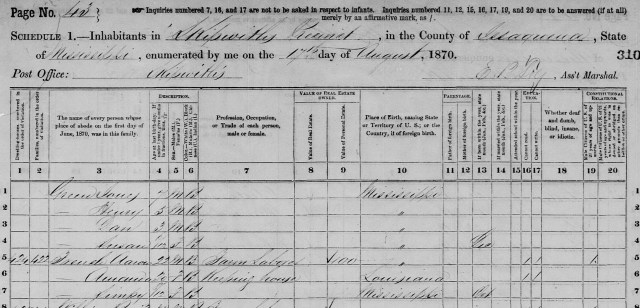

Personal Letter from Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, Commanding Officer of Company C, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (14 December 1862)

Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, Company C, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (circa 1862, public domain).

Beaufort, So. Ca.

December 14, 1862

Dear Friends,

This is the last letter you will receive from me dated as above. For some time, our Regt. has been ordered to Key West again and we leave for there tomorrow. We are even now all packed up and I am writing amid the piles of rubbish accumulated in a five months residence in Camp. Gen. Brannen [sic] expects to go North and his object evidently is to get us out of this Department so that when he is established in his command, he can get us with him. If we remained here Gen Hunter would not let us go as he is as well aware as is Brannen [sic] is that we are the best Regiment in the Department. Although I do not like the idea of going back there, under the circumstances we are content. At all events we will have nice quarters easy times, and plenty of food. But for my part I would rather have some fighting to do. Since we have become initiated I rather like it. At Key West we will get none, and have a nice rest after our duties here. I will take all my men along – not being compelled to leave any behind. Direct my letters hereafter to Key West, Fla.

I supposed the body of Sergt Haupt has arrived at home long ere this. When we left Key West [Last?] Oyster & myself bought a large quantity of shells, and sent them to Mrs Oyster. If we got home all right [sic] Haupt was to make boxes for us. He having died, you and Mrs Oyster divide the shells, and you can take [two illegible words] and give them to our friends. Some to Uncle Luther [sp?], Jacob Lawk [sp?], Louisa Shindel and all friends. I can send some more when we get to Key West if they want them.

Arrangements are being made to run a schooner regularly between here and Key West, so your boxes sent to us will follow us. Neither Mrs Wilsons nor yours has been received yet.

I think I will send a box home from here containing a few articles picked up at St. John’s Bluff and here. They examine all boxes closely but I think I can get some few articles through. The powder horn bullet pouch and breech sight I got at St. John’s Bluff the rest here. I will write, as soon as we get to Key West. Let me hear from you often. With love to all I remain

Yours,

J. P. Shindel Gobin

P.S. Get Youngman & [illegible name] to publish the change of your address.

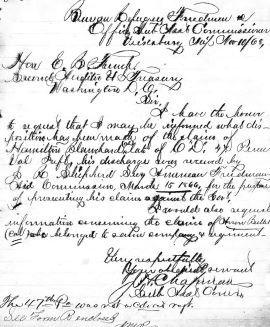

Letter to the Sunbury American Newspaper from Henry D. Wharton, Musician, Company C, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (published 10 January 1863)

USS Seminole and USS Ellen accompanied by transports (left to right: Belvidere, McClellan, Boston, Delaware, and Cosmpolitan) at Wassau Sound, Georgia (circa January 1862, Harper’s Weekly, public domain).

[Correspondence for the AMERICAN.]

Letter from the Sunbury Guards,

FORT TAYLOR, KEY WEST, Florida. }

December 21, 1862.

DEAR WILVERT:– Again at Key West. On Monday, December 15th we left Beaufort, S.C., on board the Steamer Cosmopolitan and proceeded to Hilton Head, where Gen. Brannen [sic] came on board to bid farewell to his regiment. Capt. Gobin addressed him in a neat little speech, which the General tried to reply to, but his feelings were too full and tears were in his eye as he bid the old word, ‘Good Bye.’ The boys gave him tremendous cheers as he left the vessel and the Band discoursed sweet music ‘till he reached the shore. The members of our regiment felt badly on leaving his command; but the assurance that we will soon be with him, in another department, makes them in a better humor; for with him they know all their wants are cared for, and in battle they have a leader on whom they can depend.

On the passage down, we ran along almost the whole coast of Florida. Rather a dangerous ground, and the reefs are no playthings. We were jarred considerably by running on one, and not liking the sensation our course was altered for the Gulf Stream. We had heavy sea all the time. I had often heard of ‘waves as big as a house,’ and thought it was a sailor’s yarn, but I have seen ‘em and am perfectly satisfied; so now, not having a nautical turn of mind, I prefer our movements being done on terra firma, and leave old neptune to those who have more desire for his better acquaintance. A nearer chance of a shipwreck never took place than ours, and it was only through Providence that we were saved. The Cosmopolitan is a good river boat, but to send her to sea, loadened [sic] with U.S. troops is a shame, and looks as though those in authority wish to get clear of soldiers in another way than that of battle. There was some sea sickness on our passage; several of the boys ‘casting up their accounts’ on the wrong side of the ledger.

Fort Jefferson, Dry Torguas, Florida (interior, c.irca 1934, C.E. Peterson, photographer, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

We landed here on last Thursday at noon, and immediately marched to quarters. Company I. and C., in Fort Taylor, E. and B. in the old Barracks, and A. and G. in the new Barracks. Lieut. Col. Alexander, with the other four companies proceeded to Tortugas, Col. Good having command of all the forces in and around Key West. Our regiment relieves the 90th Regiment N.Y.S. Vols. Col. Joseph Morgan, who will proceed to Hilton Head to report to the General commanding. His actions have been severely criticized by the people, but, as it is in bad taste to say anything against ones superiors, I merely mention, judging from the expression of the citizens, they were very glad of the return of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

The U.S. Gunboat ‘Sagamore’ has had good luck lately. She returned from a cruise on the 16th inst., having captured the English sloop ‘Ellen’ and schooners ‘Agnes,’ ‘By George’ and ‘Alicia,’ all hailing from Nassau N.P. The two former were cut out in India river by a boat expedition from the Sagamore. They had, however, previously discharged their cargoes, consisting principally of salt, and were awaiting a return cargo of the staple, (cotton) when the boats relieved them from further trouble and anxiety. The ‘By George’ was sighted on the morning of the 1st, and after a short chase she was overhauled. Her Captain, in answer to ‘where bound!’ replied Key West, but being so much out of his course and rather deficient in the required papers, an officer was placed in charge in order that she might safely reach this port. Cargo – Coffee, Salt, Medicines, &c. The “Alicia,’ cotton loaded, was taken in Indian river inlet, where she was nicely stowed away waiting a clear coast. The boats of the Sagamore also destroyed two small sloops. They were used in Indian river, near Daplin, by the rebels in lightering cargoes up and down the river. There are about twenty more prizes lying here, but I was unable to get the names of more than the following:

Schooner ‘Dianah.’ assorted cargo.

“ ‘Maria.’ “ “

“ ‘Corse.’ “ “

“ ‘Velocity.’ “ “

“ ‘W.E. Chester.’ sixty bales of cotton.

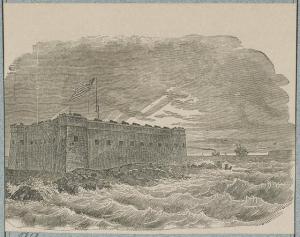

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Key West has improved very little since we left last June, but there is one improvement for which the 90th New York deserve a great deal of praise, and that is the beautifying of the ‘home’ of dec’d. soldiers. A neat and strong wall of stone encloses the yard, the ground is laid off in squares, all the graves are flat and are nicely put in proper shape by boards eight or ten inches high on the ends sides, covered with white sand, while a head and foot board, with the full name, company and regiment, marks the last resting place of the patriot who sacrificed himself for his country.

Two regiments of Gen. Bank’s [sic] expedition are now at this place, the vessels, on which they had taken passage for Ship Island, being disabled, they were obliged to disembark, and are now waiting transportation. They are the 156th and 160th N.Y.S. Vols. Part of the 156th are with us in Fort Taylor.

Key West is very healthy; the yellow fever having done its work, the people are very much relieved of its departure. The boys of our company are all well. I will write to you again as soon as ‘something turns up.’ With respects to friends generally, I remain,

Yours, Fraternally,

H. D. W.

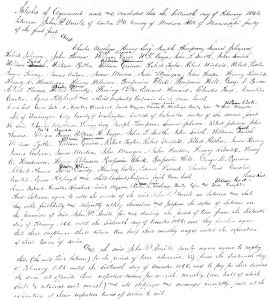

Excerpts of Diary Entries from Henry Jacob Hornbeck, Private, Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (December 1863 and Early January 1864)

Key West, Florida (circa 1850, courtesy of the Florida Memory Project).

December 1863. The workers at the fortification in Key West demanded back pay and a raise in December; their rate was $1.40 per day. The town had some excitement in December as a spark from a railway locomotive set the mess hall on fire, burning it to the ground; and nature retaliated with a violent storm, which caused heavy damage, putting the railroad out of service.

Friday December 25th. …. rose at 3 a.m. & proceeded to Slaughter House, had two Cattle & two Sheep cut up and served to the troops. Conveyed Fresh Meat to a number of citizens this morning, being Gen’l Woodburys [sic] gift, then had breakfast. Went to Fort Stables, had the horse fed, visited Mrs. Abbot in Fort Taylor, also Mrs. Heebner, from both of whom we rec’d Christmas Cakes & a drink, which were excellent…. We took dinner at Capt. Bells at 2 p.m. which was a splendid affair. A fine turkey served up, and finished up our dinner with excellent Mince pie, after the dinner we again took a ride about the Island, took the horse to Fort Stables and returned to office. At 5 p.m. a party of Masqueraders (or what we term in our State Fantasticals) paraded the street headed with music, a very comical party. Took a walk tonight, Churches finely decorated. Retired early at ½ past 8 p.m. Weather beautiful….

1864

January 1st Thursday. Rose as usual. After breakfast, went to office, kept busy all day on account of many steamers lying in port, waiting to coal. After supper took a walk about the city with Frank Good and Wm. Steckel. Heard music in a side street, went there and found the Black Band playing at the Postmaster’s residence. The Postmaster then called all the soldiers in, and gave us each a glass of wine.

He is a very patriotic man and very generous. I believe his name is Mr. Albury. We then went to barracks and retired.

January 2nd Friday…. After breakfast, work as usual in office. After dinner took a horseback ride to Fort Taylor…. Retired at 9 o’clock. Weather cool.

January 3rd Saturday…. Received our extra duty pay this afternoon. Purchased toilet articles. After supper went to the camp, took a walk about city, then went barracks & retired. Latest reports are that Burnside was defeated with great loss and the Cabinet broke up in a row. Retired at 10. Weather fine.

Sunday January 4th…. After breakfast, washed & dressed. After dinner John Lawall, Wm. Ginkinger & myself went to the wharf. I then returned to barracks and P. Pernd. E. Crader and myself went out on the beach, searching sea shell. Returned by 4 o’clock. I then cleaned my rifle. Witnessed dress parade. Then went to supper. After supper went to the Methodist Church, heard a good Sermon by our Chaplain. Retired at 9 o’clock.

Monday January 5th…. After breakfast went to office, busy, wrote a letter to Reuben Leisenring. At 11 o’clock the U.S. Mail Steamer Bio arrived from New York, having come in 5 days, papers dating 30th inst. The reports of a few days ago, are not confirmed, therefore they are untrue. She also has a mail on board.

Tuesday January 6th…. Received no letter yesterday, very small mail for our regiment. Busy all day in office. After supper, Wm. Smith, Allen Wolf & myself took a walk about the city, then went to barracks. Retired at 10 o’clock. Wrote a letter this afternoon to Uncle Ebenezer, sent him also by mail a small collection of sea shells. Weather fine.

Sources:

- Gobin, John Peter Shindel. Personal Letters, 1861-1865. Northumberland, Pennsylvania: Personal Collection of John Deppen.

- Hornbeck, Henry Jacob. Diary Excerpts, 1862-1864, in 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story. Retrieved online 1 December 2017.

- Wharton, Henry D. Letters from the Sunbury Guards. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1861-1868.

You must be logged in to post a comment.