Jacob Daub, circa 1862-1865 (carte de visite, Cooley & Beckett Photographers, Savannah, Georgia and Beaufort and Hilton Head, South Carolina, public domain).

Just wide-eyed little boys when their parents escorted them up the ramp of a ship as they fled the aftermath of an unsuccessful mid-1800s revolution in what is now Baden-Württemberg, Germany, Jacob and William Daub could scarcely imagine that, less than a decade later, they would both engage in a life or death struggle to save their adopted homeland from a similar fate.

All they knew at that moment was that they were embarking on a grand adventure with their parents and younger brother Charles.

Formative Years

Born on 14 January 1845 in the Grand Duchy of Baden, Jacob S. Daub was a son of Michael Daub (1810-1865) and Barbara (Trauchler) Daub (1814-1881), and the older brother of William J. Daub (1848-1928) and Charles Frederick Daub (1851-1935). His birth and those of those two younger siblings occurred during one of the most turbulent periods in their nation’s history—the German Revolution of 1848, which was “the last and … greatest of the middle-class revolutions which had convulsed Europe periodically since 1789,” according to Theodore S. Hamerow, late professor emeritus of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and leading expert on the history of German Unification:

“It must have been exciting to be alive in the spring of 1848, that ‘springtime of nations,” when God smiled with favor upon every parliamentary subcommittee and the liberal millennium was just around the corner. Barricades were mushrooming in the capitals of Europe from the Seine to the Danube; angry mobs were stoning royal palaces; unpopular ministers were hastily signing resignations and hurrying into exile; exiled revolutionaries were hurrying home to a hero’s welcome. To liberals witnessing these events it appeared as if a new world were about to be born, as if a new reign of liberty and justice were beginning.”

To the Daub brothers’ parents, those months of optimism must have felt like the perfect time to bring new life into the world, but their joy was soon tempered. Per Hamerow, “the brave dream of a European polity of free individuals organized in free nations turned into a nightmare.”

“The Revolution, greeted as the opening act of a process of cosmic liberation, degenerated before long into a war of all against all, of proletarian against bourgeois, Dane against Prussian, Pole against German, German against Czech. Like the sorcerer’s apprentice, liberalism could not control the forces it had unleashed and was defeated by the Revolution it had created. By 1849 its strength was exhausted, and conservatives returned to the seats of power which liberals had occupied a year earlier. The effect of 1848 was to discredit political ideals and ideologies and to prepare the way for ‘strong’ men, men who at least got what they wanted, even if what they wanted was not always morally justifiable.”

For middle income families, life in Baden became less and less bearable with each passing year. According to historians at the U.S. Library of Congress, in the aftermath of the revolution, “typical working people in Germany … were forced to endure land seizures, unemployment, [and] increased competition from British goods.” Because of these hardships:

“It soon became easier to leave Germany, as restrictions on emigration were eased. As steamships replaced sailing ships, the transatlantic journey became more accessible and more tolerable. As a result, more than 5 million people left Germany for the U.S. during the 19th century….

An army of skilled German workers rolled into American cities … bringing with them the trades they had plied in their homeland. German Americans were employed in many urban craft trades, especially baking, carpentry, and the needle trades. Many German Americans worked in factories founded by the new generation of German American industrialists, such as John Bausch and Henry Lomb, who created the first American optical company; Steinway, Knabe and Schnabel (pianos); Rockefeller (petroleum); Studebaker and Chrysler (cars); H.J. Heinz (food); and Frederick Weyerhaeuser (lumber).The social turmoil of Europe in the 19th century also sent many intellectuals and scholars to the United States. In particular, supporters of the German Revolution of 1848—sometimes called ‘Forty-Eighters’—brought their tradition of vigorous public debate and social activism to bear on the issues facing the U.S., including land reform, abolition, workers’ rights, and women’s suffrage. The student radical Carl Schurz, for example, escaped from Germany after the Revolution and settled in Wisconsin. In the course of a long public life, Schurz served his new country as a farmer, a lawyer, a journalist, a campaigner for Abraham Lincoln’s Republican Party, a Union general, a cabinet official, a U.S. senator, an early member of the conservation movement, and the founder and editor of several newspapers, in both English and German.“

According to economic historian Susan B. Carter, between 1846 and 1854—the time when Michael Daub uprooted his family—the number of German immigrants arriving in the United States increased from 57,500 to 215,000. Viewed simply as a number, those figures alone would be stunning enough, but when placing them in context with the sacrifices made by these individuals and families, it becomes clear that they viewed the promise of safer, freer, and more prosperous lives in America as priceless.

The average cost of a steerage class ticket for just one adult emigrating from Germany in 1853, for example, ranged from 33.50 Prussian thalers (or roughly $23 in U.S. dollars in 1853)—if that adult was sailing from the Port of Hamburg to the Port of New York—to a high of 44 Prussian thalers if that adult was sailing from the Port of Bremen. And the adult steamship steerage fare from Hamburg to New York was even higher, averaging roughly 60.8 thalers. Even more daunting, the fare for just one child (under the age of eight or ten, depending on ship rules), traveling from Hamburg to New York, ranged roughly between 29.3 (by sail) and 46.3 (by steamer). Consequently, “Mid-nineteenth-century German immigrants who settled in the United States and other faraway destinations faced the formidable hurdle of crossing an ocean and coming up with the resources to pay for it,” according to economic historians Raymond L. Cohn and Simone A. Wegge.

“These fares explain why most of the Germans who emigrated were positively self-selected, that is, they were not poor farm laborers or servants but were somewhat better off…. A farm laborer in an average rural village in the Hesse-Cassel principality, for example, made on average 24 Thalers a year. Few of them could afford to emigrate to the United States. Around 1850, even a master farm laborer in the Rhine area earned only about 60 Thalers per year in cash in addition to various in-kind goods, worth probably another 20 Thaler.”

Carpenters and masons generally made more than that, per Cohn and Wegge, but the cost of traveling from Germany to New York, Baltimore, or Philadelphia would likely have been too high even for them because “one transatlantic fare would have cost between one-third and one-half of their yearly income.” As a result, “paying for the voyage was made more feasible in that they would typically liquidate all their goods and property before leaving and/or make use of an inheritance.” And traveling in steerage became the go-to option because “first class … fares averaged two to three times those of steerage” with second-class accommodations still out of reach for most at “about 40 percent higher than steerage.”

Furthermore, “The total cost of the journey for an emigrant would have included the costs incurred in getting to the embarkation point,” according to Cohn and Wegge, as well as overnight lodging while “waiting for the ship to leave” and “the extra expense of getting to their destination after arrival.”

Even so, Michael and Barbara Daub decided that the financial and personal costs were worth it and, when the time came, they brought their boys to the docks sometime around 1852 and boarded the ship that would transport them all to a new world.

A New Life in Pennsylvania

Delaware and Lehigh Rivers at Easton, Pennsylvania, 1844 (Augustus Kollner, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

After emigrating with their parents sometime around 1852, Jacob, William, and Charles Daub settled in Northampton County, Pennsylvania, where their father found work as a stone mason. In 1852, the brothers welcomed another sibling—Theodore G. Daub (1852-1891), who was born in Pennsylvania that same year—making their youngest brother a first-generation American.

By 1860, the Daubs were living in Easton’s West Ward. Federal census records for the year documented that the family’s patriarch owned real estate valued at $300 and other personal property valued at $50 (for a total value in today’s dollars of roughly $11,350). Having gradually reached a place of stability, the Daubs had come to view Easton as “home” because they, like other German immigrants “were still connected by the great web of German-language culture,” according to Library of Congress historians:

“German newspapers were available in most American cities, from California to Texas to Massachusetts, and German-language traveling speakers, theatrical performers, and popular songs all helped keep German Americans in touch with their cultural heritage.”

But as the year waned, their sense of security would be shaken—first by the December 1860 secession of South Carolina from the United States—and then by the drum beat of war tapped out as other southern states choose to follow South Carolina’s belligerent lead.

Civil War

German immigrant Jacob Daub was just sixteen years old when civil war broke out in the United States of America. Choosing to become one of the early responders to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to help preserve the Union, he enrolled for military service in Easton, Pennsylvania on 15 September 1861, and then reported for duty the next day at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, where he officially mustered in as a Musician with Company A of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Muster rolls of the 47th Pennsylvania confirm that he served as a field musician, not as a member of the regimental band, and that he was a drummer boy.

This means that Jacob Daub’s job was to tap out cadences on his drum to position members of his company during the heat of battle and, on calmer days when they weren’t in combat, to strike the less urgent beats that summoned his comrades for meals and daily duty assignments. It also meant that he regularly interacted with Captain Richard A. Graeffe, the commanding officer of the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company. A German immigrant like Daub, Graeffe had previously performed his Three Month’s Service during the opening weeks of the American Civil War with Company G of the 9th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Military records at the time described Jacob Daub as an Easton resident and cigar maker who was 5’4” tall with light hair, blue eyes, and a fair complexion.

Following a brief light infantry training period at Camp Curtain, Drummer Boy Daub and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians headed for Washington, D.C. where they were stationed at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, beginning 21 September 1861. Henry D. Wharton, a Musician with the regiment’s C Company, wrote to the Sunbury American newspaper the next day with the following update:

“After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on discovering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.”

On 24 September 1861, Drummer Boy Daub and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers became members of the U.S. Army when they were officially mustered into federal service. Three days later, they were assigned to Brigadier-General Isaac Stevens’ 3rd Brigade, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, they were on the move again. Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen marched behind their regimental band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (165 steps per minute using 33-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and trudged on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated close to General W. F. Smith’s headquarters, and were now part of the massive Army of the Potomac (also known as “Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

“On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….”

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” for the large chestnut tree located within their camp’s boundaries. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly 10 miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. Also, around this time, companies D, A, C, F, and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left-wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops. In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

“The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….”

On Friday, 22 October, the 47th engaged in a Divisional Review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” Less than a month later, in his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed more details about life at Camp Griffin:

“This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….”

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review overseen by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.” As a reward—and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brannan obtained new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

But these frequent marches and their guard duties in rainy weather gradually began to wear the men down; a number of 47th Pennsylvanians fell ill with fever. Several contracted Variola (smallpox), which was also sickening Confederate troops stationed nearby, and were sent back to Union Army hospitals in Washington, D.C. At least two members of the regiment died from the pox while receiving treatment.

1862

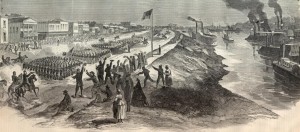

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were transported to Florida aboard the steamship U.S. Oriental in January 1862 (public domain).

Next ordered to move from Virginia back to Maryland, Jacob Daub and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were then transported by rail to Alexandria, where they boarded the steamship City of Richmond. Sailing the Potomac to the Washington Arsenal, they were dropped off and reequipped there before marching away for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C. The next afternoon, they hopped cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

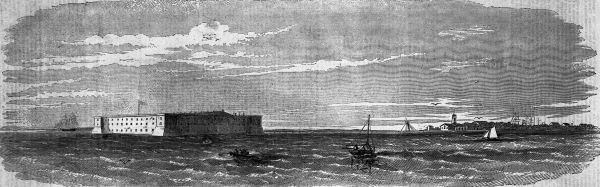

Departing on 27 January 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ferried to the Oriental by smaller steamers with the officers boarding last and, per the directive of their brigade’s commanding officer—Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, they steamed away at 4 p.m. for America’s Deep South. They were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas—and due to the state’s role as “the supplier of the Confederacy.”

Upon their arrival in Key West in early February, they were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor. Drilling daily in heavy artillery tactics, they also strengthened the federal installation’s fortifications. During the weekend of Friday, 14 February, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers introduced their presence to Key West residents by parading behind their regimental band from the fort through the city. That Sunday, members of the regiment mingled with locals at various church services in Key West.

As the days passed, however, an old foe—disease—resurfaced. As a result, a fair number of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer infantrymen would be claimed not by rifle or cannon fire during this phase of service, but by dysentery and typhoid spread by daily life in close military quarters.

Ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina in mid-June, Drummer Boy Jacob Daub and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians pitched their Sibley tents there before receiving improved housing in the Department of the South’s Beaufort District. Picket duties north of the 3rd Brigade’s main staging area were commonly rotated among the various regiments on site during this time, putting soldiers at increased risk from enemy sniper fire. Still, according to historian Samuel P. Bates, the men of the 47th “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing.”

Capture of Saint John’s Bluff and the Battle of Pocotaligo

Ordered to assemble supplies for a return trip to Florida in late September, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania then joined other Union regiments in capturing Confederate troops stationed at key points along the Saint John’s River as part of the Expedition to Saint John’s Bluff from 1 to 3 October 1862. Commanded by Brigadier-General Brannan, the 1,500-plus Union force disembarked from Union gunboat-protected troop carriers at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek. Taking point, the 47th Pennsylvania led the brigade through 25 miles of densely forested swamps populated with alligators and poisonous snakes. By the time it was all over, Brannan’s brigade had forced the Confederates to abandon their artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, and paved the way for the Union to occupy the town of Jacksonville, Florida.

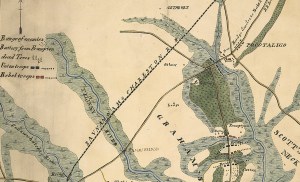

Excerpt from the U.S. Army map of the Pocotaligo-Coosawhatchie Expedition, 22 October 1862, showing the Caston and Frampton plantations in relation to the town of Pocotaligo, the Pocotaligo bridge and the Charleston & Savannah Railroad (public domain).

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th engaged Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point, the men of the 47th were placed on point once again, but they and their fellow 3rd Brigaders were less fortunate this time.

Picked off by snipers while on the move toward the Pocotaligo Bridge, they also faced massive resistance from a heavily entrenched Confederate battery that opened fire on the Union troops as they entered a clearing. Those headed for the higher ground of the Frampton Plantation fared no better, encountering artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests.

Bravely, the Union regiments grappled with the Confederates where they found them, pursuing enemy troops for four miles as they retreated to the bridge where the 47th then relieved the 7th Connecticut. But the Confederates were just too well fortified. After two hours of intense fighting in an unsuccessful attempt to take the ravine and bridge, sorely depleted ammunition supplies forced the 47th’s withdrawal to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th were significant. Two officers and 18 enlisted men died; two officers and an additional 114 enlisted were wounded. Badly battered, the 47th Pennsylvanians returned to Hilton Head on 23 October, where members of the regiment served as the funeral Honor Guard for the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South, Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, who had died from yellow fever on 30 October. Members of the 47th Pennsylvania were given the high honor of firing the salute over his grave.

1863

Jacob Daub’s entry on a 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry muster roll, 1863 (Company A, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain; click to enlarge).

Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, much of 1863 for Drummer Boy Jacob Daub and his A Company comrades was spent garrisoning federal installations in Florida as part of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps, Department of the South. The men from Company A joined with those from Companies B, C, E, G, and I in duties at Key West’s Fort Taylor while the men from Companies D, F, H, and K garrisoned Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the coast of Florida.

It was a noteworthy year not only for the casualties incurred on duty or wrought by disease—but for the clear commitment of the men from the 47th to preserving the Union. Many chose to reenlist when their terms of service expired, opting to finish the fight rather than returning home to families and friends. Among those who chose to stay was Jacob Daub, who re-upped for a second tour of duty as a drummer for Company A on 12 October 1863. A callow teen at the start of his service, he was now a man at nearly twenty years old.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to expand the Union’s reach even further. In response, Captain Graeffe and a group of men from A Company were assigned to special duty involving raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence. Graeffe took his detachment up north to Fort Myers, which had been abandoned in 1858 following the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. Per orders issued earlier in 1864 by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas that the fort be reclaimed to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade, Graeffe and his men revitalized the facility, turning it into both their base of operations and a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate Army deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops. According to Schmidt:

“Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard. Lt. Harris was directed to tow the Matchless if necessary.

Punta Rassa was probably the location where the troops disembarked, and was located on the tip of the southwest delta of the Caloosahatchee River … near what is now the mainland or eastern end of the Sanibel Causeway… Fort Myers was established further up the Caloosahatchee at a location less vulnerable to storms and hurricanes. In 1864, the Army built a long wharf and a barracks 100 feet long and 50 feet wide at Punta Rassa, and used it as an embarkation point for shipping north as many as 4400 Florida cattle….

Capt. Graeffe and company were disembarked on the evening of January 7, and Gen. Woodbury ordered the company to occupy Fort Myers on the south side of the Caloosahatchee , about 12 miles from its mouth and 150 miles from Key West Shortly after, [a detachment of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company stationed on Useppa Island] was also ordered to proceed to Fort Myers and join the main body of Company A, the entire command under direct orders of the General who was in the area…. Gen. Woodbury returned to Key West on the Honduras prior to January 19, and the command was left in charge of Capt. Graeffe who dispatched various patrols in search of refugees for enlistment and for activities involving Confederate cattle shipments.

Company A’s muster roll provides the following account of the expedition under command of Capt. Graeffe: ‘The company left Key West Fla Jany 4. 64 enroute to Fort Meyers Coloosahatche River [sic] Fla. were joined by a detachment of the U.S. 2nd Fla Rangers at Punta Rossa Fla took possession of Fort Myers Jan 10. Captured a Rebel Indian Agent and two other men.’”

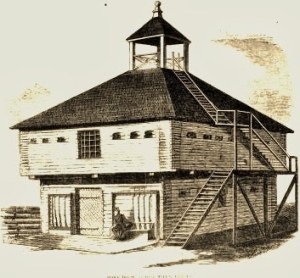

Schmidt notes that Graeffe’s hand drawings show there were roughly 12 buildings “primarily situated along the river, with a log palisade protecting those portions not bounded by the Caloosahatchee; the whole in a densely wooded area and entered through an opening on the southeast protected by the river on the west near the area of the wharf, and a log blockhouse on the east.” During this phase of duty, which lasted until sometime in February of 1864, Graeffe’s A Company men subsequently added more structures and fortifications. They also captured three Confederate sympathizers at the fort, including a blockade runner and spy named Griffin and an Indian interpreter and agent named Lewis. Charged with multiple offenses against the United States, they were transported to Key West, where they were kept under guard by the Provost Marshal—Major William Gausler, third-in-command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Early on, according to Schmidt, Captain Graeffe sent the following report to Woodbury:

“‘At my arrival hier [sic] I divided my forces in three detachment, viz one at the Hospital one into the old guardhouse and one into the Comissary [sic] building, the Florida Rangers I quartered into one of the old Company quarters, I set all parties to work after placing the proper pickets and guards at the Hospital i have build [sic] and now nearly finished a two story loghouse of hewn and square logs 12 inches through seventeen by twenty-two fifteen feet high with a cupola onto the roof of six feet high and at right angle with two lines of picket fences seven feet high. i shall throw up a half a bastion around it as soon as completed. around the old guardhouse i have thrown up a bastion seven feet through at the foot and three feet on the top nine feet high from the bottom of the ditch and five on the inside. I also build [sic] a loghouse sixteen by eighteen of two storys [sic] Southeast of the Commissary building with a bastion around it at right angles with a picket fence each bastion has the distance you recomandet [sic] from the loghouses 20 feet on the sides and 20 to the salient angle, i caused to be dug a well close to bl. houses and inside of the bastions at each Station inside they are all comfortable fitted up with stationary bunks for the men without interfering with the defence [sic] of the work outside of the Bastions and inside the picket fense i have erected small kitchens and messrooms for each station, i am building now a guardhouse build [sic] of square hewn logs sixteen by sixteen two storys high the lower room to be used for the guard and the upper one as a prison, the building to be used for defence [sic] (in case of attack) by the Rangers each work is within view and supporting distance from the other; Capt. Crane with a detachment of his men repaired the wharf, which is in good condition now and fit for use, the bakehouse i got repaired, and the fourth day hier [sic] we had already very good fresh bread; the parade ground is in a good condition had all the weeds mowed off being to [sic] green to burn. i intend to fit up a schoolroom and church as soon as possible.’”

Muster rolls for Company A from this period noted that “a detachment of 25 men crossed over to the north west side of the river” on 16 January and “scoured the country till up to Fort Thompson a distance of 50 miles,” where they “encountered a Rebel Picket who retreated after exchanging shots.” Making their way back, they swam across the river, and reached the fort on 23 January. Meanwhile, while that group was still away, Captain Graeffe ordered a smaller detachment of eight men to head out on 17 January in search of cattle. Finding only a few, they instead took possession of four barrels of Confederate turpentine, which were later disposed of by other Union troops.

A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documents the time of Richard Graeffe and the men under his Florida command this way:

“A small contingent of 20 men and two officers from the Pennsylvania 47th Regiment, led by Captain Henry Crain of the 2nd Regiment of Florida, arrived at the fort on January 7, 1864. A short time later, the party was joined by another small detachment of the 47th under the command of Captain Richard A. Graeffe. Over a short period, increasing reinforcements of the fort led to increasing cattle raids throughout the region. A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.”

* Note: The detachment which served under Graeffe at Fort Myers has been labeled as the Florida Rangers in several publications, including The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, prepared by Lieutenant Colonel Robert N. Scott, et. al. (1891).

Over the next several weeks, Graeffe continued to send out detachments from his company—all in search of Confederate cattle and other supplies. On 22 January, one such group “scoured the banks of Black Creek a distance of thirty miles capturing 8 bales of cotton and four barrels of turpentine and two horses” while A Company muster rolls noted the following at the start of the new month:

“Feby 2nd a detachment of 45 men ordered on a scout. The first day 2 Ocl P.M. while in bivouac were attacked by the enemy, who retreated after exchanging a few volleys, one man slightly wounded on our side. On the 4th inst. Encountered a superior force of the enemy cavalry who retired on our approach. We dare them to incite them to action but without avail. returned to Fort Myers Feby 6. Fortified the station by erecting three block houses surrounding them with earth bastions and inclosing an area of 6 acres with a strong picket fence. Feby 24 received orders to return to Key West to join the regt. Feby 28, arrived at Key West, Fla.”

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had already left on the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana.

Red River Campaign

Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reunited regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, Drummer Jacob Daub and his fellow A Company men were effectively placed on a new type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.

But they had missed the two bloodiest combat engagements that the 47th Pennsylvania would endure during the Red River Campaign—the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield on 8 April and the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April. According to Schmidt, Company A was soon ordered to return the Confederate prisoners to New Orleans, and officially ended their detached duty on 27 April when they rejoined the main regiment’s encampment at Alexandria.

This means that the men from Company A also missed a third combat engagement—the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry”), which took place on 23 April.

From late April through mid-May, the fully reassembled 47th Pennsylvania engaged in the hard labor of fortification work, and also helped to build “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that enabled Union gunboats to navigate the treacherous waters of the Red River. Beginning 13 May, the regiment headed for Morganza, and then reached New Orleans on 20 June. Along the way, disease claimed still more men.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Undaunted by their travails in Bayou country, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers continued their fight to preserve the Union during the summer of 1864. After receiving orders on the 4th of July to return to the East Coast, they did so in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I steamed for the Washington, D.C. area beginning 7 July while the men from Companies B, G and K remained behind on detached duty and to await transportation. (Led by F Company Captain Henry S. Harte, they finally sailed away at the end of the month aboard the Blackstone, arrived in Virginia on 28 July, and reconnected with the bulk of the regiment at Monocacy, Virginia on 2 August.)

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, Drummer Jacob Daub and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians joined up with Major-General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July 1864. Following their participation in the Battle of Cool Spring, they then helped defend Washington, DC yet again while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah from August through November of 1864, it was here at this time and this place that the now full-strength 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would engage in their greatest moments of valor. Records of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers confirm that the regiment was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, Virginia in early August 1864. Executing a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville and other locations within the vicinity (Middletown, Charlestown and Winchester), Sheridan’s Union forces fought a “mimic war” with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early. From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers engaged in the Battle of Berryville, as well as post-battle skirmishes with the enemy.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, c. 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Inflicting heavy casualties during the Battle of Opequan (also known as “Third Winchester”) on 19 September, Sheridan’s gallant men forced a stunning retreat of Jubal Early’s Confederates—first to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September) and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack. Their victories helped Abraham Lincoln win a second term as President.

Their lives then changed dramatically on 23-24 September 1864 when their two most senior regimental commanders—Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant Colonel George W. Alexander—mustered out upon the expiration of their respective terms of service, and were replaced by John Peter Shindel Gobin, who quickly became equally respected.

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, Surprise at Cedar Creek, which captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

The 47th Pennsylvanians and other members of Sheridan’s Army then began the first Union “scorched earth” campaign, starving Confederate forces and their supporters into submission by destroying Virginia’s farming infrastructure. Viewed by many today as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents, but contributed to the turning of the war further in favor of the Union. Early’s men, weakened by hunger, strayed from battlefields in increasing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling Sheridan’s men to rally and win the day during the Battle of Cedar Creek.

From a military standpoint, it was an impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October 1864, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Capturing Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles, they were also successful in pushing seven Union divisions back until, according to Bates, “the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat.”

“Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he rode rapidly past them – ‘Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

After the Union’s counterattack pounded Early’s forces into submission, the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, decades later, would be awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions further as follows:

“When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went ‘whirling up the valley’ in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.”

Through it all, the casualty rates for the 47th mounted with the regiment ultimately losing nearly the equivalent of two full companies of men. Given a slight respite after Cedar Creek, the 47th Pennsylvanians were quartered at Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December before receiving orders to assume outpost duty at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia just five days before Christmas.

1865

Spectators mass at the Capitol Building for the Grand Review of the Armies, May 1865. Note flag at half-mast, following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

By February of 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were serving as part of the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah. That month, the regiment gained another new member when Jacob Daub’s younger brother, William J. Daub, enrolled for military service back home. After officially mustering in that same day as a private with his brother’s unit—Company A of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry—he officially joined the regiment on 12 March 1865 at Camp Fairview. A nineteen-year-old carpenter who had been living in Delaware Township, William Daub was described on military records as being 5’7” tall with brown hair, gray eyes, and a ruddy complexion.

On 19 April, the Daub brothers and their regiment became actively engaged in protecting Washington, DC—ordered to defend the nation’s capital following the recent assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. While serving with the 47th in the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps (Dwight’s Division), they also participated in the Union’s Grand Review of the Armies on 23-24 May. Letters home during this period and interviews conducted in later years with survivors of the 47th Pennsylvania confirm that at least one member of the 47th was given the honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while still others were assigned to guard duties at the prison where the alleged Lincoln assassination conspirators were held and tried.

Taking one final swing through the South, the 47th was subsequently stationed in Savannah, Georgia from 31 May to 4 June, as part of the Department of the South’s 3rd Brigade (Dwight’s Division), and in Charleston, South Carolina beginning in June.

Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

Duties during this time were Provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related, including rebuilding railroads and other key aspects of the region’s infrastructure that had been damaged or destroyed during the long war.

Still on duty six months after the war’s end, the Daub brothers received the sad news that their father, Michael Daub, had died. Unable to travel home for the funeral, they would not be able to visit his grave at the Easton Cemetery in Northampton County, Pennsylvania until after their terms of enlistment were completed.

Finally, on Christmas Day in 1865, they and the majority of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers began mustering out forever—a process which continued through early January 1866. Enduring a stormy voyage home, they traveled by train to Philadelphia, where they received their honorable discharge papers at Camp Cadwalader during the second week of the New Year. Before that week was over, they were back in Northampton County, enjoying the company of their loved ones and neighbors.

Return to Civilian Life

Finally home for good, Jacob and William J. Daub tried to regain some semblance of a normal life. On 11 November 1865, the older brother of the two—Jacob—welcomed the birth of his first child, Minnie Daub (1865-1953), with Adeline Weiss (1848-1926), a daughter of John Weiss (1806-1855) and Anna (Back) Matt Weiss. Jacob and Adeline later married on 21 September 1867 at Easton’s First United Methodist Church.

Then, on 18 May 1868, the couple welcomed their second child—son John Daub (1868-1951), who would ultimately grow up to become a mechanical engineer.

Meanwhile, William J. Daub found work as a laborer and made plans to become a Naturalized Citizen of the United States—a goal he achieved in 1869, according to the 1920 U.S. Census. By 1870, he had also begun a family of his own. He and his new wife Elizabeth (Eichman) Daub (1850-1915)—also known as “Elsie”—chose to establish their family home in South Easton.

More children soon followed.

For Jacob and Adeline Daub, this meant celebrating the births of: George W. Daub (1871-1936), who was born on 13 May 1871 and went on to become a fireman; Mary A. Daub (1872-1928), who was born on 28 November 1872 and went on to marry Wilson Fretz; Sallie Daub (August 1876-December 1919), who went on to wed Robert Lusby; and Oscar Daub (1876-1960), who was born in February 1876. By 1880, their family was also residing in South Easton, where Jacob was employed as a store clerk. Less than a year later, in April 1881, his widowed mother, Barbara (Trauchler) Daub, passed away. Living by herself according to the 1880 federal census, she was in her mid-sixties at the time of her death, and was interred at the Easton Cemetery.

Meanwhile, during these same two decades, William J. Daub’s family and good fortune had also grown. His son, Theodore Eichman Daub (1874-1935), opened his eyes in Northampton County for the first time on 20 February 1874, and was baptized at the Methodist Church in Easton on 17 July of that year while daughter Grace Elizabeth Daub (1875-1972) made her first appearance on 30 June 1875. She was then baptized at the same church on 12 February 1876. Employed as a furniture dealer by 1880, William Daub operated his business from 403 and 405 Northampton Street, and lived with his family in the “Southern District” of Easton’s Sixth Ward. His youngest brother, Theodore G. Daub, worked nearby—operating a grocery at the corner of Third and Lehigh streets. In 1888, William Daub became even more active in the business affairs of his adopted hometown as one of the leaders of the newly formed Easton Industrial Association, which helped new businesses obtain financial startup and expansion support.

Life went smoothly for roughly a decade for both Daub families, but in the late spring/early summer of 1891, their youngest brother, Theodore G. Daub, suffered an untimely death. Following his passing while still in his thirties, he was buried at the Easton Cemetery. An accident then nearly ended the life of Jacob Daub in the fall of 1895. According to the 29 October edition of The Allentown Leader:

“Jacob Daub, an Easton grocer, was severely injured yesterday while out driving. The accident occurred near Raubsvllle. The horse made a sudden plunge to one side of the road and the grocer was thrown headforemost to the ground. He managed to walk to the residence of a farmer nearby, where he soon afterwards became unconscious. He suffered concussion of the brain.”

Jacob Daub eventually recovered and, employed as a carpenter after the turn of the century, he lived in a rental home at 203 Third Street in Easton’s First Ward with his wife and children: Minnie, a dressmaker; Sallie (who was not working according to the federal census), and Oscar, a grocery clerk. Daughter Minnie then began her own family in 1905 when she wed widower and Bucks County native Peter Carty on 16 October in Allentown, Lehigh County.

Still residing in the same rental in 1910, the revised household included laborer Jacob Daub and his wife, their daughter Sallie and her husband, Robert Lusby (a laborer who had emigrated from England), and the Lusby’s nineteen-month-old daughter, Marion. The federal census that year also documented that Jacob Daub and his wife had been married for forty-three years, and had greeted the births of six children—all of whom were still living, that his daughter Sallie had been married for two years, and that neither Jacob nor Robert were naturalized citizens.

Sadly, Sallie (Daub) Lusby preceded both of her parents in death when she passed away in her early forties. Ill for a year, she became paralyzed and suffered a stroke on 8 December 1919, and died the following day. She was subsequently laid to rest at the South Easton Cemetery in Easton, Pennsylvania.

During this same period, life had also become more difficult for Jacob’s brother, William. Widowed when his wife passed away in March of 1915, he worked as a manufacturer with a furnace company in 1920, and lived with his son Theodore E. Daub, who was also engaged in the same profession. Also residing at Theodore’s home were Theodore’s sister Grace, wife Mathilda (1879-1967), and children—son William John, II and daughter Elsie Louise.

Less than five years later, on 10 February 1926, Jacob Daub then also became a widower when his wife Adeline passed away in Easton. Like her daughter before her, Adeline Daub was interred at the South Easton Cemetery in Easton, Pennsylvania.

Jacob then lost his both his daughter, Mary, and his true brother-in-arms, William J. Daub, in the same year. Diagnosed with diabetes, Mary A. (Daub) Fretz suffered an attack of apoplexy on 14 August 1928, died the next day, and was buried on 18 August at the South Easton Cemetery. She was roughly three months shy of her 56th birthday. William J. Daub then succumbed to complications from heart disease in Easton at the age of 80 years, 10 months, and 27 days on 16 December 1928. He was laid to rest at the Easton Cemetery three days later.

The health of Jacob Daub’s younger brother, Charles Frederick Daub, a realtor, also began to decline. Battling heart and high blood pressure issues, Charles suffered a cerebral hemorrhage in the fall of 1935, and died on 21 October. He was buried three days later at the Easton Cemetery.

William J. Daub’s son, Theodore E. Daub, then suffered a cerebral thrombosis just over three weeks later—on 14 November 1935—and died at the Easton Hospital on 23 November. He, too, was laid to rest at the Easton Cemetery.

Jacob Daub’s son, George W. Daub, then succumbed from complications from diabetes and arteriosclerosis on June 24, 1936, and was laid to rest at the Hays Cemetery in Easton.

Even with all of this heartache, the former Civil War drummer boy stayed involved in community and social activities. In 1925, 1927, and 1930, Jacob Daub attended the annual reunions of the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, which were held in Allentown in October of each year to mark the anniversary of the regiment’s first true combat experience—the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina.

Death and Interment

But time finally also caught up with the old soldier on 4 December 1936. He succumbed to the combined effects of myocarditis, chronic nephritis, and arteriosclerosis at 5:30 that evening in Raubsville, Williams Township, Northampton County. Aged ninety years, ten months, and eighteen days, he was laid to rest on 7 December at the South Easton Cemetery. His son, John, a resident of Plainfield, New Jersey, served as the informant for the death certificate.

Among the children of Jacob Daub who also went on to live long lives, John William Daub, had married Mary Elizabeth Jones and relocated to Plainfield in 1898. An active member and trustee of the Monroe Avenue Methodist Church for more than half a century, he was employed for many years as a mechanical engineer by Walter Scott and Co., Inc. until retiring in 1946. He was eighty-four when he died at his New Jersey home on 27 September 1951. He, too, was interred at the Hays Cemetery in Easton, Pennsylvania.

Daughter Minnie (Daub) Carty also made it to the mid-20th century. Eventually weakened by diabetes, she sustained a hip fracture at the age of eighty-seven during a severe fall on 18 September 1953, and died the same day at the Betts Hospital Clinic in Easton. She was laid to rest at the Easton Cemetery three days later.

Meanwhile, son Oscar, who had married Amanda Boas in 1902, lived to see the start of the 1960s. After welcoming the Easton births of daughter Florence sometime around 1903 and of son Frank J. Daub (1907-1989) on 10 November 1907, he worked as a salesman and clerk during his children’s formative years. Preceded in death by his wife, who had succumbed to cancer in 1927, he later moved into a boarding house in Milford, New Jersey, and paid the rent in 1930 by working as a laborer at a paper mill. Remarried sometime before 1940 and employed as a core cutter at a paper mill, he resided with his second wife, her two children, and his two grandchildren in Alexandria, New Jersey. Following his death in Washington, New Jersey in December 1960, his remains were returned to Easton, and he was laid to rest near his first wife in the Boas family section of the Easton Heights Cemetery.

But it was daughter Grace Elizabeth Daub who had, perhaps, the most adventurous life of them all. Blessed with the financial means to travel, she spent part of her summer in Europe in 1935, departing from Le Havre, France to return home aboard the S.S. Normandie. Sixty-one years old and still single in 1936, she waited for Santa’s arrival aboard the Queen of Bermuda, which departed from Hamilton, Bermuda on Christmas Eve and arrived at the Port of New York the day after Christmas. A resident of an apartment on Lehn Court in Easton, Pennsylvania for more than three decades, she lived her final days at the Good Shepherd Nursing Home in Allentown, and died there on 15 May 1972. Ninety-seven years old at the time, she was buried at the Easton Cemetery.

Sources:

- “A New Surge of Growth,” and “Urban German,” in “Immigration and Relocation in U.S. History,” in “Classroom Materials.” Washington, DC: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online 4 July 2021.

- “16 Veterans at Reunion,” in “Local News.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 27 October 1927.

- “A Grocer Hurt in a Runaway.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 29 October 1895.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, Vol 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Carter, Susan B. et. al. (eds.) Historical Statistics of the United States (Millennial Edition). New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Charles Frederick Daub, in Death Certificates (file no.: 91087, registered no.: 654). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, 1935.

- Cohn, Raymond L., and Simone A. Wegge. “Overseas Passenger Fares and Emigration from Germany in the Mid-Nineteenth Century,” in Social Science History, Vol. 41, No. 3, Fall 2017, pp. 393-413. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

- Condit A.M., Rev. Uzal. The History of Easton, Penn’a from the Earliest Times to the Present, 1739-1885. Washington, DC: West & Condit, 1885.

- Daub, Grace, in “New York, U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists” (Le Havre, France: 1935 and Bermuda: 1936). Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com.

- Daub, Jacob and William, in Pennsylvania Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1865. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Daub, Jacob and William, in Civil War Muster Rolls, in “Records of the Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs” (Record Group 19, Series 19.11: 47th Regiment: Company A). Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission, 1861-1865.

- Daub, Jacob and William, in “Records of Places of Burials of Veterans, 1936” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Military Affairs, 1928 and 1939.

- Daub, Jacob and William, in “Registers of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-1865 (47th Regiment: Company A), in “Records of the Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs,” Vol. 3. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Daub, Jacob, William J. Daub, and other Daub family members, in U.S. Census (Northampton County, Pennsylvania: 1860, 1870, 1880,1890-Special Veterans’ Schedule, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930). Washington, DC: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Daub, Oscar, in U.S. Census (Northampton County, Pennsylvania and New Jersey: 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940). Washington, DC: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War: ‘Supplier of the Confederacy.” Tampa, Florida: Florida Center for Instructional Technology, University of South Florida (College of Education), retrieved online January 15, 2020.

- “G.A.R. and Civil War Veterans Gather at Reunion” (photo with caption). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 26 October 1930.

- George W. Daub, in Death Certificates (file no.: 60361, registered no.: 399). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, 1936.

- “Grace Daub Dies in Her 97th Year.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 23 May 1972.

- Hamerow, Theodore S. “History and the German Revolution of 1848,” in The American Historical Review, Vol. 60, No. 1, October 1954, pp. 27-44. Oxford University Press, 1954.

- Jacob Daub, in Death Certificates (file no.: 80755, registered no.: 718). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, 1936.”

- “John W. Daub Was an Engineer.” Bridgewater, New Jersey: The Courier-News, 28 September 1951.

- John W. Daub, in “U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007.” Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com, 2015.

- Minnie Carty, in Death Certificates (file no.: 116003, registered no.: 418). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania: Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, 1936.

- Minnie Daub and Peter Carty, in “Marriage License Docket of Lehigh County, PA. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Clerk of the Orphans’ Court, Lehigh County, 1905.

- Oscar Daub, Amanda E. Boas, and Frank J. Daub, in “U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007.” Provo, Utah: Ancestry.com, 2015.

- Oscar Daub and Amanda Boas, in “Marriage Indexes.” Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey State Archives, 1902.

- Sallie Lusby, in Death Certificates (file no.: 120188, registered no.: 604). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, 1919.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Scott, Robert N. The War of War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series I, Vol. XXXIV, Part II: “Correspondence, etc.-Union,” Chapter XLVI: “Louisiana and the Trans-Mississippi,” p. 199. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1891.

- Staubach, Lieutenant Colonel James C. “Miami During the Civil War: 1861-65,” in Tequesta: The Journal of the Historical Association of Southern Florida, Vol. LIII, pp. 31-62. Miami: Historical Museum of Southern Florida, 1993.

- Tamiami Trail Modifications: Next Steps—Draft Environmental Impact Statement, Appendix E. Washington, DC: U.S. National Park Service: Everglades National Park: 29 January 2010.

- Theodore Eichman Daub, Grace Elizabeth Daub, and William J. and Elsie Ann Daub, in Birth and Baptismal Records. Easton, Pennsylvania: Christ United Methodist Church, 1874 and 1876.

- Theodore E. Daub, in Death Certificates (file no.: 99836, registered no.: 704). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, 1936.

- Wharton, Henry D. Letters from the Sunbury Guards. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1861-1868.

- William J. Daub, in Death Certificates (file no.: 116884, registered no.: 739). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, 1929.

You must be logged in to post a comment.