Alternate Presentations of Name: Scott W. Johnston, W. Scott Johnson, W. Scott Johnston, Washington Johnson, Washington Scott Johnston

“Madam,

Yours of September 1st 1865, inquiring how the name of your husband appeared on the Rolls & Records of the 47th Pa Vols, addressed to Col Gobin, was this day referred by him to me for investigation and report.

In reply I would state that our Records contain the name of Uriah Keiser, 45 years of age, 5 feet 10 1/2 inches high, Dark complexion, Blue Eyes, Black hair….”

College man. Attorney. Soldier. Union Army officer. Civil engineer.

W. Scott Johnston was all of these—and more. A leader in times of war and peace, he continued to look after and help the men who served under him during the American Civil War long after the war’s end.

Formative Years

Lafayette College, Easton, Pennsylvania (on hill, center) and the Delaware Bridge, as seen from Phillipsburg Rock, New Jersey, 1850 (James Fuller Queen, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Born in Readington Township, Hunterdon County, New Jersey on 8 January 1833, Washington Scott Johnston was a son of John J. and Eliza (Ten Eyck) Johnston.

In 1850, the federal census documented his residence in a dormitory at Lafayette College in Easton, Pennsylvania. A member of the Phi Kappa Sigma Fraternity’s Gamma Chapter in 1852, he later graduated from Lafayette College with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Engineering.

His entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives indicates that he was employed as a lawyer at the dawn of the Civil War.

Civil War Military Service

According to the Civil War Veterans’ Card File, W. Scott Johnston enrolled for military service on 27 March 1863 in Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, and then officially mustered in for duty as a Private with Company E of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on 5 April 1863 at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, Pennsylvania. Military records at the time described him as being 5 feet 7 inches tall with dark hair, hazel eyes and a “brown complexion,” although the latter descriptor may be a transcription error since there also appear to be other mistakes on this index card.

* Note: Various other military documents also place W. Scott Johnston’s enrollment date as March of 1863, and a pension record indicates that he also served with Company I of the 5th Pennsylvania Militia; however, the 1920 edition of the General Register of the Members of the Phi Kappa Sigma Fraternity, 1850-1920 reported that he enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania as a Private in 1861, and served with the regiment as an enlisted soldier until receiving his promotion to the rank of First Lieutenant and Adjutant in 1863. (His entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File states that the promotion occurred on 1 September 1864.)

An initial muster-in year of 1861 does appear to be the most likely date, however, since Johnston’s listing on one of the regiment’s muster rolls states that he “Joined by appointment of 1st Lt. & Adj’t. Sept. 1 1864 from Co. E” and since his entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File states that he was 28 at the time of his initial enrollment. (If he was born in 1833 and was actually 28 years old at the time of his entry into service, this would mean he would have had to muster in for duty in 1861.) Furthermore, his Civil War Veterans’ Card entry states that he re-enlisted for duty at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida on 12 February 1864. Typically, other men from this regiment who enlisted at Fort Taylor in 1863 or early 1864 did so after having completed their initial three-year terms of service which had begun in 1861 (meaning that, if W. Scott Johnston was “re-enlisting,” he was also most likely doing so after completing his own initial three-year term which had begun in 1861).

What is certain is that W. Scott Johnston served in various campaigns across the South with his regiment, including the 47th Pennsylvania’s 1863 defense of Florida and the Union’s Red River Campaign across Louisiana (from March to June 1864).

Red River Campaign

New Orleans, Opelousas & Great Western trains at the Algiers, Louisiana railroad shop, circa 1865 (public domain).

Boarding the steamer Charles Thomas in Florida on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. (The officers and men from Company A, who had been serving on detached duty at Fort Myers in Florida since early January, would not reconnect with the 47th Pennsylvania until late April.)

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reunited regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

From 14-26 March, the 47th passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville, Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches, Louisiana. From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James and John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for service with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were then officially mustered in for duty on 22 June at Morganza. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “(Colored) Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under Cook.”

Often short on food and water during the long, grueling journey, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, 60 members of the 47th Pennsylvania were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, its right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

During this engagement, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers recaptured a Massachusetts artillery battery that had been lost during the earlier Confederate assault. While he was mounting the 47th’s colors on one of the Massachusetts caissons, Color-Sergeant Benjamin F. Walls was shot in the left shoulder. As Walls fell, Sergeant William Pyers was then also shot while retrieving the American flag from Walls, thereby preventing it from falling into enemy hands.

In addition, Good nearly lost his second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, who had been severely wounded in both legs. Casualties among the enlisted men were also high, and a number of soldiers were captured and held as prisoners of war by Confederate forces at Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas until released during prisoner exchanges in July, August, September, or November. Tragically, at least two members of the 47th died while in captivity at the largest Confederate prison camp west of the Mississippi River, and the burial locations of others remain a mystery to this day, their bodies having been hastily interred on or between battlefields—or possibly in unmarked prison graves.

Following what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, the 47th Pennsylvanians fell back to Grand Ecore, where they remained for 11 days and engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications. They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April, arriving in Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night, after marching 45 miles. While en route, they were attacked again—this time at the rear of their brigade, but they were able to quickly end the encounter and continue on.

The next morning (23 April 1864), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee’s Confederate Cavalry in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”). Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s 20-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops situated near a bayou and on a bluff, Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending the other two brigades to find a safe spot where his Union troops could ford the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, other Emory troops worked their way across the Cane River, attacked Bee’s flank, forced a Rebel retreat, and erected a series of pontoon bridges, enabling the 47th and other remaining Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. Encamping overnight before resuming their march toward Rapides Parish, the 47th Pennsylvanians finally arrived on 26 April in Alexandria, where they camped for 17 more days.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” for the Union officer who ordered its construction, Lt.-Col. Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated the passage of Union gunboats (public domain).

During this phase of duty, the 47th Volunteers were temporarily placed under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey from 30 April through May 10, and helped build a dam across the Red River near Alexandria to enable federal gunboats to more easily navigate the river’s fluctuating water levels.

The Controversy

While these battles, marches, and other military actions were all unfolding, a controversial incident roiled not only the 47th Pennsylvania’s officers’ corps, but senior levels of the Union Army’s leadership in Louisiana.

The 11 May 1864 Evening Star in Washington, D.C. gave a glimpse into the situation with the startling news that Major William H. Gausler and First Lieutenants W. H. R. Hangen and William Reese of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had been dismissed from military service “for cowardice in the actions of Sabine Cross Roads and Pleasant Hill on the 8th and 9th of April, and for having tendered their resignations while under such charges” (AGO Special Order No. 169, 6 May 1864).

The allegations against the 47th Pennsylvania’s officers would continue to trouble the hearts and minds of Colonel Good and his men for months as the situation went unresolved—despite official protests that were lodged by Good and others who condemned the allegations of cowardice against Gausler, Hangen and Reese as grossly inaccurate and unfair. The stain was finally removed from the regiment when President Abraham Lincoln stepped in. According to The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, President Lincoln personally reviewed and reversed the Adjutant General’s findings against Gausler. On 14 October 1864, Lincoln wrote to U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton:

Please send the papers of Major Gansler [sic], by the bearer, Mr. Longnecker. A. LINCOLN

An annotation to Lincoln’s collected works explains that “Mr. Longnecker was probably Henry C. Longnecker of Allentown, Pennsylvania,” and makes clear that, although Major W. H. Gausler had indeed been dismissed for cowardice, President Lincoln disagreed with the decision, and overturned it on 17 October 1864. The notation further explains, “Although the name appears as ‘Gansler’ in Special Orders, it is ‘Gausler’ on the roster of the regiment.”

A more detailed explanation of why Colonel Good and his men were so angered by the allegations against Gausler and the others was later provided in Gausler’s 1914 obituary in The Allentown Leader:

“[Gausler] was court martialed for making a superior officer apologize on his knees at the point of a gun for slurring Pennsylvania German soldiers, but was pardoned by President Lincoln.”

Although the incident left a sour taste in the mouths of Colonel Good and his men, they did not let it deter them from their mission to preserve America’s Union and end the brutal practice of slavery across the nation. Beginning 13 May, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers moved from Simmesport to Morganza, and then to New Orleans on 20 June.

On the 4th of July, they received new orders, directing them to return to the East Coast. Their departure took place in two stages.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Beginning 7 July 1864, Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I of the 47th Pennsylvania steamed for the East Coast aboard the McClellan while Companies B, G and K remained behind on detached duty under the command of F Company Captain Henry S. Harte. Once they were able to secure transport later that month, the members of those three companies then also sailed for the East Coast. Arriving in Virginia on 28 July, they reconnected with the bulk of their regiment at Monocacy, Virginia on 2 August.

An Encounter with Lincoln and Snicker’s Gap

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln, the men from Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I were then ordered to join with Major-General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap, Virginia, where they engaged in the Battle of Cool Spring, and assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August, the opening days of September saw the promotion at Berryville, Virginia of several enlisted men and officers, including W. Scott Johnston, who was advanced to the rank of First Lieutenant and Adjutant with the regiment’s central command staff on 1 September 1864. A number of others from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers departed at this same time, mustering out upon expiration of their respective three-year service terms, including the captains of D, E and F Companies.

Those remaining behind, including First Lieutenant and Adjutant W. Scott Johnston, were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill

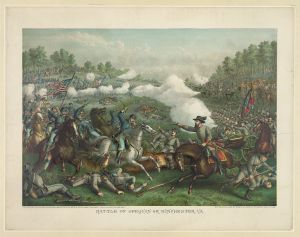

Together with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Philip H. (“Little Phil”) Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the 47th Pennsylvanian Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”).

The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

Philip Sheridan’s Union army defeating Jubal Early’s Confederate force (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893; U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. Advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. Finally reaching the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with Early’s Confederate Army. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and the 19th Corps were directed by Brigadier-General Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as another Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops trying to cross a clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice—once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

The 19th Corps, with the 47th in the thick of the fighting, then began pushing the Confederates back. Early’s “grays” retreated in the face of the valor displayed by Sheridan’s “blue jackets.” Leaving 2,500 wounded behind, the Rebels retreated to Fisher’s Hill, eight miles south of Winchester (21-22 September), and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union men which outnumbered Early’s three to one. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek.

Battle of Cedar Creek

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

During the fall of 1864, Major-General Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents—civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally and win the day.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles—all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he rode rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

The Union’s counterattack punched Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th fought so bravely that they would later be commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

Once again, the casualties for the 47th were high. Sergeant William Pyers, the C Company man who had so gallantly rescued the flag at Pleasant Hill was cut down and later buried on the battlefield. Sergeant Francis A. Parks and Private Marcus Berksheimer were also killed in action at Cedar Creek.

Company E’s Corporal Edward W. Menner and Privates Andrew Burk, John Kunker, Owen Moser, Jacob Ochs, and John Peterson were wounded in action. Kunker, Menner, Moser, Ochs, and Peterson survived but Private Burk, who had sustained gunshot wounds to the head and upper right arm and had initially been declared killed in action by mistake, was shipped from one hospital to another in an attempt to save his life. Treated first at a field hospital following the battle, he was then sent to the Union Army’s post hospital at Winchester where, on 13 December 1864, he underwent surgery to remove bone matter from his brain. He was then shipped to the Union Army’s General Hospital at Frederick, Maryland, where he died two days before Christmas (on 23 December 1864) from phthisis, a chronic wasting away from disease-related complications (often tubercular) commonly suffered by soldiers convalescing in hospitals after being severely wounded in battle.

Even Regimental Chaplain William Rodrock was placed in harm’s way, suffering a frightening near miss when a bullet pierced his cap.

Still others were captured and held as prisoners of war, a significant number of whom died. Corporal James Huff, wounded in action and captured by Confederate forces during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana just six months earlier, was captured again by Rebels during the Battle of Cedar Creek. Marched to the notorious Confederate Army prison camp at Salisbury, North Carolina, he died there as a POW on 5 March 1865. Corporal Frederick J. Scott was also captured, and died in captivity at Danville, Virginia on 22 February 1865. He was promoted to the rank of, but not mustered as a Second Lieutenant on 20 March 1865.

Corporal William H. Eichman, one of the “fortunate” ones, was wounded in action, captured, and held as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released on 11 May 1865. He was honorably mustered out less than a month later—on 1 June 1865. Privates Jacob Haggerty and Henry Beavers were also captured and held as POWs until being released on 1 March and 8 March 1865, respectively.

Private Franklin Moser was wounded in action and then also declared as missing in action following the battle.

Following these major engagements, the 47th was ordered to Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December. Private Charles Arnold was accidentally wounded on 23 November 1864, and was discharged seven months later (on 25 June 1865) on a Surgeon’s Certificate.

Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th was then ordered to outpost and railroad guarding duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia. Five days before Christmas they trudged through a snowstorm in order to reach their new home.

1865–1866

Matthew Brady’s photograph of spectators massing for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, at the side of the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Assigned in February to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah, the men of the 47th moved, via Winchester and Kernstown, back to Washington, D.C.

By 19 April 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were responsible for helping to defend the nation’s capital, following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Encamped near Fort Stevens, they received new uniforms and were resupplied.

Letters home and later newspaper interviews with survivors of the 47th Pennsylvania indicate that at least one 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while others may have guarded the Lincoln assassination conspirators during the early days of their imprisonment. As part of Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania also participated in the Union’s Grand Review on 23-24 May. Captain Levi Stuber of Company I also advanced to the rank of Major with the regiment’s central staff during this time.

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives, public domain).

On their final southern tour, First Lieutenant and Adjutant W. Scott Johnston and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians served in Savannah, Georgia from 31 May to 4 June. Assigned again to Dwight’s Division, this time they were attached to the 3rd Brigade, U.S. Department of the South. Taking over for the 165th New York Volunteers in July, they were then quartered in Charleston, South Carolina at the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury.

“Dear Madam”

One of the saddest duties First Lieutenant W. Scott Johnston performed as Regimental Adjutant during this period of his service to the nation was to communicate with the family members of deceased soldiers. In all too many cases, at this juncture in American history, bereaved widows of Union soldiers were being stonewalled in their respective quests to obtain their husbands’ pension funds from the federal government, and were forced to appeal to regimental leaders for help, as shown by this response sent sent by Johnston from the headquarters of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers at Charleston, South Carolina on 11 September 1865 to Private Uriah Keiser’s widow at her Sandy Hill, Perry County, Pennsylvania address:

Madam,

Yours of September 1st 1865, inquiring how the name of your husband appeared on the Rolls & Records of the 47th Pa Vols, addressed to Col Gobin, was this day referred by him to me for investigation and report.

In reply I would state that our Records contain the name of Uriah Keiser, 45 years of age, 5 feet 10 1/2 inches high, Dark complexion, Blue Eyes, Black hair. Born in Perry County Penna, Laborer by occupation. Enlisted Feby 22nd 1864 Harrisburg Pa. for 3 years. Mustered into service at Harrisburg Pa. Feb 22, 1864, and that he died at Barracks Hospital New Orleans La. July 1864. His final Statements and Inventory of Effects were forwarded to Brig Genl L Thomas [sp?] Adjt. Genl. U.S. Army July 5th 1865.

Uriah Keiser was never assigned to any company but carried on our Rolls and Returns as an unassigned Recruit.

Any further information you may desire, (if in my possession) will be cheerfully furnished upon application.

I am Very Respectfully Yours,

W. Scott Johnston

1st Lieut. & Adj. 47th Pa Vols

War’s End and Post-War Life

Finally, beginning on Christmas Day of 1865, First Lieutenant and Adjutant W. Scott Johnston joined the majority of men from the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in honorably mustering out at Charleston, South Carolina—a process which continued through early January. Following a stormy voyage home, the 47th Pennsylvania disembarked in New York City. The weary men were then transported to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader on 9 January 1866, the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were officially given their discharge papers.

W. Scott Johnston then returned to his pre-war career as a civil engineer. In 1870, a federal census enumerator noted that he resided in Eldora, Hardin County, Iowa while employed as an engineer.

A member of the Democratic Party, W. Scott Johnston also may have embarked on a brief political career during this time, but after placing his name on the ballot for the position of Surveyor with Hardin County, he lost to the Republican Candidate C. W. Scott, who garnered 1,252 total votes to Johnston’s 649. He tried again in 1871, but also failed in that bid to become Surveyor, losing to C.W. Scott by a margin of 1,058 to 461.

Around this same time, W. Scott Johnston was also named in a report from the first session of 43rd U.S. Congress. During its 1873-74 session, the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Military Affairs was asked to consider bill H.R. 1245 “in relation to the case of Henry D. Wharton, late commissary-sergeant Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, on application for pay of installment of bounty.” Johnston, whose title and regiment data (First Lieutenant and Adjutant 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers) were included in the report, advised the U.S. House of Representatives that Henry Wharton was honorably discharged and eligible for his back pay. (For more details, see Henry D. Wharton’s biographical sketch.)

And, sometime between 1870 and 1880, W. Scott Johnston also apparently married. Listed as a single man on the 1870 federal census, he was described by an 1880 census taker as a widower. W. Scott Johnston had also returned to New Jersey by 1880, and was residing in Phillipsburg, Warren County. From 1881-1884, he served as the Coroner of Warren County.

His entry in the 1920 edition of the General Register of the Members of the Phi Kappa Sigma Fraternity, 1850-1920 also confirms that he worked as an attorney later in life.

Final Years, Death, and Interment

Mess Hall, Mountain Branch, U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Johnson City, Tennessee (circa 1903, public domain).

Suffering from a host of health problems (arteriosclerosis, cardiac hypertrophy, chronic bronchitis, enuresis, myalgia, an old fracture of his right elbow with partial ankylosis, and rheumatism), W. Scott Johnston became so disabled toward the end of the century that he opted to move to the New Jersey Home for Disabled Soldiers in Hudson County, and was listed on the patient rolls there in 1890.

By 1900, his health improved enough to enable him to relocate to Erie County, Pennsylvania, where he was employed once again as an engineer; however, health problems began to plague him again in the new century. In 1906, he was admitted to the U.S. Home for Disabled Veterans in Dayton, Montgomery County, Ohio at the age of 73.

By 1920, he was listed on the federal census as a resident of the U.S. Home for Disabled Veterans (Mountain Branch) in Johnson City, Washington County, Tennessee. On the ledger for this home, he was described as weighing a scant 122 pounds. Sadly, this ledger also indicated that he had no family or friends. Both ledgers confirm his occupation as an engineer. Tennessee death records, including his state death certificate, confirm that he was a widower at the time of his passing.

On 11 April 1925, W. Scott Johnston finally answered his last bugle call at the Soldiers’ Home in Tennessee. His death certificate indicated that he was suffering from chronic nephritis, rheumatism and senility at the time of his passing. He was laid to rest at the Home’s cemetery on 12 April 1925.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

2. Civil War Muster Rolls, in Records of the Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs (Record Group 19, Series 19.11). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

3. Civil War Veterans’ Card File. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives, 1861-1865.

4. Death Certificate (W. Scott Johnston, file no.: 8, registered no.: 1695), in Tennessee City Death Records. Nashville, Tennessee: State of Tennessee: State Board of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics and Tennessee State Library and Archives, 1925.

5. General Register of the Members of the Phi Kappa Sigma Fraternity, 1850-1920. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Phi Kappa Sigma Fraternity, 1920.

6. “Historical Register of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers” (W. Scott Johnston; Central Branch/Dayton, Ohio; Mountain Branch/Johnson City, Tennessee). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

7. History of Hardin County Iowa Together with Sketches of Its Towns, Villages and Townships, Educational, Civil, Military and Political History; Portraits of Prominent Persons, and Biographies of Representative Citizens, pp. 367-368. Springfield, Illinois: Union Publishing Company, 1883.

8. Reports of the Committees of the House of Representatives for the First Session of the Forty-Third Congress. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Congress, 1873-1874.

9. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

10. Stegall, Joel T. “Salisbury Prison: North Carolina’s Andersonville.” Fayetteville, North Carolina: North Carolina Civil War & Reconstruction History Center, 13 September 2018.

11. U.S. Census (1850, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1920). Washington, D.C., Pennsylvania and Tennessee: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

12. U.S. and New Jersey Veterans’ Schedules (1890). Washington, D.C. and New Jersey: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

13. W. Scott Johnston, in Tennessee Deaths and Burials Index, 1874–1955. Salt Lake City, Utah: FamilySearch, 1925.

You must be logged in to post a comment.