Colonel Tilghman H. Good, founder and commanding officer, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (public domain).

Born in South Whitehall Township in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania on 6 October 1830, Tilghman H. Good was the son of South Whitehall native and farmer James Good (1804-1838) and Mary (Blumer) Good. (James was a son of Henry Good, who had taken up farming in South Whitehall after emigrating from Switzerland to the United States, while Mary was the daughter of Rev. Abraham Blumer, the Zion Reformed Church pastor who had won the love and respect of his fellow Patriots for providing a haven for the Liberty Bell after it was moved north to keep it from falling into the hands of General William Howe’s British troops after they had entered and occupied Philadelphia during the Revolutionary War.)

An active member of the Knights Templar and Masons throughout much of his life, Tilghman H. Good was devoted to the betterment of his community and nation. As the founder and commanding officer of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, he led his men in intense Civil War battles which helped preserve the Union of America. Elected to serve as a member of the Pennsylvania State Legislature, he was also a three-term mayor of Allentown, Pennsylvania.

Early Years

During his formative years, Tilghman Good resided in South Whitehall Township with his parents, brothers Edwin and James, and sisters: Caroline, who later married William Reinsmith; Sarah, who later married Rufus Snyder; and Henrietta, who later married Russell Thayer.

Tragically, four days before Christmas in 1838, the life of eight-year-old Tilghman was upended when his 34-year-old father passed away. As a result, he was sent to live with his uncle, Peter Blank. Here, he spent his days working on the family farm when not attending school. Apprenticed to a shoemaker at the age of 16, he was then employed in the boot and shoe business from the mid-1840s until 1849, first in Philadelphia and then in Allentown, Lehigh County.

Trying out a different pursuit as the landlord of the Allen House beginning in 1849, he also became a family man when he married Mary Trexler, on 6 April 1851. A resident of Allentown, she was the daughter of Amandus Trexler. Together, Tilghman and Mary Good had one child; sadly, that child did not survive infancy.

By 1853, Tilghman Good was employed once again as a shoemaker. Six years later, he secured a position as a teller with the Allentown Bank, a job he held for four years. He then became a hat and shoe salesman.

Military Service and Elected Office

In addition to his business ventures, Tilghman Good also pursued a parallel career—that of military man. On 10 July 1850, he was named as the Captain of the Allen Rifles, a new militia unit formed in response to the dissolution of the Lehigh Fencibles. In short order, he became known as “one of the ablest tacticians in the State of Pennsylvania.” His men “wore regulation blue uniforms, carried Minie rifles,” and under his instruction, “attained a degree of proficiency in Hardee’s tactics and the Zouave drill which won for them a reputation extending beyond the borders of the state,” according to Lehigh County historians who later reported on his formative years.

Serving as Captain of the Allen Rifles until 1857, Tilghman Good also served as brigade inspector for Lehigh County until 1861, as well as commander of the 4th Regiment, Pennsylvania National Guard.

In 1858, he was also elected to serve in the Pennsylvania State Legislature.

The Civil War — Three Months’ Service

Alma Pelot’s photo showing the Confederate flag flying over Fort Sumter, 16 April 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Two days before the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces and President Abraham Lincoln’s resulting call for volunteer troops to help defend the nation’s capital, residents of the Lehigh Valley “called a public meeting at Easton ‘to consider the posture of affairs and to take measures for the support of the National Government,’” according to Alfred Mathews and Austin N. Hungerford, authors of History of the Counties of Lehigh and Carbon, in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. At that time, those citizens voted to establish an entirely new military unit—the 1st Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, and also voted to place Tilghman H. Good in charge of that regiment’s Company I, assigning him the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel. Captain Samuel Yohe of Easton was appointed Colonel of the 1st Pennsylvania Volunteers, and Thomas W. Lynn was awarded the rank of Major.

The Allen Rifles were then incorporated into the 1st Pennsylvania Volunteers, mustering into service at Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, Dauphin County on 20 April 1861. Although officially known as Company I, the 81 officers and men of this particular company were still frequently referred to by their long-standing designation (the “Allen Rifles”).

Tilghman Good also enrolled for service on 20 April, at the age of 30 at Allentown, and mustered in as Lieutenant-Colonel of the regiment at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County the same day.

Upon fulfillment of their Three Months’ Service, Good and the other men of Company I were honorably discharged, with most mustering out at Harrisburg on 23 July 1861 and Good mustering out on 27 July. Many still loyal to Good, their former “Allen Rifles” captain and 1st Regiment commanding officer, answered the call to arms yet again just weeks later as Good began recruiting for the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry—the regiment he founded. This time, they would be in service for the long haul and headed deeper into Confederate territory than they could have ever imagined.

Three Years’ Service with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers

Re-enrolling for duty as Commanding Officer of the 47th Regiment of the Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry at Camp Curtin in August 1861, Tilghman H. Good oversaw the mustering in and training of his troops from late August through early September. Following instruction in light infantry tactics with Mississippi rifles supplied by their beloved Keystone State, the 47th Pennsylvania was transported by train to Washington, D.C. The regiment was stationed at “Camp Kalorama” at Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, roughly two miles from the White House, beginning 21 September.

The next day, C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton penned the following update for the Sunbury American newspaper:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

On 24 September 1861, Company C and the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were formally mustered into the U.S. Army. Three days later, on a rainy 27 September, the men enjoyed a drill-free morning, writing letters home and reading, as Good and his officers were learning that their regiment was being assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens. By afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania was on the move again, under marching orders to head for Camp Lyon, Maryland on the eastern side of the Potomac River.

Arriving late that afternoon, they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in charging double-quick across the Chain Bridge, marching onto Confederate soil and on toward Falls Church, Virginia. By dusk, after tramping roughly eight miles that day, they pitched their tents in a deep ravine at Camp Advance near the Union’s new Fort Ethan Allen (still being completed) and the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith, commander of the Union’s massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Their job was to help defend the nation’s capital.

In October, the 47th was ordered to proceed with the 3rd Brigade to Camp Griffin. On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th participated in a Divisional Review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.”

Half of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were next ordered to join parts of the 33rd Maine and 46th New York in extending the reach of their division’s picket lines, which they did successfully to “a half mile beyond Lewinsville,” according to John Peter Shindel Gobin, captain of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Company C.

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review overseen by Colonel Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to historian Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges…. After the reviews and inspections, Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

At the close of the year, they received orders from the 3rd Brigade’s commander, Brigadier-General Brannan, to head for Key West, Florida. Quartered briefly at the barracks at Annapolis, Maryland, Colonel Good and his 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers departed on 27 January 1862 via the steamer Oriental.

They arrived in Florida in February 1862, and were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor, one of several federal installations in the state that were deemed strategically important by Union leaders. Although Florida had seceded from the Union in 1861, it remained home to a fair number of Union supporters, including enslaved men and women who were fleeing their captors.

On 14 February 1862, Colonel Good and his 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers made their presence known to the residents of Key West during a parade through the streets of the city. That weekend, a number of men from the regiment mingled with members of the community as they attended local church services in town.

While here, the men of the 47th drilled in heavy artillery and other battle strategies—often as much as eight hours per day. Their time here was also difficult due to the prevalence of disease. Many of the 47th’s men lost their lives to typhoid fever, or to dysentery and other ailments spread from soldier to soldier by poor sanitary conditions.

But there were lighter moments as well. According to a letter penned by Henry Wharton on 27 February 1862, the regiment commemorated the birthday of former U.S. President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation and the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February. The festivities then continued two days later when the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards.” This was then followed by a concert by the regimental band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

Ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina from mid-June through July, the 47th Pennsylvania camped near Fort Walker and then quartered in the Beaufort District, Department of the South. Duties of 3rd Brigade members at this time involved hazardous picket duty to the north of their main camp. According to Pennsylvania military historian, Samuel P. Bates, the 47th’s soldiers were known for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” and “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan.”

Meanwhile, back in Washington, D.C., the bean counters were busy tallying up the costs of a war now entering its second year. Deeming regimental bands an unnecessary expense in light of rising federal expenses, the U.S. Congress passed legislation on 17 July 1862 ordering that all such bands bands be promptly, but honorably mustered out. Signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln, the U.S. War Department effected this change via General Order 91, issued on 29 July 1862. As the musicians of Regimental Band, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry packed and readied for their return home in early September 1862, Colonel Tilghman H. Good, expressed both disappointment and respect in a letter to the ensemble:

Headquarters 47th Regt. P.V.

Beaufort, S.C., Sept. 9, 1862Gentlemen of the Band,

In accordance with an enactment of Congress and an order from the War Department, you have been regularly mustered out of the service of the United States, and are consequently detached from the regiment. I had vainly hoped when you were with us, united to do battle for our country, that we should remain together, to share the dangers and reap the same glory, until every vestige of the present wicked rebellion should be forever crushed, and we unitedly return again to our homes in peace, and receive of our fellow creatures the welcome plaudit, ‘well done’.

But fate has decreed otherwise, and you are about to bid ‘farewell’, and in taking leave of you, gentlemen, I beg leave to compliment you on your good deportment and manly bearings whilst connected with the regiment, and when you shall have departed from amongst us the sweet strains of music which emanated from you and so often swelled the breeze during dress parade, shall still ring in our ears.

Invoking heaven’s choicest gifts upon you collectively and individually, I bid you god speed on your homeward voyage and through all your future career. May your future course through life be as bright and happy as your past has been prosperous and safe.

I am, Gents,

Your obedient servant,

T. H. Good

Col. 47th Regt. Penna. Vols.

Union Navy base of operations, Mayport Mills, circa 1862 (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, public domain).

On 30 September, the 47th made a return expedition to Florida where it participated with other Union forces from 1 to 3 October in capturing Saint John’s Bluff. Led by Brigadier-General Brannan, the 1,500-plus Union force disembarked from gunboat-escorted troop carriers at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek. With the 47th Pennsylvania in the lead and braving alligators, skirmishing Confederates and killer snakes, the brigade negotiated 25 miles of thickly forested swamps in order to capture the bluff and pave the way for the Union’s occupation of Jacksonville, Florida.

In Good’s Own Words—Saint John’s Bluff

In his report on the matter, filed from Mount Pleasant Landing, Florida on 2 October 1862, Tilghman H. Good described the Union Army’s assault on Saint John’s Bluff:

In accordance with orders received I landed my regiment on the bank of Buckhorn Creek at 7 o’clock yesterday morning. After landing I moved forward in the direction of Parkers plantation, about 1 mile, being then within about 14 miles of said plantation. Here I halted to await the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut Regiment. I advanced two companies of skirmishers toward the house, with instructions to halt in case of meeting any of the enemy and report the fact to me. After they had advanced about three-quarters of a mile they halted and reported some of the enemy ahead. I immediately went forward to the line and saw some 5 or 6 mounted men about 700 or 800 yards ahead. I then ascended a tree, so that I might have a distinct view of the house and from this elevated position I distinctly saw one company of infantry close by the house, which I supposed to number about 30 or 40 men, and also some 60 or 70 mounted men. After waiting for the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut Volunteers until 10 o’clock, and it not appearing, I dispatched a squad of men back to the landing for a 6-pounder field howitzer which had been kindly offered to my service by Lieutenant Boutelle, of the Paul Jones. This howitzer had been stationed on a flat-boat to protect our landing. The party, however, did not arrive with the piece until 12 o’clock, in consequence of the difficulty of dragging it through the swamp. Being anxious to have as little delay as possible, I did not await the arrival of the howitzer, but at 11 a.m. moved forward, and as I advanced the enemy fled.

After reaching the house I awaited the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut and the howitzer. After they arrived I moved forward to the head of Mount Pleasant Creek to a bridge, at which place I arrived at 2 p.m. Here I found the bridge destroyed, but which I had repaired in a short time. I then crossed it and moved down on the south bank toward Mount Pleasant Landing. After moving about 1 mile down the bank of the creek my skirmishing companies came upon a camp, which evidently had been very hastily evacuated, from the fact that the occupants had left a table standing with a sumptuous meal already prepared for eating. On the center of the table was placed a fine, large meat pie still warm, from which one of the party had already served his plate. The skirmishers also saw 3 mounted men leave the place in hot haste. I also found a small quantity of commissary and quartermasters stores, with 23 tents, which, for want of transportation, I was obliged to destroy. After moving about a mile farther on I came across another camp, which also indicated the same sudden evacuation. In it I found the following articles … breech-loading carbines, 12 double-barreled shot-guns, 8 breech-loading Maynard rifles, 11 Enfield rifles, and 96 knapsacks. These articles I brought along by having the men carry them. There were, besides, a small quantity of commissary and quartermasters stores, including 16 tents, which, for the same reason as stated, I ordered to be destroyed. I then pushed forward to the landing, where I arrived at 7 p.m.

We drove the enemys [sic] skirmishers in small parties along the entire march. The march was a difficult one, in consequence of meeting so many swamps almost knee-deep.

On 3 October, Good filed his report from Saint John’s Bluff, Florida, now in Union hands:

At 9 o’clock last night Lieutenant Cannon reported to me that his command, consisting of one section of the First Connecticut Battery, was then coming up the creek on flat-boats with a view of landing. At 4 o’clock this morning a safe landing was effected [sic] and the command was ready to move. The order to move to Saint John’s Bluff reached me at 4 p.m. yesterday. In accordance with it I put the column in motion immediately and moved cautiously up the bank of the Saint John’s River, the skirmishing companies occasionally seeing small parties of the enemy’s cavalry retiring in our front as we advanced. When about 2 miles from the bluff the left wing of the skirmishing line came upon another camp of the enemy, which, however, in consequence of the lateness of the hour, I did not take time to examine, it being then already dark.

After my arrival at the bluff, it then being 7:30 o’clock, I dispatched Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander with two companies back to the last-named camp (which I found, from a number of papers left behind, to have been called Camp Hopkins and occupied by the Milton Artillery, of Florida) to reconnoiter and ascertain its condition. Upon his return he reported that from every appearance the skedaddling of the enemy was as sudden as in the other instances already mentioned, leaving their trunks and all the camp equipage behind; also a small store of commissary supplies, sugar, rice, half barrel of flour, one bag of salt, &c., including 60 tents which I have brought in this morning. The commissary stores were used by the troops of my command.

Integration of the Regiment

On 5 and 15 October 1862, respectively, the military unit founded by Colonel Tilghman Good made history as the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry became an integrated regiment, adding to its muster rolls several young to middle-aged Black men who had been freed from enslavement on plantations in the vicinity of Beaufort, South Carolina:

- Just 16 years old at the time of his enlistment, Abraham Jassum joined the 47th Pennsylvania from a recruiting depot on 5 October 1862. Military records indicate that he mustered in as “negro undercook” with Company F at Beaufort, South Carolina. Military records described him as being 5 feet 6 inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, and stated that his occupation prior to enlistment was “Cook.” Records also indicate that he continued to serve with F Company until he mustered out at Charleston, South Carolina on 4 October 1865 when his three-year term of enlistment expired.

- Also signing up as an Under Cook that day at the Beaufort recruiting depot was 33-year-old Bristor Gethers. Although his muster roll entry and entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File in the Pennsylvania State Archives listed him as “Presto Gettes,” his U.S. Civil War Pension Index listing spelled his name as “Bristor Gethers” and his wife’s name as “Rachel Gethers.” This index also includes the aliases of “Presto Garris” and “Bristor Geddes.” He was described on military records as being 5 feet 5 inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, and as having been employed as a fireman. He mustered in as “Negro under cook” with Company F on 5 October 1862, and mustered out at Charleston, South Carolina on 4 October 1865 upon expiration of his three-year term of service. Federal records indicate that he and his wife applied for his Civil War Pension from South Carolina.

- Also attached initially to Company F upon his 15 October 1862 enrollment with the 47th Pennsylvania, 22-year-old Edward Jassum was assigned kitchen duties. Records indicate that he was officially mustered into military service at the rank of Under Cook with the 47th Pennsylvania at Morganza, Louisiana on 22 June 1864, and then transferred to Company H on 11 October 1864. Like Abraham Jassum, Edward Jassum also continued to serve with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers until being honorably discharged on 14 October 1865 upon expiration of his three-year term of service.

More men of color would continue to be added to the 47th Pennsylvania’s rosters in the weeks and years to come.

In Good’s Own Words—the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

Colonel Good and the 10th Army next engaged Confederate forces in intense fighting during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina from 21 to 23 October. In his report on the engagement, made from headquarters at Beaufort, South Carolina on 24 October 1862, Colonel Good wrote:

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following report of the part taken by the Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers in the action of October 22:

Eight companies, comprising 480 men, embarked on the steamship Ben De Ford, and two companies, of 120 men, on the Marblehead, at 2 p.m. October 21. With this force I arrived at Mackays Landing before daylight the following morning. At daylight I was ordered to disembark my regiment and move forward across the first causeway and take a position, and there await the arrival of the other forces. The two companies of my regiment on board of the Marblehead had not yet arrived, consequently I had but eight companies of my regiment with me at this juncture.

At 12 m. I was ordered to take the advance with four companies, one of the Forty-seventh and one of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania Volunteers, and two of the Sixth Connecticut, and to deploy two of them as skirmishers and move forward. After moving forward about 2 miles I discerned some 30 or 40 of the enemys [sic] cavalry ahead, but they fled as we advanced. About 2 miles farther on I discovered two pieces of artillery and some cavalry, occupying a position about three-quarters of a mile ahead in the road. I immediately called for a regiment, but seeing that the position was not a strong one I made a charge with the skirmishing line. The enemy, after firing a few rounds of shell, fled. I followed up as rapidly as possible to within about 1 mile of Frampton Creek. In front of this stream is a strip of woods about 500 yards wide, and in front of the woods a marsh of about 200 yards, with a small stream running through it parallel with the woods. A causeway also extends across the swamp, to the right of which the swamp is impassable. Here the enemy opened a terrible fire of shell from the rear, of the woods. I again called for a regiment, and my regiment came forward very promptly. I immediately deployed in line of battle and charged forward to the woods, three companies on the right and the other five on the left of the road. I moved forward in quick-time, and when within about 500 yards of the woods the enemy opened a galling fire of infantry from it. I ordered double-quick and raised a cheer, and with a grand yell the officers and men moved forward in splendid order and glorious determination, driving the enemy from this position.

On reaching the woods I halted and reorganized my line. The three companies on the right of the road (in consequence of not being able to get through the marsh) did not reach the woods, and were moved by Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander by the flank on the causeway. During this time a terrible fire of grape and canister was opened by the enemy through the woods, hence I did not wait for the three companies, but immediately charged with the five at hand directly through the woods; but in consequence of the denseness of the woods, which was a perfect matting of vines and brush, it was almost impossible to get through, but by dint of untiring assiduity the men worked their way through nobly. At this point I was called out of the woods by Lieutenant Bacon, aide-de-camp, who gave the order, ‘The general wants you to charge through the woods.’ I replied that I was then charging, and that the men were working their way through as fast as possible. Just then I saw the two companies of my regiment which embarked on the Marblehead coming up to one of the companies that was unable to get through the swamp on the right. I went out to meet them, hastening them forward, with a view of re-enforcing the five already engaged on the left of the road in the woods; but the latter having worked their way successfully through and driven the enemy from his position, I moved the two companies up the road through the woods until I came up with the advance. The two companies on the right side of the road, under Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander had also worked their way up through the woods and opened fire on the retreating enemy. At this point I halted and reorganized my regiment, by forming close column by companies. I then detailed Lieutenant Minnich, of Company B, and Lieutenant Breneman, of Company H, with a squad of men, to collect the killed and wounded. They promptly and faithfully attended to this important duty, deserving much praise for the efficiency and coolness they displayed during the fight and in the discharge of this humane and worthy trust.

The casualties in this engagement were 96. Captain Junker of Company K; Captain Mickley, of Company I [sic], and Lieutenant Geety, of Company H, fell mortally wounded while gallantly leading their respective companies on.

I cannot speak too highly of the conduct of both officers and men. They all performed deeds of valor, and rushed forward to duty and danger with a spirit and energy worthy of veterans.

The rear forces coming up passed my regiment and pursued the enemy. When I had my regiment again placed in order, and hearing the boom of cannon, I immediately followed up, and, upon reaching the scene of action, I was ordered to deploy my regiment on the right side of the wood, move forward along the edge of it, and relieve the Seventh Connecticut Regiment. This I promptly obeyed. The position here occupied by the enemy was on the opposite side of the Pocotaligo Creek, with a marsh on either side of it, and about 800 yards distant from the opposite wood, where the enemy had thrown up rifle pits all along its edge.

On my arrival the enemy had ceased firing; but after the lapse of a few minutes they commenced to cheer and hurrah for the Twenty-sixth South Carolina. We distinctly saw this regiment come up in double-quick and the men rapidly jumping into the pits. We immediately opened fire upon them with terrible effect, and saw their men thinning by scores. In return they opened a galling fire upon us. I ordered the men under cover and to keep up the fire. During this time our forces commenced to retire. I kept my position until all our forces were on the march, and then gave one volley and retired by flank in the road at double-quick about 1,000 yards in the rear of the Seventh Connecticut. This regiment was formed about 1,000 yards in the rear of my former position. We jointly formed the rear guard of our forces and alternately retired in the above manner.

My casualties here amounted to 15 men.

We arrived at Frampton (our first battle ground) at 8 p.m. Here my regiment was relieved from further rear-guard duty by the Fourth New Hampshire Regiment. This gave me the desired opportunity to carry my dead and wounded from the field and convey them back to the landing. I arrived at the above place at 3 o’clock the following morning.

In a second report made from Beaufort on 25 October 1862, Colonel Good added the following details:

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following report of the part taken by the First Brigade in the battles of October 22:

After meeting the enemy in his first position he was driven back by the skirmishing line, consisting of two companies of the Sixth Connecticut, one of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, and one of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania, under my command. Here the enemy only fired a few rounds of shot and shell. He then retreated and assumed another position, and immediately opened fire. Colonel Chatfield, then in command of the brigade, ordered the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania forward to me, with orders to charge. I immediately charged and drove the enemy from the second position. The Sixth Connecticut was deployed in my rear and left; the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania on my right, and the Fourth New Hampshire in the rear of the Fifty-fifth, both in close column by divisions, all under a heavy fire of shell and canister. These regiments then crossed the causeway by the flank and moved close up to the woods. Here they were halted, with orders to support the artillery. After the enemy had ceased firing the Fourth New Hampshire was ordered to move up the road in the rear of the artillery and two companies of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania to follow this regiment. The Sixth Connecticut followed up, and the Fifty-fifth moved up through the woods. At this juncture Colonel Chatfield fell, seriously wounded, and Lieutenant-Colonel Speidel was also wounded.

The casualties in the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania amounted to 96 men. As yet I am unable to learn the loss of the entire brigade.

The enemy having fled, the Fourth New Hampshire and the Fifty- fifth Pennsylvania followed in close pursuit. During this time the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania and the Sixth Connecticut halted and again organized, after which they followed. On coming up to the engagement I assumed command of the brigade, and found the forces arranged in the following order: The Fourth New Hampshire was deployed as skirmishers along the entire front, and the Fifty-fifth deployed in line of battle on the left side of the road, immediately in the rear of the Fourth New Hampshire. I then ordered the Sixth Connecticut to deploy in the rear of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania and the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania to deploy on the right side of the road in line of battle and relieve the Seventh Connecticut. I then ordered the Fourth New Hampshire, which had spent all its ammunition, back under cover on the road in the woods. The enemy meantime kept up a terrific fire of grape and musketry, to which we replied with terrible effect. At this point the orders were given to retire, and the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania and Seventh Connecticut formed the rear guard. I then ordered the Thirty-seventh Pennsylvania to keep its position and the Sixth Connecticut to march by the flank into the road and to the rear, the Fourth New Hampshire and Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania to follow. The troops of the Second Brigade were meanwhile retiring. After the whole column was in motion and a line of battle established by the Seventh Connecticut about 1,000 yards in the rear of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania I ordered the Forty-seventh to retire by the flank and establish a line of battle 1,000 yards in the rear of the Seventh Connecticut; after which the Seventh Connecticut moved by the flank to the rear and established a line of battle 1,000 yards in the rear of the Forty seventh, and thus retiring, alternately establishing lines, until we reached Frampton Creek, where we were relieved from this duty by the Fourth New Hampshire. We arrived at the landing at 3 o’clock on the morning of the 23d instant.

The casualties of the Sixth Connecticut are 34 in killed and wounded and the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania 112 in killed and wounded. As to the remaining regiments I have as yet received no report.

On 23 October, the 47th Pennsylvania headed back to Hilton Head, where it was awarded the high honor of firing the salute over the grave of General Ormsby M. Mitchel, the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South who had died of yellow fever on 30 October. (The town of Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s self-governed community created after the Civil War, was later named for him.)

On 1 November 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania helped another Black man escape from slavery near Beaufort when they added 30-year-old Thomas Haywood to the kitchen staff of Company H. Described as a 5 feet 4 inch-tall laborer with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, Haywood was officially mustered in as an Under Cook at Morganza, Louisiana on 22 June 1864, and served until the expiration of his own three-year term of service on 31 October 1865.

From 15 November 1862 through February 1864, Good and the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were again assigned to garrison duty, and Good was also placed in command of Brigadier-General Brannan’s regiments on Port Royal Island. (In a 7 March 1863 letter to the Sunbury American, Henry Wharton would confirm Colonel Good’s elevated status, noting: “To be sure he is only acting Brigadier, but before long, we are sure he will wear the star, by right, and no man better deserves it.”)

In mid to late December 1862, Brannan assigned Colonel Good, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander and Major William Gausler of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to serve on a judicial panel with other Union Army officers to conduct the court martial trial of Colonel Richard White of the 55th Pennsylvania Volunteers, and also appointed Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin of the 47th Pennsylvania’s C Company as Judge Advocate for the proceedings. According to a report in the 16 December edition of The New York Herald:

A little feud [had] arisen in Beaufort between General Saxton and the forces of the Tenth Army corps. Last week, during the absence at Fernandina of General Brannan and Colonel Good, the latter of whom is in command of the forces on Port Royal Island, Colonel Richard White of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania, was temporarily placed in authority. By his command a stable, used by some of General Saxton’s employes [sic], was torn down. General Saxton remonstrated, and … hard words ensued … the General presumed upon his rank to place Colonel White in arrest, and to assume the control of the military forces. Upon General Brannan’s return, last Monday, General [Rufus] Saxton preferred against Colonel White several charges, among which are ‘conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline’ and ‘conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.’ General Brannan, while denying the right of General Saxton to exercise any authority over the troops, has, nevertheless, ordered a general court martial to be convened, and the following officers, comprising the detail of the court, are to-day [sic] trying the case:— Brigadier General Terry, United States Volunteers; Colonel T. H. Good, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania; Colonel H. R. Guss, Ninety-seventh Pennsylvania; Colonel J. D. Rust, Eighth Maine; Colonel J. R. Hawley, Seventh Connecticut; Colonel Edward Metcalf, Third Rhode Island artillery; Lieutenant Colonel G. W. Alexander, 47th Pennsylvania; Lieutenant Colonel J. F. Twitchell, Eighth Maine; Lieutenant Colonel J. H. Bedell, Third New Hampshire; Major Gausler, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania; Major John Freese, Third Rhode Island artillery; Captain J. P. S. Gobin, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, Judge Advocate. Among the officers of the corps the act of General Saxton is generally deemed a usurpation on his part; and, inasmuch as this opinion is either to be sustained or outweighed by the Court, a good deal of interest is manifested in the trial.

White, whose regiment had just recently fought side-by-side, effectively, with the 47th Pennsylvania and other Brannan regiments in the Battle of Pocotaligo, was acquitted, according to The Historical and Genealogical Society of Indiana County, Pennsylvania, and continued to serve as an officer with the Union Army.

1863

Throughout the whole of 1863, Good and his 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were part of the U.S. Army’s District of Key West and Tortugas. During this phase of duty, they were attached to the command of Brigadier-General Daniel Woodbury.

Good became the Commanding Officer of both Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida and of the more distant Fort Jefferson—remotely located off the coast of Florida and accessible only by boat—when half of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were shipped off to garrison that Tortugas-based federal installation. (While Good used Fort Taylor as his home base, his second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander was stationed at Fort Jefferson.)

In a letter to the Sunbury American on 23 August 1863, Henry Wharton described Thanksgiving celebrations held by the regiment and residents of Key West and a yacht race the following Saturday at which participants had “an opportunity of tripping the ‘light, fantastic toe,’ to the fine music of the 47th Band, lead by that excellent musician, Prof. Bush.”

It was also noteworthy year due to the casualties incurred by disease—but even more so for the clear commitment that the men of the 47th had to preserving the Union. Many who could have returned home, their heads legitimately held high after all they had endured, instead chose to reenlist for additional three-year tours of duty when their initial service terms expired.

So effective was the service of the regiment during this time that the residents of Key West paid their respects to Colonel Good by presenting a finely crafted sword to him as a measure of their respect for the man and his subordinates. The 17 May 1918 edition of The Allentown Democrat recorded what happened to the weapon as follows:

Another gift [to the Lehigh County Historical Society] includes the sword, belt and sash presented by the citizens of Key West, in 1863, to Col. T. H. Good, commanding the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. This was given by his widow to the Allen Rifles, Company D, Fourth regiment, N. G. P. [National Guard of Pennsylvania], formerly commanded by the colonel, and is now turned over to the society by them.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake possession of Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858 following the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. Per orders issued earlier in 1864 by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, that the fort be used to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade, Colonel Tilghman Good, in consultation with his superiors, assigned Captain Richard Graeffe and a group of men from Company A to special duty, and charged them with expanding the fort and conducting raids on area cattle herds to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across Florida. Graeffe and his men subsequently turned the fort into both their base of operations and a shelter for pro-Union supporters, men and women escaping slavery, Confederate Army deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops. According to Schmidt:

Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard. Lt. Harris was directed to tow the Matchless if necessary.

Punta Rassa was probably the location where the troops disembarked, and was located on the tip of the southwest delta of the Caloosahatchee River … near what is now the mainland or eastern end of the Sanibel Causeway… Fort Myers was established further up the Caloosahatchee at a location less vulnerable to storms and hurricanes. In 1864, the Army built a long wharf and a barracks 100 feet long and 50 feet wide at Punta Rassa, and used it as an embarkation point for shipping north as many as 4400 Florida cattle….

Capt. Graeffe and company were disembarked on the evening of January 7, and Gen. Woodbury ordered the company to occupy Fort Myers on the south side of the Caloosahatchee, about 12 miles from its mouth and 150 miles from Key West. Shortly after, [a detachment of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company stationed on Useppa Island] was also ordered to proceed to Fort Myers and join the main body of Company A, the entire command under direct orders of the General who was in the area…. Gen. Woodbury returned to Key West on the Honduras prior to January 19, and the command was left in charge of Capt. Graeffe who dispatched various patrols in search of refugees for enlistment and for activities involving Confederate cattle shipments.

Company A’s muster roll provides the following account of the expedition under command of Capt. Graeffe: ‘The company left Key West Fla Jany 4. 64 enroute to Fort Meyers Coloosahatche River [sic] Fla. were joined by a detachment of the U.S. 2nd Fla Rangers at Punta Rossa Fla took possession of Fort Myers Jan 10. Captured a Rebel Indian Agent and two other men.’

Schmidt notes that Graeffe’s hand drawings show there were roughly 12 buildings “primarily situated along the river, with a log palisade protecting those portions not bounded by the Caloosahatchee; the whole in a densely wooded area and entered through an opening on the southeast protected by the river on the west near the area of the wharf, and a log blockhouse on the east.” During this phase of duty, which lasted until sometime in February of 1864, Graeffe’s A Company men subsequently added more structures and fortifications. They also captured three Confederate sympathizers at the fort, including a blockade runner and spy named Griffin and an Indian interpreter and agent named Lewis. Charged with multiple offenses against the United States, they were transported to Key West, where they were kept under guard by the Provost Marshal—Major William Gausler, third-in-command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documents the time of Richard Graeffe and the men under his Florida command this way:

A small contingent of 20 men and two officers from the Pennsylvania 47th Regiment, led by Captain Henry Crain of the 2nd Regiment of Florida, arrived at the fort on January 7, 1864. A short time later, the party was joined by another small detachment of the 47th under the command of Captain Richard A. Graeffe. Over a short period, increasing reinforcements of the fort led to increasing cattle raids throughout the region. A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.

Meanwhile, Colonel Good and his officers had begun preparing to take the members of all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reunited regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.

From 14-26 March, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry headed for Alexandria and Natchitoches, Louisiana, by way of New Iberia, Vermilionville, Opelousas, and Washington. From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron, James, and John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for service with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were then officially mustered in for duty on 22 June at Morganza. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “(Colored) Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long, grueling trek through enemy territory, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill on the night of 7 April before continuing on the next day, marching until mid-afternoon.

On 8 April, they engaged in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield), losing 60 of their friends to fierce gun and cannon fire. In the confusion, some were reported as killed in action, but apparently survived. The next day’s fighting proved to be even more intense.

On 9 April, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, former President of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the massed Union forces, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

During this engagement, the 47th Pennsylvania also recaptured a Massachusetts artillery battery that had been lost during the earlier Confederate assault. While he was mounting the 47th Pennsylvania’s colors on one of the recaptured Massachusetts caissons, Color-Sergeant Benjamin F. Walls was shot in the left shoulder. As Walls fell, Sergeant William Pyers was also shot while retrieving the American flag from Walls, thereby preventing it from falling into enemy hands.

In addition, Good nearly lost his second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, who had been severely wounded in both legs, casualties among the enlisted men were also high, and a number of soldiers were captured and held as prisoners of war by Confederate forces at Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas until released during prisoner exchanges in July, August, September, or November. Tragically, at least three members of the 47th died while in captivity, and the burial locations of others remain a mystery to this day, their bodies having been hastily interred on or between battlefields—or possibly in unmarked prison graves.

Following what some historians have called a rout by Confederates at Pleasant Hill and others have labeled a technical victory for the Union or a draw for both sides, the 47th Pennsylvanians fell back to Grand Ecore, where they remained for 11 days and engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications. They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April, arriving in Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night, after marching 45 miles. While en route, they were attacked again—this time at the rear of their brigade, but they were able to quickly end the encounter and continue on.

The next morning (23 April 1864), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on Brigadier-General Hamilton P. Bee’s Confederate Cavalry in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”). Responding to a barrage from the Confederate artillery’s 20-pound Parrott guns and raking fire from enemy troops situated near a bayou and on a bluff, Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederates busy while sending the other two brigades to find a safe spot where his Union troops could ford the Cane River. As part of the “beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Emory’s artillery.

Meanwhile, other Emory troops worked their way across the Cane River, attacked Bee’s flank, forced a Rebel retreat, and erected a series of pontoon bridges, enabling the 47th and other remaining Union troops to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. Encamping overnight before resuming their march toward Rapides Parish, the 47th Pennsylvanians finally arrived on 26 April in Alexandria, where they camped for 17 more days (through 13 May 1864).

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” for the Union officer who ordered its construction, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army across the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

During this phase of duty, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were temporarily placed under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, from 30 April through 10 May, and were assigned to help build a dam across the Red River to enable Union gunboats to more easily navigate the river’s fluctuating water levels.

The Controversy

While these battles, marches, and other military actions were all unfolding, a controversial incident roiled not only the 47th Pennsylvania’s officers’ corps, but senior levels of the Union Army’s leadership in Louisiana.

The 11 May 1864 Evening Star in Washington, D.C. gave a glimpse into the situation with the startling news that Major William H. Gausler and First Lieutenants W. H. R. Hangen and William Reese of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had been dismissed from military service “for cowardice in the actions of Sabine Cross Roads and Pleasant Hill on the 8th and 9th of April, and for having tendered their resignations while under such charges” (AGO Special Order No. 169, 6 May 1864).

The allegations against the 47th Pennsylvania’s officers would continue to trouble the hearts and minds of Colonel Good and his men for months as the situation went unresolved—despite official protests that were lodged by Good and others who condemned the allegations of cowardice against Gausler, Hangen and Reese as grossly inaccurate and unfair. The stain was finally removed from the regiment when President Abraham Lincoln stepped in. According to the History Book Club’s The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln, vol. 8 (derived from Collected Works. The Abraham Lincoln Association, 1953), President Lincoln personally reviewed and reversed the Adjutant General’s findings against Gausler. On 14 October 1864, Lincoln wrote to U.S. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton:

Please send the papers of Major Gansler [sic], by the bearer, Mr. Longnecker. A. LINCOLN

An annotation to Lincoln’s collected works explains that “Mr. Longnecker was probably Henry C. Longnecker of Allentown, Pennsylvania,” and makes clear that, although Major W. H. Gausler had indeed been dismissed for cowardice, President Lincoln disagreed with the decision, and overturned it on 17 October 1864. The notation further explains, “Although the name appears as ‘Gansler’ in Special Orders, it is ‘Gausler’ on the roster of the regiment.”

A more detailed explanation of why Colonel Good and his men were so angered by the allegations against Gausler and the others was later provided in Gausler’s 1914 obituary in The Allentown Leader:

“He was court martialed for making a superior officer apologize on his knees at the point of a gun for slurring Pennsylvania German soldiers, but was pardoned by President Lincoln.”

But, although the incident left a sour taste in the mouths of Colonel Good and his men, they did not let it deter them from their mission to preserve America’s Union and end the brutal practice of slavery across the nation. Beginning 13 May, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers moved from Simmesport to Morganza, and then to New Orleans on 20 June. On the 4th of July, Good and his men received new orders, directing them to return to the East Coast. Their departure took place in two stages.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign, Virginia

Colonel Tilghman Good and the men from Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I left Louisiana on 7 July, and steamed aboard the McClellan until reaching Virginia, where they had a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln before receiving new orders to join Major-General David Hunter’s forces. Under Hunter, this grouping of the 47th fought at Snicker’s Gap, Virginia in mid-July during the Battle of Cool Spring, and assisted, once again, in defending the nation’s capital while also helping to drive Confederate forces from Maryland.

Companies B, G and K, left behind in Louisiana under the command of F Company Captain Henry S. Harte, departed later that month, arrived on the East Coast on 28 July, and reconnected with the bulk of the regiment at Monocacy, Virginia on 2 August.

From August through November of 1864, the 47th Pennsylvanians were then attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah under legendary Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan—a phase of service during which the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would perform their greatest collective moments of valor.

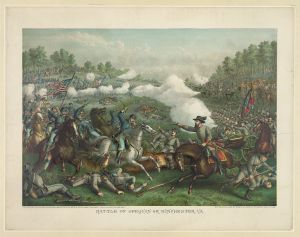

Philip Sheridan’s Union victory over Jubal Early’s Confederate troops (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Inflicting heavy casualties during the Battle of Opequan (also known as “Third Winchester”) on 19 September 1864, Sheridan’s gallant men forced a stunning retreat of Jubal Early’s Confederates—first to Fisher’s Hill (21-22 September) and then to Waynesboro, following a successful early morning flanking attack.

Their successes helped Abraham Lincoln win a second term as President, and enabled Colonel Tilghman H. Good to depart from military service as a victor when he mustered out from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers on 24 September 1864 upon expiration of his term of service. That departure was not a happy one in Good’s eyes, according to Henry Wharton of Company C, who recorded, for posterity, Good’s departing address to his men:

“Soldiers of the 47th,” — More than three years ago I assumed command as your Colonel. My relations with you as your commander have been of the most pleasing character. Your fidelity, zeal, soldierly conduct and military bearing worthy of my most hearty commendation, and to leave you, after so long a term, I trust, of mutual confidence, is indeed a painful duty. When the most of you re-enlisted under the call of the President for veterans [sic], it was my intention to have remained with you, and leave now, only, by reason of distasteful Brigade associations. My sense of honor will not permit me to remain longer with an organization in which I have suffered nothing but indignities since our connection with its [sic] as a regiment.

Return to Civilian Life

After returning home to the Lehigh Valley, Tilghman H. Good managed the American Hotel in 1865, and then pursued his interests in banking, insurance and real estate, becoming a secretary and treasurer of the Elliger Real Estate Association’s board of directors and member of the committee involved with the construction of the Adelaide Silk Mills.

Later Elected Office

On 19 March 1869, Tilghman H. Good defeated the borough’s former fire chief, George Beisel, by a vote of 1155 to 935 to become Mayor of the City of Allentown. Based on news reports of his campaign and victory, Good’s reputation as the renowned founder and commanding officer of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was clearly a factor in this election.

He was then re-elected to a second term in 1871.

Briefly turned out of office in 1873, he was elected to a third term as mayor in 1874.

Civic and Community Leadership

In 1870, Tilghman Good resumed leadership of the Allen Rifles, serving as Captain before moving up the ranks within Pennsylvania’s militia structure to Lieutenant-Colonel, 4th Regiment (1874) and Colonel (1875).

He also managed the Hotel Allen from 1875 to 1879, and then briefly opened and operated the Fountain House.

During this combined period of business management and military service, Colonel Good led Pennsylvania militiamen in quelling the railroad riots of 1877.

Death and Burial

Employed as a conductor with the Grand Central Hotel in Reading, Berks County, Pennsylvania beginning in the mid-1880s, Tilghman H. Good finally answered his last bugle call when he passed away in Reading on 18 July 1887.

His remains were brought home to the Lehigh Valley, and he was interred at the Linden Street Cemetery in Allentown in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania later that month.

Sources:

1. Basler, Roy P. Collected Works. Abraham Lincoln Association/Springfield, Illinois. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1953.

2. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, Prepared in Compliance with Acts of the Legislature, vol. 1, 1150-1190. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

3. Death Record (Tilghman H. Good), in Death Records (Reading, Berks County). Reading, Pennsylvania: Office of the Register of Wills, City of Reading, 1887.

4. “Dismissals Confirmed.” Washington, DC: Evening Star, 11 May 1864.

5. “Florida’s Role in the Civil War,” in Florida Memory. Tallahassee, Florida: State Archives of Florida.

6. Hartman, William L. The Mayors of Allentown, in Berlin’s Proceedings and Papers Read Before the Lehigh County Historical Society. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Lehigh County Historical Society, 1922.

7. Johner, Patricia E. “Paths of Glory: The Unfinished Life of Colonel Richard White,” in “Clark House News.” Indiana, Pennsylvania: The Historical and Genealogical Society of Indiana County, Pennsylvania, June 2012.

8. “Major Gausler Dead at His Phila. Home: Death Injury Received While Returning from Gettysburg Reunion.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 19 March 1914, p. 1.

9. Mathews, Alfred and Austin H. Hungerford. History of the Counties of Lehigh and Carbon. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Everts & Richards, 1884.

10. Moody, John Sheldon and Calvin Duvall Cowles, et. al. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, series 1, vol. 14. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885.

11. “News from Port Royal, S.C.: Arrival of the Steamers Bienville and Hale.” New York New York: The New York Herald, 16 December 1862.

12. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

13. “Tamiami Trail Modifications: Next Steps,” in Draft Environmental Impact Statement. Washington, D.C. and Everglades National Park, Florida: U.S. National Park Service, 2010.

14. “Trout Hall Formally Dedicated as Lehigh Co. Historical Society’s Home” (mention of Colonel Tilghman H. Good’s sword and its Key West presentation). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Democrat, 17 May 1918.

15. Wharton, Henry D. Notice of the resignation of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and transcript of his final address to the 47th Pennsylvania (dated 14 November 1864). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 26 November 1864.

You must be logged in to post a comment.