Alternate Given Name: David. Alternate Spellings of Surname: Bataglia, Battaghlia, Battaglia.

Born in Switzerland in 1829, Daniel Battaglia was a 34-year-old barkeeper and resident of Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania at the outset of the American Civil War. He enrolled for military service at Easton on 15 September 1861, and mustered in for duty the following day as a Private with Company A, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry at Camp Curtin, Harrisburg, Dauphin County, where he received basic training in light infantry tactics.

Company A was led by Richard A. Graeffe, who had performed his Three Month’s Service with Company G, 9th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry prior to receiving his officer’s commission with the 47th Pennsylvania.

According to A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers, authored by Lewis Schmidt, “The Easton Express reported on August 14 that … 33 year old Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, a merchant from Easton who would command Company A of the 47th, was recruiting at Glantz’s’ in Easton,” and that is likely the place where Daniel Battaglia was recruited and possibly also the place where he may have been employed.

* Note: The Glanz saloon in Easton was operated by Charles Frederick William Glanz, an 1845 emigrant from Germany who became captain of the Northampton County militia unit known as the “Easton Jaegers” in the late 1850s. Glanz, who had gone into the brewery business with W. Kuebler in 1852, also became one of the commanding officers of the 9th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the regiment’s Three Months’ Service and then returned home to raise the men needed to form the 153rd Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, for which he was commissioned a Colonel, and became that regiment’s commanding officer.

At the time of his enlistment, military records described the newly minted Private Battaglia as being 5’9” tall with sandy hair, dark eyes and a sallow complexion.

Fall of 1861

Following training, Daniel Battaglia and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent by train to Washington, D.C., where they were stationed about two miles from the White House at “Camp Kalorama” on Kalorama Heights beginning on 21 September 1861. The next day, C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton penned the following update for the Sunbury American newspaper:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

The entire regiment was then mustered into the U.S. Army with great fanfare on 24 September of that same year. On 27 September, the 47th Pennsylvania was assigned (with the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments) to Brigadier-General Isaac Stevens’ 3rd Brigade. By early afternoon, Private Daniel Battaglia was marching behind the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental band (with his Mississippi rifle, supplied by the Keystone State) en route to the eastern side of the Potomac River and Camp Lyon, Maryland, which was situated near a chain bridge. By 5 p.m., the 47th and 46th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent double-quick across that bridge into Rebel territory. Arriving at Camp Advance about two miles from the Chain Bridge, they made camp at dusk in a deep ravine near Fort Ethan Allen. They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were encamped near General W. F. Smith’s headquarters, and were now part of the larger Army of the Potomac, assigned to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January when the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” for the large chestnut tree located within their lodging’s boundaries. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly 10 miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads after having been ordered with the 3rd Brigade to Camp Griffin. In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday, 22 October, the 47th engaged in a Divisional Review, described by Schmidt as “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” Less than a month later, in his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward—and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brannan obtained new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

1862

Next ordered to move from their Virginia encampment back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862, marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church. Sent by rail to Alexandria, they then sailed the Potomac via the steamship City of Richmond to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped before they were marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C. The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

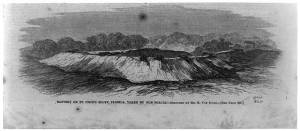

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Traveling south on the steamer Oriental from 27 January to February 1862, Private Daniel Battaglia and the men of the 47th sailed to Key West, Florida. Upon their arrival, they were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor and protect residents of the area who remained loyal to the Union. Drilling daily in heavy artillery tactics, they also strengthened the federal installation’s fortifications. On 14 February, the regiment made its presence known to area residents via a parade through the city’s streets. That weekend, a number of men from the regiment mingled with Key West residents as they attended services at local churches.

Not surprisingly, a fair number of the 47th who lost their lives during the Civil War were claimed not by rifle or cannon fire, but by dysentery and other diseases spread by troops suddenly placed in close military quarters, as well as by typhoid fever and other tropical diseases which plagued the inhabitants of Florida and its neighboring states. Fourth Sergeant Andrew Bellis of Company A was one of those so felled. Increasingly unable to turn out for duty due to repeated bouts of illness, he was reduced in rank to Private and finally died on 23 February 1862.

From mid-June through July, the 47th Pennsylvania was ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina where the men made camp before being housed in the Department of the South’s Beaufort District. Picket duties north of the 3rd Brigade’s main staging area were commonly rotated among the various regiments stationed there during this time, putting soldiers at risk from sniper fire. According to historian, Samuel P. Bates, the men of the 47th “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan” for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing.”

On 30 September 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry headed back to Florida, where it engaged with other Union infantry regiments and the Union Navy in capturing Saint John’s Bluff from 1 to 3 October. Led by Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, the 1,500-plus Union force disembarked from troop carriers with gunboat support at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek, Florida. The expedition would take Private Daniel Battaglia and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians deeper into Confederate territory than they could ever possibly have imagined.

J.H. Schell’s 1862 illustration showing the earthen works which surrounded the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff along the Saint John’s River in Florida (public domain).

Assigned to point, the 47th led the brigade through 25 miles of heavily forested swampland teeming with poisonous snakes, alligators, disease-carrying insects and Rebel troops. Skirmishing their way through, the brigade forced the Confederate Army to abandon its artillery battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, and paved the way for the Union to occupy the town of Jacksonville, Florida.

From 21-23 October, Private Daniel Battaglia participated in his regiment’s first major combat experience—the Battle of Pocotaligo in South Carolina. Eighteen enlisted men from the 47th were killed; another 114 were wounded. Led by brigade commander, Colonel Tilghman H. Good, and regimental commander, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the 47th met heavily fortified Confederate troops in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina—including at Frampton’s Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge. Their goal was to destroy the bridge and disrupt the enemy’s ability to supply itself and transport its soldiers via railroad.

Battered by cannons from a Confederate battery and rifle fire from the surrounding forests, the Union regiments grappled with the Confederates where they found them, pursuing enemy troops for four miles as they retreated to the bridge where the 47th then relieved the 7th Connecticut. But the Confederates were just too well fortified. After two hours of intense fighting in an unsuccessful attempt to take the ravine and bridge, sorely depleted ammunition supplies forced the 47th’s withdrawal to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th Pennsylvania were significant. Captain Charles Mickley was killed and Captain George Junker mortally wounded. First Lieutenant William Geety was grievously wounded, but survived.

The 47th Pennsylvania returned to Hilton Head on 23 October, where members of the regiment served as the funeral Honor Guard for the commander of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps and Department of the South, General Ormsby M. Mitchel, who died from yellow fever on 30 October. The Mountains of Mitchel, a region of the South Pole on Mars discovered by Mitchel in 1846 while working as an astronomer at the University of Cincinnati, and Mitchelville, the first Freedmen’s town created after the Civil War, were both later named for him. The men of the 47th Pennsylvania were the soldiers given the high honor of firing the salute over his grave.

1863

Having been ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, much of 1863 was spent garrisoning federal installations in Florida as part of the U.S. Army’s 10th Corps, Department of the South. The men of E Company again joined with Companies A, B, C, G, and I in guarding Key West’s Fort Taylor while Companies D, F, H, and K garrisoned Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the coast of Florida.

While at Fort Taylor from March through December of 1863, men from the 47th were assigned to fell trees and build roads while continuing to strengthen the facility’s fortifications. In addition, they were also sent out on skirmishes.

The time spent in Florida by the men of Company A and their fellow Union soldiers was notable not just for these reasons—but for their commitment to preserving the Union. Many of the 47th Pennsylvanians who could have returned home, their heads held high upon expiration of their terms of service, chose instead to re-enlist in order to finish the fight.

1864

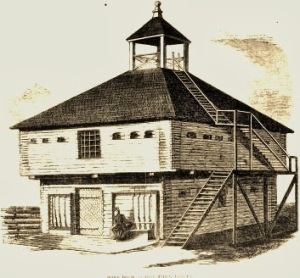

In early January 1864, the 47th was ordered to expand the reach of the Union Army. Captain Graeffe, Company A’s commanding officer, and a group of men were assigned to special duty which involved raids on area cattle herds in order to provide food for the growing Union troop presence, taking them as far north as Fort Myers (see illustration of the fort’s blockhouse at right). Abandoned in 1858 after the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians, the fort was ordered to be revitalized by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade while also offering shelter for pro-Union supporters and those fleeing Rebel troops, including Confederate Army deserters and escaped slaves. According to Schmidt:

In early January 1864, the 47th was ordered to expand the reach of the Union Army. Captain Graeffe, Company A’s commanding officer, and a group of men were assigned to special duty which involved raids on area cattle herds in order to provide food for the growing Union troop presence, taking them as far north as Fort Myers (see illustration of the fort’s blockhouse at right). Abandoned in 1858 after the U.S. government’s third war with the Seminole Indians, the fort was ordered to be revitalized by General D. P. Woodbury, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the Gulf, District of Key West and the Tortugas, to facilitate the Union’s Gulf Coast blockade while also offering shelter for pro-Union supporters and those fleeing Rebel troops, including Confederate Army deserters and escaped slaves. According to Schmidt:

Capt. Richard A. Graeffe, accompanied by Assistant Surgeon William F. Reiber, commanded the main portion of Company A which boarded ship on Monday, January 4 and sailed the following day, Tuesday, for Fort Myers, on the Caloosahatchee River fifteen air miles southeast of Charlotte Harbor. The company was transported on board the Army quartermaster schooner Matchless, after having embarked the day before, and was accompanied by the steamer U.S.S. Honduras commanded by Lt. Harris, and with Gen. Woodbury aboard. Lt. Harris was directed to tow the Matchless if necessary.

Punta Rassa was probably the location where the troops disembarked, and was located on the tip of the southwest delta of the Caloosahatchee River … near what is now the mainland or eastern end of the Sanibel Causeway… Fort Myers was established further up the Caloosahatchee at a location less vulnerable to storms and hurricanes. In 1864, the Army built a long wharf and a barracks 100 feet long and 50 feet wide at Punta Rassa, and used it as an embarkation point for shipping north as many as 4400 Florida cattle….

Capt. Graeffe and company were disembarked on the evening of January 7, and Gen. Woodbury ordered the company to occupy Fort Myers on the south side of the Caloosahatchee, about 12 miles from its mouth and 150 miles from Key West. Shortly after, [a detachment of men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company stationed on Useppa Island] was also ordered to proceed to Fort Myers and join the main body of Company A, the entire command under direct orders of the General who was in the area…. Gen. Woodbury returned to Key West on the Honduras prior to January 19, and the command was left in charge of Capt. Graeffe who dispatched various patrols in search of refugees for enlistment and for activities involving Confederate cattle shipments.

Company A’s muster roll provides the following account of the expedition under command of Capt. Graeffe: ‘The company left Key West Fla Jany 4. 64 enroute to Fort Meyers Coloosahatche River [sic] Fla. were joined by a detachment of the U.S. 2nd Fla Rangers at Punta Rossa Fla took possession of Fort Myers Jan 10. Captured a Rebel Indian Agent and two other men.’

A draft Environmental Impact Statement prepared in 2010 for the Everglades National Park partially documents the time of Richard Graeffe and the men under his Florida command this way:

A small contingent of 20 men and two officers from the Pennsylvania 47th Regiment, led by Captain Henry Crain of the 2nd Regiment of Florida, arrived at the fort on January 7, 1864. A short time later, the party was joined by another small detachment of the 47th under the command of Captain Richard A. Graeffe. Over a short period, increasing reinforcements of the fort led to increasing cattle raids throughout the region. A Union force so far into Confederate land did not go well with Confederate loyalists. The fact that so many men stationed at the post were black soldiers from the newly created U.S. Colored Troops was particularly aggravating. The raids were so antagonizing that the Confederates created a Cattle Guard Battalion called the “Cow Cavalry” to repulse Union raiders. The unit remained a primary threat to the Union soldiers carrying out raids and reconnaissance missions from Brooksville to as far south as Lake Okeechobee and Fort Myers.

Early on, according to Schmidt, Captain Graeffe sent the following report to Woodbury:

“At my arrival hier [sic] I divided my forces in three detachment, viz one at the Hospital one into the old guardhouse and one into the Comissary [sic] building, the Florida Rangers I quartered into one of the old Company quarters, I set all parties to work after placing the proper pickets and guards at the Hospital i have build [sic] and now nearly finished a two story loghouse of hewn and square logs 12 inches through seventeen by twenty-two fifteen feet high with a cupola onto the roof of six feet high and at right angle with two lines of picket fences seven feet high. i shall throw up a half a bastion around it as soon as completed. around the old guardhouse i have thrown up a bastion seven feet through at the foot and three feet on the top nine feet high from the bottom of the ditch and five on the inside. I also build [sic] a loghouse sixteen by eighteen of two storys [sic] Southeast of the Commissary building with a bastion around it at right angles with a picket fence each bastion has the distance you recomandet [sic] from the loghouses 20 feet on the sides and 20 to the salient angle, i caused to be dug a well close to bl. houses and inside of the bastions at each Station inside they are all comfortable fitted up with stationary bunks for the men without interfering with the defence [sic] of the work outside of the Bastions and inside the picket fense i have erected small kitchens and messrooms for each station, i am building now a guardhouse build [sic] of square hewn logs sixteen by sixteen two storys high the lower room to be used for the guard and the upper one as a prison, the building to be used for defence [sic] (in case of attack) by the Rangers each work is within view and supporting distance from the other; Capt. Crane with a detachment of his men repaired the wharf, which is in good condition now and fit for use, the bakehouse i got repaired, and the fourth day hier [sic] we had already very good fresh bread; the parade ground is in a good condition had all the weeds mowed off being to [sic] green to burn. i intend to fit up a schoolroom and church as soon as possible.”

Muster rolls for Company A from this period noted that “a detachment of 25 men crossed over to the north west side of the river” on 16 January and “scoured the country till up to Fort Thompson a distance of 50 miles,” where they “encountered a Rebel Picket who retreated after exchanging shots.” Making their way back, they swam across the river, and reached the fort on 23 January. Meanwhile, while that group was still away, Captain Graeffe ordered a smaller detachment of eight men to head out on 17 January in search of cattle. Finding only a few, they instead took possession of four barrels of Confederate turpentine, which were later disposed of by other Union troops.

Graeffe’s men also captured three Confederate sympathizers at the fort, including a blockade runner and spy named Griffin and an Indian interpreter and agent named Lewis. Charged with multiple offenses against the United States, they were transported to Key West, where they were kept under guard by the Provost Marshal—Major William Gausler, third-in-command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

This phase of duty lasted until sometime in February of 1864. The detachment of the 47th which served under Graeffe at Fort Myers is labeled as the Florida Rangers in several publications, including The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, prepared by Lieutenant-Colonel Robert N. Scott, et. al. (1891). Several of Graeffe’s hand drawn sketches of Fort Myers were published in 2000 in Images of America: Fort Myers by Gregg Tuner and Stan Mulford.

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had already left on the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer—the Charles Thomas—on 25 February 1864, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K of the 47th Pennsylvania headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by other members of the regiment from Companies E, F, G, and H who had been stationed at Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas. Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost fully reconstituted regiment moved by train on 28 February to Brashear City before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps, and became the only Pennsylvania regiment to serve in the Red River Campaign of Union General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A were effectively placed on a different type of detached duty in New Orleans while they awaited transport to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of 245 Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April, and reached Alexandria with those prisoners on 9 April.

But they had missed the two bloodiest combat engagements that the 47th Pennsylvania would endure during the Red River Campaign—the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield on 8 April and the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April. According to Schmidt, Company A was soon ordered to return the Confederate prisoners to New Orleans, and officially ended their detached duty on 27 April when they rejoined the main regiment’s encampment at Alexandria.

This means that the men from Company A also missed a third combat engagement—the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry”), which took place on 23 April.

From late April through mid-May 1864, the now-fully reassembled 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and their fellow brigade members helped to build “Bailey’s Dam” near Alexandria, enabling federal gunboats to successfully navigate the fluctuating water levels of the Red River.

Beginning 13 May, the members of Company A moved with the majority of the 47th from Simmsport, across the Atchafalaya, and on to Morganza, before reaching New Orleans on 20 June. On Independence Day, they received orders to return to the East Coast for further duty.

Throughout this difficult campaign and their earlier years in the Deep South, a fair number of the 47th who had managed to survive intense combat were lost to another challenging foe—disease. Typhoid, yellow jack and even dysentery claimed men whose immune systems were unprepared for close military camp life and their sudden exposure to a more tropical climate. Among those from A Company who did not survive the Red River experience were: Private Josiah Stocker, who died at the Union’s General Hospital in New Orleans on 17 May 1864, and Private Jacob Trabold, who died in Morganza on 27 June. Privates George Bohn and George Bollan lost their respective battles on 20 and 28 June. Left behind while their regiment headed north, Privates J. Williamson and Michael Andrew died on 13 and 14 July.

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

Still able and willing to fight after their time in Bayou country, the soldiers of Company A and the men from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Companies C, D, E, F, H, and I steamed aboard the McClellan beginning 7 July 1864.

Following their arrival in Virginia and a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln on 12 July, they joined up with General David Hunter’s forces at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July 1864. There, they fought in the Battle of Cool Spring and, once again, assisted in defending Washington, D.C. while also helping to drive Confederate troops from Maryland.

Attached to the Middle Military Division, Army of the Shenandoah from August through November of 1864, the men of the 47th Pennsylvania were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Records of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers confirm that the regiment was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, Virginia in early August 1864, and engaged in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville and other locations within the vicinity (Middletown, Charlestown and Winchester) as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

From 3-4 September, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in the Battle of Berryville, and engaged in related post-battle skirmishes with the enemy over subsequent days.

Two weeks later, on 18 September 1864, Private Daniel Private Battaglia was honorably discharged from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers upon expiration of his three-year term of service; however, he was not yet done helping to preserve the Union of his adopted homeland.

Service with the 4th Regiment, New Jersey Infantry (Late 1864 — Mid-1865)

On 30 December 1864, Daniel Battaglia enrolled for a new, three-year term of Civil War service, signing up to fight as a substitute with Company A of the 4th Regiment, New Jersey Infantry. Mustering in as a Private, major engagements during his term of service with the 4th New Jersey included:

- Hatcher’s Run, Virginia (5-7 February 1865)

- Fort Stedman, Virginia (25 March 1865)

- Capture of Petersburg, Virginia (2 April 1865)

- Sailors’ Creek, Virginia (6 April 1865)

- High Bridge, Farmville, Virginia (7 April 1865), and

- Lee’s Surrender at Appomattox, Virginia (9 April 1865).

Finally, on 9 July 1865, Private Daniel Battaglia honorably mustered out of Civil War service, and returned to civilian life.

After the War

As the end of the 19th century loomed, Daniel Battaglia battled serious mental health issues. Admitted to the U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Hampton, Virginia, he was described as having never married and also as suffering from senility. The home’s administrators had been unable to locate an address for the only next of kin listed for him, George Battaglia, but did note that, if Daniel were able to be released at a future date, his residence subsequent to discharge would be Crosswicks in Burlington County, New Jersey.

Since this discharge was not possible, his attorney helped him to file for his U.S. Civil War Pension in 1904. His illness worsening, Daniel Battaglia was eventually transferred to St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C., where 0n 17 March 1909, he passed away.

The Government Hospital for the Insane, renamed by the U.S. Congress as St. Elizabeths (public domain).

* Note: Initially known as the Government Hospital for the Insane until its name was formally changed by the U.S. Congress to St. Elizabeths (the name used by patients when writing letters home due to the stigma associated with mental illness), St. Elizabeths was the first psychiatric hospital to be operated by the United States government and was, according to the Library of Congress, “a remarkable innovation in this type of institution marking a shift away from incarceration treatment toward active therapeutic treatment of mental illness.”

A Hero’s Rest

Following his death, Daniel Battaglia’s personal effects were appraised by Hampton Soldiers’ Home administrators as “None” while the Washington Post reported his passing in its 20 March 1909 death listings simply as: “Daniel Battaglia, 80 years, Govt. Hosp. Insane.”

Although the newspaper failed to convey the full story of Private Daniel Battaglia, his service to a grateful nation has not been forgotten by his adopted homeland.

This emigrant from Switzerland who fought valiantly to preserve America’s Union at great personal cost was given the honor of a hero’s resting spot, and was interred at Arlington National Cemetery. Now at peace with his fellow Union Army comrades, his grave site is visited each year during “Flags In,” when the members of the U.S. Army’s Old Guard place hundreds of thousands of flags on the graves of America’s fallen prior to Memorial Day.

When visiting Arlington, Private Daniel Battaglia’s grave may be found in Arlington’s Section 17, Site 17543. Say hello and thank you when you’re in town.

Sources:

1. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

2. Civil War Veterans’ Card File (Daniel Battaghlia). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

3. “Deaths.” Washington, D.C.: Washington Post, 20 March 1909.

4. District of Columbia, Deaths and Burials, 1840-1964. Utah: FamilySearch.

5. Historical Register of National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (Daniel Battaglia, Southern Branch Hampton, Virginia, 1895-1909), in U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs Record Group 15 (NARA Microfilm M1749). Washington D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

6. National Cemetery Interment Control Form (Daniel Battaglia), in U.S. Office of the Quartermaster General Record Group 92. College Park, Maryland: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

7. Nationwide Gravesite Locator (online records). Washington, D.C. U.S. National Cemetery Administration and U.S. National Park Service.

8. “Record of Officers and Men of New Jersey in the Civil War, 1861-1865, Vol. 1, William S. Stryker, Adjutant General.” Trenton, New Jersey: New Jersey State Archives.

9. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

10. U.S. Census (1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

11. U.S. Civil War Pension Index (Application No: 1309, Certificate No: 1085454, filed from Pennsylvania by the veteran and his attorney, H. Nachtigall[?], on 23 February 1904). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.