Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, U.S. Army (public domain).

“It is hardly necessary to point out to you the extreme military importance of the two works now intrusted [sic, entrusted] to your command. Suffice it to state that they cannot pass out of our hands without the greatest possible disgrace to whoever may conduct their defense, and to the nation at large. In view of difficulties that may soon culminate in war with foreign powers, it is eminently necessary that these works should be immediately placed beyond any possibility of seizure by any naval or military force that may be thrown upon them from neighboring ports….

Seizure of these forts by coup de main may be the first act of hostilities instituted by foreign powers, and the comparative isolation of their position, and their distance from reinforcements, point them out (independent of their national importance) as peculiarly the object of such an effort to possess them.”

— Excerpt from orders issued by Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, commanding officer, United States Army, Department of the South, to Colonel Tilghman H. Good, commanding officer of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in December 1862

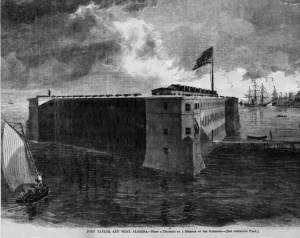

Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, view from the sea, 1946 (vacation photograph collection of President Harry Truman, November 1946 U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

Having been ordered by Union Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan to resume garrison duties in Florida in December 1862, after having been badly battered in the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina two months earlier, the officers and enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were also informed in December that their regiment would become a divided one. This was being done, Brannan said, not as a punishment for their performance, which had been valiant, but to help the federal government to ensure that the foreign governments that had granted belligerent status to the Confederate States of America would not be able to aid the Confederate army and navy further in their efforts to move troops and supplies from Europe and the Deep South of the United States to the various theaters of the American Civil War.

As a result, roughly sixty percent of 47th Pennsylvanians (Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I) were sent back to Fort Taylor in Key West shortly before Christmas in 1862 while the remaining members of the regiment (from Companies D, F, H, and K) were transported by the USS Cosmopolitan to Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas, which was situated roughly seventy miles off the coast of Florida. They arrived there in late December of that same year.

Life at Fort Jefferson

Union Army Columbiad on the Terreplein at Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida (George A. Grant, 1937, U.S. National Park Service, public domain).

Garrison duty in Florida proved to be serious business for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Per records of the United States Army’s Ordnance Department, the defense capabilities of Fort Jefferson in 1863 were impressive—thirty-three smoothbore cannon (twenty-four of which were twenty-four pounder howitzers that had been installed in the fort’s bastions to protect the installation’s flanks, and nine of which were forty-two pounders available for other defensive actions); six James rifles (forty-two pounder seacoast guns); and forty-three Columbiads (six ten-inch and thirty-seven eight-inch seacoast guns).

Fort Jefferson was so heavily armed because it was “key in controlling … shipping in the Gulf of Mexico and was being used as a supply depot for the distribution of rations and munitions to Federal troops in the Mississippi Delta; and as a supply and fueling station for naval vessels engaged in the blockade or transport of supplies and troops,” according to historian Lewis Schmidt.

Large quantities of stores, including such diverse items as flour … ham … coal, shot, shell, powder, 5000 crutches, hospital stores, and stone, bricks and lumber for the fort, were collected and stored at the Tortugas for distribution when needed. Federal prisoners, most of them court martialed Union soldiers, were incarcerated at the fort during the period of the war and used as laborers in improving the structure and grounds. As many as 1200 prisoners were kept at the fort during the war, and at least 500 to 600 were needed to maintain a 200 man working crew for the engineers.

With respect to housing and feeding the soldiers stationed here:

Cattle and swine were kept on one of the islands nearest the fort, called ‘Hog Island’ (today’s Bush Key), and would be compelled to swim across the channel to the fort to be butchered, with a hawser fastened to their horns. The meat was butchered twice each week, and rations were frequently supplemented by drawing money for commissary stores not used, and using it to buy fish and other available food items from the local fishermen. The men of the 7th New Hampshire [who were also stationed at Fort Jefferson] acquired countless turtle and birds’ eggs … from adjacent keys, including ‘Sand Key’ [where the fort’s hospital was located]. Loggerhead turtles were also caught … [and] were kept in the ‘breakwater ditch outside of the walls of the fort’, and used to supplement the diet [according to one soldier from New Hampshire].

Second-tier casemates, lighthouse keeper’s house, sallyport, and lean-to structure, Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, late 1860s (U.S. National Park Service and National Archives, public domain).

In addition, the fort’s “interior parade grounds, with numerous trees and shrubs in evidence, contained … officers’ quarters, [a] magazine, kitchens and out houses,” as well as a post office and “a ‘hot shot oven’ which was completed in 1863 and used to heat shot before firing,” according to Schmidt.

Most quarters for the garrison … were established in wooden sheds and tents inside the parade [grounds] or inside the walls of the fort in second-tier gun rooms of ‘East’ front no. 2, and adjacent bastions … with prisoners housed in isolated sections of the first and second tiers of the southeast, or no. 3 front, and bastions C and D, located in the general area of the sallyport. The bakery was located in the lower tier of the northwest bastion ‘F’, located near the central kitchen….

According to H Company Second Lieutenant Christian Breneman, the walk around Fort Jefferson’s barren perimeter was less than a mile long with a sweeping view of the Gulf of Mexico. Brennan also noted the presence of “six families living [nearby], with 12 or 15 respectable ladies.”

Balls and parties are held regularly at the officers’ quarters, which is a large three-story brick building with large rooms and folding doors.

Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, second-in-command, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, standing next to his horse, with officers from the 47th, Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, circa 1863 (public domain; click to enlarge).

Shortly after the arrival of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers at Fort Jefferson, First Lieutenant George W. Fuller was appointed as adjutant for Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, who had been placed in command of the fort’s operations. Assistant Regimental Surgeon Jacob Scheetz, M.D. was appointed as post surgeon and given command of the fort’s hospital operations, responsibilities he would continue to execute for fourteen months. In addition, Private John Schweitzer of the 47th Pennsylvania’s A Company was directed to serve at the fort’s baker, B Company’s Private Alexander Blumer was assigned as clerk of the quartermaster’s department, and H Company’s Third Sergeant William C. Hutchinson began his new duties as provost sergeant while H Company Privates John D. Long and William Barry were given additional duties as a boatman and baker, respectively.

When Christmas Day dawned, many at the fort experienced feelings of sadness and ennui as they continued to mourn friends who had recently been killed at Pocotaligo and worried about others who were still fighting to recover from their battle wounds.

1863

Unidentified Union Army artillerymen standing beside one of the fifteen-inch Rodman guns installed on the third level of Fort Jefferson in the Dry Tortugas, Florida, circa 1862. Each smoothbore Rodman weighed twenty-five tons, and was able to fire four-hundred-and-fifty-pound shells more than three miles (U.S. National Park Service, public domain).

The New Year arrived at Fort Jefferson with a bang—literally—as the fort’s biggest guns thundered in salute, kicking off a day of celebration designed by senior military officials to lift the spirits of the men and inspire them to continued service. Donning their best uniforms, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers assembled on the parade grounds, where they marched in a dress parade and drilled to the delight of the civilians living on the island, including Emily Holder, who had been living in a small house within the fort’s walls since 1860 with her husband, who had been stationed there as a medical officer for the fort’s engineers. When describing that New Year’s Day and other events for an 1892 magazine article, she said:

On January 1st, 1863, the steamer Magnolia visited Fort Jefferson and we exchanged hospitalities. One of the officers who dined with us said it was the first time in nine months he had sat at a home table, having been all that time on the blockade….

Colonel Alexander, our new Commander, said that in Jacksonville, where they paid visits to the people, the young ladies would ask to be excused from not rising; they were ashamed to expose their uncovered feet, and their dresses were calico pieced from a variety of kinds.

Two days later, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ dress parade was a far less enjoyable one as temperatures and tempers soared. The next day, H Company Corporal George Washington Albert and several of his comrades were given the unpleasant task of carrying the regiment’s foul-smelling garbage to a flatboat and hauling it out to sea for dumping.

As the month of January progressed, it became abundantly clear to members of the regiment that the practice of chattel slavery was as ever present at and beyond the walls of Fort Jefferson as it had been at Fort Taylor and in South Carolina. It seemed that the changing of hearts and minds would take time even among northerners—despite President Lincoln’s best efforts, as illustrated by these telling observations made later that same month by Emily Holder:

We received a paper on the 10th of January, which was read in turns by the residents, containing rumors of the emancipation which was to take place on the first, but we had to wait another mail for the official announcement.

I asked a slave who was in my service if he thought he should like freedom. He replied, of course he should, and hoped it would prove true; but the disappointment would not be as great as though it was going to take away something they had already possessed. I thought him a philosopher.

In Key West, many of the slaves had already anticipated the proclamation, and as there was no authority to prevent it, many people were without servants. The colored people seemed to think ‘Uncle Sam’ was going to support them, taking the proclamation in its literal sense. They refused to work, and as they could not be allowed to starve, they were fed, though there were hundreds of people who were offering exorbitant prices for help of any kind—a strange state of affairs, yet in their ignorance one could not wholly blame them. Colonel Tinelle [sic, Colonel L. W. Tinelli] would not allow them to leave Fort Jefferson, and many were still at work on the fort.

John, a most faithful boy, had not heard the news when he came up to the house one evening, so I told him, then asked if he should leave us immediately if he had his freedom.

His face shone, and his eyes sparkled as he asked me to tell him all about it. He did not know what he would do. The next morning Henry, another of our good boys, who had always wished to be my cook, but had to work on the fort, came to see me, waiting until I broached the subject, for I knew what he came for. He hoped the report would not prove a delusion. He and John had laid by money, working after hours, and if it was true, they would like to go to one of the English islands and be ‘real free.’

I asked him how the boys took the news as it had been kept from them until now, or if they had heard a rumor whether they thought it one of the soldier’s stories.

‘Mighty excited, Missis,’ he replied….

Henry had been raised in Washington by a Scotch lady, who promised him his freedom when he became of age; but she died before that time arrived, and Henry had been sold with the other household goods.

The 47th Pennsylvanians continued to undergo inspections, drill and march for the remainder of January as regimental and company assignments were fine-tuned by their officers to improve efficiency. Among the changes made was the reassignment of Private Blumer to service as clerk of the fort’s ordnance department.

Three key officers of the regiment, however, remained absent. D Company’s Second Lieutenant George Stroop was still assigned to detached duties with the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps aboard the Union Navy’s war sloop, Canandaigua, and H Company’s First Lieutenant William Wallace Geety was back home in Pennsylvania, still trying to recruit new members for the regiment while recovering from the grievous injuries he had sustained at Pocotaligo, while Company K’s Captain Charles W. Abbott was undergoing treatment for disease-related complications at Fort Taylor’s post hospital.

Disease, in fact, would continue to be one of the Union Army’s most fearsome foes during this phase of duty, felling thirty-five members of its troops stationed at Fort Jefferson during the months of January and February alone. Those seriously ill enough to be hospitalized included twenty men battling dysentery and/or chronic diarrhea, four men suffering from either intermittent or bilious remittent fever, and two who were recovering from the measles with others diagnosed with rheumatism and general debility.

Fort Jefferson’s moat and wall, circa 1934, Dry Tortugas, Florida (C. E. Peterson, U.S. Library of Congress; public domain).

The primary reason for this shocking number of sick soldiers was the problematic water quality. According to Schmidt:

‘Fresh’ water was provided by channeling the rains from the fort’s barbette through channels in the interior walls, to filter trays filled with sand; and finally to the 114 cisterns located under the fort which held 1,231,200 gallons of water. The cisterns were accessible in each of the first level cells or rooms through a ‘trap hole’ in the floor covered by a temporary wooden cover…. Considerable dirt must have found its way into these access points and was responsible for some of the problems resulting in the water’s impurity…. The fort began to settle and the asphalt covering on the outer walls began to deteriorate and allow the sea water (polluted by debris in the moat) to penetrate the system…. Two steam condensers were available … and distilled 7000 gallons of tepid water per day for a separate system of reservoirs located in the northern section of the parade ground near the officers [sic, officers’] quarters. No provisions were made to use any of this water for personal hygiene of the [planned 1,500-soldier garrison force]….

Consequently, soldiers were forced to wash themselves and their clothes using saltwater hauled from the ocean. As if that were not difficult enough, “toilet facilities were located outside of the fort.” According to Schmidt:

At least one location was near the wharf and sallyport, and another was reached through a door-sized hole in a gunport, and a walk across the moat on planks at the northwest wall…. These toilets were flushed twice each day by the actions of the tides, a procedure that did not work very well and contributed to the spread of disease. It was intended that the tidal flush should move the wastes into the moat, and from there, by similar tidal action, into the sea. But since the moat surrounding the fort was used clandestinely by the troops to dispose of litter and other wastes … it was a continuous problem for Lt. Col. Alexander and his surgeon.

When it came to the care of soldiers with more serious infectious diseases such as smallpox, soldiers and prisoners were confined to isolation roughly three miles away on Bird Key to prevent contagion. The small island also served as a burial ground for Union soldiers stationed at the fort.

* Note: During this same period, First Lieutenant Lawrence Bonstine was assigned to special duty as Post Adjutant at Fort Taylor in Key West, a position he continued to hold from at least January 10, 1863 through the end of December 1863. Reporting directly to the regiment’s founder and commanding officer, Colonel Tilghman H. Good, he was essentially Good’s right hand, ensuring that regimental records and reports to more senior military officials were kept up to date while performing other higher level administrative and leadership tasks.

On February 3, 1863, Colonel Tilghman Good, visited Fort Jefferson, in his capacity as regimental commanding officer and accompanied by the newly re-formed Regimental Band (band no. 2). Led by Regimental Bandmaster Anton Bush, the ensemble was on hand to perform the music for that evening’s officers’ ball.

Sometime during this phase of duty, Corporal George W. Albert was reassigned to duties as camp cook for Company H, giving him the opportunity to oversee at least one of the formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry while the regiment was stationed in Beaufort, South Carolina. Subsequently assigned to duties as an “Under-Cook,” that Black soldier who fell under his authority was most likely Thomas Haywood, who had been entered onto the H Company roster after enrolling with the 47th Pennsylvania on November 1, 1862.

* Note: This was likely not a pleasant time for Thomas Haywood. One of the duties of his direct superior, Corporal George Albert, was to butcher a shipment of cattle that had just been received by the fort. Both men took on that task on Saturday, February 24—a day that Corporal Albert later described as hot, sultry and plagued by mosquitoes.

Based on Albert’s known history of overt racism, their interpersonal interactions were likely made worse that day by his liberal use of racial epithets, which were a frequent component of the diary entries he had penned during this time—hate speech that has all too often been wrongly attributed to the regiment’s entire membership by some mainstream historians and Civil War enthusiasts without providing actual evidence to back up those claims. There were a considerable number of officers and enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania who strongly supported the efforts of President Lincoln and senior federal government military leaders to eradicate the practice of chattel slavery nationwide with at least several members of the regiment known to be members of prominent abolitionist families in Pennsylvania.

Officers’ quarters and parade grounds, interior of Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, 1898 (U.S. National Park Service and National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

During this same period, Private Edward Frederick of the 47th Pennsylvania’s K Company was readmitted to the regimental hospital for further treatment of the head wound he had sustained at Pocotaligo. As his condition worsened, his health failed, and he died there late in the evening on February 15 from complications related to an abscess that had developed in his brain. He was subsequently laid to rest on the parade grounds at Fort Jefferson.

In a follow-up report, Post Surgeon Jacob H. Scheetz, M.D., the 47th Pennsylvania’s assistant regimental surgeon, provided these details of the battle wound and treatment that Frederick had endured:

Private Edward Frederick, Co. K, 47th Pennsylvania Vols, was struck by a musket ball at the battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina, October 22, 1862. The ball lodged in the frontal bone and was removed. The wound did well for three weeks when he had a slight attack of erysipelas, which, however, soon subsided under treatment. The wound commenced suppurating freely and small spiculae of bone came away, or were removed, on several occasions. Cephalgia was a constant subject of complaint, which was described as a dull aching sensation. The wound had entirely closed on January 1, 1863, and little complaint made except the pain in the head when he exposed himself to the sun. About the 4th of February he was ordered into the hospital with the following symptoms: headache, pain in back and limbs, anorexia, tongue coated with a heavy white coating, bowels torpid. He had alternate flashes of heat; his pupils slightly dilated; his pulse 75, and of moderate volume. He was blistered on the nape of the neck, and had a cathartic given him, which produced a small passage. Growing prostrate, he was put upon the use of tonics, and opiates at night to promote sleep; without any advantage, however. His mind was clear til [sic] thirty-six hours before death, when his pupils were very much dilated, and he gradually sank into a comatose state until 12 M. [midnight] on the night of the 15th of February when he expired.

Another twelve hours after death: Upon removing the calvarium the membranes of the brain presented no abnormal appearance, except slight congestion immediately beneath the part struck. A slight osseus deposition had taken place in the same vicinity. Upon cutting into the left cerebrum, (anterior lobe) it was found normal, but an incision into the left anterior lobe was followed by a copious discharge of dark colored and very offensive pus, and was lined by a yellowish white membrane which was readily broken up by the fingers. I would also have stated that his inferior extremities were, during the last four days, partially paralyzed.

Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, circa 1861 (public domain).

As Private Frederick’s body was being autopsied, the unceasing routine of fort life continued as members of the regiment went about performing their duties and the USS Cosmopolitan arrived with a new group of prisoners. On February 25, 1863, Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander issued Special Order No. 17:

I. Company commanders are hereby ordered to instruct the chief of detachment in their respective companies to see that all embrasures in the lower tier, both at and between their batteries, are properly closed and bolted immediately after retreat.

II. As the safety of the garrison depends on the carrying out of the above order, they will hold chiefs of detachments accountable for all delinquencies.

In addition, orders were given to company cooks to relocate their operations to bastion C of the fort, which was a much cooler place for them to do their duties—a change that was likely appreciated as much or more by the under-cooks as the higher-ranking cooks who oversaw their grueling work.

This was the first of several initiatives undertaken by Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander who, according to Schmidt, “was having some difficulty in exercising proper control over Fort Jefferson as it related to the Engineering Department and persons in their employ.”

It was his duty to train the garrison, guard the prisoners, and provide the necessary protection for the fort and its environs, a situation fraught with many problems not always understood by other military and non-military personnel on station there. It was during this period that relationships between the various interests began to deteriorate, as overseer George Phillips, temporarily filling in for Engineer Frost, refused the request of Lt. Col. Alexander to have as many engineer workmen removed from the casemates as could be comfortably accommodated inside the barracks outside the walls of the fort. Phillips lost the argument and the quarters were vacated, but the tone of the several letters exchanged between the two commands left much to be desired. Differences were aired concerning occupations of the prisoners and their possible use by the engineers; the amount of water used by the workmen as Alexander limited them to one gallon per day per man; Engineer Frost arriving and reclaiming for his department the central Kitchen, and another kitchen near it that had been used by Capt. Woodruff and others; stagnant water in the ditches which involved the post surgeon [Jacob H. Scheetz, M.D.] in the controversy; uncovering of the ‘cistern trap holes’ located in the floors of the first or lower tier, which allowed the water supplies to become contaminated; who exercised jurisdiction over the schooner Tortugas of the Engineering Department; depredations of wood belonging to the engineers; and many other conflicts….

Around this same time, Corporal George Nichols, who had piloted the Confederate steamer, the Governor Milton, behind Union lines after it had been captured by members of the 47th’s Companies E and K in October, was assigned once again to engineering duties—this time at Fort Jefferson—but he was not happy about it, according to a letter he wrote to family and friends:

So I am detailed on Special duty again as Engineer. I cannot See in this I did not Enlist as an Engineer. But I get Extra Pay for it but I do not like it. So I must get the condencer redy [sic, condenser ready] to condece [sic, condense] fresh water. Get her redy [ready] and no tools to do it with.

Corporal Nichols’ reassignment was made possible when the contingent of 47th Pennsylvanians at Fort Jefferson was strengthened with the transfer there of members of Companies E and G from Fort Taylor on February 28. That same day, the men of F Company received additional training with both light and heavy artillery at the fort while the men from K Company gained more direct experience with the installation’s seacoast guns. In addition, members of the regiment finally received the six months of back pay they were owed.

Rev. William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock, chaplain, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, 1863 (courtesy of Robert Champlin, used with permission).

It was also during this latest phase of duty that Regimental Chaplain William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock was transferred from Fort Taylor to Fort Jefferson—possibly to render spiritual comfort after what had been a brutal month in terms of hospitalizations. Among the seventy members of the 47th Pennsylvania who had been admitted to the post’s hospital in the Dry Tortugas were fifty-four men with dysentery and/or diarrhea, four men with remittent or bilious remittent fevers, three men suffering from catarrh, one man who had contracted typhoid fever, one man who had contracted tuberculosis and was suffering from the resulting wasting away syndrome known as phthisis, and three men suffering from diseases of the eye (two with nyctalopia, also known as night blindness, and one with cataracts).

One of the additional challenges faced by the men stationed in the Dry Tortugas (albeit a less serious one) was that there was no camp sutler available to them at Fort Jefferson, as there was for the 47th Pennsylvanians who were stationed at Fort Taylor. So, it was more difficult, if not impossible, to obtain their favorite foods, replacements for worn-out clothing, tobacco, and other items not furnished by the quartermasters of the Union Army—making their lives more miserable with each passing day as they depleted the care packages that had been sent to them by their families during the holidays.

Stationed farther from home than they had ever been, they could see no end in sight for the devastating war that had torn their nation apart.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War: ‘Supplier of the Confederacy.’” Tampa, Florida: Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida, retrieved online January 15, 2020.

- Holder, Emily. “At the Dry Tortugas During the War.” San Francisco, California: Californian Illustrated Magazine, 1892 (part four, retrieved online, March 28, 2024, courtesy of Lit2Go, the website of the Educational Technology Clearinghouse at the Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida).

- “History: Crops (Historic Florida Barge Canal Trail).” Historical Marker Database, retrieved online December 30, 2023.

- Malcom, Corey. “Emancipation at Key West,” in “The 20th of May: The History and Heritage of Florida’s Emancipation Day Digital History Project.” St. Petersburg, Florida: Florida Humanities, retrieved online March 28, 2024.

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence, and Harriet Fason Chappell. King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign Relations of the Confederate States of America. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1959.

- “Preventing Diplomatic Recognition of the Confederacy, 1861–1865,” and “The Alabama Claims, 1862–1872,” in “Milestones: 1861–1865.” Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, United States Department of State, retrieved online December 30, 2023.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Staubach, Lieutenant Colonel James C. “Miami During the Civil War: 1861-65,” in Tequesta: The Journal of the Historical Association of Southern Florida, vol. LIII, pp. 31-62. Miami, Florida: Historical Museum of Southern Florida, 1993.

- Wharton, Henry D. Letters from the Sunbury Guards. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1861-1868.

You must be logged in to post a comment.