes of Council of War Held July 9, 1861, at Martinsburg, Virginia—Captain Simpson, Topographical Engineers,” excerpted in Bates’ History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

8. Returns from U.S. Military Posts, in Records of the U.S. Adjutant General’s Office and Fort Taylor, Key West, Florida (Record Group 84, Microfilm M617). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, March 1863–December 1863.

9. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

10. “Tamiami Trail Modifications: Next Steps—Draft Environmental Impact Statement,” Appendix E. U.S. National Park Service – Everglades National Park: 29 January 2010.

11. U.S. Census (1870, 1880, 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

12. U.S. Civil War Pension Index (Application No.: 877962, Certificate No.: 687955, filed from Michigan by veteran, 4 September 1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

13. U.S. Passport Application (application date: 11 March 1889; passport issued: 14 March 1889). Washington, D.C. and Wayne County, Michigan, 1889 (via U.S. National Archives and Records Administration).

14. U.S. Veterans’ Schedule (1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.