“Labor Is Life” (U.S. Postal Service’s Labor Day Stamp, 1956, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Bakers, blacksmiths, boatmen, butchers, carpenters, cabinetmakers, cigarmakers, coal miners, factory workers, farmers, gardeners, gold miners, iron workers, masons, quarry workers, teamsters, tombstone carvers. These were just a few of the diverse job titles held by the laborers who enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry during the American Civil War.

Many returned to their same occupations after the war ended while others found new pathways for their life journeys. Far too many were never able to return to the arms of their loved ones and still rest in marked or unmarked graves far from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

In honor of Labor Day, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story is proud to present this abridged list of blue-collar men and boys who served with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry between August 1861 and January 1866, as well as the names of two of the women associated with the regiment who made their own unforgettable marks on the world.

* Auchmuty, Samuel S. (First Lieutenant, Company D): A native of Duncannon, Perry County and veteran of the Mexican-American War who was employed as a carpenter during the early 1860s, Samuel Auchmuty responded to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to defend the nation’s capital during the opening weeks of the American Civil War by enrolling as a first lieutenant with Company D of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on August 20, 1861; after completing his three-year term of enlistment, he was honorably discharged in September 1864 and returned home to Pennsylvania, where he resumed his work as a house carpenter and launched a successful contracting business that was responsible for building new business structures, churches, single-family homes, and schools, as well as renovating existing structures; he died in 1891, following a brief illness;

* Beard, Christian Seiler (First Lieutenant, Company C): A twenty-seven-year-old, married carpenter residing in Williamsport, Lycoming County when President Abraham Lincoln called for seventy-five thousand volunteers to defend the nation’s capital, following the fall of Fort Sumter in mid-April 1865, Chistian S. Beard promptly enrolled for Civil War military service before that month was out as a private with Company D of the 11th Pennsylvania Volunteers; honorably discharged in July after completing his Three Months’ Service, he re-enlisted as a sergeant with Company C of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers on August 19; after rising up through the ranks to become a first lieutenant, he was honorably discharged on Christmas Day, 1865, and returned home to his wife in Dauphin County, Pennsylvania, where he continued to work as a carpenter; after having several children with his wife, he was widowed by her; remarried in 1884, he relocated with his wife and children to Pittsburgh, where he continued to work as a carpenter; ailing with heart and kidney disease, he died there on November 16, 1911 and was interred at that city’s Highwood Cemetery;

* Burke, Thomas (Sergeant, Company I): A first-generation American, Thomas Burke was a twenty-year-old cabinetmaker residing in Allentown at the dawn of the American Civil War; after enrolling for military service on the day that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was founded (August 5, 1861), he was officially mustered in as a private; from that point on, he continued to work his way up the ranks, receiving a promotion to corporal on September 19, 1864 and then to sergeant on July 11, 1865; honorably mustered out with his company in Charleston, South Carolina on December 25, 1865, he returned home to Lehigh County, where he married and began a family; sometime in early to mid-1871, he and his family migrated west to Iowa, settling in Anamosa, Jones County, where he was employed as a carpenter and contractor; he died at his home there on October 22, 1910 and was buried at that town’s Riverside Cemetery;

* Colvin, John Dorrance (Second Lieutenant, Company C): A native of Abington Township, Lackawanna County who was a farmer when he enlisted for Civil War military service on September 12, 1861, John D. Colvin transferred to the U.S. Army Signal Corps on October 13, 1863, and continued to serve with the Signal Corps for the duration of the war; employed as an engineer, post-war, he helped the Pacific Railroad to extend its service from Atchison, Kansas to Fort Kearney in Nebraska before returning home to Pennsylvania, where he married, began a family and resided with them in Olyphant and Carbondale before relocating with them to Parsons in Luzerne County, where he became a prominent civic leader and member of the school board; initially employed as a machinist, he went on to become superintendent of the Delaware & Hudson Coal company before taking a similar job with the Lehigh Valley Coal Company; the U.S. Postal Service’s postmaster of Parsons during the early 1890s, he died there on March 15, 1901 and was buried at the Hollenback Cemetery in Wilkes-Barre;

* Crownover, James (Sergeant, Company D): A twenty-three-year-old teamster residing in Blain, Perry County when he enrolled for Civil War military service on August 20, 1861, James Crownover rose up through the ranks of the 47th Pennsylvania from private to reach the rank of sergeant; wounded in the right shoulder and captured by Confederate troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, he was marched to Camp Ford, near Tyler, Texas, the largest Confederate prison camp west of the Mississippi River, where he was held as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on November 25, 1864; during captivity, he was commissioned, but not mustered as a second lieutenant; given medical treatment before he was returned to active duty, he was honorably discharged with his regiment in Charleston, South Carolina on December 25, 1865; after returning home, he found work at a tannery near Blain, married, began a family and then relocated with them to East Huntingdon Township, Westmoreland County, where he worked as a teamster; relocating with them to Braddock in Allegheny County after the turn of the century, he worked at a local mill there; he died in Allegheny County on July 18, 1903 and was buried at the Monongahela Cemetery in Braddock Hills;

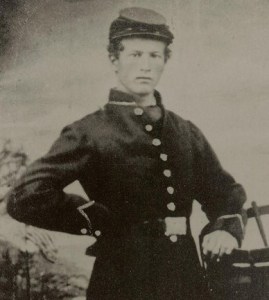

Jacob Daub, circa 1862-1865 (carte de visite, Cooley & Beckett Photographers, Savannah, Georgia and Beaufort and Hilton Head, South Carolina, public domain).

* Daub, Jacob and William J. (Drummer Boy, Company A): A German immigrant as a child, Jacob Daub emigrated with his parents and younger brother, William, circa 1852; after settling in Easton, Northampton County, Pennsylvania, where his father found work as a stone mason, Jacob grew up to become a cigarmaker, and also became the first of the two brothers to enlist in the American Civil War; after enrolling at the age of sixteen, he was classified as a field musician and assigned to Company A as its drummer boy; his nineteen-year-old brother, William, a carpenter by 1865, followed him into the war when he enlisted as a private with the same company in February of that year; after the war ended, both returned home to Northampton County, where they married, had children and went on to live long, full lives; William eventually died at the age of eighty in 1928, followed by Jacob, who passed away in 1936, roughly two months before his ninety-first birthday;

* Detweiler, Charles C. (Private, Company A): Berks County native Charles Detweiler enrolled for Civil War military service on September 16, 1862; a carpenter who later became a farmer, he served with Company A until he was severely injured in the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, October 19, 1864, when he sustained a musket ball wound to the middle of his thigh; treated at a Union Army hospital in Virginia before being transported to the Union’s Mower General Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, he learned that the musket ball had damaged his femur and femoral arteries; following his wound-related death at Mower on March 12, 1865, he was buried at the Fairview Cemetery in Kutztown, Berks County;

* Diaz, John (Private, Company I): An immigrant from Spain’s Canary Islands, John Diaz emigrated sometime between 1862 and 1865 and settled in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, where he found work as a cigarmaker; on January 25, 1865, at the age of nineteen, he enlisted with the Union Army at a recruiting depot in Norristown, Montgomery County and served as a private with Company I of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry until it was mustered out on Christmas Day, 1865; following his return to Pennsylvania, he resumed work as a cigarmaker in Philadelphia, eventually launching his own cigarmaking firm, which became a family business as his sons became old enough to work for him; sometime between 1906 and 1910, he relocated with his wife and several of his children to Camden County, New Jersey, where he died on September 5, 1915;

* Downs, James (Corporal, Company D): A twenty-three-year-old tanner residing in Blain, Perry County when he enrolled for Civil War military service on August 20, 1861, James Downs was captured by Confederate troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864 and marched to Camp Ford, near Tyler, Texas, the largest Confederate prison camp west of the Mississippi River; held there as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864, he received medical treatment and was subsequently returned to active duty; following his honorable discharge with his regiment in Charleston, South Carolina, on December 25, 1865, he returned home, married, began a family and relocated with his family to Phillipsburg, New Jersey; suffering from heart and kidney disease, and possibly also from post-traumatic stress disorder, rather than “insane” as physicians at the Pennsylvania Memorial Home in Brookville, Jefferson County, Pennsylvania had diagnosed him, he fell from a window at that home and died at there on September 16, 1921; he was subsequently interred in the Veterans’ Circle of the Brookville Cemetery;

* Eagle, Augustus (Second Lieutenant, Company F): A German immigrant as a teenager, Augustus Eagle arrived in America on June 23, 1855, two years after his brother, Frederick Eagle, had emigrated and made a life for himself in Catasauqua, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania; both men married and began families there, with Fred employed as a laborer and Gus employed by the Crane Iron Works; when President Abraham Lincoln issued his call for volunteers to defend the nation’s capital during the opening weeks of the American Civil War, both men enrolled for military service on August 21, 1861 as privates with Company F of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; in 1862, Fred fell ill and was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability, but Gus continued to serve, rising up through the regiment’s enlisted and officers’ ranks; commissioned as a second lieutenant, he was honorably discharged on September 11, 1864, upon completion of his three-year term of service; post-war, Fred became a successful baker with real estate and personal property valued at $4,200 (roughly $155,750 in 2023 dollars) and died in Catasauqua in 1885, while Gus owned a successful restaurant in Whitehall Township before operating the Fairview Hotel, which became a popular spot for political gatherings; after suffering a series of strokes in 1902, Gus died at his home on August 17 and was buried at the Fairview Cemetery in West Catasauqua;

* Eisenbraun, Alfred (Drummer Boy, Company B): A tobacco stripper and first-generation American from Allentown, Lehigh County, fifteen-year-old Alfred Eisenbraun became the second “man” from the 47th Pennsylvania to die when he succumbed to complications from typhoid fever at the Kalorama Eruptive Fever Hospital in Georgetown, District of Columbia on October 26, 1861; he still rests at the U.S. Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home Cemetery in Washington, D.C.;

* Fink, Aaron (Corporal, Company B): A shoemaker and native of Salisbury Township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, Aaron Fink, grew up, began a family and established a successful small shoemaking business, first in Allentown and then in Mauch Chunk (now Jim Thorpe) in Carbon County; on August 20, 1861, he chose to respond to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to help bring the American Civil War to a quick end when he enrolled for military service; shot in the right leg during the fighting at the Frampton Plantation during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862, he was treated at the Union Army’s hospital at Hilton Head, South Carolina, but died there from wound-related complications on November 5, 1862; initially buried near that hospital, his remains were later exhumed by Allentown undertaker Paul Balliet and returned to Pennsylvania for reinterment at that city’s Union-West End Cemetery;

* Fornwald, Reily M. (Corporal, Company G): Born in Heidelberg Township, Berks County, Reily Fornwald was raised there on his family’s farm near Stouchsberg; educated in his community’s common schools and then at Millersville State Normal School, he became a railroad worker before returning to farm life shortly before the dawn of the American Civil War; after enlisting for military service at the age of twenty on September 11, 1862, he was wounded in the head and groin by an exploding artillery shell during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862; stabilized on the battlefield before being transported to a field hospital for more advanced medical care, he spent four weeks recuperating before returning to active duty with his regiment; promoted to the rank of corporal on January 19, 1863, he continued to serve with his regiment until he was honorably discharged at Berryville, Virginia on September 18, 1864, upon expiration of his term of enlistment; after returning home, he spent four years operating a blast furnace for White & Ferguson in Robesonia, Berks County; he also married and began a family; sometime around 1870, he left that job to become an engine operator for Wright, Cook & Co. in Sheridan and then moved to a job as an engine operator for William M. Kauffman—a position he held for roughly a decade before securing employment as a shifting engineer with the Reading Railway Company at its yards in Reading; following his retirement in 1905, he and his wife settled in Robesonia, where he became involved in buying and selling real estate; following a severe fall in May 1925, during which he fractured a thigh bone, he died at the Homeopathic Hospital in Reading on June 1 and was buried at Robesonia’s Heidelberg Cemetery;

* Gardner, Reuben Shatto, John A. and Jacob S. R.: Natives of Perry County, Reuben Shatto Gardner and his brothers, John A. Gardner and Jacob S. R. Gardner, began their work lives as laborers; among the earliest responders to President Abraham Lincoln’s call to defend the nation’s capital, following the fall of Fort Sumter in mid-April 1861, Reuben was a twenty-five-year-old miller who resided in Newport, Perry County; after enlisting as a private with Company D of the 2nd Pennsylvania Volunteers on April 20, he was honorably mustered out after completing his term of service; he then re-upped for a three-year tour of duty, mustering in as a first sergeant with Company H of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; also enrolling with him that same day were his twenty-three-year-old and twenty-one-year-old brothers, John A. Gardner and Jacob S. R. Gardner; John officially mustered in at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg on September 18 (the day before Reuben arrived), while Jacob officially mustered in on September 19; both joined their brother’s company, entering at their respective ranks of corporal and private, but Jacob’s tenure was a short one; sickened by typhoid fever in late December 1861, he died at the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental hospital at Camp Griffin, near Langley, Virginia on January 8, 1862; his remains were later returned to Perry County for burial at the Old Newport Cemetery; soldiering on, Reuben and John were transported with their regiment by ship to Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida and subsequently sent to South Carolina with their regiment and other Union troops; shot in the head and thigh during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862, Reuben was treated at the Union Army’s hospital at Hilton Head, South Carolina for an extended period of time, and then returned to active duty with his regiment; meanwhile, John was assigned with H Company and the men from Companies D, F and K to garrison Fort Jefferson in Florida’s Dry Tortugas; both brothers then continued to work their way up the regiment’s ranks, with John promoted to corporal on September 18, 1864 and Reuben ultimately commissioned as a captain and given command of Company H on February 16, 1865; both then returned home after honorably mustering out with the regiment in Charleston, South Carolina on Christmas Day, 1865; sometime around 1866 or 1867, Reuben and his wife migrated west, first to Elk River Station in Sherburne County, Minnesota and then to Stillwater, Washington County, before settling in the city of Minneapolis; through it all, he worked as a miller; Reuben and his family then relocated farther west, arriving in King County, Washington after the Great Seattle Fire of 1889; initially employed in the restaurant industry, Reuben later found work as a railroad conductor before prospecting for gold with son Edward in the western United States and British Columbia, Canada during the 1890s Gold Rush; employed as a U.S. Post Office clerk in charge of the money order and registry departments in Seattle from 1898 to 1902, Reuben died in Seattle at the age of sixty-eight on September 25, 1903 and was interred at that city’s Lakeview Cemetery; meanwhile, his brother John, who had resumed work as a fireman with the Pennsylvania Railroad after returning from the war, was widowed by his wife in 1872; after remarrying and welcoming the births of more children, he was severely injured on October 9, 1873 while working as a fireman on the Pacific Express for the Pennsylvania Railroad; unable to continue working as a fireman due to his amputated hand, he worked briefly as a railroad call messenger before launching his own transfer business in Harrisburg; after he was widowed by his ailing second wife, John was severely injured in a second accident in 1894 while loading his delivery wagon; still operating his business after the turn of the century, he remarried on January 3, 1900, but was widowed by his third wife when she died during a surgical procedure in 1911; he subsequently closed his business and relocated to the home of his daughter in the city of Reading, Berks County; four years later, he fell on an icy sidewalk and became bedfast; aged eighty and ailing from arteriosclerosis and lung congestion, he died at her home on February 20, 1918 and was buried at Reading’s Charles Evans Cemetery;

* Gethers, Bristor (Under-Cook, Company F): Born into slavery in South Carolina circa 1829, Bristor Gethers was married “by slave custom at Georgetown, S.C.” on the Pringle plantation in Georgetown sometime around 1847 to “Rachael Richardson” (alternate spelling “Rachel”); a field hand at the dawn of the Civil War, he was freed from chattel enslavement in 1862 by Union Army troops; he then enlisted as an “Under-Cook” with Company F of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in Beaufort, South Carolina on October 5, 1862, and traveled with the regiment until October 4, 1865, when he was honorably discharged in Charleston, South Carolina upon completion of his three-year term of enlistment; at that point, he returned to Beaufort and resumed life with his wife and their son, Peter; a farmer, Bristor was ultimately disabled by ailments that were directly attributable to his Union Army tenure; awarded a U.S. Civil War Soldiers’ Pension, he lived out his days with his wife on Horse Island, South Carolina, and died on Horse Island, South Carolina on June 24 or 25, 1894; he was then laid to rest at a graveyard on Parris Island on June 26 of that same year;

* Gilbert, Edwin (Captain, Company F): A native of Northampton County and a carpenter residing in Catasauqua, Lehigh County at the dawn of the American Civil War, Edwin Gilbert enrolled as a corporal on August 21, 1861; after rising up through his regiment’s officer ranks, he was ultimately commissioned as a captain and placed in charge of his company on New Year’s Day, 1865, and then mustered out with his company in Charleston, South Carolina of Christmas of that same year; resuming his life with his wife and children in Lehigh County after the war, he continued to work as a carpenter; after suffering a stroke in late December 1893, he died on January 2, 1894 and was buried at the Fairview Cemetery in West Catasauqua;

Mrs. Caroline Bost and Martin L. Guth celebrated the anniversary of President Abraham Lincoln’s birthday with fellow Grand Army of the Republic and ladies auxiliary members in February 1933 (public domain).

* Guth, Martin Luther (Corporal, Company K): A native of Lehigh County and son of a farmer, Martin L. Guth was a seventeen-year-old laborer and resident of Guthsville in Whitehall Township at the dawn of the American Civil War; after enrolling for military service on September 26, 1862, he was officially mustered in as a corporal; he continued to serve with his regiment until he was honorably mustered out on October 1, 1865, upon expiration of his term of service; at some point during that service, he broke his leg—an injury that did not heal properly and plagued him for the remainer of his life; after returning home to the Lehigh Valley, he found work again as a laborer; married in 1883, he became the father of four children, one of whom was born in New Mexico and another who was born in California; he had moved his family west in search of work in the mining industry; documented as a “prospector” or “miner” records created in Nevada during that period, he was also documented on voter registration rolls of Butte City in Glenn County, California in August 1892; by 1900, he was living separately from his wife, who was residing in Bandon, Coos County, Oregon with their two children while he was residing at the Veterans’ Home of California in Yount Township, Napa County, California; subsequently admitted to the Mountain Branch of the network of U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Johnson City, Tennessee on February 11, 1912, his disabilities included an old compound fracture of his right leg with chronic ulceration, defective vision (right eye), chronic bronchitis, and arteriosclerosis; discharged on December 12, 1920, he was admitted to the U.S. National Soldiers’ Home in Leavenworth, Kansas on July 30, 1912, but discharged on September 29, 1913; by 1920, he was living alone on Fruitvale Avenue in the city of Oakland, California, but was remaining active with his local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic as he rose through the leadership ranks of chapter, state and national G.A.R. organizations; after a long, adventure-filled life, he died on October 11, 1935, at the age of ninety-one, at the veterans’ home in San Francisco and was interred at the San Francisco National Cemetery (also known as the Presidio Cemetery);

* Hackman, Charles Abraham and Martin Henry (First Lieutenant and Sergeant, Company G): Natives of Rittersville, Lehigh County, Charles and Martin Hackman began their work lives as apprentices, with Charles employed by a carpenter and Martin employed by master coachmaker Jacob Graffin; members of the local militia unit known as the Allen Rifles, they were among the earliest responders to President Abraham Lincoln’s call to defend the nation’s capital, following the fall of Fort Sumter in mid-April 1861; both enlisted as privates with Company I of the 1st Pennsylvania Volunteers on April 20 and were honorably mustered out in July after completing their service; Charles then re-upped for a three-year tour of duty, mustering in as a sergeant with Company G of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; he then spent most of his early service in Virginia; meanwhile, his younger brother, Martin H. Hackman, who was employed as a coach trimmer in Lehigh County, re-enlisted for his own second tour of duty, as a private with Charles’ company, on January 8, 1862; working their way up the ranks, Charles was commissioned as a first lieutenant on June 18, 1863, while Martin was promoted to sergeant on April 26, 1864; Charles was then breveted as a captain on November 30, 1864 after having mustered out on November 5; Martin was then honorably discharged on January 8, 1865; initially employed, post-war, with the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad’s train car facility in Reading, Berks County, Charles was promoted to car inspector at the company’s Philadelphia facility in December 1866; he subsequently married, but had no children and was widowed in 1904; remarried, he remained in Philadelphia until the early 1900s, when he relocated to Allentown; Martin, who worked as a bricklayer in Allentown, did have children after marrying, but he, too, was widowed; also remarried, he became a manager at a rolling mill; ailing with pneumonia in early 1917, Charles was eighty-six years old when he died in Allentown on January 17; he was buried at Allentown’s Union-West End Cemetery, while his brother Martin was buried at the Nisky Hill Cemetery in Bethlehem, following his death in Bethlehem from a cerebral hemorrhage on December 14, 1921;

* Junker, George (Captain, Company K): A German immigrant as a young adult, George Junker emigrated sometime around the early 1850s and settled in Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, where he found employment as a marble worker and tombstone carver, and where he also joined the Allen Infantry, one of his adopted hometown’s three militia units; responding to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to defend the nation’s capital during the opening weeks of the American Civil War, George enlisted with his fellow Allen Infantrymen, honorably completed his Three Months’ Service, and promptly began his own recruitment of men for an “all-German company” for the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; commissioned as a captain with the 47th Pennsylvania, he was placed in charge of his men who became known as Company K; mortally wounded by a Confederate rifle shot during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862, he died from his wounds the next day at the Union Army’s division hospital at Hilton Head, South Carolina; his remains were returned to his family in Hazleton, Luzerne County for reburial at the Vine Street Cemetery;

* Kern, Samuel (Private, Company D): A native of Perry County who was employed as a farmer in Bloomfield, Perry County when he enrolled for Civil War military service on August 20, 1861, Samuel Kern was wounded and captured by Confederate troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched to Camp Ford, near Tyler, Texas, the largest Confederate prison camp west of the Mississippi River, he was held there as a prisoner of war (POW) until he died from harsh treatment on June 12, 1864; buried somewhere on the grounds of that prison camp, his grave remains unidentified;

* Kosier, George (Captain, Company D): A native of Perry County and twenty-four-year-old carpenter residing in that county’s community of New Bloomfield at the dawn of the American Civil War, George Kosier became one of the earliest men from his county to respond to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for to defend the nation’s capital, following the fall of Fort-Sumter in mid-April 1861, when he enrolled for military service on April 20 as a corporal with Company D of the 2nd Pennsylvania Volunteers; honorably discharged in July after completing his Three Months’ Service, he re-enlisted as a first sergeant with Company D of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; joining him were his younger brothers, Jesse and William S. Kosier, aged nineteen and twenty-three, who were enrolled as privates with the same company; all three subsequently re-enlisted with their company at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida in 1863; sadly, Jesse fell ill with pleurisy and died at the Union Army’s Field Hospital in Sandy Hook, Maryland on August 1864; initially buried at a cemetery in Weverton, Maryland, his remains were later exhumed and reinterred at the Antietam National Cemetery in Sharpsburg, Maryland; both George and William continued to serve with the regiment, with George continuing his rise up the ranks; commissioned as a captain, he was given command of Company D in early June 1865; both brothers were then honorably discharged with their regiment on Christmas Day, 1865; post-war, both men married and began families; William died in Pennsylvania sometime around 1879, but George went on to live a long full life; after settling in Ogle County, Illinois, where he was employed as a carpenter, he relocated with his family to Wright County, Iowa, where he built bridges; he died in Chicago on December 3, 1920 and was buried at that city’s Rosehill Cemetery;

* Leisenring, Annie (Weiser): The wife of Thomas B. Leisenring (Captain, Company G), Annie Leisenring was employed by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania as a factory inspector after the American Civil War; she became well known through newspaper accounts of her inspection visits and also became widely respected for her efforts to improve child labor laws statewide;

* Lowrey, Thomas (Corporal, Company E): An Irish immigrant as a young adult, Thomas Lowrey emigrated sometime around the late 1840s or early 1850s and settled in Northampton County, Pennsylvania, where he found work as a miner, married and began a family; responding to U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s call for volunteers to defend the nation’s capital during the opening weeks of the American Civil War, Thomas enlisted with Company E of the 47th Pennsylvania on September 16, 1861; after completing his three-year term of enlistment, he was honorably discharged in September 1864 and returned home to Pennsylvania, where he resumed work as a coal miner near Shenandoah, Schuylkill County, and where he resided with his wife and children; after witnessing the dawn of a new century, he died in Shenandoah on January 11, 1906;

This image of Julia (Kuenher) Minnich, circa 1860s, is being presented here through the generosity of Chris Sapp and his family, and is being used with Mr. Sapp’s permission. This image may not be reproduced, repurposed, or shared with other websites without the permission of Chris Sapp.

* Magill, Julia Ann (Kuehner Minnich): Widowed and the mother of a young son at the time that her husband, B Company’s Captain Edwin G. Minnich, was killed in battle during the American Civil War, Julia Ann (Kuehner) Minnich became a Union Army nurse at Harewood Hospital in Washington, D.C. during the war in order to keep a roof over her son’s head; she then spent the remainder of her life battling the U.S. Pension Bureau to receive and keep both the U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension and U.S. Civil War Nurse’s Pension that she was entitled to under federal law; forced to go on working into her later years by poverty, she finally found work as a cook at a hotel in South Bethlehem; she died sometime after 1906;

* Menner, Edward W. (Second Lieutenant, Company E): A first-generation American who was a native of Easton, Northampton County, Edward Menner was a sixteen-year-old carpenter when he enrolled for Civil War military service on August 25, 1861; working his way up from private to second lieutenant before he was honorably discharged with his regiment in Charleston, South Carolina on Christmas Day, 1865, he was wounded in the left shoulder during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1864; after returning home to the Lehigh Valley, he secured employment as a hooker with the Bethlehem Iron Company (later known as Bethlehem Steel) on March 15, 1866; he married, begam a family and continued to work in the iron industry for much of his life; he died in Bethlehem on April 25, 1913 and was buried at that city’s Nisky Hill Cemetery;

* Miller, John Garber (Sergeant, Company D): A native of Ironville, Blair County, John G. Miller was a twenty-one-year-old laborer living in Duncannon, Perry County when he enrolled for Civil War military service on August 20, 1861; captured by Confederate troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864 and marched to Camp Ford, near Tyler, Texas, the largest Confederate prison camp west of the Mississippi River, he was held there as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864; returned to active duty with his regiment after receiving medical treatment, he continued to serve until he was honorably discharged with the regiment in Charleston, South Carolina on December 25, 1865; after returning home, he married, began a family and relocated with his family to Philipsburg, Centre County, Pennsylvania, where he was employed as a teamster; returning to Blair County with his family, he resided with them in Logan Township before relocating with them again to Coalport, Clearfield County; suffering from heart disease, he died in Coalport on February 16, 1921 and was interred at the Coalport Cemetery;

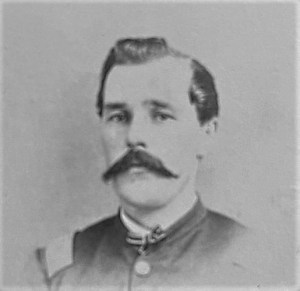

Captain Theodore Mink, Company I, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (circa 1870s-1880s, courtesy of Julian Burley; used with permission).

* Mink, Theodore (Captain, Company I): A native of Allentown, Lehigh County who was apprenticed as a coachmaker and then tried his hand as a whaler and blacksmith prior to the American Civil War, Thedore Mink became one of the “First Defenders” who responded to President Abraham Lincoln’s call for seventy-five thousand volunteers to defend the nation’s capital after the fall of Fort Sumter in mid-April 1861; after honorably completing his Three Months’ Service in July, he re-enlisted on August 5 as a sergeant with Company I of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; after steadily working his way up through the ranks, he was commissioned as a captain and placed in charge of his company on May 22, 1865; he continued to serve with his regiment until it was mustered out on Christmas Day, 1865; following his return to Pennsylvania, he was hired as a laborer with a circus troupe operated by Mike Lipman before finding longtime employment in advertising and then as head of the circus wardrobe for the Forepaugh Circus before he was promoted to management with the circus; felled by pneumonia during late 1889, he died in Philadelphia on January 7, 1890 and was interred in Allentown’s Union-West End Cemetery;

* Newman, Edward (Private, Company H): A German immigrant who left his homeland sometime around 1920, Edward Newman chose to settle in Allentown, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, where he found work as a baker; after enlisting for Civil War military service in August 1862, he mustered in as a private with Company I of the 127th Pennsylvania Volunteers and fought in the Battle of Fredericksburg from December 11-15 of that year; honorably mustered out with his regiment in May 1863, he re-enlisted on October 23, 1863 for a second tour of duty—but as a private with a different regiment—Company H of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers; he continued to serve with the 47th Pennsylvania until he was officially mustered out in Charleston, South Carolina on Christmas Day, 1865, he returned to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, where he worked briefly as a baker; suffering from rheumatism that developed while the 47th Pennsylvania was stationed near Cedar Creek, Virginia during the fall of 1864, he was admitted to the network of U.S. Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers at the Central Branch in Dayton, Montgomery County, Ohio on July 17, 1877; still unmarried and still living there in 1880, his health continued to decline; diagnosed with acute enteritis, he died there on January 22, 1886 and was buried at the Dayton National Cemetery;

* Oyster, Daniel (Captain, Company C): A native of Sunbury, Northumberland County who was employed as a machinist, Daniel Oyster became one of the earliest men from his county to respond to President Abraham Lincoln’s call to defend the nation’s capital, following the fall of Fort-Sumter in mid-April 1861, when he enrolled for Civil War military service on April 23 as a corporal with Company F of the 11th Pennsylvania Volunteers; honorably discharged in July after completing his Three Months’ Service, he re-enlisted as a first sergeant with Company C of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers on August 19; his brother, John Oyster, subsequently followed him into the service, enrolling as a private with his company on November 20, 1863; after rising up through the ranks to become captain of his company, Daniel was shot in his left shoulder near Berryville, Virginia on September 5, 1864 and then shot in his right shoulder during the Battle of Cedar Creek on October 19; successfully treated by Union Army surgeons for both wounds, he was awarded a veteran’s furlough in order to continue his recuperation and returned home to Sunbury; he then returned to duty and was honorably discharged with his company on Christmas Day, 1865; post-discharge, he and his brother, John, returned home to Sunbury; Daniel continued to reside with their aging mother and was initially employed as a policeman, but was then forced by a war-related decline in his health to take less-taxing work as a railroad postal agent; his brother John, who was married, lived nearby and worked as a fireman, but died in Sunbury on April 20, 1899; employed as a bookkeeper after the turn of the century, Daniel never married and was ultimately admitted to the Southern Branch of the U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Hampton, Virginia, where he died on August 5, 1922—exactly sixty-one years to the day after the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was founded; he was given a funeral with full military honors before being laid to rest in the officers’ section at the Arlington National Cemetery on August 11;

* Sauerwein, Thomas Franklin (First Sergeant, Company B): The son of a lock tender in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, Thomas Sauerwein was employed as a carpenter at the dawn of the American Civil War; following his enrollment for military service in Allentown, Lehigh County on August 20, 1861, he was officially mustered in as a private with Company B of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; from that point on, he steadily worked his way up the ranks of the regiment, ultimately being promoted to first sergeant on New Year’s Day, 1865; following his honorable discharge with his company on Christmas Day of that same year, he returned home to the Lehigh Valley, where he found work as a carpenter, married and began a family; by 1880, he had moved his family west to Williamsport in Lycoming County, where he had found work as a machinist; employed as a leather roller with a tanning factory, he was promoted to a position as a leather finisher after the turn of the century, while his two sons worked as leather rollers in the same industry; he died in Williamsport on July 29, 1912 and was buried at the East Wildwood Cemetery in Loyalsock;

* Slayer, Joseph (Private, Company E; also known as “Dead Eye Dick” and “E. J. McMeeser”): A native of Philadelphia, Joseph Slayer was a nineteen-year-old miner residing in Willliams Township, Northampton County, Pennsylvania at the dawn of the American Civil War; after enrolling for military service in Easton, Northampton County on September 9, 1861, he was officially mustered in as a private with Company E of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers; he continued to serve with his company, re-enlisting as a private with Company E, under the name of Joseph Slayer, at Fort Jefferson in Florida’s Dry Tortugas on January 4, 1864; honorably mustered out with his company in Charleston, South Carolina on Christmas Day, 1865, he relocated to Zanesville, Ohio sometime after the war, where he joined the Grand Army of the Republic’s Hazlett Post No. 81; he may then have relocated briefly to St. Paul, Minnesota sometime around the 1870s or early 1880s, or may simply have had a child and grandchild living there, because newspaper reports of his death noted that he had been carrying a photograph of a toddler named Robert—a photo that had “To Grandpa” inscribed on it and indicated that the grandchild, Robert, was a resident of St. Paul in 1892; by the 1880s, Joseph had made it as far west as the Dakota Territory—but this was where his life’s journey took a strange twist; discarding the name he had used in the army (“Joseph Slayer”), he changed his name several times over the next several years, as if he were trying to shed his prior life and all of its associations; acquaintances he met in the southern part of the Dakota Territory during the early to mid-1880s knew him as “Dead Eye Dick” while others who met him after he had resettled in Bismarck, in the northern part of the Dakota Territory, knew him as “Eugene McMeeser” or “E. J. McMeeser” (alternate spelling: “McNeeser”); by the time that the federal government conducted its special census of Civil War veterans in June 1890, Joseph was so comfortable fusing parts of his old and new lives together that he was convincingly documented by an enumerator as “Eugene McMeeser,” a veteran who had served as a private with Company E of the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry from September 9, 1861 until January 11, 1866; in 1890, Joseph became a married man; documented as having rheumatism so severe that he was “at times confined at home,” he filed for a U.S. Civil War Pension from North Dakota on March 28, 1891—but he did so as “Joseph Slayer”—the name under which he had first enrolled for military service in Pennsylvania in 1861; ultimately awarded a pension—which would not have happened if federal officials had not been able to verify his identity and match it to his existing military service records, he was diagnosed with angina pectoris in 1904, but still managed to secure a U.S. patent for one of his inventions—a napkin holder; he died in Bismarck less than a month later, on January 12 or 13, 1905; found on the floor of his rented room, his death sparked a coroner’s inquest which revealed that he had been living under an assumed name; he was buried at Saint Mary’s Cemetery in Bismarck; the name “Joseph Slayer” was carved onto his military headstone;

* Snyder, Timothy (Corporal, Company C): A carpenter who was born in Rebuck, Northumberland County, Tim Snyder was employed as a carpenter and residing in the city of Sunbury in that county by the dawn of the American Civil War; after enlisting for military service as a private in August 1861, he was wounded twice in combat, once during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina (1862) and a second time, in the knee, during the Battle of Opequan, Virginia (1864), shortly after he had been promoted to the rank of corporal; he survived and returned to Pennsylvania, where he resumed work as a carpenter; after relocating to Schuylkill County, he settled in the community of Ashland; in 1870, he married Catharine Boyer and started a family with her; he continued to work as a carpenter in Schuylkill County until his untimely death in May 1889 and was laid to rest with military honors at the Brock Cemetery in Ashland; John Hartranft Snyder, his first son to survive infancy, grew up to become a co-founder of the Lavelle Telegraph and Telephone Company, while his second son to survive infancy, Timothy Grant Snyder, became a corporal in the United States Marine Corps during the Spanish-American War; stationed on the USS Buffalo as it visited Port Said, Egypt, he also served aboard Admiral George Dewey’s flagship, the USS Olympia, in 1899;

Drummer Boy William Williamson, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Company A, circa 1863 (public domain).

* Williamson, William (Drummer, Company A): A farmer from Stockertown, Northampton County, William Williamson was documented by a mid-nineteenth-century federal census enumerator as an unmarried laborer who lived at the Easton home of Northampton County physician John Sandt, M.D.—an indication that William’s parents may have either died or were struggling so much financially during the 1850s and early 1860s that they had encouraged him to “leave the nest” and begin supporting himself, or had hired him out as an apprentice or indentured servant; like so many other young men from Northampton County, when President Abraham Lincoln issued his call for help to protect the nation’s capital from a likely invasion by Confederate States Army troops, he stepped forward, raised his hand, and stated the following:

I, William Williamson appointed a private in the Army of the United States, do solemnly swear, or affirm, that I will bear true allegiance to the United States of America, and that I will serve them honestly and faithfully against all their enemies or opposers whatsoever, and observe and obey the orders of the President of the United States, and the orders of the officers appointed over me, according to the rules and articles for the government of the Armies of the United States.

Later in life, William Williamson became a champion for an older woman who had been struggling to convince officials of the federal government that she was worthy enough to be awarded a U.S. Civil War Mother’s Pension, after her son had died in service to the nation as a Union Army soldier.

Post-war, William Williamson found work at a slate quarry, married, began a family in Belfast, Northampton County, and lived to witness the dawn of a new century. Following his death at the age of sixty in Plainfield Township on June 17, 1901, he was laid to rest at the Belfast Union Cemetery.

Sources:

- “A Badge from Admiral Dewey and Schuylkill County” (announcements of Timothy Grant Snyder’s service on Admiral Dewey’s flagship). Reading, Pennsylvania: Reading Eagle: October 3, 1899 and November 21, 1899.

- Baptismal, census, marriage, military, death, and burial records of the Snyder family. Pennsylvania, California, Florida, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Nevada, Ohio, etc.: Snyder Family Archives, 1650-present; and in Historic Pennsylvania Church and Town Records (baptismal, marriage, death and burial records of various churches across Pennsylvania). Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, 1776-1918.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- James Crownover, James Downs and Samuel Kern, et. al., in Camp Ford Prison Records. Tyler, Texas: The Smith County Historical Society, 1864.

- Civil War Muster Rolls, 1861-1866 (47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, U.S. Army; Admissions Ledgers, U.S. National Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers; federal burial ledgers, and national cemetery interment control forms, 1861-1935. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Office of the Adjutant General (Record Group 94), U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- U.S. Census Records, 1830-1930. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- U.S. Civil War Pension Records, 1862-1935. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.