Charlestown West Virginia, circa 1863 (public domain).

Encamped in early December 1864 with the United States Army of the Shenandoah at its winter quarters at Camp Russell, which was located just west of Stephens City (now Newtown) and south of Winchester, Virginia, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were learning that their stay at this Union Army complex was destined to be shorter than they had hoped. Ordered to prepare for yet another march, they were informed by their superiors that they were being reassigned yet again—this time to help fulfill the directive of Major-General Philip H. Sheridan that the Army of the Shenandoah search out and eliminate the ongoing threat posed by Confederate States Army guerrilla soldiers who had been attacking federal troops, railroad systems and supply lines throughout Virginia and West Virginia.

So, after packing up and saying goodbye to the new friends they’d made at Camp Russell, they began a new, thirty-mile march, five days before Christmas. Trudging north during a driving snowstorm on December 20, 1864, they finally reached Charlestown, West Virginia, where they quickly established their latest “new home” at Camp Fairview, which was situated roughly two miles outside of the village.

Per an 1870 edition of The Lehigh Register, while marching for Charlestown, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers made their way through Winchester and followed the Charlestown and Winchester Railroad line “until two o’clock the following morning” when they were forced to sleep on their arms “until daylight, the guide having lost his way.”

Initially using this camp as the regiment’s winter quarters, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were soon “on constant active duty, guarding the railroad and constructing works for defense against the incursions of guerrillas. The regiment participated in a number of reconnoissances [sic] and skirmishes during the winter”—as the old year of 1864 became the New Year of 1865.

More specifically, by 1865, according to historians at the Pennsylvania State Archives, who had uncovered details about the 47th Pennsylvania’s time at Camp Fairview by reading the diaries of Jeremiah Siders of Company H, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers “were employed building blockhouses at all the railroad ‘posts’ (meaning loading stations).”

A Chaplain Expresses His Thoughts on the Ongoing War

Rev. William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock, chaplain, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, 1863 (courtesy of Robert Champlin, used with permission).

On New Year’s Eve in 1864, the Rev. William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock, the regimental chaplain of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, penned the following words in a report to his superiors:

Camp, 47th Reg. Pa. Vet. Vol’s

Near Charlestown Va, Dec. 31st 1864

Brig. Gen’l L. Thomas,

Adj. Gen’l, U.S. Army

Sir.

I respectfully, beg leave to state that absence from the Reg. accounts for my failing to report for the previous month.

And in submitting my report for the present month it affords me great pleasure to state that the condition and morale of the Reg. is in every respect encouraging.

Of the large number of wounded in the terrible battle of Cedar Creek, Oct. 19th/64, comparatively few have died, probably fourteen, or even a less number will cover the entire loss, whilst nearly all the surviving ones, will be able to join our ranks.

No deaths have occurred in the Reg during the month, whilst few are sick in Hospital, and the health generally is good.

For some time past, the Reg. had been deficient in its quota of officers, but this deficiency is now being happily filled by suitable promotions from the ranks.

In the aggregate it now numbers 882 men. Of which 24 are officers.

In a moral and religious point of view, there is still a large margin for improvement and it is my earnest endeavor to devote all proper and available means for the spiritual welfare of the command.

Under its new organization and in the fourth year of its history, our Reg. has an encouraging future before it.

In conclusion, I may yet say that the review of our National life during the year that is about being numbered with the past, affords rare promise for the future. At no period in the history of our great contest for freedom and Unity has the prospect of returning peace, through honorable conflict, been so promising.

The efforts, the sacrifices, the patience of the loyal states and People are crowned, at last, with triumphs worthy of the holy cause of liberty.

Yet a little while, and we shall rejoice in a peace based on the everlasting foundations of Religion, Humanity, Nationality, and freedom.

For this defeat of traitors at home as well as of Rebels in arms and their sympathizers abroad, for this expression of stern and resolute purpose, for this unshrinking determination to make the last needed sacrifice, how can we be sufficiently grateful?

May the God of our fathers still smile upon us.

I have the honor, Gen’l, to remain,

Very Respectfully, Your Obed’t Serv’nt

W.D. C. Rodrock, Chap., 47th Reg. P.V.V.

2nd Brig. 1st Div. 19th A.C.

* Note: Chaplain Rodrock’s December 31, 1864 report to superiors had noticeable errors, including his significant underestimation of his regiment’s casualty figures during Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign. During the Battle of Cedar Creek alone, more than one hundred and seventy-four members of the 47th Pennsylvania were declared killed, wounded, captured, or missing (forty killed in action, ninety-nine wounded in action, fifteen of whom later died, twenty-five captured, ten of whom later died while still being held as POWs or shortly after their release by CSA troops, nine missing, one unresolved). While he may not yet have had full casualty figures by the time he penned the report above, he would certainly have been able to at least obtain accurate figures regarding the number of men who had been killed and mortally wounded.

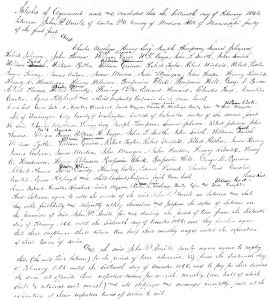

Page one of a report written by the Rev. William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regimental Chaplain, from Camp Fairview, West Virginia to his superiors, January 31, 1865 (U.S. Army, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

Exactly one month later, Rev. Rodrock was putting the final touches on his latest report:

Camp Fairview.

Two miles from Charlestown, Va

January 31st, 1865

Brig. Gen’l L. Thomas

Adj. Gen’l, U.S. Army

Sir.

I have the honor respectfully, to submit the following report for the present month.

Although God is not in men’s thoughts; his law being violated with impunity and his authority contemned “at will”; yet as a nation, our God is the Lord. The mind rest with pleasure on the abounding proof of this great fact. The history of the past, how full of it!

From the first planting of our Fathers on this soil, onward to this day, the true God has been claimed as ours. The foundations of our government were laid in the full and firm apprehension and acknowledgment of this fact. There is one scene recorded in our history which more than all others prove this; we have it commemorated in the engraving of the First Prayer in Congress.

There were the sages and patriots of our land – the representations of the whole country. They had reached a most critical point in their deliberations. They felt the need of higher wisdom than their own. They call in the minister of God, the servant of Jesus Christ; and there and then, in most affecting, service, our country – our whole country is laid at the foot of the Divine throne.

If ever there was heartfelt acknowledgment of a living and true God, and most hearty and sincere invocation of his favor, it was there. For themselves, for their living countrymen, for those to come after them, they cast their all on God, and bound themselves and all to him! Most touching and ever-memorable scene! Worthy the occasion and worthy of a great nation. In this spirit the Christian and the patriot, whether in civic or military life strive to labor, and should fire all hearts and nerve all arms in our present fiery struggle for universal freedom.

I am happy to report the favorable and healthy condition of the Reg. Our aggregate is 891. Of these 19 are transiently on the sick list. No deaths have occurred during the month.

We employ all available means for promoting the temporal and spiritual welfare of the command.

Having a large library of select books, I am prepared to meet the wants of the men in this direction.

Besides I distribute several hundred religious papers among them every week. I am convinced, by experience, that this is one of the effectual and welcome means of gaining the attention of the mass of the men to religious truth, and keeping up the tie between them and the Church at home.

Ever striving to labor with an eye single to the glory of God and our country.

I have the honor,

Gen’l to remain

Your Obed’t Servant

W. D. C. Rodrock

Chaplain, 47th Reg. P.V.V.

2nd Brig. 1st Div. 19th Corps

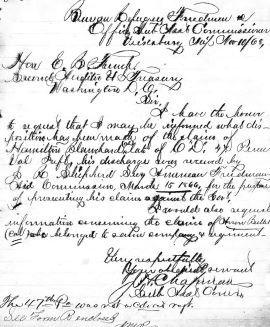

Page one of a report written by the Rev. William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regimental Chaplain, from Camp Fairview, West Virginia to his superiors, February 28, 1865 (U.S. Army, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

While Rev. Rodrock’s next monthly report conveyed the following to his superiors:

Camp Fairview

Near Charlestown, Va

Feb. 28th 1865

Brig. Gen. L. Thomas

Adj. Gen’l U.S. Army

Sir.

I have the honor herewith, to present my report for the month of February.

That blessed peace whose type and emblem is our holy Gospel it is as yet not ours to enjoy. The stern alarums of war still resound in the ears of the nation. And as our victorious columns are marching on, they are sounding the death-knell of the so called Southern Confederacy.

In the strange system and series of paradoxes which make up human life, it often happens that the very disciples of “good will” and brotherly love must buckle on the harness of war. Such emphatically is the case in our present contest. Nor should it be otherwise.

Even our Saviour [sic] came not to bring peace, but a sword until the right should triumph and the sword be beat to a ploughshare. And as our present struggle involves on our side, all that is worthy living for and all that is worth dying for, it may very well fire all hearts and nerve all arms in its behalf.

The Flag which Hernando Cortes carried in that most extraordinary of expeditions in Mexico had for its device, flames of fire on a white and blue ground, with a red cross in the midst of the blaze, and the following words on the borders as a motto, ‘Amici, Crucem sequamur, et in hoc signo vincemur!’ Friends, let us follow the cross, and, trusting in that emblem we shall conquer!’

In these more enlightened times, with more intelligent soldiers, with a purer Church at our back, and with a holier cause, we will keep the motto of Cortes steadily before our eyes; and in personal as in national experience, we shall turn the war into a blessing to the country and to humanity.

It gives me great pleasure to report the improved condition and general good health of the Reg. A large influx of recruits has materially increased our numbers; making our present aggregate 954 men, including 35 commissioned officers.

The number of sick in the Reg. is 22; all of which are transient cases, and no deaths have occurred during the month.

Whilst in a moral and religious point of view there is still a wide margin for amendment and improvement; it is nevertheless gratifying to state that all practicable and available means are employed for the promotion of the spiritual and physical welfare of the command.

And in this connection, I desire to mention our indebtedness to the U.S. Christian Commission for furnishing us with a large supply of excellent reading matter and such delicacies as are highly useful for the Hospital.

That God is in this war of rebellion, that he has brought it upon us, that He over rules it, that its issues are in his hand, that he intends to teach us and the whole world some of the greatest and most sublime lessons ever taught in his providential dealings since the world began, is becoming more and more manifest.

To Him, we will ascribe all Honor and Glory, now and forever.

I have the honor, Gen’l, to remain

Respectfully, Your Obed’t Servant.

W. D. C. Rodrock,

Chaplain, 47th Reg. P.V.V.

2nd Brig. 1st Division, 19th A.C.

Page one of a report written by the Rev. William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry Regimental Chaplain, from Camp Fairview, West Virginia to his superiors, March 31, 1865 (U.S. Army, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

In his final report from Camp Fairview, Rev. Rodrock wrote:

Camp Fairview.

Near Charlestown, Va.

March 31st/65

Brig. Gen’l L. Thomas

Adj. Gen’l U.S. Army

Sir.

I have the honor herewith, to transmit my report for the present month.

Very Respectfully Yours,

W. D. C. Rodrock

Chapl’n, 47th Reg. P. Vols

Camp Fairview

Two Miles from Charlestown, Va.

March 5th/65

Brig. Gen’l L. Thomas

Adj. Gen., U.S. Army

Sir.

I hereby enclose my report for Feb. It having been returned from Brig. Hd. Qrts, to be forwarded direct. In accordance with Gen’l Orders No 158, dated Apl. 13th 1864, I hitherto forwarded my reports through the “usual military channels”. Why I am now ordered to forward direct, is not clear to my mind. Would you have the kindness to forward me any orders issued since the one of the above date & bearing on the duties of Chaplains etc.

If any have been issued, I never recd [sic] them.

I have the honor, Gen’l

To remain, respectfully,

Your Obed’t Servant

W. D. C. Rodrock

Chap. 47th Reg. P.V.V.

2nd Brig. 1st Div. 19th Corps

Washington, D.C.

Camp Fairview, Va.

March 31st 1865

Brig. Gen’l L. Thomas

Adj. Gen’l, U.S. Army

Sir.

Amidst the general glory and success attending our arms on land and sea, it is my pleasant duty to report also the favorable and improved condition of our Reg. for the present month.

In a military sense it has greatly improved in efficiency and strength. By daily drill and a constant accession of recruits, these desirable objects have been attained. The entire strength of the Reg. rank and file is now 1019 men.

Its sanitary condition is all that can be desired. But 26 are on the sick list, and these are only transient cases. We have now our full number of Surgeons, – all efficient and faithful officers.

We have lost none by natural death. Two of our men were wounded by guerillas, while on duty at their Post. From the effects of which one died on the same day of the sad occurrence. He was buried yesterday with appropriate ceremonies. All honor to the heroic dead.

In a moral and religious point of view, we can never attain too great a proficiency. And in our Reg. like in all others, the vices incident to army life prevail to a considerable extent, whatever means may be employed for their restraint.

Still it affords me pleasure to state, that every possible facility is extended the men for moral and religious culture. Divine services are held whenever practicable, and a good supply of moral and religious reading matter, in the form of books and papers, is furnished to the command.

Glory be to the Father and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost; as it was in the beginning, is now, and ever shall be, world without end.

I have the honor, Gen’l

To remain, Respectfully

Your Obed’t. Servant.

W. D. C. Rodrock

Chapl’n, 47th Reg. P.V. Vols

Another New Mission, Another March

“The capitulation and surrender of Robt. E. Lee and his army at Appomattox C.H., Va. to Lt. Gen. U.S. Grant. April 9th 1865” (Kurz & Allison, 16 September 1885, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

According to The Lehigh Register, as the end of March 1865 loomed, “The command was ordered to proceed up the valley to intercept the enemy’s troops, should any succeed in making their escape in that direction.”

By April 4, 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had made their way back to Winchester, Virginia and were headed for Kernstown. Five days later, they received word that General Robert E. Lee had surrendered the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. The long war appeared to be over.

But it wasn’t. In a letter penned to the Sunbury American on April 12, 47th Pennsylvanian Henry Wharton described the celebration that took place following Lee’s surrender while also explaining to residents of his hometown that Union Army operations in Virginia were still continuing in order to ensure that the Confederate surrender would hold:

Letter from the Sunbury Guards.

CAMP NEAR SUMMIT POINT, Va.,

April 12, 1865

Since yesterday a week we have been on the move, going as far as three miles beyond Winchester. There we halted for three days, waiting for the return or news from Torbett’s cavalry who had gone on a reconnoisance [sic] up to the valley. They returned, reporting they were as far up as Mt. Jackson, some sixty miles, and found nary an armed reb. The reason of our move was to be ready in case Lee moved against us, or to march on Lynchburg, if Lee reached that point, so that we could aid in surrounding him and [his] army, and with Sheridan and Mead capture the whole party. Grant’s gallant boys saved us that march and bagged the whole crowd. Last Sunday night our camp was aroused by the loud road of artillery. Hearing so much good news of late, I stuck to my blanket, not caring to get up, for I suspected a salute, which it really was for the ‘unconditional surrender of Lee.’ The boys got wild over the news, shouting till they were hoarse, the loud huzzas [sic] echoing through the Valley, songs of ‘rally round the flag,’ &c., were sung, and above the noise of the ‘cannons opening roar,’ and confusion of camp, could be heard ‘Hail Columbia’ and Yankee Doodle played by our band. Other bands took it up and soon the whole army let loose, making ‘confusion worse confounded.’

The next morning we packed up, struck tents, marched away, and now we are within a short distance of our old quarters. – The war is about played out, and peace is clearly seen through the bright cloud that has taken the place of those that darkened the sky for the last four years. The question now with us is whether the veterans after Old Abe has matters fixed to his satisfaction, will have to stay ‘till the expiration of the three years, or be discharged as per agreement, at the ‘end of the war.’ If we are not discharged when hostilities cease, great injustice will be done.

The members of Co. ‘C,’ wishing to do honor to Lieut. C. S. Beard, and show their appreciation of him as an officer and gentleman, presented him with a splendid sword, sash and belt. Lieut. Beard rose from the ranks, and as one of their number, the boys gave him this token of esteem.

A few nights ago, an aid [sic] on Gen. Torbett’s staff, with two more officers, attempted to pass a safe guard stationed at a house near Winchester. The guard halted the party, they rushed on, paying no attention to the challenge, when the sentinel charged bayonet, running the sharp steel through the abdomen of the aid [sic], wounding him so severely that he died in an hour. The guard did his duty as he was there for the protection of the inmates and their property, with instruction to let no one enter.

The boys are all well, and jubilant over the victories of Grant, and their own little Sheridan, and feel as though they would soon return to meet the loved ones at home, and receive a kind greeting from old friends, and do you believe me to be

Yours Fraternally,

H. D. W.

Two days later, that fragile peace was shattered when a Confederate loyalist fired the bullet that ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln.

Sources:

- “Camp Russell.” The Historical Marker Database, retrieved online December 27, 2023.

- “Civil War, 1861-1865.” Stephens City, Virginia: Newtown History Center, retrieved online December 27, 2023.

- Diaries of Jeremiah Siders (Company H. 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry), in “Pennsylvania Military Museum Collections, 1856-1970” (MG 272). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Dyer, Frederick H. A Compendium of the War of the Rebellion, p. 1589. Des Moines, Iowa: The Dyer Publishing Company, 1908.

- Letters home from ”H.D.W.” and the “Sunbury Guards.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1864-1865.

- Noyalas, Jonathan. “The Fight at Cedar Creek Was Over. So Why Couldn’t Union Troops Let Their Guard Down?” Arlington, Virginia: HistoryNet, 27 February 2023.

- Reports and Other Correspondence of W. D. C. Rodrock, Chaplain, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry (Record Group R29). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 1864-1865.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, July 20, 1870.

You must be logged in to post a comment.