During the mid-1800s, the Kingdom of Bavaria was a mixture of rural natural areas and prosperous cities, including Nuremberg, an endpoint of the first railroad line built in Germany. (Street scene, Nuremberg, Germany, 1860, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As a native of one of the member states of the German Confederation, Nicholas Hoffman was born during the reign of King Ludwig I of Bavaria, a monarch who ushered in a period of history in which art and music flourished and modernization through industrialization was encouraged. As a child, he spent his formative years during a period in which German states formed the Zollverein economic union in which a group of German states banded together to adopt a uniform code for road tolls and tariffs to regulate trade fairly among the member states. Bavarian leaders also oversaw the construction of the Ludwig Canal and Germany’s first railroad during this period.

A diverse state, culturally and geographically, Bavaria was a mixture of small towns, very rural areas that featured spectacular views of pristine lakes and soaring mountains, and bustling cities that developed into major European centers of commerce with some of the most beautiful architecture in the world.

But, as happened within so many other German states during this era, a spirit of discontent was kindled in the hearts of residents as taxes were raised on average working people who were trying hard to eke out their existence. In response, their unelected rulers began to restrict political speech and other freedoms, which only fueled their subjects’ frustration and anger. In short order, that anger flared into the fires of German Revolution during the 1840s and inspired the mass emigration of Germans to America, which began in 1848.

Against this backdrop of fear and uncertainty, Nicholas Hoffman decided to leave all he knew behind in order to make his way across the ocean and settle in northeastern Pennsylvania while still in his early to mid-twenties. Hoping his new, permanent homeland would be a land of peace and opportunity, he arrived in the United States just as it was devolving into the same types of political, religious and social upheaval he had hoped to put behind him.

Formative Years

Delaware and Lehigh Rivers at Easton, Pennsylvania, 1844 (Augustus Kollner, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Born in the Kingdom of Bavaria circa 1830, Nicholas Hoffman emigrated to the United States sometime during the mid-nineteenth century. Church records show that he married Elizabeth Goodyear (alternate spellings: Goodear, Guthyear, Guth) in Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania on 9 May 1855 at St. Joseph’s Catholic Church.

* Note: A native of Pennsylvania who was born circa 1836, Elizabeth was known to family and friends as “Eliza,” and was a daughter of Francis Goodyear, a shoemaker, and his wife, Margaret (Fox) Goodyear (1818-1878), both of whom were natives of Germany. Eliza Goodyear’s siblings were: Lewis Goodyear (1833-1899), who was born on 1 September 1833; Clemens Goodyear (1834-1866; alternate birth year: 1845), who was born on 23 May 1834 and who later served with Nicholas Hoffman in the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry during the American Civil War; Francis Goodyear (alternate surname spelling: “Goodear”), who was born circa 1838 and who later served as the guardian of Nicholas Hoffman’s children after the American Civil War; Joseph Goodyear (1841-1865), who was born circa 1841 and also later served with Nicholas Hoffman in the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers; Margaret Goodyear, who was born circa 1842; Catharine Goodyear, who was born circa 1844; and Silvester Goodyear, who was born circa 1849.

Within two years, Nicholas Hoffman and his wife, Elizabeth, had begun building their own family in Easton. A daughter, Margaret Sophia, was born there on 23 October 1857 and baptized just over three weeks later, on 15 November 1857. Two years later, they greeted the arrival of daughter Elizabeth, who was born on 3 November 1859 and baptized on 20 November 1859.

Residing in the Borough of South Easton in 1860, according to that year’s federal census, the Hoffman family’s new decade together would be one of promise with the births of two more children: a son, John (1861-1865), who was born on 11 November 1861 and baptized on 29 November 1861; and another daughter, Catharine, who was born on 7 October 1863 and baptized on 25 October 1863.

Sadly, though, that new decade would also prove to be one of heartache.

Civil War

View of Easton (from Phillipsburg Rock, circa 1860-1862, James Fuller Queen, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

During the first years of the American Civil War, Nicholas Hoffman worked hard as a blue-collar laborer in Easton, doing all he could to keep a roof over the heads of his wife and children while watching friends and neighbors march off to a war they all hoped would end quickly. But by early 1864, when that war showed no signs of ending, he faced increasing peer pressure to join the fight.

Recruited by Captain Samuel Yohe, Nicholas Hoffman was subsequently enrolled in Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania on 15 February 1864, and was officially mustered in as a private with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry’s Company A that same day.

* Note: Captain Samuel Yohe had been appointed as a district provost marshal in northeastern Pennsylvania and placed in charge of Union Army recruitment efforts and other civil governance functions, after having commanded the 1st Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry during the American Civil War’s opening months.

Military records at the time noted that Private Nicholas Hoffman was a thirty-four-year-old native of Bayern [Bavaria] who was employed in Easton as a laborer. Five feet, five-and-one-half-inches tall, he reportedly had sandy hair, brown eyes and a dark complexion.

Although did not know it at the time, he was joining the 47th Pennsylvania just as it was about to make history as the only regiment from Pennsylvania to participate in the Union’s 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana. His decision would ultimately prove to be a fatal one.

Red River Campaign

Transported via ship to America’s Deep South, Private Nicholas Hoffman connected with his regiment while it was preparing for its move from its duty stations at Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Florida to Louisiana. The men from every company, except Company A—to which Private Hoffman had been assigned—boarded ships on 28 February and 1 March 1864 and sailed away toward Algiers, Louisiana (now part of New Orleans), where they disembarked and boarded a train that was bound for Brashear City (now Morgan City, Louisiana). Disembarking from that train, they were then transported to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. Upon their arrival, they were assigned to the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the Department of the Gulf’s 19th Army Corps (XIX Corps), all of which fell under the campaign’s overall command of Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks.

Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the men from Company A awaited transport at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida to enable them to catch up with the main part of their regiment. Charged with guarding and overseeing the transport of two hundred and forty-five Confederate prisoners, they were finally able to board the Ohio Belle on 7 April.

But they had missed the two bloodiest combat engagements that their regiment would endure during the Red River Campaign—the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield on 8 April and the Battle of Pleasant Hill on 9 April. According to historian Lewis Schmidt, they were far away from the scene of those battles because they had been ordered to take the Confederate prisoners to New Orleans—a directive that extended their detached duty and kept them from rejoining the main regiment until they reached Alexandria, Louisiana on 27 April.

Christened “Bailey’s Dam” in reference to the Union officer who oversaw its construction, Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, this timber dam built by the Union Army on the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana in May 1864 facilitated Union gunboat passage (public domain).

This meant that Private Nicholas Hoffman and the other men from Company A also missed a third combat engagement—the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the Affair at Monett’s Ferry”), which took place on 23 April.

They were able to participate in their regiment’s next major engagement, however; from late April through mid-May, they helped to erect Bailey’s Dam on the Red River near Alexandria. In a letter penned from Morganza, Louisiana on 29 May, C Company Musician Henry Wharton described their mission and the weeks that followed:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gunboats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people, will eat) so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the ironclads down the river. After a great deal labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order the day before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits [sic] on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Continuing their march, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed toward Avoyelles Parish. According to Henry Wharton:

On Sunday, May 15, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad wherewith the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. – We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed in line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired and we advanced ‘till dark, when the forces halted for the night, with orders to rest on their arms. – ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

Having entered Avoyelles Parish, they “rested on their arms” for the night, half-dozing without pitching their tents, but with their rifles right beside them. They were now positioned just outside of Marksville, Louisiana on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, the infantry advanced in line until they reached Mousoula [sic, Mansura], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic, maneuvering] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain correctly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over. – The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of our army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Resuming their trek south, Private Nicholas Hoffman and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. As his longer-serving comrades had done during their tours of duty in the Carolinas and Florida, Private Hoffman had battled the elements, as well as the Confederate Army, in order to survive and continue to defend his nation. Sadly, he survived it all, only to be felled by his regiment’s most deadly foe—disease.

Illness and Death

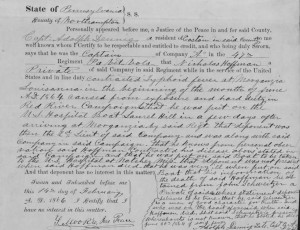

This 14 February 1866 attestation by Captain Adolph Dennig, Company A, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, confirmed that Privates Nicholas Hoffman and John Schweitzer were assigned to the Union’s hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, in June 1864, and documented Hoffman’s death from typhoid aboard that ship on 30 June 1864 (Elizabeth Hoffman’s U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension File, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

Sometime in early June, while still stationed with his regiment at the Union Army’s encampment near Morganza Bend, Louisiana, Private Nicholas Hoffman began to feel tired and uncomfortable. Suffering from aching joints, bouts of disabling diarrhea and an increasingly high fever, his condition worsened over the next several weeks. Ultimately diagnosed by regimental physicians with typhoid fever, he was ordered to board the USS Laurel Hill, a Union hospital ship that was preparing to transport wounded and sick soldiers to the Union’s General Hospital in Natchez, Mississippi. According to an affidavit filed, post-war, by 47th Pennsylvania Captain Adolph Dennig (who was a second lieutenant with Company A at the time that Private Hoffman fell ill):

Nicholas Hoffman—a Private of said Company in said Regiment [Company A, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry] while in the service of the United States and in line duty contracted Typhoid fever during the Red River Campaign La. in June 1864 and was put on the U. States Steamer Laurel Hill at Morganzia [sic, Morganza] La. on or about the 27th day of June 1864, and died of said illness while on said Steamer on his way to the U.S. General Hospital at Natches [sic, Natchez] Miss. on or about the 30th day of June 1864. That he was very ill when put on said Steamer. His disease originated from his, said Hoffman’s, unavoidable exposure in said Red River Campaign prior to which he was a healthy man.

Dennig added that Private Hoffman had not been dropped from the 47th Pennsylvania’s muster rolls until 22 February 1865. That muster roll change, made by regimental order, noted that Private Hoffman’s deletion from the muster rolls was due to Hoffman’s death.

Due to the highly contagious nature of his disease, and because the Laurel Hill was still in transit from Morganza to Natchez when he died, Private Nicholas Hoffman was most likely buried at sea, as had happened with several other 47th Pennsylvanians who had died aboard Union hospital ships during the war. A memorial has been created for Private Hoffman at Find A Grave in order to allow descendants to pay their respects to him.

* According to historian Lewis Schmidt, the remains of Private Nicholas Hoffman may rest somewhere on the grounds of the Natchez National Cemetery in Natchez, Mississippi. Schmidt based his theory on a separate affidavit that had been filed by Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant Charles H. Small who stated that Private Hoffman had been buried somewhere in Natchez. Schmidt also based his theory on the history of the initial burials and subsequent exhumation and reburial of Union soldiers at Natchez, which were deeply flawed by the mishandling of soldiers’ remains. Many of the interred/reinterred soldiers were simply marked as “Unknown” and remain unidentified because the records failed to precisely document who was buried in which cemetery plot.

What Happened to the Wife and Children of Nicholas Hoffman?

Attestation submitted on 4 November 1864 by Elizabeth (Goodyear) Hoffman as part of her U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension application, which documented her marriage to, and children with, Private Nicholas Hoffman, Company A, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (Elizabeth Hoffman’s U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension File, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain; click to enlarge).

Suddenly thrust into the role of a single parent with four young children, Nicholas Hoffman’s widow, Elizabeth, had little time to mourn the death of her soldier-husband. Battling to keep her children housed and fed, she applied for a U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension in late October to early November 1864—less than six months after her husband’s death. Completing her widow’s pension application paperwork with the help of her younger siblings, she also sought and obtained help from two of her sisters-in-law, Emeline (Steinmetz) Goodyear (1839-1915; alternate spelling “Goodear”), who was the wife of Elizabeth’s younger brother, Francis Goodyear, and Ellen (Azer) Goodyear (1842-1927), the wife of Elizabeth’s older brother, Lewis Goodyear. Both women submitted sworn testimony in which they affirmed Elizabeth’s marriage to Nicholas Hoffman, as well as the births of the children she had with him.

After filing her U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension application on 14 November 1864, Elizabeth (Goodyear) Hoffman waited for a response from the federal government—and waited. Finally, because the federal government’s review of her application was taking too long, and because she had four young children to care for, she found herself forced to look for support elsewhere—support that she ultimately found when she remarried on 1 June 1865 to Charles Grimm, a native of the Kingdom of Württemberg.

Just weeks later, U.S. Pension Bureau officials notified her that they were rejecting her application for support—an application that she had submitted in 1864 and had still not been approved. Those officials had denied her claim almost as soon as they had received word that she had remarried.

As if that were not disheartening enough, 1865 would prove to be an even more devastating year for Elizabeth (Goodyear) Hoffman Grimm for an entirely different reason—the death of her son, John Hoffman, who passed away at the age of five on 23 November 1865.

Slightly less than two years later, on 5 August 1867, Elizabeth (Goodyear) Hoffman’s younger brother, Francis Goodyear (alternate spelling “Goodear”), was appointed as guardian of Nicholas Hoffman’s remaining minor children and was given the authority to apply for, and then oversee on their behalf, the U.S. Civil War Minor Children’s Pension support that they had been awarded by the federal government. Known as “Frank” to his family and friends, Francis Goodyear was subsequently able to secure an initial pension of eight dollars per month on 21 March 1868, plus an additional two dollars per month for each of Nicholas Hoffman’s daughters (fourteen dollars per month, total). The start of the primary pension fund of eight dollars per month was made retroactive to the date of their father’s military service-related death (30 June 1864); the start of the supplemental funds of two dollars per child per month was made retroactive to 25 July 1866.

Goodyear then oversaw the distribution of those pension funds to their respective terminations (on the dates before each child turned sixteen). Those terminations occurred for Margaret Sophia on 22 October 1873, for Elizabeth on 2 November 1874 and for Catharine on 6 October 1879.

By 1880, Nicholas Hoffman’s widow, Elizabeth (Goodyear Hoffman) Grimm was documented by a federal census enumerator as a resident of the Borough of South Easton. She lived there with her second husband, Charles Grimm, and their children, Mary Grimm, who was born circa 1876, and Agnes Grimm, who was born circa 1877. Also residing with them were Elizabeth’s children from her first marriage—Margaret and Elizabeth—both of whom had adopted the surname of “Grimm.”

Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have not yet determined what happened Elizabeth (Goodyear Hoffman) Grimm and her children after 1880 but continue to search for information about their lives and burial locations. If you would like to support this research, please consider making a donation to our project by using the secure donations page on our website.

* To view more of the key U.S. Civil War Pension records related to the Hoffman, Goodyear and Grimm families, visit our Hoffman-Goodyear-Grimm Family Collection.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Captain Samuel Yohe (death notice), in “City Notes.” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Philadelphia Times, 8 July 1880.

- Goodyear, Francis (father), Margaret (mother), Lewis, Eliza (future wife of Nicholas Hoffman), Francis (son of Francis Goodyear and future guardian of the children of Nicholas Hoffman and Eliza Goodyear Hoffman), Joseph (future member of Co. A, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry), Margaret (daughter), Catharine, Clemens (future member of Co. A, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry), and Silvester, in U.S. Census (Chestnuthill Township, Monroe County, Pennsylvania, 1850). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Grimm, Charles, Elizabeth (Nicholas Hoffman’s remarried widow), Margaret (Nicholas Hoffman’s daughter), Elizabeth (Nicholas Hoffman’s daughter), Mary (daughter of Charles Grimm and Elizabeth Goodyear Hoffman Grimm), and Agnes (daughter of Charles Grimm and Elizabeth Goodyear Hoffman Grimm), in U.S. Census (Borough of South Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Hoffman, Nicholas, in Civil War Muster Rolls (Co. A, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Hoffman, Nicholas, in Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (Co. A, 47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Hoffman, Nicholas and Elizabeth, in U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Cards (widow’s application no.: 71937, filed by the widow on 14 November 1864; child guardian’s application no.: 150955, certificate no.: 110375, filed by the child’s guardian, Francis Goodyear, on 8 August 1867). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Hoffman, Nicholas, Elizabeth (mother), Margaret, and Elizabeth (daughter), in U.S. Census (Borough of South Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, 1860). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Hoffman, Nicholas and Goodyear, Clemens and Joseph, in “Registers of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5 (Company A, 47th Regiment),” in “Records of the Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs” (RG-19). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Mahr, Michael. “Typhoid Fever – One of the Civil War’s Deadliest Diseases.” Frederick, Maryland: National Museum of Civil War Medicine, 1 July 2021.

- “Mrs. Emma Goodear” (obituary of Elizabeth Goodyear Hoffman’s sister-in-law). Easton, Pennsylvania: Easton Express, 20 March 1915.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- Wharton, Henry D. Letters from the Sunbury Guards, 1861-1868. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American.

You must be logged in to post a comment.