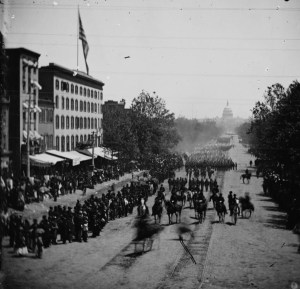

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff following the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Headquartered at Camp Brightwood in the Brightwood district of Washington, D.C.’s northwestern section since late April 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were attached to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps. Their job was to prevent former Confederate States military troops and their sympathizers from reigniting the flames of civil war in the wake of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination.

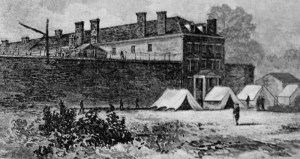

Multiple members of the regiment had only recently completed their detached duties as guards at the military prison where the key conspirators in their commander-in-chief’s murder were being held during their historic trial, and the regiment as a whole had just marched in the Union’s Grand Review of the National Armies on May 23.

Unidentified Union infantry regiment, Camp Brightwood, Washington, D.C., circa 1865 (public domain).

Now, as the majority of Union Army soldiers were being granted honorable discharges from the military, the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were hurriedly packing their belongings — but for transport to south, rather than back home. Meanwhile, as that frenzy of activity was unfolding, a “lucky few” of their comrades were being transferred to other federal military units, while others were receiving word that they would be honorably discharged via general orders that had been issued by the United States War Department — or by surgeons’ certificates of disability that had been approved by regimental or more senior ranking Union Army physicians.

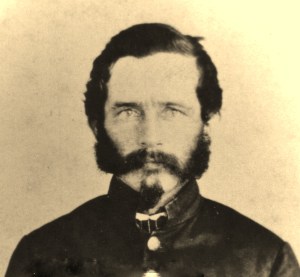

Sergeant-Major William M. Hendricks, central regimental command, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, circa 1863 (public domain).

Among the more startling departures were those of First Lieutenant William M. Hendricks of Company C, Private William Kennedy of Company G, and Private Daniel Kochendarfer (alternate spellings: Kochenderfer, Kochendorfer) of Company H. First Lieutenant Hendricks had simply had his fill of military life and had resigned his commission on May 9, 1865 and Private Kennedy had died from phthisis at Mower General Hospital in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on May 25, but Private Kochendarfer was ordered to remain behind for an entirely different reason — an arrest and conviction (the details of which remain murky to this day).

* Note: Having distinguished himself earlier in his career by nursing his sick and wounded comrades during their final moments of life in 1862, Private Daniel Kochendarfer was convicted during a court martial trial and sent to a federal military prison on June 1, 1865. He remained imprisoned there even as the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry was mustering out for the final time on Christmas Day in 1865. Dishonorably discharged on March 7, 1866, he was never able to clear his name, despite petitioning the U.S. War Department for redress during the 1890s.

Medical Discharges

Other discharges that were issued to 47th Pennsylvanians at Camp Brightwood that spring were granted for entirely different reasons — physical or mental fitness for new duties that would require both brains and brawn. Among those deemed no longer fit to serve were:

- Private George W. Lightfoot of Company G, who was transferred to Company I in the 24th Regiment of the U.S. Army’s Veteran Reserve Corps, which was also known as the “Invalid Corps” (April 25, 1865);

- Private Joseph H. Schwab of Company F, who was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability (April 25, 1865);

- Private William Leinberger of Company C, who was transferred to the 1st Battalion of the 21st Regiment of the Veteran Reserve Corps (April 28, 1865);

- Private William M. Michael of Company C, who had been wounded in action during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1864 and was honorably discharged per General Orders, No. 77, issued by the Office of the U.S. Adjutant General (May 3, 1865);

- Private William H. Guptill of Company G, who was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate of disability (May 15, 1865);

- Private Josiah D. Rabenold of Company B, who had been wounded in action during the Battle of Opequan, Virginia, also known as “Third Winchester,” on 19 September 1864, was treated by Union Army physicians and was honorably discharged (May 15, 1865);

- Private Joseph Young of Company G, who had been hospitalized at a Union Army facility in Cumberland, Maryland and was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (May 17, 1865);

- Private Charles Acher of Company K, who was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (May 19, 1865);

- Private George P. Blain of Company C, who had been wounded in action during the Battle of Cedar Creek and was honorably discharged per General Orders, No. 77, issued by the Office of the U.S. Adjutant General (May 19, 1865);

- Private Adam Lyddick of Company H, who had been severely wounded above the knee during the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia on October 19, 1864 and was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (May 19, 1865);

- Private George Turpin of Company H, who had been hospitalized at the Union’s Mower General Hospital in Philadelphia (May 19, 1865);

- Private Charles Buss of Company F, who had endured captivity as a prisoner of war (POW) at the Confederate Army’s prison camp near Tyler, Texas (Camp Ford) until his release on January 1, 1865 and was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (May 25, 1865);

- Private Joel Michael of Company F was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (May 25, 1865);

- Private Allen L. Kramer of Company B, who was wounded in action during the Battle of Creek, was treated at a Union Army General Hospital in Philadelphia and was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (May 26, 1865);

- Private Charles F. Stuart of Company C, who had endured captivity as a POW at a Confederate Army prisoner of war camp until his release on 4 March 1865 and was honorably discharged (May 29, 1865);

- Private Daniel S. Crawford of Company A, whose leg had been amputated to save his life after being wounded during the Battle of Cedar Creek and was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (May 31, 1865);

- Private Michael Fitzgibbon of Company I, who was initially alleged to have deserted from Camp Brightwood, but had, in reality, been receiving treatment for malaria from Union Army physicians and was honorably discharged (May 31, 1865);

- Private Lewis Brong of Company B, who had developed a chronic medical condition during Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign and was honorably discharged per General Orders, No. 53, issued by the U.S. War Department (June 1, 1865);

- Regimental Quartermaster Francis Z. Heebner, who had endured captivity as a POW at a Confederate Army officers’ prison in Richmond or Danville, Virginia until his release in late February 1865 and was honorably discharged (June 1, 1865);

- Private Jenkin J. Richards of Company E, who had been hospitalized at the Union’s Fairfax Seminary Hospital in Fairfax, Virginia and was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (June 3, 1865);

- Private Augustus Deitz/Dietzof Company H, who had been hospitalized in Washington, D.C. and was honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (June 6, 1865); and

- Private Andrew Mehaffie of Company D, who had also been wounded during the Battle of Cedar Creek and was also honorably discharged on a surgeon’s certificate (June 9, 1865).

Honorable Discharge by General Orders

Per General Orders, No. 53 or General Orders, No. 272, the more able-bodied 47th Pennsylvanians mustering out at Camp Brightwood were:

- Private Richard Ambrum (Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Private George W. Baltozer (Company D, June 14, 1865);

- Private William H. Barber (Company K, June 1, 1865);

- Sergeant Samuel H. Barnes (Company E, June 1, 1865);

- Private Alfred Biege (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Private David K. Bills (Company A, June 1, 1865);

- Private Tilghman Boger (Company K, June 1, 1865);

- Private David Buskirk (Company G, May 26, 1865);

- Private William Christ (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Private Michael Deibert (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Private George Diehl (Company B, May 23, 1865);

- Private William Earhart (Company D, June 1, 1865);

- Corporal William H. Eichman (Company E, June 1, 1865);

- Private Milton A. Engleman (Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Private George Felger (Company E, June 1, 1865);

- Private Isaac Fleishhower (Company A, May 19, 1865);

- Private William Fowler (Company E, June 1, 1865);

- Private Charles H. Frey (Company E, June 1, 1865);

- Musician and Private James A. Gaumer (Regimental Band No. 2 and Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Private Solomon Gildner (Company A, June 1, 1865);

- Private Benedict Glichler (Company K, May 19, 1865);

- Sergeant John W. Glick (Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Private Solomon Gross (Company I, June 2, 1865);

- Private Emanuel Guera (Company H, June 19, 1865);

- Private James Hall (Company H, June 1, 1865);

- Privates Adam and Jacob Hammaker (Company H, June 1, 1865);

- Private William George Harper (Company D, June 1, 1865);

- Private William P. Heller (Company K, June 1, 1865);

- Private Henry Henn (Company G, May 15, 1865);

- Corporal George K. Hepler (Company C, June 1, 1865);

- Privates Levinus and Solomon Hillegass (Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant Henry J. Hornbeck (June 1, 1865);

- Private Ananias Horting (Company H, June 1, 1865);

- Private Daniel Houser (Company E, June 1, 1865);

- Private Joseph Hausman (Company B, June 1, 1865);

- Corporal Benjamin Huntzberger/Hunsberger (Company I, June 2, 1865);

- Private Abraham F. Keim (Company D, May 23 or 28, 1865);

- Musician Simon P. Kieffer (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Private Charles King (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Private David F. Knerr (Company I, June 1, 1865);

- Corporal Daniel J. Kramer (Company I, June 1, 1865);

- Private William H. Kramer (Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Private John J. Lawall (Company I, June 1, 1865);

- Private James Lay (Company H, June 1, 1865);

- Private William Leiby (Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Private George W. Levers (Company E, June 1, 1865);

- Private John F. Liddick (aka John Liddick 2 and John Liddick 3 per Bates’ History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, Company H, June 1, 1865);

- Private William H. Liddick (Company H, June 1, 1865);

- Private James T. Lilly (Company F, May 31, 1865);

- Private August Loeffelman (Company A, June 1, 1865);

- Private George Malick (Company C, June 1, 1865);

- Private Jesse Moyer (Company I, June 1, 1865);

- Private Aamon Myers (Company D, June 1, 1865);

- Private William Noll (Company K, June 1, 1865);

- Private Thomas H. O’Donald (Company A, May 5, 1865);

- Private Andrew J. Osmun (Company B, June 1, 1865);

- Private Abraham Osterstock (Company A, May 5, 1865);

- Private Jacob Paulus (Company A, June 1, 1865);

- Private Washington A. Power (Company D, June 1, 1865);

- Private Israel Reinhard (Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Private Edward Remaly (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Corporal Allen J. Reinhard (Company B, June 1, 1865);

- Private Henry Rinek (Company E, June 1, 1865);

- Private Charles Rohrbacher (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Private Steven Schechterly (Company I, June 1, 1865);

- Private Lewis Schmohl (Company A, June 1, 1865);

- Private Joseph Benson Shaver (Company D, June 1, 1865);

- Private Peter Shireman (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Private Franklin Sieger (Company B, June 1, 1865);

- Private Samuel H. Smith (Company I, June 1, 1865);

- Private John G. Snyder (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Private Erwin S. Stahler (Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Private H. Stoutsaberger (Company H, June 1, 1865);

- George Stroop (Captain, Company D, June 2, 1865);

- Private Charles Stump (Company A, May 15, 1865);

- Private George Sweger (Company H, June 1, 1865);

- Private Samuel Transue, (Company E, June 1, 1865);

- Private Israel Troxell (Company I, June 1, 1865);

- Private Oliver Van Billiard (Company B, May 26, 1865);

- Corporal Walter H. Van Dyke (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- Corporal William M. Wallace (Company H, June 1, 1865);

- Private Daniel H. Wannamaker/Wannermaker (Company I, June 1, 1865);

- Private Cornelius Wenrich/Wenrick (Company C, June 6, 1865);

- Corporal Solomon Wieder (Company G, June 1, 1865);

- Private Andrew J. Williams (Company D, June 1, 1865);

- Private Franklin H. Wilson (Company F, June 1, 1865);

- and Private Daniel S. Zook (Company D, May 17, 1865).

Peacekeeping and Reconstruction

War-damaged houses in Savannah, Georgia, 1865 (Sam Cooley, U.S. Army, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As spring gave way to summer, the new mission of the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry would be to keep the peace across the United States of America’s Deep South while helping to rebuild shattered communities and restore local government operations during what has since become known as the Reconstruction Era. They arrived at their first new duty station (Savannah, Georgia) during the first week of June in 1865. Promotions during the Camp Brightwood and Reconstruction periods of duty were awarded to:

- Adams, William (Company E): From corporal to sergeant, May 1865;

- Brown, Amos T. (Company H): From private to corporal, June 2, 1865;

- Bush, James M. (Company F): From private to corporal, April 25, 1865;

- Clay, George W. (Company D): From second lieutenant to first lieutenant, June 2, 1865);

- Cunningham, Robert (Company F): From private to corporal, June 2, 1865;

- Dennis, Henry T. (Company G): From sergeant to first sergeant, May 14, 1865;

- Eisenhard, John H. (Company B): From private to corporal, April 21, 1865;

- Haltiman, William H. (Company I): From first sergeant to second lieutenant, May 27, 1865;

- Hartzell, Israel Frank (Company I): From private to corporal, June 2, 1865;

- Hettinger, Stephen (Company I): From private to corporal, June 2, 1865;

- Hinckle, Willam H. (Company K): From private to corporal April 21, 1865;

- Jacoby, Moses (Company E): From private to corporal, June 2, 1865;

- Jones, John L. (Company F): From corporal to sergeant, June 2, 1865);

- Kosier, George (Company D: From first lieutenant to captain, June 1, 1865);

- Kuder, Owen (Company I): From private to corporal, June 2, 1865;

- Lawall, Allen D. (Company I): From second to first lieutenant, May 30, 1865;

- Lilly, Joseph M. (Company F): From corporal to sergeant, April 21, 1865;

- Mayers, William H. (Company I, alternate surname spellings: Mayer, Meyers, Moyers; listed in Bates’ History of Pennsylvania Volunteers as “William H. Moyers I”): From sergeant to first sergeant, May 27, 1865;

- Mink, Theodore (Company I): From first lieutenant to captain, May 22, 1865;

- Moser, Owen (Company E): From private to corporal, May 27, 1865;

- O’Brien, Martin (Company F): From private to corporal, April 25, 1865;

- Rader, Reuben E. (Company A): From private to corporal, May 14, 1865;

- Rockafellow, William (Company E): From corporal to sergeant, June 2, 1865;

- Seneff, Henry (Company C): From private to corporal, April 22 1865;

- Small, Charles H. (Company H): From company private to regimental quartermaster sergeant, June 2, 1865;

- Stuber, Levi (Company I): From company captain to regimental major and third-in-command, May 22, 1865;

- Walton, John F. (Company E): From private to corporal, May 1, 1865; and

- Weise, Henry C. (Company H): From private to corporal, June 2, 1865.

Sadly, while all of those advancements in rank were occurring, Private Allen Faber of Company A, was fighting a battle that he was destined to lose. Still hospitalized for treatment of rheumatic carditis at the Union’s Harewood General Hospital in Washingon, D.C, he finally succumbed there to complications from his condition on June 7, 1865, and was subsequently interred with military honors at the Arlington National Cemetery in Arlington, Virginia.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Battleground National Cemetery: Battleround to Community — Brightwood Heritage Trail,” “Fort Stevens” and “Mayor Emery and the Union Army.” United States: Historical Marker Database, retrieved online May 20, 2025.

- “Battleground to Community: Brightwood Heritage Trail.” Washington, D.C.: Cultural Tourism DC, 2008.

- Civil War Muster Rolls (47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1866 (47th Pennsylvania Infantry). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- “Our Returned Prisoners: Names of 500 Released Officers Sent to Annapolis.” New York, New York: The New York Times, February 28, 1865.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

You must be logged in to post a comment.