View the video related to this article.

Sibley Tent (Patent #14740, United States Patent Office, April 22, 1856, H. H. Sibley, public domain).

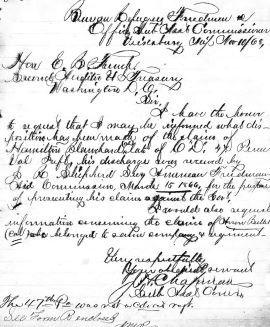

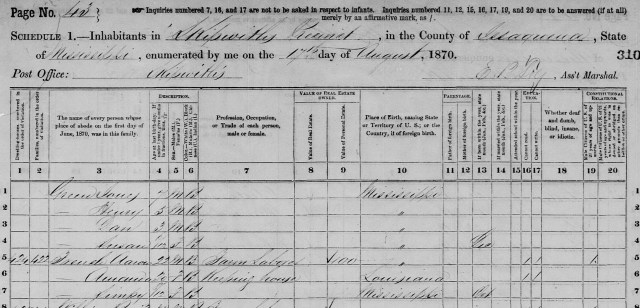

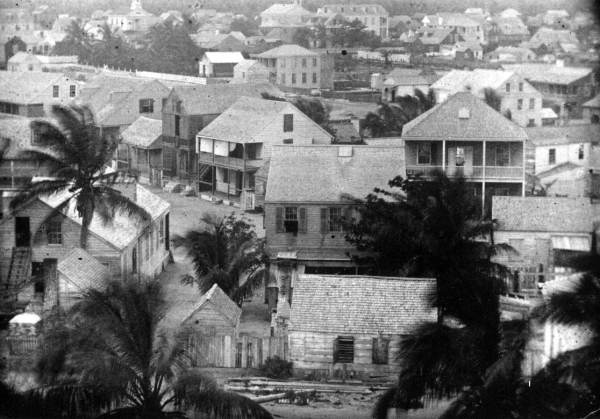

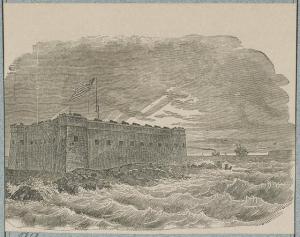

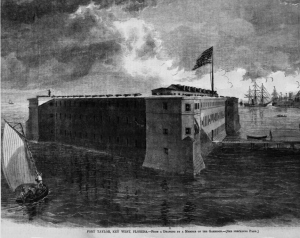

As spring continued to take hold across Pennsylvania in 1862, turning the Great Keystone State’s colorful, budding trees into soothing havens of green-leafed shade, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry continued to battle their great foe—disease. It was a fight that was made more difficult by the regiment’s challenging living conditions. The weather was warm, the water quality was poor, the mosquitos were plentiful, and hygiene was substandard because the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantrymen continued to live in the close quarters of the Sibley tents that had been erected as “Camp Brannan” in Key West, Florida. (The men of Company F were slightly more fortunate, having been previously ordered to live and work at Fort Taylor.)

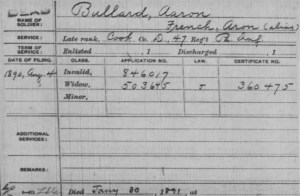

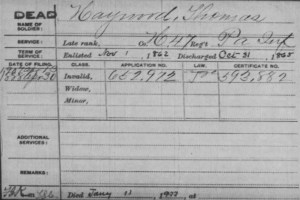

As a result, multiple members of the regiment fell ill during the month of April, including First Lieutenant and Regimental Adjutant Washington H. R. Hangen, who was required to temporarily cede his duties to H Company First Lieutenant William Wallace Geety after being admitted to the officers’ hospital at in Key West, and C Company’s Theodore Kiehl and Henry W. Wolfe, who had been confined to the hospital for enlisted men. Deemed too ill to continue serving with the regiment, F Company privates John G. Seider and Samuel Smith were honorably discharged on surgeons’ certificates of disabilities and sent back home.

Meanwhile, other members of the regiment continued to be advanced in rank, including Second-Sergeant Christian Seiler Beard, who was promoted to First-Sergeant, and Private Peter Haupt who was promoted to the rank of Sergeant—while others assumed additional duties, including D Company privates James E. Albert and William Collins, who were assigned to help the fort’s assistant surgeon, William F. Cornick, in caring for the increased number of patients who had been admitted. Then, General Order No. 84 was issued, directing I Company Captain Coleman A. G. Keck and one of his subordinates, Private William Smith, to return home to Pennsylvania to recruit more volunteers to help beef up the regiment’s dwindling ranks.

In addition, several officers from the 47th Pennsylvania were also called upon to conduct a general court martial trial of a lieutenant from the 90th New York Volunteers who was charged with having been absent from his duties without appropriate authorization (known more commonly today as being absent without leave or “AWOL”). Colonel Tilghman H. Good served as the court’s president, C Company Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin served as its general advocate, and H Company Captain James Kacy was one of the men appointed to serve on the court’s judicial panel, which found the 90th New Yorker guilty and directed that he lose roughly two weeks of pay.

April—May 1862

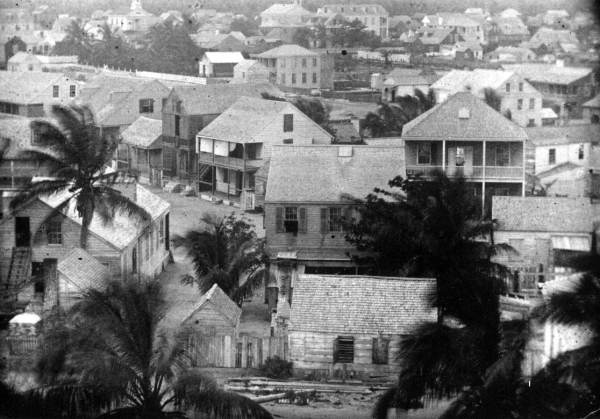

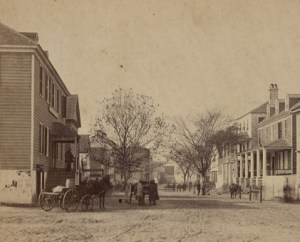

Key West, Florida, circa 1850 (courtesy of Florida Memory Project).

On April 19, the 47th Pennsylvania’s most prolific scribe, C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton, penned a letter to his hometown newspaper, the Sunbury American, from Camp Brannan in Key West:

“DEAR WILVERT:– Having finished a plate of soup, (not a hasty one) enjoyed a piece of ham, cooked in my best style, fried and now luxuriating in a pipe of the best Lynchburg tobacco, I conclude to indite [sic] you a few lines from this most miserable place, Key West.

There are now lying here three very fine vessels captured from Secessia. The cargoes are very valuable, consisting of cotton, coffee, rice, liquor, kerosene and olive oils, leather, and a great many articles of use. I attended the sale of one of the cargoes, and one article I found more numerous than any other—that of hooped skirts. I was curious to know why they had supplied themselves so plentifully with that article, when an old gentleman said that was easily understood, for when the rebels had to run, and in fear of being caught they would make good hiding places, and then he related a circumstance of a Mexican General who, in running away, found crinoline very convenient as a hiding place, but not secure enough for the Lynx-eyed Americans, as the brave gentleman was caught in his wife’s trap.

There has been considerable sickness among the troops, but I am happy to state it is abating. Two members of our company, Theodore Kiehl, and H. Wolf, have been in the Hospital, but are now out and almost ready for duty. They take very readily to their rations when they get back to the company, saying the Hospital is a very nice place to get well in, but no place for grub, as they were as hungry as wolves all the time they were in, or rather when they became better. We have lost eight men from our regiment, by death, since we have been on this island. From what I can learn the diseases were mostly contracted in Virginia, but if they have not, it is a wonder that the mortality is not greater among us, owing to the sudden change of climate, the bad water, hot sun and hard work our men are subjected to.

Lieut. Henry Bush, Co. F., in our regiment, died two weeks ago. His company were in the Fort, learning heavy artillery, where he was attacked with typhoid fever—in a few days he was beyond the physicians [sic] skill, and now he is sleeping his last sleep in the strangers [sic] cemetery. His funeral was very largely attended by the military and the masonic fraternity, of which he was a member. Lieut. Bush was beloved by his company—they having presented him with a sword a few days before he was taken sick—and in fact was liked by the whole regiment for his kindness and gentlemanly bearing to the men. As soon as the necessary arrangements can be made his body will be sent to Catasauqua, Lehigh county, where his widow and two little children reside.

Since the promotion of Lieut. Oyster, there has [sic] been some changes in our company, 2d Sergeant Beard has been made 1st Sergeant, and Peter Haupt, of Sunbury, taken from the ranks and promoted to 1st Sergeant. Haupt passed an excellent examination, and I am proud, for Sunbury, to say that he is considered one of the A. No. 1’s on drill in our regiment.

With the exceptions of a few slight cases of sickness, the boys are getting along very well and would be perfectly contented if they were at a place where there could be a chance to have a hand in some of the glorious victories which their brothers in arms are engaged in, and away from this detested spot, where there would be something to relieve the eye beside sea-gulls, pelicans and turkey-buzzards. Excuse the shortness of this, hoping ere long to be able to give you an account of a victory in which Co. C., was engaged….”

* Note: To read more of Henry Wharton’s insights, please see our collection of his letters here.

By mid-April, typhoid fever was claiming one member of the regiment after another. On Saturday April 19 and Sunday April 27, respectively, K Company privates George Leonhard and Lewis Dipple died at the Key West general hospital while E Company Private John B. Mickley died on April 30.

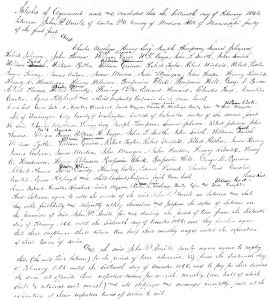

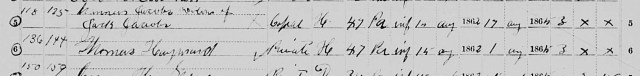

Death ledger entry for Private Lewis Dipple, Company K, “Registers of Deaths of Volunteers,” U.S. Army, 1862 (U.S. National Archives, public domain).

Initially interred in graves numbered nine, ten, and twelve at the fort’s post cemetery, the remains of Privates Leonhard, Dipple, and Mickley were later exhumed for reburial at the Barrancas National Cemetery. Although the process was successfully completed for Privates Leonard and Mickley in 1927, Private Dipple’s remains were handled so disrespectfully that they were later unable to be identified. As a result, they were consigned to a common grave at Barrancas with 227 other “unknown” soldiers.

That same day, General Order No. 26 was announced, directing that:

“I. The troops will be mustered and inspected at 7:45 AM tomorrow morning, 30th inst. April 30, 1862.

II. Immediately after muster, a council of administration to consist of Capt. Harte and officers will assemble to transact such business as regulations require.”

Major-General David Hunter, U.S. Army, circa 1863 (carte de visite, public domain).

Meanwhile, on April 25, 1862, the winds of change had begun to clear the way for long-denied social justice as Union Major-General David Hunter, commanding officer of the U.S. Army’s Department of the South, issued General Orders, No. 11, which directed that all enslaved men, women, and children in Georgia, Florida, and North Carolina be freed immediately:

“Head Quarters Department of the South,

Hilton Head, S.C. May 9, 1862.

General Orders, No 11.— The three States of Georgia, Florida and South Carolina, comprising the military department of the south, having deliberately declared themselves no longer under the protection of the United States of America, and having taken up arms against the said United States, it becomes a military necessity to declare them under martial law. This was accordingly done on the 25th day of April, 1862. Slavery and martial law in a free country are altogether incompatible; the persons in these three States—Georgia, Florida and South Carolina—heretofore held as slaves, are therefore declared forever free.

(Official) David Hunter,

Major General Commanding.”

Although word of Hunter’s order did not immediately reach members of the regiment, it would eventually be carried in newspapers across America.

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers continued to perform their provost and garrison duties in Key West. At the end of April, F Company Private Henry Falk was ordered to take on new duties with the quartermaster while Order No. 21 reassigned H Company Corporal James F. Naylor to the regimental color guard. During the first two days of May, I Company Private William Frack then became Corporal Frack while H Company Private Robert Kingsborough took over quartermaster duties performed previously by Private William O’Brien.

As spring progressed, the weather in Key West became hotter, and the mosquitoes grew even more bold. Even so, the fort’s commanding officer and his subordinates were still able to find a few minutes of relaxation. On May 7, they made time to attend a ball. Corporal James J. Kacey, however, was assigned to fix cartridge boxes around this same time while E Company Corporal George Nicholas was busy dodging disciplinary action, as well as a brush with death:

“I went down to the docks and ask [sic] a Man who owned the Storehouses their [sic] and he said the govemient Seased [sic] them. So I Said I will Sease [sic] the life Boat that laid their [sic]. So I took it up to camp and fixed it up and that got me in trouble I went out Sailing and Missed drill, and got a log to carry, and the next time in the Guard House…. [A] Scorpen Stung me in the finger and I cut a piece out and Sucked it and put Tobacco on it. My arm and hand commenced to Swell Some But Not Much.”

Increasingly debilitated by the bug that had recently felled him, the regiment’s founder and commanding officer, Colonel Tilghman Good, finally realized that he would need to distance himself from his men if he were to continue as their leader. In a letter penned to the Assistant Adjutant, Captain Lambert, he asked “permission to leave camp for a few days, to secure comfortable quarters in town, which I have every reason to believe would materially aid in my speedy restoration to health and strength. The Doctor tells me this desirable end can be attained, by taking rest in elevated and comfortable quarters for a few days. In consequence I do not deem it essential to remove to the hospital.”

Good’s decision proved to be a sound one as more and more members of the regiment were felled by disease, including D Company’s Private George Isett. Suffering from chronic diarrhea, he died on Friday, May 16, and was initially laid to rest in grave no. 14 at the post cemetery. Sadly, his remains were also mishandled when they were exhumed in 1927 for reburial, and were also consigned in the unknown grave of 227 Union soldiers at the Barrancas National Cemetery. His grieving comrades honored him by securing publication of the following Tribute of Respect in their hometown newspaper:

“WHEREAS, it has pleased God in his allwise providence, to remove from our midst our friend and brother in arms, Geo S. Isett; therefore,

RESOLVED, that by his death we have lost a warm hearted friend, a true patriot and good soldier, and one whose place cannot be filled among us.

RESOLVED, That we most heartily sympathize with the deceased and hope that he who has thus afficted [sic] them, will be their reliance in time of need.

RESOLVED, That these resolutions be forwarded to the Perry County papers for publication, and a copy be sent to the friends of the deceased.

Signed: George W. Topley, Jesse Meadith, Jacob Charles, George W. Jury, Isaac Baldwin, Committee.”

That same day (May 16), The Athens Post in Athens, Tennessee specifically mentioned the 47th Pennsylvania’s problems with illness in a news article entitled, “Yankees Sick and Dying”:

“A letter from the flag ship Niagara, published in the Providence Press, fears that the warm weather and imprudence and exposure will cause much sickness among the three Yankee regiments stationed at Key West, Florida. ‘Already the 47 Pennsylvania Regiment has lost a number of its members by the typhoid fever, and I am told they have 70 sick.’ They will have plenty of the same sort before August.”

In response to the continuing wave of sickness, H Company Private Daniel Kochenderfer was reassigned to nursing duties at Key West’s general hospital, where he earned $7.75 for the hazardous duty. Two days later, G Company Private Edmund G. Scholl succumbed to typhoid fever. Initially interred at the post cemetery, Private Scholl’s remains would later be returned home to his family when Allentown undertaker Paul Balliet took on the mission of bringing home both Scholl’s body and that of the infant Regimental Chaplain William Rodrock in 1864. (Both were then reinterred at the “New Allentown Cemetery” on January 30, 1864.)

On May 19, President Abraham Lincoln overturned the emancipation order issued by Major-General David Hunter. His proclamation read as follows:

“Washington [D.C.] this nineteenth day of May,

in the year of our Lord one thousand eight hundred and sixty-two

By the President of the United States of America.

A Proclamation.

Whereas there appears in the public prints, what purports to be a proclamation, of Major General Hunter, in the words and figures following, to wit:

‘Head Quarters Department of the South,

Hilton Head, S.C. May 9, 1862.

General Orders No 11.— The three States of Georgia, Florida and South Carolina, comprising the military department of the south, having deliberately declared themselves no longer under the protection of the United States of America, and having taken up arms against the said United States, it becomes a military necessity to declare them under martial law. This was accordingly done on the 25th day of April, 1862. Slavery and martial law in a free country are altogether incompatible; the persons in these three States—Georgia, Florida and South Carolina—heretofore held as slaves, are therefore declared forever free.

(Official) David Hunter,

Major General Commanding.

Ed. W. Smith, Acting Assistant Adjutant General.’

And whereas the same is producing some excitement, and misunderstanding; therefore I, Abraham Lincoln, President of the United States, proclaim and declare, that the government of the United States, had no knowledge, information, or belief, of an intention on the part of General Hunter to issue such a proclamation; nor has it yet, any authentic information that the document is genuine— And further, that neither General Hunter, nor any other commander, or person, has been authorized by the Government of the United States, to make proclamations declaring the slaves of any State free; and that the supposed proclamation, now in question, whether genuine or false, is altogether void, so far as respects such declaration.

I further make known that whether it be competent for me, as Commander-in-Chief of the Army and Navy, to declare the slaves of any State or States, free, and whether at any time, in any case, it shall have become a necessity indispensable to the maintenance of the government, to exercise such supposed power, are questions which, under my responsibility, I reserve to myself, and which I cannot feel justified in leaving to the decision of commanders in the field. These are totally different questions from those of police regulations in armies and camps.

On the sixth day of March last, by a special message, I recommended to Congress the adoption of a joint resolution to be substantially as follows:

Resolved, That the United States ought to co-operate with any State which may adopt a gradual abolishment of slavery, giving to such State pecuniary aid, to be used by such State in its discretion, to compensate for the inconveniences, public and private, produced by such change of system.

The resolution, in the language above quoted, was adopted by large majorities in both branches of Congress, and now stands an authentic, definite, and solemn proposal of the nation to the States and people most immediately interested in the subject matter. To the people of those States I now earnestly appeal— I do not argue, I beseech you to make the arguments for yourselves— You can not [sic] if you would, be blind to the signs of the times— I beg of you a calm and enlarged consideration of them, ranging, if it may be, far above personal and partizan [sic] politics. This proposal makes common cause for a common object, casting no reproaches upon any— It acts not the pharisee. The change it contemplates would come gently as the dews of heaven, not rending or wrecking anything. Will you not embrace it? So much good has not been done, by one effort, in all past time, as, in the providence of God, it is now your high privilege to do. May the vast future not have to lament that you have neglected it.

In witness whereof, I have hereunto set my hand, and caused the seal of the United States to be affixed.

Abraham Lincoln”

* Note: During the short time in which Major-General David Hunter’s emancipation order was in effect, thousands of enslaved individuals escaped from horrific conditions across Florida, Georgia, and South Carolina, and made their way to the safety of Union military encampments. In response, Hunter directed his subordinates in the U.S. Army’s Department of the South to create a loose network of social services to provide food, clothing, educational services, medical care, and shelter to the newly free men, women, and children. Hunter then also began advocating for able-bodied Freemen to be allowed to enlist with the Union Army.

Although many of these social justice initiatives were put on hold when Lincoln rescinded Hunter’s emancipation order, the disagreement between Lincoln and Hunter evidently made an indelible impression on leaders of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry; just six months later, those 47th Pennsylvanians would pave the way for the regiment to become an integrated one by facilitating the enlistment on October 5, 1862 of several young Black men who were freed from plantations near Beaufort, South Carolina—roughly three months prior to the enactment of Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

As May wore on, disease continued to thin the regiment’s ranks. Another member of the 47th to be felled by typhoid fever was B Company Private John Apple who died at Key West’s general hospital on May 21 (alternate date: March 12). Reportedly buried shortly thereafter and then disinterred from grave number 18 at the fort’s post cemetery in 1927, his remains were also among those that were reportedly consigned to a group grave of 228 unknown soldiers at the Barrancas National Cemetery, according to one source but, according to The Allentown Democrat, were returned to Pennsylvania on January 28, 1864 with the bodies of three other members of the regiment and the body of the regimental chaplain’s infant son. Private Apple was subsequently laid to rest at the Union-West End Cemetery in Allentown on January 31, 1864.

Around this same time, Henry Wharton was dusting off the skills he had learned, pre-war, as an employee of the Sunbury American newspaper. Founding a new publication—the Key West Herald, he was able to get the first edition of his newspaper into the hands of his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians by Saturday, May 24.

The newspaper’s release could not have been more timely. A significant number of his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians were in desperate need of reading material as they fought their way back from sickness. Among those ailing at this time were multiple members of Company D, including privates William Ewing, Samuel Kern, Andrew and William Powell, and Emanuel Snyder, Corporal Samuel Reed, and Sergeants William Fertig and George Topley. Of those, Fertig was the only one to be hospitalized. In addition, B Company Teamster Tilghman Ritz developed rheumatism sometime around the month of May, and underwent several weeks of treatment at the post hospital from the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental surgeon, Elisha Baily. Even though he was treated “successfully” by Baily, however, the condition would continue to plague Ritz for the remainder of his life.

Early June—A Fateful Encounter with Friendly Fire

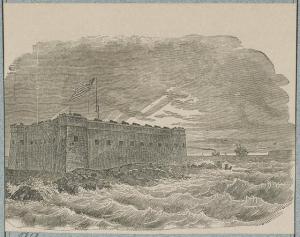

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

One of the most senseless deaths of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the entire war was a “friendly fire” incident which occurred on June 9, 1862. The day had started out peacefully enough—with weather so inviting that I Company Sergeant Charles Nolf, Jr. and several friends felt compelled to take a stroll along the southern portion of the beach in Key West. Tragically, while gathering seashells for family and friends back home, he was accidentally killed by a member of the 90th New York Volunteer Infantry who had been inexplicably playing around with a loaded rifle in violation of brigade regulations while walking on the same stretch of beach with three other members of his regiment—all three of whom had also been carrying loaded rifles—against regulations. Shot in the forehead, Sergeant Nolf died instantly at the scene. Initially interred at the fort’s post cemetery, his body was among the aforementioned group of soldiers’ remains disinterred and returned to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley by Allentown undertaker Paul Balliet, where they were reburied at the Fairview Cemetery in West Catasauqua in late January of 1864.

On the same day that Charles Nolf departed from the world (June 9), First Lieutenant William W. Geety was released from the hospital having successfully recovered from an attack of bilious fever which had resulted in his confinement beginning May 18. In a letter penned to his wife while recuperating, he described himself as “jaundiced.”

Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, U.S. Army (public domain).

By June 11, I Company Captain Coleman Keck was back home in Allentown, Pennsylvania, hard at work recruiting more men to serve with the 47th Pennsylvania. Meanwhile, the “old men” of the regiment—the veterans—were sensing another change in the winds of fate. That change came on Friday, June 13, via General Order No. 53, which was issued by Brigadier-General Brannan:

“The 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Volunteers will hold itself in readiness for immediate embarkation. Company F of this regiment which is detached at Fort Taylor will report at headquarters of the regiment. Each regiment will take six months [sic] supply of medicine and medical stores on embarkation.”

Rumors swirled that the regiment would be shipped to Port Royal, South Carolina in preparation for a Union attempt to wrest control of Savannah, Georgia or Charleston, South Carolina from the control of the Confederacy.

On Saturday, June 14, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers participated in a review with other members of Brigadier-General Brannan’s troops. According to an edition of the New Era, which was published around this same time:

“The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers under command of Lt. Col. Alexander made a fine appearance. Their marching was perfect and the entire regiment showed the effect of careful drill. A more sturdy, soldierly looking body of men cannot be found, probably, in the service. Col. Good and the officers under his command have succeeded in bringing the regiment to a state of military discipline creditable alike to them and the state from which they hail. The regimental band deserves some mention; there are many bands in the service of greater celebrity, whose performances would not bear comparison with that attached to the 47th Regiment.”

On June 16, Wharton penned another letter to his hometown newspaper in which he reflected on the untimely, friendly fire death of Sergeant Nolf and provided further insights into the soldiering life in America’s Deep South:

“Great excitement was caused by the accident, and for a time (our boys not knowing the particulars) some of them were determined to avenge their comrade’s death, but an investigation pronounced it accidental, when they were satisfied. Nolf was a young man of excellent character, beloved by all who knew him, and it seems hard that he should be hurried into eternity in such a manner, and that too, when the carrying of loadened [sic] rifles is strictly prohibited.

There is a family in this city [Key West] by the name of Fift. One of them, A. Fift, after making a fortune out of his Uncle Samuel, (U.S.), thought to make another speck by going to New Orleans to his friend Mr. Mallory, one of Jeff Davis’ Cabinet (?) in the manufacture of gun boats. Mallory and he went into partnership. After finishing boats, while at Memphis, with a considerable amount of Confederate funds in his pocket, (specie) he gave them the slip. Some of his indignant southern friends followed the double traitor, caught him and immediate hung him, thus saving the United States the trouble of buying an extra rope after this war is over. His brother, who has grown fat off the government, and at the time giving aid to secesh, wishing to visit a cooler atmosphere, and act the part of a nabob in the North, was a few days ago provided with a passage to New York in a Government steamer, while on the same vessel, a soldier, for want of room, could not send a box of sea-shells to gratify the curiosity of his friends at home. You can draw your own inference….

The paymaster has come at last and paid us off for four months. The sight of money was new to the boys, and most eagerly accepted by them. The Sunbury boys sent most of their pay home to their friends, very glad to do so, showing that, although far away from home, loved ones are not forgotten.

We have received marching (sailing) orders, and before this reaches you, if winds do not play us false, we will be in South Carolina, and probably before Charleston, helping to reduce the place where this foul rebellion first broke out. I will write to you immediately on our arrival, attempting to give you a description of the voyage, and an account of the manner in which Neptune treated the health and feelings of the boys. All is hurry and bustle in camp, striking tents, &c., so much so that I can scarcely write. We are all well. None of the Sunbury boys left behind….”

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry began a phased departure from Key West.

A Summertime Occupation of South Carolina

Dock, Hilton Head, South Carolina, circa 1862 (Sam Cooley, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

On Tuesday, June 17, 1862, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania assigned to Companies A, F, and D boarded the schooner “Emilene,” and sailed for Hilton Head Island in South Carolina. Also readying for departure this day were the men from Companies B, C, and I, who boarded a brig, the Sea Lark. On June 19, Companies E and H boarded a different ship, which was not identified by regimental clerks in subsequent reports, but was identified in soldiers’ later correspondence as the Tangire. Setting off at 10:02 p.m. in the same direction as their predecessors, they were followed by the men from Companies G and K, who boarded a sloop, the Ellen Benan [identified in later soldiers’ correspondence as the “Ellen Bernard”], and departed at 2 p.m. on June 20—barely dodging the yellow fever epidemic which swept Key West, Florida.

On June 19, just prior to his departure, G Company Sergeant John Gross Helfrich penned a letter to his parents from the Officers’ Hospital in Key West, where he had been assigned as a hospital steward:

“…. We are under marching orders, some of the companies of our regiment have already gone. The reason for our not going together, is owing to not having vessels enough. Those who have left had to embark on small “briggs” & skooners [sic], taking from two to three companies aboard. The place of our destination is ‘Beaufort S. Carolina.’ The two companies of regulars, stationed here, have also left a few days ago; for the same place.

The health of our men is exceedingly good at present, out of our whole regiment there are but nineteen, who are unable on account of sickness to accompany us, which is comparatively, but a very small number, and these as far as my knowledge is concerned, are not dangerously ill; and it is hoped that they may soon be able to follow us.

After we are gone the garrison at this place will only consist of six companies of the 90th Regt. N.Y.V. [90th New York Volunteers]. The other four companies of the above named regt. are stationed at “Fort Jefferson”, Tortugas; some fifty-odd miles from here.

The 91st Regt. N.Y.V. were ordered a few weeks ago, to Pensacola, Fla. So you perceive, that there has been a considerable change made among the military, of late at this place….

Letter from Sergeant John G. Helfrich, Company G, to his parents, June 25, 1862 (used with permission, courtesy of Colin Cofield).

After Helfrich settled into his new quarters at Hilton Head, South Carolina, he penned the following update to his parents on June 25:

“Having first arrived at our place of destination spoken off [sic] in my last, I will now give you a brief description of our passage to this place.

We left Key West, on the 19th inst., about mid-night in the brigg [sic] “Ellen Bernard,” and arrived at this place yesterday (the 24th) at one o’clock p.m. having had a very pleasant voyage, not the slightest accident having occurred, and the men seem to get accustomed to riding at sea, as but a few had what is generally called ‘seasickness’. Our regt. was put on four small vessels, the ‘Sea Lark’, ‘Emaline’, “Tangire’ [handwriting difficult to read] & ‘Ellen Bernard, the second last named, has up to this time, not yet arrived, having started about 4 hours ahead of us. She had three companies aboard & the hospital baggage.

The weather is not quite so hot here as where we come from, but I think it will perhaps make a material change in a few days, as the ground is at present cooled off by the rain….

Since our arrival on this island we learned that a pretty severe fight came off about eighteen miles from here, at a place called ‘James island’ at which our boys seem to have got the worst of it as the hospital at this place contains a great many of the wounded.

Our boys are all eager for a fight, and no doubt they will get a chance to show their fighting abilities ere long, as it is rumored that an assault is to be made on ‘Charleston’ at an early date. Troops are coming and going every day, I am told, and I should not be surprised if we had to go away from here in a day or so.

You must excuse me for writing with red ink as it was the only article of the kind within reach.

I am in the full enjoyment of health at present, hoping you are the same.

I will enclose forty dolls. which I will send to you for safe keeping, until I return home, which will be ere long I reckon. Write soon, as I am anxious to hear from you….”

* Note: The letters of Sergeant John Helfrich are used with permission of Colin Cofield and his family who generously provided copies for use in documenting the history of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. To read more of his insights, see our collection of Helfrich’s letters here.

According to military reports, the first two units of the regiment to arrive at Hilton Head—Companies E and H—disembarked on Sunday, June 22. After having spent four days aboard ship, these men quickly realized their initial accommodations would be far from plush. They were expected to sleep out in the open on the dock. The men from Companies, A, D, and F and B, C, and I arrived next, respectively disembarking from the “Emilene” and “Sea Lark” on Monday. They, too, all spent a restless night sleeping on the dock.

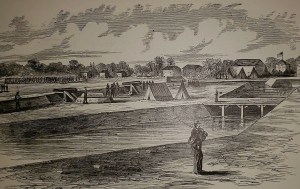

Fort Walker, Hilton Head, South Carolina, circa 1861 (Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, public domain).

Finally, on Wednesday, June 25, at 2 p.m., the regiment was made whole again when the men from Companies G and K arrived on the “Ellen Benan.” The regiment was then marched to the rear of Fort Walker, where the 47th Pennsylvanians were ordered to pitch tents and organize their supplies.

* Note: Per an unspecified military report, Hilton Head was considered to be “a depot to receive army supplies . . . strongly fortified so as to command the channel, and [was] a good depot for troops, as they [could] be sent from there to almost any point needed in [that] part of the south.” Located on opposite sides of the channel from each other, Hilton Head and Port Royal were just fifteen miles upstream from Beaufort, South Carolina, which would ultimately become a long-term duty station for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Fort Walker, which was situated in Hilton Head’s northeast section, “was irregularly shaped in a form that could be roughly described as half an octagon facing the ocean, backed by a slightly larger rectangle, and with a triangle on the inland side,” according to historian Lewis Schmidt. “Located about 1200 feet north of the fort was a pier which extended at right angles from the beach for a distance of 1277 feet. Inland from the fort and pier were numerous auxiliary facilities such as quarters, guard house, stables, quartermaster, ice house, blacksmith, carpenter, post office, bakery, hotel, theatre, church, and numerous other buildings.”

Mitchelville, a village built to house numerous formerly enslaved men, women and children, was located just west of the fort. Facilities of the provost marshal, provost guard, and Union Army’s engineering department, as well as the 60,000-square foot Union Army Hospital at Hilton Head were located on South Carolina’s coastline, just south of the fort.

Bay Street Looking West, Beaufort, South Carolina, 1862 (Sam A. Cooley, 10th Army Corps, photographer, public domain).

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry did not remain in the Hilton Head-Port Royal area long, however; on July 2, the regiment departed for its new assignment—provost (military police and judicial) duties in Beaufort, South Carolina. Still assigned to the command of Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, the 47th Pennsylvanians performed those duties as part of a combined occupying force that included the: 6th Connecticut under Colonel J. L. Chatfield, the 8th Maine under Lieutenant Colonel J. F. Twitchell, three companies of the 4th New Hampshire under Major J. D. Drew, the 7th New Hampshire under Colonel H. S. Putnam, the 55th Pennsylvania under Colonel R. White, the 1st Connecticut Battery under Captain A. P. Rockwell, three batteries of the 1st U. S. Artillery under Captain L. L. Langdon, three companies of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry under Captain A. H. Stevens, Jr., and a detachment of the 1st New York Engineers.

According to Schmidt, roughly two thousand people resided in Beaufort during this time—a “population which sometimes doubled in the summer months with the influx of wealthy planters.”

“The town had been located on Port Royal Island on a slightly higher elevation than the surrounding areas, and on its eastern side was bounded by a channel which is now part of the Intracoastal Waterway connecting Port Royal and St. Helena Sound. There were many large and beautiful homes with large pillars and porches in the southern tradition, and numerous live oak trees scattered throughout the area…. The town was laid out in a rectangle, with streets of fine white sand, but without any sidewalks.”

But it is the first-hand impressions of Beaufort, penned to family and friends by members of the regiment shortly after their arrival, which still provide important insights into life in Union Army-occupied Beaufort during the summer of 1862. Second Lieutenant William Geety noted that every house was “built in from the street with a yard, shade trees and lots of flowers, and that “the Rebels left much behind” while Private Francis Gildner of Company I juxtaposed the hardships and horrors of war with the city’s elegance:

“This is a beautiful place and has good water, and no defects like Key West. The hospital is in a very large building, however when you come inside you come upon a terrible scene. Here are hundreds of army men who have been wounded in the legs, and many were shot in the breast and face. There is an arm or leg amputated daily. The health of the regiment is good, but we hope we do not stay here too long as this area is infested with millions of mosquitoes and sandflies whom plague us both day and night.”

Enslaved men and women on the grounds of Mrs. Barnwell’s home in Beaufort, South Carolina, circa 1860 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Meanwhile, Private John Wantz of D Company dug deeper to produce an even more illuminating analysis:

“The city of Beaufort is, I suppose, one of the handsomest places in the United States. It was inhabited by only the rich, retired planters of the South and they spared no pains nor expense in making it beautiful with art, and nature could not develope [sic] itself more handsomely than it does here. The weather is pleasant the year round. The large shade trees cannot be surpassed for beauty. Their flower gardens are superb and there is not a single house but what is clustered around with orange, lemon, and fig trees; grapes they have in abundance, and in fact everything that the most fastidious could desire to make them happy and contented. They have all the different kind of vegetables that we are blessed with in the North and in much greater abundance. Everything tends to make a person happy and comfortable. Dull care is driven away by the sweet tones of the mocking bird, whose warble is continuously heard, and the air scented with the fragrance of the shrub and honeysuckle.

In time of peace, the question is who lives here? It is answered, ‘none but those who have obtained a fortune’, for a man of limited means could not. The work done here is by slaves, and a man of ordinary means would be obliged to put himself on equality with the negro, and I doubt if there is a man in the North would do so if he was to see the degraded, uneducated and deplorable looking set of negroes there is in this part of the country. They know of nothing but hard work upon the cotton, rice and corn plantations, and do not know why this war is, what was the cause of it, or anything about it, only that their masters were driven away by the soldiers and that some soldiers have driven other soldiers away. I never would have thought there was so much difference between the North and South if I had not seen it.”

By the second week of July, Union Army leaders issued orders directing part of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry to participate in an Expedition to Fenwick Island (July 9), followed by a Demonstration Against Pocotaligo (July 10). In response, the members of H Company marched to Port Royal Ferry, crossed the Coosaw River, and drove off Confederate soldiers who had set fire to the ferry house while out on picket duty. C Company Captain Gobin described the incident later in a letter, noting that “Two companies of our Regiment were thrown across under cover of a gunboat, drove in the rebel pickets, and penetrated into the country for about half a mile” while C Company Musician Wharton wrote:

“That portion of our regiment to whom was assigned picket duty, on the line nearest the enemy, have returned, being relieved by the 7th New Hampshire Volunteers. Our fellows report the duty pleasant, as it was amusing to see the Georgia sharpshooters trying to pop the pickets on post, forgetting that our Springfield rifles were of longer range than theirs, however they soon discovered it, as could be seen, by the way they jumped behind trees whenever our boys returned their fire. Before our party were relieved, two of three companies crossed the river to have some fun, the rebels not liking the appearance of our bright barrels, skedaddled, leaving our men nothing to do but to burn down the houses they had for protection, and the pay for their trouble amounted to a few red cotton overcoats.”

Company Sergeant Reuben S. Gardner added even more details in his own letter to family, writing:

“So the other day we took a notion to turn the joke on them and we crossed over to this side and drove them off their posts and back several miles, and burnt four houses that were used by them to picket in. Our skirmishers had four shots at the rebels, but with what effect we don’t know as they soon got out of harm’s way. Companies H and B were all that crossed. The boys got so eager to follow up the rebels that they did not want to come back when ordered. Our force was too small to advance far, so we went back after doing all the damage we could to them. They fled in such a hurry as to leave three saddles, one double barreled [sic] shot gun, several overcoats, haversacks, canteens, &c., all of which our boys brought along as relics, that being the first of anything of that kind our regiment had. Now the boys want to cross every day; but the Colonel won’t allow them as it is beyond his orders to cross the river, and probably we would meet with a repulse, as the rebels have been in force on the opposite side since we drove them off. They are like a bee’s nest when stirred up. The day after we were over they fired more than a hundred shots at our boys. They returned some shots and only laughed at them. The distance across the river is some 800 to 1000 yards, and of course there can be but little damage done at that distance.”

Meanwhile, back at the regiment’s main camp, Regimental Order No. 160 was announced on July 10:

“I. The old officer of the day will be relieved by the new one at 9 AM at these headquarters.

II. The officer of the day will have charge of the camp and will be held responsible for the proper performance of the duties of the guard, the quietness of the camp and its cleanliness. The old guard under charge of its Captain will report to him immediately after breakfast for police purposes and he will have all rubbish and filth carried from the camp a sufficient distance and then have it buried or burned. He will visit the kitchens and quarters of every company accompanied by its commander immediately after he enters upon his duties and report the condition of the same to these headquarters.

III. The officer of the day will be held responsible for the calls of the hours of service and roll calls. One bugler will be detailed daily to report to him for that purpose.

IV. The attention of company commanders is called to article #28, paragraph #234, revised army regulations which requests all roll calls to be superintended by a commanding officer of the companies and Captains to report the absentees to the Colonel or the commanding officer.

V. Commanders of companies are imperatively directed to have the company quarters, kitches, &c., policed and cleaned immediately after breakfast.

VI. Morning reports of companies signed by the Captains and 1st Sergeants and all applications for special priviledges [sic] of soldiers must be handed to the Adjutant before 8 AM.

Col. Good”

The next day, the men of D Company were ordered to report to picket duty. On Saturday, July 12, Company H was sent out on skirmishing duty, as described by Second Lieutenant Geety:

“Five gunboats came up…Saturday and shelled the shore and crossed over and burned three shanties…. I had command of the right of the skirmish but did not get an opportunity to kill any secessionists. I got a secessionist cap box made in New York and the paper and case of a shell.”

On Sunday, Sergeant Reuben Gardner continued working on his letter to his father:

“We have been on picket now ten days [near the Port Royal Ferry and along the Broad River] and were to be relieved tomorrow; but for some cause are now to stay five days longer. The general rule is ten days; but always whip the horse that pulls the hardest. We are ten miles from camp, and are picketing around the west of the island, for 12 miles along the shore. Five companies of our regiment are out at a time. The rebel pickets are right opposite to us, across the river, and dozens of shots are exchanged every day; but without any effect on our side. The rebel’s [sic] guns fail to reach across. Our rifles will shoot across with a double charge, but we only fire at each other for fun. The 7th New Hampshire were on here before we came out and the rebels made them leave the line. They took advantage of that and crossed over and burnt a ferry house that stood on the end of the causeway on this side….

We have the greatest picket line here entirely. At low tide down along the beach at night you can’t hear thunder, by times, for the snapping of oysters, croaking of frogs, buzzing of mosquitoes, and the noise of a thousand other reptiles and varmints. It beats all I have heard since the commencement of the war. We have had a pretty good time out here on picket and good weather; but 15 days is a little too long to lie in the woods for my fancy….

* Note: Gardner apparently went on in this letter to express a virulent hatred of the formerly enslaved Black men, women, and children who were being employed by the Federal Government to cultivate and harvest the corn and cotton fields located near the regiment’s camp. But it is not clear if the ugliest parts of this letter were actually written by Gardner himself. According to Schmidt, Gardner’s correspondence was “one of the few anti-abolitionist letters uncovered in the correspondence of members of the regiment.” Printed “in a staunchly anti-abolitionist paper, the Perry County Democrat,” the original text of the letter may have been “embellished by the editor” to better align “with the paper’s views.”

Consequently, the managing editor of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story has made the decision not to include that portion of Gardner’s letter here as part of this article. Further research is being conducted in an effort to verify Schmidt’s analysis; if that research is able to be completed, the full text of the letter will be presented with its analysis under the “Letters Home” section of this website.

An Old Foe Resurfaces

Even though the change of scenery for the 47th Pennsylvanians appears to have done some good for morale since they were now being given more opportunities to interact with the enemy, the men were still finding that they were being dogged by their old foe—disease. During the month of July, the following members of the 47th were among those seeking medical treatment:

- Private George Nichols, Company E (admitted July 14, 1862 for treatment of a hernia);

- Private Andrew Burke, Company E (admitted July 17, 1862 for treatment of a boil);

- Private Peter McLaughlin, Company H (admitted July 18, 1862 for treatment of a sprain);

- Private William Ward, Company E (admitted July 18, 1862 for treatment of a carbuncle);

- Private Luther Bernheisel, Company H (admitted July 23, 1862 for treatment of a funiculus condition);

- Private John Bruch, Company E (admitted July 24, 1862);

- Private John Richards, Company E (admitted July 26, 1862 for treatment of a febrile condition);

- Second Lieutenant William Wyker, Company E (admitted July 26, 1862 for treatment of diarrhea);

- Corporal Joseph Schwab, Company F (admitted July 26, 1862 for treatment of bilious remittent fever);

- Sergeant William Hiram Bartholomew, Company F (admitted July 26, 1862); and

- First Lieutenant George W. Fuller, Company F (admitted July 26, 1862 for treatment of piles).

In addition, Earnest Rodman (alternate spelling “Ruttman”) of B Company sustained a severe wound to his lower jaw when his rifle accidentally discharged while he was assigned to picket duty at Beaufort on July 15.

As a result, as hospitalizations and medical discharges from the regiment increased, leaders of the 47th Pennsylvania realized that new enlistees would be needed to stabilize the 47th’s rosters. So, Major William Gausler and Captain Henry S. Harte were sent home to Pennsylvania to announce and manage a recruiting drive. Both arrived in their respective communities of Allentown and Catasauqua on July 15, and remained at home until early November. New recruits were enticed by the following:

- Enlistment Premium: $4

- One Month’s Pay (in advance): $13

- 25% of the Standard Bounty (in advance): $25

- County Bounty: $50

- Additional Bounty (paid at the end of the war or end of the soldier’s term of service): $75

- Regular Monthly Pay: $13

Meanwhile, back in Beaufort, Special Order No. 57 was issued on July 16, directing that:

“The hours of drill specified in the order determining the hours of service must be attended to by all the commanding officers of companies not on special duty. Second, in addition to the established hours of service, commanders of companies will cause the chiefs of squads to drill the squads from 9:30 to 10 AM and from 2:30 to 3 PM under the supervision of a commanding officer. Third, there will be a daily drill for noncommissioned officers from 1 to 2 PM. All noncommissioned officers not on special duty or sick must attend these drills. The Sergeants will be drilled by a 1st Lieutenant who will be detailed for that purpose for one weekend; the Corporals by a 2nd Lieutenant who will be detailed in the same manner. They will assemble in front of the color line, under the shade trees, at the sound of the Sergeants call. Lt. Fuller and Lt. Dennig are hereby detailed for that purpose and they will report to these headquarters immediately after drills to report all absentees. Fourth, a roster of each squad with the name of its chief at the head will be furnished to these headquarters as soon as practicable. Col. Good”

As the month of July wound down and hot days tested the patience of 47th Pennsylvanians, tempers flared. On July 24, Private William Kirkpatrick of D Company lost his cool and told his superior, Sergeant Alex D. Wilson, to “go to hell” after Wilson ordered him to add axe-grinding to his duties. Four days later, Kirkpatrick was brought before a military tribunal for “conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline.” Although he pleaded not guilty, he was convicted by the presiding officer, Captain Charles H. Yard, was sentenced to “close confinement for three days on a bread and water diet,” and was also required to forfeit a third of one month’s pay.

On July 29, Musician Daniel Fritz and Private Rudolph Fisher, both of Company K, were discharged on surgeons’ certificates of disability. Fritz, who had contracted typhoid fever and was also losing his eyesight, survived, but Fisher succumbed to his illness at a Union Army hospital in New York.

For much of July, 47th Pennsylvanians had been been assigned to picket duty at or near Port Royal Ferry; they would continue to perform similar duties in the same area throughout most of August as well. Company E would be assigned to “Barnwells” while men from Company D would be stationed near “Seabrook.”

August

As summer wore on, disease and injury continued to take out more members of the regiment. Among those hospitalized were:

- Private Israel Reinhard, Company G (admitted August 6, 1862 for treatment of bilious remittent fever);

- Corporal Solomon Wieder, Company G (admitted August 6, 1862 for treatment of otitis);

- Sergeant Robert Nelson, Company H (admitted August 7, 1862 for treatment of intermittent fever);

- Private Charles Rohrer, Company H (admitted with August 8, 1862 for treatment of diarrhea); and

- Sergeant James Hahn, Company H (admitted August 10, 1862 for dysentery).

The month of August was particularly hard due to typhoid fever, which felled locals and soldiers alike in and around Hilton Head, Beaufort, and Port Royal. Yellow fever then also descended on Hilton Head. One of the protective measures employed by members of the regiment at this time, according to a letter penned by Private Alfred C. Pretz, was “liquid ammonia … kept in the office for the purpose of washing the skin where the little stingers [mosquitos] have sown their venom.”

Robert Barnwell Rhett’s home (“Secession House”), Beaufort, South Carolina, circa 1860s (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

It was also unbearably hot. In a letter to family and friends, C Company Captain Gobin noted that:

“The thermometer to-day has fallen to a respectable number … The weather for the last few weeks has been beyond conception. It was sweltering until Saturday a cool breeze from the North sprung up, and we have enjoyed two comfortable days … Every day last week until Saturday, it ranged from 100 to 110 degrees in our tents, and from 98 to 105 the coolest place you could find…. Our pickets at Seabrook, a few days ago, discovered the rebels throwing up earthworks, and the general impression is that a simultaneous attack will be made by their land forces. News has been received here for some time, of their concentrating large forces of the latter at Grahamsville and Pocotaligo….

But it was these two sentences of Gobin’s letter which provided the most illuminating details about what life was genuinely like for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who were now truly part of an occupying army in America’s Deep South:

“We occupy the house of Senator Rhett, which is one of the finest in the place. A large portion of the furniture is still in it, as is also a portion of his library. It is a magnificent residence, surrounded by orange trees and flowers of the most gorgeous colors. I presume he never intended it for the occupancy of Yankee Court Martial.”

Robert Barnwell Rhett (1800-1876) was, in fact, a powerful, longtime, pro-slavery, pro-secession activist. A native of Beaufort, South Carolina who began his professional life as a lawyer, he quickly became a vocal critic of the Tariff of 1828 (the “Tariff of Abominations”) while serving as a member of the South Carolina state House of Representatives (after he was first elected in 1826). Resigning that seat to become South Carolina’s Attorney General in 1832, he was subsequently elected to represent South Carolina in the U.S. House of Representatives (1837). A supporter of John C. Calhoun, Rhett ultimately parted ways with him when he came to believe that Calhoun was too moderate.

“The Union Is Dissolved” (South Carolina’s secession from the United States as announced by the Charleston Mercury, December 20, 1860 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

By the mid-1840s, Rhett had worked his way into an even more powerful role, becoming the de facto leader of the “fire eaters”—South Carolina’s increasingly vocal, pro-secession movement. Opting not to seek reelection in 1849, he was elected to the U.S. Senate in December of 1850, but resigned that seat in 1852 when his efforts to advance the cause of secession stalled. He then turned to journalism. Purchasing the Charleston Mercury during the 1850s in partnership with his son, Barnwell, he used that newspaper to fan the embers of secession into a raging wildfire—going so far as to call for South Carolina to secede if U.S. voters selected any Republican candidate as the next President of the United States.

As a result, after Abraham Lincoln was elected to his first term, South Carolina seceded on December 20, 1860—just as Rhett had hoped. Rhett then lobbied multiple southern states to meet in Montgomery, Alabama in order to form a new country—one that he envisioned would be made up entirely of slaveholding states.

During what historians now refer to as the Montgomery Convention, Rhett played a key role in drafting a new constitution for the Confederate States of America (CSA). Among his contributions to that document were a stipulation that all future CSA presidents would serve six-year terms and wording that would prohibit future CSA leaders from levying tariffs; but, he failed in his attempt to remove wording that declared foreign slave trade to be illegal, and also failed at adding a provision that would have required all CSA states to allow the practice of slavery.

The sun was already beginning to set on his political career, however; by the time the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Beaufort, Rhett had lost the support of many fellow Confederates after having repeatedly denounced CSA President Jefferson Davis in the Charleston Mercury. Knowing that his hometown of Beaufort had fallen to the U.S. Army and that his Beaufort home had been commandeered for use by the 47th Pennsylvania for provost actions only served to stoke his anger and frustration.

Orders from on High

Directed by President Abraham Lincoln to participate in a parade to honor the late former President Martin Van Buren, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry turned out in full dress uniform on August 15 to listen to prayers and a eulogy. The regimental colors and officers’ sleeves subsequently remained covered with the appropriate designations of mourning for six months after the event. That same day, the regiment was also ordered to engage in enhanced bayonet drills per General Order No. 26.

Six days later, the 47th Pennsylvania lost its renowned Regimental Band when the ensemble (Pomp’s Cornet Band) was formally mustered out of service by the order of the U.S. Congress and U.S. War Department, which had deemed Union Army bands to be an unnecessary expense as the Civil War continued to rage.

While Gobin and other officers of the 47th Pennsylvania were busy with their judicial activities, regimental physicians and their soldier-patients continued their war against disease. Writing to superiors from the 47th Pennsylvania’s headquarters in Beaufort, South Carolina on August 31, Assistant Regimental Surgeon Jacob H. Scheetz reported that:

“Remittent Fever has prevailed to a considerable extent. It was characterized by a daily exacerbation and remission. The greater number of those afflicted with it, presented the following symptoms: A general feeling of lassitude for two or three days, with partial loss of appetite, followed by chills and flashes of heat alternately; cephalgia, felt principally over the orbits, of a sharp lancinating character, sometimes, however, described as a dull, aching, heavy sensation. The eyes were most generally suffused, skin sallow, tongue coated, thirst, anorexia. The bowels in the greater number of cases were torpid, but in others disposed to looseness; there was a tenderness over the right hypochondriac and epigastric regions, frequent nausea, and sometimes vomiting. The pulse ranged from 85 to 115 per minute. The skin was hot and dry during the exacerbations, moist and flacid [sic] during remissions. The urine was generally high colored, and caused frequent complaints of a scalding sensation while voiding it, and there was a continual complaint of pain in the back and extremities, etc. The treatment which was found most beneficial was to administer a mercurial purgative in cases in which the bowels were torpid; when there was nausea, twenty grains of ipecacuanha were combined with it. After the intestinal canal had been acted upon, five grains of quinine were given four to six times daily. When there was diarrhea, half a grain of opium or five of Dover’s powder were given with each alternate dose. When the peculiar effects of the quinia were apparent the disease rapidly yielded. The epigastric tenderness, when severe, was treated with sinapisms and opiates. The diet was light as possible.”

Scheetz also noted that, “Diarrhea prevailed considerably,” and added that the “cases were uniformly mild … unaccompanied by any febrile symptoms, and yielded to treatment very readily”—a protocol which “consisted of vegetable astringents and opium, tannic acid, and catechu being the astringents principally used.”

“Dysentery also assumed a mild type, very few cases presenting much febrile action. The treatment consisted in administering two grains of tartar emetic with half an ounce of epsom salts, and following it with a combination of acetate of lead and opium or more frequently two drachms of castor oil and forty drops of laudanum three times daily.”

Early to Mid-September

Design of the U.S. Army’s insignia for the Tenth (X) Army Corps, which would have been sewn onto uniforms of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry as a badge and displayed on a flag carried by the regiment.

On September 1, a Monday, Wharton penned another letter to the Sunbury American, confirming that:

“The right wing of our regiment, Company C included, have been on picket for the last ten days, tomorrow they return, being relieved by the 8th Maine Volunteers. Our fellows have had a sorry time of it so far as the elements were concerned for it has done nothing but rain, rain, and to get a sight of the sun, in that time was really reviving … the continual change of apparel, when the wardrobe is not very extensive, made it rather inconvenient for them, and more than one in need for a change of flannel had to make a shift without it….

Picket duty here is different from that in Virginia. There 24 hours did the business for one company for ten days, while here 500 men, besides a battery are the quantity required for that length of time. A river divides our line from the rebels and shots are continually exchanged with them, none, however, doing much damage. Occasionally a secesh horseman has temerity enough to come within shooting distance of our Springfields, when he is accomodated [sic] with their merry barkings, but in an instant he skedaddles, and that in such a hurry that does no credit to Southern chivalry or one who is willing to die in the last ditch.”

As summer wound down, two major changes were made to Union Army operations which would dramatically reshape the lives of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers for the remainder of 1862. The 47th Pennsylvania was attached to the newly formed Tenth Army Corps (X Corps) after it was formed as a new army corps on September 3. On September 16, the Tenth Army was then placed under the command of Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel when he took over command of the U.S. Department of the South from Major-General David Hunter.

As a direct result of those changes, before the month was out, disease would no longer be the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry’s primary foe.

View the video related to this article.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Berlin, Ira, Barbara J. Fields, et. al. Freedom: A Documentary History of Emancipation, 1861-1867, Series I, Vol. I, pp. 123-125: “The Destruction of Slavery.” New York, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Berlin, Ira, Barbara J. Fields, et. al. Free at Last: A Documentary History of Freedom, Slavery, and the Civil War, pp. 46-48. New York, New York: The New Press, 2007.

- Farrell, Michael. “History of the Formation of the Tenth Army Corps,” in “Department General Order No. 2 (Series 2013-2014, August 15, 2013).” Boca Raton, Florida: Sons of Union Veterans of the Civil War (Department of Florida).

- Hunter, Major-General David. “Abstract from Return of the Department of the South, Major General David Hunter, U. S. Army, commanding, for July 31, 1862,” in The War of the Rebellion: Official Records of the Civil War: Chapter XXVI: “Operations on the Coast of South Carolina, Georgia, and Middle and East Florida, Apr. 12, 1862-Jun 11, 1863: Correspondence, etc.: Union.” Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885.

- Lincoln, Abraham. “Proclamation by Abraham Lincoln, May 19, 1862, #90” (rescinding Major-General David Hunter’s Emancipation of Enslaved Persons in Georgia, Florida, and South Carolina via General Order No. 11), in “Presidential Proclamations” (Series 23, Record Group 11). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Miller, Steven. “Proclamation by the President,” in “Freedmen & Southern Society Project.” College Park, Maryland: University of Maryland, College Park (History Department), June 19, 2020.

- Reynolds, Michael S. “Rhett, Robert Barnwell,” in South Carolina Encyclopedia. Columbia, South Carolina: University of South Carolina, Institute for Southern Studies, October 25, 2016.

- “Registers of Deaths of Volunteers” (1862 U.S. Army death ledger entries for multiple members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “Yankees Sick and Dying.” Athens, Tennessee: The Athens Post, May 16, 1862.

You must be logged in to post a comment.