This POW/MIA Recognition Flag designed by Newt Heisley was formally recognized by U.S. House of Representatives Resolution No. 467 on September 21, 1990 (public domain).

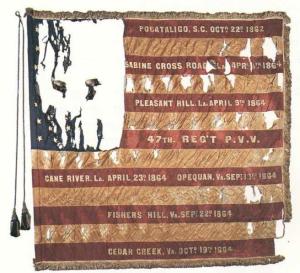

During the Army of the United States’ 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana in the American Civil War, multiple members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were declared as “Missing in Action” (MIA) — largely due to the confusion caused by a series of engagements with the enemy in which Union soldiers were repeatedly required to retreat, regroup and resume the fight as they faced down wave after wave of Confederate troops attempting to outflank and perform end runs around the outer edges of Union Army lines.

Each time the cannon smoke began to clear from those battles, many of those MIA members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry found their way back to the regiment, carrying word to senior officers of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers that members of the regiment had been captured by Confederate troops. By mid-May of 1864, it was clear that at least twenty-three 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were being held as prisoners of war (POWs) by the Confederate States Army.

Regimental leaders would later learn that many of those men had been force marched roughly one hundred and fifty miles to Camp Ford, which was located outside of Tyler, Texas and would become the largest Confederate POW camp west of the Mississippi River by the summer of 1864. Once there, they were starved, given minimal to no medical care for any wounds they had sustained, exposed to extreme variations in temperature and weather, due to inadequate shelter, and sickened by dysentery and other diseases that were spread by living in the cramped, overcrowded conditions that became increasingly unsanitary, due to the placement of latrine facilities near water supplies meant for drinking or bathing. As their days dragged on, their treatment by Confederate soldiers grew more and more harsh. According to representatives of the Smith County Historical Society who have been working on documenting the history of Camp Ford:

On April 8th and 9th 1864 at the battles of Mansfield and Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, Confederate forces captured more than 2,000 Union soldiers, who were quickly marched to Tyler…. The existing stockade did not have sufficient area to house them, and an emergency enlargement was undertaken. Local slaves were again impressed, the north and east wall was dug up and the logs cut in half, and the top ten feet of the logs of the south and west walls were cut off. The resulting half logs gave sufficient timber to quadruple the area of the stockade, and it was expanded to about eleven acres.

With additional battles in Arkansas and Louisiana, the prison population had grown to around 5,000 by mid-June. Hard-pressed CS officials had no ability to provide shelter for the new prisoners, and their suffering was intense. The number of tools was inadequate, and many men could only dig holes in the ground for shelter. Rations were often insufficient and the death rate soared…. Of 316 total deaths at the camp, 232 occurred between July and November 1864….

At least three 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers are confirmed to have died while imprisoned at Camp Ford. Another member of the regiment was later removed from that prison and moved to Andersonville, the most notorious of all American Civil War POW camps. Two others died as POWs who were confined to a Confederate hospital.

In recognition of National POW/MIA Recognition Day, which is observed on the third Friday each September in the United States of America, we pay tribute to those twenty-three brave souls.

DeSoto and Sabine Parishes (Mansfield and Pleasant Hill, Louisiana)

Possibly wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Privates Solomon Powell and Jonathan Wantz of Company D were captured during that battle on April 9, 1864. Private Powell died either that same day or on June 7, 1864, while still being held by Confederate troops as a POW at Pleasant Hill. Private Wantz also died while still being held as a POW at Pleasant Hill; his death was reported as having occurred on June 17, 1864. Their exact burial locations remain unidentified.

Confederate Hospital (Shreveport, Louisiana)

G Company Private Joseph Clewell — who had only been a member of the 47th Pennsylvania since mid-November 1863, fell ill sometime after being captured by Confederate troops during one of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Red River Campaign engagements in the spring of 1864. Suffering from chronic diarrhea due to the poor water quality and unsanitary living conditions that he endured while being held as a POW, he was subsequently confined to the Confederate States Army Hospital No. 59 in Shreveport, Louisiana sometime in May or early June. Held at that hospital as a POW, his health continued to decline until he died there on June 18, 1864, according to the U.S. Army’s Registers of Deaths of Volunteer Soldiers. His exact burial location also remains unidentified.

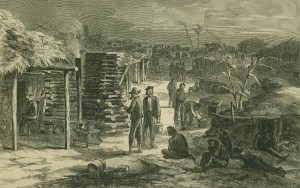

This illustration presented a rosier view of life at Camp Ford, the largest Confederate Army prison camp west of the Mississippi River, than was the actual situation for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers confined there (Harper’s Weekly, March 4, 1865, public domain).

Camp Ford or Camp Groce (Texas)

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers confirmed to have been released from Camp Ford or Camp Groce in Texas during a series of prisoner exchanges between the Army of the United States and the Confederate States Army were:

- Private Charles Frances Brown, Bugler of Company D and Regimental Band No. 2 (date of release: July 22, 1864; discharged after receiving medical treatment; re-enlisted with the 7th New York Volunteers in October 1864);

- Private Charles Buss/Bress of Company D (fell ill with dysentery while confined as a POW at Camp Ford and developed chronic diarrhea and severe hemorrhoids — conditions that would plague him for the remainder of his life, date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment and was honorably discharged from a Union Army medical facility in Philadelphia in May 1865);

- Private Ephraim Clouser of Company D (captured after being shot in the right knee, date of release: November 25, 1864; placed on Union Army sick rolls after being diagnosed as being too traumatized to remain on duty, he was transferred to the Union Army’s Jefferson Barracks Hospital in St. Louis, Missouri, then to a Union Army hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio and then to the Union Army’s general hospital in York, Pennsylvania, where he remained until the end of the war; still suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) after the war, he was declared by the Pennsylvania court system to be unable to care for himself, and was confined to the Harrisburg State Hospital for the remainder of his life);

- Sergeant James Crownover of Company D (captured after being shot in the right shoulder, date of release: November 25, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty);

- Private James Downs of Company D (date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment and returned to duty; possibly suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), he fell from a window of the Brookville Memorial Home in Jefferson County, Pennsylvania in 1921);

- Private Conrad P. Holman, of Company C (date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty);

- Corporal James Huff of Company E (captured after being wounded, date of release: August 29, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty; captured by Confederate troops during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1864, was transported and force marched to North Carolina, where he was held as a POW at the Salisbury Prison Camp until his death there from starvation and harsh treatment on March 5, 1865; he was subsequently buried somewhere on the POW camp grounds in an unmarked mass trench grave of Union soldiers);

- Private John Lewis Jones of Company F (captured after being wounded, date of release: September 24, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty);

- Private Edward Mathews of Company C (date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty);

- Private Adam Maul/Moll/Moul of Company C (captured on May 3, 1864, while away from his regiment’s encampment in Alexandria, Louisiana — possibly while assigned to duties related to the construction of Bailey’s Dam, date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and was assigned to detached duty at Hilton Head, South Carolina on January 3, 1865, but was reportedly not given discharge paperwork by his regiment; his exact burial location remains unidentified);

- Private John W. McNew of Company C (captured after being wounded, date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty);

- Corporal John Garber Miller of Company D (date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty);

- Private Samuel W. Miller of Company C (date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty);

- Private John Wesley Smith of Company C (date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty;

- Private William J. Smith of Company D (date of release: July 22, 1864; received medical treatment, recovered and returned to duty; and

- Private Benjamin F. Wieand/Weiand of Companies B and D (captured after being wounded; received medical treatment after his release from captivity and was honorably discharged on July 21, 1865.

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers confirmed to have died on the grounds of Camp Ford were:

- Private Samuel M. Kern of Company D (date of death: June 12, 1864);

- Private Frederick Smith of Company I (date of death: May 4, 1864); and

- Private John Weiss, Company F (captured after being severely wounded, he was initially confined to Camp Ford, but was then transferred to a “Rebel hospital” for treatment of his wounds, according to regimental records; died at that Confederate hospital on July 15, 1864).

The burial locations of Privates Samuel Kern, Frederick Smith and John Weiss remain unidentified. (The Confederate hospital where Private John Weiss died may have been the Confederate Army Hospital No. 59 in Shreveport, Louisiana — the same Confederate hospital where G Company Private Joseph Clewell died on June 18, 1864.)

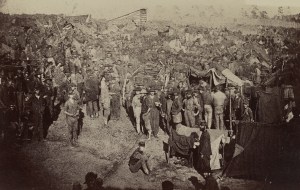

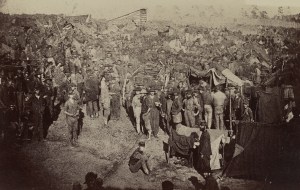

Issuing Rations at the Andersonville POW Camp, August 17, 1864 (view from Main Gate, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Andersonville (Fort Sumter, Georgia)

According to an article in the April 12, 1911 edition of the Reading Eagle, Private Ben Zellner of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Company K had also begun his imprisonment as a POW at Camp Ford, but was later transported to Georgia, where he was confined to Andersonville, the most notorious Confederate prison camp of them all.

Benjamin Zellner, who was one of the youngest soldiers during the Civil War, was captured by the Confederates at Pleasant Hill, La., April 8, 1864. He was a member of Co. K, 47th Regiment, with Gen. Banks’ army on the Red River expedition. Comrade Zellner was wounded in a charge to the left of the lines and fell on the field. The Union forces being driven back, he, with a number of others was captured. After being kept at Pleasant Hill two weeks, they were removed to Mansfield, La., on a Saturday night and kept over night [sic] in the Court House until Sunday morning. Thence they were removed to Shreveport, La., and again kept in the Court House. From thence they were marched 110 miles to Unionville prison at Tyler, Tex…. The 47th was the only Penn’a Regiment to participate in the Red River campaign.

Although POW records from Camp Ford that are maintained by the Smith County Historical Society note that a “Ben Cellner” was released in that camp’s July 22, 1864 prisoner exchange with the Union Army, interviews by several different newspaper reporters of Zellner in his later life contradict those records. According to Zellner and the Reading Eagle, he had been transported to Camp Sumter near Anderson, Georgia sometime in May or June 1864:

In about a month [after arriving at Camp Ford in Texas, following their 8 April capture in Louisiana] 300 or 400 of the strongest were brought back to Shreveport and then transported down the Red River to an old station and marched four days, when they were taken by train to Andersonville….

At the time of Private Zellner’s internment, Andersonville was under the command of Henry Wirz, who would later be convicted of war crimes for his brutal treatment of Union prisoners. According to the September 21, 1864 edition of The Soldiers’ Journal:

Those Union prisoners recently released from Camp Sumter, at Andersonville, Ga., have made affidavit of the condition of the 35,000 prisoners confined there. The horrors of their imprisonment, plainly and unaffectedly narrated, have no parallel outside of Taeping or Malay annals. Twenty-five acres of human beings – so closely packed that locomotion is made obsolete, compelled to drink from sewers, and to eat raw meat like cannibals – are dwelling under vigilant espionage, hopeless, helpless, and Godless. Some are lunatic, and others have become desperately wicked; all are living, loathing, naked, starved fellow-men.

Reportedly held as a POW for six months and fourteen days, according to the March 26, 1915 edition of The Allentown Leader, Zellner was freed from captivity during a Union and Confederate army prisoner exchange in September 1864 (per a report in the April 12, 1911 edition of the Reading Eagle). The April 8, 1911 Allentown Leader noted that, after this prisoner exchange, which took place “along the James River,” he was then sent with a number of his fellow former POWs “to Washington, to Fortress Monroe, to New York and home.” Following a period of recovery, he then returned to service with his regiment just in time to participate in a key portion of Union Major-General Phillip Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign.

Read their stories. Remember their names. Honor their individual sacrifices.

Sources:

- “47 Years Today Since Rebels Caught Him: This Is a Memorable Anniversary for Comrade Ben Zellner.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, April 8, 1911.

- Allentown’s Youngest Civil War Veteran (profile of Private Ben Zellner). Reading, Pennsylvania: Reading Eagle, April 12, 1911.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Camp Ford,” in “Texas Beyond History.” Austin, Texas: Texas Archaeological Research Laboratory, University of Texas at Austin, retrieved online January 24, 2025.

- Camp Ford Prison Records (47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, 1864). Tyler, Texas: Smith County Historical Society.

- “Camp Sumter,” in “Editorial Jottings.” Washington, D.C.: The Soldiers’ Journal, September 21, 1864.

- Civil War Muster Rolls (47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Gilbert, Randal B. A New Look at Camp Ford, Tyler, Texas: The Largest Confederate Prison Camp West of the Mississippi River, 3rd Edition. Tyler, Texas: The Smith County Historical Society, 2010.

- “His Glorious Record as a Soldier: Fought at Gettysburg, Red River and Shenandoah Valley and Besides Enduring the Horrors of Andersonville, Carries Bullet to This Day.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, March 26, 1917.

- Horwitz, Tony. “Did Civil War Soldiers Have PTSD?“, in Smithsonian Magazine, January 2015. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution.

- Lawrence, F. Lee. “Camp Ford,” in “Hand Book of Texas.” Austin, Texas: Texas State Historical Association, retrieved online January 24, 2025.

- “Newport: Special Correspondence” (notice documenting Ephraim Clouser’s confinement for mental illness and later death at the asylum in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Daily Independent, March 18, 1899.

- “POW/MIA Recognition Day.” Indianapolis, Indiana: The American Legion National Headquarters, retrieved online September 19, 2025.

- Registers of Deaths of Volunteers. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, 1864-1865.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Simmons, G. W. “Camp Ford, Texas” (sketch, Harper’s Weekly, March 4, 1865; retrieved June 9, 2015, via University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History, crediting Star of the Republic Museum, Washington, Texas).

- Slattery, Joe. “Confederate Soldiers Who Died at the Confederate General Hospital in Shreveport, Louisiana,” in The Genie, vol. 37, no. 1 (First Quarter, 2003), p. 12. Shreveport, Louisiana: Ark-La-Tex Genealogical Association.

- “The Exchange of Prisoners; The Cartel Agreed Upon by Gen. Dix for the United States, and Gen. Hill for the Rebels,” in “Supplementary Articles.” New York, New York: The New York Times, October 6, 1862.

- Thoms, Alston V., principal investigator and editor, and David O. Brown, Patricia A. Clabaugh, J. Philip Dering, et. al., contributing authors. Uncovering Camp Ford: Archaeological Interpretations of a Confederate Prisoner-of-War Camp in East Texas. College Station, Texas: Center for Ecological Archaelogy, Department of Anthropology, Texas A & M University.

- “Union Army Deaths in Shreveport 1864-1865.” Shreveport, Louisiana: Sons of Union Veterans, Brig. Gen. Joseph Bailey Camp No. 5, retrieved April 29, 2021.

- “Up in Perry” (notice of Ephraim Clouser’s arrest and sanity hearing). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Telegraph, September 22, 1892.

- Wharton, Henry D. Letters from the Sunbury Guards, 1861-1866. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American.

You must be logged in to post a comment.