Alternate Spellings of Surname: Keihl, Kiehl

Court House, Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, circa early to mid-1800s (public domain).

A middle child, brought up in a civic-minded, nineteenth-century, Pennsylvania family that believed in bettering the communities its members called home, Theodore Kiehl was also a good son, who made sure to send money from his paycheck to his mother on a regular basis in order to make her life a little bit easier.

Had fate been kinder, he might have become a government official like his father, but that future was not to be.

Formative Years

Born in Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania circa 1837, Theodore Kiehl was a son of George W. Kiehl and Amelia (Heilman) Kiehl (1813-1899), who were married in Sunbury by the Rev. Albert Fisher on 18 October 1832. Sometime during the early 1840s, his father was elected as sheriff of Northumberland County.

In 1850, Theodore Kiehl resided in Sunbury with his parents and siblings: Oscar, who was born circa 1832 and was employed as a boatman; Ann Louise (1833-1910), who was born on 25 September 1833 and later wed Jared Clemson Irwin in Sunbury on 15 February 1852; Elizabeth (1835-1904), who was born on 7 November 1835 and later married L. C. Goodwin; Alice, who was born circa 1840; Louisa, who was born circa 1842; Amelia, who was born circa 1844; Charles Donnell (1847-1913), who was born on 1 August 1846; and Mary, who was born circa 1849.

Members of an increasingly prominent and respected family the Kiehls went about their daily lives as the decade unfolded—until tragedy struck. On 2 July 1856, their patriarch, George W. Kiehl, died in Sunbury.

Picking up the pieces of their lives, the family’s matriarch, Amelia (Heilman) Kiehl, assumed the roles of single mom and head of the Kiehl family’s household in Sunbury. By the time that a federal census enumerator arrived on her doorstep in 1860, she had pinched enough pennies to build a personal estate valued at two hundred dollars (roughly $7,400 in 2024 dollars). Residing with her were her children: Louisa, Amelia, Charles, Mary, and Clara, who had been born circa 1854. Her children, Oscar and Alice, were both documented as living nearby in another home.

Civil War — Three Months’ Service

Court House, Sunbury, Pennsylvania, 1851 (James Fuller Queen, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Following President Abraham Lincoln’s 15 April 1861 call for 75,000 volunteers “to favor, facilitate, and aid this effort to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union, and the perpetuity of popular government; and to redress wrongs already long enough endured,” John Peter Shindel Gobin, an attorney from Sunbury, Northumberland County, Pennsylvania traveled to Harrisburg, Dauphin County on Thursday morning, 18 April, to personally offer the services of the Sunbury Guards to Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin to help the Keystone State fulfill the president’s request at the earliest possible hour.

* Note: Andrew G. Curtin, the fifteenth Governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, would later create a network of soldiers’ orphans’ schools to educate and care for the children of Pennsylvania’s volunteer soldiers. The Sunbury Guards was a local militia unit with a long history of distinguished service to the city, county and state.

After Governor Curtin accepted Gobin’s offer, Gobin returned home to Sunbury to finish his recruiting efforts. Among those choosing to enlist with the Sunbury Guards at this time was Theodore Kiehl. On Friday evening, 19 April 1861, the Sunbury Guards assembled in the grand jury room at the Sunbury Court House, where they unanimously elected Charles J. Bruner as Captain, J. P. S. Gobin as first lieutenant and Joseph H. McCarty as second lieutenant.

The next morning, Captain Bruner took forty of his Sunbury Guards to the train depot and on to the state capital, making the Sunbury Guards the first military unit to leave Northumberland County to fight the growing southern rebellion. The town turned out early to give their fathers, brothers and sons a buoyant sendoff. Led by Sergeant C. Israel Pleasants, the remaining thirty-eight Sunbury Guardsmen worshipped at Sunbury’s Lutheran Church the next day in preparation for their own train trip to Harrisburg on 22 April 1861. Reunited later that day, the seventy-eight Sunbury Guardsmen officially mustered into service at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg on 23 April, and were designated as Company F in the 11th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (although they still employed their hometown Guards’ designation with pride).

But twenty-three-year-old Theodore Kiehl was not part of that seventy-eight-member team. He would later find a way around this rebuff, but for now, he was forced to watch his neighbors and friends march off to war while he remained at home. After re-enrolling for Civil War service in Blair County, Pennsylvania, he then was finally allowed to muster in, which he did at Camp Curtin on 2 May 1861. Entering at the rank of private, he was assigned to Company I of the 14th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Military records at the time described him as a twenty-three-year-old clerk from Northumberland County.

Serving under Captain Alexander Bobb and First Lieutenant J. C. Saunders, Private Theodore Kiehl and his fellow 14th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered to head for Lancaster, Pennsylvania, where they remained until 3 June. They were then moved to Chambersburg, where they were attached to the 5th Brigade of Brigadier-General James Scott Negley, under Major-General William High Keim, in the Union Army corps commanded by Major-General Robert Patterson. Stationed there until 16 June, they were then transported to Hagerstown, Maryland, where they remained until they were relocated to Sharpstown on 20 June. Stationed there until 2 July, they participated that day in the Battle of Falling Waters, which was the first Civil War battle in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. (A second battle with a different military configuration occurred there in 1863.) Also known as the Battle of Hainesville or Hoke’s Run, this first Battle of Falling Waters helped pave the way for the Confederate Army victory at Manassas later that month.

Assigned to occupation duties at Martinsburg the next day, they were then ordered to advance to Bunker Hill on 15 July and to Charlestown on 18 July. Three days later, they skirmished there with Confederate troops. That same day (21 July), they moved on to Harper’s Ferry and then to Carlisle, Pennsylvania before they were honorably mustered out on 8 August 1861.

Civil War — Three Years’ Service

First State Color, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (presented to the regiment by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, 20 September 1861; retired 11 May 1865, public domain).

Understanding that America’s Union was still in jeopardy, Theodore Kiehl chose to sign up for another tour of duty with the Union Army. This time, though, he was able to join his preferred military unit—the Sunbury Guards, the majority of whom had decided to reenlist after returning home from their own Three Months’ Service. A battle-hardened group, they were chosen to become the color guard unit of an entirely new regiment that had just been authorized by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin on 5 August 1861—the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Designated as Company C, the Sunbury Guardsmen would be responsible for carrying and protecting the American flag, ensuring that it would never fall into enemy hands—no matter how heated the combat they would face.

After re-enrolling for military service at the Court House in Sunbury, Pennsylvania on 19 August 1861, Theodore Kiehl officially re-mustered for duty as a private with Company C at Camp Curtin on 2 September. Military records at the time described him as a twenty-four-year-old boatman from Sunbury who was five feet, eight inches tall with sandy hair, gray eyes and a sandy complexion.

* Note: Mustering in from mid-August through early September at Camp Curtin under the leadership of Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, Company C’s roster of soldiers reached a total of 101 men by 17 September. Among Company C’s ranks were both the youngest and oldest members of the regiment, John Boulton Young (aged twelve) and Benjamin Walls (aged sixty-five).

In a letter sent to family during Company C’s earliest days, Captain Gobin provided these details regarding his regiment’s status:

We expect to leave tonight for Washington or Baltimore. Our company has been made the color company of the regiment, the letter being accorded to rotation used, C. It is the same as E in the 11th. Wm. M. Hendricks has been appointed Sergeant Major, so that Sunbury is pretty well represented in the regiment, having the Quartermaster, Sergeant Major and Color Company…. Boulton is lying by me as I write, just about going to sleep.

The U.S. Capitol Building, unfinished at the time of President Abraham Lincoln’s first inauguration, was still not completed when the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Washington, D.C. in September 1861 (public domain).

Following a brief training period in light infantry tactics, during which time the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were housed at Camp Curtin No. 2, which was located on the field next to the main camp, the men of Company C were then transported by train with their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to Washington, D.C. where, beginning 21 September, they were stationed roughly two miles from the White House at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown.

“It is a very fine location for a camp,” wrote Captain Gobin. “Good water is handy, while Rock Creek, which skirts one side of us, affords an excellent place for washing and bathing.”

Henry Wharton, a musician from C Company penned the following update for the Sunbury American on 22 September:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

I am happy to inform you that our young townsman, Mr. William Hendricks, has received the appointment of Sergeant Major to our Regiment. He made his first appearance at guard mounting this morning; he looked well, done up his duties admirably, and, in time, will make an excellent officer. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope for an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

On 24 September, the men of Company C became part of the federal military service, mustering in with great pomp and gravity to the United States Army with their fellow members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Three days later, the 47th Pennsylvania was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania was on the move again. Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen marched behind their regimental band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (one hundred and sixty-five steps per minute using thirty-three-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated close to the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (also known as “Baldy”), and were now part of the massive U.S. Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

The Big Chestnut Tree, Camp Griffin, Langley, Virginia, 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” in reference to the large chestnut tree located within their campsite’s boundaries. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly ten miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a letter home in mid-October, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin (the leader of C Company who would be promoted in 1864 to lead the entire 47th Regiment) reported that companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left-wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops:

I was ordered to take my company to Stewart’s house, drive the Rebels from it, and hold it at all hazards. It was about 3 o’clock in the morning, so waiting until it was just getting day, I marched 80 men up; but the Rebels had left after driving Capt. Kacy’s company [H] into the woods. I took possession of it, and stationed my men, and there we were for 24 hours with our hands on our rifles, and without closing an eye. I took ten men, and went out scouting within half a mile of the Rebels, but could not get a prisoner, and we did not dare fire on them first. Do not think I was rash, I merely obeyed orders, and had ten men with me who could whip a hundred; Brosius, Piers [sic, Pyers], Harp and McEwen were among the number. Every man in the company wanted to go. The Rebels did not attack us, and if they had they would have met with a warm reception, as I had my men posted in such a manner that I could have whipped a regiment. My men were all ready and anxious for a ‘fight.

In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

A Sad, Unwanted Distinction

The Kalorama Eruptive Fever Hospital (also known as the Anthony Holmead House) in Georgetown, D.C. after it was destroyed in a Christmas Eve fire in 1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

On 17 October 1861, death claimed the first member of the entire regiment—the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ little drummer boy, John Boulton Young. The pain of his loss was deeply and widely felt; Boulty (also spelled as “Boltie”) had become a favorite not just among the men of his own C Company, but of the entire 47th. After contracting Variola (smallpox), he was initially treated in camp, but was shipped back to the Kalorama eruptive fever hospital in Georgetown when it became evident that he needed more intensive care than could be provided at the 47th’s regimental hospital in Virginia.

According to Lewis Schmidt, author of A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, Captain Gobin wrote to Boulty’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Mitchell Young of Sunbury, “It is with the most profound feelings of sorrow I ever experienced that I am compelled to announce to you the death of our Pet, and your son, Boulton.” After receiving the news of Boulty’s death, Gobin said that he “immediately started for Georgetown, hoping the tidings would prove untrue.”

Alas! when I reached there I found that little form that I had so loved, prepared for the grave. Until a short time before he died the symptoms were very favorable, and every hope was entertained of his recovery… He was the life and light of our company, and his death has caused a blight and sadness to prevail, that only rude wheels of time can efface… Every attention was paid to him by the doctors and nurses, all being anxious to show their devotion to one so young. I have had him buried, and ordered a stone for his grave, and ere six months pass a handsome monument, the gift of Company C, will mark the spot where rests the idol of their hearts. I would have sent the body home but the nature of his disease prevented it. When we return, however, if we are so fortunate, the body will accompany us… Everything connected with Boulty shall by attended to, no matter what the cost is. His effects that can be safely sent home, together with his pay, will be forwarded to you.

Also according to Schmidt, Gobin added the following details in a separate letter to friends:

The doctor… told me it was the worst case he ever saw. It was the regular black, confluent small pox… I had him vaccinated at Harrisburg, but it would not take, and he must have got the disease from some of the old Rebel camps we visited, as their army is full of it. There is only one more case in our regiment, and he is off in the same hospital.

Boulty’s death even made the news nationally via Washington newspapers and the Philadelphia Inquirer. Just thirteen years old when he died, John Boulton Young was initially interred at the Military Asylum Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Established in August 1861 on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home, the cemetery was easily seen from a neighboring cottage that was used by President Abraham Lincoln and his family as a place of respite.

In letters home later that month, Captain Gobin asked Sunbury residents to donate blankets for the Sunbury Guards:

The government has supplied them with one blanket apiece, which, as the cold weather approaches, is not sufficient…. Some of my men have none, two of them, Theodore Kiehl and Robert McNeal, having given theirs to our lamented drummer boy when he was taken sick… Each can give at least one blanket, (no matter what color, although we would prefer dark,) and never miss it, while it would add to the comfort of the soldiers tenfold. Very frequently while on picket duty their overcoats and blankets are both saturated by the rain. They must then wait until they can dry them by the fire before they can take their rest.

On Friday, 22 October, the 47th engaged in a morning Divisional Review, described by Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.”

In early November, Captain Gobin observed that “the health of the Company and Regiment are in the best condition. No cases of small pox [sic] have appeared since the death of Boultie.” A few patients remained in the hospital with fever, including D. W. Kembel and another member of Company C. Gobin reported that Kembel was “almost well.”

Half of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, including Company C, were next ordered to join parts of the 33rd Maine and 46th New York in extending the reach of their division’s picket lines, which they did successfully to “a half mile beyond Lewinsville,” according to Captain Gobin.

In his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed still more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

Then, on 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review overseen by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges…. After the reviews and inspections, Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ outstanding performance during this review and in preparation for the even bigger adventures yet to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan directed his staff to ensure that new Springfield rifles were obtained and distributed to every member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

As the holidays approached, Regimental Quartermaster James Van Dyke, who was enjoying an approved furlough at home in Sunbury, Pennsylvania, was able to procure “various articles of comfort, for the inner as well as the outer man,” according to the 21 December 1861 edition of the Sunbury American. Upon his return to camp, many of the 47th Pennsylvanians of German heritage were pleasantly surprised to learn that the well-liked former sheriff of Sunbury had thoughtfully brought a sizable supply of sauerkraut with him. The German equivalent of “comfort food,” this favored treat warmed stomachs and lifted more than a few spirits that first cold winter away from loved ones.

1862

The City of Richmond, a sidewheel steamer that transported Union troops during the Civil War (Maine, circa late 1860s, public domain).

The New Year brought hope to the Kiehl family back home in Sunbury when they received word that Private Theodore Kiehl would be sending them twenty-five dollars from his military pay to help out the family’s matriarch.

Having been ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were transported by rail to Alexandria, where they boarded the steamship City of Richmond in order to sail the Potomac River to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped before they were marched off again for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C.

The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped aboard Baltimore & Ohio Railroad cars and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the United States Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship U.S. Oriental.

Ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamers on 27 January, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers commenced boarding the Oriental for the final time, with the officers stepping aboard last. Then, per the directive of Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, they steamed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. They were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Fort Taylor (Key West) and Fort Jefferson (Dry Tortugas).

Alfred Waud’s 1862 sketch of Fort Taylor and Key West, Florida (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

In February 1862, Private Theodore Kiehl and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians arrived in Key West to assume garrison duties at Fort Taylor. Initially pitching their Sibley tents on the beach after disembarking, they were gradually reassigned to improved quarters. During this phase of duty, they drilled daily in heavy artillery tactics and other military strategies, felled trees, helped to build new roads, and strengthened the fortifications in and around the Union Army’s presence at Key West and began to introduce themselves to locals by parading through the town’s streets during the weekend of Friday, 14 February. They also attended area church services that Sunday—a community outreach activity they would continue to perform on and off for the duration of their Key West service.

But while there were pleasant moments, there was also more frustration and heartache—the time here for the 47th made more difficult by the presence of typhoid fever and other tropical diseases, as well as the always likely dysentery from soldiers living in close, unsanitary conditions. A significant number of 47th Pennsylvanians were ultimately discharged via surgeons’ certificates of disability.

In a letter penned from the Judicial Department Headquarters in Key West on 30 March 1862, C Company Captain Gobin wrote:

Henry W. Wolf has been very sick, but is almost well again. He had the Typhoid fever. The fever is broke, but he is weak yet. He will go on duty in a day or two. Theodore Keihl [sic?] is the only sick man I have now that is at all bad, and he is not dangerous. Sam Miller was in the Hospital but he came back this morning. The weather is very warm. The [two illegible words] commences on Tuesday after which all [repels?] will be searched before allowed to come in. By this means we will keep off the Yellow fever which is the only thing dangerous. One of my men (Whisler) was bit by a scorpion yesterday but took precautionary measures instantly and no danger is apprehended. But my sheet is full. Remember me to all friends. Write soon. God bless you all.

Your

J. P. Shindel Gobin

Attached to a letter written on 10 April 1862 by Henry Wharton from the Court Room in the Key West Barracks, where Captain Gobin was getting up to speed with his new job as Judge Advocate General for the city of Key West, Gobin wrote the following note to his family and friends back home in Sunbury:

I did not think I would have time to add a word, but I did not get this in the mail this afternoon, and tonight after eleven [illegible word] I get an opportunity to scribble this. Four letters were rcvd and I was glad to hear from you. I am kept very busy but have got a house, and get along [fully?]. I like my new position despite the hard work. My men are getting along very well. Theo Keihl [sic] is in the Hospital, but is nearly well. [Illegible name due to damaged letter segment which was poorly repasted] is well but weak. The rest are all well. Remember me to all friends.

Your Shindel

This 1856 map of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad shows the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina in relation to the towns of Beaufort and Pocotaligo (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina from mid-June through July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers camped near Fort Walker before relocating to the Beaufort District in the U.S. Army’s Department of the South, roughly thirty-five miles away. Frequently assigned to hazardous picket detail north of their main camp, which put them at increased risk from enemy sniper fire, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania became known for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” and “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan,” according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

That same month, Private Theodore Kiehl sent an additional fifteen dollars from his military pay to his mother in Sunbury.

Victory and First Blood

Sent on a return expedition to Florida as September 1862 waned, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers saw their first truly intense moments of military service when their respective companies participated with other Union regiments in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff from 1 to 3 October.

Commanded by Brigadier-General Brannan, the 47th Pennsylvanians disembarked with a 1,500-plus Union force at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek from troop carriers guarded by Union gunboats.

Earthworks surrounding the Confederate battery on Saint John’s Bluff above the Saint John’s River in Florida (J. H. Schell, 1862, public domain).

Taking point, the 47th Pennsylvanians then led the 3rd Brigade through twenty-five miles of dense, pine forested swamps populated with deadly snakes and alligators. By the time the expedition ended, the Union brigade had forced the Confederate Army to abandon its artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff. According to Henry Wharton, “On the day following our occupation of these works the guns were dismounted and removed on board the steamer Neptune, together with the shot and shell, and removed to Hilton Head. The powder was all used in destroying the batteries.”

Meanwhile that same weekend (Friday and Saturday, 3-4 October 1862), Brigadier-General Brannan, who was quartered on board the Ben Deford as the Union expedition’s commanding officer, and other Union officers serving under Brannan, were busy penning reports to their respective superiors, and were also planning their next move to further secure this region of Florida, which had been deemed of key strategic importance by senior Union military leaders due to the significant role the state had been playing as a supplier of food to the Confederacy.

On Saturday, Brannan chose several officers to direct their subordinates to prepare rations and ammunition for a new expedition that would take them roughly twenty miles upriver to Jacksonville. (A sophisticated hub of cultural and commercial activities with a racially diverse population of more than two thousand residents, the city had repeatedly changed hands between the Union and Confederacy until its occupation by Union forces on 12 March 1862.) Among the Union soldiers selected for this mission were 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers from Company C, Company E and Company K.

One of the first groups to depart—Company C of the 47th Pennsylvania—did so that Saturday as part of a small force made up of infantry and gunboats, the latter of which were commanded by Captain Charles E. Steedman. Their mission was to destroy all enemy boats they encountered to stop the movement of Confederate troops throughout the region. Upon arrival in Jacksonville later that same day, the infantrymen were charged by Brannan with setting fire to the office of that city’s Southern Rights newspaper. Before that action was taken, however, Captain Gobin and his subordinate, Henry Wharton, who had both been employed by the Sunbury American newspaper in Sunbury, Pennsylvania prior to the war, salvaged the pro-Confederacy publication’s printing press so that Wharton could more efficiently produce the regimental newspaper he had launched while the 47th Pennsylvania was stationed at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida.

On Sunday, 5 October, Brannan and his detachment sailed away for Jacksonville at 6:30 a.m. Per Wharton, the weekend’s events unfolded as follows:

As soon as we had got possession of the Bluff, Capt. Steedman and his gunboats went to Jacksonville for the purpose of destroying all boats and intercepting the passage of the rebel troops across the river, and on the 5th Gen. Brannan also went up to Jacksonville in the steamer Ben Deford, with a force of 785 infantry, and occupied the town. On either side of the river were considerable crops of grain, which would have been destroyed or removed, but this was found impracticable for want of means of transportation. At Yellow Bluff we found that the rebels had a position in readiness to secure seven heavy guns, which they appeared to have lately evacuated, Jacksonville we found to be nearly deserted, there being only a few old men, women, and children in the town, soon after our arrival, however, while establishing our picket line, a few cavalry appeared on the outskirts, but they quickly left again. The few inhabitants were in a wretched condition, almost destitute of food, and Gen. Brannan, at their request, brought a large number up to Hilton Head to save them from starvation, together with 276 negroes—men, women, and children, who had sought our protection.

Receiving word soon after his arrival at Jacksonville that “Rebel steamers were secreted in the creeks up the river,” Brigadier-General Brannan ordered Captain Charles Yard of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Company E to take a detachment of one hundred men from his own company and those of the 47th’s Company K, and board the steamer Darlington “with two 24-pounder light howitzers and a crew of 25 men.” All would be under the command of Lieutenant Williams of the U.S. Navy, who would order the “convoy of gunboats to cut them out.”

According to Brigadier-General Brannan, the Union party “returned on the morning of the 9th with a Rebel steamer, Governor Milton, which they captured in a creek about 230 miles up the river and about 27 miles north [and slightly west] from the town of Enterprise.… On the return of the successful expedition after the Rebel steamers … I proceeded with that portion of my command to St. John’s Bluff, awaiting the return of the Boston.”

Integration of the Regiment

Meanwhile, as those activities were unfolding at Saint John’s Bluff, Yellow Bluff, Jacksonville, and aboard the Governor Milton, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was making history back in South Carolina when it became an integrated regiment on Sunday, 5 October 1862—three months before President Abraham Lincoln officially issued the Emancipation Proclamation.

Mop Up and Return to Headquarters

As that integration of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was taking place in Beaufort, South Carolina, Brigadier-General Brannan’s expeditionary force was winding down its activities in Duval County, Florida. According to a letter penned by Private William Brecht of the 47th Pennsylvania’s K Company, once the artillery pieces were carried away from Saint John’s Bluff by Brannan’s troops, Brannan ordered Captain Henry D. Woodruff of the 47th’s D Company to take his company as well as men from Company F and Company I to “blow up the fort, which was done with the most terrific explosions, filling the air for a great distance with fragments of timber and sand.”

“And thus came to an end Fort Finnegan, on St. John’s Bluff,” mused Brecht, who added that “after we destroyed the fort and it exploded into the air, the steamer Cosmopolitan which had been damaged and was full of water, we pumped out and fixed up again.”

Recapping the activities of his troops for his superiors, Brannan subsequently stated that, on Saturday, 11 October, “I embarked the section of the 1st Connecticut Battery, with their guns, horses, &c., and one company of the 47th on board the steamer Darlington, sending them to Hilton Head via Fernandina, Fla.”

[T]he Boston having returned, I embarked myself, with the last remaining portion of my command, except one company of the 47th left to assist and protect the Cosmopolitan…which was stuck on the bar…for Hilton Head, S.C., on the 12th instant, and arrived at that place on the 13th instant. The captured steamer Governor Milton I left in charge of Capt. Steedman, U.S. Navy and Cpl. Nichols.

According to Schmidt:

Company F embarked for Hilton Head on Friday and arrived home on Sunday, while Company D embarked on Saturday…but did not leave the St. John’s River til Sunday…. Some of the troops, including Company C, had returned to Beaufort on Saturday, October 11, but at least portions of Company K did not return until the following Tuesday. Returning with Company C was Capt. Gobin, who had contracted intermittent fever during the expedition and was hospitalized as soon as he returned….

Company D arrived back at Hilton Head on Saturday, and Company B and F on Sunday; and by Monday, October 13, most of the troops were back in camp in Beaufort, including Companies, A, G and K which arrived on this date. Company E did not arrive until Wednesday and Company H on Thursday night.

Fortunately, Captain Gobin was able to return to active duty on 20 October. Crediting his recovery to “good nursing and an abundance of quinine,” he resumed his leadership of the 47th Pennsylvania’s C Company, which had returned to South Carolina nine days earlier.

The day of 20 October also proved to be an important date for the regiment because The New York Times published a letter that had been penned six days earlier by Wharton. Recapping the events of the Saint John’s Bluff Expedition and subsequent successes by Brigadier-General Brannan’s troops, it also included the following insights:

Gen. BRANNAN thinks it evident, from his experience on this expedition, that the rebel troops in this portion of the country have not sufficient organization and determination, in consequence of their living in separate and distinct companies, to sustain any position, but seem rather to devote themselves to a system of guerrilla warfare. This was exemplified by the advance on St. John’s Bluff, where, after evacuating the fort, they continued to hover on our flanks and front, but did not come near enough to make their fire effective. We learned at Jacksonville that they commenced evacuating the Bluff immediately after our surprise of their pickets at Mount Pleasant Creek.

That same month, Private Theodore Kiehl sent an additional twenty-five dollars from his military pay to his mother in Sunbury.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

Pocotaligo-Coosawhatchie Expedition, South Carolina, 22 October 1862. Blue Arrow: Mackay’s Point, where the U.S. Tenth Army began its march. Blue Box: Union troops (blue) and Confederate troops (red) in relation to the Pocotaligo bridge and town of Pocotaligo, the Charleston & Savannah Railroad, and the Caston and Frampton plantations (U.S. Army map, blue highlighting added by Laurie Snyder, 2023; public domain; click to enlarge).

From 21-23 October, Private Theodore Kiehl and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers engaged Confederate forces in the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point under the regimental command of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the men of the 47th were placed on point once again as part of the U.S. Tenth Army’s 1st Brigade. This time, however, their luck would run out.

Completing just three miles of the anticipated “seven or eight” that the primary group was expected to cover to reach its intended target, the Tenth Army infantrymen suddenly ran smack into strongly entrenched Confederate troops.

They fought valiantly, driving the Confederates up and across the Pocotaligo River. But they were forced to waste precious ammunition and physical energy to do so.

And those who were trying to reach the higher ground of the Frampton Plantation were pounded by Confederate artillery and infantry hidden in the surrounding forests.

As they continued their respective advances into the fire around them, the Union troops continued to engage the Confederates wherever they found them, pushing them into a four-mile retreat to the Pocotaligo Bridge. At this juncture, the 47th then relieved the 7th Connecticut, but after two hours of exchanging fire while attempting, unsuccessfully, to take the ravine and bridge, the men of the 47th were forced to withdraw to Mackay’s Point. They simply just did not have enough ammunition to finish the fight they had begun with so much determination.

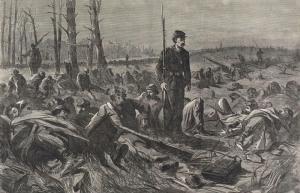

Losses for the 47th Pennsylvania at Pocotaligo were significant. Two officers and eighteen enlisted men died; an additional two officers and one hundred and fourteen enlisted were wounded.

Among those who were seriously injured was Private Theodore Kiehl, who was wounded in the face. Following treatment by regimental and division medical personnel, and a period of convalescence, he was able to return to duty with the regiment.

1863

Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers spent the year of 1863 and first two months of 1864 guarding federal installations in Florida as part of the U.S. Army’s Tenth Corps (X Corps) and Department of the South. Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor in Key West, under the command of Colonel Good, while Companies D, F, H, and K were placed under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander and assigned to garrison Fort Jefferson in Florida’s Dry Tortugas.

Far from being a punishment for the regiment’s recent combat performance, though, as several historians have claimed over the years, the return to Florida of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers was viewed by senior Union military officers as a critically important assignment because both forts were at continuing risk of attack and capture by foreign powers, as well as by Confederate States Army troops. The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were specifically chosen for this mission because of their “bravery and praiseworthy conduct” during the Battle of Pocotaligo,” as well as for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing” since the regiment’s founding in 1861.

Weakening Florida’s abilities to supply and transport food and troops throughout the area to the Confederate States by conducting raids on cattle ranches and salt production facilities, they also prevented foreign powers from assisting the Confederate Army and Navy in gaining control key points of entry in the Deep South.

In June 1863, Private Theodore Kiehl sent an even larger sum from his military pay to his mother—an impressive fifty dollars (the equivalent of roughly $1,850 in 2024 dollars).

Once again, though, water quality was a challenge for members of the regiment; as a result, disease became their constant companion and most dangerous foe. Even so, when their initial three-year terms of enlistment were about to expire, more than half of the officers and enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania opted to re-enroll for additional tours of duty with the regiment.

Among those choosing to re-enlist was Private Theodore Kiehl, who earned the coveted title of “Veteran Volunteer” after re-enrolling at Fort Taylor on 12 October 1863.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858 following the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. Per orders issued earlier in 1864 by Major-General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, that the fort be reclaimed to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade, Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of men from Company A were charged with expanding the fort and conducting raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. Graeffe and his men subsequently turned the fort into both their base of operations and a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate Army deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops.

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost-fully-reunited regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s Nineteenth Army Corps (XIX Corps), and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of two hundred and forty-five Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria, Louisiana with those prisoners on 9 April.)

Red River Campaign

Natchitoches, Louisiana (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 7 May 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The early days on the ground in Louisiana quickly woke the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers up to just how grueling this new phase of duty would be. From 14-26 March, most members of the regiment marched for Alexandria and Natchitoches, Louisiana, by way of New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington.

From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James Bullard, John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were then officially mustered in for duty on 22 June at Morganza. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “(Colored) Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long, harsh-climate trek through enemy territory, the 47th Pennsylvania encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill (now the Village of Pleasant Hill) on the night of 7 April.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, sixty members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads. The fighting waned only when darkness fell as those who were uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded. Finally, after midnight, the surviving Union troops were ordered to withdraw to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner and son of Zachary Taylor, former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

During this engagement, the 47th Pennsylvania recaptured a Massachusetts artillery battery that had been lost during the earlier Confederate assault. While he was mounting the 47th Pennsylvania’s colors on one of the recaptured Massachusetts caissons, C Company Color-Sergeant Benjamin Walls was shot in the left shoulder. As Walls fell, C Company Sergeant William Pyers was then also shot while preventing the American flag from falling into enemy hands. Both men survived their wounds and continued to fight on, but others from the 47th were less fortunate, including Private John C. Sterner (killed at Pleasant Hill), and Privates Cornelius Kramer, George Miller, and Thomas Nipple (wounded). In addition, the regiment nearly lost its second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel G. W. Alexander.

Still others from the 47th were captured, marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as prisoners of war (POWs) until released during prisoner exchanges beginning 22 July 1864. At least two men from the 47th never made it out of that camp alive; another member of the regiment died while being treated at the Confederate Army hospital in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Following what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, the 47th fell back to Grand Ecore, where the men engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications. After eleven days at Grand Ecore, they then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April. Marching forty-five miles that day, they arrived in Cloutierville at 10 p.m. While en route, they were attacked again—this time at the rear of their brigade, but they were able to quickly end the encounter and continue on.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April 1864), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Union Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on the Confederate cavalry of Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”).

Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s twenty-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops situated near a bayou and on a bluff, Brigadier-General Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending the other two brigades to find a safe spot where his Union troops could ford the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, other troops in Emory’s command worked their way across the Cane River, attacked Bee’s flank, forced a Rebel retreat, and erected a series of pontoon bridges, enabling the 47th and other remaining Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners.

In a letter penned from Morganza, Louisiana on 29 May, Henry Wharton described what had happened to the 47th Pennsylvanians during and immediately after making camp at Grand Ecore:

Our sojourn at Grand Ecore was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one on the boys, for by ten o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty-five miles. On that day the rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns, opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebel prisoners say it ‘seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth of this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton of Western Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to the Union officer who oversaw its construction, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, the 47th Pennsylvanians learned they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned yet again to the hard labor of fortification work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that enabled Union gunboats to more easily make their way back down the Red River. While stationed in Rapides Parish in late April and early May, according to Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits [sic] on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

On Sunday, May 15, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad wherewith the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired and we advanced ‘till dark, when the forces halted for the night, with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

Having entered Avoyelles Parish, they “rested on their arms” for the night, half-dozing without pitching their tents, but with their rifles right beside them. They were now positioned just outside of Marksville, Louisiana on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, the infantry advanced in line until they reached Mousoula [sic], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of our army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Continuing on, the surviving members of the 47th marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. While encamped there, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania in Beaufort, South Carolina (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864.

The regiment then moved on once again, and arrived in New Orleans in late June.

As they did during their tour through the Carolinas and Florida, the men of the 47th had battled the elements and disease, as well as the Confederate Army, in order to continue to defend their nation.

By June of 1864, Private Theodore Kiehl had sent a total of between two hundred and forty dollars and three hundred and fifteen dollars from his military pay to his mother at home in Sunbury. According to Susan Gobin, the sister of Theodore’s commanding officer, who attested that she had known Amelia Kiehl for thirty years, Amelia Kiehl “actually received two hundred and forty dollars from her said son’s pay, two hundred dollars thereof about the first of June 1864, and the remaining forty dollars sometime previously to that date.”

That amount that Private Theodore Kiehl sent home would be the equivalent of roughly $8,870 in 2024 dollars.

Ironically, on the Fourth of July—“Independence Day”—Private Kiehl learned from his superior officers that his independence from military life would not be happening anytime soon because the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had received new orders to return to the Eastern Theater of the war.

On 7 July 1864, he was among the first members of his regiment to depart Bayou Country. Boarding the U.S. Steamer McClellan, he sailed out of the harbor at New Orleans with his fellow C Company soldiers, along with the members of Companies A, D, E, F, H, and I.

An Encounter with Lincoln and Snicker’s Gap

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, they joined up with Major-General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July 1864. There, they fought in the Battle of Cool Spring and, once again, assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

On 24 July 1864, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin was promoted from leadership of Company C to the 47th Pennsylvania’s central regimental command staff, and was also awarded the rank of major.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Halltown Ridge, looking west with “old ruin of 123 on left,” where Union troops entrenched after Major-General Philip Sheridan took command of the Middle Military Division, 7 August 1864 (photo/caption: Thomas Dwight Biscoe, 2 August 1884, courtesy of Southern Methodist University).

Attached to the Middle Military Division, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah from August through November of 1864, it was at this time and place, under the leadership of legendary Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, that the members of the 47th Pennsylvania would engage in their greatest moments of valor. Of the experience, Company C’s Samuel Pyers said it was “our hardest engagement.”

Records of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers confirm that the regiment was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown in early August 1864, and engaged in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville, Middletown, Charlestown, and Winchester, Virginia as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

On 1 September 1864, First Lieutenant Daniel Oyster was promoted to the rank of captain of Company C. William Hendricks was promoted from second to first lieutenant, Sergeant Christian S. Beard was promoted to second lieutenant, Sergeant William Fry was promoted to the rank of first sergeant, and Corporal John Bartlow was promoted to the rank of sergeant. Private Timothy M. Snyder was also promoted to the rank of corporal that same day.

From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in the Battle of Berryville and engaged in related post-battle skirmishes with the enemy over subsequent days. On one of those days (5 September 1864), Captain Oyster and a subordinate, Private David Sloan, were wounded at Berryville, Virginia.

Color-Bearer Benjamin Walls, the oldest member of the entire regiment, was mustered out upon expiration of his three-year term of service on 18 September—despite his request that he continued to be allowed to continue his service to the nation. Privates D. W. and Isaac Kemble, David S. Beidler, R. W. Druckemiller, Charles Harp, John H. Heim, former POW Conrad Holman, George Miller, William Pfeil, William Plant, and Alex Ruffaner also mustered out the same day upon expiration of their respective service terms.

Valor and Persistence

Inflicting heavy casualties during the Battle of Opequan (also known as “Third Winchester”) on 19 September 1864, Sheridan’s gallant blue jackets forced a stunning retreat of Jubal Early’s grays—first to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September) and then, following a successful early morning flanking attack, to Waynesboro. These impressive Union victories helped Abraham Lincoln secure his second term as President. Recalling the battle years later, Sheridan noted:

My army moved at 3 o’clock that morning. The plan was for Torbert to advance with Merritt’s division of cavalry from Summit Point, carry the crossings of the Opequon at Stevens’s and Lock’s fords, and form a junction near Stephenson’s depot, with Averell, who was to move south from Darksville by the Valley pike. Meanwhile, Wilson was to strike up the Berryville pike, carry the Berryville crossing of the Opequon, charge through the gorge or cañon on the road west of the stream, and occupy the open ground at the head of this defile. Wilson’s attack was to be supported by the Sixth and Nineteenth corps, which were ordered to the Berryville crossing, and as the cavalry gained the open ground beyond the open gorge, the two infantry corps, under command of General Wright, were expected to press on after and occupy Wilson’s ground, who was then to shift to the south bank of Abraham’s creek and cover my left; Crook’s two divisions, having to march from Summit Point, were to follow the Sixth and Nineteenth corps to the Opequon, and should they arrive before the action began, they were to be held in reserve till the proper moment came, and then, as a turning-column, be thrown over toward the Valley pike, south of Winchester.”

By dawn on 19 September, the brigade from Wilson’s division headed by McIntosh had succeeded in compelling Confederate pickets to flee their Berryville positions with “Wilson following rapidly through the gorge with the rest of the division, debouched from its western extremity with such suddenness as to capture a small earthwork in front of General Ramseur’s main line.” Although “the Confederate infantry, on recovering from its astonishment, tried hard to dislodge them,” they were unable to do so, according to Sheridan. Wilson’s Union troops were then reinforced by the U.S. 6th Army.

I followed Wilson to select the ground on which to form the infantry. The Sixth Corps began to arrive about 8 o’clock, and taking up the line Wilson had been holding, just beyond the head of the narrow ravine, the cavalry was transferred to the south side of Abraham’s Creek.

The Confederate line lay along some elevated ground about two miles east of Winchester, and extended from Abraham’s Creek north across the Berryville pike, the left being hidden in the heavy timber on Red Bud Run. Between this line and mine, especially on my right, clumps of woods and patches of underbrush occurred here and there, but the undulating ground consisted mainly of open fields, many of which were covered with standing corn that had already ripened.

“The 6th Corps formed across the Berryville Road” while the “19th Corps prolonged the line to the Red Bud on the right with the troops of the Second Division.” According to Irwin, the:

First Division’s First and Second Brigades, under Beal and McMillan, formed in the rear of the Second Division and on the right flank. Beal’s First Brigade was on the right of the division’s position, and McMillan’s Second Brigade deployed on the left and rear of Beal; in order of the 47th Pennsylvania, 8th Vermont, 160th New York, and 12th Connecticut, with five companies of the 47th Pennsylvania deployed to cover the whole right flank of his brigade and to move forward with it by the flank left in front. By this time, the Army of West Virginia had crossed the ford and was massed on the left of the west bank.

While the ground in front of the 6th Corps was for the most part open, the 19th Corps found itself in a dense wood, restricting its vision of both the enemy and its own forces.

“Much time was lost in getting all of the Sixth and Nineteenth corps through the narrow defile,” Sheridan observed, adding that, because Grover’s division was “greatly delayed there by a train of ammunition wagons … it was not until late in the forenoon that the troops intended for the attack could be got into line ready to advance.” As a result:

General Early was not slow to avail himself of the advantages thus offered him, and my chances of striking him in detail were growing less every moment, for Gordon and Rodes were hurrying their divisions from Stephenson’s depot across-country on a line that would place Gordon in the woods south of Red Bud Run, and bring Rodes into the interval between Gordon and Ramseur.

When the two corps had all got through the cañon they were formed with Getty’s division of the Sixth to the left of the Berryville pike, Rickett’s division to the right of the pike, and Russell’s division in reserve in rear of the other two. Grover’s division of the Nineteenth Corps came next on the right of Rickett’s, with Dwight to its rear in reserve, while Crook was to begin massing near the Opequon crossing about the time Wright and Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] were ready to attack.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

More than a quarter of a century after the clash, Irwin conjured the spirit of the battle’s beginning:

About a quarter before twelve o’clock, at the sound of Sheridan’s bugle, repeated from corps, division, and brigade headquarters, the whole line moved forward with great spirit, and instantly became engaged. Wilson pushed back Lomax, Wright drove in Ramseur, while Emory, advancing his infantry [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] rapidly through the wood, where he was unable to use his artillery, attacked Gordon with great vigor. Birge, charging with bayonets fixed, fell upon the brigade of Evans, forming the extreme left of Gordon, and without a halt drove it in confusion through the wood and across the open ground beyond to the support of Braxton’s artillery, posted by Gordon to secure his flank on the Red Bud road. In this brilliant charge, led by Birge in person, his lines naturally became disordered….