Dock, Hilton Head, South Carolina, circa 1862 (Sam Cooley, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

They knew they were being ordered to move deeper into enemy territory, but thought their superiors had researched and planned their expedition thoroughly — down to the last bullet they might need if misfortune would befall them.

Confidently boarding their respective transport steamships during the evening of October 21, 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and their fellow Union soldiers from the U.S. Army’s Tenth (X) Corps were ready to head out from the U.S. Department of the South’s main base at Hilton Head, South Carolina on their expedition to Pocotaligo.

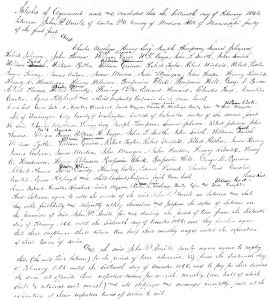

According to reports penned later that month by senior Union Army officers, the troops involved in what was initially labeled the “Expedition to Pocotaligo” (as if it were a planned North Pole exploration, rather than a U.S. Army action against a state that had seceded from the Union), would total roughly 4,500 men who were enrolled in the following units:

- 6th Connecticut Volunteers (500 men);

- 7th Connecticut Volunteers (500 men);

- Hamilton’s Artillery Battery (one full section plus 40 additional men);

- 3rd New Hampshire Volunteers (480 men);

- 4th New Hampshire Volunteers (600 men);

- 1st Massachusetts Cavalry (100 men);

- New York Mechanics and Engineers (250 men);

- 48th New York Volunteers (300 men);

- 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (600 men);

- 55th Pennsylvania Volunteers (400 men);

- 76th Pennsylvania Volunteers 430 men);

- 1st Regiment, U.S. Artillery, Company M (one full section plus 40 additional men); and the

- 3rd Rhode Island Volunteers (300 men);

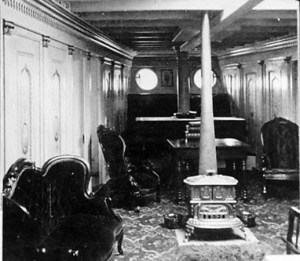

The after cabin inside of the U.S. Steamer Ben Deford, circa 1860s (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

They departed shortly after 12:01 a.m. on October 22, 1862. The Paul Jones, with U.S. Navy Captain Charles Steedman and his small team, steamed away first, followed by the Ben Deford (towing flat-boats with artillery), the Conemaugh and Wissahickon, the Boston (towing flat-boats with artillery), the Patroon and Darlington, the Relief (a steam tug towing a schooner), and the Marblehead, Vixen, Flora, Water Witch, George Washington, and Planter. The flat-boats carried Union Artillery howitzers and/or the light ambulances and wagon that would transport supplies and wounded men. Each of the 4,500 infantrymen involved was equipped with just one hundred rounds of ammunition, which, in hindsight, would prove to be an underestimation of the firepower needed to achieve the mission’s objectives — to destroy the Pocotaligo bridge and as much of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad as possible in the time allotted for the mission.

In addition to Union troops, each of the largest ships also carried a member of the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps to facilitate communication between the vessels, and was staffed by ship pilots from the area — Black men who were experienced navigators who knew exactly where the water hazards were along the Broad River and its tributaries — the Coosawhatchie, Tulifinny, and Pocotaligo rivers, the latter of which was more creek than river.

The first warning of potential trouble ahead came from Mother Nature. “The night proved to be smoky and hazy, which produced some confusion in the sailing of the vessels, as signal lights could not be seen by those most remote from the leading ship.”

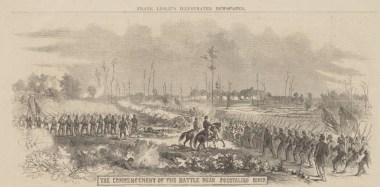

Landing of the U.S. Tenth Army Corps at Mackay’s Point, South Carolina at the start of the Expedition to Pocotaligo, October 22, 1862 (“The commencement of the Battle near Pocotaligo,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 1862, public domain; click to enlarge).

But the Union transports steamed on anyway, slowly progressing toward the mouth of the Pocotaligo River — a distance of roughly twenty-four miles. If all went according to Mitchel’s plan, they would drop anchor at Mackay’s Point, their soldiers protected in their debarkation by their fleet’s gunboats:

There [was] a good country road leading from the Point to the old town of Pocotaligo, then entering a turnpike, which leads from the town of Coosawhatchie to the principal ferry on the Salkehatchie River. The distance to the railroad was only about 7 or 8 miles, thus rendering it possible to effect a landing, cut the railroad and telegraph wires, and return to the boats in the same day…. Presuming that the enemy would make his principal defense at or near Pocotaligo, I directed that a detachment of the Forty-eighth New York, under command of Colonel Barton, with the armed transport Planter, accompanied by one or two light-draught gunboats, should ascend the Coosawhatchie River, for the purpose of making a diversion, and in case no considerable force of the enemy was met, to destroy the railroad at and near the town of Coosawhatchie.

The “landing was effected rapidly and in perfect safety,” according to Mitchel, but as the poet Robert Burns sagely warned in 1785, “proving foresight may be vain: The best laid schemes o’ Mice an’ Men Gang aft agley.” (The best laid plans often go astray.)

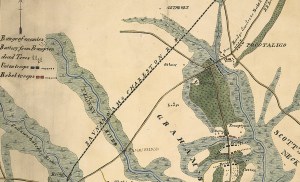

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army’s map of the Pocotaligo-Coosawhatchie Expedition, South Carolina, October 22, 1862. Blue Arrow: Mackay’s Point, where the U.S. Tenth Army debarked and began its march. Blue Box: Position of Union troops (blue) and Confederate troops (red) in relation to the Pocotaligo bridge and town of Pocotaligo, the Charleston & Savannah Railroad, and the Caston and Frampton plantations (blue highlighting added by Laurie Snyder, 2023; public domain; click to enlarge).

Just shy of Mackay’s Point, one of the larger Union ships ran aground, forcing the commanding officers on the scene to slow the expedition’s advance, which caused a delay of between three to four hours, and gave “the enemy full opportunity to make every disposition of his available troops for defensive purposes, and also to telegraph to Charleston and Savannah for reinforcements,” according to Mitchel.

When the transports finally did reach Mackay’s Point, the infantrymen and artillery soldiers quickly pulled together their gear, debarked, formed up for their march, and stepped off toward their intended targets. But, here again, General Mitchel’s planning was off. Completing just three miles of the anticipated “seven or eight” that the primary group was expected to cover to reach its intended target, the Tenth Army infantrymen suddenly ran smack into strongly entrenched Confederate troops.

They fought valiantly, driving the Confederates up and across the Pocotaligo River, and then destroyed the bridge the Confederates had battled so hard to protect. But they were forced to waste precious ammunition and physical energy to do so.

At that point, according to Mitchel, the Tenth Army continued on, re-engaging with the enemy at various points during their advance along narrow, swamp-flanked paths:

The march and fight continued from about 1 o’clock until between 5 and 6 o’clock in the afternoon. The officers and troops behaved in the most gallant manner. One bayonet charge was made over causeways with the most determined courage and with veteran firmness. The advance was made with caution, but with persistent steadiness, driving the enemy over a distance of more than 3 miles, and finally compelling him to seek safety by crossing the Pocotaligo River and the destruction of the bridge. The fight was continued on the banks of the Pocotaligo, but the coming on of night and the exhaustion of our ammunition, as well as the impossibility of crossing the river, rendered it necessary for the troops to return to their boats. This was done in perfect order and with great deliberation. It was impossible for the enemy to harass our troops, as they were on the opposite side of the river and the bridge was destroyed.

So far as I know all the dead and wounded were brought off.

Nothing whatever fell into the hands of the enemy, while they were compelled to abandon two of their caissons, with ammunition, which was returned to them (the ammunition) on the banks of the Pocotaligo from our naval howitzers….

Revising his estimates later in this same report to his superiors, Mitchel wrote:

I regret to say that the main body, under the command of Brigadier-General Brannan, suffered severely in killed and wounded in the three fights, which constituted almost one continuous battle during the afternoon.

I inclose [sic] a list of casualties, which I think is nearly complete, and from which it appears that our loss amounts to about 50 killed and 300 wounded. The loss of the enemy it was of course impossible for us to ascertain.

A few prisoners have fallen into our hands, and we have every reason to believe that the enemy suffered severely.

The greatest activity prevailed on the railroad, and trains of cars with troops appear to have been sent from both Charleston and Savannah.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were among those Union Army troops that Mitchel was referring to in the first and second paragraphs of that quote above.

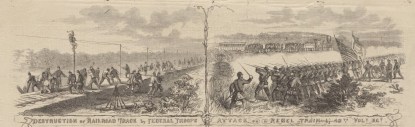

* Note: While all of that was unfolding, the second part of the expeditionary force was carrying out Mitchel’s orders to target a western segment of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad. According to Mitchel, a detachment of Forty-eighth New York Volunteers steamed toward the village of Coosawhatchie aboard the Planter stopping a mile and a half outside of town.

A landing was effected, and the troops of Colonel Barton, accompanied by a detachment of Engineers and Mechanics, marched upon the village. When within about 100 yards of the railroad a train of eight or ten cars came up at high speed, and was received by a volley from our infantry and a discharge from one of the naval howitzers. As the troops were mostly upon platform cars, and very much crowded, this fire must have been very destructive. The engineer was killed, but the train was stopped in the village, and these troops were added to those already guarding the bridge, and this force made it necessary to draw off the Engineers, who were engaged in tearing up the track, having taken with them the tools required for this purpose, and the entire detachment fell back, under the protection of the armed transport and gunboat. The enemy pursued, supposing the Planter to be an unarmed transport, but her heavy guns soon drove them back in disorder, and Colonel Barton, having determined, in his dash upon the village, the position of the village and the depot, shelled them both with his 30-pounder Parrotts for nearly two hours during the afternoon. Before dark he returned to Mackay’s Point, with no loss except the wounding of Lieutenant Blanding, of the Third Rhode Island, whose arm was shattered and his side pierced by a Minie ball.

“Destruction of Railroad Track by Federal Troops” and “Attack on a Rebel Train by 48th Volr. RG.” (“The commencement of the battle near Pocotaligo River,” Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 1862, public domain; click to enlarge). Note: The “48th Volr.” RG.” pictured here was most likely the 48th New York Volunteer Infantry.

How the Battle Actually Unfolded

The initial battle report prepared by Major-General Mitchel proved to be short on details and rosier than the reality.

According to Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, the commanding officer of the expedition who was actually on site (as opposed to Mitchel who was back at Hilton Head, ailing with yellow fever), Brannan “assumed command of the following forces, ordered to destroy the railroad and railroad bridges on the Charleston and Savannah line”:

A portion of the First Brigade (Brannan’s), Col. J. L. Chatfield, Sixth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, commanding, effective strength 2,000; a portion of Second Brigade, Brig. Gen. A. H. Terry commanding, effective strength 1,410; detachment of Third Rhode Island Volunteers, Colonel Brown commanding, effective strength 300; detachment of Forty-eighth Regiment New York State Volunteers, Colonel Barton commanding, effective strength 300; detachment of First Massachusetts Cavalry, Capt. L. Richmond commanding, effective strength 108; section of First U.S. Artillery, Lieut. G. V. Henry commanding, effective strength 40; section of Third U.S. Artillery, Lieut. E. Gittings commanding, effective strength 40; detachment of New York Volunteer Engineers, Lieutenant Colonel Hall commanding, effective strength 250. Total effective strength, 4,448 men.

Departing from Hilton Head with the expeditionary force “on the evening of October 21, and proceeding up Broad River,” Brigadier-General Brannan “arrived off Pocotaligo Creek at 4:30 a.m. with the transport Ben De Ford [sic, Ben Deford] and the gunboat Paul Jones.”

Col. William B. Barton, Forty-eighth Regiment New York State Volunteers, 50 men of the Volunteer Engineer Corps, and 50 men of the Third Rhode Island Volunteers, in accordance with my order, delivered early that morning, proceeded direct to the Coosawhatchie River, to destroy the railroad and railroad bridges in that vicinity. The other gunboats and transports did not all arrive until about 8 a.m. on October 22. I immediately effected a landing of my artillery and infantry at Mackay’s Point, at the junction of Pocotaligo and Tulifiny [sic, Tulifinny] Rivers. I advanced without delay in the direction of Pocotaligo Bridge, sending back the transports Flora and Darlington to Port Royal Island for the cavalry, the First Brigade being in advance, with a section from the First U.S. Artillery, followed by the Second Brigade, with Colonel Brown’s command, the section of the Third U.S. Artillery and three boat howitzers, which Captain Steedman, commanding the naval forces, kindly furnished for this occasion, and a detachment of 45 men from the Third Rhode Island Volunteer Artillery, under Captain Comstock, of that regiment.

“The Commencement of the Battle near Pocotaligo River” (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, October 1862, public domain).

On advancing about 5½ miles and debouching upon an open rolling country the rebels opened upon us with a field battery from a position on the plantation known as Caston’s. I immediately caused the First Brigade to deploy, and, bringing my artillery to the front, drove the rebels from this position. They, however, destroyed all small bridges in the vicinity, causing much delay in my advance. These, with the aid of the Engineer Corps, were reconstructed as we advanced, and I followed up the retreat of the rebels with all the haste practicable. I had advanced about 1¼ miles farther, when a battery again opened on us from a position on the plantation called Frampton. The rebels here had every advantage of ground, being ensconced in a wood, with a deep swamp in front, passable only by a narrow causeway, on which the bridge had been destroyed, while, on our side of the swamp and along the entire front and flanks of the enemy (extending to the swamps), was an impervious thicket, intersected by a deep water ditch, and passable only by a narrow road. Into this road the rebels threw a most terrific fire of grape shot, shell, canister, and musket balls, killing and wounding great numbers of my command. Here the ammunition for the field pieces fell short, and, though the infantry acted with great courage and determination, they were twice driven out of the woods with great slaughter by the overwhelming fire of the enemy, whose missiles tore through the woods like hail. I had warmly responded to this fire with the sections of First and Third U.S. Artillery and the boat howitzers until, finding my ammunition about to fail, and seeing that any flank movement was impossible, I pressed the First Brigade forward through the thicket to the verge of a swamp, and sent the section of First U.S. Artillery, well supported, to the causeway of the wood on the farther side, leaving the Second Brigade, with Colonel Brown’s command, the section of Third U.S. Artillery, and the boat howitzers as a line of defense in my rear. The effect of this bold movement was immediately evident in the precipitate retreat of the rebels, who disappeared in the woods with amazing rapidity. The infantry of the First Brigade immediately plunged through the swamp, (parts of which were nearly up to their arm-pits) and started in pursuit. Some delay was caused by the bridge having been destroyed, impeding the passage of the artillery. This difficulty was overcome and with my full force I pressed forward on the retreating rebels. At this point (apprehending, from the facility which the rebels possessed of heading [to] Pocotaligo Creek, that they would attempt to turn my left flank) I sent an infantry regiment, with a boat howitzer, to my left, to strike the Coosawhatchie road.

Excerpt from the U.S. Army map of the Pocotaligo-Coosawhatchie Expedition, October 22, 1862, showing the positions of the Caston and Frampton plantations in relation to the town of Pocotaligo, the Pocotaligo bridge and the Charleston & Savannah Railroad (public domain; click to enlarge).

The position which I had found proved, as I had supposed, to be one of great natural advantage to the rebels, the ground behind higher on that side of the swamp, and having a firm, open field for the working of their artillery, which later they formed in a half circle, throwing a concentrated fire on the entrance to the wood we had first passed.

The rebels left in their retreat a caisson full of ammunition, which later, fortunately, fitting the boat howitzers, enabled us, at a later period of the day, to keep up our fire when all other ammunition had failed.

Still pursuing the flying rebels, I arrived at that point where the Coosawhatchie road (joining that from Mackay’s Landing) runs through a swamp to Pocotaligo Bridge. Here the rebels opened a murderous fire upon us from batteries of siege guns and field pieces on the farther side of the creek. Our skirmishers, however, advanced boldly to the edge of the swamp, and, from what cover they could obtain, did considerable execution among the enemy. The rebels, as I had anticipated, attempted a flank movement on our left, but for some reason abandoned it. The ammunition of the artillery here entirely failed, owing to the caissons not having been brought on, for the want of transportation from Port Royal, and the pieces had to be sent back to Mackay’s Point, a distance of 10 miles, to renew it.

The bridge across the Pocotaligo was destroyed, and the rebels from behind their earthworks continued on the only approach to it, through the swamp. Night was now closing fast, and seeing the utter hopelessness of attempting anything further against the force which the enemy had concentrated at this point from Savannah and Charleston, with an army of much inferior force, unprovided with ammunition, and not having even sufficient transportation to remove the wounded, who were lying writhing along our entire route, I deemed it expedient to retire to Mackay’s Point, which I did in successive lines of defenses, burying my dead and carrying our wounded with us on such stretchers as we could manufacture from branches of trees, blankets, &.c., and receiving no molestation from the rebels, embarked and returned to Hilton Head on the 23d instant.

Was the U.S. Tenth Army Corps Ambushed?

Brigadier-General Brannan pulled no punches during his post-combat assessment of the Battle of Pocotaligo (now known as the Second Battle of Pocotaligo or the Battle of Yemassee). In his first report to Major-General Mitchel, he made these stunning observations:

Facts tend to show that the rebels were perfectly acquainted with all our plans, as they had evidently studied our purpose with care, and had two lines of defense, Caston and Frampton, before falling back on Pocotaligo, where, aided by their field works and favored by the nature of the ground and the facility of concentrating troops, they evidently purposed making a determined stand; and indeed the accounts gathered from prisoners leave no doubt but that the rebels had very accurate information of our movements.

I greatly felt the want of the cavalry, which, in consequence of the transports having grounded in the Broad River, did not arrive till nearly 4 p.m., and which in the early part of the day would perhaps have captured some field pieces in the open country we were then in, and would at all events have prevented the destruction of the bridge in the rear of the rebels.

Brannan also made clear that the blame for the troops’ tragic lack of ammunition — the primary cause of the Tenth Army’s high casualty rate — rested on Mitchel’s shoulders, and Mitchel’s shoulders alone:

The fitting out of the expedition, as relates to its organization, supplies, transportation, and ammunition, was done entirely by the major-general commanding the department, who at first purposed to command it. I was not assigned to the command till a few hours previous to the sailing of the expedition from Hilton Head.

Commendations for the Valiant

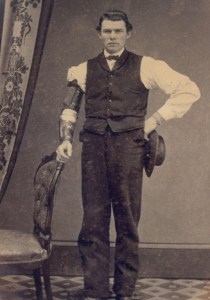

Colonel Tilghman H. Good, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, shown circa 1863, was praised for his performance during the Battle of Pocotaligo in 1862.

Hearteningly, Brigadier-General Brannan devoted a significant portion of his report to Major-General Mitchel by giving credit where credit was actually due — to the officers and enlisted members of the U.S. Army’s Tenth Corps who, despite being hampered by their superiors’ poor, pre-expedition munitions and terrain assessments, still managed to destroy one bridge and inflict significant damage on another segment of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad.

I desire to call the attention of the major-general commanding the department to the gallant and distinguished conduct of First Lieut. Guy V. Henry, First U.S. Artillery, commanding a section of light artillery. His pieces were served admirably throughout the entire engagement. He had two horses shot. The section of Third U.S. Artillery, commanded by First Lieut. E. Gittings, was also well served. He being wounded in the latter part of the day, his section was commanded by Lieutenant Henry.

The three boat howitzers furnished by Captain Steedman, U.S. Navy, commanding the naval forces, were served well, and the officers commanding them, with the crews, as also the detachment of the Third Rhode Island Volunteers, deserve great credit for their coolness, skill, and gallantry. The officers commanding these guns are as follows: Lieut. Lloyd Phoenix and Ensigns James Wallace, La Rue P. Adams, and Frederick Pearson.

1st Lieutenant William W. Geety, Co. H, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, shown here circa 1863, was grievously wounded during the Battle of Pocotaligo (public domain).

The conduct of my entire staff – Capt. Louis J. Lambert, assistant adjutant-general; Capt. L. Coryell, assistant quartermaster, and Lieuts. Ira V. German and George W. Bacon, aides-de-camp – gave me great pleasure and satisfaction. My orders were transmitted by them in the hottest of the battle with great rapidity and correctness. To Col. E. W. Serrell, New York Volunteer Engineers, who acted as an additional aide-de-camp, I am much indebted. His energy, perfect coolness, and bravery were a source of gratification to me. Orders from me were executed by him in a very satisfactory manner. Lieut. G. H. Hill, signal officer, performed his duties with great promptness. He acted also as additional aide-de-camp, and gave me much assistance in carrying my orders during the entire day.

With respect to the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry’s performance, Brannan singled out two of its officers:

Col. T. H. Good, Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers (Colonel Chatfield being wounded early in the day), commanded the First Brigade during the latter part of the engagement with much ability. Nothing could be more satisfactory than the promptness and skill with which the wounded were attended to by Surg. E. W. Bailey [sic, Baily], Forty-seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers, medical director, and the entire medical staff of the command.

Private Jacob Hertzog, Co. K, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, wearing the support device which facilitated his recovery from a gunshot wound during the Battle of Pocotaligo (George A. Otis, public domain).

Regarding the performance of the enlisted and non-commissioned members of the Tenth Army, he noted that:

The troops of the command behaved with great gallantry, advancing against a remarkably heavy fire of musketry, canister, grape, round shot, and shell, driving the enemy before them with much determination. I was perfectly satisfied with their conduct.

It affords me much pleasure again to report the perfect cordiality existing between the two branches of the service, and I was much indebted to Capt. Charles Steedman, U.S. Navy, for his valuable aid and assistance in disembarking and re-embarking the troops; also in sending launches, with howitzers, to prevent an attack on our pickets while we were embarking to return to Hilton Head.

First Lieutenant and Regimental Adjutant Washington H. R. Hangen, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, shown here circa 1864, was seriously wounded in the leg during the Battle of Pocotaligo (public domain).

In his follow-up report to Mitchel, which was penned at Hilton Head, South Carolina on November 6, 1862, Brannan presented a detailed list of the commendations he recommended be issued to the most heroic members of the Tenth Army, many of whom had been killed or grievously wounded at Pocotaligo:

I herewith transmit the reports of Brig. Gen. A. H. Terry and Col. T. H. Good, Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, who commanded brigades during the late expedition, under my command, to Pocotaligo, S.C., and would beg respectfully to bring them to the favorable notice of the department for their gallant and meritorious conduct during the engagement of October 22; as also Col. J. L. Chatfield, Sixth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, who commanded the First Brigade until severely wounded, in the early part of the engagement, while gallantly leading it to the charge. Great praise is also due to General Terry for his care and unremitting exertions during the night of the 22d in superintending the removal of the wounded to the transports.

I also forward the report of Col. E. W. Serrell, First New York Volunteer Engineers, chief engineer of the department, of the part taken by their several commands.

Accompanying General Terry’s report is the report of the success of Lieut. S. M. Smith, Third Regiment Rhode Island Volunteer Artillery,* who was sent up before daylight on the 22d to Cathbert’s Island, on the Pocotaligo Creek, to capture the rebel pickets there stationed.

* Note: General Terry’s reports stated Third New Hampshire Volunteers.

2nd Lieutenant Christian K. Breneman, shown here circa 1863, assumed command of Co. H, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the Battle of Pocotaligo when 1st Lieutenant William Geety was grievously wounded (public domain).

In addition to those officers mentioned in my report of the expedition I have great pleasure, on the recommendation of their respective commanders, in bringing to the favorable consideration of the department the following officers and men, who rendered themselves specially worthy of notice by their bravery and praiseworthy conduct during the entire expedition and the engagements attending it:

First Lieut. E. Gittings, wounded, lieutenant Company E, Third U.S. Artillery, commanding section, who served his pieces with great coolness and judgment under the heavy fire of a rebel battery; Lieutenant Col. G. W. Alexander, Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; Maj. J. H. Filler, Fifty-fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; Capt. Theodore Bacon, Seventh Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, acting assistant adjutant-general Second Brigade; First Lieut. Adrian Terry, Seventh Connecticut Volunteers, and Second Lieut. Martin S. James, Third Regiment Rhode Island Volunteer Artillery, staff of Brigadier-General Terry;

Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, Co. C, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, shown here circa 1863, went on to become Lieutenant Governor of Pennsylvania after the war (public domain).

Capt. J. P. Shindel Gobin, Company C, Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; Capt. George Junker, killed, Company K, Forty-seventh Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers; Captain Mickley, killed, Company G, Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; First. Lieut. W. H. R. Hangen, adjutant, wounded, Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; First Lieutenant Minnich, Company B, Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; First Lieut. W. W. Geety, severely wounded, commanding Company H, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers; Second Lieutenant Breneman, Company H, Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; Private Michael Larkins [sic, Larkin], wounded, Company C, Forty-seventh Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; Captain Bennett, Company E, Fifty-fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; First Lieut. D. W. Fox, commanding Company A, Fifty-fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; First Lieutenant Metzger, adjutant Fifty-fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; First Sergt. H. W. Fox, Company K, Fifty-fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; Private Peter McGuire, Company A, Fifty-fifth Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers; Lieut. S. S. Stevens, Sixth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers, acting assistant adjutant-general First Brigade; Commissary Sergt William H. Johnson, Sixth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers; Sergeant [Charles H.] Grogan, Private G. Platt, and Private A. B. Beers, Company I, Sixth Regiment Connecticut Volunteers; Private R. Wilson, Company D, Sixth Connecticut Volunteers; First Lieut. Edward S. Perry and Private William Crabbe, Company H, Seventh Regiment Connecticut Volunteers; Artificer Patrick Walsh, Company B, First U.S. Artillery; Sergt. Michael Mannon, Light Company E, Third U.S. Artillery; Sergt. N.M. Edwards, First New York Volunteer Engineers, and Sergts. Henry Mehles, Lionel Auyan, and Fisher, First New York Volunteer Engineers.

I would also mention that I am much indebted to Mr. Cooley, sutler of the Sixth Connecticut Volunteers, for his care and attention to the wounded and his care and his exertions in carrying them on the field and placing them on the transports.

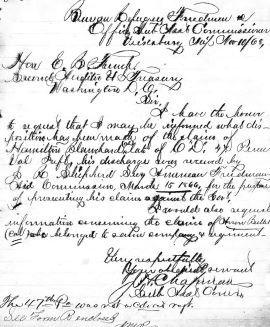

Brannan then closed this second report by attaching “a complete and accurate list of the killed, wounded, and missing during the entire expedition, giving their names, rank, companies, and regiments, with a description of the nature of their wounds.” The New York Times initially estimated that the 47th Pennsylvania, alone, had suffered 140 casualties (killed and wounded), the equivalent of roughly one-and-a-half companies of men, and described the regiment as “terribly shattered.”

Shattered, but valiant. Newspapers across America subsequently carried the following tribute to the 47th Pennsylvania:

They were steady, true and brave. If heavy losses may indicate gallantry, the palm may be given to Col. Good’s noble regiment, the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers. Upon this command the brunt of battle fell. Out of 600 who went into action, nearly 150 were killed or wounded. All of the Keystone troops did splendidly, as did the Connecticut Volunteers, under Chatfield and Hawley.

Next: The Battle of Pocotaligo from the Perspective of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers

Sources:

- “General Orders, Hdqrs., Department of the South, Numbers 40, Hilton Head, Port Royal, S. C., September 17, 1862” (announcement by Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel that he has assumed command of the newly formed Department of the South), in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Prepared Under the Direction of the Secretary of War, By Lieut. Col. Robert N. Scott, Third U.S. Artillery, and Published Pursuant to Act of Congress Approved June 16, 1880, Series I, Vol. XIV, Serial 20, p. 382. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885.

- “Report of Maj. Gen. Ormsby M. Mitchel, U.S. Army, commanding Department of the South and Return of Casualties in the Union forces in the skirmish at Coosawhatchie and engagements at the Caston and Frampton Plantations, near Pocotaligo, S.C., October 22, 1862,” in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Prepared Under the Direction of the Secretary of War, By Lieut. Col. Robert N. Scott, Third U.S. Artillery, and Published Pursuant to Act of Congress Approved June 16, 1880, Series I, Vol. XIV. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885.

- Reports of Brig. Gen. John M. Brannan, U.S. Army, commanding expedition, in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Prepared Under the Direction of the Secretary of War, By Lieut. Col. Robert N. Scott, Third U.S. Artillery, and Published Pursuant to Act of Congress Approved June 16, 1880, Series I, Vol. XIV. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885.

- “The Department of the South: The Recent Attack on the Charleston and Savannah Railroad. Official Report of the Operations at Coosahatchie [sic].” New York, New York: The New York Times, November 11, 1862.

You must be logged in to post a comment.