Oh dear Stephen, there is no night that I lay my troubled head on my pillow that I do not wish you lay in that bed too, and think of these tears that I have shed since you are gone.

Oh dear Stephen, there is no night that I lay my troubled head on my pillow that I do not wish you lay in that bed too, and think of these tears that I have shed since you are gone.

— Mary B. Moyer in a letter to her husband, Private Stephen J. Moyer, 1862

Kind. Empathetic. Genial. A man with a “legion of friends.” That was how the people encountered by this native son of Pennsylvania came to view him during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

His beloved wife, Mary Barbara (Nyhart) Moyer, was also greatly respected by those who knew her. Eulogized upon her passing as “a consistent and loving Christian spirit,” she was further described as “a wise, resourceful, and indulgent mother,” who had not only been a companion to her husband during “his early trials,” but “a brave helper in all his hard problems and heavy labors, a wise counsellor, and the truest and best earthly friend he [had] ever known.”

Formative Years

Born in Plainfield, Northampton County, Pennsylvania on 26 July 1833, Stephen J. Moyer (1833-1915) was a son of Jacob Moyer and Maria (Knecht) Moyer. A resident of his county of birth for two decades, Stephen began his own family on 10 September 1857 in Nazareth, Pennsylvania when he wed Mary Barbara Nyhart (1837-1901). A native of Kellersville, Monroe County, Pennsylvania, she was a daughter of Simon and Elizabeth Nyhart, longtime residents of that county.

In short order, the duo became a trio when their son, Frank M. Moyer (1858-1912), was born in Easton, Pennsylvania on 31 March 1858.

Trained in Tannersville as a gunsmith sometime prior to or during the early months of his marriage, Stephen Moyer abandoned the trade soon after when a process for the mass production of firearms began limiting his options for stable employment. By 1860, he and his wife and son were living in Scranton, Pennsylvania, where he had found work with the Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company.

A year later, daughter Ella C. Moyer (1861-1883) was born in Scranton on 10 May 1861—a ray of sunshine for parents who watched and worried as disunion between America’s North and South boiled over into civil war.

Civil War Military Service

On 13 January 1862, Stephen J. Moyer joined the fight to preserve America’s Union. Leaving his wife and two young children behind, he enrolled for service that day at Easton, Pennsylvania, and then officially mustered in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg as a private with Company A of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Military records at the time described him as a 26-year-old, 5’8”-tall farmer with sandy hair, gray eyes, and a fair complexion.

He had enlisted just in time to join his new comrades for departure to America’s Deep South on a critical mission launched by Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan—an expedition to secure and maintain control of key military forts located throughout Florida in an effort to prevent the ‘Confederate States of America from using those forts to receive and redistribute ammunition, weaponry, food, and other supplies to CSA Army and Navy forces throughout the southern United States.

After arriving at the 47th Pennsylvania’s headquarters at Camp Griffin, Virginia on 17 January, he had less than a week to acquaint himself with the members of his regiment. His unit—Company A—was commanded by Captain Richard A. Graeffe, who had emigrated from Germany in 1847 and had become one of the first men to answer President Abraham Lincoln’s April 1861 call for 75,000 troops to help quell the South’s burgeoning rebellion following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces.

By the early morning of 22 January, Private Stephen Moyer and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were lined up and ready to move out with their regiment. After listening to the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band play “Auld Lang Syne” and giving “three cheers for Camp Griffin, they began their march at 8:30 a.m., slogging through snow and deep mud for three miles in order to reach the Vienna railroad depot in Falls Church, Virginia. Arriving at 9:30 a.m., they boarded a train and departed at 11 for Alexandria, Virginia where, a half hour later, they marched behind their band to the strains of “Yankee Doodle.”

The City of Richmond, a sidewheel steamer which transported Union troops during the Civil War (Maine, circa late 1860s, public domain).

Arriving at the docks nearby, they quickly began loading their equipment on the City of Richmond, a steamship which ultimately transported them along the Potomac River to the Washington Arsenal, where they disembarked sometime around 4 p.m. Marched from the arsenal area’s docks to the munitions storage area, regimental leaders replenished the ammunition supplies of the regiment, one company at a time—a process which took roughly two hours. They were then marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C.

The next day (23 January), the 47th Pennsylvanians boarded a Baltimore & Ohio Railroad train. Departing for Annapolis, Maryland at 2 p.m., they arrived around 10 p.m., were assigned quarters in barracks at the U.S. Naval Academy, and turned in for the night. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship, S.S. Oriental.

Those preparations ceased on Monday, 27 January, at 10 a.m., however, in order to make time for a very public dismissal of one member of the regiment—Private James C. Robinson—who was dishonorably discharged from the 47th Pennsylvania. According to regimental historian Lewis Schmidt and letters home from members of the regiment:

The regiment was formed and instructed by Lt. Col. Alexander ‘that we were about drumming out a member who had behaved himself unlike a soldier.’ …. The prisoner, Pvt. James C. Robinson of Company I, was a 36 year old [sic] miner from Allentown who had been ‘disgracefully discharged’ by order of the War Department. Pvt. Robinson was marched out with martial music playing and a guard of nine men, two men on each side and five behind him at charge bayonets. The music then struck up with ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the procession was marched up and down in front of the regiment, and Pvt. Robinson was marched out of the yard.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were transported to Florida aboard the steamship S.S. Oriental in January 1862 (public domain).

Reloading then resumed and, that same afternoon (27 January), Private Stephen Moyer and the enlisted members of the 47th Regiment, Volunteer Infantry began to board the Oriental, followed by their superior officers. Ferried to that steamship by smaller steamers, they sailed away for America’s Deep South at 4 p.m., per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan. Their ship, which was captained by Benjamin F. Tuzo, was rocked by rough seas for much of their trip; consequently, many members of the regiment suffered from intense seasickness—particularly as the Oriental made its way down the stormy coast of the Carolinas and passed the Bahamas and Great Abaco Island.

On 2 February, Regimental Chaplain William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock gathered his flock together for Sunday services, which began with the tolling of the ship’s bell at 11 a.m., a selection of hymns performed by the Regimental Band, and an opening prayer and scripture reading by Rodrock. Following the regiment’s singing of “From All That Dwell Below the Skies” (accompanied by the band to the music of “Old Hundred”), Rodrock presented that week’s sermon, which was based on the Bible’s “Acts of the Apostles,” chapter 17, verse 23. The service then closed with the singing of “Lord Dismiss Us with Thy Blessing” and the Doxology, followed by Rodrock’s benediction.

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Arriving in the waters off Key West, Florida at 8 p.m. on Monday, 3 February, the 47th Pennsylvanians were forced to endure a waiting game aboard ship until a pilot could be brought aboard to bring the ship into a safe place in the harbor—a process the pilot began at 7 a.m. the next morning.

According to Schmidt, “The deck was crowded with the regiment’s men, with the band playing as they passed some of the men-at-war…. Arriving in the harbor at 8 AM, the bands playing ‘national songs’ and numerous onlookers, including many ‘colored women,’ along the shore watching the ship sail into port.”

After disembarking at 9 AM on the dock about one mile west of Fort Taylor, the regiment marched down the main street of the city in their regular order of column of divisions, and stacked their weapons, waiting until the unit would be notified where to make camp…. At 12 in the afternoon, the men were ordered to fall in and stand to attention, and with their 23 member band playing and the ladies of Key West waving their handkerchiefs, and with quite a crowd of followers, the 1000 men marched to their new camp ‘one fourth mile out of the city, near the beach,’ across from the barracks of the 90th New York Regiment.

Led to the area of Key West that is now known as Palm and White streets, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were, in fact, initially housed just 350 feet from the ocean in early 1862. Their first nights were “spent in blankets on the beach, with knapsacks for pillows”—a vexing, sandy state of affairs which persisted until their tents were unloaded and assembled on Thursday, 6 February.

Even so, the members of the regiment still managed to make an early, favorable impression on Key West residents, including a New York Herald reporter who “commented on the fact that the 47th was equipped with the best weapons available, and was the best looking Volunteer Regiment he had ever seen.’’

Attached to the command of Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan and assigned to garrison Fort Zachary Taylor in Key West, Florida in early February 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were soon brought face to face with the realities of life behind enemy lines in America’s Deep South as the United States was about to enter into the second year of its Civil War. Taking turns with members of Brannan’s other regiments (the 90th and 91st New York Volunteers) in guarding roughly 200 to 300 blockade runners, gunboat operators and other Confederate prisoners, as well as 57 secessionists from Ship Island, they also drilled daily in heavy artillery tactics, felled trees, helped to build new roads, and strengthened the fortifications in and around the Union Army’s presence in Key West.

* Note: Although several earlier historians have speculated that the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry was ordered to Florida because its members were incompetent militarily or because they were being punished for some unspecified wrongdoing, this belief is unfounded. Brigadier-General Brannan personally selected the 47th Pennsylvania to accompany him on what he knew would be a difficult mission—terminating Florida’s role as “the supplier of the Confederacy.” Florida’s livestock farmers were among the earliest to feed Confederate States Army troops, becoming one of the largest sources of cattle for CSA regiments, as well as suppliers of pork products while other food producers contributed fruit and fish. In addition, Florida was a major producer of American salt—a key ingredient critical to the preservation of food for CSA troops on the move.

As the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers settled in further to their new assignments, Brannan’s men also began to make their presence felt in another important way—by trooping regularly at the fort and through the town. On Friday, 7 February, Private Stephen Moyer and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians marched behind their Regimental Band in three separate regimental parades, followed by an evening drill in front of their barracks.

To safeguard against potential misbehavior by soldiers stationed far from home, military discipline was also instilled through a series of proclamations by superior officers at the brigade, regimental, or unit levels, such as General Order No. 2, which announced that water permits would be “issued to the quartermaster Sgt. of each company each evening at 6:45 for the succeeding day” due to a critical shortage of safe drinking water:

A sufficient number of men will be detailed to carry water, but they will not be excused from other duty. No bathing will be allowed after 5:30 AM. The right wing of the regiment will bathe tomorrow morning from 5 to 5:30 AM. They will be in charge of a commanding officer of each company. The commanding officer will see that the men avail themselves of bathing as it is essential to the health and welfare of the regiment. All bathing in daytime is absolutely prohibited.

Hours of service and roll call are: Reveille at daybreak; police immediately after; call for drill 5:30; recall 7; breakfast 7:15; surgeon’s call 7:45; guard mounting 9; call for drill 10; recall 11; dinner 12; 1st Sgt. call 1; call for drill 3:30; recall 5; dress parade 5:30; tattoo at 8; taps 8:30. These calls will be beat by the drum at the central guard quarters five minutes before the time stated.

Special Order No. 18 authorized Captain Graeffe, Company A’s commanding officer, to redirect two men to the regiment’s master baker for extra duties as bakers’ helpers.

Following an early inspection by their superiors on Sunday, 9 February, many 47th Pennsylvanians walked into the city to attend church services. C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton described the experience a week later in another of his letters to the Sunbury American:

With several members of our company I attended Episcopal Church last Sabbath—The church building is a large and beautiful one, and the people deserve great credit for erecting it. The Minister is a strong Union man, and it struck me, on last Sabbath, that he lost no opportunity of displaying his Union sentiments. Some time ago some members of the Church were very disloyal, and when the Minister read the prayer “to behold and bless Thy servant, the President of the United States, and all others in authority,” they would close the prayer book, and look daggers at him, wondering whom they should hang first—the Minister or Abe Lincoln. General Brannan (Captain at the time), hearing of it, put an end to this disrespect, made them take the oath of allegiance, and they now can say ‘Amen’ as loud and as heartily as the best Union men on the island…. For the sake of the Church, I am happy to state that only a few of its members were weak enough to show their fondness for Jeff Davis—the rest of the members were very glad that Gen. Brannan took the matter in hand.

The population of the island is about four thousand, consisting of negroes, Spaniards, and a few whites. With the exception of five storekeepers, the occupation of its inhabitants is fishing, dealing in fruit and selling hot coffee and cool drinks…. As for intoxicating drinks, they are prohibited—the island being under martial law it is impossible to get even a smell, and it is well that it is so, for in this climate there is no telling what amount of sickness its use might produce…. Oranges, coming from Cuba and Nassau islands, are very plenty, and can be bo’t [sic] at three for a sixpence; not such as you folks get at home, but real fresh, juicy fellows that melt in one’s mouth equal to the best ice cream made in H. B. Masser’s patent ice cream freezers. Fish are very plenty, and can be bought cheap. Thanks to Sergeant Smelser [alternate spelling “Smeltzer”], our company is living high in the fish line. He is Company Quarter-Master Sergeant, and on every fish market morning, Peter is at the wharf, and there exchanges our surplus pork and beef for fish; so that the boys have a variety and are content….

There is an article here, that I believe bothers the whole human race, and that is mosquitoes. Those on this island are not of the common kind, but regular tormentors. — Fix your net work as you may, you will receive their sting before morning….

The Fort on this island (Fort Taylor) is a very large one, and is now of the most importance to the Government. It is not near finished, but so much so that the rebels dare not venture within the range of its guns. — When finished it will have one hundred and eighty guns, and with those on the embankment on the moat, fronting the town, it will have two hundred and seventy five. Some time since the fort came within an ace of being taken by the rebels, but Capt. Brannan saved it by stratagem. Men were working at the fort, so, to prevent suspicion, the Captain every morning would march a guard from the garrison to the fort, and in that manner before the rebels were aware of it, he had full possession of it. Mulraner, formerly a Sergeant of the Captain’s, who became rich in the rum business, hoisted a secesh flag on his hotel, and sent an impudent note to the Captain requesting him to honor the seven stars by firing a salute from the fort. The reply was that if the rag was not taken down on the return of the messenger, the Commander would open the guns of the fort on the town, and send Mulraner and his friends to Tortugas to work in the hot sand and give them time to repent of their folly, preparatory to dangling at the end of a rope. The flag was taken down—Mulraner vamoosed [sic] the ranch, and is now in command of a company of rebels somewhere near Pensacola. It is tho’t [sic] that when Gen. Brannan arrives Mulraner’s property, which is valuable, will be confiscated….

You need not be surprised to here [sic] of an expedition being sent out from here—everything looks like it—so many vessels in port, more expected and troops arriving every day. There are three regiments here now, the 90th and 91st New York, and our own, besides the Regulars in the fort. If we do go, there will have to be a strong force left behind; for, in my opinion, the most of the Union men here are as treacherous as the men who use the stiletto to stab a friend, at night, from behind….

Sibley Tent (Patent #14740, United States Patent Office, 22 April 1856, H. H. Sibley, public domain).

As the days of February rolled by, the commanding officers of the 47th Pennsylvania made a concerted effort to stabilize the living arrangements for their subordinates, housing the bulk of their men in barracks southeast of Palm Avenue and White Street at Peary Court on the eastern side of Key West. Lodged in three buildings on the northeast side and three buildings on the southwest side of the Union Army’s parade grounds were the regiment’s field and staff officers, as well as the entire membership of the Regimental Band. Additionally, two 125-foot by 20-foot buildings accommodated a portion of enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania with the remainder housed in adjacent military tents—effective Tuesday, 18 February. Known as Sibley tents, these were large, round, canvas structures which were 12 feet tall by 18 feet in diameter, supported by center poles and warmed by central fireplaces. Housing 16 to 19 men each, seven tents each were erected by the 47th Pennsylvania’s ten companies. One tent per company was placed at the head of each company’s “street” to house that company’s officers with the other six tents per company allotted to the enlisted men, each of whom who were arranged on the inside “like the spokes of a wheel,” according to Schmidt, “with their feet to the fireplace.”

There were also a significant number of enslaved and formerly enslaved men, women and children in the region. According to Schmidt:

There was a slave camp about one mile from the military camps, where 150 Blacks were engaged in manufacturing salt; it was reported that 50,000 bushels of salt were made on the island each year by solar evaporation…. The manufacture of salt was terminated later in 1862, and was not restarted until 1854, to prevent any salt from the facility finding its way into the Confederacy….

Another building of note on the island of Key West during the war was the ‘slave barracoons’, used to house Blacks taken from captured slavery vessels, and described as being a long low building about 300 feet by 30 feet. Lt. Geety reported that there were 1500 slaves there at one time, and 400 died in four months [sic] time; a rate per day that the 90th New York Regiment would approach in August-September as a result of a Yellow Fever epidemic, during which time the barracoons, located at Whitehead’s Point in the southernmost area of Key West would be converted into a temporary hospital.”

On Friday, 14 February, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers made their presence known once again to Key West residents as the regiment paraded through the streets of the city. Two days later, their commanding officers insisted that they attend services at local churches. That same evening, a man entered the camp to request protection. Provided food and a tobacco-filled pipe, he was also given a regimental uniform to replace his tattered, soiled clothing. His mind at greater ease, he then explained that he had escaped slavery from Providence Island, and recounted his life experience to one of the regiment’s bilingual members, who documented the man’s story in German. The following translation was provided by regimental historian Lewis Schmidt:

My name is Walter Bowten and I was born in 1835. My parents were born slaves but they worked to free themselves. I was a servant until I was 13 years old and then my master put me into the field to make sugar and molasses. I tried to escape, but my master came on the ship and took me back…. Where my master lives is not much of a place, it is only one island where tangerines, oranges, lemons and coconuts grow. I do not have a cent of money from my master and would rather be with the white folks than with a mulatto. I had to work every day from morning until night, and on Sunday we had to work until 8 in the morning. We had two changes of clothing, one for work and one change for good, and when the clothing was torn, our master would threaten and whip us. Our master would not let us go to the soldiers and said he would shoot us, but we came away anyway.

Regrettably, the attempts of the 47th Pennsylvanians to protect Bowten were thwarted the next day by other soldiers at the fort who seized Bowten while the 47th was marching in another of its regimental parades. Bowten was subsequently ordered to be held at the fort, according to Schmidt, “until a ship which had gone to Havana for a load of sugar would return.”

On Friday, 21 February, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in a dress parade observed by Brigadier-General Brannan, who had just arrived at Fort Taylor that day. Brannan later took the time to ride his horse along the various “company streets” of the 47th’s encampment, “tipping his hat” as he passed his cheering subordinates, according to Schmidt.

Another brigade parade was then held at 10 a.m. the next day—Washington’s Birthday—a day of great joy that began with prayer and a reading of President George Washington’s farewell address.

The parade began with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry and the other units commanded by Brannan marching through Key West to the home of a Union-supporting judge who was known for proudly flying the American flag. Stopping behind its Regimental Band as it struck up “The Star-Spangled Banner,” the 47th Pennsylvania then marched to Fort Taylor, where its members witnessed the firing of a national, 34-gun salute by the fort’s artillery guns, followed by a salute fired by the guns of the man-of-war, Pensacola.

The celebration continued well into the evening, as brigade members were treated to a band concert and formal address by C Company Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin. Brigade members then competed against one another in foot, wheelbarrow and sack races, as well as a pig chase. C Company Colonel Jacob K. Keefer came in second in that foot race while C Company Private P. M. Randall finished second in the sack race after falling near the end and rolling across the finish line.

On Monday, 24 February and Wednesday, 26 February, the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band again performed in concert with the ensemble giving “a ball for the officers, which was “numerously attended by the Knights of the spur and tinsel,” according to Wharton, who also noted that “there were only enough ladies in attendance to form six setts.”

On Friday, 28 February, the entire regiment reported for an 8 a.m. inspection in response to Regimental Order No. 39, issued by the commanding officers of the 47th Pennsylvania per Brigadier-General Brannan’s General Order No. 5. The regiment also received the following instruction via Brannan’s General Order No. 11:

I. Officers and soldiers are required to live within the limits of their respective commands and on no account to sleep out thereof without special permission of the Brigadier General commanding. No non-commissioned officers or soldier will be allowed in the town without a written pass from his commanding officer. Non-commissioned officers furnished with permits from their commanding officers will be allowed in town. But the provost guard has strict orders to arrest any Private who on any pretext is found in town after the tattoo beating [the signal from regimental musicians that lights should be extinguished and all loud talking or other noise should cease within 15 minutes when Taps will be played] except by special permit from headquarters.

II. The attention of commissioned officers is specially directed to article 29, paragraph 237 to 257 relating to: Honor to be paid by the troops. Any non-commissioned officer or soldier when approaching a commanding officer will invariably salute, if armed by touching his musket at the position of shoulder arms, if unarmed by raising the outer hand horizontally to his cap peak. Should the officer address him he will stand in the respectful position of attention until the officer shall have concluded. On an officer entering the quarters of any party of non-commissioned officers, the senior officer will call the party to attention; and on his approaching any party of men commanded by a non-commissioned officer they will immediately be called to attention and if armed brought to the position of shoulder arms. Should an officer approach any soldier or party of soldiers sitting or lying down they will immediately rise and remain in the position of attention until he shall have passed…. A sentry on post on the approach of an officer will first halt, second face outward from his post, third come to the position of shoulder arms. Should the officer prove to be a general or field officer he will further come to the position of present arms and so remain at the requisite salute until the officers shall have passed his post. The sentry on the guard room door of all guards will turn out his guard at the approach of the general commanding, the field officer of the day, and all armed parties. Regimental guards will further turn out to the commanding officer of their respective regiments….

III. No officer or soldier on guard duty will leave his guard room on any business whatever without being fully equipped. Neither will any soldier be permitted to leave the camp or station of his regiment or company unless properly dressed in accordance with the regulations of that headquarters.

IV. Public property is on no account to be used otherwise then in the service of the government nor will any soldier be permitted to act as an officer’s servant unless he be duly mustered as such….

Throughout March and April, typhoid fever, bilious fever, and chronic diarrhea ravaged the ranks of the 47th Pennsylvania, resulting in multiple burials at the post cemetery for those who died and multiple discharges of men on certificates of disability for those who survived but were so weakened by their individual battles that they were deemed no longer fit to serve. Even the regiment’s founder and commanding officer—Colonel Tilghman H. Good—fell ill.

Suffering then intensified in early May when the weather became so hot and dry that leaves of trees turned yellow and mosquitos grew more bothersome. In response to the worsening shortage of safe drinking water, Brannan and his subordinates ordered a distilling machine from New York to enable his troops to distill sea water.

By the third week of May, Good, who had quarantined himself in a private home in Key West, was well enough to return to his command. In response, the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band gave a brief, impromptu “welcome back” concert in Good’s honor on 22 May.

On Friday, 13 June 1862, Private Stephen Moyer and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were informed, via General Order No. 53 issued by Brannan, that they needed to hold themselves “in readiness for immediate embarkation,” and that each regiment would be required to take six months’ “supply of medicine and medical stores on embarkation.” Rumors spread that the 47th Pennsylvania would move to Port Royal, South Carolina, and would likely “be present at the taking of Charleston or Savannah.”

The next day, Brannan personally reviewed his assembled troops. According to a report in the New Era:

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers under command of Lt. Col. Alexander made a fine appearance. Their marching was perfect and the entire regiment showed the effect of careful drill. A more sturdy, soldierly looking body of men cannot be found, probably, in the service. Col. Good and the officers under his command have succeeded in bringing the regiment to a state of military discipline creditable alike to them and the state from which they hail….

Three days later, the 47th Pennsylvania began its staged departure with the men from Companies A, F and D setting sail aboard the schooner Emilene on Tuesday, 17 June. Companies B, C, and I sailed aboard the brig Sea Lark to Hilton Head from 17-18 June while Companies E and H sailed away at 10 p.m. on 19 June, and Companies G and K departed aboard the sloop Ellen Benan at 2 PM on Friday, 20 June—the same day that yellow fever descended upon the city of Key West.

Shortly after their arrival in South Carolina, Private Stephen Moyer and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers learned that Major-General David Hunter had, prior to their departure from Florida, successfully launched a bold, new military initiative—recruitment at Hilton Head Island of the first regiment to enroll only Black enlisted men. Dressed in dark blue uniform coats, blue uniform trousers (which were later exchanged for red trousers), cotton shirts, and cone-shaped hats with broad brims, the 300-member unit was commanded by white officers, but then disbanded in August due to Hunter’s failure to pay the men. (According to Schmidt, one company of these Black soldiers was able to be saved; it “remained in service on guard duty at St. Simon’s Island, and later became the core of the 1st Colored Regiment which had the distinction of being the longest continuously serving colored regiment in the Union Army.”)

Their daily schedule in South Carolina resembled what they had experienced while their regiment was stationed in Florida, according to Schmidt: “Reveille at sunrise, breakfast immediately after, surgeon’s call at 6 AM, first call for drill at 6:10, second call at 6:15, morning reports at 7, recall from drill at 7:15, first call for guard mounting at 7:30, guard mounting at 8, dinner at 12, first call for drill 5 PM, second at 5:30, drill to terminate with dress parade at 6:30, tattoo at 9, and taps 9:30” with guards assembling on the parade ground by 7:10 in the morning.”

Bay Street Looking West, Beaufort, South Carolina, circa 1862 (Sam A. Cooley, 10th Army Corps, photographer, public domain).

Departing from Hilton Head on 1 July, Companies A, C, D, F, and H of the right wing of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Beaufort the next day. Companies, B, E, I, and K of the left wing left joined them there the day after, arriving at 6 p.m. The men of D Company were then detached and stationed at Seabrook on the northwestern part of Port Royal Island, roughly two miles southwest of the Port Royal Ferry while B Company men were assigned to picket duty at the ferry during July and August. During this time, the 47th Pennsylvania was part of a brigade that included the 6th Connecticut, 7th New Hampshire, and 8th Maine regiments.

They were prohibited from entering Beaufort without passes—only two of which were available per company each day. Marched to the island’s north side for bathing after sunset on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays, they were subject to inspection every Sunday at 7 a.m. Each man carried 40 rounds of ball cartridge in his cartridge box.

Meanwhile, Stephen Moyer’s wife kept the home fires burning back in Scranton, and prayed—often. On 8 July 1862, she wrote the following letter to her husband:

Meanwhile, Stephen Moyer’s wife kept the home fires burning back in Scranton, and prayed—often. On 8 July 1862, she wrote the following letter to her husband:

Dear Husband,

I have now sat down to answer your letter that I received on the seventh, and it found us all well but Elle, who is not very well. She has the summer complaint very bad, however I am very glad that you are well again. I have been very uneasy about you these few weeks when I heard that you left Key West, and I am afraid that you will come to battle at Richmond, but if you will I hope that there is one mightier there who will keep you from danger so you can return to me again.

I have not received that box, yet, and will let you know as soon as I get it. I have written two letters to you since I received the last one from Key West. I wrote one letter on the 26th and one on the 29th of last month and I enclosed three stamps in the last one. I would send you some with this letter, but I can’t go to town to buy more. But I will write again before long, and then I will send you some. Try and get a furlough and come home once more to see us. You are gone six months already and how many more you will be gone no one can tell, dear Stephen. I hope that this war will not last very long so you can soon come home, but if it is as [illegible; possibly Israel?] tells to all in Scranton, you will not come then. He has said that you told him only two days before you went off that you would get rid of me one way or the other; that you was going to war and then you was rid of me; but I will not believe him that you said it. He makes us all feel as low as he can. Rebecca is going to leave him this week. He is so ugly to her and the children that she can’t stand it anymore with him.

Frank is not at home these two weeks. He is up at Lydia’s [the Lake Winola home of Mary’s sister, Lydia (Nyhart) Smalser] and will be very glad when we get that money that you have sent to have our likeness taken to send to you. Then I want you to send me yours so that I can see how you look in your soldier clothes.

Oh, you do not know how bad I want to see you. I do not see how you can stay away. Oh dear Stephen, there is no night that I lay my troubled head on my pillow that I do not wish you lay in that bed too, and think of these tears that I have shed since you are gone. Oh Stephen, I do not believe that there is another such young person in the world who has had as much trouble as I have had since you are gone. I hope that the trouble will soon be at an end. I have worked for days at hoeing corn and potatoes and we are going to commence haying next week. It will help, but I can’t hardly stand it but I must dear Stephen. I want you to tell me whose likeness it was that you sent to me; and that ring was too small for Frank, and Elle had it on her finger and broke it.

Dear Stephen write as often as you can. I will get you some stamps and send them to you and then write to me every week. I will, too. And now I will close for this time. No more from your true and faithful wife,

Mary

PS Excuse all bad writing and spelling, for the tears come too freely to write good. Now goodbye until I can see you kiss this spot for your wife and children. Come home, oh come home once more.

* Note: Elle Moyer, who was just 14 months old at the time her mother was writing this letter, was suffering from severe diarrhea (often referred to at the time as the “summer complaint”). The child had contracted cholera from contaminated water that mothers in the region had been using for drinking and bathing for their children.

On Thursday, 10 July, Companies B and H engaged the enemy while on picket duty. According to Wharton:

That portion of our regiment to whom was assigned picket duty, on the line nearest the enemy, have returned, being relieved by the 7th New Hampshire Volunteers. Our fellows report the duty pleasant, as it was amusing to see the Georgia sharpshooters trying to pop the pickets on post, forgetting that our Springfield rifles were of longer range than theirs, however, they soon discovered it, as could be seen by the way they jumped behind trees whenever our boys returned their fire. Before our party were relieved, two of three companies crossed the river to have some fun, the rebels not liking the appearance of our bright barrels, skedaddled leaving our men nothing to do but burn down the houses they had for protection, and the pay for their trouble amounted to a few red cotton overcoats.

On Sunday, 13 July, Sergeant Reuben S. Gardner of Company H described a recent stint on picket duty near the Port Royal Ferry in a letter to his father:

We have been on picket now ten days and were to be relieved tomorrow; but for some cause are now to stay five days longer. The general rule is ten days; but always whip the horse that pulls the hardest. We are ten miles from camp, and are picketing around the west end of the island, for 12 miles along the shore. Five companies of our regiment are out at a time. The rebel pickets are right opposite to us, across the river, and dozens of shots are exchanged every day; but without any effect on our side. The rebel’s guns fail to reach across. Our rifles will shoot across with a double charge, but we only fire at each other for fun. The 7th New Hampshire Regiment were on here before we came out and the rebels made them leave the line. They took advantage of that and crossed over and burnt a ferry house that stood on the end of the causeway on this side….

By the end of July, Brannan’s troop strength at Beaufort totaled 5,170—only 4,131 of whom were well enough to be present for duty, thanks to the reappearance of their old foe—disease.

Capture of Saint John’s Bluff, Florida and the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

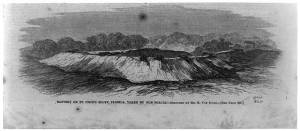

J. H. Schell’s 1862 illustration of the earthworks surrounding the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff above Saint John’s River, Florida (public domain).

Beginning 30 September, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments prepared for the capture of Saint John’s Bluff, which took place from 1 to 3 October. Led by Brigadier-General Brannan, a 1,500-plus force disembarked at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek from Union ships. Forcing Confederate troops to abandon their artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, they paved the way for the Union to occupy the town of Jacksonville, Florida. The New York Times later recapped the events of the successful expedition as follows:

The expedition left Hilton Head on the afternoon of the 30th … consisting of the Pennsylvania Forty-seventh Regiment, Col. GOOD; the Connecticut Seventh Regiment, Col. HAWLEY; a section of the First Connecticut Battery, under Lieut. CARMON, and a detachment of the First Massachusetts Cavalry under Capt. CASE, making a total effective force of 1,573. The troops were embarked on the steamers Ben Deford, Boston, Cosmopolitan and Neptune, and arrived off the bar of the St. John’s River early on the morning following their departure, but were unable to enter the river until 2 P.M. in consequence of the shallowness of the channel. There the expedition was joined by the gunboats Paul Jones, Capt. STEEDMAN, commanding the fleet; Camerone, Capt. WOODHULL; Water Witch. Lieut. Com. PENDERGRAST; E.B. Hait, Lieut.-Com. SNELL; Uncas, Lieut.-Com. CRANE, and the Patroon, Lieut.-Com. URANO. The same afternoon three gunboats were sent up to feel, the position of the battery on the Bluff, and were immediately and warmly engaged, the enemy apparently having a number of heavy guns in his works.

The debarkation of our troops was effected at a place known as Mayport Mills, situated a short distance from the entrance of the river, and all the men, horses, rations and arms, were on shore by 9 o’clock on the evening of the 1st.

The country between this point and St. John’s Bluff presented great difficulties in the transportation of troops, being intersected with impassable swamps and unfordable creeks, and presenting an alternative of a march of forty miles without land transportation, to turn the head of the creek, or to reland up the river at a strongly-guarded position of the enemy. On further search, a landing place was found for the infantry at about 2 o’clock on the morning of the 2d, at a place called Buckhorn Creek, between Pable and Mount Pleasant Creeks, but the swampy [nature] of the ground made it impracticable to land the cavalry and artillery at that point. The gunboats here rendered valuable assistance by transporting troops and sending light howitzers in launches to cover the landing.

Col. GOOD, with the entire infantry and boat, howitzers, was ordered immediately forward to the head of Mount Pleasant Creek, to secure a position to cover the landing of the cavalry and artillery. The movement was executed skillfully, surprising and putting to fight the rebel pickets on that creek. This rapid movement to Mount Pleasant Creek, and the landing of the troops at Buck Horn Creek, was very fortunate, as it seemed to disarrange the enemy’s plan, if he had any, to prevent our disembarkation. Their pickets retired in such haste and trepidation as to leave their camps standing, their arms, and even a great portion of their clothing behind them, and only escaped themselves because of the intricate character of the ground and their superior knowledge of the country.

On the afternoon of the 3d, the artillery and cavalry were in readiness at the head of Mount Pleasant Creek, two miles from the enemy’s batteries at St. John’s bluff; and here the statement of persons belonging to the locality … appeared to agree in placing the strength of the rebels at 1,200 cavalry and infantry, in addition to the batteries, which they represented as containing nine heavy pieces. Under these circumstances; Gen. BRANNAN deemed it expedient, on consultation with Capt. STEEDMAN, to send the Cosmopolitan to Fernandina for reinforcements from the garrison of that place, and three hundred men, of the Ninth Maine Regiment, were sent down on the following morning.

Later in the day, at Gen. BRANNAN’s request, Capt. STEEDMAN sent three gunboats to feel the position of the enemy, shelling them as they advanced, when the batteries were found to be vacated, and Lieut. SNELL, of the Hale, sent a boat on shore and raised the American flag, finding the rebel flag in the battery. The naval force then retained possession, until the arrival of the troops, who immediately advanced from the position on Mount Pleasant Creek. On approaching the enemy’s position on the Bluff, it was found to be of great strength, possessing a heavy and effective armament, consisting of two eight-inch columbiads, two eight-inch siege howitzers, two eight-inch seacoast howitzers, and two rifled guns, supplied with ammunition in abundance, shot, shell, tools and camp equipage.

The works were skillfully and carefully constructed, and the strength of the position was greatly enhanced by the natural features of the ground, it being only approachable on the land side, through a winding ravine immediately under the guns of the position, and, from the narrowness of the river and the elevation of the bluff, rendering fighting by the gunboats most difficult and dangerous. Most of the guns were mounted on complete traverse circles, and, indeed, taking everything into consideration, there is no doubt that a small party of determined men might have maintained the position for a considerable time against even a larger force than we brought against it.

On the day following our occupation of these works the guns were dismounted and removed on board the steamer Neptune, together with the shot and shell, and removed to Hilton Head. The powder was all used in destroying the batteries.

As soon as we had got possession of the Bluff, Capt. STEEDMAN and his gunboats went to Jacksonville for the purpose of destroying all boats and intercepting the passage of the rebel troops across the river, and on the 5th Gen. BRANNAN also went up to Jacksonville in the steamer Ben Deford, with a force of 785 infantry, and occupied the town. On either side of the river were considerable crops of grain, which would have been destroyed or removed, but this was found impracticable for want of means of transportation. At Yellow Bluff we found that the rebels had a position in readiness to secure seven heavy guns, which they appeared to have lately evacuated, Jacksonville we found to be nearly deserted, there being only a few old men, women, and children in the town, soon after our arrival, however, while establishing our picket line, a few cavalry appeared on the outskirts, but they quickly left again. The few inhabitants were in a wretched condition, almost destitute of food, and Gen. BRANNAN, at their request, brought a large number up to Hilton Head to save them from starvation, together with 276 negroes — men, women, and children, who had sought our protection.

On the 6th inst., hearing that some rebel steamers were secreted in the creeks up the river, the Darlington, with 100 men of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, under Capt. YARD, and two 24-pound light howitzers and twenty-five men, commanded by Lieut. WILLIAMS, United States Navy, under a convoy of gun boats, was sent up to cut them out. This party returned on the 9th, having penetrated the river a distance of 130 miles, and bringing with them the steamer Governor Milton, which they captured in a creek, about twenty-seven miles from the town of Enterprise.

Finding that the Cosmopolitan, which had been sent to Hilton Head for provisions, had struck heavily in crossing the bar, on her return to the St. John’s River, and was temporarily disabled for service, the Seventh Connecticut Regiment was sent to Hilton Head on the Boston, with the request that she should return for the remainder of the troops, and she got back on the 11th, when the command was reembarked, reaching this plane yesterday, excepting one company of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, which is left for the protection of the Cosmopolitan. The accident to this valuable steamer is severe. A large hole was made in her bottom and she filled, but she will not be a wreck, as was at first feared.

Gen. BRANNAN thinks it evident, from his experience on this expedition, that the rebel troops in this portion of the country have not sufficient organization and determination, in consequence of their living in separate and distinct companies, to sustain any position, but seem rather to devote themselves to a system of guerrilla warfare. This was exemplified by the advance on St. John’s Bluff, where, after evacuating the fort, they continued to hover on our flanks and front, but did not come near enough to make their fire effective. We learned at Jacksonville that they commenced evacuating the Bluff immediately after our surprise of their pickets at Mount Pleasant Creek.

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th Pennsylvania engaged heavily protected Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina, including at Frampton’s Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge. Losses were significant. Two officers and 18 enlisted men from the 47th died; two officers and another 114 enlisted were wounded. In his report to superiors, penned on 24 October 1862, Colonel Good described how the battle unfolded:

Eight companies, comprising 480 men, embarked on the steamship Ben De Ford, and two companies, of 120 men, on the Marblehead, at 2 p.m. October 21. With this force I arrived at Mackays Landing before daylight the following morning. At daylight I was ordered to disembark my regiment and move forward across the first causeway and take a position, and there await the arrival of the other forces. The two companies of my regiment on board of the Marblehead had not yet arrived, consequently I had but eight companies of my regiment with me at this juncture.

At 12 m. I was ordered to take the advance with four companies, one of the Forty-seventh and one of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania Volunteers, and two of the Sixth Connecticut, and to deploy two of them as skirmishers and move forward. After moving forward about 2 miles I discerned some 30 or 40 of the enemys [sic] cavalry ahead, but they fled as we advanced. About 2 miles farther on I discovered two pieces of artillery and some cavalry, occupying a position about three-quarters of a mile ahead in the road. I immediately called for a regiment, but seeing that the position was not a strong one I made a charge with the skirmishing line. The enemy, after firing a few rounds of shell, fled. I followed up as rapidly as possible to within about 1 mile of Frampton Creek. In front of this stream is a strip of woods about 500 yards wide, and in front of the woods a marsh of about 200 yards, with a small stream running through it parallel with the woods. A causeway also extends across the swamp, to the right of which the swamp is impassable. Here the enemy opened a terrible fire of shell from the rear, of the woods. I again called for a regiment, and my regiment came forward very promptly. I immediately deployed in line of battle and charged forward to the woods, three companies on the right and the other five on the left of the road. I moved forward in quick-time, and when within about 500 yards of the woods the enemy opened a galling fire of infantry from it. I ordered double-quick and raised a cheer, and with a grand yell the officers and men moved forward in splendid order and glorious determination, driving the enemy from this position.

On reaching the woods I halted and reorganized my line. The three companies on the right of the road (in consequence of not being able to get through the marsh) did not reach the woods, and were moved by Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander by the flank on the causeway. During this time a terrible fire of grape and canister was opened by the enemy through the woods, hence I did not wait for the three companies, but immediately charged with the five at hand directly through the woods; but in consequence of the denseness of the woods, which was a perfect matting of vines and brush, it was almost impossible to get through, but by dint of untiring assiduity the men worked their way through nobly. At this point I was called out of the woods by Lieutenant Bacon, aide-de-camp, who gave the order, ‘The general wants you to charge through the woods.’ I replied that I was then charging, and that the men were working their way through as fast as possible. Just then I saw the two companies of my regiment which embarked on the Marblehead coming up to one of the companies that was unable to get through the swamp on the right. I went out to meet them, hastening them forward, with a view of re-enforcing the five already engaged on the left of the road in the woods; but the latter having worked their way successfully through and driven the enemy from his position, I moved the two companies up the road through the woods until I came up with the advance. The two companies on the right side of the road, under Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander had also worked their way up through the woods and opened fire on the retreating enemy. At this point I halted and reorganized my regiment, by forming close column by companies.

I then detailed Lieutenant Minnich, of Company B, and Lieutenant Breneman, of Company H, with a squad of men, to collect the killed and wounded. They promptly and faithfully attended to this important duty, deserving much praise for the efficiency and coolness they displayed during the fight and in the discharge of this humane and worthy trust.

The casualties in this engagement were 96. Captain Junker of Company K; Captain Mickley, of Company I, and Lieutenant Geety, of Company H, fell mortally wounded while gallantly leading their respective companies on.

I cannot speak too highly of the conduct of both officers and men. They all performed deeds of valor, and rushed forward to duty and danger with a spirit and energy worthy of veterans.

The rear forces coming up passed my regiment and pursued the enemy. When I had my regiment again placed in order, and hearing the boom of cannon, I immediately followed up, and, upon reaching the scene of action, I was ordered to deploy my regiment on the right side of the wood, move forward along the edge of it, and relieve the Seventh Connecticut Regiment. This I promptly obeyed. The position here occupied by the enemy was on the opposite side of the Pocotaligo Creek, with a marsh on either side of it, and about 800 yards distant from the opposite wood, where the enemy had thrown up rifle pits all along its edge.

On my arrival the enemy had ceased firing; but after the lapse of a few minutes they commenced to cheer and hurrah for the Twenty-sixth South Carolina. We distinctly saw this regiment come up in double-quick and the men rapidly jumping into the pits. We immediately opened fire upon them with terrible effect, and saw their men thinning by scores. In return they opened a galling fire upon us. I ordered the men under cover and to keep up the fire. During this time our forces commenced to retire. I kept my position until all our forces were on the march, and then gave one volley and retired by flank in the road at double-quick about 1,000 yards in the rear of the Seventh Connecticut. This regiment was formed about 1,000 yards in the rear of my former position. We jointly formed the rear guard of our forces and alternately retired in the above manner.

My casualties here amounted to 15 men.

We arrived at Frampton (our first battle ground) at 8 p.m. Here my regiment was relieved from further rear-guard duty by the Fourth New Hampshire Regiment. This gave me the desired opportunity to carry my dead and wounded from the field and convey them back to the landing. I arrived at the above place at 3 o’clock the following morning.

The challenging environment of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad was illustrated by Harper’s Weekly in 1865.

Good then added the following information in a follow-up report the next day:

After meeting the enemy in his first position he was driven back by the skirmishing line, consisting of two companies of the Sixth Connecticut, one of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, and one of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania, under my command. Here the enemy only fired a few rounds of shot and shell. He then retreated and assumed another position, and immediately opened fire. Colonel Chatfield, then in command of the brigade, ordered the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania forward to me, with orders to charge. I immediately charged and drove the enemy from the second position. The Sixth Connecticut was deployed in my rear and left; the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania on my right, and the Fourth New Hampshire in the rear of the Fifty-fifth, both in close column by divisions, all under a heavy fire of shell and canister. These regiments then crossed the causeway by the flank and moved close up to the woods. Here they were halted, with orders to support the artillery. After the enemy had ceased firing the Fourth New Hampshire was ordered to move up the road in the rear of the artillery and two companies of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania to follow this regiment. The Sixth Connecticut followed up, and the Fifty-fifth moved up through the woods. At this juncture Colonel Chatfield fell, seriously wounded, and Lieutenant-Colonel Speidel was also wounded.

The casualties in the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania amounted to 96 men. As yet I am unable to learn the loss of the entire brigade.

The enemy having fled, the Fourth New Hampshire and the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania followed in close pursuit. During this time the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania and the Sixth Connecticut halted and again organized, after which they followed. On coming up to the engagement I assumed command of the brigade, and found the forces arranged in the following order: The Fourth New Hampshire was deployed as skirmishers along the entire front, and the Fifty-fifth deployed in line of battle on the left side of the road, immediately in the rear of the Fourth New Hampshire. I then ordered the Sixth Connecticut to deploy in the rear of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania and the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania to deploy on the right side of the road in line of battle and relieve the Seventh Connecticut. I then ordered the Fourth New Hampshire, which had spent all its ammunition, back under cover on the road in the woods. The enemy meantime kept up a terrific fire of grape and musketry, to which we replied with terrible effect. At this point the orders were given to retire, and the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania and Seventh Connecticut formed the rear guard. I then ordered the Thirty-seventh Pennsylvania to keep its position and the Sixth Connecticut to march by the flank into the road and to the rear, the Fourth New Hampshire and Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania to follow. The troops of the Second Brigade were meanwhile retiring. After the whole column was in motion and a line of battle established by the Seventh Connecticut about 1,000 yards in the rear of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania I ordered the Forty-seventh to retire by the flank and establish a line of battle 1,000 yards in the rear of the Seventh Connecticut; after which the Seventh Connecticut moved by the flank to the rear and established a line of battle 1,000 yards in the rear of the Forty seventh, and thus retiring, alternately establishing lines, until we reached Frampton Creek, where we were relieved from this duty by the Fourth New Hampshire. We arrived at the landing at 3 o’clock on the morning of the 23d instant.

The casualties of the Sixth Connecticut are 34 in killed and wounded and the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania 112 in killed and wounded. As to the remaining regiments I have as yet received no report.

The most seriously wounded members of the regiment were transported to the Union Army’s General Hospital on Hilton Head Island. By mid-November, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who were well enough to travel were shipped back to Key West for further garrison duty in Florida.

1863 – Early 1864

Dividing the 47th Pennsylvania up between forts in Key West and the Dry Tortugas in late 1862 and early 1863, Captain Graeffe and the men of A Company found themselves on duty again at Fort Taylor. As 1863 wound down, they learned that 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would also be sent north to Fort Myers, which had been abandoned in 1858 after the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. (General D. P. Woodbury, commander of the U.S. Army’s Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, had ordered that this outpost be resurrected in 1864 to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade and provide food and shelter for those fleeing Confederate forces—escaped slaves, Confederate Army deserters and pro-Union residents.) According to Schmidt:

Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard. Lt. Harris was directed to tow the Matchless if necessary.

Punta Rassa was probably the location where the troops disembarked, and was located on the tip of the southwest delta of the Caloosahatchee River … near what is now the mainland or eastern end of the Sanibel Causeway… Fort Myers was established further up the Caloosahatchee at a location less vulnerable to storms and hurricanes. In 1864, the Army built a long wharf and a barracks 100 feet long and 50 feet wide at Punta Rassa, and used it as an embarkation point for shipping north as many as 4400 Florida cattle….

Capt. Graeffe and company were disembarked on the evening of January 7, and Gen. Woodbury ordered the company to occupy Fort Myers on the south side of the Caloosahatchee, about 12 miles from its mouth and 150 miles from Key West. Shortly after, [a detachment of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company stationed on Useppa Island] was also ordered to proceed to Fort Myers and join the main body of Company A, the entire command under direct orders of the General who was in the area…. Gen. Woodbury returned to Key West on the Honduras prior to January 19, and the command was left in charge of Capt. Graeffe who dispatched various patrols in search of refugees for enlistment and for activities involving Confederate cattle shipments.

Company A’s muster roll provides the following account of the expedition under command of Capt. Graeffe: ‘The company left Key West Fla Jany 4. 64 enroute to Fort Meyers Coloosahatche River [sic] Fla. were joined by a detachment of the U.S. 2nd Fla Rangers at Punta Rossa Fla took possession of Fort Myers Jan 10. Captured a Rebel Indian Agent and two other men.’

A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documented the time of Graeffe and the men under his Florida command:

A small contingent of 20 men and two officers from the Pennsylvania 47th Regiment, led by Captain Henry Crain of the 2nd Regiment of Florida, arrived at [Fort Myers] on January 7, 1864. A short time later, the party was joined by another small detachment of the 47th under the command of Captain Richard A. Graeffe. Over a short period, increasing reinforcements of the fort led to increasing cattle raids throughout the region. A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.

Early on, according to Schmidt, Captain Graeffe sent the following report to Woodbury:

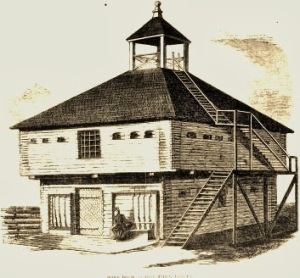

“At my arrival hier [sic] I divided my forces in three detachment, viz one at the Hospital one into the old guardhouse and one into the Comissary [sic] building, the Florida Rangers I quartered into one of the old Company quarters, I set all parties to work after placing the proper pickets and guards at the Hospital i have build [sic] and now nearly finished a two story loghouse of hewn and square logs 12 inches through seventeen by twenty-two fifteen feet high with a cupola onto the roof of six feet high and at right angle with two lines of picket fences seven feet high. i shall throw up a half a bastion around it as soon as completed. around the old guardhouse i have thrown up a bastion seven feet through at the foot and three feet on the top nine feet high from the bottom of the ditch and five on the inside. I also build [sic] a loghouse sixteen by eighteen of two storys [sic] Southeast of the Commissary building with a bastion around it at right angles with a picket fence each bastion has the distance you recomandet [sic] from the loghouses 20 feet on the sides and 20 to the salient angle, i caused to be dug a well close to bl. houses and inside of the bastions at each Station inside they are all comfortable fitted up with stationary bunks for the men without interfering with the defence [sic] of the work outside of the Bastions and inside the picket fense i have erected small kitchens and messrooms for each station, i am building now a guardhouse build [sic] of square hewn logs sixteen by sixteen two storys high the lower room to be used for the guard and the upper one as a prison, the building to be used for defence [sic] (in case of attack) by the Rangers each work is within view and supporting distance from the other; Capt. Crane with a detachment of his men repaired the wharf, which is in good condition now and fit for use, the bakehouse i got repaired, and the fourth day hier [sic] we had already very good fresh bread; the parade ground is in a good condition had all the weeds mowed off being to [sic] green to burn. i intend to fit up a schoolroom and church as soon as possible.”

Muster rolls for Company A from this period noted that “a detachment of 25 men crossed over to the north west side of the river” on 16 January and “scoured the country till up to Fort Thompson a distance of 50 miles,” where they “encountered a Rebel Picket who retreated after exchanging shots.” Making their way back, they swam across the river, and reached the fort on 23 January. Meanwhile, while that group was still away, Captain Graeffe ordered a smaller detachment of eight men to head out on 17 January in search of cattle. Finding only a few, they instead took possession of four barrels of Confederate turpentine, which were later disposed of by other Union troops.

Graeffe’s men also captured three Confederate sympathizers at the fort, including a blockade runner and spy named Griffin and an Indian interpreter and agent named Lewis. Charged with multiple offenses against the United States, they were transported to Key West, where they were kept under guard by the Provost Marshal—Major William Gausler, third-in-command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

This phase of duty lasted until sometime in February of 1864. The detachment of the 47th which served under Graeffe at Fort Myers is labeled as the Florida Rangers in several publications, including The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, prepared by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert N. Scott, et. al. (1891). Several of Graeffe’s hand drawn sketches of Fort Myers were published in 2000 in Images of America: Fort Myers by Gregg Tuner and Stan Mulford.

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had already left on the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reconstituted regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.

But they had missed the two bloodiest combat engagements that the 47th Pennsylvania would endure during the Red River Campaign—the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield on 8 April and the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April. According to Schmidt, Company A was soon ordered to return the Confederate prisoners to New Orleans, and officially ended their detached duty on 27 April when they rejoined the main regiment’s encampment at Alexandria.

This means that the men from Company A also missed a third combat engagement—the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry”), which took place on 23 April.

From late April through mid-May 1864, the fully reassembled 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and their fellow brigade members helped to build “Bailey’s Dam” near Alexandria, enabling federal gunboats to successfully navigate the fluctuating water levels of the Red River. Beginning 13 May, the regiment moved to Morganza, and then to New Orleans on 20 June before returning to Washington, D.C. aboard the McClellan from 5-12 July. Along the way, disease claimed still more men.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Still able and willing to fight, the soldiers of Company A and their fellow members of the 47th Pennsylvania were shipped north. Attached to the Army of the Shenandoah (Middle Military Division) from August through November of 1864, they were about to engage in the regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in the Battle of Berryville, and engaged in related post-battle skirmishes with the enemy over subsequent days. Joining with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Philip Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company A and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon”). The battle, also known as “Third Winchester,” is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and their supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. Finally reaching the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with the Confederate forces commanded by Early. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Rebel artillery stationed on high ground. Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and their fellow 19th Corps members were directed by Brigadier-General Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but many Union casualties ensued when another Confederate artillery group opened fire as Union troops tried to cross a clearing.

As a nearly fatal gap began to appear between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units commanded by Brigadier-Generals David A. Russell and Emory Upton. Russell, hit twice—once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers opened their lines long enough to enable Union cavalry forces led by William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank. The 19th Corps, with the 47th in the thick of the fighting, then began whittling away and pushing the Confederates steadily back. Early’s men ultimately retreated in the face of the valor displayed by the “blue jackets.” Leaving 2,500 wounded behind, the Confederate Army retreated to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September), eight miles south of Winchester, and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union men which outnumbered Early’s three to one.

Sent out on skirmishing parties afterward, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania finally made camp at Cedar Creek. Moving forward, they would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but they would do so without two respected commanders: Colonel Tilghman Good and his second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, who mustered out on 23-24 September upon expiration of their respective terms of service.

Battle of Cedar Creek — 19 October 1864

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

It was during 1864 that Major-General Philip Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s crop-production infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents—civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops—weakened by hunger—peeled off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally and win the day.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October 1864, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles—all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to historian, Samuel P. Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he rode rapidly past them – ‘Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’

The Union’s counterattack stomped Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions thusly:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went ‘whirling up the valley’ in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn, and no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

But once again, the casualties for the 47th were high. Privates Samuel E. Breidinger (a blacksmith from Easton), Thomas J. Bower (an Easton shoemaker) and Lawrence Gatence were killed in action. Private William S. Keen, a recent enlistee, died from his wounds a few weeks later.

Stationed at Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December, the 47th Pennsylvania was ordered to outpost duty at Camp Fairview in Charleston, West Virginia five days before Christmas.

1865

With those epic experiences behind him and a wife repeatedly writing letters which expressed hope that he would return home safe, sound—and soon, Private Stephen J. Moyer decided that he had had enough adventure in life, and availed himself of the opportunity to officially muster out from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. He was able to do so in early 1865 because he had, by that time, successfully completed the obligations of his original three-year term of enlistment.

So, on 17 January 1865, Private Stephen J. Moyer was honorably discharged at Stevenson, Virginia and, once again, became Mr. Stephen J. Moyer of Scranton, Pennsylvania.

Return to Civilian Life

Following his return to Pennsylvania, Stephen J. Moyer and his wife and children relocated to Tunkhannock in Wyoming County, where Stephen took up farming. That same year, their son Charles A. Moyer (1865-1942) became an early Christmas present, opening his eyes for the first time at the Moyer family home in Tunkhannock on 12 December 1865.

Their daughter, Elizabeth M. Moyer, arrived a year later in 1866, and was known as “Lizzie.” She was followed by two more daughters, Sadie Jane (1868-1959), who was born on 8 February 1868 and shown on the 1880 U.S. Census as “Sarah,” and Susie L., who was born on 27 May 1869.

Still farming in Tunkhannock in 1870, according to the U.S. Census, the Moyers continued to expand their family with the arrival of son William H. (1870-1936) on 26 January 1870, followed by son John P. Moyer (1872-1932), who was born on 7 May 1872, and daughter Anna (1873-1937), who was born on 7 June 1873 and known as “Annie.” Their son Edward S. Moyer (1874-1891), who was known by family members as “Eddie,” arrived on 16 August 1874.

Rail mills, Lackawanna Iron and Coal Company, circa 1878 (Hitchcock, Frederick L., et. al., History of Scranton and Its People, vol. 1, 1914, public domain).

In 1876, the Moyers celebrated two landmark events—the marriage of their son Charles to Carrie M. Snyder (1870-1960) on 26 January of that year—and the addition of another little one to their own family—daughter Bessie V. Moyer (1876-1885), who was born on 26 August 1876 in Scranton, the community to which the Moyers had returned in order for Stephen Moyer to resume employment with the railroad industry.