“My soul I give to god, who gave it with the blessed assurance of immortality.” – From the “Last Will & Testament of Charles Mickley dec”

If any 19th century Keystone Stater could claim to have hero’s blood flowing through his veins, it was Charles Mickley. A resident of Allentown, Pennsylvania’s Second Ward at the dawn of America’s greatest national crisis, Charles Mickley was descended from the Rev. Louis Michelet, a Huguenot refugee who fled from Metz in Alsace Lorraine to Zweibrücken in Germany’s Rhineland-Palatinate to escape the religious persecution of King Louis XIV of France. There, Rev. Michelet served his fellow refugees and community as a practicing pastor in the Protestant faith.

In 1733, the Rev. Michelet’s son, Jean Jacques Michelet, sailed to America aboard the ship, Hope – also in search of religious freedom, as did many fellow members of the German Palatinate. Following his arrival in Philadelphia, Jean Jacques Michelet lived with relatives in Oley, Berks County, Pennsylvania for several years before relocating to Whitehall Township, Northampton County (in what is now North Whitehall, Lehigh County). There, he married Elizabeth Barbara Burkhalter, and raised a family, including son, John Jacob Mickley (1737-1808).

Motto: “War, the Chase and Liberty.” Coat of Arms, Family of Michelet, free city of Metz, German empire. (Professor Dr. C. F. Michelet’s book of Vienna heraldry; provided to Minnie F. Mickley, 1883, public domain).

Sometime afterward, their surname was Anglicized from “Michelet” to “Mickley.” Their land, initially heavily forested, was later developed into farmland and ultimately renamed, becoming the Lehigh County village of “Mickleys.”

This son of religious refugees – John Jacob Mickley – later began his own family, choosing for his place of residence an area of South Whitehall near the village of Hokendauqua. By the age of 39, John Jacob Mickley had become famous in his own right. One of the American Revolutionary War Patriots who helped to prevent British General William Howe’s troops from capturing the Liberty Bell, he used his own farm’s horses and wagon to help the Continental Army spirit the bell away from Philadelphia in September 1777 and into the hands of the Rev. Abraham Blumer, pastor of Allentown’s Zion Church, where it remained safe until returned to its place of honor in Philadelphia in 1778.

Nearly two centuries after his great-grandfather helped to save one of America’s most treasured icons of freedom, Charles Mickley would also go on to serve his nation with courage and distinction at the age of 39 before achieving an unwished-for fame of his own.

Formative Years of Charles Mickley

Born near the village of Mickleys in Whitehall Township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania on 27 January 1823, Charles Mickley was a son of Joseph Mickley (1800-1832) and Catharine (Miller) Mickley (1803-1888). His mother, Catharine, was a native of Whitehall Township in Northampton County, Pennsylvania; his father, Joseph, was a son of Lehigh County native, Peter Mickley (1772-1861), and Whitehall Township native, Salome (Biery) Mickley (1773-1806).

* Note: Although some sources give Charles Mickley’s date of birth as 1821 or 1823, military records and the newspaper obituary published immediately after his death indicate that he was born in 1823.

Following his schooling and spiritual development in Whitehall Township, Charles Mickley secured employment as a clerk at Trexler’s in Longswamp Township. Sometime during the mid-1840s, he wed Elizabeth Heimbach (1828-1881). A Pennsylvania native, she was born on 31 May 1828.

On 6 February 1846, Charles and Eliza welcomed daughter Sarah Ann Mickley (1846-1920) to the world. Two years later, they greeted the birth of a New Year with the arrival of their son, Winfield Scott Mickley (1848-1871), who was born on 1 January 1848.

Paradise (above) and Rough and Ready iron furnaces (c. 1935, The Swigart-Shedd Family Collection on Pennsylvania Iron Furnaces, Special Collections Library, Pennsylvania State University).

Sometime during the mid to latter part of this decade Charles Mickley entered Pennsylvania’s growing iron production industry, becoming the superintendent of the Paradise Furnace in Todd Township, Huntingdon County, Pennsylvania. Known also as the Mary Anne Furnace and owned by Trexler & Company, this iron furnace smelted local ore into domestic utensils and kitchen stoves. Out of blast from 1850 until 1865, its owners subsequently resumed operations for another three years. Today, its ruins may still be seen at Huntingdon County’s Trough Creek State Park.

By 1850, Charles Mickley was a 29-year-old superintendent of the Rough and Ready Furnace in Hopewell Township. Owned by S. T. Watson & Co. and located in Coffee Run near the Huntingdon & Broad Top Railroad’s Hummel Station, five miles west of the Paradise Furnace and 20 miles south of Hungtingdon, the Rough and Ready operation was a cold-blast charcoal furnace which produced 20 tons of iron per week until it too was idled in 1856.

During his tenure with the Rough and Ready Furnace, Charles Mickley continued to make his home in Huntingdon County’s Todd Township with his wife, Eliza, and their children, Sarah and Winfield. Their son, William Deshler Mickley (1850-1932) arrived at the Mickley family home on 8 July 1850. Son Charles Henry Mickley (1852-1911) was born in Huntingdon County on 19 October 1852.

During his tenure with the Rough and Ready Furnace, Charles Mickley continued to make his home in Huntingdon County’s Todd Township with his wife, Eliza, and their children, Sarah and Winfield. Their son, William Deshler Mickley (1850-1932) arrived at the Mickley family home on 8 July 1850. Son Charles Henry Mickley (1852-1911) was born in Huntingdon County on 19 October 1852.

On 14 October 1854, Charles and Eliza Mickley welcomed son Thomas Franklin Mickley (1854-1931) to their Huntington County home.

Sometime around 1857, he and his wife returned home to Lehigh County to begin life anew. Notices posted by Mickley in 1857 and 1858 editions of Der Lecha Patriot, one of the region’s German language newspapers, announced that he had entered into partnership agreements with Augustus Ruhe, Joseph Weaver and Ephraim Grim to revitalize the operations of an old, large grist mill, and had also worked out an agreement for water with the city’s water company. Adding that he and his partners were willing to give reasonable terms to all who still owed payment to the old mill if they would promptly settle their outstanding accounts, he also advised future customers of his companies – Ruhe & Mickley (and later Weaver, Mickley & Co.) – that he and his partners would be prepared, after 1 April 1858, to begin grinding fruit, corn, wheat and oats, and would charge the cheapest prices available to consumers while offering “the highest market prices” to those bringing their corn for milling.

On 13 September 1859, Charles and Eliza Mickley greeted the birth of their youngest son, John Heimbach Mickley (1859-1865) with joy.

By 1860, Charles Mickley was thriving professionally. Employed as a “Master Miller” in Lehigh County, according to the federal census for that year, his real estate holdings were valued at $20,750 with his personal estate valued at $11,500. He resided in Allentown, Pennsylvania’s Second Ward with his wife, Eliza, and their children: Sarah Ann (shown as “Mary” on the federal census), Winfield Scott, William Deshler, Charles Henry, Thomas Franklin (1854-1931), Caroline Heimbach (“Carrie”), and John Heimbach Mickley.

Civil War Military Service

Normally tradition-rich times of boundless joy for German families across Pennsylvania, Christmas 1860 and the dawning New Yearof 1861 were marred by worry for the Mickley family and their friends as America’s southern states tipped into their domino fall of secession: South Carolina (December 1860), Mississippi (9 January 1861), Florida and Alabama (10-11 January 1861), Georgia (19 January 1861), Louisiana (26 January 1861) and Texas (1 February 1861).

As relations worsened betwen America’s North and South, neighbors spread word of the latest developments at local stores and churches. By late April 1861, members of local militia units were marching off to perform their Three Months’ Service in defense of the nation’s capital following the fall of Fort Sumter to Confederate forces. Those who remained behind began planning their towns’ next moves while earnestly hoping that the North’s swift response would quickly resolve the discord.

One such planner was Charles Mickley, who took an active part in recruiting the men who would form part of a new regiment being raised by Tilghman H. Good – the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. During the Summer of 1861, Mickley helped to convince nearly a hundred of his fellow Allentown residents to sign up for three-year terms of military service before personally mustering in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County as a Corporal with the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on 18 September 1861.

Honoring both his success as a recruiter and his proven abilities as a leader of men in the iron and mill industries, his superiors promptly commissioned him as a Captain, and gave him command of his recruits who had mustered in that same day as Company G of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Also on that day, Charles A. Henry and John J. Goebel were made Captain Mickley’s senior staff, serving respectively as Company G’s 2nd and 1st Lieutenants.

Following a brief light infantry training period at Camp Curtin, Captain Mickley and his company were sent by train with the 47th Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C., where they were stationed at “Camp Kalorama” on Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, about two miles from the White House, beginning 21 September. Henry Wharton, a Musician from C Company, penned the following update on 22 September for the Sunbury American newspaper:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

As a unit of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Company G became part of the federal service when the regiment officially mustered into the U.S. Army on 24 September. On September 27, a rainy, drill-free day which permitted many of the men to read or write letters home, the 47th Pennsylvania was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of W.F. Smith’s Army of the Potomac. That afternoon, they marched to the Potomac River’s eastern side and, after arriving at Camp Lyon, Maryland, marched double-quick over a chain bridge before heading on toward Falls Church, Virginia.

Arriving at Camp Advance at dusk, they pitched their tents in a deep ravine about two miles from the bridge they had just crossed, near a new federal military facility under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). Armed with Mississippi rifles supplied by the Keystone State, they would join with their regiment, the 3rd Brigade and Smith’s Army of the Potomac in defending the nation’s capital until January when the 47th Pennsylvania would be ordered to duty in the Deep South.

Sometime during this month, according to Lewis Schmidt, author of the definitive history of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: “Pvt. Reuben Wetzel, a 46 year old cook in Capt. Mickley’s Company G,” climbed up on a horse that was pulling his company’s wagon while his regiment was engaged in a march from Fort Ethan Allen to Camp Griffin (both in Virginia). When the regiment arrived at a deep ditch, “the horses lost their footing and the wagon overturned and plunged into the ditch, with ‘the old man, wagon, and horses, under everything.’” Based on his review of military records, Schmidt believed that Pvt. Jacob H. Bowman (aged 35), a former Allentown miller who was Company G’s designated wagon master, was likely the driver at the time of Private Wetzel’s accident. Both men were serving under Captain Charles Mickley at the time of this incident.

Although alive when pulled from the wreckage, Pvt. Wetzel fractured a tibia, a serious injury even today. Just five weeks later, he succumbed to complications (on 17 November 1861) while being treated for the fracture and resulting amputation of his leg at the Union Hotel General Hospital in Georgetown, Washington, D.C. He was interred at the Military Asylum Cemetery (now known as the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home National Cemetery).

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads after having been ordered with the 3rd Brigade to Camp Griffin. In a letter home around this time, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin (the leader of C Company who would be promoted in 1864 to head the entire 47th Regiment) reported that companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops.

On Friday morning, 22 October 1861, the 47th engaged in a Divisional Review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward – and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained brand new Springfield rifles, and ordered that they be distributed to every member of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Sadly, Captain Mickley’s Company G would suffer another early casualty that fall when it lost Private William Young. Treated for heart problems by the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Surgeon, Elisha Baily, M.D., Private Young was released from G Company at Camp Griffin, Virginia on a Surgeon’s Certificate of Disability on 23 November 1861, but died before he could make it back home, passing away from valvular heart disease in Washington, D.C. the following day (on 24 November 1861). Like Private Wetzel, he was also interred at the Military Asylum Cemetery in Washington, D.C.

1862

The dawn of a New Year brought more changes to Captain Mickley’s G Company. Privates Solomon Becker and Nelson Coffin of Company G were promoted to the rank of Corporal on New Year’s Day 1862; less than two weeks later, on 13 January, 1st Sergeant G. W. Huntzberger was promoted to the rank of 2nd Lieutenant. On 18 January, Private Hiram Brobst was discharged on a Surgeon’s Certificate.

Next ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862, marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church. Sent by rail to Alexandria, they then sailed the Potomac via the steamship City of Richmond to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped before they were marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C. The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped railcars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

According to Schmidt and letters home from members of the regiment, those preparations ceased on Monday, 27 January, at 10 a.m. when:

The regiment was formed and instructed by Lt. Col. Alexander ‘that we were about drumming out a member who had behaved himself unlike a soldier.’ …. The prisoner, Pvt. James C. Robinson of Company I, was a 36 year old miner from Allentown who had been ‘disgracefully discharged’ by order of the War Department. Pvt. Robinson was marched out with martial music playing and a guard of nine men, two men on each side and five behind him at charge bayonets. The music then struck up with ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the procession was marched up and down in front of the regiment, and Pvt. Robinson was marched out of the yard.

Reloading then resumed. By that afternoon, when the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers commenced boarding the Oriental, they were ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamers. The officers boarded last and, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, the Oriental steamed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. They were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

In early February 1862, Company G and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Key West, where they were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor. Drilling daily in heavy artillery tactics and other military strategies, they also felled trees, build new roads and helped to strengthen the facility’s fortifications.

On 3 March, G Company’s Sergeant Charles A. Hackman was promoted to the rank of 1st Sergeant. The following day, Privates Daniel Ansbach, Joseph Fisher, John Meisenheimer and John Schimpf, Sr. were discharged on Surgeons’ Certificates. On 1 April 1862, Corporal D. K. Deifenderfer was promoted to the rank of Sergeant. On 18 May 1862, Private Edmund G. Scholl died at Fort Taylor.

From mid-June through July, the 47th was ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina where the men made camp before being housed in the Department of the South’s Beaufort District. Picket duties north of the 3rd Brigade’s camp were commonly rotated among the regiments present there at the time, putting soldiers at increased risk from sniper fire. According to historian Samuel P. Bates, the men of the 47th “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing.”

That Summer, Private John A. Ulig received a Surgeon’s Certificate discharge on 12 August 1862. On 10 September 1862, Private Henry Zeppenfeldt died from typhoid fever at the Union Army’s General Hospital No. 2 at Beaufort, South Carolina.

Sent on a return expedition to Florida, Company G saw its first truly intense moments when it participated with the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff from 1 to 3 October. Led by Brigadier-General Brannan, a 1,500-plus Union force disembarked at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek from troop carriers guarded by Union gunboats.

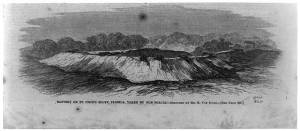

J.H. Schell’s 1862 illustration showing the earthen works which surrounded the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff along the Saint John’s River in Florida (public domain).

Taking point, the 47th led the 3rd Brigade through 25 miles of dense, pine forested swamps populated with deadly snakes and alligators. By the time the expedition ended, the brigade had forced the Confederate Army to abandon its artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, and had paved the way for the Union to occupy the town of Jacksonville, Florida.

Then, Companies E and K of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were detached on special duty. Ordered to sail up the Saint John’s River with other regiments which had just been engaged in capturing Saint John’s Bluff, these 47th Pennsylvanians helped to capture the Gov. Milton, a Confederate steamer which had supplied not only the batteries atop the bluff, but Confederate forces throughout the region.

In Peril at Pocotaligo

Pocotaligo Depot, Charleston & Savannah Railroad, South Carolina as sketched by Theodore R. Davis for Harper’s Weekly, 25 February 1865 edition (public domain).

From 21-23 October, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th engaged Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point, the men of the 47th were placed on point once again, but they and the 3rd Brigade were less fortunate this time.

Harried by snipers en route to the Pocotaligo Bridge, they met resistance from an entrenched, heavily fortified Confederate battery which opened fire on the Union troops as they entered an open cotton field. Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered artillery and infantry fire from the surrounding forests.

The Union soldiers grappled with the Confederates where they found them, pursuing the Rebels for four miles as they retreated to the bridge. There, the 47th relieved the 7th Connecticut. But the enemy was just too well armed. After two hours of intense fighting in an attempt to take the ravine and bridge, depleted ammunition forced the 47th to withdraw to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th were significant. Two officers and 18 enlisted men died, including Privates Benjamin Diehl, James Knappenberger, John Kuhns (alternate spelling: Kuntz), and George Reber, who had served with Captain Mickley’s G Company. Privates Knappenberger and Kuhns were killed in action during the 47th’s early engagement at the Frampton Plantation; Thorntown, Pennsylvania resident George Reber sustained a fatal gunshot wound to his head.

Another two officers and 114 enlisted were wounded in action, including G Company’s Private Franklin Oland, who died from his wounds at the Union Army’s general hospital at Hilton Head, South Carolina on 30 October, and Private John Heil, who sustained a gunshot wound (“Vulnus Sclopet”) and succumbed to his own battle wound-related complications at Hilton Head on 2 November 1862.

Jacob Henry Scheetz, M.D., Assistant Regimental Surgeon, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, who subsequently cared for the fallen at the U.S. Army’s General Hospital at Hilton Head, also documented another sad truth. One of the officers who had been cut down that day was G Company’s Captain Charles Mickley. A notation by Dr. Scheetz in the U.S. Army’s Register of Deaths of Volunteers certified that Captain Mickley had been “killed in action” at “Frampton SC” (the Frampton Plantation).

The challenging environment of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad was illustrated by Harper’s Weekly in 1865.

A 1987 article by Frank Whelan for Allentown’s Morning Call newspaper provides more detail regarding what happened:

It was a venture designed to cut a railroad linking Charleston and Savannah, Ga. But poor planning by the overall Union commander, a Gen. Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel, seemed to doom it to failure from the start. The officers in charge of the brigades expected to meet 10,000 armed Southern troops when they landed.

Yet the men of the 47th knew none of this. Like any men before a battle, they got ready for it in various ways. Young Capt. Charles Mickley of G Company picked up a pen to write a Lehigh Valley friend the night before the assault.

He enclosed a check for $600, the pay he had received that day. He asked his friend to set it aside in a savings bank for his wife.

After taking care of that bit of business, Mickley expressed his apprehension. ‘Today at one o’clock our Reg. will embark on the Steamer Ben Deford to go on an Expedition which our Reg is to take part in. But where we are agoing to, we are as yet kept in the dark about . . . I must beg pardon by putting you to so much trouble to attend to my affairs but as you are well aware when one is absent from home he leaves his matters to men as one has confidence in. If you were a young man I would say go and fight for your country. But as you are past the Meridian of life to do soldiering; there must be Patriots at home as well as in the field. If such were not the case how should we get along in the field. CM.’

The next morning Capt. Mickley and his men in the 47th were no longer in the dark. Outside of a farm called Frampton Plantation, near Pocotaligo, he found himself face to face with hot Rebel fire. As shell and canister and grapeshot raked the line, the bold Mickley charged forward into what commanding officer Tilghman Good called ‘a perfect matting of vines and brush . . . almost impossible to get through.’ Less than 24 hours after he penned his letter home, Charles Mickley was lying dead on the first battlefield of his life. His new home would be Union Cemetery.

Union Army map of the Pocotaligo-Coosawhatchie Expedition, 21-23 October 1862 (public domain; click to enlarge).

In his report on the engagement, made from headquarters at Beaufort, South Carolina on 24 October 1862, Colonel Tilghman H. Good provided details of the 10th Army’s ill-fated engagement:

SIR: I have the honor to submit the following report of the part taken by the Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers in the action of October 22:

Eight companies, comprising 480 men, embarked on the steamship Ben De Ford, and two companies, of 120 men, on the Marblehead, at 2 p.m. October 21. With this force I arrived at Mackays Landing before daylight the following morning. At daylight I was ordered to disembark my regiment and move forward across the first causeway and take a position, and there await the arrival of the other forces. The two companies of my regiment on board of the Marblehead had not yet arrived, consequently I had but eight companies of my regiment with me at this juncture.

At 12 m. I was ordered to take the advance with four companies, one of the Forty-seventh and one of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania Volunteers, and two of the Sixth Connecticut, and to deploy two of them as skirmishers and move forward. After moving forward about 2 miles I discerned some 30 or 40 of the enemys [sic] cavalry ahead, but they fled as we advanced. About 2 miles farther on I discovered two pieces of artillery and some cavalry, occupying a position about three-quarters of a mile ahead in the road. I immediately called for a regiment, but seeing that the position was not a strong one I made a charge with the skirmishing line. The enemy, after firing a few rounds of shell, fled. I followed up as rapidly as possible to within about 1 mile of Frampton Creek. In front of this stream is a strip of woods about 500 yards wide, and in front of the woods a marsh of about 200 yards, with a small stream running through it parallel with the woods. A causeway also extends across the swamp, to the right of which the swamp is impassable. Here the enemy opened a terrible fire of shell from the rear, of the woods. I again called for a regiment, and my regiment came forward very promptly. I immediately deployed in line of battle and charged forward to the woods, three companies on the right and the other five on the left of the road. I moved forward in quick-time, and when within about 500 yards of the woods the enemy opened a galling fire of infantry from it. I ordered double-quick and raised a cheer, and with a grand yell the officers and men moved forward in splendid order and glorious determination, driving the enemy from this position.

On reaching the woods I halted and reorganized my line. The three companies on the right of the road (in consequence of not being able to get through the marsh) did not reach the woods, and were moved by Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander by the flank on the causeway. During this time a terrible fire of grape and canister was opened by the enemy through the woods, hence I did not wait for the three companies, but immediately charged with the five at hand directly through the woods; but in consequence of the denseness of the woods, which was a perfect matting of vines and brush, it was almost impossible to get through, but by dint of untiring assiduity the men worked their way through nobly. At this point I was called out of the woods by Lieutenant Bacon, aide-de-camp, who gave the order, ‘The general wants you to charge through the woods.’ I replied that I was then charging, and that the men were working their way through as fast as possible. Just then I saw the two companies of my regiment which embarked on the Marblehead coming up to one of the companies that was unable to get through the swamp on the right. I went out to meet them, hastening them forward, with a view of re-enforcing the five already engaged on the left of the road in the woods; but the latter having worked their way successfully through and driven the enemy from his position, I moved the two companies up the road through the woods until I came up with the advance. The two companies on the right side of the road, under Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander had also worked their way up through the woods and opened fire on the retreating enemy. At this point I halted and reorganized my regiment, by forming close column by companies. I then detailed Lieutenant Minnich, of Company B, and Lieutenant Breneman, of Company H, with a squad of men, to collect the killed and wounded. They promptly and faithfully attended to this important duty, deserving much praise for the efficiency and coolness they displayed during the fight and in the discharge of this humane and worthy trust.

The casualties in this engagement were 96. Captain Junker of Company K; Captain Mickley, of Company [sic] I, and Lieutenant Geety, of Company H, fell mortally wounded while gallantly leading their respective companies on.

I cannot speak too highly of the conduct of both officers and men. They all performed deeds of valor, and rushed forward to duty and danger with a spirit and energy worthy of veterans…

As Good continued, he made clear that despite men falling around them, the 47th continued to fight on:

The rear forces coming up passed my regiment and pursued the enemy. When I had my regiment again placed in order, and hearing the boom of cannon, I immediately followed up, and, upon reaching the scene of action, I was ordered to deploy my regiment on the right side of the wood, move forward along the edge of it, and relieve the Seventh Connecticut Regiment. This I promptly obeyed. The position here occupied by the enemy was on the opposite side of the Pocotaligo Creek, with a marsh on either side of it, and about 800 yards distant from the opposite wood, where the enemy had thrown up rifle pits all along its edge.

On my arrival the enemy had ceased firing; but after the lapse of a few minutes they commenced to cheer and hurrah for the Twenty-sixth South Carolina. We distinctly saw this regiment come up in double-quick and the men rapidly jumping into the pits. We immediately opened fire upon them with terrible effect, and saw their men thinning by scores. In return they opened a galling fire upon us. I ordered the men under cover and to keep up the fire. During this time our forces commenced to retire. I kept my position until all our forces were on the march, and then gave one volley and retired by flank in the road at double-quick about 1,000 yards in the rear of the Seventh Connecticut. This regiment was formed about 1,000 yards in the rear of my former position. We jointly formed the rear guard of our forces and alternately retired in the above manner.

My casualties here amounted to 15 men.

We arrived at Frampton (our first battle ground) at 8 p.m. Here my regiment was relieved from further rear-guard duty by the Fourth New Hampshire Regiment. This gave me the desired opportunity to carry my dead and wounded from the field and convey them back to the landing. I arrived at the above place at 3 o’clock the following morning.

While Colonel Good was working on those reports, his subordinates were figuring out how to honor one of Captain Mickley’s final requests – to return his remains to northern soil – through southern lines – to his loved ones for a proper funeral and burial.

The Last Hours of Captain Mickley

Der Lecha Patriot reported that Captain Charles Mickley had suffered a fatal head wound during the Battle of Pocotaligo on 22 October 1862 on “the railway between Charleston, South Carolina and Savannah, Georgia.” His “remains were brought immediately after his death to his home in Allentown.”

Peter Wolf, sutler for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, was the man who arranged to have Captain Mickley’s remains carried north. The funeral, officiated by Rev. Derr and Rev. Brobst at Allentown’s Reformation Church, was widely attended by a “suffering entourage,” according to local newspapers, and included Mickley’s widow, Elizabeth, and their young children. Captain Charles Mickley was then laid to rest at the Union-West End Cemetery in Allentown.

As he wrote his Last Will & Testament (penned shortly before the Battle of Pocotaligo in October 1862 and proven 14 November 1862), Captain Mickley’s thoughts were of his God and his family:

In the name of God Amen. I Charles Mickley of Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, now in the Army of the United States stationed at Beaufort, South Carolina, being of sound mind and memory and good understanding, considering the uncertainty of this transiting would do make and declare this to be my last will and Testament in manner as follows to wit: First, My soul I give to god who gave it, with the blessed assurance of a blissful immortality. Second, It is my wish that immediately after my decease my body may be intered [sic] in a decent and respectful manner, without making any ostentations or display. Third, My funeral expenses to be paid (to be first paid) by my Executor herein after named, out of the first funds he may get in hand, the remainder of my Real & Personal property, wich [sic] it has pleased God to bless me with I devise in maner [sic] as follows, to wit: Item, I give and bequeath unto my beloved wife Eliza all my house and kitchen furniture, beddings, and all provisions on hand, to be absolutely hers. Item, that as long as she remains my Widow. She shall have all the income of my Real and Personal Estate, – after deducting the necessary expenses, until our youngest son John arrives at the age of eighteen years, then my Real Estate property is to be appraised and disposed off [sic] by my Executor, the proceeds thereof to be divided as follows: One third to be set aside and put on interest for the use of my Widow, the interest to be payable semi annually [sic] and paid over to my Widow by my Executor, the remainder two thirds to be equally divided, share and share alike among my seven lawful children. Vis: Sarah Ann Mickley, Winfield Scott Mickley, William Deshler Mickley, Charles Henry Mickley, Thomas Franklin Mickley, Caroline Heimbach Mickley and John Heimbach Mickley. Item, All my personal effects, such as money on hand or money on interest shall be applied to pay my debts, if any money remains over, He shall add it to other money that he may receive from the income of my Estate and may apply it so hereafter directed. Item, The twenty five shares of Stock that I hold in the Allentown Rolling Mill shall not be disposed off [sic] by my Executor until par value can be had for it, and than [sic] only at the option of my Executor, unless he should consider a benefit to my Estate to take less than par value, He will be allowed to sell all said Rolling Mill stock, and at such a price as he may consider fair and just. Item, All my investment in stocks in the Huntingdon and Broad Top Mountain Rail Road and Coal Company, amounting to nearly seven thousand dollars shall not be disposed off [sic] by my Executor for less than forty dollars per share. Should the Company be able to pay six per cent dividends, my Executor may at his option (if he thinks it is for the benefit of my Estate) keep the stock until [sic] my youngest son John shall arrive at the age of eighteen years, than [sic] the stock shall be equally divided amongst my lawfull [sic] children aforesaid. Item, But should my Widow inter-marry again before my youngest son arrives at the age of eighteen years, my Executor shall immediately after her marriage proceed to dispose of all my Real Estate, and from said proceeds sett [sic] apart One Thousand Dollars to be put on interest and said interest to be paid over to my Widow by my Executor annually during her lifetime. The remainder of said proceeds to be equally divided among my seven lawful children aforesaid. Item, That as long as my wife remains my Widow, she shall also have all the net [sic] income of my Rail Road and Rolling Mill stock, but when our youngest son John arrives at the age of eighteen years, then she shall draw only one third of the income of said stocks. The remaining two thirds to be equally divided amongst my seven lawfull [sic] children aforesaid. After marriage, she forfeits this claim. Item, That as long as my Widow draws all the income of my Real and Personal Estate, she shall maintain raise and educate our children from the income of my Estate, but as soon as she ceases to draw all the income of my estate, this charge and responsibility shall cease. Item, the fifteen acres of land that I hold situated in Salsbury [Salsbring? Salsburg?] Township, Lehigh County, my Executor is directed to sell provided he can get Three thousand five hundred dollars for said tract of Land, bt until [sic] such price can be got, he will either rent it or farm it to the best advantage of my Estate. Item, It is my desire that from all money arising from my Estate or effects my Executor shall invest in seven per cent Bonds of the Allentown Water Company if he thinks it safe and prudent to invest in said Bonds, the interest of wich [sic] are payable semi annually ]sic]. Item, as long as my wife remains my Widow she shall have the sole occupancy and possession of the House she now occupies, or until my youngest son John shall arrive at the age of eighteen. In either case my Executor shall take possession of the house & lot, and make such disposition wich [sic] he considers best to the advantage of my Estate, and the proceeds to be equally divided amongst my lawful children aforesaid. And lastly I appoint Franklin P. Mickley of North Whitehall Township Lehigh County Penna. to be my Executor to carry out the provision of this my last Will and Testatment. Done at Beaufort, South Carolina this twenty fourth day of September in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty two. Charles Mickley

Sadly, Captain Mickley’s hopes and dreams for his youngest son, John, would go unrealized. Just over two years after his father was killed in battle, John Heimbach Mickley died in Allentown on 11 January 1865. Like his father before him, he was laid to rest at the Union-West End Cemetery.

To learn what happened to the remaining members of Charles Mickley’s family, read Part II of this family sketch, The Mickleys of Lehigh County: A Civil War-Era Family Mourns and Endures.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5. Harrisburg, 1869.

2. Baptismal, Marriage, Death and Burial Records of the Mickley Family, in Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records. Philadelphia: Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

3. Civil War Muster Rolls, in Records of the Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs (Record Group 19, Series 19.11). Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

4. Civil War Veterans Card File. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania State Archives.

5. Col. W. D. Mickley Dies in Allentown, in Harrisburg Telegraph. Harrisburg: 31 March 1932.

6. Death Certificates of the Mickley Family. Harrisburg: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Bureau of Health, Department of Vital Statistics.

7. Death from Diphtheria (Charlie Mickley) and Four Deaths in One Family from Diphtheria, in The Allentown Democrat. Allentown: 23 October 1889 and 30 October 1889.

8. Death of Charles H. Mickley: Veteran Driver of America Chemical Co. Passes Away, in The Allentown Leader. Allentown: 19 January 1911.

9. Der Lecha Patriot. Allentown: Various Dates:

- Un Die Bauern!, in Der Lecha Patriot. Allentown: 11 March 1857.

- Gesellschafts – Nachricht, in Der Lecha Patriot. Allentown: 31 March 1858.

- Gesellschafts – Unflösung, in Der Lecha Patriot. Allentown: 7 April 1858.

10. Last Will & Testament of Charles Mickley dec, in Probate Records. Lehigh County: Register of Wills, 14 November 1862.

11. Lesley, J. P. The Iron Manufacturer’s Guide to the Furnaces, Forges and Rolling Mills of the United States with Discussions of Iron as a Chemical Element, an American Ore, and a Manufactured Article, in Commerce and in History. New York: John Wiley, Publisher, 1859.

12. Mickley, Minnie F. The Genealogy of the Mickley Family in America Together with a Brief Genealogical Record of the Michelet Family of Metz, and Some Interesting and Valuable Correspondence, Biographical Sketches, Obituaries and Historical Memorabilia. Newark: Advertiser Printing House, 1893.

13. Roberts, Charles Rhoads and Rev. John Baer Stoudt, et. al. History of Lehigh County Pennsylvania and a Genealogical and Biographical Record of Its Families, Vol. III. Allentown: Lehigh Valley Publishing Company, 1914.

14. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown: Self-published, 1986.

15. U.S. Census. Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania: 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920 1930.

16. William D. Mickley, in He’s Still a Major: Mickley of Allentown Reelected by Fourth Regiment Officers, in The Allentown Leader. Allentown: 20 June 1901.

17. William D. Mickley, in Major Mickley Hurt in Fall, in The Allentown Democrat. Allentown: 20 January 1915.

18. William D. Mickley, in National Guard: Recent Commissions That Have Been Issued from Headquarters, in Daily Telegraph. Harrisburg: 1 August 1884.

19. William D. Mickley, in State Revenue from Lehigh County (Auditor General’s 1892 report recap), in The Allentown Democrat. Allentown: 29 March 1893.

You must be logged in to post a comment.