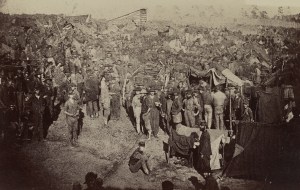

Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana, April 9, 1864 (Harper’s Weekly, May 7, 1864, public domain).

Arriving at Pleasant Hill, Louisiana around 8:30 a.m. on April 9, 1864, after having retreated from the scene of the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads just before midnight on April 8, and with the enemy believed to be in pursuit, Union Major-General Nathaniel Banks ordered his troops (including the (47th Pennsylvania Volunteers) to regroup and ready themselves for a new round of fighting. That fight would later be known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill.

In his official Red River Campaign Report penned a year later, Banks described how the day unfolded:

A line of battle was formed in the following order: First Brigade, Nineteenth Corps, on the right, resting on a ravine; Second Brigade in the center, and Third Brigade on the left. The center was strengthened by a brigade of General Smith’s forces, whose main force was held in reserve. The enemy moved toward our right flank. The Second Brigade [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] withdrew from the center to the support of the First Brigade. The brigade in support of the center moved up into position, and another of General Smith’s brigades was posted to the extreme left position on the hill, in echelon to the rear of the left main line.

Light skirmishing occurred during the afternoon. Between 4 and 5 o’clock it increased in vigor, and about 5 p.m., when it appeared to have nearly ceased, the enemy drove in our skirmishers and attacked in force, his first onset being against the left. He advanced in two oblique lines, extending well over toward the right of the Third Brigade, Nineteenth Corps. After a determined resistance this part of the line gave way and went slowly back to the reserves. The First and Second Brigades were soon enveloped in front, right, and rear. By skillful movements of General Emory the flanks of the two brigades, now bearing the brunt of the battle, were covered. The enemy pursued the brigades, passing the left and center, until he approached the reserves under General Smith, when he was met by a charge led by General Mower and checked. The whole of the reserves were now ordered up, and in turn we drove the enemy, continuing the pursuit until night compelled us to halt.

First State Color, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (issued September 20, 1861, retired May 11, 1865).

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had been ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines that day (April 9, 1864), their right flank spreading up onto a high bluff. According to Bates, after fighting off a charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor, the 47th was forced to bolster the buckling lines of the 165th New York Infantry—just as the 47th was shifting to the left of the massed Union forces.

Nearly two decades later, First Lieutenant James Hahn recalled his involvement (as a sergeant in that battle) for a retrospective article in the January 31, 1884 edition of The National Tribune:

A PENNSYLVANIA SOLDIER’S EXPERIENCE.

Lieutenant James Hahn, of the 47th Pennsylvania infantry, writing from Newport, Pa., refers as follows to the engagements at Sabine Cross-roads and Pleasant Hill:

‘The 19th Corps had gone into camp for the evening about four miles from Sabine Cross-Roads. The engagement at Mansfield had been fought by the 13th Corps, who struggled bravely against overwhelming odds until they were driven from the field. I presume the rebel Gen. Dick Taylor knew of the situation of our army, and that the 19th was in the rear of the 13th, and the 16th still in rear of the 19th, some thirteen miles away, encamped at Pleasant Hill. They thought it would be a good joke to whip Banks’ army in detail: first, the 13th corps, then 19th, then finish up on the 16th. But they counted without their hosts; for when the couriers came flying back to the 19th with the news of the sad disaster that had befallen the 13th corps, we were double-quicked a distance of some four miles, and just met the advance of our defeated 13th corps – coming pell-mell, infantry, cavalry, and artillery all in one conglomerated mass, in such a manner as only a defeated and routed army can be mixed up – at Sabine Cross-roads, where our corps was thrown into line just in time to receive the victorious and elated Johnnies with a very warm reception, which gave them a recoil, and which stopped their impetuous headway, and gave the 13th corps time to get safely to the rear. I do not know what would have been the consequence if the 19th had been defeated also, that evening of the 8th, at Sabine Cross-roads, and the victorious rebel army had thrown themselves upon the ‘guerrillas’ then lying in camp at Pleasant Hill. It was just about getting dark when the Johnnies made their last assault upon the lines of the 19th. We held the field until about midnight, and then fell back and left the picket to hold the line while we joined the 16th at Pleasant Hill the morning of the 9th of April, soon after daybreak. It was not long until the rebel cavalry put in an appearance, and soon skirmishing commenced. About 4 o’clock in the afternoon the engagement become general all along the line, and with varied success, until late in the afternoon the rebels were driven from the field, and were followed until darkness set in, and about midnight our army made a retrograde movement, which ended at Grand Ecore, and left our dead and wounded lying on the field, all of whom fell into rebel hands. I have been informed since by one of our regiment, who was left wounded on the field, that the rebels were so completely defeated that they did not return to the battlefield till late the next day, and I have always been of the opinion that, if the defeat that the rebels got at Pleasant Hill had been followed up, Banks’ army, with the aid of A. J. Smith’s divisions, could have got to Shreveport (the objective point) without much left or hindrance from the rebel army.’

According to Major-General Banks, “The battle of the 9th was desperate and sanguinary. The defeat of the enemy was complete, and his loss in officers and men more than double that sustained by our forces.”

Even so, casualties for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry that day were high. The abridged lists below partially documents the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who were declared as wounded in action, killed in action, missing in action, or captives of the Confederate States Army (POWs) after the Battle of Pleasant Hill:

Killed or Wounded in Action:

Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, circa 1861 (public domain).

Alexander, George Warren: Lieutenant-Colonel and second in command of the regiment; struck in the left leg near the ankle by a shell fragment which fractured his leg; recovered and returned to duty; was honorably discharged upon expiration of his three-year term of service on September 23, 1864.

Baldwin, Isaac: Corporal, Company D; twice wounded in action in 1864, he was first wounded during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company D; wounded in action the second time during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company D; subsequently promoted to the rank of sergeant on January 20, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Buss, Charles (alternate spelling: Bress): Private, Company F; initially declared missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, Union Army leaders ultimately determined that he had been captured by Confederate States Army troops during that battle; marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas; held captive there as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: This was likely the “Charles Bress” shown on Camp Ford prisoner records as a private from Company D.) After recovering from his POW experience, he remained on the Company F rosters until he was honorably discharged in January 1865.

Clouser, Ephraim: Private, Company D; shot in the right knee and then captured by Confederate Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on November 25, 1864; placed on the sick rolls of the Army of the United States after his release from captivity, he was hospitalized at the Union Army’s Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri before being transferred to a Union Army hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio for more advanced care for his battle wound — and possibly also for “Soldiers’ Heart”/post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); from there, he was sent home to Pennsylvania to convalesce at the Union Army’s general hospital in York, Pennsylvania; honorably discharged after that convalescence, his exact muster out date remains unclear; described, post-war, as “an insane veteran,” he was repeatedly institutionalized throughout his remaining years.

Crownover, James: Sergeant, Company D; survived slight breast wound during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862; sustained gunshot wound to the right shoulder and was captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported to Camp Groce or Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held until he was released during a prisoner exchange on November 25, 1864; while he was being held as a POW, he was commissioned, but not mustered as a second lieutenant on August 31, 1864; recovered following medical treatment; returned to duty with Company C and was promoted to the rank of first sergeant on July 5, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Dingler, John: Private, Company E; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company E; was honorably discharged upon expiration of his three-year term of enlistment on September 18, 1864; later re-enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania’s B Company on February 13, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Dumm, William F. (alternate spellings: Drum or Drumm): Private, Company H; killed in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864.

Fink, Edward: Private, Company B; killed in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864.

Frack, William: Corporal, Company I; declared missing in action and “supposed dead” following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was ultimately declared as killed in action.

Hagelgans, Nicholas: Private, Company K; killed in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864.

Hahn, Richard: Private, Company E; killed in action by a musket ball during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864.

Haltiman, William (alternate spellings: Haldeman or Halderman): Second Lieutenant, Company I; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company I; promoted to the rank of sergeant on January 1, 1865; promoted to the rank of second lieutenant on May 27, 1865; felled by sunstroke while on duty in mid-July 1865, he died in Pineville, South Carolina on July 21, 1865.

Hangen, Granville D.: Private, Company I; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company I; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Hartshorn, John (alternate spelling: Hartshorne): Private, Company H; initially listed as missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, Union Army officials ultimately determined that he had been captured by Confederate States Army troops and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: His surname was spelled as “Hartshorne” in Camp Ford’s prisoner records, which also described him as “illiterate” and incorrectly listed his company as “K.”) He subsequently died at a Union Army hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana on August 8, 1864.

Huff, James: Corporal, Company E; wounded in action and captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on August 29, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company E; was captured again by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1864; was marched or was transported to the Salisbury Prison Camp in Salisbury, North Carolina, where he was again held captive as a POW—this time, until his death on March 5, 1865. Per historian Lewis Schmidt, it was “reported [by a fellow soldier that] ‘he got his throat cut with a ball and I sott him up against stump to die.’” He was subsequently buried by Confederate States Army soldiers in one of the unmarked trench graves at the Salisbury Prison Camp.

Jones, John L.: Private, Company F; wounded in action and captured by Confederate troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas; promoted by his regiment on September 18, 1864 while he was still being held as a POW at Camp Ford, he was finally released during a prisoner exchange on September 24, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company F, he was promoted to the rank of sergeant on June 2, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Kennedy, James: Private, Company C; sustained gunshot fracture of the arm and gunshot wound to his side during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was transported to the Union Army’s St. James Hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana, where he died from his battle wounds on April 27, 1864.

Kern, Samuel M.: Private, Company D; wounded in action and captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held in captivity as a prisoner of war (POW) until he died on June 12, 1864.

Kramer, Cornelius: Private, Company C; wounded in the leg during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company C; was honorably discharged on December 16, 1865.

Matter, Jacob (alternate spelling: Madder): Private, Company K; initially reported as missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, his status was subsequently updated to “died of wounds” from that battle.

Mayers, William H. (alternate spellings: Mayer, Mayers, Meyers, Moyers; shown on regimental muster rolls as “Mayers, William H.” and “Meyers, William H.”; listed in Samuel P. Bates’ History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5 and various other records as “Moyers I, William H.”): Corporal, Co. I; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company I; promoted to the rank of sergeant on September 19, 1864; was subsequently wounded in action again—this time during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1864; recovered and returned to duty; promoted to the rank of first sergeant on May 27, 1865; was commissioned, but not mustered as a second lieutenant on July 25, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

McNew, John: Private, Company C; wounded in action and captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1964; marched to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas and held captive there as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: Camp Ford records incorrectly listed him as a member of Company D and also described him as “illiterate.”) Promoted to the rank of corporal on December 1, 1864; reduced to the rank of private on April 22, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Miller, George: Private, Company C; wounded in the side during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was honorably mustered out upon expiration of his three-year term of service on September 18, 1864; died suddenly in his hometown in 1867.

Miller, John Garber: Corporal, Company D; wounded in action and captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, he was marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: Camp Ford records incorrectly listed him as a member of Co. G.) Recovered and returned to duty with Company D, he was subsequently promoted to the rank of sergeant on September 19, 1864; was honorably mustered out on December 25, 1865.

Moser, Peter (alternate spelling: “Moses”): Private, Company F; survived arm wound sustained during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862; was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability on February 24, 1863; recovered and re-enlisted with Company F on December 19, 1863; initially declared missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864. Union Army officers subsequently determined that he had been captured in battle at Pleasant Hill and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: His surname was listed on Camp Ford prisoner records as “Moses,” which also described him as “illiterate.”) Transported to New Orleans for treatment at a Union Army hospital, he remained “Absent and sick at New Orleans since 22 July 1864,” according to his Civil War Veterans’ Card File entry in the Pennsylvania State Archives, which also noted that he was “Supposed to be Dis. Under G.O. #77 A.G.O. W.D. Series 1865.” He ultimately survived the war and died in Pennsylvania in 1905.

O’Brien, William H.: Private, Company H; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company H; was honorably discharged on December 6, 1864.

Offhouse, William: Private, Company F; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company F; was honorably discharged upon expiration of his three-year term of service on September 18, 1864.

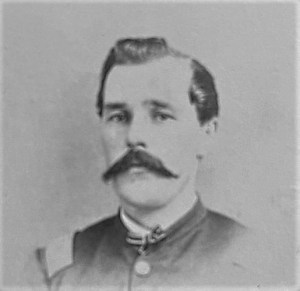

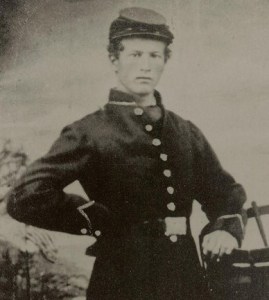

Private Nicholas Orris, Company H, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, circa 1863 (public domain).

Orris, Nicholas: Private, Co. H; killed in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; burial location remains unknown.

Petre, Pete: Private, Company D; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company D; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Powell, Solomon: Private, Company D; possibly wounded in action, he was captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; he then died from his battle wounds at Pleasant Hill, Louisiana either that same day or on June 7, 1864 while still being held by Confederate troops as a prisoner of war (POW). According to historian Lewis Schmidt, “Privates Powell and Wantz were probably buried in a cemetery at Pleasant Hill, ‘at the rear of the brick building used for a hospital,’ and after the war reinterred at Alexandria National Cemetery at Pineville, Louisiana in unknown graves.”)

Pyers, William: Sergeant, Company C; wounded in the arm and side while saving the flag from fallen C Company Color-Bearer Benjamin Walls; recovered and returned to duty with Company C; killed in action during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1864.

Reinert, Griffin (alternate spelling: Reinhart, Griffith; known as “Griff”): Private, Company F; sustained a gunshot wound to his jaw during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; was transported to the Union Army Hospital in York, Pennsylvania for more advanced medical care; was discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability on December 28, 1864.

Reinsmith, Tilghman: Private and Field Musician—Bugler, Company B; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company B; promoted to the rank of corporal on October 1, 1864; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Scheetz, Robert (alternate spelling Sheats): Private, Company F; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company F; was honorably discharged upon expiration of his three-year term of service on September 18, 1864.

Schleppy, Llewellyn J. (alternate spelling “Sleppy”): Private, Company F; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company F; was honorably discharged upon expiration of his three-year term of service on September 18, 1864.

Shaver, Joseph Benson: Private, Company D; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company D; was honorably discharged at Washington, D.C. on June 1, 1865.

Smith, Frederick: Private, Co. D; possibly wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; captured by Confederate States Army troops during that battle and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until his death on May 4, 1864.

Sterner, John C.: Private, Company C; killed in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864.

Stewart, Cornelius Baskins: Corporal, Company D; after surviving a wound sustained during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862, he recovered, was released to the regiment on December 15, 1862, and returned to active duty on March 1, 1863; shot in the right hip during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, he recovered and returned to duty again with Company D; he was honorably discharged upon completion of his three-year term of service on September 18, 1864.

Wagner, Samuel: Private, Company D; wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, he was lost at sea while being transported for medical care aboard the USS Pocahontas when that steam transport foundered off of Cape May, New Jersey after colliding with the City of Bath on June 1, 1864.

Walls, Benjamin: Regimental Color-Sergeant, Company C; sustained gunshot wound to his left shoulder while trying to mount the 47th Pennsylvania’s flag on a piece of Confederate artillery that had been re-captured by the regiment; recovered and attempted to re-enlist, but was denied permission due to his age. (At sixty-seven, he was the oldest man to serve in the entire regiment.) Was honorably discharged upon expiration of his three-year term of service on September 18, 1864.

Wantz, Jonathan: Private, Company D; possibly wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; captured by Confederate States Army troops during that battle, he was then held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he died at Pleasant Hill—either the same day or on June 17, 1864 while he was still being held as a POW by Confederate troops. According to historian Lewis Schmidt, “Privates Powell and Wantz were probably buried in a cemetery at Pleasant Hill, ‘at the rear of the brick building used for a hospital,’ and after the war reinterred at Alexandria National Cemetery at Pineville, Louisiana in unknown graves.”)

Weiss, John: Private, Co. F; Wounded in action and captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until his death on July 15, 1864; his burial location remains unknown.

Wieand, Benjamin: Private, Company D; Survived wound to his right thigh during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862; recovered and transferred to Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers on December 15, 1863; wounded in action and captured by Confederate States Army troops during Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, he was marched or was transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange (possibly after July 1864); was honorably discharged on July 21, 1865.

Wolf, Samuel: Private, Company K; initially declared as missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, he was ultimately declared as having been killed in action during that battle after having been absent from muster rolls for a substantial period of time.

Zellner, Benjamin (alternate spelling: Cellner): Private, Company K; wounded in action four times in 1864; was shot in the leg and lost an eye during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; captured during that same battle by Confederate States Army troops, he was confined initially at Pleasant Hill and Mansfield before being marched or transported to Camp Ford near Tyler Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW). Note: Although Camp Ford records (under surname of “Cellner”) stated in 2010 that he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864, Zellner stated in multiple newspaper accounts after war’s end that he was one of a group of three to four hundred men who had been deemed well enough by Camp Ford officials to be shipped to Shreveport, Louisiana, where they were then processed and sent by rail to Andersonville, the notorious Confederate POW camp in Georgia. Finally released from Andersonville in September 1864, he recovered and returned to duty with Company K. He was then wounded in the leg and also suffered a bayonet wound during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1964; recovered from those wounds and returned to duty with Company K; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865. During a newspaper interview in later life, he told the reporter that his bayonet wound had never healed properly.

Captured and Held as Prisoners of War (POWs):

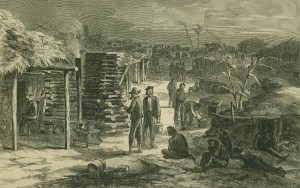

This image depicts life at Camp Ford, the largest Confederate Army prison camp west of the Mississippi River (Harper’s Weekly, March 4, 1865, public domain).

Brown, Francis or Charles: Private and Musician/Bugler, Company D and Regimental Band No. 2; captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864 and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864; subsequently awarded a furlough to recuperate, he was mistakenly listed on regimental rosters as having deserted while on leave on September 16, 1864 when, in fact, he had actually re-enlisted as a bugler with the 7th New York Volunteers in October 1864, signaling that there had either been a miscommunication with him about the furlough (his native language was German), or that he had developed a mental impairment during his captivity as a POW; he went on to serve with the 7th New York until he was honorably mustered out at Hart Island, New York on August 4, 1865

Buss, Charles (alternate spelling: Bress): Private, Company F; initially declared missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, Union Army leaders ultimately determined that he had been captured by Confederate States Army troops during that battle; marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, he was held captive there as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: This was likely the “Charles Bress” shown on Camp Ford prisoner records as a Private from Company D.) After recovering from his POW experience, he remained on the Company F rosters until he was honorably discharged in January 1865.

Clouser, Ephraim: Private, Company D; shot in the right knee and then captured by Confederate Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on November 25, 1864; placed on the sick rolls of the Army of the United States after his release from captivity, he was hospitalized at the Union Army’s Jefferson Barracks in St. Louis, Missouri before being transferred to a Union Army hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio for more advanced care for his battle wound — and possibly also for “Soldiers’ Heart”/post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD); from there, he was sent home to Pennsylvania to convalesce at the Union Army’s general hospital in York, Pennsylvania; honorably discharged after that convalescence, his exact muster out date remains unclear; described, post-war, as “an insane veteran,” he was repeatedly institutionalized throughout his remaining years.

Crownover, James: Sergeant, Company D; survived slight breast wound during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862; sustained gunshot wound to the right shoulder and was captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported to Camp Groce or Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive until he was released during a prisoner exchange on November 25, 1864; while he was being held as a POW, he was commissioned, but not mustered as a second lieutenant on August 31, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company C; promoted to the rank of first sergeant on July 5, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

James Downs (circa 1880s, public domain).

Downs, James: Private, Company D; captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864 and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company D; promoted to the rank of corporal on July 5, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Fisher, Charles B.: Private, Company K; captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: Camp Ford’s prisoner records described him as “illiterate.”) Recovered and returned to duty with Company K; was honorably discharged upon expiration of his three-year term of service on September 18, 1864.

Hartshorn, John (alternate spelling: Hartshorne): Private, Company H; initially listed as missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, Union Army officials ultimately determined that he had been captured by Confederate States Army troops and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: His surname was spelled as “Hartshorne” in Camp Ford’s prisoner records, which also described him as “illiterate” and incorrectly listed his company as “K.”) He subsequently died at a Union Army hospital in New Orleans, Louisiana on August 8, 1864.

Huff, James: Corporal, Company E; wounded in action and captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on August 29, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company E; was captured again by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1864; was marched or transported to the Salisbury Prison Camp in Salisbury, North Carolina, where he was again held captive as a POW—this time, until his death on March 5, 1865. Per historian Lewis Schmidt, it was “reported [by a fellow soldier that] ‘he got his throat cut with a ball and I sott him up against stump to die.’” was buried by Confederate States Army soldiers in one of the unmarked trench graves at the Salisbury Prison Camp.

Jones, John L.: Private, Company F; wounded in action and captured by Confederate troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW); promoted by his regiment on September 18, 1864 while he was still being held as a POW at Camp Ford, he was finally released during a prisoner exchange on September 24, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company F, he was promoted to the rank of sergeant on June 2, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Kern, Samuel M.: Private, Company D; wounded in action and captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he died on June 12, 1864.

McNew, John: Private, Company C; wounded in action and captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1964; marched to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas and held captive there as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: Camp Ford records incorrectly listed him as a member of Company D and also described him as “illiterate.) Promoted to the rank of corporal on December 1, 1864; reduced to the rank of private on April 22, 1865; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Miller, John Garber: Corporal, Company D; wounded in action and captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: Camp Ford records incorrectly listed him as a member of Co. G.) Recovered and returned to duty with Company D, he was subsequently promoted to the rank of sergeant on September 19, 1864; was honorably mustered out on December 25, 1865.

Moser, Peter (alternate spelling: “Moses”): Private, Company F; survived arm wound sustained during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862; was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability on February 24, 1863; recovered and re-enlisted with Company F on December 19, 1863; initially declared missing in action following the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, Union Army officers subsequently determined that he had been captured in battle at Pleasant Hill and marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864. (Note: His surname was listed on Camp Ford prisoner records as “Moses,” which also described him as “illiterate.”) Transported to New Orleans for treatment at a Union Army hospital, he remained “Absent and sick at New Orleans since 22 July 1864,” according to his Civil War Veterans’ Card File entry in the Pennsylvania State Archives, which also noted that he was “Supposed to be Dis. Under G.O. #77 A.G.O. W.D. Series 1865.” He ultimately survived the war and died in Pennsylvania in 1905.

Powell, Solomon: Private, Company D; possibly wounded in action, he was also captured during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; he then died from his battle wounds at Pleasant Hill, Louisiana either that same day or on June 7, 1864 while still being held by Confederate troops as a POW. According to historian Lewis Schmidt, “Privates Powell and Wantz were probably buried in a cemetery at Pleasant Hill, ‘at the rear of the brick building used for a hospital,’ and after the war reinterred at Alexandria National Cemetery at Pineville, Louisiana in unknown graves.”)

Smith, Frederick: Private, Company D; possibly wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; captured during that battle by Confederate States Army troops, he was marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until his death on May 4, 1864.

Smith, John Wesley: Private, Company C; captured by Confederates during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864; recovered and returned to duty with Company C; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865.

Smith, William J.: Private, Company D; captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1874. (Note: Camp Ford’s prisoner records described him as “illiterate.”) Honorably mustered out on December 25, 1865, he suffered from scurvy, which was likely attributable to his POW experience. Injured in a work-related accident in May 1891, he contracted tetanus due to that injury and died from lock-jaw in Duncannon, Pennsylvania on 3 June 1891.

Wantz, Jonathan: Private, Company D; possibly wounded in action during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1863, he was then captured by Confederate States Army troops and held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he died at Pleasant Hill—either the same day or on June 17, 1864 while he was still being held as a POW by Confederate troops. According to historian Lewis Schmidt, “Privates Powell and Wantz were probably buried in a cemetery at Pleasant Hill, ‘at the rear of the brick building used for a hospital,’ and after the war reinterred at Alexandria National Cemetery at Pineville, Louisiana in unknown graves.”)

Weiss, John: Private, Co. F; Wounded in action and captured by Confederate States Army troops during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; marched or was transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until his death on July 15, 1864; his burial location remains unknown.

Wieand, Benjamin: Private, Company D; Survived wound to his right thigh during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on October 22, 1862; recovered and transferred to Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers on December 15, 1863; wounded in action and captured by Confederate States Army troops during Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864, he was marched or was transported to Camp Ford near Tyler, Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW) until he was released during a prisoner exchange (possibly after July 1864); was honorably discharged on July 21, 1865.

Zellner, Benjamin (alternate spelling: Cellner): Private, Company K; wounded in action four times in 1864; was shot in the leg and lost an eye during the Battle of Pleasant Hill, Louisiana on April 9, 1864; captured during that same battle by Confederate States Army troops, he was confined initially at Pleasant Hill and Mansfield before being marched or transported to Camp Ford near Tyler Texas, where he was held captive as a prisoner of war (POW). Note: Although Camp Ford records (under surname of “Cellner”) stated in 2010 that he was released during a prisoner exchange on July 22, 1864, Zellner stated in multiple newspaper accounts after war’s end that he was one of a group of three to four hundred men who had been deemed well enough by Camp Ford officials to be shipped to Shreveport, Louisiana, where they were then processed and sent by rail to Andersonville, the notorious Confederate POW camp in Georgia. Finally released from Andersonville in September 1864, he recovered and returned to duty with Company K. He was then wounded in the leg and also suffered a bayonet wound during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1964; recovered from those wounds and returned to duty with Company K; was honorably discharged on December 25, 1865. During a newspaper interview in later life, he told the reporter that his bayonet wound had never healed properly.

Sources:

- “A Pennsylvania Soldier’s Experience.” Washington, D.C.: The National Tribune, January 31, 1884.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Prisoner of War Records, Camp Ford and Camp Groce (47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry). Tyler Texas: Smith County Historical Society, 2010.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

You must be logged in to post a comment.