The Union’s Army of the Gulf marched into Alexandria, Louisiana, during the weekend of April 22, 1864 (Harper’s Weekly, public domain; click to enlarge).

Resupplied with ammunition and food by the Union Navy’s fleet of quartermaster ships after reaching Alexandria, Louisiana on April 26, 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and other Union infantry and artillery troops were placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey and assigned to the hard labor of fortification work. Throwing their backs into erecting “Bailey’s Dam,” they helped to create a timber dam that was designed by Bailey to enable the Union Navy’s gunboats and other vessels to be able to travel along the Red River without fear of running aground. This construction was undertaken, according to C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton, because:

The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river.

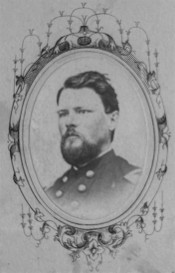

Brigadier-General Joseph Bailey, shonw here circa 1865, was responsible for designing and overseeing the construction of Bailey’s Dam nexr Alexandria, Louisiana during the spring of 1864 (public domain).

Historian Steven Clay notes that, by this point in the Red River Campaign, “The depth of the river was only between three and four feet; it took seven feet of water to get the gunboats over the rocky bottom at the rapids.” To make that happen, Lieutenant-Colonel Bailey had initially floated the idea to build a dam while also sinking “several stone-laden barges to block the passage of water and cause the river to pool up behind them.”

There would be three narrow chutes constructed in the middle to allow passage of the largest gunboats. Then when the depth was sufficient, the boats would steam over the rocks, through the passageways, and into safe and deep waters below the dam.

According to archaeologist and military historian Steven D. Smith, Ph.D. and staff of the Louisiana Archaeological Survey and Antiquities Commission, “Military engineer Joseph Bailey’s presence with the Red River expedition was, in a sense, one of those coincidences of history that sometimes result in turning the course of events.”

His knowledge of engineering was not acquired through formal study at West Point. Instead, he had learned practical engineering on the Wisconsin frontier, where damming was a skill perfected by lumbermen to float logs to their sawmills.

Born in Ashtabula County, Ohio on May 6, 1827, Bailey grew up in Illinois. In 1850 he moved to Wisconsin, where for the next 20 years he was involved in the construction of dams, mills, and bridges. At the beginning of the war, Bailey formed a company of lumbermen and became a captain. Soon, though, his construction genius was recognized and he was supervising various engineering projects for the North, including construction at Fort Dix in Washington D.C….

In 1863 Bailey won distinction at the battle of Port Hudson. There, despite the scoffs of formally trained military engineers, he constructed a gun emplacement in full sight of rebel fortifications and proceeded to silence the Confederate guns. He also built a dam during the siege to refloat two grounded steamboats.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to the Union officer who designed and oversaw its construction, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, this timber dam was built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 to facilitate Union gunboat passage (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

The construction of Bailey’s Dam near Alexandria during the spring of 1864 was described by Lieutenant-Colonel Bailey in a post-construction report to his superiors as follows:

…. Immediately after our army received a check at Sabine Cross-Roads and the retreat commenced I learned through reliable sources that the Red River was rapidly falling. I became assured that by the time the fleet could reach Alexandria there would not be sufficient water to float the gun-boats over the falls. It was evident, therefore, that they were in imminent danger. Believing, as I did, that their capture or destruction would involve the destruction of our army, the blockade of the Mississippi, and even greater disasters to our cause, I proposed to Major-General Franklin on the 9th of April, previous to the battle of Pleasant Hill, to increase the depth of water by means of a dam, and submitted to him my plan of the same. In the course of the conversation he expressed a favorable opinion of it.

During the halt of the army at Grand Ecore on the 17th of April, General Franklin, having heard that the iron-clad gun-boat Eastport had struck a snag on the preceding day and sunk at a point 9 miles below, gave me a letter of introduction to Admiral Porter and directed me to do all in my power to assist in raising the Eastport, and to communicate to the admiral my plan of constructing a dam to relieve the fleet, with his belief in its practicability; also that he thought it advisable that the admiral should at once confer with General Banks and urge him to make the necessary preparations, send for tools, &c. Nothing further was done until after our arrival at Alexandria. On the 26th, the admiral reached the head of the falls. I examined the river and submitted additional details of the proposed dam. General Franklin approved of them and directed me to see the admiral and again urge upon him the necessity of prevailing upon General Banks to order the work to be commenced immediately. There was no doubt that the entire fleet then above the rapids would be lost unless the plan of raising the water by a dam was adopted and put into execution with all possible vigor. I represented that General Franklin had full confidence in the success of the undertaking, and that the admiral might rely upon him for all the assistance in his power. The only preliminary required was an order from General Banks. On the 29th, by order of General Franklin, I consulted with Generals Banks and Hunter, and explained to them the proposed plan in detail. The latter remarked that, although he had little confidence in its feasibility, he nevertheless thought it better to try the experiment, especially as General Franklin, who is an engineer, advised it. Upon this General Banks issued the necessary order for details, teams, &c., and I commenced the work on the morning of the 30th.

I presume it is sufficient in this report to say that the dam was constructed entirely on the plan first given to General Franklin, and approved by him.

During the first few days I had some difficulty in procuring details, &c., but the officers and men soon gained confidence and labored faithfully. The work progressed rapidly, without accident or interruption, except the breaking away of two coal barges which formed part of the dam. This afterward proved beneficial. In addition to the dam at the foot of the falls, I constructed two wing-dams on each side of the river at the head of the falls.

The width of the river at the point where the dam was built is 758 feet, and the depth of the water from 4 to 6 feet. The current is very rapid, running about 10 miles per hour. The increase of depth by the main dam was 5 feet 4 inches; by the wing-dams, 1 foot 2 inches; total, 6 feet 6 inches. On the completion of the dam, we had the gratification of seeing the entire fleet pass over the rapids to a place of safety below, and we found ample reward for our labors in witnessing their result. The army and navy were relieved from a painful suspense, and eight valuable gunboats saved from destruction. The cheers of the masses assembled on the shore when the boats passed down attested their joy and renewed confidence. To Major-General Franklin, who, previous to the commencement of the work, was the only supporter of my proposition to save the fleet by means of a dam, and whose persevering efforts caused its adoption, I desire to return my grateful thanks. I trust the country will join with the Army of the Gulf and the Mississippi Squadron in awarding to him due praise for his earnest and intelligent efforts in their behalf. Major-General Banks promptly issued all necessary orders and assisted me by his constant presence and co-operation. General Dwight, his chief of staff, Colonel Wilson and Lieutenant Sargent, aides-de-camp, also rendered valuable assistance by their personal attention to our wants. Admiral Porter furnished a detail from his ships’ crews, under command of an excellent officer, Captain Langthorne, of the Mound City. All his officers and men were constantly present, and to their extraordinary exertions and to the well-known energy and ability of the admiral much of the success of the undertaking is due….

The crib dam designed by Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey to improve the water levels of the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana, spring 1864 (Joseph Bailey, “Report on the Construction of the Dam Across the Red River,” 1865, public domain).

According to Smith, “Historical documents indicate that Bailey first built his dam just above the lower, downstream rapids.”

By constructing the dam at that particular location, he hoped the water would rise enough behind the dam to allow the gunboats to float over the upper rapids. Then, with the built-up water pressure, the dam could be broken through at the proper time and the gunboats could rush over the lower rapids, carried by the force of the released water.

Following Bailey’s practical nature, the dam was built with any locally available material readily at hand. To do so, he used different methods of construction for each riverbank. On the west (Alexandria) bank, he built the dam of large wooden boxes called cribs. Bailey constructed a number of cribs which were placed side by side from the bank out into the river.

Historical accounts indicate that lumber from Alexandria mills, homes, and barns was quickly stripped for use in building the cribs. Bricks, stone, and even machinery were used to fill and anchor the cribs. Additionally, historical illustrations show that iron bars were placed vertically in the four corners of each crib, to provide a supporting framework….

On the east (Pineville) bank, there were no town buildings to strip for lumber but there was, quite conveniently, a forest. With abundant trees available, Bailey constructed a ‘self-loading’ tree dam. According to historical diagrams, trees were stacked lengthwise with the flow of the stream. The upstream treetops were anchored to the river bottom with stones. The downstream trunks were raised higher than the upstream tops by alternating layers of other logs running perpendicular to, or across, the stream. This technique presented a dam face of logs angled upward with the stream flow. As the river was held back by the log face, the water pressure actually made the dam stronger or ‘self-loading.’

The tree dam designed by Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey for the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana, spring 1864 (Joseph Bailey, “Report on the Construction of the Dam Across the Red River,” 1865, public domain).

Putting readers into the shoes of the Union Army troops on the ground during those days, the 1868 publication, The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, noted that:

Oak, elm, and pine trees … were falling to the ground under the blows of the stalwart pioneers of Maine, bearing with them in their fall trees of lesser growth; mules and oxen were dragging the trees, denuded of their branches, to the river’s bank; wagons heavily loaded were moving in every direction; flat-boats carrying stone were floating with the current, while others were being drawn up the stream in the manner of canal boats. Meanwhile hundreds of men were at work at each end of the dam, moving heavy logs to the outer end of the tree-dam, … wheeling brick out to the cribs, carrying bars of railway iron to the barges, … while on each bank of the river were to be seen thousands of spectators, consisting of officers of both services, groups of sailors, soldiers, camp-followers, and citizens of Alexandria, all eagerly watching our progress and discussing the chances of success.

Initially, according to Smith, the “dam complex” worked well. “By May 6, the water held by the dam had risen 4 feet. By May 8, the water level was up 5 feet 4 inches.” But then the water levels continued to increase to such an extent that “the pressure against the dam became tremendous,” causing the dam to burst.

Two of the barges used in the dam had broken loose, and the water was gushing through. Porter, seeing the crisis, quickly ordered the gunboat Lexington to run the gap….

The Lexington’s run was followed by the three gunboats waiting behind the dam. Had the rest of the fleet been prepared, all of the boats might have escaped at that time. However … valuable time was wasted as the fleet gathered steam to attempt the run. Eventually, the water behind the dam fell and six gunboats still remained trapped.

But the Lexington’s adventure had proven that the dam could work, and troops confidently went back to work. Bailey worried that the dam would break again and decided to leave the 70-foot gap in the dam as it was. But this time he added smaller, lighter dams near the upper rapids. Like the dam sections at the lower rapids, both crib and tree dam methods were employed. These dams helped channel the water while reducing the pressure on the main dam. Thus, instead of relying on one dam to hold back the water until another run could be made, a series of dams were built to create a deep channel of water along the whole course of the shoals in that part of the Red River.

And, at that point, “Bailey’s Dam” became “Bailey’s Dams.”

“Passage of the Fleet of Gunboats Over the Falls at Alexandria, Louisiana, May 1864 (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, July 16, 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

“While the army labored to build the upper dam, the navy … worked to lighten the loads on the trapped gunboats,” according to Smith.

From May 10 through 12, the remaining gunboats above the rapids struggled through the upper shoals to the pool behind the main dam. Yet another dam had to be built to refloat a gunboat that got stuck during this passage. Then on the twelfth of May, the Mound City, the largest gunboat of the fleet, ran for the gap in the main dam. The previous scene was repeated, with thousands lining the banks to watch the excitement. Marching bands played the ‘Star Spangled Banner’ and the ‘Battle Cry for Freedom [sic, ‘Battle Cry of Freedom’].’ Like the Lexington before it, as the Mound City hit the gap, it ground against the rocky river bottom, and then shot through. The next day all of the trapped vessels lay safely below the rapids.

Through it all, members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry put their backs into their work, along with multiple other Union Army soldiers, including men from the 16th and 23rd Ohio Volunteers, the 19th Kentucky, the 23rd and 29th Wisconsin Volunteers, the 24th Iowa, the 24th and 27th Indiana, the 29th Maine, the 77th and 130th Illinois Volunteers, and the 97th and 99th U.S. Colored Infantry.

Lieutenant-Colonel Bailey later stated that his “details labored patiently and enthusiastically by day and night, standing waist deep in the water, under a broiling sun,” adding:

Their reward is the consciousness of having performed their duty as true soldiers, and they deserve the gratitude of their countrymen.

The massive construction project lasted roughly two weeks, according to 47th Pennsylvanian Henry Wharton, but proved to be worth it.

After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’

The Army of the Gulf’s departure, however, also brought shock and heartache; according to Major-General Banks:

Rumors were circulated freely throughout the camp at Alexandria that upon the evacuation of the town it would be burned. To prevent this destruction of property – part of which belonged to loyal citizens – General Grover, commanding the post, was instructed to organize a thorough police, and to provide for its occupation by an armed force until the army had marched for Simmsport [sic, Simmesport]. The measures taken were sufficient to prevent a conflagration in the manner in which it had been anticipated. But on the morning of the evacuation, while the army was in full possession of the town, a fire broke out in a building on the levee, which had been occupied by refugees or soldiers, in such a manner as to make it impossible to prevent a general conflagration. I saw the fire when it was first discovered. The ammunition and ordnance transports and the depot of ammunition on the levee were within a few yards of the fire. The boats were floated into the river and the ammunition moved from the levee with all possible dispatch [sic]. The troops labored with alacrity and vigor to suppress the conflagration, but owing to a high wind and the combustible material of the buildings it was found impossible to limit its progress, and a considerable portion of the town was destroyed.

According to Smith, “It is unclear who started the fires, as some accounts describe soldiers looting and setting fires, while other accounts note that army guards shot looters.” What is known for certain is that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers could not possibly have taken part in Alexandria’s destruction because they had actually left the city before the fire had even begun. According to Henry Wharton:

The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced.

Injured or Sick:

Wolf, Abraham: Private, Company B; developed first signs of rheumatism, a condition that would last for the remainder of his life; also fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the construction of Bailey’s Dam due to poor water quality; subsequently developed hemorrhoids as a direct result of that illness.

Captured and Held as Prisoner of War (POW):

Maul, Adam (alternate spellings: Moll, Moul): Private, Company C; captured by Confederate forces at the Cane River on May 3, 1864 while assigned to duties away from the regiment’s Alexandria, Louisiana encampment—possibly during the construction of Bailey’s Dam; held as a prisoner of war (POW) at Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas until being released as part of a prisoner exchange between the Union and Confederate armies on July 22, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered from his experience, and returned to duty with Company C.

Smith, Frederick: Private, Company D; possibly wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; captured by Confederate States Army troops during that battle and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until his death on May 4, 1864.

Sources:

- Bailey, Joseph. “Report on the construction of the dam across the Red River,” in Report of the Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, at the Second Session Thirty-Eighth Congress, Red River Expedition, Fort Fisher Expedition, Heavy Ordnance. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1865.

- “Bailey’s Dam.” Washington, D.C.: American Battlefield Trust, retrieved online May 6, 2024.

- “Bailey’s Dam,” in Anthropological Study No. 8. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Archaeological Survey and Antiquities Commission, Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism, March 1986.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Clay, Steven E. The Staff Ride Handbook for the Red River Campaign, 7 March-19 May 1864. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: Combat Studies Institute Press, U.S. Army Combined Arms Centers, 2023.

- Dollar, Susan E. “The Red River Campaign, Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana: A Case of Equal Opportunity Destruction,” in Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, vol. 43, no. 4 (Autumn 2002), pp. 411-432, accessed April 22, 2024. Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana Historical Association.

- Moore, Frank, editor. “The Red River Dam,” in The Rebellion Record: A Diary of American Events, vol. 11, pp. 11-12. New York, New York: D. Van Nostrand, 1868.

- Prisoner of War Records, Camp Ford and Camp Groce (47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry). Tyler Texas: Smith County Historical Society, 2010.

- “Report of Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks, U. S. Army, Commanding Expedition and Department of the Gulf” (to Edwin M. Stanton, Secretary of War), in Annual Report of the Secretary of War, in Message of the President of the United States, and Accompanying Documents, to the Two Houses of Congress, at the Commencement of the First Session of the Thirty-Ninth Congress. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1866.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, July 20, 1870.

You must be logged in to post a comment.