Boat Landing, Beaufort, South Carolina, February 1862 (Timothy O’Sullivan, U.S. Army, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Still stationed far from home during the middle of the second year of the American Civil War, the officers of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry marked the first anniversary of their regiment’s mustering in to the Union Army by issuing a series of orders to protect their subordinates and facilitate the continued smooth operation of their organization.

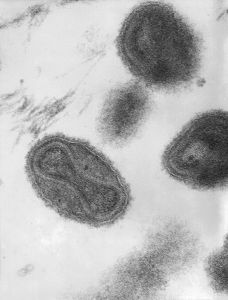

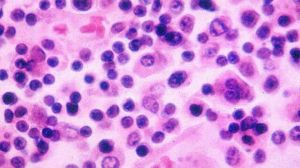

Colonel Tilghman H. Good, concerned about his men’s repeated battles with smallpox, typhoid, and dysentery, announced key procedural changes as follows:

“Beaufort, S.C. Sept 12th, 1862

Regimental Order No. 207

I. The Colonel commanding desires to call the attention of all officers and men in the regiment to the paramount necessity of observing rules for the preservation of health. There is less to be apprehended from battle than disease. The records of all companies in climate like this show many more casualties by the neglect of sanitary post action than by the skill, ordnance and courage of the enemy. Anxious that the men in my command may be preserved in the full enjoyment of health to the service of the Union. And that only those who can leave behind the proud epitaph of having fallen on the field of battle in the defense of their country shall fail to return to their families and relations at the termination of this war.

II. All the tents will be struck at 7:30 a.m. on Monday, Wednesday and Saturday of each week. The signal for this purpose will be given by the drum major by giving three taps on the drum. Every article of clothing and bedding will be taken out and aired; the flooring and bunks will be thoroughly cleaned. By the same signal at 11 a.m. the tents will be re-erected. On the days the tents are not struck the sides will be raised during the day for the purpose of ventilation.

III. The proper cooking of provisions is a matter of great importance more especially in this climate but have not yet received from most of the offices of the regiment that attention that should be paid to it.

IV. Thereafter an officer of each company will be detailed by the commander of each company and have their names reported to these headquarters to superintend the cooking of provisions taking care that all food prepared for the soldiers is sufficiently cooked and that the meats are all boiled or seared (not fried). He will also have charge of the dress table and he is held responsible for the cleanliness of the kitchen cooking utensils and the preparation of the meals at the time appointed.

V. The following rules for the taking of meals and regulations in regard to the conducting of the company will be strictly followed. Every soldier will turn his plate, cup, knife and fork into the Quarter Master Sgt who will designate a permanent place or spot for each member of the company and there leave his plate & cup, knife and fork placed at each meal with the soldier’s rations on it. Nor will any soldier be permitted to go to the company kitchen and take away food therefrom.

VI. Until further orders the following times for taking meals will be followed. Breakfast at six, dinner at twelve, supper at six. The drum major will beat a designated call fifteen minutes before the specified time which will be the signal to prepare the tables, and at the time specified for the taking of meals he will beat the dinner call. The soldier will be permitted to take his spot at the table before the last call.

VII. Commanders of companies will see that this order is entered in their company order book and that it is read forth with each day on the company parade. All commanding officers of companies will regulate daily their time by the time of this headquarters. They will send their 1st Sergeants to this headquarters daily at 8 a.m. for this purpose.

Great punctuality is enjoined in conforming to the stated hours prescribed by the roll calls, parades, drills, and taking of meals; review of army regulations while attending all roll calls to be suspended by a commissioned officer of the companies, and a Captain to report the alternate to the Colonel or the commanding officer.

At 5 a.m., Commanders of companies are imperatively instructed to have the company quarters washed and policed and secured immediately after breakfast.

At 6 a.m., morning reports of companies requested by the Captains and 1st Sergeants and all applications for special privileges of soldiers must be handed to the Adjutant before 8 a.m.

By Command of Col. T. H. Good

W. H. R. Hangen, Adj.’”

Good’s order also delineated the regiment’s daily schedule:

- Reveille (5:30 a.m.) and Breakfast (6:00 a.m.)

- First Call for Guard (6:10 a.m.) and Second Call for Guard (6:15 a.m.)

- Surgeon’s call (6:30 a.m.)

- First Call for Company Drill (6:45 a.m.) and Second Call for Company Drill (7:00 a.m.)

- Recall from Company Drill (8:00 a.m.)

- First Call for Squad Drill (9:00 a.m.) and Second Call for Squad Drill (9:15 a.m.)

- Recall from Squad Drill (10:30 a.m.)

- Dinner (12:00 p.m.)

- Call for Non-commissioned Officers (1:30 p.m.) and Recall 2:30 p.m.

- First Call for Squad Drill (3:15 p.m.) and Second Call for Squad Drill (3:30 p.m.)

- Recall from Squad Drill (4:30 p.m.)

- First Call for Dress Parade (5:10 p.m.) and Second Call for dress parade (5:15 p.m.)

- Supper (6:10 p.m.)

- Tattoo (9:00 p.m.) and Taps (9:15 p.m.)

General Order No. 130 directed officers to reduce the amount of baggage they carried with them, allowing each officer only a single carpet bag or valise and a single mess chest. Moving forward, none of their boxes or trunks would be taken aboard baggage trains. In addition, privates would be prohibited from loading boxes onto regimental wagons, as well as from carrying carry carpet bags—while sutlers were banned from using regimental wagons to move their wares from place to place.

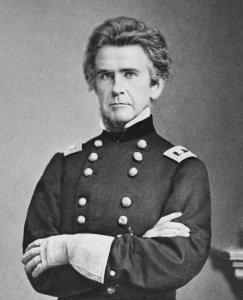

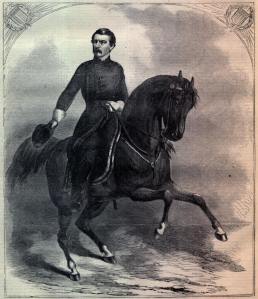

Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the South, circa 1862 (public domain).

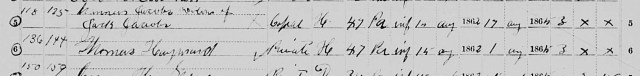

The next week, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers entered into what would become an eventful service period. It began on Monday, September 15 when General Ormsby S. Mitchel arrived at Hilton Head, South Carolina and assumed command of the U.S. Army’s Department of the South. Mitchel then traveled to Beaufort the next day, according to 47th Pennsylvania musician Henry D. Wharton, where he demonstrated “his eagerness to command” as he reviewed all of the troops which made up the brigade serving under Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan.

“In the afternoon at 3 o’clock, the 47th and 55th Pennsylvania Volunteers, 4th New Hampshire, 8th Maine, 1st Massachusetts Cavalry, 1st Connecticut Battery, and the 1st US Artillery were on the drill ground, ready for the reception of their new officer. The 6th Connecticut was not on review, they being on picket. After review, the regiments marched to their different camps, formed in mass, ready to receive the General on his visit to their camps. Ours was the first at which he stopped. He rode in front of the regiment and said:

‘Soldiers, I am with you for the first time. I want you to hear my voice, that you may know it, on the battlefield and at night when you are on guard, so that when you do hear it you may know your General. Where I have been in command every soldier knows me by my voice, even at night, no matter what post I might cross. Discipline is the great requisite of the soldier. Every soldier should be fit to be a non-commissioned officer, none should be satisfied with his grades. A soldier who does nothing for promotion is not fit for a soldier, and a commissioned officer, who is satisfied with his position, will never make a good officer.’

‘Men of the 47th, of the Old Keystone, I trust you. It is impossible for a General, commanding, to know all in his command, nor the men him, but having confidence in you, I know you will act in such a manner that will reflect credit on the glorious state from which you hail. To gain a victory is your aim. There are two kinds of victories: one to meet the enemy and fall in death’s track, and the other to see the backs of the foe, as they try to escape the vengeance of those who are fighting for the most glorious cause and country a soldier can lay down his life for. It is not to be supposed you are to remain inactive. It is not quite time for an advance, but rest assured, you may soon hear the command, ‘Onward!’”

“The boys were very much pleased,” added Wharton, and as Mitchel and Gen. Brannan departed, they “gave such cheers, and a tiger, as Pennsylvanians always give to those in whom they place confidence.”

On Saturday, September 20, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers officially celebrated the one-year anniversary of their service by listening to a reading of Special Order No. 60, which had been issued at Beaufort by their regiment’s founder:

“The Colonel commanding takes great pleasure in complimenting the officers and men of the regiment on the favorable auspices of today.

Just one year ago today, the organization of the regiment was completed to enter the service of our beloved country, to uphold the same flag under which our forefathers fought, bled, and died, and perpetuate the same free institutions which they handed down to us unimpaired.

It is becoming therefore for us to rejoice on this first anniversary of our regimental history and to show forth devout gratitude to God for this special guardianship over us.

Whilst many other regiments who swelled the ranks of the Union Army even at a later date than the 47th have since been greatly reduced by sickness or almost cut to pieces on the field of battle, we as yet have an entire regiment and have lost but comparatively few out of our ranks.

Certain it is we have never evaded or shrunk from duty or danger, on the contrary, we have been ever anxious and ready to occupy any fort, or assume any position assigned to us in the great battle for the constitution and the Union.

We have braved the danger of land and sea, climate and disease, for our glorious cause, and it is with no ordinary degree of pleasure that the Colonel compliments the officers of the regiment for the faithfulness at their respective posts of duty and their uniform and gentlemanly manner towards one another.

Whilst in numerous other regiments there has been more or less jammings and quarelling [sic] among the officers who thus have brought reproach upon themselves and their regiments, we have had none of this, and everything has moved along smoothly and harmoniously. We also compliment the men in the ranks for their soldierly bearing, efficiency in drill and tidy and cleanly appearance, and if at any time it has seemed to be harsh and rigid in discipline, let the men ponder for a moment and they will see for themselves that it has been for their own good.

To the enforcement of law and order and discipline it is due our fame as a regiment and the reputation we have won throughout the land.

With you he has shared the same trials and encountered the same dangers. We have mutually suffered from the same cold in Virginia and burned by the same southern sun in Florida and South Carolina, and he assures the officers and men of the regiment that as long as the present war continues, and the service of the regiment is required, so long he stands by them through storm and sunshine, sharing the same danger and awaiting the same glory.”

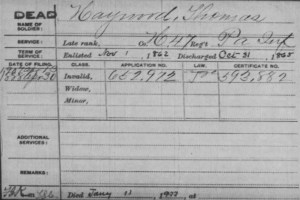

Two days later, the 47th Pennsylvania’s Assistant Surgeon Jacob H. Scheetz, MD was placed in charge of the Union’s General Hospital in Beaufort. (The commander of the 47th Pennsylvania’s medical unit since March 17, 1862 when Regimental Surgeon Baily was assigned to detached duty, Scheetz would continue to direct operations at the Beaufort facility until the 47th Pennsylvania returned to Key West in December 1862.)

Saint John’s Bluff Expedition

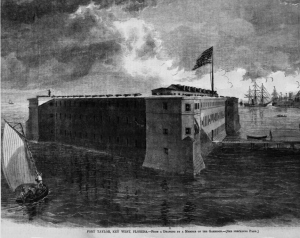

USS Boston (pre-Civil War, public domain).

Then, as September drew to a close, the brisk winds of change began to truly stir when the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and other regiments under Brigadier-General Brannan’s command were ordered to pull together two days’ worth of ammunition and food for a return trip to Florida. Boarding the USS Boston, a 225-foot, 630-ton side wheeler, during the morning of Tuesday, September 30, the 47th Pennsylvanians sailed away around noon, followed by the 7th Connecticut at 2:30 p.m. that afternoon on the Ben DeFord, and sixty members of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry plus two cannons and their operators from the 1st Connecticut Light Artillery, who sailed via the Cosmopolitan. Also joining the expedition was a smaller steamship, the Neptune, which transported surfboats.

Stopping briefly that afternoon at Hilton Head to pick up Brigadier-General Brannan and his staff (who made the Ben DeFord their headquarters for the expedition), the troops were addressed by Major-General Mitchel, urging them to capture as many of the enemy as possible while also destroying or seizing their artillery. “Exceptional glory” was not to be obtained “should the expedition succeed,” he said, but they would be “disgraced” if they failed.

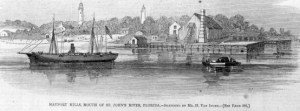

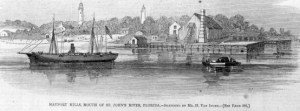

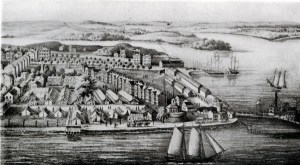

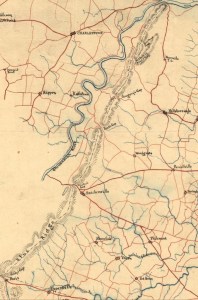

Union Navy’s base of operations, Mayport Mills, circa 1862 (public domain).

The fleet of ships sailed out of Port Royal Bay at 4 p.m. and, after what was described by several of the soldiers involved as “a pleasant voyage” of roughly 140 miles, they reached the mouth of Florida’s St. John’s River at 7 a.m. on October 1. Steaming on to a point opposite Mayport Mills, they were forced to wait for the Darlington, a smaller steamer that had been captured previously from Confederates, to arrive and transport them to shore.

Brannan used the hour to review his troop strength and strategize with Captain Charles E. Steedman. The 1,573 men they commanded were slated to attack a reportedly impregnable Confederate fort atop a nearby bluff (Fort Rickets or Fort Finegan, according to members of the 47th Pennsylvania), which towered 80 feet above the river. That force included the following:

- 47th Pennsylvania (825 men, commanded by Colonel Tilghman H. Good);

- 7th Connecticut (647 men, commanded by Colonel Joseph R. Hawley);

- 1st Connecticut Light Battery (41 men and two cannons from the battery’s left section, commanded by Lieutenant Cannon);

- Hamilton’s Battery (two sections); and

- 1st Massachusetts cavalry (one company of 60 men, commanded by Captain Case).

Waiting for them would be roughly 1,200 Confederate infantry and cavalry—plus artillery.

From Water to Land

Ready to move the troops from steamer to shore by noon on Wednesday, October 1, the Union’s transport ships crossed the St. John’s Bar and entered the river around 2 p.m. The Cimarron, Water Witch, and Uncas were sent upstream toward Sister’s Creek in order to draw enemy fire and shell the fort. Successful in distracting the enemy, those gunboats kept up their efforts for roughly an hour as the Union transports unloaded their passengers downstream.

* Note: Per historian Lewis Schmidt, Mayport Mills was “a small timber village located about two miles up the St. John’s River and four miles as the crow flies east of the fort at the approximate location of present day Mayport which is located along the south bank of the river.”

According to historian Herbert W. Beecher:

“There were two or three large sawmills supplied with gang saws, which gave evidence of cutting a large amount of lumber … a store close by the bank … a Catholic Church and two light houses, one of them a very beautiful and costly structure, nearly new; apparently never having been used … several small cottages, containing three or four rooms, were built on the sand and had most probably been occupied by the lumbermen; they appeared as though they had been standing empty six or seven months. The wind had drifted the white sand about them until some of the drifts were 25 feet high and so compactly made that it was possible for the comrades to walk up the sand drifts and on the roofs of the houses and look down the chimneys … one of the comrades … lighted a pine torch and commenced setting the houses on fire. He was surprised when ordered to stop the deprivation … and was arrested, reported a member of the Connecticut Battery. Mr. Parson, owner of the Mayport Lumber Mills, and one of his negroes was made a prisoner on Thursday morning, but Parson was so thoroughly a Rebel, that no threats could induce him to give information.”

The troop and equipment unloading plan appears to have been somewhat problematic, according to historian Herbert W. Beecher:

“In unloading, the horses were thrown overboard and mostly made for a sand bank about a quarter of a mile from the steamer, but in one or two cases they put out to sea and had to be chased by the boat’s crew in a small boat. In this way one horse was drowned, and Gen. Brannan’s horse had its leg broken and had to be killed…. It was late that night before the Cosmopolitan was unloaded and the companies had to remain on the bank among the sand hills all night….

The scouts reported that the infantry could land at place known as Buckhorn Creek, between Pablo and Mount Pleasant Creeks… A portion of the troops were taken under protection of the gunboats, to Buckhorn Creek on the mainland … and landed at 2 o’clock on the morning of the 2nd … between Pablo and Mount Pleasant Creeks … and if possible they were to capture the enemy….

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, under Col. Good, immediately threw out skirmishers, and the advance commenced, but had proceeded hardly a mile when they came suddenly upon an unfordable creek, and were compelled to return to Mayport Mills, when it was decided to re-embark the troops on the flats.”

Military reports of the 47th Pennsylvania’s landing described a more efficient process, however; Colonel Good, the 47th’s commanding officer, stated that “at 9 PM Lt. Cannon reported to me that his command, consisting of one section of the 1st Connecticut Battery, was then coming up the creek on flat boats with a view of landing.”

“During the night … at 4 a.m. a safe landing was effected … the artillery was brought up in surf boats and landed at the point where we lay…. The order to move to St. John’s Bluff reached me at 4 p.m. yesterday…. The night passed pretty peacefully and we all excitedly awaited to see what would happen when the time came for the main engagement…. A few rebels came into our camp and insisted on going along with us, and also a few cattle we took along, which we slaughtered and divided among the companies.”

H Company First Lieutenant William Wallace Geety described “standing picket that night until 12 when I laid down and slept soundly. We were reinforced that night by cavalry and artillery.”

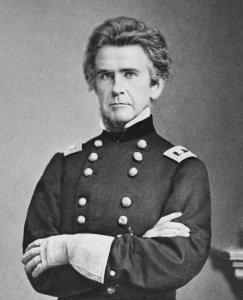

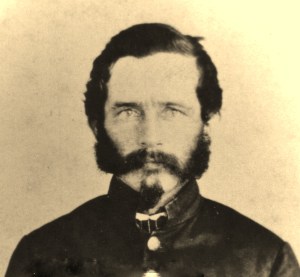

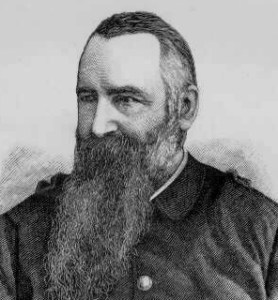

Captain Henry Durant (“H.D.”) Woodruff, commanding officer of Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (public domain).

Captain Henry Durant Woodruff, the commanding officer of the 47th Pennsylvania’s D Company, recalled that:

“Between this point of land and the fort was an extensive swamp and lagoon, which we could not cross, and to reach the fort from this point we would have to march around forty miles. This we concluded not to do. We waited til night, re-embarked, unloaded our surf boats.”

* NOTE: According to Schmidt, the landing was effected where the Buckhorn Creek “intersects the Intercoastal Waterway and Pablo Creek at Chicopit Bay, about two miles upriver from Mayport…. The attempted approach was made through marsh and swamp and when the troops reached Greenfield Creek, the route became totally impassable and they were unable to reach a point where the fort could be approached from the rear or southern side.”

Also, per Woodruff:

“The ground was altogether too swampy for either cavalry or artillery to land at that point; the artillery was ordered to reload on a light draught steamer and flatboats and proceed up a winding creek to a point in the marsh where it was more practicable to land. The gunboats were called into requisition to transport the infantry, in their boats, to the land and to send their light howitzers to cover the landing. The entire force of the infantry and marine howitzers proceeded up the river a little distance and landed at the head of Mount Pleasant Creek, where Col. Good established a strong position to cover the landing of the artillery and cavalry….

We found five gunboats in the river. They had attempted the reduction of the fort, but had been repulsed. The only remedy left was for our small force to land and take it by storm; and the only place we could land was under the guns of the fort. Consequently we had recourse to strategy. We landed in full sight of the fort, on a point of land at the mouth of the river, out of reach of their guns….

Landing at our destination about 6 a.m. right in one of those great Florida swamps and marshes, among rattlesnakes, copperheads, centipedes, alligators, and many other poisonous reptiles and insects. We were informed that the natives never dare venture into that swamp, except in mid-winter, and even then they selected the coldest days when no sun was shining. The cook and his assistant selected a spot to make the coffee; it was near a large palmetto jungle. I well remember, when just as the fire was burning nicely, out crawled a huge rattlesnake from the palmetto grove. The heat of the fire had roused him from his lethargic sleep and the aromatic fragrance of the coffee was too much for him. Everyone who saw the reptile had a shot at him with pistols, making him surrender very quickly. He measured nine feet in length and had ten rattles. In his death struggles he emitted an odor, a sort of sickening musk, that scented the entire camp.”

As all of this was taking place, Brigadier-General Brannan was sailing up the river aboard the gunboat Paul Jones with additional troops following on the Cimarron and Patroon. Conducting reconnaissance, they also shelled the woods to the left and right.

“Col. Good and his 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched for the bluff,” early Thursday morning according to Schmidt, “with the help of a Black man named Israel, a contraband who served as Good’s guide. They headed for Parker’s Plantation.” The day unfolded as follows, per Good’s report to his superiors:

“HEADQUARTERS U.S. FORCES

Mount Pleasant Landing, Fla. October 2, 1862.

SIR: I have the honor to make the following report for the information of the general commanding:

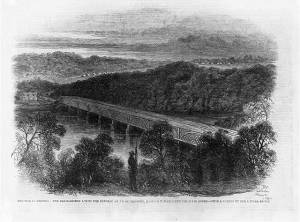

In accordance with orders received I landed my regiment on the bank of Buckhorn Creek at 7 o’clock yesterday morning. After landing I moved forward in the direction of Parker’s plantation, about 1 mile, being then within about 1¼ miles of said plantation. Here I halted to await the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut Regiment. I advanced two companies of skirmishers toward the house, with instructions to halt in case of meeting any of the enemy and report the fact to me. After they had advanced about three-quarters of a mile they halted and reported some of the enemy ahead. I immediately went forward to the line and saw some 5 or 6 mounted men about 700 or 800 yards ahead. I then ascended a tree, so that I might have a distinct view of the house, and from this elevated position I distinctly saw one company of infantry close to the house, which I supposed to number about 30 or 40 men, and also some 60 or 70 mounted men. After waiting for the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut Volunteers until 10 o’clock, and it not appearing, I dispatched a squad of men back to the landing for a 6-pounderfield howitzer which had been kindly offered to my service my Lieutenant Boutelle, of the Paul Jones. This howitzer had been stationed on a flat-boat to protect our landing. The party, however, did not arrive with the piece until 12 o’clock, in consequence of the difficulty of dragging it through the swamp. Being anxious to have as little delay as possible, I did not await the arrival of the howitzer, but at 11 a.m. moved forward, and as I advanced the enemy fled. After reaching the house I awaited the arrival of the Seventh Connecticut and the howitzer. After they arrived I moved forward to the head of Mount Pleasant Creek to a bridge, at which place I arrived at 2 p.m. Here I found the bridge destroyed, but which I had repaired in a short time. I then crossed it and moved down on the south bank toward Mount Pleasant Landing. After moving about 1 mile down the bank of the creek my skirmishing companies came upon a camp which evidently had been very hastily evacuated, from the fact that the occupants had left a table standing with a sumptuous meal already prepared for eating. On the center of the table was placed a fine, large meat pie still warm, from which one of the party had already served his plate. The skirmishers also saw 3 mounted men leave the place in hot haste. I also found a small quantity of commissary and quartermaster’s stores, with 23 tents, which, for want of transportation, I was obliged to destroy. After moving about a mile farther on I came across another camp, which also indicated the same sudden evacuation. In it I found the following articles, viz: Eighteen Hall’s breech-loading carbines, 12 double-barreled shot-guns, 8 breech-loading Maynard rifles, 11 Enfield rifles, and 96 knapsacks. These articles I brought along by having the men carry them. There were, besides, a small quantity of commissary and quartermaster’s stores, including 16 tents, which, for the same reason as stated, I ordered to be destroyed. I then pushed forward to the landing, where I arrived at 7 p.m.

We drive the enemy’s skirmishers in small parties along the entire march. The march was a difficult one, in consequence of meeting so many swamps almost knee-deep.

I am, sir, your obedient servant,

T. H. GOOD,

Colonel Forty-seventh Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers.

Captain LAMBERT,

Assistant Adjutant-General”

* NOTE: Among the initial group of skirmishers from the 47th Pennsylvania was F Company Private George Klein. In a letter (transcribed from its original German by historian Lewis Schmidt), Klein noted that his “company put out skirmishers, and the first platoon which I belonged to, one Lieutenant and 28 men, went toward the first house we saw.”

“Our guide was an intelligent colored man [Israel] and we wanted to catch a secesh. We did get to catch a band of guerillas at the house who were watching to see what the Yankees had on their mind, and they pulled back when they saw us. We took them a piece back and handed them over to the officers, and they were put on the steamer and guarded. Still, there was one white man, three daughters or cousins, and three old [enslaved men] in the house. The ladies were getting excited when we got near the house and they were pretty and wondering what the Yankees were going to do to the devotees of Uncle Jeff. Perhaps the night before they had a nice dream about King Cotton’s future. That was reason enough to cry and weep. But it did not bother us, we grabbed our prey and got back to camp without trouble.”

Good then offered further insight via a follow-up report:

“HEADQUARTERS U.S. FORCES

Saint John’s Bluff, Fla., October 3, 1862.

SIR: For the information of the general commanding I have the honor to make the following report:

At 9 o’clock last night Lieutenant Cannon reported to me that his command, consisting of one section of the First Connecticut Battery, was then coming up the creek on flat-boats with a view of landing. At 4 o’clock this morning a safe landing was effected and the command was ready to move. The order to move to Saint John’s Bluff reached me at 4 p.m. yesterday. In accordance with it I put the column in motion immediately and moved cautiously up the bank of the Saint John’s River, the skirmishing companies occasionally seeing small parties of the enemy’s cavalry retiring in our front as we advanced. When about 2 miles from the bluff the left wing of the skirmishing line came upon another camp of the enemy, which, however, in consequence of the lateness of the hour, I did not take time to examine, it being then already dark.

After my arrival at the bluff, it being then 7:30 o’clock, I dispatched Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander with two companies back to the last-named camp (which I found, from a number of papers left behind, to have been called Camp Hopkins and occupied by the Milton Artillery, of Florida) to reconnoiter and ascertain its condition. Upon his return he reported that from every appearance the skedaddling of the enemy was as sudden as in the other instances already mentioned, leaving their trunks and all the camp equipage behind; also a small quantity of commissary stores, sugar, rice, half barrel of flour, one bag of salt, &c., including 60 tents, which I have brought in this morning. The commissary stores were used by the troops of my command.

I have the honor to be, your obedient servant,

T. H. GOOD,

Colonel Forty-seventh Regiment Pa. Vols., Comdg.

Captain LAMBERT,

Assistant Adjutant-General.”

* NOTE: Private Brecht recalled the expedition (in another letter, which was translated from the original German by Schmidt):

“It was an unusual day for us on the way, always through bush, marsh, swamp and water and a few times we were under water and in much rain. We worked through with sixty bullets per man on the side, and five days rations on the back, but we made it. Col. Good was at the head of the regiment on foot, and was strong and happy, and even the Connecticut Regiment could not keep up with us and were always a good piece behind. Before we reached out camping place we passed two rebel camps which we could see were abandoned in a hurry, one left his hat and one left his saber. Because of the swampy terrain, the horses could not follow us….

The enemy’s camps were utterly destroyed…. The tents, and those things we could not carry, we destroyed…. After destroying the marques [tents], mostly all new and numbering some seven or eight, we pushed on again under the guidance of a negro, who escaped from the fort but four weeks previous…. The country soon became marshy after leaving the last camp, and it was found necessary to build a corduroy road for the howitzer accompanying the land force. This unlooked for circumstance detained our troops some time…. Night came upon us. I then pushed forward to the landing, where I arrived at 7 PM … we moved to the river bank to bivouac for the night under the cover of gunboats … we made camp one mile below the fort … in the bushes for night…. Col. Good was in command all day. The march was a difficult one, in consequence of meeting so many swamps almost knee deep… it rained all day and much of our way was through swamps. I was glad to stop and get hot coffee and dry stockings.’ [Good] ‘sent to the General and asked permission to storm the fort that night. The General refused, as the cavalry and artillery had not been landed. So we bivouacked that night on the shore of the St. John….”

Earthen works surrounding the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff, Saint John’s River, Florida, 1862 (J. H. Schell, public domain).

While First Lieutenant Geety confirmed that:

“16 pieces of artillery were left ready loaded, primed, with the lanyards hooked to the primers ready to pull.’ He also included with his memorabilia a ‘roster of the rebel troops stationed about St. John’s River, Florida, taken at the camp of the Louisiana Tigers, who with another rebel regiment guarded the rear approaches of the rebel fort. They ran leaving all their camp and garrison equipage and their suppers on the fire which our men ate…. The rebels had 1500 men, six pieces of light artillery besides the nine pieces at the fort and a impregnable position. The rebels were not uniformed and have rice, corn, and fresh meat; coffee and flour only allowed those in the hospital; salt they had little or none of, it being worth $1 per quart; sugar they had plenty of.”

Penning his own recap, Brigadier-General Brannan estimated that the Confederate equipment captured by Union troops was worth more than two hundred thousand dollars and included: two eight-inch columbiads, two eight-inch howitzers, two eight-inch, smooth bore guns, two 4.6-inch rifled cannon, $15,000 worth of shot and shell, multiple small arms, and more than two hundred tents. Brannan later explained that he “left the work of removing the guns from St. John’s Bluff to Col. T.H. Good, 47th Regiment Pennsylvania Volunteers, my second in command.”

One of the most detailed recaps, however, was apparently penned in Port Royal, South Carolina on Tuesday, October 14, 1862 by 47th Pennsylvanian Henry D. Wharton after Brigadier-General Brannan and his troops had returned from Florida to Hilton Head. Wharton’s report was subsequently distributed via several publications nationwide, including the October 20 edition of The New York Times and Wharton’s hometown newspaper:

“The expedition left Hilton Head on the afternoon of the 30th ultimo, consisting of the Pennsylvania Forty-seventh Regiment, Col. GOOD; the Connecticut Seventh Regiment, Col. HAWLEY; a section of the First Connecticut Battery, under Lieut. CARMON, and a detachment of the First Massachusetts Cavalry under Capt. CASE, making a total effective force of 1,573. The troops were embarked on the steamers Ben Deford, Boston, Cosmopolitan and Neptune, and arrived off the bar of the St. John’s River early on the morning following their departure, but were unable to enter the river until 2 P.M. in consequence of the shallowness of the channel. There the expedition was joined by the gunboats Paul Jones, Capt. STEEDMAN, commanding the fleet; Cameron, Capt. WOODHULL; Water Witch, Lieut.-Com. PENDERGRAST; E. B. Hait, Lieut.-Com. SNELL; Uncas, Lieut.-Com. CRANE, and the Patroon, Lieut.-Com. Urano. The same afternoon three gunboats were sent up to feel the position of the battery on the Bluff, and were immediately and warmly engaged, the enemy apparently having a number of heavy guns in his works.”

Wharton went on, noting that the troops disembarked “at a place known as Mayport Mills, situated a short distance from the entrance of the river,” and added that “all the men, rations and arms were on shore by 9 o’clock on the evening of the 1st.”

“The country between this point and St. John’s Bluff presented great difficulties in the transportation of troops, being intersected with impassable swamps and unfordable creeks, and presenting an alternative of a march of forty miles without land transportation, to turn the head of the creek, or to reland [sic] up the river at a strongly-guarded position of the enemy. On further search, a landing place was found for the infantry at about 2 o’clock on the morning of the 2d, at a place called Buckhorn Creek, between Pable and Mount Pleasant Creeks, but the swampy [nature] of the ground made it impracticable to land the cavalry and artillery at that point. The gunboats here rendered valuable assistance by transporting troops and sending light howitzers in launches to cover the landing.”

According to Wharton, the 47th Pennsylvania’s commanding officer, Col. Good, was ordered to lead “the entire infantry and … howitzers … immediately forward to the head of Mount Pleasant Creek, to secure a position to cover the landing of the cavalry and artillery.”

“The movement was executed skillfully, surprising and putting to flight the rebel pickets on that creek. This rapid movement to Mount Pleasant Creek, and the landing of the troops at Buckhorn Creek, was very fortunate as it seemed to disarrange the enemy’s plan, if he had any, to prevent our disembarkation. Their pickets retired in such haste and trepidation as to leave their camps standing, their arms, and even a great portion of their clothing behind them, and only escaped themselves because of the intricate character of the ground and their superior knowledge of the country.”

The next afternoon (October 3), “the artillery and cavalry were in readiness at the head of Mount Pleasant Creek, two miles from the enemy’s batteries at St. John’s Bluff.” Wharton and more senior military men estimated the number of Confederate cavalrymen and infantrymen who opposed them that day at 1,200 in addition to the artillery batteries, which reportedly contained “nine heavy pieces.”

“Under these circumstances, Gen. Brannan deemed it expedient, in consultation with Capt. Steedman, to send the Cosmopolitan to Fernandina for reinforcements from the garrison of that place, and three hundred of the Ninth Maine Regiment were sent down on the following morning.”

Later in the day on October 3, according to Wharton, Brannan directed Steedman to send out three gunboats “to feel the position of the enemy, shelling them as they advanced, when the batteries were found to be vacated, and Lieut. Snell, of the Hale, sent a boat on shore and raised the American flag, finding the rebel flag in the battery. The naval force then retained possession, until the arrival of the troops, who immediately advanced…. On approaching the enemy’s position on the Bluff, it was found to be of great strength, possessing a heavy and effective armament, consisting of two eight-inch columbiads, two eight-inch siege howitzers, two eight-inch seacoast howitzers, and two rifled guns, supplied with ammunition in abundance, shot, shell, tools and camp equipage.”

“The works were skillfully and carefully constructed, and the strength of the position was greatly enhanced by the natural ground, it being only approachable on the land side, through a winding ravine immediately under the guns of the position, and, from the narrowness of the river and the elevation of the Bluff, rendering fighting by the gunboats most difficult and dangerous. Most of the guns were mounted on complete traverse circles, and, indeed, taking everything into consideration, there is no doubt that a small party of determined men might have maintained the position for a considerable time against even a larger force than we brought against it.”

But Brannan and Good’s men weren’t quite done, yet, with the Confederates in that region.

Next up? Entering Jacksonville, the capture of a Confederate steamer, and the integration of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry with the enlistment of several formerly enslaved Black men.

Sources:

- Beecher, Herbert W. History of the First Light Battery Connecticut Volunteers, 1861-1865, Vol. I. New York, New York: A. T. De La Mare Ptg. and Pub. Co., Ltd., 1901.

- “Important From Port Royal; The Expedition to Jacksonville, Destruction of the Rebel Batteries. Capture of a Steamboat. Another Speech from Gen. Mitchel. His Policy and Sentiments on the Negro Question.” New York, New York: The New York Times, October 20, 1862.

- Reports of Lieut. Col. Tilghman H. Good, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania Infantry, in Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 1861-1865 (Microfilm M262). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Wharton, Henry D. Letters from the Sunbury Guards. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1862.

You must be logged in to post a comment.