Born in Pennsylvania in July 1834, James Crownover was a son of Peter Crownover (1813-1869), a native of the Blacklog Valley in Pennsylvania’s Huntingdon County, and his first wife, Eleanor (Carmon) Crownover (1818-1848), a daughter of James Livingston Carmon and Martha (Johnston) Carmon.

James’ mother passed away in May 1848 when he was just 14 years old. His brother, Lloyd, then also died just over a month later. Both were laid to rest at the Barkley Cemetery in Aughwick, Huntingdon County.

In addition to brother Lloyd, James Crownover’s world was populated by Pennsylvania-born siblings: Martha, who was born sometime around 1841, later took the married surname of “Hamerick” and resided as a widow in 1880 in Rochelle, Ogle County, Illinois; Franklin Livingston (1842-1905), who served during the Civil War with Company H, 119th Illinois Infantry (1862-1865), wed sometime around 1871 and relocated to Nebraska with Mary Darr (circa 1851-1920), and became a farmer before passing away in Benedict, York County; and Marietta Crownover (1845-1918), who also relocated to York County, Nebraska, where she passed away on 22 December 1918.

Formative Years

Sometime following the death of James Crownover’s mother, Crownover family patriarch Peter remarried, taking as his bride, Mary Catherine Frankenberry (1828-1874), a native of Maryland and daughter of Samuel and Prussia (McDade) Frankenberry.

Additional Crownover children (James’ half-siblings) soon followed. Those born in Pennsylvania included: Laura, who was born sometime around 1854, later wed Samuel Work and raised a family with him in Rushville, Schuyler County, Illinois; Anne Grace, who was born 31 January 1853 and later wed Lee Martin; Amanda and Rebecca, who were respectively born sometime around 1854 and 1855. Son Elmer (1859-1938) is believed by Crownover family genealogists to have arrived after Peter Crownover had relocated his second wife and part of the Crownover brood to Missouri although another daughter Ida was reported to have been born in Pennsylvania sometime around 1862. Butler Benjamin and Lillian (1865-1937) were then born in McDonough County, Illinois, respectively, in 1865 and 1869.

1860s

By the dawn of America’s Civil War, James Crownover had grown up to become a 23-year-old teamster and resident of Blain in Perry County, Pennsylvania.

According to historian Harry Harrison Hain, the community of Blain was “nestle[d] in the famous Sherman’s Valley, near the western end of the county, the center of a veritable garden spot,” and “had its beginning in the early settlement which grew up about the mill erected by James Blaine in 1778, after whom the town took its name.”

Like Duncannon to the east and its other sister communities across Perry County, Blain became increasingly less rural as the 19th century waxed and waned. The image above right (taken from Hain’s book) illustrates the changes wrought over the years as explosives transformed local hillsides, enabling the Pennsylvania railroad system to expand and industry to move westward.

Civil War Military Service

At the age of 23, James Crownover became an early responder to calls by his Governor and President for help in defending America’s union. After enrolling for military service at Bloomfield in Perry County, Pennsylvania on 20 August 1861, he then mustered in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County on 31 August as a Private with Company D of the newly formed 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Military records at the time described him as being 5’8″ tall with dark eyes and black hair.

* Note: The Pennsylvania Veteran’s Burial Index Card for James Crownover lists his service company as “C,” but the rosters of Samuel P. Bates in History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5 noted that his affiliation was with “D” Company. Additionally, while his entry in the Pennsylvania Civil War Veterans’ Card File showed enrollment and muster-in dates of 2 and 11 September 1861, respectively, muster rolls for the 47th Pennsylvania documented his respective enrollment and muster dates as 20 and 31 August 1861.

Company D was led byHenry Durant Woodruff, a native of Waterbury, Connecticut who had been reared and educated in Windsor, New York until the age of 18 when he relocated to Perry County, Pennsylvania. A citizen member of the local militia in Bloomfield and, professionally, a teacher and then innkeeper until 1861, Henry Woodruff had not only performed his own Three Month’s Service in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for 75,000 volunteer troops to defend the nation’s capital following the fall of Fort Sumter in mid-April 1861, but had actually raised the unit he commanded—Company D of the 2nd Pennsylvania Infantry, comprised of residents from Bloomfield and other parts of Perry County. Commissioned a Captain with the 2nd Pennsylvania on 20 April 1861, he and his men served under General Robert Patterson at Winchester, Virginia. After completing his service, H. D. Woodruff mustered out at Camp Curtin on 26 July 1861, and then promptly raised a second company for a three-year term of service. Recruiting men from Bloomfield again, he re-enrolled on 20 August 1861, and was again commissioned as Captain, mustering in at Camp Curtin on 31 August. His unit became Company D of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, which had just been established weeks earlier by Tilghman H. Good.

Following a brief light infantry training period, Private James Crownover and his company were then sent by train with the 47th Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C. where, beginning 21 September, they were stationed at “Camp Kalorama” on Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, about two miles from the White House. Henry D. Wharton, a Musician with C Company, provided the following update on 22 September for readers of the Sunbury American, his hometown newspaper:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac River above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

As part of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Company D became part of the federal service when it officially mustered into the U.S. Army on 24 September. On 27 September, the 47th Pennsylvania was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania was on the move again. Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen marched behind their regimental band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (165 steps per minute using 33-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, Private James Crownover and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated close to the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (also known as “Baldy”) and were now part of the massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” for the large chestnut tree located within their lodging’s boundaries. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly 10 miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, Private James Crownover and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a letter home in mid-October, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin (the leader of C Company who would be promoted in 1864 to lead the entire 47th Regiment) reported that companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left-wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops.

In his own letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

The Unseen Foe

What may surprise readers most when studying the history of this and other Union regiments is that a fair number of “blue jackets” who lost their lives during the Civil War were claimed not by rifle or cannon fire, but by dysentery and other diseases commonly spread by troops suddenly placed in close military quarters, as well as by yellow fever and other tropical diseases which they encountered upon entering the Deep South.

As a result, the regiment lost its 13-year-old drummer boy and James Crownover’s Company D comrade, Sergeant Frank M. Holt, within weeks of their contracting Variola (smallpox). Both were initially then laid to rest in the cemetery adjacent to the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s National Home in Washington, D.C. that October of 1861.

On Friday morning, 22 October, Private Crownover and the remaining 47th Pennsylvanians then engaged in a Divisional Review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” Less than a month later, in his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review by overseen by the regiment’s founder, Colonel Tilghman H. Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward—and in preparation for even bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained brand new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

1862

U.S. Naval Academy Barracks and temporary hospital, Annapolis, Maryland, circa 1861-1865 (public domain).

Next ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were sent by rail to Alexandria, and then sailed the Potomac via the steamship City of Richmond to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped before they were marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C.

The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped aboard the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

On the afternoon of 27 January 1862, the 47th Pennsylvanians then commenced boarding the Oriental. Ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamers, the officers boarded last and, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, the Oriental steamed away at 4 p.m. Private James Crownover and his fellow soldiers were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

They arrived in Key West by early February of 1862. There, they were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor and drilled daily in heavy artillery tactics and other military strategies. During the weekend of Friday, 14 February, the 47th Pennsylvanians introduced their presence to Key West residents as the regiment paraded through the streets of the city. That Sunday, a number of the men mingled with area residents as they attended services at a local church.

From mid-June through July, the 47th was ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina where the men made camp before being housed in the Department of the South’s Beaufort District. Picket duties north of the 3rd Brigade’s camp were commonly rotated among the regiments present there at the time, putting soldiers at risk from sniper fire and other hazards. According to historian Samuel P. Bates, the men of the 47th “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing.”

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

On 16 August 1862, while stationed with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers in the Lower Seaboard Theater, Private James Crownover was promoted to the rank of Corporal.

Saint John’s Bluff, Florida

Sent on a return expedition to Florida, Corporal James Crownover and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians saw their first truly intense moments when they participated with other Union regiments in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff, Florida from 1 to 3 October 1862. Led by Brigadier-General Brannan, a 1,500-plus Union force disembarked at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek from troop carriers guarded by Union gunboats. Taking point, the 47th led the 3rd Brigade through 25 miles of dense, pine forested swamps populated with deadly snakes and alligators. By the time the expedition ended, the brigade had forced the Confederate Army to abandon its artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, and had paved the way for the Union to occupy the town of Jacksonville, Florida.

Integration of the Regiment

On 5 and 15 October 1862, respectively, the military unit founded by Colonel Tilghman Good made history as the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry became an integrated regiment, adding to its muster rolls several young to middle-aged Black men who had been freed from enslavement on plantations in the vicinity of Beaufort, South Carolina:

- Just 16 years old at the time of his enlistment, Abraham Jassum joined the 47th Pennsylvania from a recruiting depot on 5 October 1862. Military records indicate that he mustered in as “negro undercook” with Company F at Beaufort, South Carolina. Military records described him as being 5 feet 6 inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, and stated that his occupation prior to enlistment was “Cook.” Records also indicate that he continued to serve with F Company until he mustered out at Charleston, South Carolina on 4 October 1865 when his three-year term of enlistment expired.

- Also signing up as an Under Cook that day at the Beaufort recruiting depot was 33-year-old Bristor Gethers. Although his muster roll entry and entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File in the Pennsylvania State Archives listed him as “Presto Gettes,” his U.S. Civil War Pension Index listing spelled his name as “Bristor Gethers” and his wife’s name as “Rachel Gethers.” This index also includes the aliases of “Presto Garris” and “Bristor Geddes.” He was described on military records as being 5 feet 5 inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, and as having been employed as a fireman. He mustered in as “Negro under cook” with Company F on 5 October 1862, and mustered out at Charleston, South Carolina on 4 October 1865 upon expiration of his three-year term of service. Federal records indicate that he and his wife applied for his Civil War Pension from South Carolina.

- Also attached initially to Company F upon his 15 October 1862 enrollment with the 47th Pennsylvania, 22-year-old Edward Jassum was assigned kitchen duties. Records indicate that he was officially mustered into military service at the rank of Under Cook with the 47th Pennsylvania at Morganza, Louisiana on 22 June 1864, and then transferred to Company H on 11 October 1864. Like Abraham Jassum, Edward Jassum also continued to serve with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers until being honorably discharged on 14 October 1865 upon expiration of his three-year term of service.

More men of color would continue to be added to the 47th Pennsylvania’s rosters in the weeks and years to come.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

The challenging environment of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad was illustrated by Harper’s Weekly in 1865.

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, Corporal James Crownover and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians engaged Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point, the men of the 47th were placed on point once again, but they and the 3rd Brigade were less fortunate this time.

Harried by snipers en route to the Pocotaligo Bridge, they met resistance from an entrenched, heavily fortified Confederate battery which opened fire on the Union troops as they entered an open cotton field. Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests.

The Union soldiers grappled with the Confederates where they found them, pursuing the Rebels for four miles as they retreated to the bridge. There, the 47th relieved the 7th Connecticut. But the enemy was just too well armed. After two hours of intense fighting in an attempt to take the ravine and bridge, depleted ammunition forced the 47th to withdraw to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th were significant. Two officers and 18 enlisted men died; two officers and another 114 enlisted were wounded, including Corporal James Crownover, who had been shot in the chest. He survived and, after receiving treatment, was ultimately able to return to service with his D Company comrades

On 23 October, the 47th Pennsylvania returned to Hilton Head, where it served as the funeral Honor Guard for Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South who had succumbed to yellow fever on 30 October. Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, was later named for him. Men from the 47th Pennsylvania were given the honor of firing the salute over his grave.

1863

Fort Jefferson, Dry Torguas, Florida (interior, circa 1934, C.E. Peterson, photographer, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

By 1863, Corporal James Crownover and the men of D Company were once again based with the 47th Pennsylvania in Florida. Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November of 1862, much of 1863 was spent guarding federal installations in Florida as part of the 10th Corps, Department of the South. Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I garrisoned Fort Taylor in Key West while Companies D, F, H, and K garrisoned Fort Jefferson in Florida’s Dry Tortugas.

The time spent here by the men of Company D and their fellow Union soldiers was notable also for the men’s commitment to preserving the Union. Many who could have returned home chose instead to re-enlist in order to finish the fight.

Corporal James Crownover was one of those men who re-upped for a second three-year term of service. As a reward for re-enlisting at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida on 10 October 1863, he earned the coveted designation of “Veteran Volunteer,” and was also promoted to the rank of Sergeant that same day.

A letter to the New York Times, reprinted in the 30 April 1864 edition of the Semi-Weekly Wisconsin in Milwaukee, provided insight into the mindsets of the men from company D:

Remarkable History of a Military Company

To the Editor of the New York Times:Company D of the 47th Pennsylvania Regiment, a portion of which recently spent some time at the Soldiers’ Rest, in our city, on the way to Key West, can show the following record. There are in the company the following men:

William Powell, } Four brothers and a cousin.

John Powell,

Andrew Powell,

Solomon Powell,

Daniel Powell,John Brady, } All brothers.

William Brady,

Ackinson Brady,

Leonard Brady,Jacob Baltzer [sic], } Brothers.

George Baltzer [sic],

Benjamin Baltzer [sic],George Krosier [sic], } Brothers.

William Krosier [sic],

Jesse Krosier [sic],Edward Harper, } Brothers [sic] and Brothers-in-law

Marvin Harper, of the Captain.

George Harper,Jesse Shaffer, } Two Brothers and a Cousin.

Benjamin Shaffer,

William Shaffer,Wilson Tag, } Father and two sons; father

James Tag, served in Mexican War.

Richard Tag,John Clay, } Six pairs of brothers.

George Clay,

Jacob Charles,

Eli Charles,

John Reynolds,

Jesse Reynolds,

John Vance,

Jonathan Vance,

John Anthony,

Benjamin Anthony,

William Vertig [sic],

Franklin Vertig [sic],Isaac Baldwin, } Step-brothers.

Cyrus Taylor,These men all hail from Perry county, Pennsylvania. They are mainly of the old Holland stock, and lived within a circuit of fifteen miles. They are all re-enlisted men but two or three.

The company has been out over two years, most of the time at the extreme southern points. During eighteen months they lost but one man by sickness. They kept up strict salary regulations, commuted their rations of salt meat for fresh meat and vegetables, and saved by the operation from one hundred to one hundred thirty dollars a month, with which they made a company fund, appointing the Captain treasurer, and out of which whatever knick-nacks [sic] were needed could be purchased.

They always ate at a table, which they fixed with cross sticks, and had their food served from large bowls, each man having his place, as at home, which no one else was allowed to occupy. While the men were here, they showed that they were sober, cheerful, intelligent men, who had put their hearts into their work, and did not count any privations or sacrifices too great, if only the life of the country might thereby be maintained. During the whole term of their service, they had not had a man court-martialed.

They are commanded by Captain Henry D. Woodruff, a native of Binghamton, in this State, but long a resident of Pennsylvania. Their First Lieutenant is S. Ouchmuty [sic]; Second Lieutenant, George Stroop.

If any company can show a more striking record, it would be very interesting to know it.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to expand the Union’s reach. Regimental leaders did so, first, by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858 following the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. Per orders issued earlier in 1864 by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, that the fort be used to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade, Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of men from Company A were charged with expanding the fort and conducting raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. Graeffe and his men subsequently turned the fort into both their base of operations and a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate Army deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops.

Then while that mission was unfolding, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry began preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reconstituted regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Red River Campaign

From 14-26 March, the 47th passed through New Iberia, Vermilionville, Opelousas, and Washington while en route to Alexandria and Natchitoches, Louisiana. Sadly, Private William Mays of Company D would be among those from the 47th who would not survive the Red River experience. One of the early casualties in this campaign, he died from disease-related complications at the Union’s General Hospital in New Orleans on 30 March 1864.

From 4-5 April 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania added to its roster of young Black soldiers when 18-year-old John Bullard enrolled for service with Company D at Natchitoches, and Aaron and James Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled with other companies of the 47th. According to his entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives, John Bullard was officially mustered in for duty on 22 June “as (Colored) Cook.”

Often short on food and water, the regiment encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, 60 members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads. The fighting waned only when darkness fell. Exhausted, those who were uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner and son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

Casualties were once again severe. Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander was nearly killed, and the regiment’s two color-bearers, both from Company C, were also wounded while preventing the American flag from falling into enemy hands. Private Ephraim Clouser of Company D was shot in his right knee, and Corporal Isaac Baldwin was also wounded.

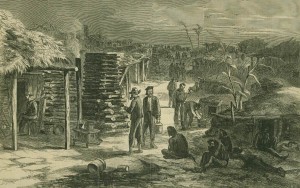

An illustration of the challenging life at Camp Ford, the largest Confederate Army prison camp west of the Mississippi River. (Harper’s Weekly, 4 March 1865, public domain).

Also wounded in the right shoulder while fighting in the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on 9 April 1864, Sergeant James Crownover was captured by Confederate forces, as were more than a dozen other men from the regiment. Marched and transported by train roughly 125 miles to Camp Ford (the Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas that was the largest CSA prison west of the Mississippi River), he was held as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange between the Union and Confederate armies on 25 November 1864.

* Note: During his captivity as a POW at Camp Ford in Texas, on 31 August 1864, Sergeant James Crownover was commissioned, but not mustered, as a Second Lieutenant. While one source states that he embarked on a 60-day furlough from a Union parole camp at Lake Ponchartrain near New Orleans, Louisiana after having been released via parole on 16 June 1864 at Red River Landing, multiple other sources—including Union Army muster rolls and Camp Ford prison records—confirm that he was advanced in rank (but not mustered at that rank) while being held as a POW, and that he was then released during the Union-Confederate POW exchange on 25 November 1864.

This procedure of promoting men while they were held in captivity as POWs was a common practice for the 47th Pennsylvania. This was done both to protect the incarcerated 47th Pennsylvanians since officers were generally treated somewhat better at CSA prison camps than Union enlisted men, but also because of historical precedent. The Dix-Hill Cartel of 1862 enabled both sides to free larger numbers of soldiers when exchanging enlisted men for officers. In the case of second lieutenants like James Crownover, the CSA would receive four privates in return when his prisoner exchange occurred (versus the two privates the CSA would have received had he remained a sergeant). As a result, the newly commissioned Crownover was more likely to receive better treatment from guards and prison medical personnel that would keep him healthy and alive until his prisoner exchange could be arranged. That thinking by leaders of the 47th Pennsylvania proved to be correct since Crownover survived the rigors of Camp Ford (unlike three other 47th Pennsylvanians); he ultimately returned to active duty following his November 1864 parole and subsequent furlough which enabled him to receive medical treatment and regain his physical and mental strength following the ordeal.

Meanwhile, after what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, Crownover’s comrades in the 47th Pennsylvania fell back to Grand Ecore, where they remained for a total of eleven days. After engaging in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications in a brutal climate, they moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April 1864, arriving in Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that night after marching 45 miles. En route, the Union forces were attacked again—this time in the rear, but they were able to quickly end the encounter and continue on.

They then took part in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry”)—a Union victory on 23 April, and moved on. After reaching Alexandria on 26 April, they were placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, and were assigned yet again to the hard labor of fortification work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that enabled Union gunboats to more easily make their way back down the Red River. After 17 days in Alexandria, the broke camp on 13 May, and headed south. Three days later, they were facing off against Confederates again—this time in the Battle of Mansura near Marksville on 16 May. Continuing on, the surviving members of the 47th marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again.

While encamped at Morganza, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania in Beaufort (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864. The regiment then moved on once again, and arrived in New Orleans in late June.

As they did during their tour through the Carolinas and Florida, the men of the 47th had battled the elements and disease, as well as the Confederate Army, in order to survive and continue to defend their nation. But the Red River Campaign’s most senior leader, Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks, would not. Removed from command amid the controversy regarding the Union Army’s successes and failures, he was placed on leave by President Abraham Lincoln. He later redeemed himself by spending much of his time in Washington, D.C. as a Reconstruction advocate for the people of Louisiana.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Still able and willing to fight after their time in Bayou country, Company D and their fellow members of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies A, C, E, F, H, and I steamed aboard the McClellan for the East Cost beginning 7 July 1864. Following their arrival and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln, they then joined Major-General David Hunter’s forces in the fighting at Snicker’s Gap and, once again, assisted in defending Washington, D.C., and also helped to drive Rebel troops from Maryland. Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah beginning in August, early and mid-September saw the departure of several 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who had served honorably, including Company D’s Captain Henry Woodruff, First Lieutenant Samuel Auchmuty, and Sergeants Henry Heikel and Alex Wilson. All mustered out 18 September 1864 upon expiration of their service terms. Those members of the 47th who remained on duty were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor in what one member of the 47th described as “our hardest engagement.”

But Second Lieutenant James Crownover had missed all of these engagements, as well as the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, because he was still languishing in Rebel hands as a POW at Camp Ford in Texas. Finally, on 25 November 1864, he was released, and returned to the Union Army.

1865 – 1866

Matthew Brady’s photograph of spectators massing for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, at the side of the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. (Library of Congress: Public domain.)

Assigned first to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah in February, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania moved, via Winchester and Kernstown, back to Washington, D.C. where, on 19 April, they were again responsible for helping to defend the nation’s capital – this time following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Encamped near Fort Stevens, they received new uniforms and were resupplied.

Letters home and later newspaper interviews with survivors of the 47th Pennsylvania indicate that at least one member of the regiment was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while others may have guarded the Lincoln assassination conspirators during the early days of their imprisonment and trial.

As part of Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, Sergeant James Crownover and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians also participated in the Union’s Grand Review on 23-24 May.

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives, public domain).

On their final southern tour, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered first to Savannah, Georgia, where they were stationed from 31 May to 4 June. Again in Dwight’s Division, this time they served with the 3rd Brigade, Department of the South. Relieving the 165th New York Volunteers in Charleston, South Carolina in July, they then quartered in the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury. Duties during both of these phases were largely provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related (rebuilding or repairing key infrastructure items that had been destroyed or damaged during the long war).

But once again, disease stalked the 47th. Many who did not survive were initially interred in Charleston’s Magnolia Cemetery.

The day after Independence Day, Sergeant James Crownover was promoted yet again—this time to the rank of First Sergeant, the final rank at which he would ever formally muster.

Beginning on Christmas day of 1865, he and his fellow D Company soldiers joined the majority of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers in honorably mustering out at Charleston, South Carolina, a process which continued through early January 1866.

Following a stormy voyage home, the weary, battle-hardened 47th Pennsylvanians disembarked in New York City, and were then transported to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader on 9 January 1866, they were officially given their discharge papers and allowed, finally, to return home to their loved ones.

Life After the War

After returning home, James Crownover obtained civilian employment and, in 1868, wed Perry County native, Malissa Frances Harman (1847-1917), daughter of John Harmon, a native of Germany, and Mary Vanhorne, a native of England. (An alternate spelling of her maiden surname was “Harman.”)

From 1870 to 1877, he was employed at the large tannery in Henry’s Valley, located roughly ten miles south of Blain, and living with Malissa in Jackson Township, Perry County, Pennsylvania, along with their three-year-old daughter, Ella (1868-1938), who had been born in May 1868 (and was shown on other federal census records as Frances E. or Ellen).

In October 1870, son Franklin was born, followed by daughter Anna (“Annie”) in March 1873, and son James Oscar in August 1875.

* Note: Established as a new township in November 1843, Jackson Township was bordered by Toboyne and Madison townships to the west and east in Perry County, respectively, as well as by Juniata and Cumberland counties to the north and south. Having been sold several times since its inception, the tannery where James Crownover was employed ceased its operations in 1877, forcing James to find another line of work.

During this decade, The New Bloomfield Times regularly reported on James Crownover’s civic engagement. On 27 March 1877, the newspaper reported that he had been appointed to serve on the Grand Jury for Jackson Township for the April term while the 26 February 1878 edition announced that he had been elected to the post of Constable in Blain Borough, Perry County.

But by 1880, the Crownover clan had relocated to East Huntingdon Township in Westmoreland County where James, the elder, supported his larger family through employment as a teamster.

By the turn of the century, the family had relocated yet again, this time to Ward 3 of Braddock in Allegheny County. Ella, Frank and James (now shown on the census as “Oscar”) all still resided at home, as did daughter, Anna (Crownover) Eberhart, and her son, Laird Eberhart. (Annie, who was living at her parents’ home without her husband, had married an Ohio native sometime in the early months of 1894. Their son, Laird, had been born in December of that same year.)

* Note: In March 1959, Laird made arrangements for a government issued soldier’s headstone to be placed on the grave of his grandfather, James Crownover.

In addition, Malissa’s widowed mother, Mary Harman, also lived with the Crownover clan in 1880.

By 1900, James Crownover had landed a job as a laborer at a local mill, while his children Ella, Frank and Oscar were employed, respectively, as a saleswoman, bridge builder and carbon setter.

Just three years later, James Crownover was gone. Having answered his final bugle call in Allegheny County on 18 July 1903, he was then honored at well-attended funeral services before being laid to rest in Section C, Lot 65, Grave 1 of the Monongahela Cemetery in Braddock Hills, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania.

Sadly, just over a year later, son Oscar passed away at the Crownover family home in Braddock, Pennsylvania, succumbing to complications from valvular heart disease on 25 July 1904. He was just 27 years old, and had suffered from the condition for two years, having developed it performing stressful and dangerous work as a structural steel engineer. Like his father before him, he was laid to rest at the Monongahela Cemetery in Braddock Hills.

His widow, Malissa, lived nearly another decade and a half without him until she passed away from chronic interstitial nephritis at home at 543 Corey Avenue in Braddock at 9 a.m. on 14 August 1917. She was interred next to James at the Monongahela Cemetery on 16 August. Her daughter, Ella Crownover of the same address, was the informant. The Marshall Brothers Funeral Home in Braddock handled her arrangements.

Daughter Ella also went on to live a long full life. She spent her final days as a resident of the Ladies G.A.R. (Grand Army of the Republic) House, and it was there that she passed away from pneumonia on 17 July 1938. Following funeral services by the W.L. Dowler Funeral Home of Braddock, she was laid to rest in the same cemetery (Monongahela) where her parents had been previously interred.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

2. Crownover Family Death Records, in Death Certificates. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

3. Crownover, James, in “Applications for Headstones for U.S. Military Veterans,” in Records of the Office of the U.S. Quartermaster General (Record Group Number 92). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

4. Crownover, James, in Camp Ford Prison Records. Tyler, Texas: The Smith County Historical Society, 1864.

5. Crownover, James, in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1865. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

6. Crownover, James, in Pennsylvania Veterans’ Burial Index Card File. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

7. Crownover Mentions, in New Bloomfield Times (Perry County, Pennsylvania), in Historic Newspapers Collection. U.S. Library of Congress. Washington, D.C.: 1840-1922.

8. Ellis, Franklin and Austin N. Hungerford, ed. History of That Part of the Susquehanna and Juniata Valleys, Embraced in the Counties of Mifflin, Juniata, Perry, Union and Snyder, in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, vol. I. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Everts, Peck & Richards, 1886.

9. “Exchange of Prisoners; The Cartel Agreed Upon by Gen. Dix for the United States, and Gen. Hill for the Rebels, The,” in “Supplementary Articles.” New York, New York: The New York Times, 6 October 1862.

10. Hain, Harry Harrison. History of Perry County, Pennsylvania. Including Descriptions of Indians and Pioneer Life from the Time of Earliest Settlement. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Hain-Moore Company, 1922.

11. Oscar Crownover (obituary). Pittsburgh: The Pittsburgh Press, 26 July 1904.

12. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

14 U.S. Census (1870, 1880, 1900). Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

15. U.S. Veterans’ Schedule (1890). Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.