Alternate Spellings of Surname: Harman, Herman

Copy of the 1862 Taufschein of Mary Elisabeth Herman, daughter of Private William Herman, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (U.S. Civil War Widows’ and Orphans’ Pension Files, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

William Herman (alternate surname spelling: Harman) was one of the entirely-too-many Pennsylvanians who became “unknown soldiers” when their burial locations went undocumented by army clerks overwhelmed by the sheer number of casualties they were expected to process during the later years of the American Civil War. Known to have had family ties to Berks and Lehigh counties, he might very well have chosen not to head off to war had he known what would happen to him—or what would ultimately happen to his wife and children.

But, then again, he might still have felt the desire to serve his country. Based on post-war attestations by his friends and neighbors, he was proud to be a soldier in the Union Army.

Formative Years

Born circa 1834, William Herman was employed as a servant in the Hynemansville, Lehigh County home of the Kramlich family circa 1855-1857, according to testimony provided in 1868 by the Kramlichs’ son, Charles H. Kramlich. But sometime during the latter period of that job, he opted to take his life in an entirely new direction—by beginning a family of his own.

Choosing to court Caroline Miller (1830-1895; alternate given name: Carolina), who was a daughter of Daniel Miller, Sr. and Catharine (Welder) Miller, William Herman married Caroline in Kutztown, Berks County, Pennsylvania on 28 September 1857. Their wedding ceremony was performed by Justice of the Peace James M. Geehr.

They soon welcomed the birth of a son, Jonathan M. Herman, who arrived on 12 June 1857. Their child was delivered by Edward Hottenstein, M.D., who later submitted a legal affidavit confirming Jonathan’s exact date of birth.

By 1860, William Herman was employed as a laborer and was living with Caroline and Jonathan in Seiberlingsville, Weisenberg Township, Lehigh County. Their neighbors were wealthy merchant Joshua Seiberling and William’s fellow laborer, Henry Brunner, who would later witness the baptism of the Herman’s second child.

That child, Mary Elisabeth Herman, was born in Weisenberg Township, Lehigh County on 12 July 1861. Baptized by the Rev. Alfred Herman on 25 July of that same year, she was also known to family and friends as “Lizzy.”

* Note: In an affidavit filed by Meno A. Smith, a resident of Hynemansville in Lehigh County, which was submitted to the court overseeing the affairs of Caroline (Miller) Harman in 1866, Smith attested that he had been “intimately acquainted with William Harman” during this time and was also “acquainted with Caroline Harman his widow and their children Jonathan and Elizabeth Harman.” He then affirmed that “Jonathan was … a legitimate child of said William and Caroline Harman, and [he] always treated said child as such.”

He further explained that “William and Caroline Harman cohabited together before this child Jonathan was born,” and that “William Harman made no distinction between the two children Jonathan and M. Elizabeth—and heard said William often declare this (meaning Jonathan) is my child that in every conversation with the said William he acknowledged said Jonathan as his child—and that never was there a doubt or suspicion expressed or entertained … as to the illegitimacy of said child Jonathan.”

Civil War

Despite having young children, William Herman became one of Pennsylvania’s early responders to President Abraham Lincoln’s calls for volunteers to help bring a swift end to the American Civil War. After enrolling for military service in Catasauqua, Pennsylvania on 21 August 1861, he officially mustered in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg on 30 August as a private with Company F of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Military records at the time indicated that he was a twenty-eight-year-old laborer from Catasauqua, who was five feet, six inches tall with brown hair, gray eyes and a light complexion.

* Note: Company F of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was the first company of this Union regiment to muster in for duty. The initial recruitment for members to staff this unit was conducted in Catasauqua, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania by Henry Samuel Harte, a native of Darmstadt, Grand Duchy of Hesse (now Darmstadt, Hesse, Germany) who had become a naturalized American citizen in 1851, had been appointed captain of the Lehigh County militia unit known as the Catasauqua Rifles during the late 1850s and was then commissioned as captain of Company F of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the fateful summer of 1861.

Following a brief training period in light infantry tactics at Camp Curtin, the soldiers of Company F and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were transported south by rail to Washington, D.C. Stationed roughly two miles from the White House, they pitched their tents at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown beginning 21 September. Henry D. Wharton, a musician from the regiment’s C Company, penned an update the next day to the Sunbury American, his hometown newspaper:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope for an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

While at Camp Kalorama, Captain Harte issued his first directive (Company Order No. 1), that his company drill four times per day, each time for one hour.

On 24 September, the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry finally became part of the United States Army when its men were officially mustered into federal service. On 27 September—a rainy day, the 47th Pennsylvania was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania was on the move again.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the 47th Pennsylvanians marched behind their regimental band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (one hundred and sixty-five steps per minute using thirty-three-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). Having completed a roughly eight-mile trek, they were now situated near the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (nicknamed “Baldy”), the commander of the Union’s massive U.S. Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Armed with Mississippi rifles supplied by the Keystone State, their job was to prevent attacks by the Confederate States Army on the nation’s capital.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

The Big Chestnut Tree, Camp Griffin, Langley, Virginia, 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” in reference to the large chestnut tree located within their camp’s boundaries. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly ten miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a mid-October letter home, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin (the leader of C Company who would be promoted in 1864 to lead the entire 47th Regiment) reported that companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left-wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops. In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th engaged in a Divisional Review, described by Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” Less than a month later, in his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review that was overseen by the regiment’s founder and commanding officer, Colonel Tilghman H. Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward for their performance—and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained brand new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

1862

The City of Richmond, a sidewheel steamer which transported Union troops during the Civil War (Maine, circa late 1860s, public domain).

Next ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were transported by rail to Alexandria, Virginia, where they boarded the steamship City of Richmond, and sailed the Potomac to the Washington Arsenal. Reequipped there, they were then marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C.

The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the United States Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship U.S. Oriental.

Alfred Waud’s 1862 sketch of Fort Taylor and Key West, Florida (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamers on Monday, 27 January, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers commenced boarding the Oriental for the final time, with the officers boarding last. Then, at 4 p.m., per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, they steamed away for the Deep South. They were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Fort Taylor (Key West) and Fort Jefferson (Dry Tortugas).

Private William Herman and the other members of Company F arrived in Key West in early February 1862, and were assigned with their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to garrison Fort Taylor. During the weekend of Friday, 14 February, the 47th Pennsylvanians introduced their presence to Key West residents as the regiment paraded through the streets of the city. That Sunday, soldiers from the 47th Pennsylvania also mingled with locals by attending services at area churches.

Drilling daily in heavy artillery tactics, they also strengthened the fortifications at this federal installation. On 1 April 1862, Sergeant Augustus Eagle was promoted to the rank of second lieutenant.

In addition to their exhausting military duties, the 47th Pennsylvanians also encountered a persistent and formidable foe—disease. Several members of the regiment fell ill, largely due to poor sanitary conditions and water quality. As a result, multiple members of the regiment were discharged on surgeons’ certificates of disability and Second Lieutenant Henry H. Bush and Private Edward Bartholomew died at Fort Taylor, respectively, on 31 March and 3 April.

But there were lighter moments as well.

According to a letter penned by Henry Wharton on 27 February 1862, the regiment commemorated the birthday of former U.S. President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation (first delivered in 1796), the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February.

The festivities resumed two days later when the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards.” This was then followed by a concert by the Regimental Band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

Per Schmidt, 4 June 1862 was also a festive day for the regiment. As the USS Niagara sailed for Boston after transferring its responsibilities as the flagship of the Union Navy squadron in that sector to the USS Potomac, the guns of fifteen warships anchored nearby fired a salute, as did the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Captain Harte and F Company played a prominent role in the day’s events as they “fired 15 of the heavy casemate guns from Fort Taylor at 4 PM.”

This 1856 map of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad shows the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina in relation to the towns of Beaufort and Pocotaligo (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina from mid-June through July, the 47th Pennsylvanians camped near Fort Walker before relocating to the Beaufort District in the U.S. Army’s Department of the South, roughly thirty-five miles away. Frequently assigned to hazardous picket detail north of their main camp, which put them at increased risk from enemy sniper fire, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania became known for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” and “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan,” according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

During the second week of July, according to Schmidt, Major William H. Gausler and Captain Henry S. Harte returned home to the Lehigh Valley to resume their recruiting efforts. After arriving in Allentown on 15 July, they quickly re-established an efficient operation, which they would keep running through early November 1862. During this time, Major Gausler was able to persuade fifty-four new recruits to join the 47th Pennsylvania while Harte rounded up an additional twelve.

Meanwhile, back in the Deep South, Captain Harte’s F Company men were commanded by Harte’s direct subordinates, First Lieutenant George W. Fuller and Second Lieutenant August G. Eagle.

On 12 September, Colonel Tilghman Good and his adjutant, First Lieutenant Washington H. R. Hangen, issued Regimental Order No. 207 from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Headquarters in Beaufort, South Carolina:

I. The Colonel commanding desires to call the attention of all officers and men in the regiment to the paramount necessity of observing rules for the preservation of health. There is less to be apprehended from battle than disease. The records of all companies in climate like this show many more casualties by the neglect of sanitary post action then [sic] by the skill, ordnance and courage of the enemy. Anxious that the men in my command may be preserved in the full enjoyment of health to the service of the Union. And that only those who can leave behind the proud epitaph of having fallen on the field of battle in the defense of their country shall fail to return to their families and relations at the termination of this war.

II. All the tents will be struck at 7:30 a.m. on Monday, Wednesday and Saturday of each week. The signal for this purpose will be given by the drum major by giving three taps on the drum. Every article of clothing and bedding will be taken out and aired; the flooring and bunks will be thoroughly cleaned. By the same signal at 11 a.m. the tents will be re-erected. On the days the tents are not struck the sides will be raised during the day for the purpose of ventilation.

III. The proper cooking of provisions is a matter of great importance more especially in this climate but have not yet received from a majority of officers of the regiment that attention that should be paid to it.

IV. Thereafter an officer of each company will be detailed by the commander of each company and have their names reported to these headquarters to superintend the cooking of provisions taking care that all food prepared for the soldiers is sufficiently cooked and that the meats are all boiled or seared (not fried). He will also have charge of the dress table and he is held responsible for the cleanliness of the kitchen cooking utensils and the preparation of the meals at the time appointed.

V. The following rules for the taking of meals and regulations in regard to the conducting of the company will be strictly followed. Every soldier will turn his plate, cup, knife and fork into the Quarter Master Sgt who will designate a permanent place or spot for each member of the company and there leave his plate & cup, knife and fork placed at each meal with the soldier’s rations on it. Nor will any soldier be permitted to go to the company kitchen and take away food therefrom.

VI. Until further orders the following times for taking meals will be followed Breakfast at six, dinner at twelve, supper at six. The drum major will beat a designated call fifteen minutes before the specified time which will be the signal to prepare the tables, and at the time specified for the taking of meals he will beat the dinner call. The soldier will be permitted to take his spot at the table before the last call.

VII. Commanders of companies will see that this order is entered in their company order book and that it is read forth with each day on the company parade. All commanding officers of companies will regulate daily their time by the time of this headquarters. They will send their 1st Sergeants to this headquarters daily at 8 a.m. for this purpose.

Great punctuality is enjoined in conforming to the stated hours prescribed by the roll calls, parades, drills, and taking of meals; review of army regulations while attending all roll calls to be suspended by a commissioned officer of the companies, and a Captain to report the alternate to the Colonel or the commanding officer.

At 5 a.m., Commanders of companies are imperatively instructed to have the company quarters washed and policed and secured immediately after breakfast.

At 6 a.m., morning reports of companies request [sic] by the Captains and 1st Sgts and all applications for special privileges of soldiers must be handed to the Adjutant before 8 a.m.

By Command of Col. T. H. Good

W. H. R. Hangen Adj

In addition, First Lieutenant and Regimental Adjutant Hangen clarified the regiment’s schedule as follows:

- Reveille (5:30 a.m.) and Breakfast (6:00 a.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Guard (6:10 a.m. and 6:15 a.m.)

- Surgeon’s Call (6:30 a.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Company Drill (6:45 a.m. and 7:00 a.m.)

- Recall from Company Drill (8:00 a.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Squad Drill (9:00 a.m. and 9:15 a.m.)

- Recall from Squad Drill (10:30 a.m.) and Dinner (12:00 noon)

- Call for Non-commissioned Officers (1:30 p.m.)

- Recall for Non-commissioned Officers (2:30 p.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Squad Drills (3:15 p.m. and 3:30 p.m.)

- Recall from Squad Drill (4:30 p.m.)

- First and Second Calls for Dress Parade (5:10 p.m. and 5:15 p.m.)

- Supper (6:10 p.m.)

- Tattoo (9:00 p.m.) and Taps (9:15 p.m.)

First State Color, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (presented to the regiment by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin, 20 September 1861; retired 11 May 1865, public domain).

As the one-year anniversary of the 47th Pennsylvania’s departure from the Great Keystone State dawned on 20 September, thoughts turned to home and Divine Providence as Colonel Tilghman Good issued Special Order No. 60 from the 47th’s Regimental Headquarters in Beaufort, South Carolina:

The Colonel commanding takes great pleasure in complimenting the officers and men of the regiment on the favorable auspices of today.

Just one year ago today, the organization of the regiment was completed to enter into the service of our beloved country, to uphold the same flag under which our forefathers fought, bled, and died, and perpetuate the same free institutions which they handed down to us unimpaired.

It is becoming therefore for us to rejoice on this first anniversary of our regimental history and to show forth devout gratitude to God for this special guardianship over us.

Whilst many other regiments who swelled the ranks of the Union Army even at a later date than the 47th have since been greatly reduced by sickness or almost cut to pieces on the field of battle, we as yet have an entire regiment and have lost but comparatively few out of our ranks.

Certain it is we have never evaded or shrunk from duty or danger, on the contrary, we have been ever anxious and ready to occupy any fort, or assume any position assigned to us in the great battle for the constitution and the Union.

We have braved the danger of land and sea, climate and disease, for our glorious cause, and it is with no ordinary degree of pleasure that the Colonel compliments the officers of the regiment for the faithfulness at their respective posts of duty and their uniform and gentlemanly manner towards one another.

Whilst in numerous other regiments there has been more or less jammings and quarrelling [sic] among the officers who thus have brought reproach upon themselves and their regiments, we have had none of this, and everything has moved along smoothly and harmoniously. We also compliment the men in the ranks for their soldierly bearing, efficiency in drill, and tidy and cleanly appearance, and if at any time it has seemed to be harsh and rigid in discipline, let the men ponder for a moment and they will see for themselves that it has been for their own good.

To the enforcement of law and order and discipline it is due our far fame as a regiment and the reputation we have won throughout the land.

With you he has shared the same trials and encountered the same dangers. We have mutually suffered from the same cold in Virginia and burned by the same southern sun in Florida and South Carolina, and he assures the officers and men of the regiment that as long as the present war continues, and the service of the regiment is required, so long he stands by them through storm and sunshine, sharing the same danger and awaiting the same glory.

A Regiment Victorious — and Bloodied

Earthworks surrounding the Confederate battery on Saint John’s Bluff above the Saint John’s River in Florida (J. H. Schell, 1862, public domain).

During a return expedition to Florida beginning 30 September, the 47th joined with the 1st Connecticut Battery, 7th Connecticut Infantry, and part of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in assaulting Confederate forces at their heavily protected camp at Saint John’s Bluff, overlooking the Saint John’s River area. Trekking and skirmishing through roughly twenty-five miles of dense swampland and forests after disembarking from ships at Mayport Mills on 1 October, the 47th captured artillery and ammunition stores (on 3 October) that had been abandoned by Confederate forces during the bluff’s bombardment by Union gunboats.

The capture of Saint John’s Bluff followed a string of U.S. Army and Navy successes which enabled the Union to gain control over key southern towns and transportation hubs. In November 1861, the Union’s South Atlantic Blockading Squadron had established an operations base at Port Royal, South Carolina, facilitating Union expeditions to Georgia and Florida, during which U.S. troops were able to take possession of Fort Clinch and Fernandina, Florida (3-4 March 1862), secure the surrender of Fort Marion and Saint Augustine (11 March) and establish a Union Navy base at Mayport Mills (mid-March). That summer, Brigadier-General Joseph Finnegan, commanding officer of the Confederate States of America’s Department of Middle and Eastern Florida, ordered the placement of earthworks-fortified gun batteries atop Saint John’s Bluff and at Yellow Bluff nearby. Confederate leaders hoped to disable the Union’s naval and ground force operations at and beyond Mayport Mills with as many as eighteen cannon, including three eight-inch siege howitzers and eight-inch smoothbores and Columbiads (two of each).

After the U.S. gunboats Uncas and Patroon exchanged shell fire with the Confederate battery at Saint John’s Bluff on 11 September, Rebel troops were initially driven away, but then returned to the bluff. When a second, larger Union gunboat flotilla tried and failed again six days later to shake the Confederates loose, Union military leaders ordered an army operation with naval support.

Backed by U.S. gunboats Cimarron, E. B. Hale, Paul Jones, Uncas, and Water Witch that were armed with twelve-pound boat howitzers, the 1,500-strong Union Army force of Brigadier-General Brannan moved up the Saint John’s River and further inland along the Pablo and Mt. Pleasant Creeks on 1 October 1862 before disembarking and marching for Saint John’s Bluff. When the 47th Pennsylvanians reached Saint John’s Bluff with their fellow Union brigade members on 3 October 1862, they found the battery abandoned. (Other Union troops discovered that the Yellow Bluff battery was also Rebel free.)

According to Henry Wharton, “On the day following our occupation of these works the guns were dismounted and removed on board the steamer Neptune, together with the shot and shell, and removed to Hilton Head. The powder was all used in destroying the batteries.”

Meanwhile that same weekend (Friday and Saturday, 3-4 October 1862), Brigadier-General Brannan, who was quartered on board the Ben Deford as the Union expedition’s commanding officer, was busy penning reports to his superiors while also planning the next move of his expeditionary force. That Saturday, Brannan chose several officers to direct their subordinates to prepare rations and ammunition for a new foray that would take them roughly twenty miles upriver to Jacksonville. (A sophisticated hub of cultural and commercial activities with a racially diverse population of more than two thousand residents, the city had repeatedly changed hands between the Union and Confederacy until its occupation by Union forces on 12 March 1862.) Among the Union soldiers selected for this mission were 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers from Company C, Company E and Company K.

One of the first groups to depart—Company C of the 47th Pennsylvania—did so that Saturday as part of a small force made up of infantry and gunboats, the latter of which were commanded by Captain Charles E. Steedman. Their mission was to destroy all enemy boats they encountered to stop the movement of Confederate troops throughout the region. Upon arrival in Jacksonville later that same day, the infantrymen were charged by Brannan with setting fire to the office of that city’s Southern Rights newspaper. Before that action was taken, however, Captain Gobin and his subordinate, Henry Wharton, who had both been employed by the Sunbury American newspaper in Sunbury, Pennsylvania prior to the war, salvaged the pro-Confederacy publication’s printing press so that Wharton could more efficiently produce the regimental newspaper he had launched while the 47th Pennsylvania was stationed at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida.

On Sunday, 5 October, Brannan and his detachment sailed away for Jacksonville at 6:30 a.m. Per Wharton, the weekend’s events unfolded as follows:

As soon as we had got possession of the Bluff, Capt. Steedman and his gunboats went to Jacksonville for the purpose of destroying all boats and intercepting the passage of the rebel troops across the river, and on the 5th Gen. Brannan also went up to Jacksonville in the steamer Ben Deford, with a force of 785 infantry, and occupied the town. On either side of the river were considerable crops of grain, which would have been destroyed or removed, but this was found impracticable for want of means of transportation. At Yellow Bluff we found that the rebels had a position in readiness to secure seven heavy guns, which they appeared to have lately evacuated, Jacksonville we found to be nearly deserted, there being only a few old men, women, and children in the town, soon after our arrival, however, while establishing our picket line, a few cavalry appeared on the outskirts, but they quickly left again. The few inhabitants were in a wretched condition, almost destitute of food, and Gen. Brannan, at their request, brought a large number up to Hilton Head to save them from starvation, together with 276 negroes—men, women, and children, who had sought our protection.

Receiving word soon after his arrival at Jacksonville that “Rebel steamers were secreted in the creeks up the river,” Brigadier-General Brannan ordered Captain Charles Yard of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Company E to take a detachment of one hundred men from his own company and those of the 47th’s Company K, and board the steamer Darlington “with two 24-pounder light howitzers and a crew of 25 men.” All would be under the command of Lieutenant Williams of the U.S. Navy, who would order the “convoy of gunboats to cut them out.”

According to Brigadier-General Brannan, the Union party “returned on the morning of the 9th with a Rebel steamer, Governor Milton, which they captured in a creek about 230 miles up the river and about 27 miles north [and slightly west] from the town of Enterprise.… On the return of the successful expedition after the Rebel steamers … I proceeded with that portion of my command to St. John’s Bluff, awaiting the return of the Boston.”

In his report on the matter, filed from Mount Pleasant Landing, Florida on 2 October 1862, Colonel Tilghman H. Good described the Union Army’s assault on Saint John’s Bluff:

In accordance with orders received I landed my regiment on the bank of Buckhorn Creek at 7 o’clock yesterday morning. After landing I moved forward in the direction of Parkers plantation, about 1 mile, being then within about 14 miles of said plantation. Here I halted to await the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut Regiment. I advanced two companies of skirmishers toward the house, with instructions to halt in case of meeting any of the enemy and report the fact to me. After they had advanced about three-quarters of a mile they halted and reported some of the enemy ahead. I immediately went forward to the line and saw some 5 or 6 mounted men about 700 or 800 yards ahead. I then ascended a tree, so that I might have a distinct view of the house and from this elevated position I distinctly saw one company of infantry of infantry close by the house, which I supposed to number about 30 or 40 men, and also some 60 or 70 mounted men. After waiting for the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut Volunteers until 10 o’clock, and it not appearing, I dispatched a squad of men back to the landing for a 6-pounder field howitzer which had been kindly offered to my service by Lieutenant Boutelle, of the Paul Jones. This howitzer had been stationed on a flat-boat to protect our landing. The party, however, did not arrive with the piece until 12 o’clock, in consequence of the difficulty of dragging it through the swamp. Being anxious to have as little delay as possible, I did not await the arrival of the howitzer, but at 11 a.m. moved forward, and as I advanced the enemy fled.

After reaching the house I awaited the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut and the howitzer. After they arrived I moved forward to the head of Mount Pleasant Creek to a bridge, at which place I arrived at 2 p.m. Here I found the bridge destroyed, but which I had repaired in a short time. I then crossed it and moved down on the south bank toward Mount Pleasant Landing. After moving about 1 mile down the bank of the creek my skirmishing companies came upon a camp, which evidently had been very hastily evacuated, from the fact that the occupants had left a table standing with a sumptuous meal already prepared for eating. On the center of the table was placed a fine, large meat pie still warm, from which one of the party had already served his plate. The skirmishers also saw 3 mounted men leave the place in hot haste. I also found a small quantity of commissary and quartermasters stores, with 23 tents, which, for want of transportation, I was obliged to destroy. After moving about a mile farther on I came across another camp, which also indicated the same sudden evacuation. In it I found the following articles … breech-loading carbines, 12 double-barreled shot-guns, 8 breech-loading Maynard rifles, 11 Enfield rifles, and 96 knapsacks. These articles I brought along by having the men carry them. There were, besides, a small quantity of commissary and quartermasters stores, including 16 tents, which, for the same reason as stated, I ordered to be destroyed. I then pushed forward to the landing, where I arrived at 7 p.m.

We drove the enemys [sic] skirmishers in small parties along the entire march. The march was a difficult one, in consequence of meeting so many swamps almost knee-deep.

Integration of the Regiment

On 5 and 15 October 1862, respectively, the 47th Pennsylvania made history as it became an integrated regiment, adding to its muster rolls several Black men who had escaped chattel enslavement from plantations near Beaufort, South Carolina. Among the formerly enslaved men who enlisted at this time were Bristor Gethers, Abraham Jassum and Edward Jassum.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army’s map of the Pocotaligo-Coosawhatchie Expedition, South Carolina, October 22, 1862. Blue Arrow: Mackay’s Point, where the U.S. Tenth Army debarked and began its march. Blue Box: Position of Union troops (blue) and Confederate troops (red) in relation to the Pocotaligo bridge and town of Pocotaligo, the Charleston & Savannah Railroad, and the Caston and Frampton plantations (blue highlighting added by Laurie Snyder, 2023; public domain; click to enlarge).

From 21-23 October 1862, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel T. H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers next engaged the heavily protected Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina—including at Frampton’s Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge—a key piece of southern railroad infrastructure that Union leaders had ordered to be destroyed in order to disrupt the flow of Confederate troops and supplies in the region.

Harried by snipers en route to the Pocotaligo Bridge, they met resistance from an entrenched, heavily fortified Confederate battery which opened fire on the Union troops as they entered an open cotton field. Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests. The Union soldiers grappled with Confederates where they found them, pursuing the Rebels for four miles as they retreated to the bridge. There, the 47th relieved the 7th Connecticut. But the enemy was just too well armed. After two hours of intense fighting in an attempt to take the ravine and bridge, depleted ammunition forced the 47th to withdraw to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th Pennsylvania were significant. Two officers and eighteen enlisted men died; an additional two officers and one hundred and fourteen enlisted were wounded.

Following their return to Hilton Head, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers recuperated from their wounds and resumed their normal duties. In short order, several members of the 47th were called upon to serve as the funeral honor guard for Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, and given the high honor of firing the salute over this grave. (Commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South, Mitchel succumbed to yellow fever on 30 October 1862. The Mountains of Mitchel, a part of Mars’ South Pole discovered in 1846 by Mitchel as a University of Cincinnati astronomer, and Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, were both named after him.)

Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, much of 1863 would be spent garrisoning federal installations in Florida as part of the 10th Corps, U.S. Department of the South. Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I would once again garrison Fort Taylor in Key West, but this time, the men from Companies D, F, H, and K, including Private William Herman, would garrison Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the southern coast of Florida.

After packing their belongings at their Beaufort, South Carolina encampment and loading their equipment onto the U.S. Steamer Cosmopolitan, the officers and enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry sailed toward the mouth of the Broad River on 15 December 1862, and anchored briefly at Port Royal Harbor in order to allow the regiment’s medical director, Elisha W. Baily, M.D., and members of the regiment who had recuperated enough from their Pocotaligo-related battle injuries at the Union’s General Hospital at Hilton Head, to rejoin the regiment.

At 5 p.m. that same evening, the regiment sailed for Florida, during what was later described by several members of the regiment as a treacherous and nerve-wracking voyage. According to Schmidt, the ship’s captain “steered a course along the coast of Florida for most of the voyage,” which made the voyage more precarious “because of all the reefs.” On 16 December “the second night, the ship was jarred as it ran aground on one during a storm, but broke free, and finally steered a course further from shore, out in the Gulf Stream.”

In a letter penned to the Sunbury American on 21 December, Henry Wharton provided the following details about the regiment’s trip:

On the passage down, we ran along almost the whole coast of Florida. Rather a dangerous ground, and the reefs are no playthings. We were jarred considerably by running on one, and not liking the sensation our course was altered for the Gulf Stream. We had heavy sea all the time. I had often heard of ‘waves as big as a house,’ and thought it was a sailor’s yarn, but I have seen ‘em and am perfectly satisfied; so now, not having a nautical turn of mind, I prefer our movements being done on terra firma, and leave old neptune to those who have more desire for his better acquaintance. A nearer chance of a shipwreck never took place than ours, and it was only through Providence that we were saved. The Cosmopolitan is a good river boat, but to send her to sea, loadened [sic, loaded] with U.S. troops is a shame, and looks as though those in authority wish to get clear of soldiers in another way than that of battle. There was some sea sickness on our passage; several of the boys ‘casting up their accounts’ on the wrong side of the ledger.

According to Corporal George Nichols of Company E, “When we got to Key West the Steamer had Six foot of water in her hole [sic]. Waves Mountain High and nothing but an old river Steamer. With Eleven hundred Men on I looked for her to go to the Bottom Every Minute.”

Although the Cosmopolitan arrived at the Key West Harbor on Thursday, 18 December, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers did not set foot on Florida soil until noon the next day. The men from Companies C and I were immediately marched to Fort Taylor, where they were placed under the command of Major William Gausler, the regiment’s third-in-command. The men from Companies B and E were assigned to the older barracks that had been erected by the United States Army, and were placed under the command of B Company Captain Emanuel P. Rhoads while the men from Companies A and G were placed under the command of A Company Captain Richard A. Graeffe, and stationed at newer facilities known as the “Lighthouse Barracks” on “Lighthouse Key.”

Three days later, on Saturday, 21 December, Lieutenant-Colonel G. W. Alexander, the regiment’s second-in-command, sailed away aboard the Cosmopolitan with the men from the regiment’s remaining companies—Companies D, F, H, and K—and headed south to Fort Jefferson, where they would assume garrison duties at the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas, roughly seventy miles off the coast of Florida (in the Gulf of Mexico). According to Henry Wharton:

We landed here on last Thursday at noon, and immediately marched to quarters. Company I. and C., in Fort Taylor, E. and B. in the old Barracks, and A. and G. in the new Barracks. Lieut. Col. Alexander, with the other four companies proceeded to Tortugas, Col. Good having command of all the forces in and around Key West. Our regiment relieves the 90th Regiment N.Y.S. Vols. Col. Joseph Morgan, who will proceed to Hilton Head to report to the General commanding. His actions have been severely criticized by the people, but, as it is in bad taste to say anything against ones [sic, one’s] superiors, I merely mention, judging from the expression of the citizens, they were very glad of the return of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers….

Key West has improved very little since we left last June, but there is one improvement for which the 90th New York deserve a great deal of praise, and that is the beautifying of the ‘home’ of dec’d. soldiers. A neat and strong wall of stone encloses the yard, the ground is laid off in squares, all the graves are flat and are nicely put in proper shape by boards eight or ten inches high on the ends sides, covered with white sand, while a head and foot board, with the full name, company and regiment, marks the last resting place of the patriot who sacrificed himself for his country….

1863

Fort Jefferson’s moat and wall, circa 1934, Dry Tortugas, Florida (C.E. Peterson, Library of Congress; public domain).

Although water quality was a challenge for members of the regiment at both of their Florida duty stations, it was particularly problematic for Private William Herman and the other 47th Pennsylvanians who were stationed at Fort Jefferson. According to Schmidt:

‘Fresh’ water was provided by channeling the rains from the fort’s barbette through channels in the interior walls, to filter trays filled with sand; and finally to the 114 cisterns located under the fort which held 1,231,200 gallons of water. The cisterns were accessible in each of the first level cells or rooms through a ‘trap hole’ in the floor covered by a temporary wooden cover…. Considerable dirt must have found its way into these access points and was responsible for some of the problems resulting in the water’s impurity…. The fort began to settle and the asphalt covering on the outer walls began to deteriorate and allow the sea water (polluted by debris in the moat) to penetrate the system…. Two steam condensers were available … and distilled 7000 gallons of tepid water per day for a separate system of reservoirs located in the northern section of the parade ground near the officers [sic, officers’] quarters. No provisions were made to use any of this water for personal hygiene of the [planned 1,500-soldier garrison force]….

As a result, the soldiers stationed there washed themselves and their clothes, using saltwater from the ocean. As if that weren’t difficult enough, “toilet facilities were located outside of the fort,” according to Schmidt:

At least one location was near the wharf and sallyport, and another was reached through a door-sized hole in a gunport, and a walk across the moat on planks at the northwest wall…. These toilets were flushed twice each day by the actions of the tides, a procedure that did not work very well and contributed to the spread of disease. It was intended that the tidal flush should move the wastes into the moat, and from there, by similar tidal action, into the sea. But since the moat surrounding the fort was used clandestinely by the troops to dispose of litter and other wastes … it was a continuous problem for Lt. Col. Alexander and his surgeon.

As for daily operations in the Dry Tortugas, there was a fort post office and the “interior parade grounds, with numerous trees and shrubs in evidence, contained … officers quarters, [a] magazine, kitchens and out houses,” according to Schmidt, as well as “a ‘hot shot oven’ which was completed in 1863 and used to heat shot before firing.”

Most quarters for the garrison … were established in wooden sheds and tents inside the parade [grounds] or inside the walls of the fort in second-tier gun rooms of ‘East’ front no. 2, and adjacent bastions … with prisoners housed in isolated sections of the first and second tiers of the southeast, or no. 3 front, and bastions C and D, located in the general area of the sallyport. The bakery was located in the lower tier of the northwest bastion ‘F’, located near the central kitchen….

Additional Duties: Diminishing Florida’s Role as the “Supplier of the Confederacy”

On top of the strategic role played by the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers in preventing foreign powers from assisting the Confederate Army and Navy in gaining control over federal forts in the Deep South, members of this regiment would also be called upon to play an ongoing role in weakening Florida’s abilities to supply and transport food and troops throughout the area held by the Confederate States of America.

Prior to intervention by Union Army and Navy forces, the owners of plantations and livestock ranches, as well as the operators of small, family farms across Florida, had been able to consistently furnish beef and pork, fish, fruits, and vegetables to Confederate troops stationed throughout the Deep South during the first year of the American Civil War. Large herds of cattle were raised near Fort Myers, for example, while orchard owners in the Saint John’s River area were actively engaged in cultivating large orange groves (while other types of citrus trees were easily found growing throughout the state’s wilderness areas).

The state was also a major producer of salt, which was used as a preservative for the foods. As a result, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and other Union troops across Florida were ordered to capture or destroy salt manufacturing facilities in order to further curtail the enemy’s access to food.

And they would be undertaking all of these duties in conditions that were far more challenging than what many other Union Army units were experiencing up north in the Eastern Theater. The weather was frequently hot and humid as spring turned to summer, the mosquitos and other insects were an ever-present annoyance and serious threat when they were carrying tropical diseases, and there were also scorpions and snakes that put the men’s health at further risk.

Despite all of these hardships, when members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were offered the opportunity to re-enlist, more than half chose to do so, knowing full well that the fight to preserve America’s Union was not yet over. Among those signing up again was Private William Herman who re-enrolled with the 47th Pennsylvania’s F Company at Fort Jefferson on 19 October 1863. Awarded the coveted title of “Veteran Volunteer,” as well as a veteran’s furlough as a reward for his reenlistment, Private Herman returned home to Pennsylvania, where he “ordered a fine supper at Ettinger’s Hotel, in said Hynemansville, for his wife Caroline and his two children Jonathan and M. Elizabeth, and afterwards brought them there,” according to testimony given in 1868 by Charles H. Kramlich. This was done just before he left again for the army.”

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to expand the Union Army’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858 following the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. Per orders issued earlier in 1864 by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, that the fort be used to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade, Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of men from Company A were charged with expanding the fort and conducting raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. Graeffe and his men subsequently turned the fort into both their base of operations and a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate Army deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops.

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost-fully-reunited regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps (XIX Corps), and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of two hundred and forty-five Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria, Louisiana with those prisoners on 9 April.)

Red River Campaign

Natchitoches, Louisiana (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 7 May 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The early days on the ground in Louisiana quickly woke the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers up to just how grueling this new phase of duty would be. From 14-26 March, most members of the regiment marched for the towns of Alexandria and Natchitoches, near the top of the L-shaped state, passing through New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington.

From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James Bullard, John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were then officially mustered in for duty on 22 June at Morganza. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “(Colored) Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long harsh-climate trek through enemy territory, the 47th Pennsylvania encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill (now the Village of Pleasant Hill) the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day.

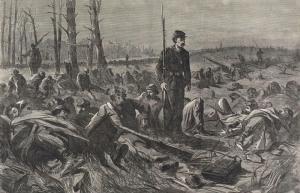

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, sixty members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the intense volley of fire unleashed during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield because of its proximity to the community of Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

During this engagement, the 47th Pennsylvania succeeded in recapturing a Massachusetts artillery battery lost during the earlier Confederate assault. Unfortunately, the regiment’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander, was nearly killed during the fight that day, and Color-Sergeant Benjamin Walls was shot in the left shoulder while mounting the 47th Pennsylvania’s colors on one of the recaptured caissons. Sergeant William Pyers was then also wounded while grabbing the American flag from Walls as he fell to prevent it from falling into enemy hands.

Alexander, Walls and Pyers all survived the day and continued to fight on with the 47th, but many others were killed in action or wounded so severely that they were unable to continue their service with the 47th. Still others from the 47th were captured by Confederate troops, marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as prisoners of war until they were released during prisoner exchanges that began in July and continued through November. At least two members of the 47th Pennsylvania never made it out of there alive. Private Samuel Kern of Company D died there on 12 June 1864, and Private John Weiss of F Company, who had been wounded in action at Pleasant Hill, died from those wounds on 15 July.

Meanwhile, as the captured 47th Pennsylvanians were being spirited away to Texas, the bulk of the regiment was carrying out orders from senior Union Army leaders to head for Grand Ecore, Louisiana. Encamped there from 11 April t0 22 April 1864, they engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications.

They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April. While en route, they were attacked again—this time at the rear of their retreating brigade, but were able to quickly end the encounter and continue on to reach Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night—after a forty-five-mile march.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April 1864), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Union Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on the Confederate cavalry of Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”).

Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s twenty-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops situated near a bayou and on a bluff, Brigadier-General Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending the other two brigades to find a safe spot where his Union troops could ford the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, other troops serving with Emory’s brigade attacked Bee’s flank to force a Rebel retreat, and then erected a series of pontoon bridges that enabled the 47th and other remaining Union soldiers to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. In a letter penned from Morganza, Louisiana on 29 May, Henry Wharton described what had happened to the 47th Pennsylvanians during and immediately after making camp at Grand Ecore:

Our sojourn at Grand Ecore was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one on the boys, for by ten o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty-five miles. On that day the rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns, opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebel prisoners say it ‘seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth of this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton of Western Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to the Union officer who oversaw its construction, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, they learned they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned yet again to the hard labor of fortification work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that enabled Union gunboats to more easily make their way back down the Red River. According to Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river. After a great deal labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits [sic] on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Continuing their march, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed toward Avoyelles Parish. According to Wharton:

On Sunday, May 15, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad wherewith the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired and we advanced ‘till dark, when the forces halted for the night, with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

Having entered Avoyelles Parish, they “rested on their arms” for the night, half-dozing without pitching their tents, but with their rifles right beside them. They were now positioned just outside of Marksville, Louisiana on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, the infantry advanced in line until they reached Mousoula [sic], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of our army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Continuing on, the surviving members of the 47th marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. According to Wharton, the members of Company C were sent on a special mission which took them on an intense one-hundred-and-twenty-mile journey:

Company C, on last Saturday was detailed by the General in command of the Division to take one hundred and eighty-seven prisoners (rebs) to New Orleans. This they done [sic] satisfactorily and returned yesterday to their regiment, ready for duty.

While encamped at Morganza, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania in Beaufort, South Carolina (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864. The regiment then headed back to New Orleans, where it arrived later that month.

List of Personal Effects for Private William Herman, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Army of the United States, U.S. General Hospital, Natchez, Mississippi, 1864 (U.S. Army Records, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain; click to enlarge).

As they did during their tour through the Carolinas and Florida, the men of the 47th had battled the elements and disease, as well as the Confederate Army, in order to survive and continue to defend their nation. Among those who fell ill and died during the Red River Campaign was Private William Herman.

Repeatedly treated by regimental physicians for diarrhea, which turned from an episodic to chronic condition, Private Herman was subsequently transported to the U.S. General Hospital in Natchez, Mississippi, where he died from disease-related complications on 23 July 1864. Just thirty years old at the time of his passing, his remains were most likely interred near the hospital and then later exhumed and reinterred at the Natchez National Cemetery; however, the record keeping of Union Army clerks there during this period of the war was haphazard, causing multiple soldiers to be entered on that cemetery’s burial ledgers as “Unknown.” Sadly, Private Herman’s exact burial location has still not been identified more than a century and a half after his death.

U.S. Army records did show that, at the time of his death, the only possessions that he had were: one cap, one flannel sack coat, one flannel shirt, one pair of flannel drawers (underwear), one pair of trousers, one pair of shoes, and one blanket that was made of rubber. A notation by the hospital’s quartermaster indicated that Private Herman’s personal effects were “to be disposed of for the benefit of contrabands” (formerly enslaved men and women).

What Happened to William Herman’s Wife and Children?

Excerpt from attorney Joshua Seiberling’s 1869 affidavit describing his legal work on behalf of Caroline Herman and her children (U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension Files, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain; click to enlarge).

The mind and world of Caroline (Miller) Herman appear to have shattered after she received word that she had been widowed by her soldier-husband. Struggling financially, her behavior became increasing erratic after beginning the process of applying for U.S. Civil War Widow’s and Orphans’ Pension funds in order to keep a roof over her head and the heads of her children.

The wheels of that process, which she had begun sometime after receiving notification of her husband’s death in July 1864, moved at a glacial pace. A resident of Weisenberg Township, Lehigh County during the fall of 1866, the thirty-two-year-old was in a such a precarious position by the end of that year that the attorney helping her with her pension application, Joshua Seiberling, felt compelled to pen an appeal to the U.S. Pension Bureau in which he pleaded with them to speed up their review of her pension claim due to the severe hardships that she and her children were suffering.