Alternate Names: James Todd, James K. Todd, James K.P. Todd

Born in Potterstown, Hunterdon County, New Jersey on 4 August 1845, James Knox Polk Todd was the son of New Jersey natives, James M. Todd (1813-1897) and Elizabeth M. (Sutton) Todd (1815-1876).

In 1850, he resided in Tewkesbury, Hunterdon County with his parents and siblings: Mary (age 13), Jacob (age 11), Emily (age 9), Hannah (age 3), and Sarah. His father was employed as a constable during this time.

By 1860, James was living in Bushkill Township, Northampton County, Pennsylvania with his parents and New Jersey-born siblings: Margaret (age 24), Mary, Jacob, Emma (age 19), Anna (age 12), Sarah, and Jason (age 7). Their father supported the family as a pedlar while Margaret and Jacob helped out as a seamstress and clerk, respectively.

Civil War Military Service

James K. P. Todd entered Civil War military service as a Private with Company D of the 27th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers on 19 June 1863, but mustered out just a short time later on 1 August 1863.

He then enlisted a second time—as a Private with Company E of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers. Enrolling at Easton, Pennsylvania on 17 December 1863, he mustered in for duty the following day at Philadelphia, and joined up with his regiment from a recruiting depot on 3 January 1864.

During his tenure with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, he fought in two historic Civil War campaigns: Union General Nathaniel Banks’ Red River Campaign (March-May, 1864) and Union General Philip Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, and was also an eyewitness to history when the 47th was assigned to protect the nation’s capital following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln in April 1865.

Military Life

The regiment Private James K. P. Todd was about to join—the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry—had developed a reputation for excellence and dedication to duty in the years before he enlisted. Having been ordered back to Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida on 15 November 1862, following the Union Army’s capture of Saint John’s Bluff (1-3 October 1862) and the intense, bloody Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina (21-23 October 1862), the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had spent much of 1863 fortifying federal installations in Florida as part of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps, Department of the South. The men of E Company had joined with Companies A, B, C, G, and I in guarding Key West’s Fort Taylor while Companies D, F, H, and K garrisoned Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the coast of Florida.

On 25 February 1864, Private James K. P. Todd and the 47th set off for a phase of service in which the regiment would make history. Steaming from Florida for New Orleans aboard the Charles Thomas, the men arrived at Algiers, Louisiana on 28 February and were then shipped by train to Brashear City. Following another steamer rid —this time to Franklin via the Bayou Teche—the 47th joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps. In short order, the 47th would become the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign across Louisiana, which was spearheaded by Union General Nathaniel P. Banks.

From 14-26 March, the 47th trekked through New Iberia, Vermillionville, Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches. Often short on food and water, the members of the regiment encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before moving on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, 60 members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the back-and-forth volley of fire unleashed by both sides during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

Casualties were severe. The regiment’s second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel G. W. Alexander, was nearly killed, and two regimental color-bearers, both from Company C, were also seriously wounded while preventing the American flag from falling into enemy hands. A number of men from Company E were killed or severely wounded in action; some died of their wounds; some died of disease while recuperating from their wounds; still others simply died from yellow fever, typhoid, consumption, dysentery, or one of the the diseases which plagued the regiment during this time.

In addition, a number of men were captured by Confederate forces, marched 125 miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as POWs until released during prisoner exchanges in July, August or November. At least one member of the regiment never made it out Camp Ford alive.

Following what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, the 47th fell back to Grand Ecore, where they resupplied and regrouped until 22 April.

Known as “Bailey’s Dam” for the Union officer who ordered its construction, Lt. Col. Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River in Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 was designed to facilitate passage of Union gunboats to and from the Mississippi River. Photo: Public domain.

On 23 April, the 47th and their fellow brigade members re-engaged with the enemy during the Battle of Cane River at Monett’s Ferry and, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, helped to build a dam from 30 April through 10 May, which enabled federal gunboats to successfully traverse the rapids of the Red River.

Beginning 16 May, Captain Charles Yard and E Company moved with the majority of the 47th from Simmesport across the Atchafalaya to Morganza, and then to New Orleans on 20 June.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Still able and willing to fight after their Bayou battles, the soldiers of Company E and their fellow members of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies A, C, D, F, H, and I returned to the Washington, D.C. area aboard the McClellan beginning 7 July 1864.

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln, they joined Major-General David Hunter’s forces in the fighting at Snicker’s Gap, and assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August, early and mid-September saw the departure of several 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who had served honorably, including Company D’s Captain Henry Woodruff and E Company’s Captain Charles H. Yard. Both mustered out at Berryville, Virginia on 18 September 1864 upon expiration of their respective three-year terms of service. Those members of the 47th who remained on duty were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill, September 1864

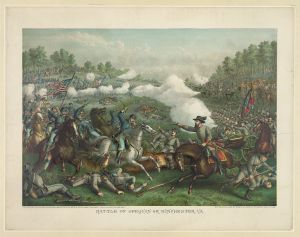

Together with other regiments under the command of Union General Philip H. (“Little Phil”) Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company E and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”). The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces. Kurz & Allison, circa 1893. Public domain, courtesy of the Library of Congress.

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. Advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. Finally reaching and fording the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with Early’s Confederate Army. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and the 19th Corps were directed by General William Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as another Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops trying to cross a clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice—once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

The 19th Corps, with the 47th in the thick of the fighting, then began pushing the Confederates back. Early’s “grays” retreated in the face of the valor displayed by Sheridan’s “blue jackets.” Leaving 2,500 wounded behind, the Rebels retreated to Fisher’s Hill, eight miles south of Winchester (21-22 September), and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union men which outnumbered Early’s three to one. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek.

Moving forward, the surviving members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but they would do so without two more of their respected commanders: Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Good’s second, Lieutenant-Colonel George Alexander, who mustered out 23-24 September upon the expiration of their respective terms of service. Fortunately, they were replaced with leaders who were equally respected for their front line experience and temperament, including Major John Peter Shindel Gobin, formerly of the 47th’s Company C, who had been promoted up through the regimental staff to the rank of Major (and who would be promoted again on 4 November to the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and regimental commanding officer).

Battle of Cedar Creek, October 1864

During the Fall of 1864, General Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents—civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally and win the day.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles—all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he rode rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

The Union’s counterattack punched Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

Once again, casualties were high. Multiple officers and enlisted men from the 47th Pennsylvania were cut down on the battlefields of the Shenandoah Valley. Many were killed outright or died soon after from their wounds; a number survived only to be sent home on Surgeons’ Certificates of Disability; and still others were captured by Confederate forces and spirited away to prison camps in Andersonville, Georgia and Salisbury, North Carolina. A number of these POWs died while still in enemy hands; at least one survived only to die at home as a direct result of what had happened to him at the camp.

Following these major engagements, the 47th was ordered to Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December. Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th was then ordered to outpost and railroad guarding duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia. Five days before Christmas they trudged through a snowstorm in order to reach their new home.

1865 – 1866

Assigned in February to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah, the men of the 47th moved, via Winchester and Kernstown, back to Washington, D.C.

Matthew Brady’s photograph of spectators massing for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, at the side of the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

On 19 April 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were once again responsible for helping to defend the nation’s capital—this time following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Encamped near Fort Stevens, they received new uniforms and were resupplied.

Letters home and later newspaper interviews with survivors of the 47th Pennsylvania indicate that at least one 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while others may have guarded the Lincoln assassination conspirators during their imprisonment and trial. As part of Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania also participated in the Union’s Grand Review on 23-24 May. Captain Levi Stuber of Company I also advanced to the rank of Major with the regiment’s central staff during this time.

Charleston, South Carolina as seen from Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

On their final southern tour, Company E and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians served in Savannah, Georgia from 31 May to 4 June. Again in Dwight’s Division, this time they were with the 3rd Brigade, U.S. Department of the South. Taking over for the 165th New York Volunteers in July, they quartered in Charleston, South Carolina at the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury.

Finally, beginning on Christmas day of that year, the majority of the men of Company E, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers began to honorably muster out at Charleston, South Carolina, a process which continued through early January. Private James K. P. Todd was one of those who mustered out with his regiment on 25 December 1865.

Following a stormy voyage home, the 47th Pennsylvania disembarked in New York City. The weary men were then transported to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader on 9 January 1866, the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were officially given their discharge papers.

After the War

Returning life after his honorable discharge, James K. P. Todd began life anew. In 1873, he wed Pennsylvania native, Mary Jane Mellon (October 1853-May 1928), daughter of Sophia (Steuber) Mellon.

Together, James and Mary Jane Todd made a life in South Easton and the Borough of Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, where they welcomed 14 children to the world. (By 1900, only nine of those children were still alive.)

In 1880, James Todd was employed by a local liquor store and resided in South Easton with his wife and daughters Georgia (age 4) and Ada (age 3, shown as “Addie”), son Jason (age 2), and a two-month-old daughter who was identified on the census as “Fame” (born in April 1880).

The 1890 U.S. Veterans Schedule confirms that James K. P. Todd was living in the Borough of Easton by 1890, and that his military discharge paperwork had been mislaid.

By 1900, almost all of the surviving Pennsylvania-born Todd children (eight of the nine) were still living at home with James and Mary Jane: Ada G. (born in June 1877), Jason B. (11 December 1878-June 1967), Nellie N. (April 1881-February 1969, later married to John Heller), Mary T. (born August 1884), Jacob Harrison Todd (26 April 1887-24 December 1927), James Madison (15 February 1890-1 May 1966), Elizabeth M. (29 May 1893-June 1991), and Florence (born August 1894). Somehow, James K.P. Todd was managing to support his large family on the wages he earned as a day laborer. Ada helped out by working as a servant for another family while Jason and Nellie worked at a shoe factory.

By 1910, James Todd was still working as a laborer, performing odd jobs. Sons, Jacob and James, and daughter, Elizabeth, were working as spinners at an area silk mill. Daughter, Mary, was also working outside of the home. Ada, Jason, and Nellie are no longer shown as living at home at this time.

Less than a decade later, the old soldier was gone. James K.P. Todd passed away in Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania on 27 April 1918. His obituary in the 30 April 1918 edition of the Allentown Democrat failed to fully portray the service he had rendered to his nation, only simply stating that:

James K. Todd, a veteran of the Civil War, died at his home, 1028 Elm St., Easton, aged 73. Besides his wife he is survived by the following children: Jacob H., James M., and Jason Todd, Mrs. Elmer Smull, Miss Elizabeth Todd, of Easton; Mrs. Roscoe Bougher, of the South Side, and Mrs. John Heller, of Slatington, two sisters, Mrs. Sallie Lerch, of Phillipsburg, and Mrs. Annie Beidleman, of Boston. Mr. Todd was a member of the Lafayette Post, No. 217, G.A.R. He served four years and six months in the Civil war. He went to Easton from New Germansville, N.J. many years ago.

One of those who helped to preserve America’s Union and had been a witness to history during one of its most turbulent times, James Knox Polk Todd was laid to rest in Section W, Lot 67 at the Easton Cemetery.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

2. Obituary: James J. Todd. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Allentown Democrat, 30 April 1918.

3. Pennsylvania Veteran’s Burial Index Card (James K. Todd). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans Affairs.

4. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

5. U.S. Census (1850, 1860, 1880, 1900, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

6. U.S. Civil War Pension Index (application no.: 1155837, certificate no.: 1044057, filed from Pennsylvania by the veteran, “James K.P. Todd” on 2 January 1894; application no.: 1120962, certificate no.: 869,130, filed from Pennsylvania by the veteran’s widow, “Mary J. Todd,” on 24 May 1918).

7. U.S. Veterans Schedule (Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania, 1890). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.