Show me a hero and I’ll write you a tragedy.

– F. Scott Fitzgerald, Notebook E, 1945

The journey of Charles C. Detweiler and his family was one of hope and woe, taking its subjects from their Berks County beginnings to Montgomery, Northampton, Philadelphia, and Schuylkill counties and beyond, as they were educated, became war heroes, and leaders in the field of medicine and of their respective communities. As so often happens with life, fate frequently intervened, balancing their shining flashes of achievement with moments of darkness and death.

Formative Years

This mid to late 1800s photo of unidentified men repairing a road in Rockland Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania illustrates the rural nature of the community where Charles C. Detweiler and his siblings were reared (public domain).

Born on 20 August 1840 in Berks County, Pennsylvania, Charles C. Detweiler was a son of Berks County natives Charles Detweiler (1805-1889) and Catharine (Christman) Detweiler (1812-1887). According to Samuel T. Wiley’s Biographical and Portrait Cyclopedia of Schuylkill County:

His father, Charles Detweiler, was a native of Berks county, Pennsylvania, born near Kutztown, in 1805, where he was reared and lived until his death, in 1889. He was a carpenter by trade, which avocation he followed until advanced in years. In politics, he was a democrat until the breaking out of the war of the Rebellion, when he became a Republican. He served as school director of Rockland township, Berks county, for a number of years, and was a strong advocate of the public school system, of whom there were a great many at that time in Berks county. He was a member of the Reformed church for a number of years, in whose welfare and prosperity he was ever interested, giving always of his time and means liberally to its service…. He was married to Catharine Christman, by whom he had a family of nine children, seven sons and two daughters.

During the early 1840s, Charles C. Detweiler resided in Berks County with his parents and siblings, Isaac Charles (1830-1900), William C. (1831-1905), Peter Charles (1833-1919), Isabella C. (1836-1920), and Rosalinda/Rosalind (1838-1914), who had respectively been born in Kutztown, Maxatawny Township on 7 January 1830, 2 September 1831, 23 July 1833, 7 January 1836, and 11 August 1838. Two more sons—Washington Christman and Aaron C. Detweiler—then arrived, respectively, at their Berks County home on 22 November 1844 and 7 April 1847.

* Note: Another Detweiler child—Benjamin—was also reportedly born sometime during the 1830s or 1840s, but died at the age of three.

By 1850, this same family grouping was documented by a federal census taker as residents of Rockland Township, Berks County, and supported by family patriarch Charles Detweiler, who was employed as a carpenter. Also employed as a carpenter by 1860, the younger Charles C. Detweiler and his parents were documented on that year’s federal census as residents of Lobachsville, Rockland Township. Also still at home were Isabella, Washington and Aaron, as well as two-year-old Daniel Bahr.

But the family’s harmony would soon be disrupted as their nation began its descent into disunion and Civil War.

Civil War Military Service

At the age of 22, Charles C. Detweiler enrolled for Civil War military service in Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania on 16 September 1862. He then officially mustered in the next day at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County as a Private with Company A, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Military records at the time described him as a carpenter and resident of Allentown.

* Note: Company A was led by Captain Richard A. Graeffe, an 1847 émigré from Germany who had fought in the Mexican American War from 1847 to 1852 as a Corporal with Company E of the U.S. 4th Artillery, and who had then performed Three Month’s Service at the start of the U.S. Civil War as Captain of Company G of the 9th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry before being commissioned as an officer with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Private Charles Detweiler could not know it at the time, but he was joining the 47th Pennsylvania just as the regiment’s members were about to experience their first taste of combat.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina (October 1862)

The challenging environment of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad was illustrated by Harper’s Weekly in 1865.

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, Private Charles Detweiler and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers engaged Confederate States of America forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Ordered by Union military leaders to destroy the railroad there in order to disrupt the movement of CSA troops and supplies, the men of the 47th landed at Mackay’s Point with other troops from the Union’s 3rd Brigade, and were placed on point—but encountered trouble in fairly short order.

Picked off by snipers while on the move toward the Pocotaligo Bridge, they then faced massive resistance from a heavily entrenched and fortified CSA battery that opened fire on them as they entered and crossed a clearing. Those members of the Union detachment that were headed for the higher ground of the Frampton Plantation nearby fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests.

Aware they were in danger, the Union regiments fought back, grappling with Confederates where they found them, and pursuing the enemy for four miles as they retreated to the bridge, where the 47th then relieved the 7th Connecticut. But after two hours of intense, ammunition-depleting fighting, the 47th Pennsylvanians were forced to withdraw without taking the bridge or ravine.

In the days that followed, as Union leaders reviewed reports from the officers who had commanded troops that day, it quickly became clear that the 47th had incurred a significant number of casualties—two officers and 18 enlisted men killed in action, two officers and 114 enlisted men wounded. Although several officers reported that all of the bodies of 47th Pennsylvanians killed in action were retrieved and buried that terrible day, the graves of several still remain unidentified.

Ordered to return to South Carolina, the 47th Pennsylvania arrived at Hilton Head on 23 October 1862. A week later, several members were given the honor of serving as the guard detail at the funeral of Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South who had died from yellow fever on 30 October. (Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, was later named for him.)

1863

Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, the New Year for Private Charles C. Detweiler and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers was spent garrisoning federal installations in Florida as part of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps. Company A’s men joined those from companies B, C, E, G, and I in guarding Fort Taylor in Key West for much of 1863 while those from D, F, H and K companies were detached and sent to Fort Jefferson in Florida’s remote Dry Tortugas.

In February, Private Charles Detweiler was assigned to nursing duties at the fort’s hospital, an assignment he continued to hold through at least the month of March, according to Schmidt. This is a significant detail regarding his military service because this phase of duty was a challenging one for many members of the regiment—their time here made more difficult by the prevalence of disease. Plagued by chronic dysentery resulting from poor water quality and the often unsanitary living conditions arising from the close living quarters of the soldiers, a significant number of 47th Pennsylvanian Volunteers were also confined to the post hospital after being felled by typhoid and other tropical diseases. Several who did not survive were laid to rest with military honors at the post cemetery.

Despite these hardships, more than half of the regiment opted to re-enlist for a second tour of duty as the old year transitioned to the new.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania was ordered to expand the Union’s reach. As a result, Captain Graeffe and a group of men from A Company were assigned to special duty involving raids on CSA cattle herds as far north as Fort Myers in order to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across the region.

* Note: Abandoned in 1858 after the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians, Fort Myers had been deemed worthy of reclamation in 1864 by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, who felt the fort could render much needed support to the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade while also sheltering anyone fleeing Rebel troops, including Union sympathizers, escaped slaves and Confederate Army deserters.

According to Schmidt:

Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard. Lt. Harris was directed to tow the Matchless if necessary.

Punta Rassa was probably the location where the troops disembarked, and was located on the tip of the southwest delta of the Caloosahatchee River … near what is now the mainland or eastern end of the Sanibel Causeway… Fort Myers was established further up the Caloosahatchee at a location less vulnerable to storms and hurricanes. In 1864, the Army built a long wharf and a barracks 100 feet long and 50 feet wide at Punta Rassa, and used it as an embarkation point for shipping north as many as 4400 Florida cattle….

Capt. Graeffe and company were disembarked on the evening of January 7, and Gen. Woodbury ordered the company to occupy Fort Myers on the south side of the Caloosahatchee, about 12 miles from its mouth and 150 miles from Key West. Shortly after, [a detachment of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company stationed on Useppa Island] was also ordered to proceed to Fort Myers and join the main body of Company A, the entire command under direct orders of the General who was in the area…. Gen. Woodbury returned to Key West on the Honduras prior to January 19, and the command was left in charge of Capt. Graeffe who dispatched various patrols in search of refugees for enlistment and for activities involving Confederate cattle shipments.

Company A’s muster roll provides the following account of the expedition under command of Capt. Graeffe: ‘The company left Key West Fla Jany 4. 64 enroute to Fort Meyers Coloosahatche River [sic] Fla. were joined by a detachment of the U.S. 2nd Fla Rangers at Punta Rossa Fla took possession of Fort Myers Jan 10. Captured a Rebel Indian Agent and two other men.’

A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documents the time of Richard Graeffe and the men under his Florida command this way:

A small contingent of 20 men and two officers from the Pennsylvania 47th Regiment, led by Captain Henry Crain of the 2nd Regiment of Florida, arrived at the fort on January 7, 1864. A short time later, the party was joined by another small detachment of the 47th under the command of Captain Richard A. Graeffe. Over a short period, increasing reinforcements of the fort led to increasing cattle raids throughout the region. A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.

Early on, according to Schmidt, Captain Graeffe sent the following report to Woodbury:

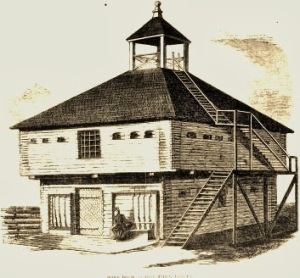

“At my arrival hier [sic] I divided my forces in three detachment, viz one at the Hospital one into the old guardhouse and one into the Comissary [sic] building, the Florida Rangers I quartered into one of the old Company quarters, I set all parties to work after placing the proper pickets and guards at the Hospital i have build [sic] and now nearly finished a two story loghouse of hewn and square logs 12 inches through seventeen by twenty-two fifteen feet high with a cupola onto the roof of six feet high and at right angle with two lines of picket fences seven feet high. i shall throw up a half a bastion around it as soon as completed. around the old guardhouse i have thrown up a bastion seven feet through at the foot and three feet on the top nine feet high from the bottom of the ditch and five on the inside. I also build [sic] a loghouse sixteen by eighteen of two storys [sic] Southeast of the Commissary building with a bastion around it at right angles with a picket fence each bastion has the distance you recomandet [sic] from the loghouses 20 feet on the sides and 20 to the salient angle, i caused to be dug a well close to bl. houses and inside of the bastions at each Station inside they are all comfortable fitted up with stationary bunks for the men without interfering with the defence [sic] of the work outside of the Bastions and inside the picket fense i have erected small kitchens and messrooms for each station, i am building now a guardhouse build [sic] of square hewn logs sixteen by sixteen two storys high the lower room to be used for the guard and the upper one as a prison, the building to be used for defence [sic] (in case of attack) by the Rangers each work is within view and supporting distance from the other; Capt. Crane with a detachment of his men repaired the wharf, which is in good condition now and fit for use, the bakehouse i got repaired, and the fourth day hier [sic] we had already very good fresh bread; the parade ground is in a good condition had all the weeds mowed off being to [sic] green to burn. i intend to fit up a schoolroom and church as soon as possible.”

Muster rolls for Company A from this period noted that “a detachment of 25 men crossed over to the north west side of the river” on 16 January and “scoured the country till up to Fort Thompson a distance of 50 miles,” where they “encountered a Rebel Picket who retreated after exchanging shots.” Making their way back, they swam across the river, and reached the fort on 23 January. Meanwhile, while that group was still away, Captain Graeffe ordered a smaller detachment of eight men to head out on 17 January in search of cattle. Finding only a few, they instead took possession of four barrels of Confederate turpentine, which were later disposed of by other Union troops.

Graeffe’s men also captured three Confederate sympathizers at the fort, including a blockade runner and spy named Griffin and an Indian interpreter and agent named Lewis. Charged with multiple offenses against the United States, they were transported to Key West, where they were kept under guard by the Provost Marshal—Major William Gausler, third-in-command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

This phase of duty lasted until sometime in February of 1864. The detachment of the 47th which served under Graeffe at Fort Myers is labeled as the Florida Rangers in several publications, including The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, prepared by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert N. Scott, et. al. (1891). Several of Graeffe’s hand drawn sketches of Fort Myers were published in 2000 in Images of America: Fort Myers by Gregg Tuner and Stan Mulford.

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had already left on the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reconstituted regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.

But they had missed the two bloodiest combat engagements that the 47th Pennsylvania would endure during the Red River Campaign—the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield on 8 April and the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April. According to Schmidt, Company A was soon ordered to return the Confederate prisoners to New Orleans, and officially ended their detached duty on 27 April when they rejoined the main regiment’s encampment at Alexandria.

This means that the men from Company A also missed a third combat engagement—the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry”), which took place on 23 April.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” for Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, the officer overseeing its construction, this timber dam built near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage along challenging waters of the Red River (public domain).

Under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey from 30 April through 10 May, the fully reassembled 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined other Union troops in building a dam near Alexandria, Louisiana to enable federal gunboats to more easily navigate the Red River’s fluctuating water levels.

Beginning 13 May, A Company moved with the majority of the 47th from Simmsport across the Atchafalaya to Morganza, and then to New Orleans on 20 June before receiving orders on the 4th of July to return to the East Coast for further duty.

Removed from command amid the controversy over the Union Army’s successes and failures during the Red River Expedition, Union General Nathaniel P. Banks was placed on leave by President Abraham Lincoln. Banks subsequently spent much of his time in Washington, D.C. as a Reconstruction advocate for Louisiana.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Still able and willing to fight after their time in Bayou country, the soldiers of Company A and the men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies C, D, E, F, H, and I steamed eastward aboard the McClellan beginning 7 July 1864.

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, they joined up with General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July 1864. There, they fought in the Battle of Cool Spring and assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

Attached next to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah from August through November of 1864, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania then engaged in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Records of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers confirm that the regiment was assigned to defensive duties in Virginia in early August 1864, and engaged in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville and other locations (Middletown, Charlestown and Winchester) as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by CSA Lieutenant-General Jubal Early. From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania then fought in the Battle of Berryville, continuing to duke it out with Confederates over subsequent days in related post-battle skirmishes.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill (September 1864)

Together with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Philip Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company A and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians next helped to inflict heavy casualties on Early’s forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon”). The battle, also known as “Third Winchester,” is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After progressing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps’ advance bogged down for several hours, impeded by the massive movement of Union troops and their supply wagons. Unfortunately, this delay enabled Early’s Confederates to dig in.

As a result, when they finally reached the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with a daunting number of CSA soldiers. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Rebel artillery stationed on high ground. Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and their fellow 19th Corps members were directed by General William Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but many Union casualties ensued when another Confederate artillery group opened fire as Union troops tried to cross a clearing.

As a nearly fatal gap began to appear between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units commanded by Brigadier-Generals David A. Russell and Emory Upton. Russell, hit twice—once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers opened their lines long enough to enable Union cavalry forces led by William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

The 19th Corps, with the 47th in the thick of the fighting, then began whittling away and pushing the Confederates steadily back. Early’s men ultimately retreated in the face of the valor displayed by the “blue jackets.” Leaving 2,500 wounded behind, the Confederate Army retreated to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September), eight miles south of Winchester, and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union men which outnumbered Early’s three to one.

Sent out on skirmishing parties afterward, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania finally made camp at Cedar Creek. Moving forward, they would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but they would do so without two respected commanders: Colonel Tilghman Good and his second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, who mustered out on 23-24 September upon expiration of their respective terms of service. Fortunately, Good and Alexander were replaced by others equally admired both for their temperament and the front line experience: John Peter Shindel Gobin, Charles W. Abbott and Levi Stuber.

Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia (19 October 1864)

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, Surprise at Cedar Creek, which captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

It was during 1864 that General Philip Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s crop-production infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents—civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops—weakened by hunger—peeled off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally and win the day.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October 1864, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles—all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to historian, Samuel P. Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he rode rapidly past them – ‘Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’

The Union’s counterattack stomped Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions thusly:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went ‘whirling up the valley’ in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn, and no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

But, it proved to be another costly engagement for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, which was documented as having higher percentages of killed and wounded than many of the other regiments engaged that day. Of the more than 174 members of the regiment declared killed, wounded, captured, or missing, 40 members of the 47th were killed outright with another 99 wounded in action—15 of whom later died—including Private Charles C. Detweiler, whose valiant fight to live was described by Acting Assistant Surgeon J. T. Goddard the U.S. Office of the Surgeon General:

A wet preparation of portions of the left profunda and femoral arteries, ligated for secondary hemorrhage after gunshot.

Private C. D., “A,” 47th Pennsylvania, 24: musket ball through middle third of thigh, injuring femur, Cedar Creek, Va., 19th October, 1864; admitted hospital, Philadelphia, 10th February; hemorrhage from descending branch of the external circumflex, 4th March; profunda ligated near its origin by Acting Assisting Surgeon W. P. Moon, 5th; hemorrhage from femoral, which was ligated just below origin of profunda by Acting Assistant Surgeon Moon, 9th; died, 12th March, 1865.

Death and Interment

Death Certificate for Private Charles C. Detweiler, 12 March 1865, City of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania (public domain).

Although some records noted that Private Charles C. Detweiler died at the Union Army’s Mower General Hospital in Philadelphia of battle wound-related complications on 12 February 1865, the aforementioned death date of 12 March 1865 is the correct one, supported both by this soldier’s death certificate and the death date on his gravestone.

His cause of death was described by W. P. Moore, M.D. on the physician’s death certificate filed with the City of Philadelphia as “Exhaustion following G.S.W.” This same document also noted that Private Charles C. Detweiler had been an unmarried farmer at the time of his passing.

Two days later, on 14 March 1865, Charles C. Detweiler’s remains were shipped back to his family in Berks County. Following funeral services, he was then laid to rest at the Fairview Cemetery in Kutztown.

Another Tragedy Averted

Astonishingly, while still grieving the loss of their son, Charles C. Detweiler, Charles and Catharine Detweiler then suffered another close call—nearly losing another of their sons to combat-related injuries. Barely two weeks after the remains of their 24-year-old son had been returned home for burial, their 18-year-old son then sustained a serious gunshot wound (“Vulnus Sclopet”) to his right arm while fighting in the Battle of Hatcher’s Run Virginia.

But this time, the outcome was different. A corporal with Company G of the 198th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Aaron C. Detweiler survived penetration by a minie ball to the “soft parts” of the upper third of his arm on 29 March 1865. Initially treated on scene by regimental physicians, he was then transported to the Union Army’s Harewood General Hospital, where he was admitted as patient number 20,278. Treated by R. B. Bontecou, Surgeon, U.S. Volunteers, his hospital records noted that, “the condition of injured parts and constitutional state of patient were good” upon admission, adding, “Result favorable.”

What Happened to Charles Detweiler’s Family?

Following the funeral of Private Charles C. Detweiler, his family tried to put their grief behind them as they resumed their lives. By 1870, it was clear that they were succeeding. His siblings had all moved on to begin their own lives while their parents resided alone in the 9th Ward of Reading, Berks County, where their father was still employed as a carpenter with real and personal estate holdings valued at $13,650.

Their individual and collective journeys continued on in this relatively stable fashion for slightly more than a decade with multiple male members of the family completing medical or dental training prior to opening healthcare practices in communities across eastern Pennsylvania. But then fate intervened yet again, scything two more of Charles C. Detweiler’s siblings from the family fold with one sharp blow.

Newspapers and other publications nationwide, including the Reading Times, provided regular updates regarding what happened that terrible Summer of 1883:

Midnight Horror! Two of Reading’s Most Prominent Physicians Drowned. Death in the Schuylkill While Bathing of the Brothers Detweiler. ONE OF THE BODIES RECOVERED. News of the Drowning received at Midnight…. FULL PARTICULARS OF THE DREADFUL ACCIDENT…. One of the most ghastly and heartrending accidents that ever claimed citizens of Reading for its victims befell Drs. Aaron C. and Washington C. Detweiler last night. Both were well-known and rising physicians of this city, and a most profound sensation was created when the intelligence of the occurrence reached their families and friends, and from that time on until long after midnight there were groups of men and women to be seen at different points on South Fifth street and Chestnut street discussing the accident which yet is in some respects unexplained. It appears that about quarter of 9 o’clock Dr. A. C. Detweiler, Dr. W. C. Detweiler, his son Charles, and the hostler, a young man named Charles Matthias, went down to Lutz’s dam, a popular bathing resort near the sheet mill at the foot of Spruce street that is visited by hundreds of persons daily. All of them went into the dam, and for some lime enjoyed the cooling water with the greatest zest. About half-past 9 o’clock the hostler, who cannot swim, left the water and dressed. The two doctors and young Charles remained in the dam, the men becoming playful…. Dr. A. C. Detweiler and his nephew Charles were sporting together for awhile, when suddenly Charles’ uncle, who evidently got beyond his depth or was seized with an attack of cramp, cried for help. His brother, Dr. W. C. immediately went to his assistance, and Charles came out of the water and joined the hostler. This was at twenty minutes before 10 o’clock, and, the hostler stated to a Times reporter, as they heard no splashing in the water, they supposed that the cry for help had been made in jest. Charles Detweiler and the hostler waited on the river bank until after 10 o’clock, when they hailed a man who was passing down the river road, related what had occurred, and enlisted his aid in making a search for the whereabouts of the two doctors. The man got a lantern in the house adjoining the sheet mill, and having secured a boat and the services of another man, they pushed out into the river and shortly came upon the corpse of Dr. A. C. Detweiler. The body was floating in an erect posture, with the head hanging downward. The body was got out of the water about twenty minutes of 11 o’clock, but some time elapsed before it was brought to his late residence, No. 617 Chestnut street. Search for the body of his brother was given up until this morning.

Both the men were born in Rockland township, Berks county, and were brothers of Dr. Isaac C. Detweiler, who resides at No. 210 North Sixth street. Dr. Washington C. Detweiler, who resided at No. 221 South Fifth street, was in his 31st year, and leaves a wife and six children Charles, in his 17th year, John, Warren, Kate, Bessie, and a child about a year and a half old. He was a graduate of the Jefferson Medical College, and had one of the finest practices of any physician in Reading. Dr. Aaron C. Detweiler, who resided at No. 517 Chestnut street, was in his 37th year. He leaves a wife, but no children. He graduated from both the Jefferson Medical College and the University of Pennsylvania. He served with credit to himself in the Federal army during the late Rebellion. How both men came to be drowned in so singular a manner, remains to be explained. Several theories are advanced. The one which seems to obtain most general belief among those acquainted with the men and the place where the accident occurred is that Dr. A. C. Detweiler was either seized with cramp or was pulled into one of the deep holes in the dam by the strong undercurrent which is peculiar to the spot. His brother, going to his help, was then either pulled beyond his depth by the same current or went down in the death grasp of his brother, who weighed over 200 pounds while he was a man of comparatively slight build.

The double-barreled loss rocked not just the Detweiler family, but a significant number of households across Berks County because Aaron C. Detweiler, M.D. and Washington Christman Detweiler, M.D. had quickly become respected members of their communities following their respective 1869 and 1877 graduations from Philadelphia’s Jefferson Medical College. Following the coroner’s inquest into their 6 July 1883 drownings, the brothers were honored at well-attended funerals before being laid to rest at the Charles Evans Cemetery—Washington in Section F, Lot 64 and Aaron in Section K, Lot 4.

Just four years later, the family’s matriarch was also gone. On 29 September 1887, Catharine (Christman) Detweiler, died in Reading at the age of 75 in Reading, and was laid to rest at the Fairview Cemetery in Kutztown, Berks County.

Family patriarch Charles Detweiler then died two years later. After passing away in Reading at the age of 83 on 1 February 1889, he was laid to rest beside his wife.

Once again, the surviving Detweiler siblings tried to put their grief behind them, and once again, they succeeded in doing so for another decade. The next to shake off his mortal coil was Charles C. Detweiler’s brother, Isaac. A graduate of Hahnemann College in Philadelphia who had practiced medicine in Kutztown, Berks County for two years before opening a new practice in Reading, he had wed Eliza (Stettler) Detweiler, and lived to see the dawn of a new century before passing away in Reading on 29 August 1900. He was then laid to rest at the same cemetery where his parents had been buried—Kutztown’s Fairview Cemetery.

Five years later, the second oldest Detweiler sibling was also gone. A dentist who had opened a private practice in Easton, Northampton County, William C. Detweiler, D.D.S. lived a long, full life before passing away in Easton on 22 March 1905. Preceded in death in 1877 by his daughter, Ellen, he was survived by his wife, Amanda (Lynn) Detweiler, and their children: Horace Detweiler (1858-1911), Mary Ann (Detweiler) Shrope (1862-1933), and Oscar L. Detweiler (1868-1939).

After nearly another decade’s respite from grief, the Detweilers then lost sibling Rosalind. As the second oldest daughter, she had married William Fenstermacher Sell before welcoming the births of a daughter, Rebecca (1860-1930), and four sons: John (1865-1932), Harry D. (1869-1945), Isaac D. (1872-1935), and Peter D. (1873-1943). Felled by apoplexy in Philadelphia on 21 April 1914, she was laid to rest at the Westminster Cemetery in Bala Cynwyd, Montgomery County.

Five years later, the second dentist in the family—Peter Charles Detweiler, D.D.S.—was the next to pass on. Educated in the public schools of Berks County, he had pursued dentistry studies at the age of 21 prior to opening his office in Schuylkill Haven, Schuylkill County in 1856. According to Wiley’s Cyclopedia, he also owned “several ice-dams in the vicinity of Schuylkill county, [supplying] the ice-trade of that town…. In politics he [was] a prohibitionist, although formerly a republican,” was a member of the United Brethren Church, and also served on both his community’s school board and its borough council.

Married first to Rebecca A. Bowen (1837-1875), he greeted the arrival with her of three children—Samuel B. (1861-1936), Charles Eugene (1863-1892) and Eleanor Sophia Detweiler (1869-1929)—before being widowed by Rebecca on 3 March 1875. He then remarried—to Luzetta Horn (1851-1919)—and welcomed the births of Aaron Horn (1879-1942), George H. (1883-1953), Mollie Horn (1884-1960), Lulu (1885-1934), Mark Horn (1887-1918), and Ruth Horn Detweiler (1890-1970). After passing away in Schuylkill Haven on 28 May 1919, he was laid to rest at that city’s Schuylkill Haven Union Cemetery.

A year later, Isabella C. (Detweiler) Eckert was also gone. After a long, full life with her husband, William C. Eckert, a timekeeper for the Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, during which she greeted the arrival of son, Aaron Detweiler Eckert (1873-1937), and daughters, Katie D. (1864-1932) and Annie D. (1870-1961), she passed away in Reading, Berks County on 10 October 1920, and was laid to rest at the Charles Evans Cemetery.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

2. Charles Detweiler and Rosalind Sell, in Returns of Deaths in Philadelphia and in Death Certificates. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: City of Philadelphia, 12 March 1865 and 21 April 1914.

3. Detweiler, Charles, in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

4. Dr. Isaac C. Detweiler, in The Centennial History of Kutztown, Pennsylvania Celebrating the Centennial of the Incorporation of the Borough — 1815-1915. Kutztown, Pennsylvania: Press of the Kutztown Publishing Company, 1915.

5. Drs. Aaron C. Detweiler and Washington Detweiler, in Medical Memoranda, in The Medical Counselor, vol. VIII. Grand Rapids, Michigan: The Medical Counselor Publishing Company, 1884.

6. “Midnight Horror! Two of Reading’s Most Prominent Physicians Drowned. Death in the Schuylkill While Bathing of the Brothers Detweiler.” Reading, Pennsylvania: Reading Times, Saturday, 7 July 1883.

7. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

8. U.S. Census (1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900). Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

9. Wiley, Samuel T. Biographical and Portrait Cyclopedia of Schuylkill County (Dr. Peter C. Detweiler). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Rush, West and Company, Publishers, 1893.

10. Woodhull, Alfred A., Assistant Surgeon and Brevet Major, U.S. Army. Catalogue of the Surgical Section of the United States Army Medical Museum, (Case No. 1357: “C. D., A, 47th Pennsylvania”). Washington, D.C.: Office of the Surgeon General, U.S. Army, Government Printing Office, 1866.

You must be logged in to post a comment.