At the conclusion of part one of this biographical sketch of Sergeant-Major William McCullough Hendricks, the third year of the U.S. Civil War was winding down, but the sergeant and many of his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians had opted to reenlist to continue the fight to preserve America’s Union.

Back home in Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, his brother Jacob S. Hendricks were among the men who “Paid the Commutation Money” to be exempted from the draft.

1864 — New Adventures at Home and Far Away

As the new year dawned at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida Sergeant-Major Hendricks’ father, Benjamin Hendricks, had begun a brickmaking business back home in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, according to the 9 January 1864 edition of the Sunbury American. The new business employed “steam power and machinery, so that persons desirous of building can always be promptly and abundantly supplied with excellent brick, at reasonable prices.”

* Note: This new business venture of Benjamin Hendricks ultimately succeeded. The 12 August 1865 edition of the Sunbury American reported that family patriarch Benjamin Hendricks had recently begun a brickmaking business, and had agreed to provide “the brick for the new Court House except the pressed brick which comes from Philadelphia.”

Benjamin Hendricks was then reelected once again to the Borough Council on 19 February. The “entire Union ticket” was retained that year with the exception of one individual who no longer wanted to be an office holder, according to the newspaper’s 27 February edition.

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were helping to expand the Union’s reach across the Deep South.

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to send part of its regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858 following the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. Per orders issued earlier in 1864 by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, that the fort be used to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade, Colonel Tilghman Good, in consultation with his superiors, assigned Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of men from Company A to special duty, and charged them with expanding the fort and conducting raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. Graeffe and his men subsequently turned the fort into both their base of operations and a shelter for pro-Union supporters, men and women escaping slavery, Confederate Army deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops. According to Schmidt:

Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard. Lt. Harris was directed to tow the Matchless if necessary….

Capt. Graeffe and company were disembarked on the evening of January 7, and Gen. Woodbury ordered the company to occupy Fort Myers on the south side of the Caloosahatchee, about 12 miles from its mouth and 150 miles from Key West. Shortly after, [a detachment of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company stationed on Useppa Island] was also ordered to proceed to Fort Myers and join the main body of Company A, the entire command under direct orders of the General who was in the area…. Gen. Woodbury returned to Key West on the Honduras prior to January 19, and the command was left in charge of Capt. Graeffe who dispatched various patrols in search of refugees for enlistment and for activities involving Confederate cattle shipments.

During this phase of duty, which lasted until sometime in February of 1864, Graeffe’s A Company men subsequently added more structures and fortifications. They also captured three Confederate sympathizers at the fort, including a blockade runner and spy named Griffin and an Indian interpreter and agent named Lewis. Charged with multiple offenses against the United States, they were transported to Key West, where they were kept under guard by the Provost Marshal—Major William Gausler, third-in-command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documents the time of Richard Graeffe and the men under his Florida command this way:

A small contingent of 20 men and two officers from the Pennsylvania 47th Regiment, led by Captain Henry Crain of the 2nd Regiment of Florida, arrived at the fort on January 7, 1864. A short time later, the party was joined by another small detachment of the 47th under the command of Captain Richard A. Graeffe. Over a short period, increasing reinforcements of the fort led to increasing cattle raids throughout the region. A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.

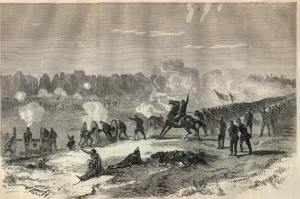

Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield, Louisiana, 8 April 1864 (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 14 May 1864, public domain).

While all of that was unfolding, Colonel Good, Sergeant-Major William Hendricks, and the other members of the 47th’s officers’ corps had begun preparing to take the members of all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.)

Red River Campaign

Upon the arrival in Louisiana of the second group of companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, the now almost fully reunited regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

From 14-26 March, the 47th marched for the top of the L in the L-shaped state, passing through New Iberia, Vermilionville, Opelousas, and Washington en route to Alexandria.

On 8 April, they engaged in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield). Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, 60 members of the 47th were cut down during the volley of fire. The fighting waned only when darkness fell. Exhausted, the uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded.

After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill. C Company’s Private Jeremiah Haas was one of the many killed that day; Private Thomas Lothard was one of the even larger number wounded.

Early the next morning, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were up and moving again. Ordered into a vital defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spread up onto a high bluff. By mid-day, they were fending off a charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States)—brutal fighting which was still raging at 3 p.m.

Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the 47th Pennsylvanians were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

During this engagement, the 47th Pennsylvania also recaptured a Massachusetts artillery battery that had been lost during the earlier Confederate assault. Unfortunately, while he was mounting the 47th Pennsylvania’s colors on one of the recaptured Massachusetts caissons, Color-Sergeant Benjamin Walls was shot in the left shoulder. As Walls fell, Sergeant William Pyers was then also shot while preventing the American flag from falling into enemy hands. The regiment also nearly lost its second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel G. W. Alexander, who was severely wounded in both legs during what has come to be known today as the Battle of Pleasant Hill.

All three ultimately survived their wounds, but many others, including several members of C Company, were killed or wounded in action—or captured by Confederate troops and marched roughly 125 miles to Camp Ford, the largest Confederate prison camp west of the Mississippi, which operated near Tyler, Texas. Although most of the POWs from the 47th Pennsylvania were released during a series of prisoner exchanges from July through November, at least two members of the 47th died while in captivity while still others remain missing to this day.

Following what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, the 47th Pennsylvanians fell back to Grand Ecore, where they remained for 11 days and engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications.

While stationed at Grand Ecore, the 47th Pennsylvanians received the shocking news that Major William S. Gausler had been discharged for cowardice on 11 April 1864. The charges proved unfounded, however, and were reversed personally in October by President Abraham Lincoln, who allowed the major to resign with his rank intact. On 15 April 1864, C Company First Lieutenant William Reese was also similarly charged and dismissed. Although he was forced to wait nearly a year for those charges to be overturned, his honor was also restored when the dismissal was revoked by the U.S. War Department and Office of the Adjutant General on 18 February 1865.

At this same time, others in the regiment were being honored for their bravery, including Second Lieutenant Daniel Oyster who was promoted to the rank of First Lieutenant on 16 April 1864.

Beginning on 22 April, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers moved back to Natchitoches Parish, arriving in Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night, after marching 45 miles. While en route, they were attacked again—this time at the rear of their brigade, but they were able to quickly end the encounter and continue on.

The next morning (23 April 1864), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee’s Confederate Cavalry in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”). Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s 20-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops situated near a bayou and on a bluff, Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending the other two brigades to find a safe spot where his Union troops could ford the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, other Emory troops worked their way across the Cane River, attacked Bee’s flank, forced a Rebel retreat, and erected a series of pontoon bridges, enabling the 47th and other remaining Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. Encamping overnight before resuming their march toward Rapides Parish, the 47th Pennsylvanians finally arrived on 26 April in Alexandria, where they camped for 17 more days (through 13 May 1864).

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” for Lt.-Col. Joseph Bailey, the officer overseeing its construction, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River in Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

During this phase of duty, the 47th Pennsylvania was placed under the temporary command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey from 30 April to 10 May, and assigned to help build a timber dam across the Red River to enable Union gunboats to more easily negotiate the river’s fluctuating water levels. Following the completion of Bailey’s Dam, they then headed back toward the southern part of the state, marching toward Simmesport and then Morganza, Louisiana beginning May 13.

In a new letter penned roughly two weeks later (which ran in the 18 June 1864 edition of the Sunbury American), Henry Wharton reported that:

Company C, on last Saturday [21 May 1864] was detailed by the General in command of the Division to take one hundred and eighty-seven prisoners (rebs) to New Orleans. This they done satisfactorily and returned yesterday [28 May 1864] to their regiment, ready for duty. While in the City some of the boys made Captain Gobin quite a handsome present, to show their appreciation of him as an officer gentleman. The boys are well.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers then continued on with their march, finally reaching New Orleans on 20 June. It was here on the 4th of July that Wharton, Hendricks and their fellow C Company soldiers learned that their fight was still far from over.

An Encounter with Lincoln and Snicker’s Gap

Beginning 7 July 1864, Sergeant-Major William Hendricks and the men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I steamed for the East Coast aboard the McClellan. Upon their arrival in Virginia, they had a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, and then joined up with Major-General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July 1864. There, they fought in the Battle of Cool Spring and, once again, assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

On 24 July, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin was promoted from leadership of the C Company to the central regimental command staff at the rank of Major.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Attached to the Middle Military Division, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah from August through November of 1864, it was at this time and place, under the leadership of legendary Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, that the members of the 47th Pennsylvania would engage in their greatest moments of valor. Of the experience, Company C Drummer Boy Samuel Pyers said it was “our hardest engagement.”

On 1 September 1864, First Lieutenant Daniel Oyster and Sergeant-Major William M. Hendricks were both promoted—Oyster to the rank of Captain and Hendricks to the rank of First Lieutenant. Four days later, Captain Oyster was wounded at Berryville, Virginia. On 7 September 1864, Henry D. Wharton provided the following report from the 47th Pennsylvania’s encampment near Berryville:

For several days after the army had advanced up this valley, the men were busily engaged in building intrenchments [sic] and fortifying their position, two miles west of Charlestown. During the entire night and the whole next day were the boys at work with the shovel and pick, carrying rails, &c., building breastworks for the protection of the regiment, and scarcely was the job finished, the bright spade put aside, when ‘fall in’ was heard, and the 47th was moved to another place to build other earthworks. – This they done [sic] cheerfully, knowing the work was necessary; and that it was for their own protection. The position held by our army, at that point, was excellent, and so well arranged was [sic] our defences, that an attack made on us by the enemy would have been disastrous to him, and added another list to the name of Union victories. The enemy knew this, and after finding out Sheridan’s strength fell back towards Winchester, keeping his head quarters [sic] at Bunker Hill. Our forces on last Saturday morning, then broke up camp, following them to within one mile of this place, where we found signs of the Johnnies. The 8th corps, Gen. Crooks, commanding, was, in the advance who rested in line of battle, with arms stacked, for a couple of hours, while pickets were being posted. After the pickets had been established this command went into camp, and had just finished pitching their tents, which was about four o’clock P.M., when heavy skirmishing was heard on the picket line. The whole command was rapidly turned out and formed, and moved to the support of the pickets, who had been driven from behind some intrenchments [sic], which they had occupied.

From the correspondent of the Baltimore American, I learn the following facts of the fight:

The 36th Ohio and 9th Virginia were formed, and charged the enemy, driving then out of the entrenchments. A desperate struggle now ensued, the rebels being determined, if possible, to regain possession of these entrenchments. With this object in view they massed full two divisions of their command and hurled them with their accustomed ferocity against our gallant little band, who were supported by both Thoburn’s and Duvall’s division. They were handsomely repulsed every time they changed, the conflict lasting long after the sun had sent, and artillery firing being kept up until 9 o’clock.

Our loss was about three hundred killed and wounded that of the enemy, from good information, was at least one-third greater, besides fifty prisoners and a stand of colors.

While the fight was going on, the 6th and 19th corps were pushed forward and took up several lines, but not being needed, did not share in the punishment given the rebels. On the next day, Sabbata [sic], the pickets had hard work and done a great deal of firing with the enemy. A member of Company C., to which I belong, told me he fired fifty-three rounds at them. What punishment was inflicted I cannot tell you, on the part of the Johnies sic], but to our men, I know it was small; two men of the 47th wounded by the same ball, and they slightly.

On Monday the 47th was out on a reconnoisance [sic]. Four companies were in advance as skirmishers, who soon were received by a shower of bullets from the graybacks. This did not, in the least deter them, for they gave as good as they got, and with the regiment pushed on driving the enemy before them. The main portion of the regiment dare not fire, for if they did, the shooting of our own men who have been the consequence, so they stood the whizzing of bullets about their ears, as well as could be expected, under the circumstances. In this work two members of Co., C., were wounded. David Sloan, flesh wound in right arm from a minnie ball, and Benjamin McKillips in right hand. These wounds are slight, but at the present time somewhat painful, not so much so, however, as to prevent them enjoying that great luxury of a soldier – sleep. Capt. Oyster was struck by a ball, staggering him, but otherwise doing no injury. In his being hit there is a circumstance connected, that I cannot help but giving you, even you may put it down as a fish story, though for the truth the whole company will vouch. The ball struck him on the back of his shoulder, made a hole in his vest and shirt and none in the coat. Two members of Co. K., were wounded – one of them has since died.

The whole army have [sic] been busily engaged in digging intrenchments [sic], and throwing up breastworks, and now occupy a very strong position. Whether there will be an engagement here, or what the movements are to be, I can form no opinion, for if there was a General ever kept his thoughts, Sheridan is the one, and it is an impossibility to find out anything until it is completed. For material to write on, one is continued to his own Brigade, and there is so much sameness in that, that it would be but a repetition to send it to you. If I were to take down the ‘thousand and one’ rumors that daily come into camp, I could fill columns of the American, weekly, but as I prefer facts, I hope you will be satisfied if I send you news semi-occasionally.

I wrote to you a few days ago of the promotions in Company C, but for fear they did not reach you, I send them again: Daniel Oyster, Captain; William M. Hendricks, 1st Lieutenant; and Christian S. Beard, 2nd Lieutenant. They are well liked, and in their new positions give satisfaction. With the exception of the wounded, the boys are well, perfectly contented with their lot, only that they have a great hankering for the greenbacks that is [sic] due to them.

Color-Bearer Benjamin Walls, the oldest member of the entire regiment, was mustered out upon expiration of his three-year term of service on 18 September—despite his request that he be allowed to continue his service to the nation.

Opequan and Fisher’s Hill

“…reports of artillery shook the earth and the air seemed filled with the whiz of shells and bullets, commingled with the cheers of men engaged in deadly strife….” – Henry D. Wharton, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Inflicting heavy casualties during the Battle of Opequan (also known as “Third Winchester”) on 19 September 1864, Sheridan’s gallant blue jackets forced a stunning retreat of Jubal Early’s grays—first to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September) and then, following a successful early morning flanking attack, to Waynesboro.

These impressive Union victories helped Abraham Lincoln secure his second term as President but, once again, there were casualties.

On 23-24 September Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander mustered out upon expiration of their respective terms of service. The 47th Pennsylvanians would remain in good hands, however, as John Peter Shindel Gobin continued his advancement up the chain of command.

Cedar Creek

Sheridan rallying his troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

On 19 October 1864, Early’s Confederate forces briefly stunned the Union Army, launching a surprise attack at Cedar Creek, but Major-General Sheridan was able to rally his Union troops. Intense fighting raged for hours and ranged over a broad swath of Virginia farmland. Weakened by hunger wrought by the Union’s earlier destruction of crops, Early’s troops gradually peeled off, one by one, to forage for food while Sheridan’s forces fought on, and won the day.

But it was another extremely costly engagement for Pennsylvania’s native sons. The 47th suffered a total of 176 casualties during the Cedar Creek encounter alone, including: Sunbury Guards’ Sergeant John Bartlow and Privates James Brown (a carpenter), Jasper B. Gardner (a conductor), George W. Keiser (an 18-year-old farmer), Theodore Kiehl, Joseph Smith, and John E. Will—all killed in action on 19 October. Sergeant William Pyers, father of Company C Field Musician Samuel H. Pyers and the very same gallant Sunbury Guarsdsman wounded while protecting the colors at Pleasant Hill, also departed from the field of battle forever at Cedar Creek.

Corporal William F. Finck and Privates George P. Blain, Perry Colvin, Jesse Green, George D. John, Isaac Kramer, William Michael, Richard O’Rourke, Henry A. Shiffin, John Sunker, Joseph Walters, and David Weikle were all wounded, as was Captain Daniel Oyster, who sustained another gunshot wound—this time to his other shoulder.

Still others were captured and held as POWs at the most notorious of the prison camps operated by the Confederate States of America—Andersonville (Georgia), Libby (Virginia), and Salisbury (North Carolina). A number of 47th Pennsylvanians never returned, including Private Martin M. Berger, who reportedly died on 6 January 1865 in a hole he had dug at Salisbury to protect himself from the elements.

As First Lieutenant William M. Hendricks and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers mourned their dead and missing while recuperating at their encampment near Cedar Creek, more men were recognized for their valor. On 1 November 1864, C Company Corporal Samuel Y. Haupt was promoted to the rank of Sergeant. Three days later, Major John Peter Shindel Gobin, former Captain of Company C, was again promoted up the ranks of the regimental command structure—this time to Lieutenant-Colonel.

In his letter of 14 November 1864 from the 47th Pennsylvania’s encampment near Newtown, Virginia, Henry Wharton reported the following:

The day after election the entire army of the Shenandoah left their old camps at Cedar creek and fell back to this place. The reason of this was the scouts reported a force coming down the Luray Valley and the removal enabled General Sheridan to get a better position and establish lines unknown to the enemy. Intrenchments [sic] have been, and are now being constructed that will baffle the ingeniousness of the best rebel Generals, and such, that behind them our forces can repel double their numbers, and if they have the temerity to make an attack, with the number not slain or crippled by our arms, few could escape being captured. – Such is the position we now occupy.

For the last three days a considerable number of the enemy’s cavalry have been bothering our pickets, with the purpose, no doubt, of finding out our position. Our Brigade, (the 2d) was sent out to give the Johnnies a chance for a fight, but on their arrival, the cavalry of Jefferson D. fell back out of range of our rifles. Since then our cavalry went out in several directions for the purpose of giving them fight or gobble them up, the latter if possible. Brigadier General Powell took the road to Front Royal, met the graybacks, whipped them, captured one hundred and sixty prisoners, two pieces of artillery, (all they had) their caissons, ammunition, ambulances, wagon train, and drove the balance ten miles from where they first met. Of the other cavalry we have had no report as yet, but from the fact that they are led by a man who knows not defeat, the daring General Custer, we can expect news that will cheer the hearts of all who are in favor of putting down the rebellion by force of arms.

The election passed off quietly and without any military interference, not the influence of officers used in controlling any man’s vote. In the regiments from the old Keystone, the companies were formed by the first Sergeant, when he stated to the men the object for which they were called to ‘fail to,’ and then they proceeded to the election of officers to hold the election – the boys having the whole control, none of the officers interfering in the least.

The resulting vote totals from the 47th, according to Wharton, were as follows: Company A (10 for Lincoln, 1 for McClellan), Company B (26 for Lincoln, 2 for McClellan), Company C (29 for Lincoln, 15 for McClellan), Company D (31 for Lincoln, 11 for McClellan), Company E (24 for Lincoln, 3 for McClellan), Company F (18 for Lincoln, 16 for McClellan), Company G (9 for Lincoln, 13 for McClellan), Company H (10 for Lincoln, 24 for McClellan), Company I (19 for Lincoln, 16 for McClellan), and Company K (18 for Lincoln, 19 for McClellan) with totals of 194 for Lincoln and 121 for McClellan.

The 47th was claimed for McClellan, and at Harrisburg we were ranked as Copperheads; in fact two officers, mustered out of service by reason of expiration, boasted in their speeches on the stump at home, that their old regiment was strongly in favor of the hero of the gunboat, Galena. Our vote has proven that they were slightly mistaken, not to use stronger language. The battle at Cedar Creek thinned our ranks by which we lost many votes – this number and those away in hospitals would have increased the Union majority to three hundred.

Col. T. H. Good has resigned and left us for home. Before leaving he issued the following address:

‘Soldiers of the 47th,’ – More than three years ago I assumed command as your Colonel. My relations with you as your commander have been of the most pleasing character. Your fidelity, zeal, soldierly conduct and military bearing worthy of my most hearty commendation, and to leave you, after so long a term, I trust, of mutual confidence, is indeed a painful duty. When the most of you re-enlisted under the call of the President for veterans, it was my intention to have remained with you, and leave now, only, by reason of distasteful Brigade associations. My sense of honor will not permit me to remain longer with an organization in which I have suffered nothing but indignities since our connection with its [sic] as a regiment.

I would gladly have taken each of you by the hand and personally assured you of my confidence of your patriotism, my high appreciation of your military knowledge and to have thanked you for your uniform good conduct and respectful obedience, had not my overpowered feelings told me I was unequal to the task. I take this method, therefore, of bidding the living of the 47th, farewell, and at the same time sympathize with you in your loss of beloved officers and comrades, although dead, they are happy in victory.

Trusting that the rebellion will be speedily suppressed, the authority of the Government re-established, peace re-visit our land each of you be permitted to enjoy the pleasures of home and the smiles of those near and dear. I bid you, and all, a soldier’s farewell.

Col. Good was a most excellent officer and was beloved by the officers and men of his regiment. Although his loss is regretted by all, the boys are most pleased with his successor, Lieut. Col. J. P. Shindel Gobin. This resignation will soon place the Lieut. Colonel in full command of the regiment. I have been informed he has already been commissioned by Gov. Curtin. Promotions come so fast on our old Captain that the boys forget his title and scarcely know how to address him. That those of his company are well pleased you may be assured, for they know his true worth, and are certain if bravery an daring on the field of battle deserves an honor, the shoulders of their late Captain should be graced with the Eagle.

Lieut. Hendricks has just received notice of the death of a member of Co. C., Jacob C. Grubb. Another victim of the battle of Cedar Creek.

Stationed at Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December, more men died from their combat wounds and lost battles with disease—and more men were promoted. Then, five days before Christmas, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered to march again—this time through a snowstorm for outpost duty at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia.

1865

Receiving his final promotion in January 1865, John Peter Shindel Gobin was now a Colonel. But all was not well with the regiment and its extended family. In its 15 February 1865 edition, the Sunbury American reported the following disturbing news:

MEAN THIEVES. – We learn that the house of Lieut. Wm. Hendricks, in the southern part of this borough, was robbed last week of a number of valuable articles. This, we consider, is contemptibly low, and the individual who commits an act on this kind on the family of a soldier who is absent in the army, should meet with scorn and contempt from every man, woman and child. If he would reflect for a moment, he will see that he has become a doggedly low thief, and is a little the meanest of the mean thieves who are prowling about in this place.

Two days later, William Hendricks’ father was reelected yet again to the Sunbury Borough Council, according to that day’s edition of the newspaper. On 20 February 1865, William’s brother, Sam, enrolled for Civil War military service at Harrisburg in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, and mustered in as a Second Lieutenant with the 74th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers.

* Note: Promoted to the rank of First Lieutenant on 29 March, Sam Hendricks served until 12 May of that same year when he was discharged by Special Order No. 224, which was issued by the U.S. War Department and Office of the Adjutant General.

Matthew Brady’s photograph of spectators massing for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, at the side of the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Assigned first to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah in February, the men of the 47th were ordered back to Washington, D.C. 19 April to defend the nation’s capital again—this time following President Lincoln’s assassination.

Sunbury Guardsman Samuel H. Pyers was one of those given the high honor of protecting the late President’s funeral train, assigned to guard duty from Washington, D.C. to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad’s Relay House in Maryland.

On 9 May 1865, First Lieutenant William M. Hendricks resigned his commission, and headed back home to Sunbury in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. Sometime in 1865 or early 1866, he and his wife welcomed the arrival of another daughter—Emma L. Hendricks (circa 1865-1949).

Life Goes On

By 1866, William M. Hendricks had joined forces with his old 47th Pennsylvania comrade John Weiser Bucher and other former Civil War soldiers from Sunbury to form the “Boys in Blue.” According to the 25 August edition of the Sunbury American:

A meeting of the Boys in Blue was held in the old Court House, on Tuesday evening last. The Club now numbers nearly one hundred men, and is daily adding new members to its ranks. The “Boys” have adopted the name of the “Sunbury Club of the Boys in Blue,” and hold regular meetings on every Tuesday evening, at 8 o’clock, to which the public are respectfully invited to attend. At the last meeting the following permanent officers were elected:–

President – Col. W. M. McClure.

Vice Presidents – Sergt. J. H. Love, Lieut. Wm. Hendricks.

Recording Secretary – Capt. J. E. Torrington.

Corresponding Secretary – Lieut. A. N. Brice.

Treasurer – Jno. W. Bucher.

Blue Hill overlooking the Susquehanna River opposite Sunbury, Pennsylvania, circa 1905 (public domain).

In 1867, the 23 February edition of the Sunbury American reported that William Hendricks was elected to the post of Inspector for the Borough of Sunbury. Running on the Union ticket, he was swept into office with his fellow Union candidates in the annual elections in which “[a]n unusual interest was manifested” with “over four hundred votes being polled, the largest number ever cast at a Borough election in this place.” Hendricks beat challenger Robert Farnsworth (237 votes to 165). That same year, William Hendricks’ father served as the borough’s Treasurer, and was also appointed to the Borough Council’s Graveyard and Pavements and Sidewalks Standing Committees.

Also that same year, William Hendricks and his wife welcomed the birth of another daughter—Anna M. Hendricks. Before the decade was out, they were also greeting daughter Eva (in 1869). By 1870, William Hendricks was supporting his family as a clerk in a law office in Sunbury, where he continued to reside with his wife Elizabeth and their children.

Tragically though, in 1872, William Hendricks’ younger sister, Catharine Young Hendricks lost her battle with consumption (tuberculosis), and passed away in Sunbury on 21 May. The Sunbury American reported that she was just 21 years, 4 months and 26 days old at the time of her passing. She was laid to rest at the Pomfret Manor Cemetery.

In mid-August of that same year, the newspaper reported that William Hendricks had assisted in the transport of men convicted of engaging in a riot which rocked the neighboring community of Shamokin on 26 May 1872:

COURT PROCEEDINGS

[Reported by A. N. Brice]

SUNBURY, August 15, 1872The following is a portion of the criminal proceedings of the Quarter Sessions of last week:

Com. vs. Patrick Hester, Michael Gallagher, and others. – Riot. True bill. This is a case of considerable importance, and for the Commonwealth were employed District Attorney, Gen. Clement, J. W. Comley, Wm. Lawson and W. H. Oram, Esqs., and for the Defendants Messrs. Boyer, Simpson, Lavell, Davis and Reimensnyder. The alleged riot occurred in Shamokin, on Sunday, the 26th of May, last. A member of the Molly McGuires [sic] , or of the Ancient Order of Hibernia, as they are now called, died at Locust Gap. Let it be remembered that the Catholic Church, by their rites and laws, forbid the burial of any one [sic] outside the pale of their church in their graveyard, nor will they allow any one [sic] belonging to a secret organization to be buried in their burying grounds. Father Koch, the pastor of St. Edward’s Catholic Church, of Shamokin, on the aforesaid Sunday morning told his congregation that he was told that a member of the Molly McGuires [sic] was about to be forcibly buried in their graveyard, and that it was contrary to their rites, and he further warned his people from going to the ground for fear of a riot. But, after service he said he would go himself and warn them not to go in. He did go, and after he arrived at the graveyard gate, the Molly McGuires [sic] with the body came up. They did not heed him, but broke open the gate, forcibly entered, and forcibly buried the dead body in the graveyard. They carried out their object, and to all intents and purposes, it was carried out in a riotous manner. Pat. Hester, one Kelly and Michael Gallagher tore open the gate, and they marched in, notwithstanding the protest of Father Koch, who had, and how has, by the rites of his church, the sole control of their burying ground. The presence of the pastor of St. Edward’s on that Sunday morning, prevented one of the greatest riots, perhaps, which ever occurred in the coal region. He counselled peace and quiet, and remonstrated kindly, but while he kept the crowd at bay, they still entered the ground. Their entry, and the forcible way it was done, was as much a riot, perhaps, as if it had been done in seas of blood. In this case several priests were present, and the Bishop of Harrisburg, and a large number of very respectable people (catholics and protestants) from Shamokin, were in attendance.

Gallagher above named was tried about a year ago, in our Court, for the murder of the Douty House porter, (colored), and acquitted by the defendant’s friends swearing an alibi. Hester was also tried for the murder of Rey about two years ago in Columbia county, and acquitted in the same way. Both of these men were considered guilty of murder, and, it is said, that Hester has since admitted his guilt.

On Saturday morning the reasons which the defendant’s counsel had filed for a new trial, were overruled by the Court, and the prisoners were brought in and sentenced. The sentences were as follows, in the Eastern Penitentiary: Patrick Smith, two years, Michael Gallagher, two years and three months, and Patrick Hester, two years and seven months. Thus have three bad men been sent out of the community which they have for years overawed and defied, and now receive a just portion of the merits of their crimes which they so richly deserve. It may be true that the bad reputation of these men had not a little to do with their conviction of the crime of riot for which they were tried, but the jury after being out several hours brought in a verdict of guilty of aggravated riot, of conspiracy to riot, and of common riot. The charge of Judge Rockefeller was considered by all, and especially the defendant’s counsel, to be very fair and impartial. The bad character of the men only aggravated their crimes. Their counsel were vigalent [sic] and faithful.

On Saturday morning the Sheriff started to Philadelphia, assisted by Wm. M. Hendricks, John Haag, William Waldron, Wellington Hummel, J. F. Kirby and Martin Gass with the ten convicted candidates for the Eastern Penitentiary and the House of Refuge. The prisoners are as follows:

Wm. Horn, for breaking jail, one year.

Pat Smith, for riot, two years.

Michael Gallagher, for riot, two years and three months.

Pat Hester, for riot, two years and seven months.

John Devany, for riot, three years.

Henry Welker, for riot, one year.

Wm. Delbough, for riot, one year.

John Day, for larceny, one year.

Alex. Rineir, larceny, one year.

James Carter, a colored boy from Milton, for larceny, to the house of refuge….

William M. Hendricks performed a similar function in 1873 when he assisted with the transport of five additional prisoners to the penitentiary, according to the newspaper’s 15 August edition.

The following year—1874—also proved to be a noteworthy one for the Hendricks clan as William M. Hendricks was appointed to the Board of Directors of the Danville Iron Company and as Justice of the Peace for the Borough of Sunbury. In addition, his brother, Sam, and father had also sought elective offices, and were chosen to serve their community, respectively, as Street Commissioner and as member of the Borough Council. The elections were described by the Sunbury American as “the most spirited we have seen in years.”

The election had been a close one for William Hendricks, having defeated James Beard by just 14 votes (159 to 145), but he was unable to savor the victory or even perform his duties as Justice of the Peace for long. Per the 2 July 1875 edition of the Sunbury American:

James Beard, Esq., has received a commission from the Governor for Justice of the Peace of the East Ward, this borough, in place of Wm. M. Hendricks, Esq., deceased.

Funeral and burial records confirm that William McCullough Hendricks had, in fact, died suddenly on 11 June 1875 in Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania. He had not even reached the age of 40 when he was laid to rest at Sunbury’s Pomfret Manor Cemetery.

In response to the devastating news about his old friend, former regimental scribe Henry D. Wharton, penned the following tribute on behalf of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. It was published in the 18 June 1875 edition of the Sunbury American:

In Memorium.

At a meeting of surviving members of Company C, 47th Regiment Pa. Vet. Vols., and other soldiers in the late war, residing in Sunbury, held at the hall of Engine Co., No. 1, on Sunday afternoon, called together by the sad announcement of the death of Lieut. Wm. M. Hendricks, formerly of Company C, 47th Regt. Pa. V., Lieut. A. N. Brice was called to the chair, and H.D. Wharton appointed secretary.

The following resolutions offered by H. D. Wharton, were unanimously adopted:

WHEREAS, When death has closed the earthly career of a comrade, companion and friend, it is a melancholy though not ungrateful duty to give utterance to our grief and recall the virtues which justify it; therefore

Resolved, That the death of Lieut. Wm. M. Hendricks, formerly of Company C, 47th Regiment Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, has filled our hearts with pain, and penetrated us with a sincere and profound sorrow, which will not be repressed, yet can be only feebly expressed.

Resolved, That Lieut. Wm. M. Hendricks was a brave soldier, a faithful officer, a serviceable and valued citizen, a sincere friend and cherished companion, he was patriotic in the true sense of that expressive word; as a son, a husband and a father, and in his intercourse with society, as a citizen, he was upright and just; discharging all the various duties devolved upon him by these several relations with integrity and scrupulous and intelligent fidelity.

Resolved, That we, so recently his comrades in arms, unfeignedly deplore his early death; we mourn not for him, but for ourselves; we are bereaved, but he has been promoted from his temporary camp of instruction to the grand army of the redeemed; our loss is great, but out consolation is in the precious hope of the Christian’s faith.

Resolved, That we condole with his stricken and afflicted family in this their profound sorrow; the loss they mourn we feel; to them his love and presence were strength and joy; to us his companionship was dear, and his memory is cherished in our hearts.

Resolved, That we will attend his funeral as a body, and will wear the appropriate badge of mourning for thirty days.

Resolved, That a committee of three be appointed to convey a copy of these proceedings to the family of our deceased comrade, and that the newspapers of the borough be respectfully requested to publish them.

William McCullough Hendricks was survived by a large family, including his parents, siblings, wife, and children. Learn more about their lives after his death in “What Happened to William Hendricks’ Family?”

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

2. Bell, Herbert Charles, ed. History of Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, Including Its Aboriginal History; the Colonial and Revolutionary Periods; Early Settlement and Subsequent Growth; Political Organization; Agricultural, Mining, and Manufacturing Interests; Internal Improvements; Religious, Educational, Social, and Military History; Sketches of Its Boroughs, Villages, and Townships; Portraits and Biographies of Pioneers and Representative Citizens, etc., etc. Chicago, Illinois: Brown, Runk & Co., Publishers, 1891.

3. Emma Hendricks, in “Elderly Resident of County Seat Expires.” Shamokin, Pennsylvania: Shamokin News Dispatch, 23 September 1949.

4. Hendricks Family, in Genealogical and Biographical Annals of Northumberland County Pennsylvania, Containing a Genealogical Record of Representative Families, Including Many of the Early Settlers, and Biographical Sketches of Prominent Citizens, Prepared from Data Obtained from Original Sources of Information. Chicago, Illinois: J. L. Floyd & Co., 1911.

5. Hendricks Family Birth Records (Benjamin Hendricks), in Pennsylvania Births and Christenings, 1709-1950 (Rows or Salem Lutheran Church, Penn Township, Snyder County, Pennsylvania, FHL microfilm 924,005). Salt Lake City, Family History Library, 26 September 1811.

6. Hendricks Family Marriage Records (Anna M. Hendricks and John A. Morris), in Pennsylvania Marriages, 1709-1940 (Northumberland County, FHL microfilm 961,094). Salt Lake City, Utah: Family History Library, 1890.

7. Hendricks Family Media Coverage. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1840-1880.

8. Hendricks, William M., in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

9. Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

10. U.S. Census (1840, 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880). Washington, D.C., Pennsylvania and Virginia: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

11. William Hendricks and Elizabeth Bright, in “Marriages.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, Saturday, 21 April 1860.

12. Wm. M. Hendricks, in “Borough Election” (also “Election” or “The Borough Election”). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 23 March 1861, 23 February 1867, and 20 February 1874.

13. Wm. M. Hendricks, in “Court Proceedings” (notice of his assistance in transporting prisoners to the penitentiary in Philadelphia). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 17 August 1872.

14. Wm. M. Hendricks, in “In Memoriam” (tribute resolutions by the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers upon Hendricks’ death). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 18 June 1875.

15. Wm. M. Hendricks, in “Local Affairs” (notice of Governor’s appointment of James Beard to take over William Hendricks’ job as Justice of the Peace, following Hendricks’ death). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 2 July 1875.

You must be logged in to post a comment.