One of the many German-speaking members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry who fought to preserve America’s Union during the American Civil War, Aaron Fink was a simple shoemaker whose life lessons and lasting influence would be felt from the Lehigh Valley region of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania in the mid-nineteenth century to the State of Kansas, where one of his sons would ultimately settle, become a successful merchant, and join the Patriotic Order of the Sons of America before drawing his final breath in 1946.

Formative Years

Born in Salisbury Township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania on 4 November 1823 (alternate birth date: 14 October), Aaron Fink was a son of Solomon Fink (1792-1868), and Susanna (Schleider) Fink, and the grandson of Peter and Maria Elizabeth Finck. His grandfather had emigrated from the Duchy of Wittenberg (now Germany) in 1749, arriving in Philadelphia aboard the Patience on 19 September of that year.

Baptized at the Moravian Church in Emaus (now spelled “Emmaus”) in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania on 1 February 1824, Aaron Fink resided in Lehigh County during his formative years with his parents and siblings: Hanna (1813-1910; approx. years of birth and death), Johannes (1815-1900, approx. years of birth and death), William (1817-1887), Andreas J. (1819-1865; also known as “Andrew”), Caroline (1825-1897), Sarah (1828-1887), Ephraim (1830-1908), Matilda (1833-1884), and Charles Henry Fink (1835-1875). His sister Caroline went on to marry John Worman (1823-1901) while sister Matilda wed Gideon Kemmerer (1828-1913) and William I. Vogenitz (1831-1881).

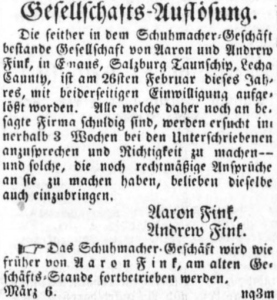

Aaron and Andrew Fink, shoemakers in Allentown, asked their customers to settle their overdue accounts (Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, 6 March 1848, public domain).

At the age of 22, Aaron Fink also wed, taking as his bride a native of Whitehall Township in Lehigh County—Maria Anna Kemmerer (1826-1913). Born on 19 May 1826, Maria Anna was a daughter of Solomon and Magdalena Kemmerer, and was known more commonly as “Mary.” The Rev. Samuel Hess officiated at Aaron and Mary Fink’s wedding ceremony in the Northampton County community of Hellertown on 5 May 1845.

Afterward, Aaron Fink resided with his new bride in Allentown, Lehigh County. They made ends meet on his wages as a shoemaker in the nearby Borough of Emaus [now spelled as “Emmaus”]. In addition to census and other records which confirm his occupation, notices in Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, a Lehigh Valley newspaper published in Allentown during this time, described him as a “Schuhmacher.”

But all was not smooth sailing during these early years. In 1848, newspapers alerted readers that Aaron Fink and his older brother, Andreas, were frustrated by customers who owed money to their shoemaking firm for services that had already been completed. Roughly translated, these notices stated that they would greatly appreciate it if those customers whose accounts were in arrears would pay their bills without further delay.

Fortunately for the pair, business in the Lehigh Valley apparently picked up enough for for the Fink brothers to keep at it. According to the 1850 federal census, both brothers were still working in the trade and, by the start of the next decade, Andrew’s son and Aaron’s nephew—Alvin Fink, was apprenticed to Andrew (who was described on the 1860 federal census as a Master Boot and Shoemaker).

As their business grew, so did both brothers’ families. On 21 April 1850, slightly more than five years after they were married, Aaron and Mary Fink greeted the arrival of their first child, George S. Fink (1850-1933). A second son, “Pharus,” arrived sometime around 1852. Shown on the 1860 federal census, but not listed on other census records or in the U.S. Civil War Pension paperwork for Aaron and Mary Fink, Pharus appears to have died in childhood (before 1870).

Their third son opened his eyes at the Fink’s Allentown home for the first time on 10 November 1858. Unfortunately, much confusion was created in federal census and Civil War pension records regarding the spelling of this child’s name due to incorrect translations from the German/”Pennsylvania Dutch” spoken and written by the parents, their minister and physicians. The name of the Fink’s third son appears in various records as “Alfer Dewees Fink,” “Alpheus Fink,” and “Alfred Fink.”

His name, as confirmed by federal census records later in life, was “Alpheus Dewees Fink”—but he preferred “A. D. Fink.”

By the dawn of the next decade, Aaron Fink and his family were residing in Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe) in Carbon County, Pennsylvania, according to the 1860 federal census. They apparently returned to Allentown by 1861, however, because Aaron Fink’s Civil War records noted that he was a resident of that borough at the time of his enlistment for military service. The children present in the 1860 Fink household were: George (aged 10), “Pharsus” (aged 8), and Alfred (aged 1).

The Civil War

The residents of Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley were treated, during the first quarter of 1861, to a steady barrage of news regarding the rising tensions between America’s North and South. On 17 April 1861, German-speaking Allentonians learned that Fort Sumter had fallen to Confederate forces just days earlier. Der Lecha Caunty Patriot delivered the news with the headline, “Der kreig begonnen!” (“The war started!”), and continued with regular coverage of the Civil War’s progress.

Aaron Fink became one of those men who enlisted during that first Civil War summer. Enrolling on 20 August 1861 at Allentown, he officially mustered in for duty on 30 August at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County as a Corporal with Company B of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. This newly formed regiment was founded by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, who later went on to become a three-time mayor of Allentown. Company B, one of the first two of four companies from the city of Allentown to muster in with the regiment, was raised and led by Emanuel P. Rhoads, grandson of Peter Rhoads, Jr., a former Northampton Bank president. E. P. Rhoads had performed his Three Months’ Service during the opening days of the war as a First Lieutenant with the Allen Rifles, a respected local militia unit that helped to defend the nation’s capital as part of Company I of the 1st Regiment, Pennsylvania Infantry.

Military records at the time of his own enlistment described Corporal Aaron Fink as a 37-year-old shoemaker and resident of Allentown who was 5’7″ tall with black hair, gray eyes and a dark complexion.

Following a brief training period in light infantry tactics, the 47th Pennsylvanians were shipped by rail to Washington, D.C. Stationed about two miles from the White House, they pitched their tents at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, beginning 21 September. Henry D. Wharton, a Musician with the regiment’s C Company, penned a colorful update about the regiment for the Sunbury American newspaper on 22 September:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

On 24 September, Corporal Aaron Fink became part of the federal military service, mustering in with great pomp and gravity to the U.S. Army with his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians. Three days later, on a rainy 27 September, the regiment was assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania was on the move again. Ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey, the Mississippi rifle-armed Keystone Staters marched behind their regimental band until reaching Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (165 steps per minute using 33-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they arrived at Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, were situated close to the headquarters of Union Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (also known as “Baldy”), and were now part of the massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Camp Griffin, Virginia

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” for the large chestnut tree located within their lodging’s boundaries. The site would eventually become known to the men as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly 10 miles from Washington, D.C.

On 11 October, the 47th Pennsylvania marched in the Grand Review at Bailey’s Cross Roads. Also around this time, companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left-wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops. In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday, 22 October, the 47th engaged in a Divisional Review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” In late October, according to Schmidt, the men from Companies B, G and H woke at 3 a.m., assembled a day’s worth of rations, marched four miles from camp, and took over picket duties from the 49th New York:

Company B was stationed in the vicinity of a Mrs. Jackson’s house, with Capt. Kacy’s Company H on guard around the house. The men of Company B had erected a hut made of fence rails gathered around an oak tree, in front of which was the house and property, including a persimmon tree whose fruit supplied them with a snack. Behind the house was the woods were the Rebels had been fired on last Wednesday morning while they were chopping wood there.

In his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed still more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review overseen by the regiment’s founder, Colonel Good, followed by afternoon brigade and division drills. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.” As a reward—and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

The frequent marches, coupled with guard duty in rainy weather, gradually began to wear the men down, and a number of 47th Pennsylvanians fell ill with fever. Several contracted Variola (smallpox), which also felled Confederate troops stationed nearby. Sent back to Union Army hospitals in Washington, D.C., at least two members of the 47th died there while receiving treatment.

1862

U.S. Naval Academy Barracks and temporary hospital, Annapolis, Maryland, circa 1861-1865 (public domain).

Next ordered to move from Virginia back to Maryland, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers left Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles, they reached the railroad station at Falls Church, and were then shipped by rail to Alexandria. From there, they sailed the Potomac via the steamship City of Richmond to the Washington Arsenal, where they were reequipped, and marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington.

The next afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvanians hopped cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

According to Schmidt and letters home from members of the regiment, those preparations ceased on Monday, 27 January, at 10 a.m. when:

The regiment was formed and instructed by Lt. Col. Alexander ‘that we were about drumming out a member who had behaved himself unlike a soldier.’ …. The prisoner, Pvt. James C. Robinson of Company I, was a 36 year old miner from Allentown who had been ‘disgracefully discharged’ by order of the War Department. Pvt. Robinson was marched out with martial music playing and a guard of nine men, two men on each side and five behind him at charge bayonets. The music then struck up with ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the procession was marched up and down in front of the regiment, and Pvt. Robinson was marched out of the yard.

Reloading then resumed. By that afternoon, when the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers commenced boarding the Oriental, they were ferried to the big steamship by smaller steamers. The officers boarded last and, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, they steamed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. They were headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

Corporal Aaron Fink and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians arrived in Key West in February, and were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor. During the weekend of Friday, 14 February, the regiment introduced its presence to locals as it paraded through the streets of the city. That Sunday, a number of the men satisfied their spiritual needs by attending services at local churches. While here, the men of the 47th drilled in heavy artillery and other tactics—often as much as eight hours per day. They also felled trees, built roads and strengthened the installation’s fortifications. Their time was made more difficult by the prevalence of disease. Many of the 47th’s men lost their lives to typhoid and other tropical diseases, or to dysentery and other ailments spread from soldier to soldier by poor sanitary conditions.

As the first embers of spring were sparking back home in the Lehigh Valley, Aaron Fink’s wife and young sons greeted the arrival of their family’s newest addition—Corporal Fink’s daughter, Mary Malosina Fink, who was born in Allentown on 1 April 1862.

Ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina from mid-June through July, the 47th Pennsylvania camped near Fort Walker and then quartered in the Beaufort District, Department of the South. Duties of 3rd Brigade members at this time involved hazardous picket duty to the north of their main camp.

According to Pennsylvania military historian, Samuel P. Bates, the 47th’s soldiers were known for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” and “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan.”

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July).

On 30 September the 47th was sent on a return expedition to Florida where B Company participated with its regiment and other Union forces from 1 to 3 October in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff. Led by Brigadier-General Brannan, the 1,500-plus Union force disembarked from gunboat-escorted troop carriers at Mayport Mills and Mount Pleasant Creek. With the 47th Pennsylvania in the lead and braving alligators, skirmishing Confederates and killer snakes, the brigade negotiated 25 miles of thickly forested swamps in order to capture the bluff and pave the way for the Union’s occupation of Jacksonville, Florida.

Integration of the Regiment

On 5 and 15 October 1862, respectively, the 47th Pennsylvania made history as it became an integrated regiment, adding to its muster rolls a Black teen and several young to middle-aged Black men who had endured plantation enslavement in Beaufort, South Carolina:

- Just 16 years old at the time of his enlistment, Abraham Jassum joined the 47th Pennsylvania from a recruiting depot on 5 October 1862. Military records indicate that he mustered in as “negro undercook” with Company F at Beaufort, South Carolina. Military records described him as being 5 feet 6 inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, and stated that his occupation prior to enlistment was “Cook.” Records also indicate that he continued to serve with F Company until he mustered out at Charleston, South Carolina on 4 October 1865 when his three-year term of enlistment expired.

- Also signing up as an Under Cook that day at the Beaufort recruiting depot was 33-year-old Bristor Gethers. Although his muster roll entry and entry in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File in the Pennsylvania State Archives listed him as “Presto Gettes,” his U.S. Civil War Pension Index listing spelled his name as “Bristor Gethers” and his wife’s name as “Rachel Gethers.” This index also includes the aliases of “Presto Garris” and “Bristor Geddes.” He was described on military records as being 5 feet 5 inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a black complexion, and as having been employed as a fireman. He mustered in as “Negro under cook” with Company F on 5 October 1862, and mustered out at Charleston, South Carolina on 4 October 1865 upon expiration of his three-year term of service. Federal records indicate that he and his wife applied for his Civil War Pension from South Carolina.

- Also attached initially to Company F upon his 15 October 1862 enrollment with the 47th Pennsylvania, 22-year-old Edward Jassum was assigned kitchen duties. Records indicate that he was officially mustered into military service at the rank of Under Cook with the 47th Pennsylvania at Morganza, Louisiana on 22 June 1864, and then transferred to Company H on 11 October 1864. Like Abraham Jassum, Edward Jassum also continued to serve with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers until being honorably discharged on 14 October 1865 upon expiration of his three-year term of service.

More men of color would continue to be added to the 47th Pennsylvania’s rosters in the weeks and years to come.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

From 21-23 October, the 47th engaged Confederate forces in the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina. Landing at Mackay’s Point under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander, the men of the 47th were placed on point once again. This time, however, their luck ran out.

Their brigade was bedeviled by snipers and faced massive resistance from an entrenched Confederate battery, which opened fire on the Union troops as they headed through an open cotton field.

Corporal Aaron Fink and others from his regiment who were trying to reach the higher ground of the Frampton Plantation were pounded by Confederate artillery and peppered by minie balls fired from the rifles and muskets of Confederate infantrymen hidden in the surrounding forests.

In spite of the mortal danger they faced, the 47th Pennsylvanians and other Union troops grappled with the Confederates where they found them, and pursued the Rebels for four miles as they retreated to the bridge. There, the 47th relieved the 7th Connecticut.

But the enemy was just too well armed. After two hours of intense fighting as they attempted to take the ravine and bridge, depleted ammunition finally forced Union leaders to order the 47th to withdraw to Mackay’s Point.

Losses for the 47th Pennsylvania at Pocotaligo were significant. Two officers and 18 enlisted men died; another two officers and 114 enlisted were wounded—several of whom were injured so grievously that they could no longer continue serving.

U.S. General Hospital, Hilton Head, South Carolina, facing the ocean/Port Royal Bay/Broad River, medical director’s residence, left foreground, circa 1861-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

One of the fallen that day was Corporal Aaron Fink. Shot in the right leg during the heavy fighting at the Frampton Plantation on 22 October 1862, he was treated as best as his on-the-move comrades and regimental surgical personnel could before being carried from the scene of battle and stabilized behind Union lines.

He was then transported back to Hilton Head, where he was able to receive more advanced care.

Sadly, the wounds he had sustained while fighting to preserve the Union of his nation were too severe. According to the Army death ledger entry for his case, he died from “Vulnus Sclopeticum” (a gunshot wound) on 5 November 1862 at the Union Army Hospital at Hilton Head, South Carolina.

* Note: While some records documented that Aaron Fink was shot in the right leg, his wife stated in a U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension affidavit that he had been wounded below the knees in both legs.

His death was certified by surgeon, J.E. Semple, ASUSA, as is shown in this image below:

This entry in the U.S. Register of Deaths of U.S. Volunteer Soldiers confirms the 5 November 1862 death from gunshot wounds of Corporal Aaron Fink, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (public domain; click twice to enlarge).

Confusion regarding a soldier’s status was not unusual in those early days. The federal government had not had effective plans in place for identifying and burying soldiers when the first massive bloodletting occurred at Antietam, and even after records management improved, there were still often errors because physicians, army clerks and chaplains were dealing with carnage on an unimaginable scale.

A good example of this confusion is the case of Corporal Aaron Fink, whose hometown newspaper, Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, had only apparently received word of his injury when it initially reported in its 5 November 1862 edition (the day that he died) that he was “Verwundet” (wounded). The newspaper’s 3 December 1862 edition finally made clear that Corporal Fink had died, and reported that Allentown undertaker Paul Balliet had traveled to South Carolina to retrieve Corporal Fink’s remains and those of several other 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers:

A very rough translation of Allentown’s Der Lecha Caunty Patriot article regarding the exhumation and reburial reads as follows:

Returned

Mr. Paul Balliet, an Allentown undertaker and some others from our towns here, arrived last Saturday after a 14-day trip to Beaufort, South Carolina to bring back the bodies of Henry A. Blumer, Aaron Fink, Henry Zeppenfeld, and Capt. George Junker, and return the bodies of these aforementioned men to their relatives.

Capt. Junker’s family lives in Hazelton, where his body was immediately interred.

According to Schmidt, Corporal Fink’s remains were initially interred in Grave No. 54 at the Hilton Head Military Cemetery before being exhumed, returned to Allentown and reburied there in Section A, Lot No. 446 of the Union-West End Cemetery.

A Widow Begins a New Life

Corporal Aaron Fink’s widow eventually recovered from her shock and rebuilt her life. The three young Fink children also survived, and grew to adulthood.

To learn more about what happened to Corporal Aaron Fink’s widow and children, read part two of this biographical sketch, “From Fink to Bornman and Beyond — A Civil War Widow and Fatherless Children Move On.”

* To view more of the key U.S. Civil War Pension records related to the Fink family, visit our Aaron Fink and Family Collection.

Sources:

1. Aaron and Andrew Fink, in “Gesellschafts—Auflösung.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, 6 March 1848.

2. Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

3. Bornman, Mrs. Maria Anna and Conrad Bornmann, in Funeral Ledgers, in Emmaus Moravian Church Records, in Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records (Reel: 539). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

4. Bornman, Mary A., in Old Moravian Cemetery burial records, in Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records (Reel: 562). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

5. Fink, Aaron (Veterans’ Grave Registration Record), in Civil War Grave Registrations Collection, Whitehall Township Public Library, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: State Library of Pennsylvania.

6. “Fink, Aaron,” in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

7. Fink, Aaron, Mary Fink and Mary A. Bornman, in Probate Records, 1863. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Lehigh County Register of Wills.

8. Fink, Aaron, in Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, U.S. Adjutant General’s Office. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration: 1861-1865.

9. Fink, Aaron and Mary (Kemmerer) Fink, in U.S. Civil War Widows’ Pension Files. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives.

10. Fink Family Birth, Marriage and Burial Records (various churches in Lehigh County, etc.), in Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

11. Fink Family Death Certificates (Mary M. Becker, George S. Fink). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

12. Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

13. “Solomon Fink Family Reunion on Sept. 18.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 4 September 1937.

14. U.S. Census (1840, 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940). Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

15. “Zurückgefehrt.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, 3 December 1862.

You must be logged in to post a comment.