Alternate Spellings of Surname: Draubaugh, Drawbaugh

Born on Christmas Day in 1841 in York County, Pennsylvania, Tempest T. Draubaugh was a son of Jacob Draubaugh (1807-1882) and Elizabeth (Overdier) Draubaugh (1804-1861), and the brother of: Eli (1831-1879), Samuel O. (1836-1899), Rebecca (born in 1838), and half-siblings Mary A. (born on 26 February 1844), John (born sometime around 1845) and William (born sometime around 1846).

He was baptized as a Lutheran at Rossville in York County on 12 October 1845. Apparently a group ceremony, Tempest’s parents and siblings (Samuel, Rebecca and Mary) are all listed on a transcribed record of the event as having been baptized that day. Although the family surname has often been spelled in transcribed records as “Drawbaugh,” it was spelled as “Draubaugh” on Tempest’s gravestone.

Formative Years

In 1850, Tempest Draubaugh resided with his parents and siblings, Samuel, Rebecca, Mary, John and William, in Warrington Township, York County where the Draubaugh patriarch was a farmer.

By 1860, Tempest Draubaugh was a teacher in the common school of Monaghan Township, York County, and was residing at the home of his older brother, Samuel, who had married and begun his own family. Their new hometown was known for its abundance of apple and peach trees.

But their promising early days were marred by the storm clouds of national discord. On 20 December 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union, followed by Mississippi (9 January 1861), Florida (10 January 1861), Alabama (11 January 1861), Georgia (19 January 1861), Louisiana (26 January 1861), and Texas (1 February 1861).

With the fall of Fort Sumter in mid-April 1861, America was at war.

Military Service

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War. (Public domain, U.S. Library of Congress.)

On 24 June 1863, at the age of 21, Tempest T. Draubaugh enrolled for Civil War military service at Harrisburg in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, and then officially mustered in at Harrisburg on 1 July as a Private with Company I, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Military records at the time described him as being 5’9″ tall with brown hair, hazel eyes and a fair complexion.

Private Tempest Draubaugh connected with the 47th Pennsylvania on 27 September 1863 via a recruiting depot on 27. By the time he arrived in Florida where the 47th was stationed, his longer serving I Company comrades had already been bloodied in the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina (21-23 October 1862), and had become somewhat integrated when several young black men who had been freed from the Beaufort area of South Carolina opted to enroll for service with the 47th.

When Private Draubaugh arrived, he became one of the men from I Company and Companies A, B, C, and E to garrison Fort Taylor. (Soldiers from the regiment’s other half – Companies D, F, H, and K – were stationed at Fort Jefferson in Florida’s remote Dry Tortugas.)

During this phase of duty, disease was a constant companion and foe.

1864

After settling into the routine at Fort Taylor and spending his first Christmas (and first birthday) away from home, life changed abruptly for Private Tempest Draubaugh. In February 1864, one of his direct superiors – Captain Coleman A. G. Keck – became too ill to continue in his role as the commanding officer of I Company, and resigned his commission due to failing health.

On 24 February 1864, three days after Captain Keck’s resignation, Private Draubaugh and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians set off for a phase of service in which the regiment would truly make history. Steaming first for New Orleans via the Charles Thomas, the 47th Pennsylvanians arrived at Algiers, Louisiana on 28 February, and were then shipped by train to Brashear City. Following another steamer ride – to Franklin via the Bayou Teche – the 47th joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps. In short order, the 47th would become the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union General Nathaniel Banks.

From 14-26 March, Private Draubaugh and the men of Company I – now under the command of their 1st Lieutenant Levi Stuber – joined with their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians in trekking through New Iberia, Vermillionville, Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches, Louisiana.

On 4 April 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania added to its roster of young black soldiers when 18-year-old John Bullard enrolled for service with Company D at Natchitoches, Louisiana. According to his entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives, he was officially mustered in for duty there on 22 June “as (Colored) Cook.”

Often short on food and water, the men encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Mansfield-Sabine Cross Roads, DeSoto Parish, Louisiana, April 1864. (Source: General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign report; public domain.)

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, 60 members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads. The fighting waned only when darkness fell as those who were uninjured, but exhausted collapsed beside the gravely wounded. After midnight, the surviving Union troops finally were ordered to withdraw to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner and son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

Casualties were once again severe. Lieutenant Colonel George W. Alexander, the regiment’s second in command, was nearly killed, and the regiment’s two color-bearers, both from Company C, were also wounded while preventing the American flag from falling into enemy hands. Corporal William Frack of I Company was killed in action while I Company’s Sergeant William Haltiman (alternate spelling “Halderman”) and Corporal William H. Meyers of were among those who were wounded in battle.

Others from the 47th were captured, marched roughly 125 miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as prisoners of war (POWs) until released during prisoner exchanges beginning 22 July 1864. At least two men from the 47th never made it out of that camp alive, including I Company’s Private Frederick Smith who died at Camp Ford 4 May 1864; another member of the regiment died while being treated at the Confederate Army hospital in Shreveport, Louisiana.

Another member of I Company – Private Owen Fetzer – died on 19 April 1864 at a Union Army hospital in New Orleans.

Following what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, the 47th fell back to Grand Ecore, where the men resupplied and regrouped until 22 April. Retreating further to Alexandria, the 47th Pennsylvanian Volunteers and their fellow Union soldiers then scored a clear victory against the Confederates at Cane Hill.

Named “Bailey’s Dam” for the officer ordering its construction, Lt. Col. Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River in Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 eased Union gunboat passage (public domain).

On 23 April, the 47th and their fellow brigade members crossed the Cane River via Monett’s Ferry and, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Bailey, helped to build a dam from 30 April through 10 May, to enable federal gunboats to easily traverse the Red River’s rapids. On 12 May, Private William Baumeister was transferred to the Veteran Reserve Corps (also known as the “invalid corps”).

Beginning 16 May, I Company moved with most of the 47th from Simmsport across the Atchafalaya to Morganza, and then to New Orleans on 20 June. While there they learned, on the 4th of July 1864, that their fight was not yet over as the regiment received new orders to return to the East Coast for further duty.

During this transition, a number of members of the regiment would be left behind to convalesce, deemed to ill to make the journey; many of these men died in hospitals in New Orleans while the 47th was on the move.

Removed from command amid the controversy over the Union Army’s successes and failures during the Red River Expedition, Union General Nathaniel P. Banks was placed on leave by President Abraham Lincoln. Banks later spent much of his time in Washington, D.C. as a Reconstruction advocate for Louisiana.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Still able and willing to fight after their time in Bayou country, the soldiers of Company I and the men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies A, C, D, E, F, and H steamed aboard the McClellan beginning 7 July 1864.

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, they joined up with General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July 1864. There, they fought in the Battle of Cool Spring and, once again, assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August, the first day of the month arrived with the promotion of 1st Lieutenant Levi Stuber to the rank of Captain and commanding officer of I Company.

The next month – September 1864 – saw the departure of several 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who had served honorably, including I Company’s 2nd Lieutenant James Stuber, Corporals Francis Daeufer, John W. H. Diehl, T. W. Fitzinger, Henry Miller, and D. H. Nonnemacher, and Privates Theodore Baker, W. Fenstermaker, Allen P. Gilbert, William F. Henry, Charles Kaucher, Edwin Kiper, Xaver Kraff, Ogden Lewis, Peter Lynd, Aaron McHose, Gottlieb Schweitzer, William Smith, John L. Transue, John Troxell, Daniel Vansyckel, Henry W. Wieser, and Samuel Wierbach of I Company. All mustered out 18 September 1864 upon expiration of their respective service terms.

Those members of the 47th who remained on duty were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill, September 1864

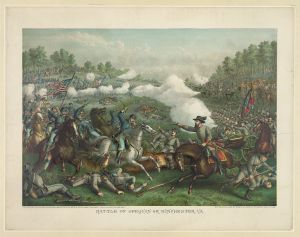

Together with other regiments under the command of Union General Philip H. (“Little Phil”) Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company I and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”). The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces (Kurz & Allison, c. 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. After finally reaching Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with the Confederate Army commanded by Early. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and the 19th Corps were directed by General William Emory to attack and pursue Major General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as another Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops trying to cross a clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice – once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

The 19th Corps, with the 47th in the thick of the fighting, then began pushing the Confederates back. Early’s “grays” retreated in the face of the valor displayed by Sheridan’s “blue jackets.” Leaving 2,500 wounded behind, the Rebels retreated to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September), eight miles south of Winchester, and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union men which outnumbered Early’s three to one.

On the day of the Union’s success at Opequan (19 September 1864), several men from I Company received promotions, including 1st Sergeant Theodore Mink, who advanced to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. Corporals William H. Meyers and Edwin Kemp were promoted to the rank of Sergeant while Privates Thomas N. Burke and Allen Knauss became corporals. Private Oscar Miller was then mustered out the next day, on 20 September, upon expiration of his term of service.

Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek. Moving forward, they and other members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but would do so without two more of their respected commanders. Colonel Tilghman H. Good, the regiment’s founder and original commanding officer, and Good’s second in command, Lieutenant Colonel George W. Alexander, both mustered out 23-24 September upon expiration of their respective terms of service.

Fortunately, they were replaced by others equally admired both for temperament and their front line experience, including John Peter Shindel Gobin, a man who would later go on to become Lieutenant Governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

Battle of Cedar Creek, October 1864

It was during the Fall of 1864 that General Philip Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s crops and farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents – civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles – all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he rode rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

The Union’s counterattack punched Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked.” Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

Once again, the casualties for the 47th were high. Sergeant William Pyers, the C Company man who had so gallantly rescued the flag at Pleasant Hill was cut down and later buried on the battlefield. Regimental Chaplain William Rodrock suffered a near miss as a bullet pierced his cap.

Within the contingent from I Company, Privates John/Jonathan Bartholomew, Francis K. Guildner (alternate spelling “Gildner”), James Lutz and Joseph Stephens were killed in action. Corporal Allen Knauss sustained a gunshot wound to the right side of his face while Sergeant William H. Myers and Privates John Gross, William Martin and Thomas Zigler were also wounded in action.

As with the Red River Campaign, men from the 47th Pennsylvania were also captured by Rebel soldiers and carted off to Confederate prisons at Andersonville (Georgia), Richmond (Virginia) and Salisbury (North Carolina). Of those held as POWs at this time, only a handful survived; the precise location of the graves dug for many of those who didn’t remains unknown.

On 23 October 1864, Company I became another of the 47th Pennsylvania’s integrated companies with Order No. 70, which directed that John Bullard be transferred from the 47th’s Company D to I Company. Bullard, who had mustered in as a Cook while the regiment was stationed in Louisiana, would continue to serve with I Company for the duration of the war.

Following these major engagements, the 47th was ordered to Camp Russell near Winchester, Virginia from November through most of December. Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th was then ordered to outpost and railroad guard duties at Camp Fairview, Charlestown, West Virginia five days before Christmas.

1865 – 1866

Attached to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah in February 1865, the men of the 47th moved back to the Washington, D.C. area via Winchester and Kernstown. Beginning 19 April, the 47th Pennsylvanians were responsible for helping to defend the nation’s capital – and did so in the wake of the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Encamped near Fort Stevens, the 47th Pennsylvanians were given new uniforms and other supplies.

Matthew Brady photographed spectators massing for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865; note crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half mast after President Lincoln’s assassination (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Letters home during this time and newspaper interviews conducted later with with survivors of the 47th indicate that at least one member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while others from the 47th may have been assigned to guard the Lincoln assassination conspirators during the opening days of their imprisonment and trial.

On 22 May 1865, Captain Levi Stuber was promoted from his role as I Company’s commanding officer to service on the regiment’s central command staff at the rank of Major; 1st Lieutenant Theodore Mink was then advanced to the rank of Captain, I Company. The next two days were filled with great pomp and ceremony when, as part of Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, Private Draubaugh and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians marched in the Union’s Grand Review of the Armies.

Final Tour of Duty

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives, public domain).

An early thinning of the ranks began on 1 June 1865 when a General Order from the U.S. Office of the Adjutant General provided for the honorable discharge of several members of the 47th, including men from I Company.

Ordered back to the Deep South, Private Tempest Draubaugh and the remaining members of the 47th Pennsylvania served in Savannah, Georgia from 31 May to 4 June. Attached again to Dwight’s Division, they were now part of the 3rd Brigade, Department of the South.

Relieving the 165th New York Volunteers in July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers quartered in the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury at Charleston, South Carolina. Duties during this phase of service were largely Provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related (including the repair of railroads and other key elements of the region’s infrastructure which had been damaged or destroyed during the long war).

As with their prior southern tour of duty, disease stalked the 47th. Men who had survived the worst in battle were now felled by fevers, tropical diseases, dysentery, or the harsh climate. Many died, and were initially interred at Charleston’s historic Magnolia Cemetery before being exhumed and reinterred later at the Beaufort or Florence national cemeteries; others still rest in unidentified graves. One of those men, I Company’s 2nd Lieutenant William H. Halderman (alternate spelling “Haltiman”), survived being wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana only to suffer severe sunstroke while on duty in South Carolina. He died on 23 July 1865 at Pineville.

Finally, beginning on Christmas Day (Tempest Draubaugh’s birthday), the majority of the men from Company I began to honorably muster out at Charleston, South Carolina – a process which continued through early January. Following a stormy voyage home, the weary 47th Pennsylvanians disembarked in New York City, and were then shipped to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader on 9 January 1866, they were officially given their discharge papers.

Return to Civilian Life

John, an ailing Virginia blacksmith, Hospital Sketches, Louisa May Alcott, c. 1870s (public domain).

Although a significant percentage of the soldiers who served with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers married and started families after returning home to their beloved Keystone State, Tempest T. Draubaugh never did. He was, quite simply, just too ill.

On 20 April 1866, he filed for his U.S. Civil War Veterans’ Pension and, by 1870, he was shown on the federal census as residing with his father. Although his father was still described as a farmer on this census, Tempest Draubaugh was listed only as “at Home” – signaling that he was too ill to work.

Death records confirm this fact. At some point either during his Civil war service or shortly thereafter, Tempest T. Draubaugh contracted tuberculosis (consumption).

According to the Harvard University Library, tuberculosis was “the cause of more deaths in industrialized countries than any other disease during the 19th and early 20th centuries. By the late 19th century, 70 to 90% of the urban populations of Europe and North America were infected with the TB bacillus, and about 80% of those individuals who developed active tuberculosis died of it. ”

In writing about the disease and its treatment, John Frith notes that one of the first research breakthroughs came in 1865 when “Jean Antoine Villemin, a French military surgeon … observed that soldiers stationed for long times in barracks were more likely to have phthisis [tubercular wasting] than soldiers in the field, and healthy army recruits … often became consumptive within a year or two of taking up their posts.”

Sadly, for Tempest Draubaugh, it was not until 1882 that Robert Koch’s research pinpointed the bacillus which causes the disease and confirmed the highly contagious nature of “the white plague.”

Death and Interment

Ultimately consumed by tuberculosis, Tempest T. Draubaugh finally passed away in Newberry Township, York County, Pennsylvania on 4 January 1874. He was just 32 years old.

Grateful Americans wishing to pay their respects to the former teacher-soldier may do so at the Grand Army of the Republic section of the Paddletown Cemetery in Newberrytown, York County.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5. Harrisburg: 1869.

2. Draubaugh, Tempest T., in Pennsylvania Veterans’ Burial Cards. Harrisburg: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Military Affairs, 1936.

3. Drawbaugh, T. T., in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1865. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania State Archives.

4. Drawbaugh, T. T. or L. L., in Burial Records, in St. Peter Lutheran Church Records, in Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 4 January 1874.

5. Drawbaugh, Tempest, Jacob Drawbaugh and Wife, Samuel Drawbaugh, Rebecca Drawbaugh and Mary Drawbaugh, in Baptismal Records, in St. Michael Evangelical Lutheran Church Records, in Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 12 October 1845.

6. Drawbaugh, Tempest T, in U.S. Civil War Veterans Pension Index (application no.: 106839, certificate no.: 84774). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 1866.

7. Frith, John. History of Tuberculosis. Part 1 – Phthisis, consumption and the White Plague, in Journal of Military and Veterans’ Health, Vol. 22, No. 2. Hobart Tasmania, Australia: Australian Military Medical Association, 2014.

8. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown: Self-published, 1986.

9. Tuberculosis in Europe and North America, 1800-1922, on Contagion: Historical Views of Diseases and Epidemics. Cambridge: Harvard University Library Open Collections Program, retrieved online, 2 April 2016.

10. U.S. Census. Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania: 1850, 1860, 1870.

You must be logged in to post a comment.