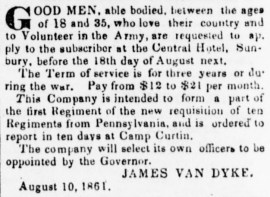

As an authority figure, Sheriff James Van Dyke played a key role in recruiting Northumberland County men for Civil War military service (Sunbury American, 10 August 1861, public domain).

Whether he was convincing the more adventurous residents of Sunbury, Pennsylvania to try oysters for the first time and then incorporate the delicacy into their stews and soups, or delighting hungry Pennsylvania Dutch soldiers with a hard-to-obtain procurement of sauerkraut during the American Civil War, or convincing horse owners across the Great Keystone State to trust him to cure their ailing mares or safely stable their healthier horses, James Van Dyke, Sr. proved to be a resourceful entrepreneur and skilled salesman throughout much of his life.

A patriotic and public service-minded man, he was, perhaps, even better known for his civic leadership as a peace officer in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, and then as Northumberland County Sheriff during the mid-1800s.

Formative Years

Born in Pennsylvania on 27 April 1826, James Van Dyke, Sr. was the husband of Louisa (Bell) Van Dyke (1831-1888). A resident of the borough of Northumberland in Northumberland County, Pennsylvania at the start of the 1850s, it was there that he began his quest to become County Constable. Within a year, he had achieved that objective, having been elected to a one-year term in March of 1851.

A Democrat, politically, he was appointed the following year as one “of 54 delegates to represent the State in the National Democratic Convention to meet at Baltimore,” according to the 13 March 1852 edition of the Sunbury American.

By 1856, he was also flexing his entrepreneurial muscles, partnering with a “Mr. Vandeneker, of Baltimore,” to supply oysters to county residents, according to that year’s 18 October Sunbury American. According to Anthropology Professor Mari Isa, “The fact that oysters were so abundant made them inexpensive, which only boosted their popularity.”

In the United States, one of the largest oyster-producing bodies of water is Chesapeake Bay…. When European colonists arrived in the 17th century, they began to harvest oysters from Chesapeake Bay at a voracious pace.

…. Since oysters do not preserve long once out of their shells, oysters harvested from Chesapeake Bay rarely made it further than could be transported in a day. Nineteenth century advancements in food preservation and transportation transformed the oyster industry. Newly built railways connected the coast with inland cities and made it possible to ship oysters further west. Canning technology made its way to the U.S. in the early 1800s. By the 1840s, oyster canning became a booming business in coastal cities such as Baltimore. Canned oysters and fresh oysters packed in ice were shipped inland to Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, and other Midwest cities.

…. Oysters were used to add bulk to more expensive dishes such as meat pies. They were eaten at breakfast, lunch, and dinner, and by rich and poor alike.

But once again, the siren call of public service would catch his attention and, before one decade could transition to another, James Van Dyke, Sr. was taking on a new role—that of Sheriff of Northumberland County. Per the Saturday, 24 October 1857 Sunbury American:

The new Sheriff, Mr. James Vandyke [sic], entered into bonds on Wednesday last, and will take possession of his office on Wednesday next. His security is ample, and is composed of the following individuals:— Joseph Wallis, Esq., Joseph Vankirk, Peter Hanselman, and J. Vandyke [sic], of Northumberland; Henry S. Neuer and Philip Brymire of Sunbury.

Among his responsibilities was the oversight of sheriff and orphan’s court sales, including a 13 March 1858 sale at John M. Huff’s public house in Milton, which included “[a]ll the right, title and interest of the defendant, of and in a certain lot of ground, situate [sic] in Delaware township … bounded by lands of Christian Gosh, on the north south and east, on the west by the West Branch Canal, containing Four ACRES more or less, whereon are erected a Steam Saw Mill, and Frame House. Seized taken in execution and to be sold as the property of Seth T. McCormick.”

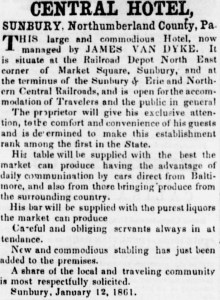

James Van Dyke, Sr.’s advertisment for the Central Hotel in Sunbury, Pennsylvania (Sunbury American, January 1861).

By 1860, he was also the landlord/hotel keeper of the Central Hotel in Sunbury, where he resided with his wife, Louisa, and their children: Margaret (aged 10), James P. (1853-1940), Louisa (aged 4), and Edward (aged 2). Also residing at the hotel at this time were: Mary Gross, a 20-year-old domestic; Samuel P. Smith, a 33-year-old bricklayer; John Wells, a 59-year-old laborer from Germany; and John Smick, a 25-year-old laborer from Poland.

* Note: Originally built by Martin Weaver as a public house on the northeast corner of Sunbury’s Market Square, the building which later became known as the Central Hotel was initially a significantly smaller structure. But by 1859, the pub was transformed into an inn after James Van Dyke, Sr. added a third floor. He continued to operate his establishment until 1865 when he sold the business to Henry Haas.

As the fall of 1860 gave way to winter, James Van Dyke, Sr. and his wife were paying even closer attention to their local newspaper than usual, digesting national news accounts with increasing concern as relations between America’s North and South grew colder. Five days before Christmas, South Carolina seceded from the United States, flinging America into one of the darkest periods in its history.

Civil War

When the worst happened, James Van Dyke, Sr. played a significant part in convincing men from Northumberland County to sign up for military service in response to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers “to maintain the honor, the integrity, and the existence of our National Union, and the perpetuity of popular Government, and to redress wrongs already long enough endured.” In addition to personally encouraging his friends and neighbors to enlist, Van Dyke published his own recruiting advertisement in the 10 August 1861 edition of the Sunbury American, which read:

GOOD MEN, able bodied, between the ages of 18 and 35, who love their country and to Volunteer in the Army, are requested to apply to the subscriber at the Central Hotel, Sunbury, before the 18th day of August next.

The Term of service is for three years or during the war. Pay from $12 to $21 per month.

This company is intended to form a part of the first Regiment of the new requisition of ten Regiments from Pennsylvania, and is ordered to report in ten days at Camp Curtin.

The company will select its own officers to be appointed by the Governor.

JAMES VAN DYKE.

August 10, 1861

Van Dyke then also became one of the county residents who signed up for military service during the first months of the American Civil War. On 18 August 1861, he enrolled in Sunbury, Pennsylvania as a First Lieutenant with Company C (the “Sunbury Guards”) of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. He was then promoted from that position with Company C to a leadership role with the regiment’s central regimental staff either that same day, according to one set of military records, or upon mustering in for duty shortly thereafter, according to others—or on 24 September when the regiment was formally mustered into the United States Army.

What is known for certain is that the new and far more powerful position that he would hold for the duration of his service was Regimental Quartermaster. According to accounting and business management professors Darwin L. King and Carl J. Case, this job was an immensely important one:

A brief review of military organization will provide the reader with more insight into the two basic military cost accounting positions: the Company Accounting Clerk and the Regimental Quartermaster. The Civil War Union Army was organized into corps, divisions, brigades, regiments, and companies (Boatner, 1991). A corps was the largest military unit. It was made up of two or three divisions under the direction of a Major General. A division was composed of three to five brigades … [each of which were] led by a Major General or Senior Brigade General … [and composed] of three to six regiments [led by] … a Brigadier General or a senior Colonel…. A regiment was typically composed of 500 to 1,000 men … [and was typically led by] a Colonel…. Finally, the regiment was broken down into the military’s smallest record keeping unit called a company….

The company or accounting clerk was a position filled by a man who was either a non-commissioned officer or soldier who was known to have good penmanship and a capacity for keeping good reports and records. This basically meant that privates … corporals, or sergeants (non-commissioned officers) were allowed to hold the position of company clerk. Either the commanding officer of the company (i.e. captain) or the first sergeant normally supervised the clerk…. The Company Accounting Clerk represented the heart of cost control for the army during the Civil War.

The next level of cost accounting was at the regimental level. Each quartermaster was responsible for cost records relating to the ten or twelve companies comprising the regiment. Since the quartermasters handled a large amount of cash for making payrolls and purchasing required supplies, regulations required all newly appointed quartermasters to purchase a “good and sufficient bond” in an amount specified by the Secretary of War.

According to Professors King and Case, company clerks were responsible for creating and updating records in their respective regimental morning report books, which detailed “the duty status of each soldier in the company,” and also “described the reason for every officer or soldier not being available for duty,” such as those who had been assigned to the Quartermaster’s department or were “under arrest, away with or without leave, killed in action, wounded, hospitalized, or sick.” In addition, company clerks were also responsible for updating the accounts of company funds, which kept track of cash accounts “utilized by the unit for the purchase of necessities … not furnished by the army … such as the purchase of spices for cooking,” and for keeping current the books documenting “all general orders from the regimental headquarters … [and] any special orders that pertained to the company in general or to a particular member of the unit,” sick books, records of target practice, and descriptive books, which “listed each non-commissioned officer and enlisted men of the company with numerous details pertaining to each man [including] age, height, complexion, eye and hair color, birthplace, occupation, and when, where, and for how long they enlisted,” as well as “character, promotions, appointments, compliments … medals earned [and any] punishments resulting from court-martials.”

And these clerks also played a key role in keeping track of their regiments’ respective expenditures on clothing, arms, and other equipment. King and Case explain that:

The army normally provided the men with their entire first year’s clothing allowance upon enlistment. In following years, the clerk used a monthly allowance to determine if an overdrawn or under drawn situation existed [and if a soldier was overdrawn or was caught selling his clothing, he was expected to pay the army back during a bimonthly payroll muster]….

The Register of Public Property Issued to Soldiers was another book prepared by the accounting clerk … to record all of the rifles, pistols, swords, and other arms issued to each man [as well as] cap-boxes, cartridge-boxes, gun slings, waist belts, and small tools used to maintain the weapons. Soldiers were normally charged for lost arms unless there was a very legitimate reason…. Following a military engagement, the officers of the company were required to inventory arms in the hands of surviving soldiers and collect weapons from soldiers who were either killed or wounded….

* Note: Henry Wharton, a musician from C Company, would ultimately become one of the 47th Pennsylvanians performing the company clerk duties described above and would also become the most frequent chronicler of the 47th Pennsylvania’s activities throughout the long war.

The target practice record book would have been of particular interest to someone like James Van Dyke, Sr. because it was “furnished by the Regimental Quartermaster,” according to Professors King and Case, for use by company clerks in “recording the rifle shooting abilities of each man in the company”:

Each man fired four rounds at distances from 150 to 400 yards. Soldiers with the best accuracy received a company prize, which was a brass medal indicating sharpshooter ability. This book had to be forwarded to the commanding officer of the regiment weekly….

King also notes that “Article XLII define[d] the Quartermaster’s Department as the unit that provide[d] ‘the quarters and transportation of the army, storage and transportation of all army supplies, army clothing, camp and garrison equipage, cavalry and artillery horses, fuel, forage, straw, material for bedding, and stationery,’” adding that:

The Regulations of 1861 … specified a standard amount of barracks and fuel for all officers … [and] the amount of stationery available for all officers. For example, Section 1130 states that an officer commanding a regiment of not less than five companies was allowed a quarterly allotment of ten quires (500 pages) of writing paper, one quire of envelopes, forty quill pens, six ounces of sealing wax, and two rolls of office tape….

…. Section 1148 allows a general three tents, one axe, and one hatchet while in the field. Also, for every fifteen soldiers on foot and every thirteen mounted soldiers, there was allocated one tent, two spades, two axes, two picks, two hatchets, two camp kettles, and five mess pans…. If the unit abused their allotment of equipment, any additional items requested over the standard allowance were billed to the requesting company or regiment.

The subsistence department provided standard cost information on expenditures for the preparation of meals for the men. Notes to Section 1229 of the regulations quote the cost of 100 rations for the soldiers at $11.05. This figure represented detailed cost figures on pork, beef, flour, beans, rice, coffee, tea, sugar, vinegar, candles, soap, and salt. For example, 68 rations of pork were 51 pounds of meat at a standard cost of six cents per pound. The other 32 rations (to make the 100 rations total) was 40 pounds of beef at four cents per pound. The cost of the pork ($3.06) and beef ($1.60) represented a significant portion of the total cost of the rations of $11.05. Feeding all of the soldiers three times daily was a significant expense whose cost was carefully regulated by army headquarters.

These regulations “also included details on the allowed quantities of medicines and equipment for both general and post hospitals.”

The standard quantities allowed were based on the number of men in the post. For example, a post with 500 men was allowed a yearly allotment of 96 bottles of alcohol. This was increased to 192 bottles per year if the post had 1,000 men. This standard allowance table, in addition to medicines, included the yearly allotment of instruments (stethoscopes, syringes, splints, etc.), books, hospital stores, bedding, dressings and related supplies. If a post required additional items, they paid a standard cost for each product ordered over the yearly allotment.

In addition, clothing use was also closely controlled, say King and Case:

Soldiers were allowed, according to Section 1050 of the Regulations of 1861, a certain number of articles of clothing … seven caps, five hats, eight coats, thirteen trousers, fifteen shirts, twenty pairs of socks, and ten pairs of boots over a five year enlistment term….

Both clerks and quartermasters were required to prepare[quarterly] budgets that were called “Estimate of Funds Required” … to determine the funds needed by a company or regiment for muster (payroll), food and rations, ordnance service (including police and preservation of the post and tools and machinery), supplies, and all other materials required by the unit….

But these records maintained by Wharton and Van Dyke were not meant only for “internal consumption” by leaders of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. According to Professors King and Case, “At the regimental level, all reports received from the company clerks were summarized and reviewed for accuracy prior to sending the information to Washington.”

So, early on, during that first Civil War summer, the world of Regimental Quartermaster James P. Van Dyke, Sr. quickly metamorphosed into one that required his attentive monitoring of military minutiae. Regimental records at the time described Van Dyke as being a 35-year-old landlord and resident of Northumberland County who was 5’10” tall with dark hair, gray eyes, and a light complexion.

In addition to becoming enmeshed in the world of cost accounting after officially mustering in at Camp Curtin in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania on 2 September 1861, he and his subordinates also received basic training in light infantry tactics.

Ordered to head south for the District of Columbia just over two weeks later, Regimental Quartermaster Van Dyke and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were transported by train on 20 September 1861 to Washington, D.C. where, beginning 21 September, they were stationed roughly two miles from the White House at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown.

“It is a very fine location for a camp,” wrote C Company Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin. “Good water is handy, while Rock Creek, which skirts one side of us, affords an excellent place for washing and bathing.”

Henry Wharton penned this update for the Sunbury American on 22 September:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on discovering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

I am happy to inform you that our young townsman, Mr. William Hendricks, has received the appointment of Sergeant Major to our Regiment. He made his first appearance at guard mounting this morning; he looked well, done up his duties admirably, and, in time, will make an excellent officer. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

On 24 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were formally mustered into the U.S. Army.

* Note: According to one source, First Lieutenant James P. Van Dyke, Northumberland County’s ex-sheriff, was promoted from the ranks of Company C on this same day in order to assume his job with the regiment’s central command as Regimental Quartermaster. According to historian Samuel P. Bates, however, that promotion had taken place back in August of 1861.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

Three days later, on a rainy 27 September, the 47th Pennsylvania was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania was on the move again. Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen marched behind their regimental band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (165 steps per minute using 33-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated close to the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (also known as “Baldy”), and were now part of the massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

Sometime during this phase of duty, the 47th Pennsylvanians and fellow 3rd Brigade members were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” for the large chestnut tree located within their lodging’s boundaries. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly 10 miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a letter home in mid-October, Captain Gobin reported that the right wing of the 47th Pennsylvania (companies A, C, D, F and I) was ordered to picket duty after the left wing’s companies (B, G, K, E, and H) were forced to return to camp by Confederate troops:

I was ordered to take my company to Stewart’s house, drive the Rebels from it, and hold it at all hazards. It was about 3 o’clock in the morning, so waiting until it was just getting day, I marched 80 men up; but the Rebels had left after driving Capt. Kacy’s company [H] into the woods. I took possession of it, and stationed my men, and there we were for 24 hours with our hands on our rifles, and without closing an eye. I took ten men, and went out scouting within half a mile of the Rebels, but could not get a prisoner, and we did not dare fire on them first. Do not think I was rash, I merely obeyed orders, and had ten men with me who could whip a hundred; Brosius, Piers [sic], Harp and McEwen were among the number. Every man in the company wanted to go. The Rebels did not attack us, and if they had they would have met with a warm reception, as I had my men posted in such a manner that I could have whipped a regiment. My men were all ready and anxious for a “fight.”

In his own letter of this period (on 13 October to the Sunbury American), Henry Wharton described the typical duties of the 47th Pennsylvanians, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

Wharton also reported that all of the men were well; unfortunately, he was proven wrong.

A Sad, Unwanted Distinction

On 17 October 1861, death claimed the first member of the entire regiment—the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ little drummer boy, John Boulton Young. The pain of his loss was deeply and widely felt; Boulty (also spelled as “Boltie”) had become a favorite not just among the men of his own C Company, but of the entire 47th. After contracting Variola (smallpox), he was initially treated in camp, but was shipped back to the Kalorama eruptive fever hospital in Georgetown when it became evident that he needed more intensive care.

According to Lewis Schmidt, author of A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, Captain J. P. S. Gobin wrote to Boulty’s parents, Mr. and Mrs. Mitchell Young of Sunbury, “It is with the most profound feelings of sorrow I ever experienced that I am compelled to announce to you the death of our Pet, and your son, Boulton.” After receiving the news of Boulty’s death, Gobin said that he “immediately started for Georgetown, hoping the tidings would prove untrue.”

Alas! when I reached there I found that little form that I had so loved, prepared for the grave. Until a short time before he died the symptoms were very favorable, and every hope was entertained of his recovery… He was the life and light of our company, and his death has caused a blight and sadness to prevail, that only rude wheels of time can efface… Every attention was paid to him by the doctors and nurses, all being anxious to show their devotion to one so young. I have had him buried, and ordered a stone for his grave, and ere six months pass a handsome monument, the gift of Company C, will mark the spot where rests the idol of their hearts. I would have sent the body home but the nature of his disease prevented it. When we return, however, if we are so fortunate, the body will accompany us… Everything connected with Boulty shall by attended to, no matter what the cost is. His effects that can be safely sent home, together with his pay, will be forwarded to you.

According to Schmidt, Gobin added the following details in a separate letter to friends:

The doctor… told me it was the worst case he ever saw. It was the regular black, confluent small pox… I had him vaccinated at Harrisburg, but it would not take, and he must have got the disease from some of the old Rebel camps we visited, as their army is full of it. There is only one more case in our regiment, and he is off in the same hospital.

Boulty’s death even made the news nationally via Washington newspapers and The Philadelphia Inquirer. Just 13 years old when he died, he was initially interred at the Military Asylum Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Established in August 1861 on the grounds of the Soldiers’ Home, this cemetery was easily viewed from a neighboring cottage that was used as a place of respite by President Abraham Lincoln and his family.

As a result, in letters home later that month, Captain Gobin asked Sunbury residents to donate blankets for the Sunbury Guards:

The government has supplied them with one blanket apiece, which, as the cold weather approaches, is not sufficient…. Some of my men have none, two of them, Theodore Kiehl and Robert McNeal, having given theirs to our lamented drummer boy when he was taken sick… Each can give at least one blanket, (no matter what color, although we would prefer dark,) and never miss it, while it would add to the comfort of the soldiers tenfold. Very frequently while on picket duty their overcoats and blankets are both saturated by the rain. They must then wait until they can dry them by the fire before they can take their rest.

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th participated in a Divisional Review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” By early November, Gobin was reporting that “the health of the Company and Regiment are in the best condition. No cases of small pox have appeared since the death of Boultie.”

Half of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, including Company C, were next ordered to join parts of the 33rd Maine and 46th New York in extending the reach of their division’s picket lines, which they did successfully to “a half mile beyond Lewinsville,” according to Gobin. In another letter home on 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review overseen by the regiment’s founder, Colonel Tilghman Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to historian Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges…. After the reviews and inspections, Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ outstanding performance during this review and in preparation for the even bigger adventures yet to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan directed his staff to ensure that new Springfield rifles were obtained and distributed to every member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Also during this time, according to Schmidt, Captain Gobin helped a number of Sunbury Guardsmen to send money from their pay back home to their families and friends in Pennsylvania.

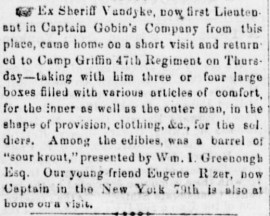

Regimental Quartermaster James VanDyke, Sr. procured a holiday surprise for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers for their first Christmas away from home (Sunbury American, 21 December 1861, public domain).

In December, Regimental Quartermaster James P. Van Dyke, who was enjoying an approved furlough at home in Sunbury, Pennsylvania, was able to procure “various articles of comfort, for the inner as well as the outer man,” according to the 21 December 1861 edition of the Sunbury American. Upon his return to camp, many of the 47th Pennsylvanians of German heritage were pleasantly surprised to learn that the former sheriff of Sunbury had thoughtfully brought a sizable supply of sauerkraut with him. The German equivalent of “comfort food,” this favored treat warmed stomachs and lifted more than a few spirits that first cold winter away from loved ones.

1862

But military service was clearly not a life that Regimental Quartermaster James P. Van Dyke desired. So, barely two weeks into the New Year, he resigned his commission on 16 January 1862—while his regiment was still engaged in defending the nation’s capital—and just before the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would be shipped to America’s Deep South and their first true combat experiences.

Return to Civilian Life

The Central Hotel, Sunbury, Pennsylvania roughly five years after its 1865 sale by James Van Dyke to Henry Haas (circa 1870, public domain).

Following his resignation, James P. Van Dyke, Sr. returned home to Sunbury, Pennsylvania, where he continued to operate the Central Hotel. Over time, however, his previously successful business efforts were gradually eroded by the difficulties caused by the war-time economy. So, in 1865, he sold his hotel to Henry Haas.

Three weeks before Christmas in 1867, the Sunbury American carried the surprising news that “on the 5th day of December. A. D. 1867, a Warrant in Bankruptcy was issued against the Estate of James Van Dyke, of Northumberland, in the County of Northumberland, and State of Pennsylvania, who has been adjudged a Bankrupt, on his own petition.” Bankruptcy proceedings were reportedly scheduled for 12 February 1868 in the Court of Bankruptcy in Sunbury.

But by 1870, his fortunes appeared to have rebounded somewhat because the federal census enumerator who had arrived in Sunbury that year described James Van Dyke, Sr. as a “Gentleman.” Residing in the elder Van Dyke’s home that year were his wife, Louisa, and their children: James, Jr. (aged 17), Louisa (aged 15), and Edward (aged 12).

Three years later, he opened an equine veterinary service, according to the 18 July edition of that year’s Sunbury American newspaper, which ran the following advertisement:

Boarding and Sale Stable.

SHERIFF VAN DYKE has opened a Veterinary Boarding and Sale Stable. Boarding horses that are well will be kept in different stables from those that are sick. Strict attention will be paid to all horses well or sick. I will cure all bad vices in the horse, all diseases of the mouth, all diseases of the respiratory organs, disease of the stomach, liver, urinary organs, feet and legs. Also diseases of the head, eyes, and all missiellaneous [sic] diseases. All surgical cases, such as Bleeding, Nerving, Bowelling, Firing tenotomy, Tapping the chest, coucting, &c. &c. Also, Trotting horses trained for the course. Stable back if Central Hotel. JAMES VAN DYKE July 19, ’73.—St.

By mid-decade, however, James Van Dyke, Sr. had thrown his hat back into the political arena. In 1875, he won the race for Constable of Sunbury’s West Ward, garnering 120 votes to the 112 and 84 votes secured, respectively, by G. W. Stroh and Samuel Gerringer. Still serving as Constable in Sunbury in 1880, his household that year included only his wife, Louisa, and their 23-year-old daughter, Louisa. Sadly, this stability would be short lived.

Death and Interment

On 30 March 1881, James Van Dyke, Sr. passed away in Sunbury, Northumberland County on 30 March 1881, and was interred at the city cemetery in Sunbury.

What Happened to the Family of James Van Dyke, Sr.?

James Van Dyke’s widow, Louisa, continued on without her husband for roughly seven more years before passing away in Northumberland County on 5 October 1881. She was then laid to rest beside her husband at the Sunbury Cemetery. A large obelisk marks their family’s cemetery plot.

James Van Dyke’s son, James Parker Van Dyke, Jr., who had been born in Sunbury on 17 September 1853, grew up to become a long-time druggist in Sunbury, Pennsylvania, helping to heal ailing members of his community until he retired from practice sometime during the mid to late 1930s. In declining health, due to complications from heart disease, he died in Sunbury, Pennsylvania on 30 April 1940, and was laid to rest at a cemetery there on 2 May.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Bell, Herbert C. History of Northumberland County, Pennsylvania, Including Its Aboriginal History; the Colonial and Revolutionary Periods; Early Settlement and Subsequent Growth; Political Organization; Agricultural, Mining, and Manufacturing Interests; Internal Improvements; Religious, Educational, Social, and Military History; Sketches of Its Boroughs, Villages, and Townships; Portraits and Biographies of Pioneers and Representative Citizens, Etc., Etc. Chicago, Illinois: Brown, Runk, & Co. Publishers: 1891.

- “Boarding and Sale Stable.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 19 July 1873.

- Burial Record (James VanDyke). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: First Presbyterian Church, 1881.

- “Central Hotel.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 19 January 1861.

- Consolidated Lists of Civil War Draft Registrations, U.S. Provost Marshal General’s Bureau (Civil War, Record Group 110). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives.

- “Constables, The.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 29 March 1851.

- Civil War Muster Rolls and Related Records, 1861–1866 (Van Dyke, James). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs (Record Group 19, Series 19.11), Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1865 (Van Dyke, James, F&S-47 I). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Death Certificate: James VanDyke (James VanDyke, Jr.; registered no. 96, 30 April 1940), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Vital Statistics.

- “Election, The.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 19 February 1875.

- “Estate of George Brosious, deceased.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 27 February 1858.

- “Estate of Jacob Jarrett, deceased.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 18 June 1859.

- “Estate of Samuel Moore, deceased.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 14 May 1859.

- History of Northumberland Co., Pennsylvania, With Illustrations Descriptive of Its Scenery, Palatial Residences, Public Buildings, Fine Blocks, and Important Manufactories, pp. 25 and 48-49. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Everts & Stewart, 1876.

- Isa, Mari. “The Great Oyster Craze: Why 19th Century Americans Loved Oysters.” East Lansing, Pennsylvania: Campus Archaeology Program, Michigan State University, 23 February 2017.

- King, Darwin L. and Carl J. Case. “Civil War Accounting Procedures and Their Influence on Current Cost Accounting Practices,” in the Journal of the American Society of Business and Behavioral Sciences (ASBBS), vol. 3, no. 1, 2007.

- “New Sheriff, The.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 24 October 1857.

- “Notice in Bankruptcy.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 28 December 1867.

- “Orphans’ Court Sale.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1 September 1860.

- Our Town: Interesting Facts in Its History. Northumberland, Pennsylvania: Northumberland Junior History Club, vol. III, edition I, 1946.

- “Oysters.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 18 October 1856.

- Pennsylvania Veterans’ Burial Index Card (Van Dyke, James). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs.

- “Register of Communicants” (March 1881 death entry for James Van Dyke). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: First Presbyterian Church.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “Sheriff Sales.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 11 June 1859.

- “Sheriff’s Sale.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: 5, 20 February 1858.

- “State Convention, The.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 13 March 1852.

- Thorell, Margaret Murray. Sunbury, p. 49. Charleston, South Carolina: Arcadia Publishing, 2014.

- U.S. Census (1860, 1870, 1880). Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Wm. Van Dyke, son of James Parker Van Dyke and Rose Mae Bartholomew (and grandson of James Van Dyke) in “Death Certificates (registered no. 88, 10 March 1909). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania: Bureau of Vital Statistics.

You must be logged in to post a comment.