Catasauqua, Pennsylvania, circa 1852 (Lambert’s A History of Catasauqua in Lehigh County Pennsylvania, 1914, public domain).

Born in Catasauqua, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania in January 1843, Alfred Lynn was a son of Pennsylvania natives, Robert Lynn (born sometime around 1814) and Caroline Lynn (1818-1899), and the brother of Sarah Elizabeth (Lynn) Young (1842-1916).

In 1850, he resided with his parents in Catasauqua, where his father was employed as a blacksmith; however, his remaining formative years are murky. After his father died (sometime between 1850-1860), he was sent away to live with Walter and Catherine Biery, but resided there without his mother. According to the federal census of 1860, Alfred Lynn was one of three teens who resided on the Biery farm in South Whitehall Township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania at that time. The oldest was described on the census as a male farm laborer, the other as a female housekeeper. All three were unrelated to the couple.

Note: According to Alfred Lynn’s obituary and federal census records for 1870 and 1880, Alfred’s mother, Caroline Lynn, remarried and was then widowed by John Hunsicker.

Three years into America’s great Civil War, Alfred Lynn was described on Union Army enlistment records as a 20-year-old laborer and resident of Lehigh County.

Civil War Military Service

Alfred Lynn enrolled for Civil War military service on 7 December 1863 at the Union’s recruiting center in Norristown, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, and mustered in there the same day as a Private with Company F, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Fort Jefferson, Dry Torguas, Florida (interior, circa 1934, C. E. Peterson, photographer, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Sent by sea to the Deep South, he connected with his regiment on 4 January 1864 at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, Florida, where half of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had been stationed since the late months of 1862.

His new comrades were a hardened-group of veterans. Bloodied during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina (21-23 October 1862), they had also been battered by dysentery and tropical diseases while garrisoning Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Florida (1863).

Military records at the time described him as being 5′ 8″ tall with light hair, hazel eyes and a fair complexion.

1864

On 25 February 1864, Private Alfred Lynn and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanian Volunteers set off for a phase of service in which the regiment would make history. Steaming first for New Orleans aboard the Charles Thomas, the men arrived at Algiers, Louisiana on 28 February and were then shipped by train to Brashear City. Following another steamer ride – this time to Franklin via the Bayou Teche—the 47th joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps. In short order, the 47th would become the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign spearheaded by Union General Nathaniel P. Banks.

From 14-26 March, the 47th passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville, Opelousas, and Washington while enroute to Alexandria and Natchitoches, Louisiana. Often short on food and water, the remaining members of the regiment encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, sixty members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

Casualties were severe. The regiment’s second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel G. W. Alexander, was nearly killed, and the regiment’s two color-bearers, both from Company C, were also seriously wounded while preventing the American flag from falling into enemy hands.

In Company F, Private George Klein was discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate on 16 April 1864. And, after having been shot in the jaw during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (Mansfield), Private Griff Reinert was ultimately discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate on 28 December 1864.

Still others from the 47th were captured by Confederate troops, marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as prisoners of war until they were released during prisoner exchanges on 22 July and in September and November. Private John L. Jones, who was wounded during the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April before being taken prisoner, languished in captivity at Camp Ford until he was finally released during a prisoner exchange on 24 September 1864. Just ten days earlier (on 14 September), while still a POW, he had been promoted by his regiment to the rank of Corporal. He survived the experience, went on to receive another promotion, and mustered out with his regiment in 1865.

But, at least two members of the 47th Pennsylvania never made it out alive. Private Samuel Kern of Company D died at Camp Ford on 12 June 1864, and Private John Weiss of F Company, who had been wounded in action at Pleasant Hill, died from his wounds at Camp Ford just over a month later on 15 July.

Following what some historians have called a drubbing by the Confederate Army and others have called a technical Union victory (or at least a draw), the 47th Pennsylvania fell back to Grand Ecore, where the men resupplied and regrouped until 22 April.

Named “Bailey’s Dam” for the officer ordering its construction, Lt.-Col. Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River in Alexandria, Louisiana (May 1864) eased Union gunboat passage (public domain)

On 23 April, the 47th and their fellow brigade members crossed the Cane River via Monett’s Ferry and, under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, helped to build a dam from 30 April through 10 May, which enabled federal gunboats to successfully traverse the rapids of the Red River.

Beginning 16 May, Captain Henry S. Harte and F Company moved with most of the 47th from Simmesport across the Atchafalaya to Morganza, and then to New Orleans on 20 June.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Still able and willing to fight after their time in Bayou country, the soldiers of Company F and their fellow members of the 47th Pennsylvania returned to the Washington, D.C. area aboard the McClellan from 5-12 July 1864—but they did so without their commanding officer, Captain Henry S. Harte, who was ordered to serve on detached duty as the leader of the 47th Pennsylvanians serving with Companies B, G and K, who were left behind when the McClellan was unable to transport the entire regiment. (Captain Harte sailed later aboard the Blackstone with Companies B, G and K, and arrived in the Washington, D.C. area on 28 July.)

Also during this time, more members of the 47th Pennsylvania were discharged on Surgeons’ Certificates of Disability while others who had been left behind at Union military hospitals to convalesce, died in New Orleans later that summer.

After arriving in Virginia, Private Alfred Lynn and the remaining 47th Pennsylvanians joined up with Major-General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap, where they assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August and reunited briefly under the command of Captain Harte, September saw the departure of several 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who had served honorably, including F Company’s Captain Harte, who mustered out at Berryville, Virginia on 18 September 1864 upon expiration of his three-year term of service. Those members of the 47th still on duty were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill, September 1864

Together with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Philip H. (“Little Phil”) Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company F and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”). The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. After finally reaching and fording the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with Early’s Confederate Army. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

The 19th Corps, with the 47th in the thick of the fighting, then began pushing the Confederates back. Early’s “grays” retreated in the face of the valor displayed by Sheridan’s “blue jackets.” Leaving 2,500 wounded behind, the Rebels retreated to Fisher’s Hill, eight miles south of Winchester (21-22 September), and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union men which outnumbered Early’s three to one. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek.

Moving forward, the surviving members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but they would do so without two more of their respected commanders: Colonel Tilghman Good and Good’s second in command, Lieutenant Colonel George Alexander, who mustered out 23-24 September upon the expiration of their respective terms of service. Fortunately, they would be replaced with leaders who were equally respected for their front-line experience and temperament, including Major John Peter Shindel Gobin, formerly of the 47th’s Company C, who had been promoted up through the regimental staff to the rank of Major (and who would be promoted again on 4 November to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel and responsibility of regimental commanding officer).

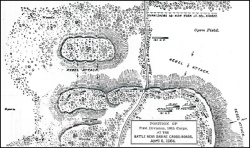

Battle of Cedar Creek, October 1864

It was during the fall of 1864 that Major-General Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents—civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally and win the day.

From a military standpoint, it was an impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles—all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he rode rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

The Union’s counterattack punched Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

Once again, the casualties for the 47th were high. Sergeant William Pyers, the C Company man who had so gallantly rescued the flag at Pleasant Hill was cut down and later buried on the battlefield. Privates Addison R. Geho and Rainey Grader of Company F were killed in action—and Private Alfred Lynn became one of the many who were wounded in action.

After sustaining a gunshot wound to his right leg, he was treated initially at a field hospital; however, the wound was severe enough that he needed more advanced treatment. As a result, he was sent to one of the Union’s larger general hospitals in Baltimore, and evidently remained there until being discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability on 14 October 1865—nearly a full year after being wounded in action.

Return to Civilian Life

Following his honorable discharge from the military, Private Alfred Lynn returned home to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley. On 16 April 1870, he wed Pennsylvania native Mary Borger (1847-1902) in Schoenersville, Lehigh County.

Together, they welcomed to the world four children:

- Ellen E. Lynn: Born in Catasauqua, Lehigh County on 15 January 1872, she married and raised a family with Walter H. H. Hindle (1857-1930) before passing away in Catasauqua on 6 May 1927, and being laid to rest at the Fairview Cemetery in West Catasauqua;

- Emma J. Lynn: Born in Catasauqua sometime around 1874, she remained unmarried as of 1930;

- Harvey Robert Lynn: Born in Catasauqua on 23 January 1876, he was employed as the manager of Dorney Park in 1910 before embarking on a career as a movie projectionist at the Lehigh Orpheum Theatre and the Earle Theater. Succumbing to complications from heart disease on 23 October 1952 at the Allentown Hospital, he was laid to rest at the Allentown’s Grandview Cemetery; and

- Anna Lynn (“Annie”): Born in Catasauqua on 3 October 1879, she greeted the arrival of son Rhuel Clawason in April 1898, and later wed and was widowed by Abraham Leith (1874-1933) before succumbing to complications from heart disease and diabetes on 16 January 1939 in Hellertown, Northampton County, Pennsylvania. She was then laid to rest there at the Union Cemetery.

Alfred Lynn supported his family as a contractor who provided painting and paper hanging services to customers across the Lehigh Valley.

Shortly before the turn of the century, on 3 October 1899, Alfred Lynn’s twice-widowed mother passed away in Catasauqua. She was 81 years, 4 months and 25 days old. The Allentown Leader reported her death in its 5 October edition as follows:

Died at Catasauqua

Mrs. Caroline Hunsicker, one of the oldest residents of Catasauqua, died on Tuesday of a complication of diseases. She had been ill for some time. She is survived by two children, Mrs. Thomas Young and Alfred Lynn. Mrs. Lynn was twice married her first husband being a Mr. Lynn. The funeral will take place to-morrow [Friday, 6 October 1899] at 9 a.m. from the residence of her daughter, Mrs. Thomas Young, Fifth Street above Walnut. Services will be held at the house and interment made in Fairview Cemetery, Catasauqua. Rev. J. D. Shindel will officiate.

When her will was read, Alfred Lynn learned that he would received just $1.00 from his mother’s estate:

As to the residue of my property I make the following disposition. As I have already given money to my son Alfred Lynn I give devise and bequeath to him the sum of one dollar. To my Grand daughter [sic] Elmira Fehr I give and bequeath the sum of one hundred and fifty dollars. To my daughter Sarah Elizabeth Young I give and bequeath the balance and residue of my estate. As Executrix of my will I appoint and constitute my Grand-daughter Elmira Fehr….

Elmira M. Fehr (1865-1934), the executrix of Alfred’s mother’s estate, was Alfred Lynn’s niece. Born on 24 October 1865, she was a daughter of Thomas B. and Sarah Elizabeth (Lynn) Young and the wife of Benjamin Fehr (1865-1945). All were buried at the Fairview Cemetery in West Catasauqua, Pennsylvania.

Alfred Lynn clearly experienced financial challenges during the decade leading up to his mother’s death—possibly from legal actions which had been taken against him (trial listings for Lydia Kieffer v. Alfred Lynn, commencing 26 January 1880 and commencing 24 January 1881 in The Allentown Leader), but those difficulties appear to have been resolved because later newspaper reports show him as a respected Civil War veteran engaged in local civic and social activities.

Mess Hall, Mountain Branch, U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Johnson City, Tennessee (circa 1903, public domain).

A widower by 1905 with lifelong health issues arising from his Civil War military service, including lumbago, a hernia, and complications from the gunshot wound he sustained to his right leg, he was admitted to the U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers’ Mountain Branch in Johnson City Tennessee on 17 March 1905. He received a pension of $17 per month, and remained at that facility until he was discharged at his own request on 15 February 1910.

Retired from his contracting business, he resided at the home of his son Harvey, who supported his wife, Hannah, through employment as a “Solicitor, Theater.”

Death and Interment

Ailing from Bright’s disease, Alfred Lynn suffered an attack of dropsy, and passed away at the Lehigh County Soldiers’ Home in South Whitehall Township on 19 July 1910. The 21 July 1910 edition of The Allentown Leader reported his passing as follows:

DEATH OF ALFRED LYNN, CIVIL WAR VETERAN.

LIFELONG RESIDENT OF CATASAUQUA SUCCUMBS TO ATTACK OF DROPSY.Alfred Lynn, a lifelong resident of Catasauqua and Civil War veteran, died yesterday after a lingering illness with dropsy, aged 65 years. He was born in the Iron Borough and was in the painting and paperhanging business for many years.

During the Rebellion he served as a private in Co. F, 47th Regiment Penn’a Volunteers, under Captain Henry S. Harte, and took part in a number of engagements with that regiment. He was mustered into the service Dec. 7., 1863, and honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate Oct. 14, 1865.

Mr. Lynn’s wife preceded him in death eight years ago. He is survived by one son, Harvey R. Lynn, manager of Dorney Park; three daughters, Mrs. W. Hindele and Miss Emma Lynn of Catasauqua, and Mrs. A. Leith of Hellertown; one sister, Mrs. Thomas Young, of Catasauqua, and a step brother, Martin Hunsicker of Bethlehem.

Funeral services will be held on Friday at 10 a.m. in the Fairview Cemetery Chapel, West Catasauqua, followed by interment in the family plot.

He was laid to rest at the Fairview Cemetery in West Catasauqua, Lehigh County. The Allentown Leader gave this brief recap of his funeral in its 22 July 1910 edition:

The funeral of Alfred Lynn, the Civil War veteran, who died on Tuesday, was held this morning and was well attended. Rev. A. P. Frantz, pastor of Salem Reformed Church, conducted the services in the Fairview Cemetery Chapel. Interment followed in the family plot.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

2. Civil War Muster Rolls, in “Records of the Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs” (Record Group 19, Series 19.11). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

3. Civil War Veterans’ Card File. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

4. Death Certificates (Alfred Lynn, Elizabeth Young, et. al.). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics, 1910.

5. “Death of Alfred Lynn, Civil War Veteran: Lifelong Resident of Catasauqua Succumbs to Attack of Dropsy. Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 20 July 1910.

6. Hunsicker, Caroline (Last Will and Testament, Probate Place: Northampton, Pennsylvania), in “Will Books, 1752-1907; With Register’s Index, 1752-1966.” Northampton County, Pennsylvaia: Office of the Register of Wills, 1899.

7. Lambert, James F. and Henry J. Reinhard. A History of Catasauqua in Lehigh County Pennsylvania. Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Searle & Dressler Co., Inc., 1914.

8. Lynn, Alfred and Mary Borger, in Christ Reformed Church Marriage Records, in “Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records.” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

9. Lynn, Alfred, in “Catasauqua” (funeral report). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 22 July 1910.

10. Lynn, Alfred, in “Deaths” (funeral notice). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 21 July 1910.

11. Lynn, Alfred, in Pennsylvania Veterans’ Burial Cards, 1910. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs.

12. Lynn, Alfred, in Admissions Ledgers, U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (Mountain Home Branch, Johnson City, Tennessee), 1905-1910. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

13. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

14. U.S. Census 1880. 1850, 1900, 1910. U.S. Vets’ Schedule: 1890. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Naional Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.