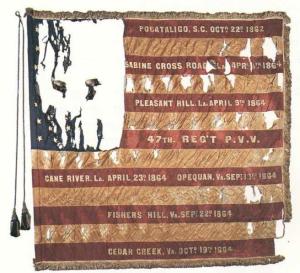

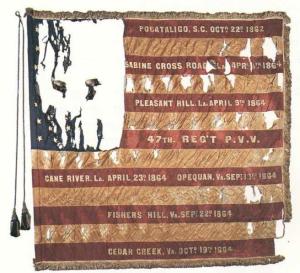

Second State Colors, 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers (presented to the regiment 7 March 1865).

Seven battle names embossed on a battle flag. Three documented a series of seemingly minor military engagements during one oft-maligned military campaign of the American Civil War.

Known by military scholars today as the 1864 Red River Campaign, those “minor” engagements ensured that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would be known for all time as history makers—members of the only regiment from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to take part as the Union’s Army of the Gulf marched through Louisiana between late February and mid-July 1864, enabling the United States government to prevent the war and the brutal practice of chattel slavery from spreading any further west.

As for how inconsequential those “minor” engagements of the 1864 Red River Campaign were? They left such indelible marks on the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry that its senior officers chose to emboss the majority of that campaign’s battle names on the second battle flag that was carried by the regiment as it defended the nation in the wake of President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865, and as the regiment marched triumphantly through the streets of Washington, D.C. during the Union’s Grand Review of the Armies in late May of that same year.

How It Began

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ participation in the 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana began with a series of general and special orders and other communications that were issued by senior military officers of the United States Army:

- SPECIAL ORDERS, No. 39

HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE GULF, New Orleans, Louisiana, February 13, 1864.

12. First. The Second Regiment U.S. Colored Troops will be relieved from duty at Ship Island and proceed without delay to Key West, Fla., where it will be reported for duty to Brig. Gen. D. P. Woodbury. Second. On the arrival of the Second U.S. Colored Troops at Key West, the battalion of Forty-seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers stationed at that point will be relieved from duty in the District of Key West and Tortugas, and will proceed without delay to Franklin, La., where it will be reported for duty to Maj. Gen. W. B. Franklin, commanding Nineteenth Army Corps. Third. On the arrival of the First Battalion, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, at Franklin, the One hundred and tenth New York Volunteers will proceed to Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, and relieve the battalion of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania now in garrison there. Fourth. On being so relieved, the battalion of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania now stationed at Fort Jefferson will proceed to Franklin, La., and report for duty at the headquarters of the regiment. The quartermaster’s department will immediately furnish the necessary transportation.

By command of Major-General Banks:

RICHD. B. IRWIN,

Assistant Adjutant-General.

- SPECIAL ORDERS, No. 48

HEADQUARTERS 19th ARMY CORPS AND U.S. FORCES, Franklin, Louisiana, February 18, 1864.

5. In pursuance of Special Orders No. 41, extract 3, current series, headquarters Department of the Gulf, the following-named regiments assigned to the First Division, Nineteenth Army Corps, Brig. Gen. W. H. Emory commanding, are hereby assigned to brigades as follows, to take effect February 20, 1864:First Brigade, to be commanded by Brig. Gen. William Dwight: Fifteenth Maine, Thirtieth Massachusetts, One hundred and fourteenth New York, One hundred and seventy-third New York, One hundred and sixty-first New York.Second Brigade, to be commanded by Brig. Gen. J. W. McMillan: Twenty-sixth Massachusetts (temporary), Thirteenth Maine, Twelfth Connecticut, Eighth Vermont, One hundred and sixtieth New York, Forty-seventh Pennsylvania.Third Brigade, to be commanded by the senior colonel: Fourteenth Maine, One hundred and sixty-second New York, One hundred and sixty-fifth New York, One hundred and sixteenth New York, Thirtieth Maine.

Capt. Duncan S. Walker, assistant adjutant-general, U.S. Volunteers, is assigned to duty as assistant adjutant-general, First Division, and will report to Brigadier-General Emory.

Capt. Oliver Matthews, assistant adjutant-general, U.S. Volunteers, is assigned to duty as assistant adjutant-general, First Brigade, First Division, and will report to Brig. Gen. William Dwight.

The following-named batteries are assigned to the First Division: Battery A, First U.S. Artillery; Battery L, First U.S. Artillery; Fourth Massachusetts Battery, Sixth Massachusetts Battery, Twenty-fifth New York Battery.

By order of Major-General Franklin:

WICKHAM HOFFMAN,

Assistant Adjutant-General.

- HEADQUARTERS, DEPARTMENT OF THE GULF, New Orleans, Louisiana, February 19, 1864.

Major-General Franklin, Commanding, Nineteenth Corps, Franklin:

GENERAL: Instead of awaiting the arrival of the battalion of the Forty-seventh Pennsylvania Volunteers, as heretofore ordered, the One hundred and tenth New York Volunteers will be immediately relieved from duty with the First Division, Nineteenth Army Corps, and will proceed without delay to Algiers, where it will take steam transportation for Key West, Fla.

By command of Major-General Banks:

RICHD. B. IRWIN,

Assistant-Adjutant General.

How It Progressed

Casualties began to be incurred by the 47th Pennsylvania even before members of the regiment stepped off of their respective troop transports and onto Louisiana soil in early March 1864. Researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story believe that the first Red River casualty was actually Private Frederick Koehler, who reportedly drowned after falling overboard from his transport, just as it was entering the harbor near Algiers, Louisiana.

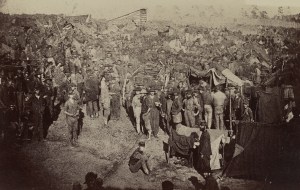

From that moment on, the regiment’s casualty rate climbed as the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers marched, built, dug, and fought their way across unfamiliar, difficult terrain, under conditions for which their northern bodies and immune systems were ill prepared. Two of the campaign’s engagements—the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield on April 8, 1864, and the Battle of Pleasant Hill on April 9—were among the most brutal and sanguinary fighting that they waged during the entire war.

Along the way, the 47th Pennsylvanians helped to free more Black men, women and children from the plantations where they had long been enslaved, with five of the men they met ultimately choosing to enlist with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, further integrating a regiment that had already begun enrolling Black soldiers as far back as the fall of 1862.

How It Ended

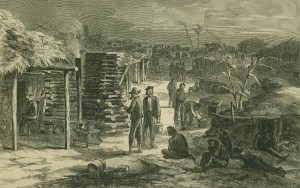

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Their final combat engagement—the Battle of Mansura—was fought on May 16, 1864. Afterward, they marched for Morganza, Louisiana. Encamped there for most of June, they finally made their way back to New Orleans by the end of that month—two campaign-ending duty stations that were not luxurious by any standards now, or then, but were far more comfortable than what they had endured throughout their long and difficult spring.

Those final duty stations were still not completely safe for them, however; the grim reaper continued to scythe men left and right as typhoid, mysterious fevers, dysentery, and chronic diarrhea ravaged the regiment during the unbearably hot, humid weeks of June and early July.

As a result, the regiment lost as many or more of its members to disease than it did to the rifle and cannon fire that they had so recently dodged. And the war was still not over.

When the Fourth of July arrived for the weary warriors, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were busy packing their belongings, having just received new orders to return to the Eastern Theater of battle. By mid-July, roughly sixty percent of the regiment’s members were fighting for their lives yet again—this time in the Battle of Cool Spring, near Snicker’s Gap, Virginia.

As that was happening, multiple members of the regiment were coming to grips with the fact that they had been left behind to recuperate from battle wounds or diseases they had contracted while in service to the nation. Among those convalescents were eighteen men who subsequently died at Union hospitals or Confederate prison camps long after their comrades had reached the East Coast. Two of those men were later documented as among the five total who died in Baton Rouge, with ten men among the total of thirty-three who passed away in New Orleans. Seven others died in Natchez, Mississippi, and at least one of the men left behind had been one of the seventeen POWs held captive at Camp Ford, the largest Confederate prison camp west of the Mississippi River.

Stilled Voices

The phrase, “Dum Tacent Clamant” (While they are silent, they cry aloud”), is inscribed on the Grand Army of the Republic monument at the Chalmette National Cemetery in St. Bernard Parish, Louisiana, where multiple members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers remain at rest (G.A.R. Monument, Chalmette National Cemetery, circa 1910, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

More than seventy of the 47th Pennsylvania’s disease and battle-related casualties remain at rest in marked or unmarked national cemetery graves in Louisiana and Mississippi. Other unsung heroes lie forgotten in graves yet to be identified, part of the legion of American soldiers “known but to God.”

Albert, George Washington: Corporal, Company H; fell ill during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to a Union Army hospital; discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability on April 18, 1864, he died aboard the U.S. Steamer Yazoo while being transported home to Pennsylvania to convalesce; buried at sea, a cenotaph was created for him at Ludolph’s Cemetery in Elliottsburg, Pennsylvania;

Andrew, Michael: Private, Company A; fell ill with chronic diarrhea sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to a Union Army general hospital; died there on July 15 or 18, 1864; was interred at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Barry, William: Private, Company H; killed in action during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield, Louisiana on April 8, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Beidleman, Jacob (alternate surnames: Beiderman, Biedleman): Private, Company G; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was confined to the Union’s hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, and transported to Natchez, Mississippi, where he was confined to Union Army’s Natchez General hospital; died there on July 3, 1864; may have been interred at the Natchez National Cemetery in a grave that remains unidentified;

Bellis (alternate spelling: Bellus), Amandus: Private, Company A; fell ill during the Red River Campaign, was confined to the Union’s hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, while it was docked near Morganza, Louisiana; subsequently transported to Natchez, Mississippi, he died en route, while aboard that ship, on June 30, 1864; was possibly buried at sea or interred in an unmarked grave at the Natchez National Cemetery that remains unidentified;

Berlin, Elias: Private, Company A; fell ill in Florida, or during the opening days of the Red River Campaign; died in Florida, or aboard ship while en route to Louisiana, or in Louisiana on March 28, 1864; was interred, or a cenotaph was created for him, at the Zion UCC Stone Church Cemetery in Kreidersville, Pennsylvania;

Bettz, Godfrey (alternate spelling: Betz): Private, Company F; fell ill with chronic diarrhea sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to a Union Army general hospital; died there on May 8, 1864; was interred in section 51, grave no. 3968 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Bohan, George (alternate spellings: Bohan, Bohn, Bollan, Bolian): Private, Company A; fell ill with chronic diarrhea sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to a Union Army general hospital; died there on June 27 or 28, 1864; was interred in section 67, grave no. 5358 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Brader, Josiah (alternate spelling: Braden): Private, Company B; fell ill with typhoid fever sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the University Hospital; died there on July 9, 1864; was interred in section 66, grave no. 5279 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Brooks, George W.: Private, Company E; fell ill with chronic diarrhea sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to a Union Army hospital; died there on August 12, 1864; was interred in section 67, grave no. 5383 at the Monument Cemetery (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Clewell, Jr., Joseph: Private, Company G; fell ill with chronic diarrhea after being captured by Confederate troops during the Battle of Sabine Crossroads/Mansfield on April 8, 1864 or the Battle of Pleasant Hill on April 9, or during one of the regiment’s subsequent Red River Campaign engagements; was subsequently confined to the Confederate States Army hospital in Shreveport, Louisiana sometime in May or early June and held there as a prisoner of war (POW) until his death there on June 18, 1864; possibly interred in one of the unmarked graves in Shreveport’s Greenwood Cemetery, according to Joe Slattery, Genealogy Library Specialist at the Shreve Memorial Library in Shreveport; if not, his remains may have been exhumed and reinterred in an unmarked grave at the Alexandria National Cemetery in Pineville, Louisiana, according to historian Lewis Schmidt;

Crader, James: Sergeant, Company G; fell ill sometime during the Red River Campaign; was confined to the Union’s hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, and transported to Natchez, Mississippi, where he was confined to the Union’s General Hospital in Natchez; died there on July 9, 1864; may have been interred at the Natchez National Cemetery;

Davenport, Valentine: Private, Company H; fell ill during the opening days of the Red River Campaign; was confined to a Union hospital in New Orleans and then discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability on March 28, 1864; died in New Orleans on May 4, 1864; was buried at a national cemetery in the State of New York, according to the U.S. Army Department of the East’s Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers Who Died in Defence of the American Union, Vol. X: “Soldiers Buried in the Department of the East: New York,” p. 15 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1867);

Dech, Alpheus (alternate presentations of name: Alfred Dech, Alpheus Deck): Private, Company G; fell ill with chronic diarrhea sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the U.S. Marine Hospital; died there on June 3, 1864; was interred in grave no. 4028 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Dumm, William F. (alternate spellings: Drum or Drumm): Private, Company H; killed in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Evans, John: Private, Company H; fell ill with chronic diarrhea sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to a Union Army hospital; died there on June 20, 1864; was interred in section 51, grave no. 4042 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Fetzer, Owen: Private, Company I; fell ill with chronic diarrhea sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was hospitalized at the Union’s St. Louis General Hospital; died there on April 19, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Fink, Edward: Private, Company B; declared missing in action (MIA) after the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was later declared as killed in action (KIA), having been killed by gunshot during the battle; his burial location remains unidentified;

Frack, William: Corporal, Company I; declared missing in action and “supposed dead” following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was ultimately declared as killed in action; his burial location remains unidentified;

Gerrett, Mathias (alternate spelling: Garrett): Private, Company K; fell ill with typhoid fever sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the Union Army’s Barracks Hospital; died there on May 22, 1864; was interred in section 51, grave no. 3995 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Haas, Jeremiah: Private, Company C; killed in action during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield, Louisiana on April 8, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Hagelgans, Nicholas: Private, Company K; killed in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Hahn, Richard: Private, Company E; killed in action by a musket ball during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Hangen, Washington H. R.: First Lieutenant and Regimental Adjutant; officially discharged from the U.S. Army and 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry during the summer of 1864; remained in Louisiana, where he worked for the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands (the “Freedmen’s Bureau”) in St. Tammany Parish and Washington Parish before becoming a surveyor for the State of Louisiana and the U.S. Office of the Surveyor General; died in Abita Springs, St. Tammany Parish on April 23, 1895; was likely interred at the Madisonville Cemetery in St. Tammany Parish, where his second wife had previously been buried;

Hart, J. S. (alternate spelling: Harte): Private, Company C; fell ill with chronic diarrhea sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the Marine Hospital; died there on August 5, 1864; was interred in section 49, grave no. 3869 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Hartshorn, John (alternate spelling: Hartshorne): Private, Company H; initially listed as missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, Union Army officials determined he had been captured by Confederate troops and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864; subsequently died at a Union Army hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana on August 8, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Hawk, David C. (alternate spellings: Hank, Hauk): Private, Company I; fell ill with chronic diarrhea sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to a U.S. Army general hospital; died there on July 28, 1864 (alternate death date: July 28, 1865); was described on regimental muster rolls as “absent sick left in U.S. General Hospital of New Orleans since 9-20-64”; was interred in section 49, grave no. 3849 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Helfrich, John Gross: Sergeant, Company C; fell ill with dysentery sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to Charity Hospital; died there on August 5, 1864; was interred in section 49, grave no. 3867 of the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Heller, Jonathan: Private, Company G; fell ill with dysentery sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to Charity Hospital; died there on June 7, 1864; was interred in square 13, grave no. 1 of the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Herbert, Jacob: Private, Company A; fell ill or was injured sometime during the Red River Campaign; was transported to Natchez, Mississippi, where he was confined to a Union Army hospital; died in Natchez on June 30, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Herman, William: Private, Company F; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was confined to the Union Army hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, and transported to Natchez, Mississippi, where he was confined to the Union’s Natchez General Hospital; died there on July 23 or 24, 1864 (his wife’s affidavit in her widow’s pension application notes the date as 23 July; the U.S. Army’s death ledger indicates the date of death was 24 July 1864); may have been interred at the Natchez National Cemetery in Natchez, Mississippi;

Hettrick, Levinus (alternate presentations of name: Levenas Hedrick, Gevinus Hettrick, Levinas Hetrick, Sevinas Hettrick): Private, Company B; drowned in the Mississippi River on June 27, 1864, while serving with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers at Morganza, Louisiana, following the 47th’s participation in the Red River Campaign; his burial location remains unidentified;

Hoffman, Nicholas: Private, Company A; fell ill with typhoid fever sometime during the Red River Campaign; was confined to the Union’s hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, while it was docked near Morganza, Louisiana, and was transported to Natchez, Mississippi; died aboard that ship on June 30, 1864, while it was in the vicinity of Natchez; per an affidavit filed on June 19, 1865 by Sergeant Charles Small and Private Joseph A. Rogers of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, Hoffman was buried at the Natchez National Cemetery in Mississippi;

Holsheiser, Lawrence (alternate spellings of surname: Holsheiser, Holyhauser, Hultzheizer, Hultzheizor): Private, Company F; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the Barracks Hospital; died there on May 1, 1864; was interred at the Monument Cemetery (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Hower, Phillip (alternate spelling: Philip): Private, Company G; contracted Variola (smallpox) during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the Union’s Barracks Hospital; died there on April 21, 1864; was interred at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Keiser, Uriah: Private, Unassigned Men; fell ill during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the Union’s Barracks Hospital; died there in July 1864; was interred at the Monument Cemetery in section 57, grave no.: 4477 (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Kennedy, James: Private, Company C; sustained gunshot fracture of the arm and gunshot wound to his side during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was transported to the Union Army’s St. James Hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he died from his battle wounds on April 27, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Kern, Samuel M.: Private, Company D; wounded in action and captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was marched or transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held in captivity as a prisoner of war (POW) until he died on June 12, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Knauss, Elwin (alternate spellings: Knauss, Kneuss, Knouse; Ellwin, Elvin): Private, Company I; fell ill while during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the U.S. Marine Hospital; died there on August 3, 1864 (alternate death date: June 30, 1864); was interred in grave site 20-55 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Koehler, Frederick (alternate spellings: Koehler, Kohler, Köhler): Private, Company K; was likely the regiment’s first casualty during the Red River Campaign; while sitting in one of the side hatches of the steamship transporting the 47th Pennsylvania to Louisiana, he fell overboard from the ship as it was rounding into port at Algiers and drowned; members of the regiment reported seeing his body “come up astern of the boat,” and that someone had retrieved his cap, which carried the label “F. K.” on its vizier; researchers have not been able to determine whether or not this soldier was buried at sea, at a cemetery in Louisiana, or if his body was returned home for burial in Pennsylvania;

Kramer, George: Private, Company C; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was likely confined to one of the Union Army’s general hospitals in Baton Rouge or New Orleans, Louisiana, or to a Union general hospital in Natchez, Mississippi; was placed aboard the Union’s hospital ship, the SS Mississippi; died aboard that ship on August 27, 1864 and was likely buried at sea or possibly at a still-unidentified cemetery in Louisiana or Mississippi; his name was included on the roster of soldiers listed on the Company C, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ Soldiers Monument that was erected at the Sunbury Cemetery in Sunbury, Pennsylvania;

Lehr, Charles (alternate spelling: Lear): Private, Company A; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was confined to the Union Army’s hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, and was transported to the Union’s Natchez General Hospital in Natchez, Mississippi; died there on July 22, 1864; may have been interred in an unmarked/unknown grave at the Natchez National Cemetery;

Long, Solomon: Private, Company K; Contracted typhoid fever during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the U.S. Marine Hospital; died there on August 21, 1864; was interred in section 60, grave no. 4728 of the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Matter/Madder, Jacob: Private, Company K; initially reported as missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, his status was subsequently updated to “died of wounds” from that battle; his burial location remains unidentified;

Mayes, William (alternate spelling: Hayes, Mays): Private, Company D; fell ill during the opening days of the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to a Union Army general hospital; died there on March 30, 1864; was interred in grave no. 3945 of the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Miller, Jonathan: Private, Company A; cause and date of death have not yet been determined (soldier was identified by his military headstone); was interred in section 59, grave no. 4629 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Missmer, Benjamin (alternate spellings: Messner, Missimer, Missmer): Private, Company H; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the Union’s St. Louis General Hospital; died there on August 7, 1864; was interred in section 49, grave no. 3874 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery;

Orris, Nicholas: Private, Co. H; killed in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Osterstock, Jacob: Private, Company A; fell ill during the Red River Campaign; was transported to a Union Army hospital in Baton Rouge; died there on June 30, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Powell, Solomon: Private, Company D; may have been wounded in action; was captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; died from his battle wounds at Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, either on the same day as the battle, or on June 7, 1864, while being held by Confederate troops as a prisoner of war (POW); his burial location remains unidentified; per historian Lewis Schmidt, “Privates Powell and Wantz were probably buried in a cemetery at Pleasant Hill, ‘at the rear of the brick building used for a hospital,’ and after the war reinterred at Alexandria National Cemetery at Pineville, Louisiana in unknown graves”;

Resch, Charles (alternate spelling: Resk): Private, Company K; fell ill during the Red River Campaign; was transported to Baton Rouge and confined to a Union Army general hospital; died there on August 18, 1864; was interred in section 11, grave no. 629 at the Baton Rouge National Cemetery;

Ridgeway, John (alternate spelling: Ridgway): Private, Company H; fell ill during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans and confined to a Union Army general hospital; died there on July 30, 1864; was interred in section 57, grave no.4475 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Sanders, Francis (alternate spellings: Xander, Xandres): Corporal, Company B; wounded in action during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield, Louisiana on April 8, 1864; died shortly after being carried to the rear by his brother; his death was documented in the obituary of his widow, Henrietta Susan (Balliet) Sanders, in the May 15, 1916 edition of Allentown’s Morning Call newspaper, which reported that Francis Sanders “enlisted in the Forty-seventh regiment and saw service for two enlistments until the battle of Sabine Cross Roads, La., where he was wounded and carried to the rear by his brother. From that day to this not a word was heard from him and the supposition was that he died from his wounds” and was likely interred in an unknown, unmarked grave; his burial location remains unidentified;

Schaffer, Reuben Moyer (alternate spellings: Schaeffer, Scheaffer, Shaffer): Private, Company H; reported as wounded in action during either the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield on April 8, 1864 or the Battle of Pleasant Hill on April 9; was subsequently marched with his regiment to Grand Ecore; was reported in U.S. Army records to have died at Grand Ecore on April 22, 1864; however, he actually died during the forty-five-mile march toward Cloutierville, according to a letter subsequently written by his commanding officer, Captain James Kacy, to First Lieutenant William Wallace Geety on May 29; was likely interred in an unknown, unmarked grave; his burial location remains unidentified;

Schlu, Christian (alternate spellings: Schla, Schlea): Private, Company G; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the U.S. Marine Hospital; died there on June 2, 1864; was interred in section 58, grave no.: 4577 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Schweitzer, William (alternate spelling: Sweitzer): Corporal, Company A; fell ill during the Red River Campaign; was taken to the Union’s hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, which was docked near Morganza, Louisiana, and was hospitalized aboard that ship on June 20, 1864; diagnosed with typhoid fever, he died aboard ship four days later, on June 24, 1864 (alternate death date: June 23, 1864); his burial location remains unidentified;

Schwenk, Charles M.: Private, Company B; fell ill during the Red River Campaign; was transported to Baton Rouge, where he was confined to a Union general hospital; died there on June 20, 1864; was interred in section 8, grave no. 476 at the Baton Rouge National Cemetery;

Smith, Frederick: Private, Co. D; may have been wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was captured by Confederate troops during that battle and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until his death on May 4, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified, but may still be located on the grounds of the Camp Ford Historic Park;

Smith, George H.: Private, Company H; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was confined to the Union’s hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, and transported to Natchez, Mississippi, where he was hospitalized at the Union’s Natchez General Hospital; died there on July 9, 1864; was interred at the Natchez National Cemetery;

Smith, Henry: Private, Company G; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the U.S. Marine Hospital; died there on May 30, 1864; was interred in section 51, grave no. 4522 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Smith, Joseph: Private, Company B; fell ill during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the Union’s Barracks General Hospital; died there on September 2, 1864; was interred in section 60, grave no. 4768 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Snyder, Jonas: Private, Company I; fell ill and developed consumption during the Red River Campaign across Louisiana; died aboard the U.S. Steamer McClellan on July 8, 1864 while en route to Fortress Monroe, Virginia with his regiment; was buried at sea during a formal military burial ceremony, according to Company I First Lieutenant Levi Stuber’s affidavit that was filed on behalf of Jonas Snyder’s widow for her U.S. Civil War Widow’s Pension application;

Sterner, John C.: Private, Company C; killed in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was interred, or a cenotaph was erected on his behalf, at Lantz’s Emmanuel Cemetery in Sunbury, Pennsylvania;

Stick, Francis: Private, Company I; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the University General Hospital; died there on June 10, 1864; was interred in section 52, grave no. 4065 at the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Stocker, Josiah Simon: Private Company A; fell ill with dysentery during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the University General Hospital; died there on May 17, 1864; was interred in section 7, grave no. 368 at the Baton Rouge National Cemetery;

Straehley, Jeremiah (alternate spellings: Strackley, Strahle, Strahley): Private, Company G; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to a Union Army general hospital; died there on May 14, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Swoyer, Alfred P.: Second Lieutenant, Company K; was killed instantly after being struck by a minié ball in the right temple during the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads/Mansfield, Louisiana on April 8, 1884; his burial location remains unidentified;

Trabold, Jacob: Private, Company A; fell ill with dysentery during the Red River Campaign; died from disease-related complications at Morganza, Louisiana on June 27, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Wagner, Samuel: Private, Company D; was wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was lost at sea while being transported for medical care aboard the USS Pocahontas when that steam transport foundered off of Cape May, New Jersey, after colliding with the City of Bath on June 1, 1864; his body was never recovered;

Walbert, William S. (alternate spelling: Walberd): Private, Company K; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was hospitalized at the U.S. Marine Hospital; died there on April 30, 1864; his burial location remains unidentified;

Walters, James: Private, Unassigned Men; fell ill during the Red River Campaign; died on June 23, 1864 (per historian Lewis Schmidt); his death and burial locations remain unidentified;

Wantz, Jonathan: Private, Company D; may have been wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was captured by Confederate troops during that battle, and was then held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he died at Pleasant Hill—either the same day as that battle, or on June 17, 1864, while he was still being held as a POW by Confederate troops; his burial location remains unidentified (per historian Lewis Schmidt, “Privates Powell and Wantz were probably buried in a cemetery at Pleasant Hill, ‘at the rear of the brick building used for a hospital,’ and after the war reinterred at Alexandria National Cemetery at Pineville, Louisiana in unknown graves”);

Webster, John Eyres: Private, Company G; fell ill with fever during the Red River Campaign; was confined to a Union Army general hospital in Baton Rouge; died there from disease-related complications on June 24, 1864 (alternate death date: June 21, 1864); was interred in section 4, grave no. 190 at the Baton Rouge National Cemetery with a cenotaph erected for him by his family at the Old Saint David Church Cemetery in Wayne, Delaware County, Pennsylvania;

Weiss, John: Private, Co. F; was wounded in action and captured by Confederate troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was marched or transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until his death on July 15, 1864; his burial location remains unknown;

Williamson, Jacob: Private, Company A; fell ill with typhoid fever during the Red River Campaign; was transported to Baton Rouge, where he was confined to the Union’s Baton Rouge General Hospital; died there from malignant typhoid fever on July 13, 1864; was interred in section 9, grave no. 500 at the Baton Rouge National Cemetery;

Witz, John (alternate spellings: Wilts, Wiltz, Wilz, Witts): Private, Unassigned Men and Company E; fell ill with typhoid fever during the Red River Campaign, was taken to the Union’s hospital ship, the USS Laurel Hill, which was docked near Morganza, Louisiana; died aboard that ship on June 23, 1864 (alternate death date: June 21, 1864); was most likely buried at sea or near Morganza, Louisiana; however, his exact burial location remains unidentified;

Worley, John (alternate spellings: Wehle, Worly, Whorley): Private, Company F; fell ill with chronic diarrhea during the Red River Campaign; was transported to New Orleans, where he was confined to the Union’s St. Louis General Hospital; died there on July 15, 1864; was interred on July 16, 1864 in section 142, grave no. 3804 of the Monument Cemetery in New Orleans (now the Chalmette National Cemetery);

Wolf, Samuel (alternate first name: Simon): Private, Company K; was initially declared as missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was ultimately declared as having been killed in action during that battle after having been absent from muster rolls for a substantial period of time; his burial location remains unknown.

Sources:

- Civil War Muster Rolls (47th Pennsylvania Infantry, 1864). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File (47th Pennsylvania Infantry, 1864). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Gilbert, Randal B. A New Look at Camp Ford, Tyler Texas: The Largest Confederate Prison Camp West of the Mississippi River (3rd Edition). Tyler, Texas: The Smith County Historical Society, 2010.

- Prisoner of War Rosters, Camp Ford (47th Pennsylvania Infantry, 1864). Tyler, Texas: Smith County Historical Society, retrieved 2014.

- Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, 1861–1865 (NAID: 656639), in “Records of the Adjutant General’s Office” (Record Group 94). Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration.

- Registers of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-1865 (47th Regiment), in “Records of the Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs” (Record Group 19). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Roll of Honor: Names of Soldiers Who, in Defence [sic] of the American Union, Suffered Martyrdom in the Prison Pens throughout the South. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1867-1868.

- Scott, Col. Robert N., ed. The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Series I – Volume XXXIV – In Four Parts: Part II, Correspondence, etc.: Chapter XLVI: Louisiana and the Trans-Mississippi). Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1891.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Thoms, Alston V., principal investigator and editor, and David O. Brown, Patricia A. Clabaugh, J. Philip Dering, et. al., contributing authors. Uncovering Camp Ford: Archaeological Interpretations of a Confederate Prisoner-of-War Camp in East Texas. College Station, Maryland: Center for Ecological Archaeology, Department of Anthropology, Texas A & M University, 2000.

- Wharton, Henry. Letters from the Sunbury Guards, 1864. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American.

You must be logged in to post a comment.