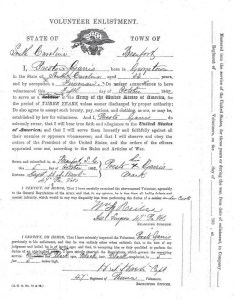

Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, Company C, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, shown here circa 1863, went on to become lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania after the war (public domain).

One of the terms that crops up when researching the history of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers is “court martial”—a phrase that often conjures images of soldiers deserting their posts or behaving in some other dishonorable manner, and who then ended up facing charges of “conduct unbecoming.”

With respect to the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, the phrase “court martial” appears, more often than not, in relation to the service by multiple officers of the regiment who were assigned to serve as judges or members of the jury during trials of civilians in territories where the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were assigned to provost (military police and civilian court) duties, or as judges or members of the jury during the court martials of other members of the Union Army during the American Civil War.

This article presents details about two of the multiple military courts martial in which members of the 47th Pennsylvania were involved.

1862

In mid to late December 1862, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan directed the three most senior officers of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry—Colonel Tilghman H. Good, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander and Major William H. Gausler—to serve on a judicial panel with other Union Army officers during the court martial trial of Colonel Richard White of the 55th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Brannan then also appointed Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin of the 47th Pennsylvania’s C Company as judge advocate for the proceedings.

Of the four, Gobin was, perhaps, the most experienced from a legal standpoint. Prior to the war, he was a practicing attorney in Sunbury, Pennsylvania. Post-war, he went on to serve in the Pennsylvania State Senate and as lieutenant governor of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania.

On December 18, 1862, The New York Herald provided the following report regarding Colonel White’s court martial:

A little feud [had] arisen in Beaufort between General [Rufus] Saxton and the forces of the Tenth Army corps. Last week, during the absence at Fernandina of General Brannan and Colonel Good, the latter of whom is in command of the forces on Port Royal Island, Colonel Richard White of the Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania, was temporarily placed in authority. By his command a stable, used by some of General Saxton’s employes [sic, employees], was torn down. General Saxton remonstrated, and … hard words ensued … the General presumed upon his rank to place Colonel White in arrest, and to assume the control of the military forces. Upon General Brannan’s return, last Monday, General Saxton preferred against Colonel White several charges, among which are ‘conduct prejudicial to good order and military discipline’ and ‘conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.’ General Brannan, while denying the right of General Saxton to exercise any authority over the troops, has, nevertheless, ordered a general court martial to be convened, and the following officers, comprising the detail of the court, are to-day [sic, today] trying the case:— Brigadier General Terry, United States Volunteers; Colonel T. H. Good, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania; Colonel H. R. Guss, Ninety-seventh Pennsylvania; Colonel J. D. Rust, Eighth Maine; Colonel J. R. Hawley, Seventh Connecticut; Colonel Edward Metcalf, Third Rhode Island artillery; Lieutenant Colonel G. W. Alexander, 47th Pennsylvania; Lieutenant Colonel J. F. Twitchell, Eighth Maine; Lieutenant Colonel J. H. Bedell, Third New Hampshire; Major Gausler, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania; Major John Freese, Third Rhode Island artillery; Captain J. P. S. Gobin, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, Judge Advocate. Among the officers of the corps the act of General Saxton is generally deemed a usurpation on his part; and, inasmuch as this opinion is either to be sustained or outweighed by the Court, a good deal of interest is manifested in the trial.

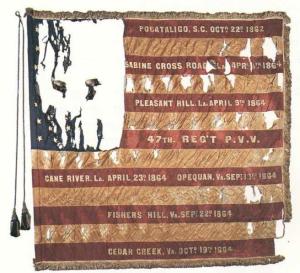

White, whose regiment had just recently fought side-by-side with the 47th Pennsylvania and other Brannan regiments in the Battle of Pocotaligo, was ultimately acquitted, according to subsequent reports by the United States War Department.

1863

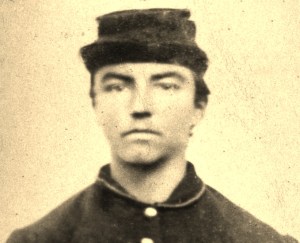

Major William H. Gausler, third-in-command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, 1861-1864 (photo used with permission, courtesy of Julian Burley).

Three months after the aforementioned court martial proceedings, Major William Gausler was called upon again to oversee legal proceedings against his fellow Union Army soldiers—this time serving as president of the courts martial of two members of the 90th New York Volunteer Infantry. Those trials and their resulting findings were subsequently reported by the Adjutant General’s Office of the U.S. War Department roughly a year later as follows:

General Orders, No. 118

War Department, Adjutant General’s Office

Washington, March 24, 1864

I. Before a General Court Martial, which convened at Fort Taylor, Key West, Florida, March 23, 1863, pursuant to Special Orders, No. 130, dated Headquarters, Department of the South, Hilton Head, Port Royal, South Carolina, March 7, 1863, and of which Major W. H. Gausler, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, is President, were arraigned and tried—

1. Captain Edward D. Smythe, 90th New York State Volunteers.

CHARGE I.—“Violation of the 7th Article of War.”

Specification—“In this, that Captain Edward D. Smythe, 90th Regiment New York State Volunteers, did join in a seditious combination of officers of the 90th Regiment New York State Volunteers. This at Key West, Florida, on or about the 20th day of February, 1863.”

CHARGE II.—“Violation of the 8th Article of War.”

Specification 1st—“In this; that Captain Edward D. Smyth, 90th Regiment New York State Volunteers, being present at an unlawful and seditious assemblage of officers of the 90th Regiment New York State Volunteers, held at the Light-house Barracks, Key West, Florida, on or about the 20th day of February, 1863.”

Specification 2d—“In this; that Captain Edward D. Smyth, Company ‘G,’ 90th Regiment New York State Volunteers, having knowledge of an intended unlawful and seditious assemblage of officers of the 90th New York State Volunteers being held at the Light-house Barracks, Key West, Florida, did not without delay give information of the same to his Commanding Officer. This at Key West, Florida, on or about the 20th day of February, 1863.”

CHARGE III.—“Rebellious conduct, tending to excite mutiny.”

Specification 1st —“In this; that Captain Edward D. Smyth, Company ‘G,’ 90th Regiment New York State Volunteers, did, with, thirteen other officers of the 90th New York State Volunteers, tender his resignation, and insist upon its being forwarded, at a time when there were apprehensions of a general resistance to the execution of an order from the Headquarters of the Department of the South. This at Key West, Florida, on or about the 20th day of February, 1863.”

Specification 2d—“In this; that Captain Edward D. Smyth, Company ‘G,’ 90th Regiment New York State Volunteers, did, after so tendering his resignation, positively refuse to withdraw the same when requested to do so by his Commanding Officer, Colonel Joseph S. Morgan, 90th Regiment New York State Volunteers, then commanding the post, he having been notified by Commanding Officer that there were apprehensions of imminent danger at the post. All this at Key West, Florida, on our about the 20th day of February, 1863.”

To which charges and specifications the accused, Captain Edward D. Smyth, 90th New York State Volunteers, pleaded “Not Guilty.”

FINDING.

The Court, having maturely considered the evidence adduced, finds the accused, Captain Edward D. Smyth, 90th New York State Volunteers, as follows:

CHARGE I.

Of the Specification, “Not Guilty.”

Of the Charge, “Not Guilty.”

CHARGE II.

Of the 1st Specification, “Not Guilty.”

Of the 2d Specification, “Not Guilty.”

Of the Charge, “Not Guilty.”

CHARGE III.

Of the 1st Specification, “Guilty, except the words ‘insist upon its being forwarded at a time when there were apprehensions of a general resistance to the execution of an order from the Headquarters of the Department of the South.’”

Of the 2d Specification, “Guilty.”

Of the Charge, “Not Guilty.”

And the Court, being of opinion there was no criminality, does therefore acquit him.

2. 1st Lieutenant Charles N. Smith, 90th New York Volunteers.

CHARGE I.—“Neglect of duty.

Specification—“In this; that the said Lieutenant Charles N. Smith, Company ‘G,’ 90th New York Volunteers, did, on the night of the 10th of March, when he was the Officer of the Day, permit and encourage an enlisted man who was drunk to occupy and sleep in his, the said Lieutenant C. N. Smith’s quarters, and to create an uproar, to the disturbance and annoyance of the officers in the same building, and did not send him, the said enlisted man, although after ‘taps,’ to his proper quarters, or cause him to be quiet.”

CHARGE II.—“Conduct unbecoming an officer and a gentleman, and prejudicial to good order and military discipline.”

Specification—“In this; that the said Lieutenant Charles N. Smith did allow and keep in his quarters all night a drunken enlisted man, and encourage him to speak disrespectfully and abusively of his superior officers; and upon the said enlisted man saying ‘that every officer who had sent in his resignation was a cock-sucking son-of-a-bitch,’ did reply ‘that’s so;’ and did further permit, encourage, and agree to many other things said of a like nature. All this at Key West, Florida, on or about March 10, 1863.”

To which charges and specifications the accused, 1st Lieutenant Charles N. Smith, 90th New York Volunteers, pleaded “Not Guilty.”

FINDING.

The Court, having maturely considered the evidence adduced, finds the accused, 1st Lieutenant Charles N. Smith, 90th New York Volunteers, as follows:

CHARGE I.

Of the Specification, “Guilty, excepting the words ‘encouraged’ or ‘cause him to be quiet.’”

Of the Charge, “Guilty.”

CHARGE II.

Of the Specification, “Guilty of allowing and keeping in his quarters all night a drunken enlisted man.”

Of the Charge, “Guilty, except the words ‘unbecoming an officer and a gentleman.’”

SENTENCE.

And the Court does therefore sentence him, the said Charles N. Smith, 1st Lieutenant, 90th New York Volunteers, “To be reprimanded by his Commanding Officer.”

Trusted to honorably and faithfully fulfill their responsibilities by senior Union Army leaders, those and other officers of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry would be called upon repeatedly for the remainder of the war to serve in similar judicial roles throughout the remaining years of the war.

Sources:

- General Orders No., 118, Washington, March 24, 1864, in Index of General Orders Adjutant General’s Office, 1864. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1865.

- “Our Hilton Head Correspondence.” New York New York: The New York Herald, December 16, 1862.

- “South Carolina.; Military Organization of the Department of South Carolina.” New York, New York: The New York Times, August 8, 1865.

You must be logged in to post a comment.