Alternate Spellings of Surname: Koser, Kosier, Kozier, Krosier

Born in Perry County, Pennsylvania on 15 June 1836, George W. Kosier was a 24-year-old carpenter residing in New Bloomfield, Perry County, when South Carolina and other southern states began seceding from the Union. The son of John and Mary (Rice) Kosier, he was the older brother of Jesse and William S. Kosier, also both natives of Perry County.

Jesse and William S. Kosier were, respectively, a 19-year-old tanner and 23-year-old laborer residing in Bloomfield, Perry County in 1861.

Civil War Military Service

The eldest of the Kosier brothers, George W. Kosier, was an early responder to President Abraham Lincoln’s 15 April 1861 call for volunteers to help defend the nation’s capital following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces. He enrolled and officially mustered in for military service on 20 April 1861 at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County. Awarded the rank of Corporal, he served with Company D of the 2nd Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Transported to Cockeysville, Maryland with his regiment the next day, via the Northern Central Railway, and then to York, Pennsylvania, Corporal George W. Kosier and the 2nd Pennsylvania remained in York until 1 June 1861 when they moved to Chambersburg, Pennsylvania. There, they were attached to the 2nd Brigade (under Brigadier-General George Wynkoop), 2nd Division (under Major-General William High Keim), in the Union Army corps commanded by Major-General Robert Patterson.

Ordered to Hagerstown, Maryland on 16 June and then to Funkstown, the regiment remained in that vicinity until 23 June.

On 2 July, Corporal George Kosier and his fellow 2nd Pennsylvania Volunteers served in a support role during the Battle of Falling Waters, Virginia—an encounter that would also see the participation of soldiers from other regiments who would, like Kosier and the 2nd Pennsylvania’s Company D, later join the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. One such unit engaged at Falling Waters was Company F of the 11th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Excerpt from larger montage of Battle of Falling Waters images (Harper’s Weekly, 27 July 1861, public domain). “Council of War” depicts “Generals Williams, Cadwallader, Keim, Nagle, Wynkoop, and Colonels Thomas and Longnecker” strategizing on the eve of battle.

The Battle of Falling Waters, fought on 2 July 1861, was the first Civil War battle in the Shenandoah Valley. (A second battle with a different military configuration occurred there in 1863.) Also known as the Battle of Hainesville or Hoke’s Run, this first Battle of Falling Waters helped pave the way for the Confederate Army’s victory at Manassas (Bull Run) on 21 July, according to several historians. The vigorous Confederate effort, although unsuccessful, is believed to have been a factor in the tempering of Union General Robert Patterson’s combat assertiveness in later battles.

The next day, Corporal George Kosier and his fellow 2nd Pennsylvanians occupied Martinsburg, Virginia. On 15 July, they advanced on Bunker Hill, and then moved on to Charlestown on 17 July before reaching Harper’s Ferry on 23 July. Three days later, on 26 July 1861, Corporal George Kosier and his regiment mustered out.

Three Brothers Hope for Three-Year Terms

Following the honorable completion of his Three Months’ Service, Corporal George W. Kosier promptly re-upped for a three-year term of service, re-enrolling at Bloomfield in Perry County, Pennsylvania on 20 August 1861. Joining him were his younger brothers, Jesse and William S. Kosier.

The brothers Kosier all mustered in at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg on 31 August 1861. George entered as a 25-year-old First Sergeant while Jesse and William entered as 19 and 23-year-old privates. All three were now part of the newly formed 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, founded by Colonel Tilghman H. Good.

Following a brief training period in light infantry tactics, the Kosier brothers—now under the command of Captain Henry D. Woodruff—were sent by train with D Company and the rest of the 47th Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C. There, they were stationed about two miles from the White House—at “Camp Kalorama” on Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, beginning 21 September. The next day, Company C Musician Henry D. Wharton penned the following update for the Sunbury American newspaper:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

On 24 September 1861, the members of Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers officially mustered in with the U.S. Army. Three days later, on September 27, a rainy, drill-free day which permitted many of the men to read or write letters home, the 47th Pennsylvanians were assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens. By that afternoon, they were on the move again, headed for the Potomac River’s eastern side where, upon arriving at Camp Lyon in Maryland, they were ordered to march double-quick over a chain bridge and off toward Falls Church, Virginia.

Arriving at Camp Advance at dusk, the men pitched their tents in a deep ravine about two miles from the bridge they had just crossed, near a new federal military facility under construction (Fort Ethan Allen), which was also located near the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (nicknamed “Baldy”), the commander of the Union’s massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Armed with Mississippi rifles supplied by the Keystone State, their job was to help defend the nation’s capital.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads after having been ordered with the 3rd Brigade to Camp Griffin. In a letter home in mid-October, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin (the leader of C Company who would be promoted in 1864 to lead the entire 47th Regiment) reported that companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops.

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th engaged in a Divisional Review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review by Colonel Tilghman Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward for their performance that day—and in preparation for the even bigger events which were yet to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan ordered that new Springfield rifles be obtained for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

1862

Ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862, marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church. Sent by rail to Alexandria, they then sailed the Potomac via the steamship City of Richmond to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped before they were marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C. The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped aboard cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

According to Schmidt and letters home from members of the regiment, those preparations ceased on Monday, 27 January, at 10 a.m. when:

The regiment was formed and instructed by Lt. Col. Alexander ‘that we were about drumming out a member who had behaved himself unlike a soldier.’ …. The prisoner, Pvt. James C. Robinson of Company I, was a 36 year old miner from Allentown who had been ‘disgracefully discharged’ by order of the War Department. Pvt. Robinson was marched out with martial music playing and a guard of nine men, two men on each side and five behind him at charge bayonets. The music then struck up with ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the procession was marched up and down in front of the regiment, and Pvt. Robinson was marched out of the yard.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were transported to Florida aboard the steamship U.S. Oriental in January 1862 (public domain).

Reloading then resumed. By that afternoon, when the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers commenced boarding the Oriental, they were ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamers. The officers boarded last and, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, the Oriental steamed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. They were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

In early February 1862, Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Key West, where they were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor and drilled daily in heavy artillery tactics and other military strategies. On 14 February, the regiment made itself known to area residents via a parade through the city’s streets. That weekend, soldiers from the regiment mingled with residents at local church services.

Members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry also felled trees and helped to build new roads in a climate which was far more challenging than what they had experienced to date—and in an area where the water quality was frequently poor. As a result, disease was a constant companion—an unseen foe that claimed the lives of multiple members of the regiment during this phase of duty.

But there were lighter moments as well. According to a letter penned by Henry Wharton on 27 February 1862, the regiment commemorated the birthday of former U.S. President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation (first delivered in 1796), the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February. The festivities resumed two days later when the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards.” This was then followed by a concert by the Regimental Band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

Fort Walker, Hilton Head, South Carolina, circa 1861 (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, public domain).

From mid-June through July, the 47th was ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina where the men made camp before moving on to a new home, which was located roughly 35 miles away in the Department of the South’s Beaufort District. Picket duties north of the 3rd Brigade’s camp were commonly rotated among the regiments present there at the time, putting soldiers at increased risk from sniper fire.

According to historian Samuel P. Bates the men of the 47th “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing” during this phase of duty.

Around this same time, detachments from the regiment were assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

Sent on a return expedition to Florida, Company D saw its first truly intense moments when it participated with the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff from 1 to 3 October.

Led by Brigadier-General Brannan, a 1,500-plus Union force disembarked at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek from troop carriers guarded by Union gunboats.

J. H. Schell’s 1862 illustration of the earthworks surrounding the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff along the Saint John’s River in Florida (public domain).

Taking point, the 47th led the 3rd Brigade through 25 miles of dense, pine-forested swamps, dodging deadly snakes and alligators. By the time the expedition ended, the brigade had forced the Confederate Army to abandon its artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, and had paved the way for the Union to occupy the town of Jacksonville, Florida.

In his report on the matter, filed from Mount Pleasant Landing, Florida on 2 October 1862, Colonel Tilghman H. Good described the Union Army’s assault on Saint John’s Bluff:

In accordance with orders received I landed my regiment on the bank of Buckhorn Creek at 7 o’clock yesterday morning. After landing I moved forward in the direction of Parkers plantation, about 1 mile, being then within about 14 miles of said plantation. Here I halted to await the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut Regiment. I advanced two companies of skirmishers toward the house, with instructions to halt in case of meeting any of the enemy and report the fact to me. After they had advanced about three-quarters of a mile they halted and reported some of the enemy ahead. I immediately went forward to the line and saw some 5 or 6 mounted men about 700 or 800 yards ahead. I then ascended a tree, so that I might have a distinct view of the house and from this elevated position I distinctly saw one company of infantry close by the house, which I supposed to number about 30 or 40 men, and also some 60 or 70 mounted men. After waiting for the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut Volunteers until 10 o’clock, and it not appearing, I dispatched a squad of men back to the landing for a 6-pounder field howitzer which had been kindly offered to my service by Lieutenant Boutelle, of the Paul Jones. This howitzer had been stationed on a flat-boat to protect our landing. The party, however, did not arrive with the piece until 12 o’clock, in consequence of the difficulty of dragging it through the swamp. Being anxious to have as little delay as possible, I did not await the arrival of the howitzer, but at 11 a.m. moved forward, and as I advanced the enemy fled.

After reaching the house I awaited the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut and the howitzer. After they arrived I moved forward to the head of Mount Pleasant Creek to a bridge, at which place I arrived at 2 p.m. Here I found the bridge destroyed, but which I had repaired in a short time. I then crossed it and moved down on the south bank toward Mount Pleasant Landing. After moving about 1 mile down the bank of the creek my skirmishing companies came upon a camp, which evidently had been very hastily evacuated, from the fact that the occupants had left a table standing with a sumptuous meal already prepared for eating. On the center of the table was placed a fine, large meat pie still warm, from which one of the party had already served his plate. The skirmishers also saw 3 mounted men leave the place in hot haste. I also found a small quantity of commissary and quartermasters stores, with 23 tents, which, for want of transportation, I was obliged to destroy. After moving about a mile farther on I came across another camp, which also indicated the same sudden evacuation. In it I found the following articles … breech-loading carbines, 12 double-barreled shot-guns, 8 breech-loading Maynard rifles, 11 Enfield rifles, and 96 knapsacks. These articles I brought along by having the men carry them. There were, besides, a small quantity of commissary and quartermasters stores, including 16 tents, which, for the same reason as stated, I ordered to be destroyed. I then pushed forward to the landing, where I arrived at 7 p.m.

We drove the enemys [sic] skirmishers in small parties along the entire march. The march was a difficult one, in consequence of meeting so many swamps almost knee-deep.

On 3 October, Good filed his report from Saint John’s Bluff, Florida, now in Union hands:

At 9 o’clock last night Lieutenant Cannon reported to me that his command, consisting of one section of the First Connecticut Battery, was then coming up the creek on flat-boats with a view of landing. At 4 o’clock this morning a safe landing was effected and the command was ready to move. The order to move to Saint John’s Bluff reached me at 4 p.m. yesterday. In accordance with it I put the column in motion immediately and moved cautiously up the bank of the Saint John’s River, the skirmishing companies occasionally seeing small parties of the enemy’s cavalry retiring in our front as we advanced. When about 2 miles from the bluff the left wing of the skirmishing line came upon another camp of the enemy, which, however, in consequence of the lateness of the hour, I did not take time to examine, it being then already dark.

After my arrival at the bluff, it then being 7:30 o’clock, I dispatched Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander with two companies back to the last-named camp (which I found, from a number of papers left behind, to have been called Camp Hopkins and occupied by the Milton Artillery, of Florida) to reconnoiter and ascertain its condition. Upon his return he reported that from every appearance the skedaddling of the enemy was as sudden as in the other instances already mentioned, leaving their trunks and all the camp equipage behind; also a small store of commissary supplies, sugar, rice, half barrel of flour, one bag of salt, &c., including 60 tents which I have brought in this morning. The commissary stores were used by the troops of my command.

Integration of the Regiment

On 5 and 15 October 1862, respectively, the 47th Pennsylvania then made history as it became an integrated regiment, adding to its muster rolls several young to middle-aged Black men who had endured plantation enslavement in Beaufort, South Carolina. Among the men freed who subsequently opted to enroll as members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were Abraham and Edward Jassum (aged 16 and 22, respectively), and Bristor Gethers (aged 33), whose name was spelled as “Presto Gettes” on transcriptions of muster rolls made by historian Samuel P. Bates. More men of color would continue to be added to the 47th Pennsylvania’s rosters in the weeks and years to come.

Battle of Pocotaligo

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th Pennsylvanians engaged Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point, the men of the 47th were placed on point once again, but they and the 3rd Brigade were less fortunate this time.

Harried by snipers en route to the Pocotaligo Bridge, they met resistance from an entrenched, heavily fortified Confederate battery which opened fire on the Union troops as they entered an open cotton field. Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests.

The Union soldiers grappled with the Confederates where they found them, pursuing the Rebels for four miles as they retreated to the bridge. There, the 47th relieved the 7th Connecticut. After two hours of intense fighting in an attempt to take the ravine and bridge, depleted ammunition forced the 47th to withdraw to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th were significant. Two officers and 18 enlisted men died; two officers and another 114 enlisted were wounded. Several resting places for men from the 47th still remain unidentified, the information lost to sloppy Army and hospital records management or to the trauma-impaired memories of soldiers forced to hastily bury or leave behind the bodies of comrades upon receiving orders to retreat.

In his report on the engagement, made from headquarters at Beaufort, South Carolina on 24 October 1862, Colonel Good wrote:

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following report of the part taken by the Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers in the action of October 22:

Eight companies, comprising 480 men, embarked on the steamship Ben De Ford, and two companies, of 120 men, on the Marblehead, at 2 p.m. October 21. With this force I arrived at Mackays Landing before daylight the following morning. At daylight I was ordered to disembark my regiment and move forward across the first causeway and take a position, and there await the arrival of the other forces. The two companies of my regiment on board of the Marblehead had not yet arrived, consequently I had but eight companies of my regiment with me at this juncture.

At 12 m. I was ordered to take the advance with four companies, one of the Forty-seventh and one of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania Volunteers, and two of the Sixth Connecticut, and to deploy two of them as skirmishers and move forward. After moving forward about 2 miles I discerned some 30 or 40 of the enemys [sic] cavalry ahead, but they fled as we advanced. About 2 miles farther on I discovered two pieces of artillery and some cavalry, occupying a position about three-quarters of a mile ahead in the road. I immediately called for a regiment, but seeing that the position was not a strong one I made a charge with the skirmishing line. The enemy, after firing a few rounds of shell, fled. I followed up as rapidly as possible to within about 1 mile of Frampton Creek. In front of this stream is a strip of woods about 500 yards wide, and in front of the woods a marsh of about 200 yards, with a small stream running through it parallel with the woods. A causeway also extends across the swamp, to the right of which the swamp is impassable. Here the enemy opened a terrible fire of shell from the rear, of the woods. I again called for a regiment, and my regiment came forward very promptly. I immediately deployed in line of battle and charged forward to the woods, three companies on the right and the other five on the left of the road. I moved forward in quick-time, and when within about 500 yards of the woods the enemy opened a galling fire of infantry from it. I ordered double-quick and raised a cheer, and with a grand yell the officers and men moved forward in splendid order and glorious determination, driving the enemy from this position.

On reaching the woods I halted and reorganized my line. The three companies on the right of the road (in consequence of not being able to get through the marsh) did not reach the woods, and were moved by Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander by the flank on the causeway. During this time a terrible fire of grape and canister was opened by the enemy through the woods, hence I did not wait for the three companies, but immediately charged with the five at hand directly through the woods; but in consequence of the denseness of the woods, which was a perfect matting of vines and brush, it was almost impossible to get through, but by dint of untiring assiduity the men worked their way through nobly. At this point I was called out of the woods by Lieutenant Bacon, aide-de-camp, who gave the order, ‘The general wants you to charge through the woods.’ I replied that I was then charging, and that the men were working their way through as fast as possible. Just then I saw the two companies of my regiment which embarked on the Marblehead coming up to one of the companies that was unable to get through the swamp on the right. I went out to meet them, hastening them forward, with a view of re-enforcing the five already engaged on the left of the road in the woods; but the latter having worked their way successfully through and driven the enemy from his position, I moved the two companies up the road through the woods until I came up with the advance. The two companies on the right side of the road, under Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander had also worked their way up through the woods and opened fire on the retreating enemy. At this point I halted and reorganized my regiment, by forming close column by companies. I then detailed Lieutenant Minnich, of Company B, and Lieutenant Breneman, of Company H, with a squad of men, to collect the killed and wounded. They promptly and faithfully attended to this important duty, deserving much praise for the efficiency and coolness they displayed during the fight and in the discharge of this humane and worthy trust.

The casualties in this engagement were 96. Captain Junker of Company K; Captain Mickley, of Company I [sic], and Lieutenant Geety, of Company H, fell mortally wounded while gallantly leading their respective companies on.

I cannot speak too highly of the conduct of both officers and men. They all performed deeds of valor, and rushed forward to duty and danger with a spirit and energy worthy of veterans.

The rear forces coming up passed my regiment and pursued the enemy. When I had my regiment again placed in order, and hearing the boom of cannon, I immediately followed up, and, upon reaching the scene of action, I was ordered to deploy my regiment on the right side of the wood, move forward along the edge of it, and relieve the Seventh Connecticut Regiment. This I promptly obeyed. The position here occupied by the enemy was on the opposite side of the Pocotaligo Creek, with a marsh on either side of it, and about 800 yards distant from the opposite wood, where the enemy had thrown up rifle pits all along its edge.

On my arrival the enemy had ceased firing; but after the lapse of a few minutes they commenced to cheer and hurrah for the Twenty-sixth South Carolina. We distinctly saw this regiment come up in double-quick and the men rapidly jumping into the pits. We immediately opened fire upon them with terrible effect, and saw their men thinning by scores. In return they opened a galling fire upon us. I ordered the men under cover and to keep up the fire. During this time our forces commenced to retire. I kept my position until all our forces were on the march, and then gave one volley and retired by flank in the road at double-quick about 1,000 yards in the rear of the Seventh Connecticut. This regiment was formed about 1,000 yards in the rear of my former position. We jointly formed the rear guard of our forces and alternately retired in the above manner.

My casualties here amounted to 15 men.

We arrived at Frampton (our first battle ground) at 8 p.m. Here my regiment was relieved from further rear-guard duty by the Fourth New Hampshire Regiment. This gave me the desired opportunity to carry my dead and wounded from the field and convey them back to the landing. I arrived at the above place at 3 o’clock the following morning.

In a second report made from Beaufort on 25 October 1862, Colonel Good added the following details:

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following report of the part taken by the First Brigade in the battles of October 22:

After meeting the enemy in his first position he was driven back by the skirmishing line, consisting of two companies of the Sixth Connecticut, one of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, and one of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania, under my command. Here the enemy only fired a few rounds of shot and shell. He then retreated and assumed another position, and immediately opened fire. Colonel Chatfield, then in command of the brigade, ordered the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania forward to me, with orders to charge. I immediately charged and drove the enemy from the second position. The Sixth Connecticut was deployed in my rear and left; the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania on my right, and the Fourth New Hampshire in the rear of the Fifty-fifth, both in close column by divisions, all under a heavy fire of shell and canister. These regiments then crossed the causeway by the flank and moved close up to the woods. Here they were halted, with orders to support the artillery. After the enemy had ceased firing the Fourth New Hampshire was ordered to move up the road in the rear of the artillery and two companies of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania to follow this regiment. The Sixth Connecticut followed up, and the Fifty-fifth moved up through the woods. At this juncture Colonel Chatfield fell, seriously wounded, and Lieutenant-Colonel Speidel was also wounded.

The casualties in the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania amounted to 96 men. As yet I am unable to learn the loss of the entire brigade.

The enemy having fled, the Fourth New Hampshire and the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania followed in close pursuit. During this time the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania and the Sixth Connecticut halted and again organized, after which they followed. On coming up to the engagement I assumed command of the brigade, and found the forces arranged in the following order: The Fourth New Hampshire was deployed as skirmishers along the entire front, and the Fifty-fifth deployed in line of battle on the left side of the road, immediately in the rear of the Fourth New Hampshire. I then ordered the Sixth Connecticut to deploy in the rear of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania and the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania to deploy on the right side of the road in line of battle and relieve the Seventh Connecticut. I then ordered the Fourth New Hampshire, which had spent all its ammunition, back under cover on the road in the woods. The enemy meantime kept up a terrific fire of grape and musketry, to which we replied with terrible effect. At this point the orders were given to retire, and the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania and Seventh Connecticut formed the rear guard. I then ordered the Thirty-seventh Pennsylvania to keep its position and the Sixth Connecticut to march by the flank into the road and to the rear, the Fourth New Hampshire and Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania to follow. The troops of the Second Brigade were meanwhile retiring. After the whole column was in motion and a line of battle established by the Seventh Connecticut about 1,000 yards in the rear of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania I ordered the Forty-seventh to retire by the flank and establish a line of battle 1,000 yards in the rear of the Seventh Connecticut; after which the Seventh Connecticut moved by the flank to the rear and established a line of battle 1,000 yards in the rear of the Forty seventh, and thus retiring, alternately establishing lines, until we reached Frampton Creek, where we were relieved from this duty by the Fourth New Hampshire. We arrived at the landing at 3 o’clock on the morning of the 23d instant.

The casualties of the Sixth Connecticut are 34 in killed and wounded and the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania 112 in killed and wounded. As to the remaining regiments I have as yet received no report.

Following their return to Hilton Head, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers recuperated from their wounds and resumed their normal duties. In short order, several members of the 47th were called upon to serve as the funeral Honor Guard for Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, and given the high honor of firing the salute over this grave. (Commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South, Mitchel succumbed to yellow fever on 30 October 1862. The Mountains of Mitchel, a part of Mars’ South Pole discovered in 1846 by Mitchel as a University of Cincinnati astronomer, and Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, were both named after him.)

1863

Fort Jefferson’s moat and wall, circa 1934, Dry Tortugas, Florida (C.E. Peterson, Library of Congress, public domain).

Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, much of 1863 for the Kosier brothers and their fellow 47th Pennsylvanians was spent garrisoning federal installations in Florida as part of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps, Department of the South. Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I remained on duty at Key West’s Fort Taylor while the soldiers from Companies D, F, H, and K garrisoned Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the coast of Florida.

In a letter to the Sunbury American on 23 August 1863, Henry Wharton described Thanksgiving celebrations held by the regiment and residents of Key West and a yacht race the following Saturday at which participants had “an opportunity of tripping the ‘light, fantastic toe,’ to the fine music of the 47th Band, led by that excellent musician, Prof. Bush.”

The time spent in Florida was notable also for the men’s commitment to preserving the Union. The climate was harsh and unpleasant and, as before, disease was a constant companion and foe. Many of the 47th who could have returned home, having well and honorably completed their service, chose instead to re-enlist.

Sergeant George W. Kosier re-upped for a third term on 10 October 1863, re-enlisting at Fort Taylor, Key West, Florida. That same day, his brother, Private Jesse Kosier, also re-enlisted at Fort Taylor—for a second three-year term of service. Their brother, Private William S. Kosier, re-enlisted at Fort Taylor on 18 December 1863, also for a second term of service.

A letter to the New York Times, reprinted in the 30 April 1864 edition of the Semi-Weekly Wisconsin in Milwaukee, provided insight into the mindsets of the Kosiers and other men from company D:

Remarkable History of a Military Company

To the Editor of the New York Times:

Company D of the 47th Pennsylvania Regiment, a portion of which recently spent some time at the Soldiers’ Rest, in our city, on the way to Key West, can show the following record. There are in the company the following men:

…George Krosier [sic], } Brothers.

William Krosier [sic],

Jesse Krosier [sic]…These men all hail from Perry county, Pennsylvania. They are mainly of the old Holland stock, and lived within a circuit of fifteen miles. They are all re-enlisted men but two or three.

The company has been out over two years, most of the time at the extreme southern points. During eighteen months they lost but one man by sickness. They kept up strict salary regulations, commuted their rations of salt meat for fresh meat and vegetables, and saved by the operation from one hundred to one hundred thirty dollars a month, with which they made a company fund, appointing the Captain treasurer, and out of which whatever knick-nacks [sic] were needed could be purchased.

They always ate at a table, which they fixed with cross sticks, and had their food served from large bowls, each man having his place, as at home, which no one else was allowed to occupy. While the men were here, they showed that they were sober, cheerful, intelligent men, who had put their hearts into their work, and did not count any privations or sacrifices too great, if only the life of the country might thereby be maintained. During the whole term of their service, they had not had a man court-martialed….

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858 following the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. Per orders issued earlier in 1864 by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, that the fort be used to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade, Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of men from Company A were charged with expanding the fort and conducting raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. (Graeffe and his men subsequently turned the fort into both their base of operations and a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate Army deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops.)

U.S. Military and New Orleans, Opelousas & Great Western trains, Algiers railroad shop, Louisiana, circa 1865 (public domain).

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the Kosier brothers and their Company D comrades joined the men of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies B, C, I, and K on that journey. Headed for Algiers, Louisiana (which is situated across the river from New Orleans and is now a neighborhood in New Orleans), they were followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reunited regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana) before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.)

Red River Campaign

Natchitoches, Louisiana (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 7 May 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click image to enlarge).

From 14-26 March, the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched for Alexandria and Natchitoches, Louisiana, by way of New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington.

From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James and John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were then officially mustered in for duty on 22 June at Morganza. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “(Colored) Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long, grueling trek through enemy territory, the 47th Pennsylvanians encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill on the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the 2nd Division, 60 members of the 47th were cut down on 8 April during the volley of fire unleashed by both sides during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield because of its proximity to the community of Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. Exhausted, those who were uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to the community of Pleasant Hill (now the Village of Pleasant Hill).

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, as the 47th was shifting to the left of the Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander, the regiment’s second-in-command, was nearly killed, and the regiment’s two color-bearers, both from Company C, were also wounded while preventing the regimental flag from falling into enemy hands.

Among the D Company men who were wounded that day were Private Ephraim Clouser, who was shot in his right knee, and Corporal Isaac Baldwin. Still others from the 47th were captured and held as prisoners of war until released during a a series of prisoner exchanges. Private James Downs, Corporal John Garber Miller, Private William J. Smith, and Sergeant James Crownover were four of “the fortunate ones.” Downs, Miller and Smith were released on 22 July 1864 while Crownover, who, despite his having been wounded in the right shoulder during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, was held far longer. (Viewed by his Confederate captors as more of “a bargaining chip” because of his higher rank, Crownover was commissioned, but not mustered, as a Second Lieutenant on 31 August 1864 by his superior officers, who hoped to inspire the Confederate troops who were holding him captive to treat him with care. Ultimately, he would not be released until 25 November 1864.)

Following what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, the 47th Pennsylvanians fell back to Grand Ecore, where they remained for 11 days and engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications. They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April, arriving in Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night, after marching 45 miles. While en route, they were attacked again—this time at the rear of their brigade, but they were able to quickly end the encounter and move forward.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April 1864), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee’s Confederate Cavalry in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”). Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s 20-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops situated near a bayou and on a bluff, Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending the other two brigades to find a safe spot where his Union troops could ford the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

As Emory’s troops worked their way toward the Cane River, they attacked Bee’s flank, forced a Rebel retreat, and erected a series of pontoon bridges, enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and other remaining Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners.

In a letter penned from Morganza, Louisiana on 29 May, Henry Wharton described what had happened to the 47th Pennsylvanians during and immediately after making camp at Grand Ecore:

Our sojourn at Grand Ecore was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one on the boys, for by ten o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty-five miles. On that day the rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns, opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebel prisoners say it ‘seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth of this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton of Western Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” for Lt.-Col. Joseph Bailey, the officer overseeing its construction, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, the 47th Pennsylvanians learned they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned yet again to the hard labor of fortification work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that enabled Union gunboats to more easily make their way back down the Red River. While stationed in Rapides Parish in late April and early May, according to Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam [Bailey’s Dam] had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits [sic] on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

On Sunday, May 15, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad wherewith the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired and we advanced ‘till dark, when the forces halted for the night, with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

Having entered Avoyelles Parish, the 47th Pennsylvanians “rested on their arms” for the night, half-dozing without pitching their tents, but with their rifles right beside them. They were now positioned just outside of Marksville, Louisiana on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, the infantry advanced in line until they reached Mousoula [sic], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic] on the Achafalaya [sic] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of our army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As Wharton noted, the surviving members of the 47th marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. While encamped there, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania in Beaufort (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (April 1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 20-24 June 1864.

The regiment then moved on once again, finally arriving back in New Orleans in late June. On the Fourth of July, the Kosier brothers and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers received orders to return to the East Coast. The members of the regiment were loaded onto ships in two stages: Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I steamed for the Washington, D.C. area aboard the McClellan, beginning 7 July, while the men from Companies B, G and K remained behind on detached duty and to await transportation. (Led by F Company Captain Henry S. Harte, the 47th Pennsylvanians who had been left behind in Louisiana finally sailed away at the end of the month aboard the Blackstone. Arriving in Virginia on 28 July, they reconnected with the bulk of the regiment at Monocacy, Virginia on 2 August.)

Although the Kosier brothers and the other members of D Company arrived in the Washington, D.C. area with the men from Companies A, C, E, F, H, and I as the Battle of Fort Stevens (11-12 July 1864) was under way, they appear not to have been engaged in the actual fighting.

They did, however, have a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln.

Attached now to the U.S. Army’s 19th Corps, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry who had reached the Washington, D.C. area by this time were quickly put to work soon afterward, which led to their rapid re-engagement in combat—at Snicker’s Gap, Virginia (17-19 July).

Also known as the Battle of Cool Spring, the Union Army went after the Confederate troops of Lieutenant-General Jubal Early as they retreated from their loss at Fort Stevens. Although Union forces commanded by other leaders lost their engagements, the Union troops led by Major-General David Hunter were able pry loose the hold Confederates had on Berryville, Virginia, a success which helped pave the way for Union Major-General Philip H. (“Little Phil”) Sheridan’s tide-turning 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

On 24 July, C Company Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin was promoted to the central regimental command staff at the rank of Major. Meanwhile, the Red River Campaign’s most senior leader, Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks, was being removed from command amid the debate regarding the Union Army’s successes and failures. Placed on leave by President Abraham Lincoln, he later redeemed himself by spending much of his time in Washington, D.C. as a Reconstruction advocate for the people of Louisiana.

An Old Foe Returns and Fells a Family Member

Barely a month after returning to the East Coast, tragedy struck the Kosier family when, on 30 August 1864, Private Jesse Kosier died from pleurisy at the Union Army’s Field Hospital in Sandy Hook, Maryland. His death was certified by N. F. Graham, Assistant Staff Surgeon.

Note: Some sources indicate that Jesse Kosier’s date of death occurred on 31 October 1864 in Weverton, Maryland or at Antietam; however, these dates and locations are incorrect. The federal burial ledger for Jesse Kosier, shows that he died from pleurisy on 30 August at the “F.H. Sandy Hook Md.” The entry’s handwriting is unclear, and the physician may have spelled Jesse’s surname incorrectly as “Kaseir” rather than “Kosier,” but the regiment and rank are a match (source: Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, U.S. Office of the Adjutant General, Record Group 94, U.S. National Archives).

This entry in the Union Army’s death ledger for volunteer soldiers confirms that Private Jesse Kosier, Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, died from pleurisy at the Union Field Hospital at Sandy Hook, Maryland on 30 August 1864. (Click once or twice to enlarge.)

Additionally, although Jesse Kosier’s entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives indicates that he was interred at “Antietam,” an entry on the federal burial ledger for the Antietam National Battlefield site shows that Private Jesse Kosier’s remains were initially buried at Weverton, Maryland—as does the National Cemetery Interment Control Form completed by the Office of the Quartermaster General in Washington, D.C. (This latter form, however, contained the incorrect date of death—31 October 1864.)

The National Cemetery Interment Control Form for Private Jesse Kosier, Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, confirms that he died in 1864, was initially buried at Weverton, Maryland, and then exhumed and reinterred at the Antietam National Cemetery.

When the federal government began exhuming and moving Union soldiers’ remains to national cemeteries, Private Jesse Kosier’s remains were exhumed and reinterred at the Antietam National Cemetery in site 3996 in Sharpsburg, Maryland on 31 August.

This notation in the Antietam National Cemetery burial ledgers also confirms the initial burial at Weverton, Maryland, and exhumation and reinterment at Antietam of the remains of Private Jesse Kosier, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Meanwhile, the two surviving Kosier brothers (George and William) did their best to soldier on in the face of their heartache. Attached to the Middle Military Division, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah with their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers from August through November of 1864, it was at this time and place, under the leadership of legendary Union Major-General Philip H. (“Little Phil”) Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, that they would exhibit their greatest moments of valor. Of the experience, C Company Drummer Boy Samuel Pyers later said it was “our hardest engagement.”

First came the Battle of Berryville, Virginia on 3-4 September 1864, which sparked as Confederate troops in the area responded to Major-General Sheridan’s efforts to move his Union troops deeper into the Shenandoah Valley, and then roared into a full-fledged battle as both sides poured more troops into the area. Despite the intensity of the combat, though, the casualty rate was low—roughly 600 total (combined figure for both sides in killed, wounded, captured, or missing soldiers), and the battle is now viewed by many present day historians as a stalemate.

A brief respite in the action from early to mid-September saw the departure of several 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who had served ably, including Company D’s Captain Henry Woodruff, First Lieutenant Samuel Auchmuty, and Sergeants Henry Heikel and Alex Wilson. All departed 18 September 1864 upon expiration of their service terms. Those from the 47th who remained on duty, like the Kosier brothers, were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill, September 1864

Together with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Sheridan and Brigadier-General Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”). The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most critical during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. After finally reaching the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with the Confederate Army commanded by Early. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and the 19th Corps were directed by General William Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as another Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops trying to cross a clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice—once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

The 19th Corps, with the 47th in the thick of things, began pushing the Confederates back. Early’s “grays” retreated in the face of the valor displayed by Sheridan’s “blue jackets.” Leaving 2,500 wounded behind, the Rebels retreated to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September), eight miles south of Winchester, and then to Waynesboro, following a key early morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union men which outnumbered Early’s three to one. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek.

On 22 September 1864, Sergeant George W. Kosier was promoted to the rank of First Lieutenant.

Moving forward, Lieutenant George Kosier and others of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but would do so without two additional respected commanders: Colonel Tilghman Good and his second-in-command, Lieutenant Colonel George Alexander. Both mustered out 23-24 September as their terms expired. They were replaced by others equally admired for their temperament and front line success: Second Lieutenant George Stroop, who was promoted to lead Company D and, at the regimental level, John Peter Shindel Gobin, Charles W. Abbott and Levi Stuber.

Battle of Cedar Creek, October 1864

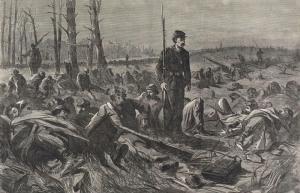

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” which captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle pits, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

During the fall of 1864, Major-General Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by erasing Virginia’s farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents—civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Victorious through most of their encounters with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally and win the day.

From a military standpoint, it was impressive, but heartrending. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men captured Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles—all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he road rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

The Union’s counterattack punched Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

Once again, casualties for the 47th were high. Sergeant William Pyers, the C Company man who had so gallantly rescued the flag at Pleasant Hill was cut down and later buried on the battlefield. Corporal Edward Harper of Company D was wounded, but survived, as did Corporal Isaac Baldwin, who had been wounded earlier at Pleasant Hill. Perry County resident and Regimental Chaplain William Rodrock suffered a near miss as a bullet pierced his cap.

Following these major engagements, the two surviving Kosier brothers and their fellow 47th Volunteers were ordered to Camp Russell near Winchester, where they remained through most of December. On 14 November, Second Lieutenant George Stroop was promoted to the rank of Captain. Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were then ordered to outpost and railroad guard duty at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia five days before Christmas.

1865 – 1866

Assigned to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade, Army of the Shenandoah in February, the men of the 47th moved, via Winchester and Kernstown, back to Washington, D.C. where, on 19 April, they were again responsible for helping to defend the nation’s capital—this time following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. Encamped near Fort Stevens, they received new uniforms and were resupplied.

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865. Note crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half mast following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Letters sent home and later newspaper interviews with survivors of the 47th indicate that at least one member of the 47th Pennsylvania was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train while others may have guarded the Lincoln assassination conspirators during the early days of their imprisonment. As part of Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania also participated in the Union’s Grand Review on 23-24 May.

Captain Levi Stuber of Company I was promoted to the rank of Major with the regiment’s central staff during this time. On 1-2 Jun 1865, First Lieutenant George W. Kosier was promoted to the rank of Captain and leadership of Company D prior to the mustering out of Major George Stroop, who had completed his term of service; Second Lieutenant George W. Clay was promoted to the rank of First Lieutenant.

On their final southern tour, Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers served in Savannah, Georgia from 31 May to 4 June. Again in Dwight’s Division, they were part of the 3rd Brigade, Department of the South. Relieving the 165th New York Volunteers from their duty in Charleston, South Carolina in July, they quartered in the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury.

Ruins seen from the Circular Church, Charleston, South Carolina, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

Guarding the local jails and performing other civil governance in Charleston, South Carolina through the fall and early winter, the majority of D Company men and other 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers finally began to honorably muster out at Charleston, a process which began on Christmas Day and continued through early January. Captain George W. Kosier and his surviving brother, Private William S. Kosier, were two of those who mustered out on 25 December 1865.

Following a stormy voyage home, the 47th Pennsylvania disembarked in New York City. The weary men were then shipped to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader on 9 January 1866, the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were officially given their discharge papers.

Return to Civilian Life—George W. Kosier

Sometime in the mid-1860s, George W. Kosier wed Candace Brooks Chellis. A native of Goshen, New Hampshire, Candace (Chellis) Kosier was born on 3 November 1834. Their first daughter, Lillian A. Kosier, was born in Illinois in September 1864, according to the 1900 federal census.

On 7 April 1870, George and Candace welcomed daughter Helen, who later married William M. Sterling. The 1880 federal census recorded Helen’s name as “Nellie”; in 1880, she resided with her older sister and parents in Byron, Ogle County, Illinois. George was employed as a carpenter during this time.

Daughter Helen married and departed from the Kosier family home before the turn of the century. In 1900, George and Candace were residing with Lillian in Eagle Grove, Wright County, Iowa, where George was employed as a bridge builder. By 1909, the three Kosiers were residing in Chicago, Cook County, Illinois, where George was employed as a “bridge carpenter.”

On 5 January 1914, Candace Kosier widowed her husband, passing away in Chicago. She was interred at Chicago’s Rosehill Cemetery and Mausoleum.

George W. Kosier died in Chicago, Cook County, Illinois on 3 December 1920, and was also interred at the Rosehill Cemetery and Mausoleum in Chicago.

Return to Civilian Life—William S. Kosier

The post-war journey of William S. Kosier is less clear. What is known is that, on 4 April 1880, William S. Kosier’s widow, Mary E. Kosier, filed for her Civil War Widow’s Pension, an indication that her husband had passed away either in 1879 or early 1880.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

2. Crownover, James, et. al., in Camp Ford Prison Records. Tyler, Texas: The Smith County Historical Society, 1864.

3. Krosier, George [sic], in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (D-47 I). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

4. “Florida’s Role in the Civil War,” in Florida Memory. Tallahassee, Florida: State Archives of Florida.

5. George Kosier and Candace Brooks Kosier, in Cook County Deaths, State of Illinois. Springfield, Illinois: Department of Public Health, Division of Vital Records.

6. “Kaseir, Jesse” [sic], in Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, federal burial ledgers and national cemetery interment control forms, 1864. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Office of the Adjutant General (Record Group 94), U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

7. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

8. U.S. Census (Ogle County and Cook County, Illinois: 1880, 1900, 1910). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Adminstration.

8. U.S. Civil War Pension Index:

- Kosier, George (application no.: 1319353, certificate no.: 1097759, filed by the veteran from Iowa on 23 June 1904); and

- Kosier, William S. (application no.: 291461, certificate no.: 331447, filed by the veteran’s widow, “Kosier, Mary E.,” on 4 April 1880).

You must be logged in to post a comment.