War-damaged houses in Savannah, Georgia, 1865 (Sam Cooley, U.S. Army, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

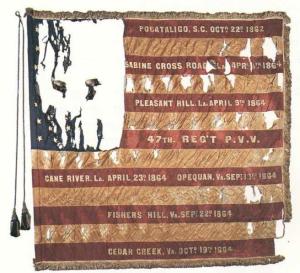

Stationed in Savannah, Georgia since June 7, 1865, the soldiers still serving with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry that first summer after the American Civil War were assigned to provost duties — as peacekeepers, public information specialists and public works officials, during what has since become known as the Presidential Reconstruction Era (1865-1867) of American History.

Commanded by Colonel John Peter Shindel Gobin, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles William Abbott and Major Levi Stuber, multiple members of the regiment were literally involved in the re-construction of small southern towns and larger cities, helping to shore up war-damaged structures that could be restored — and in tearing down others that were deemed too dangerous for civilians to leave standing.

It was hazardous work, according to John Young Shindel, M.D., an assistant regimental surgeon who had joined the medical staff of the 47th Pennsylvania earlier that same year. On Wednesday, June 18, 1865, he noted that:

10 o’clock wall fell in and buried 15 or 20 men. 6 or 7 were taken out some dead. Zellner Co. K badly hurt. Sent him to Hosp. Capt. Hoffman, Chief of Police, seriously hurt. In P.M. was with Capt. Hoffman.

The 47th Pennsylvanian mentioned by Dr. Young was Private Ben Zellner, who had survived repeated battle wounds and confinement as a prisoner of war (POW) at two Confederate States Army prison camps, only to nearly lose his life while assigned to police duty during peacetime. According to Private Zellner’s 1896 account of that 1865 accident, his jawbone had been broken during the wall’s collapse “and he sustained 11 scalp wounds”; as a result, he “lost the sight of his left eye and the hearing of his left ear.”

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry’s Regimental Band performed in concert for James Johnson, provincial governor of the State of Georgia, at the Pulaski Hotel in Savannah on June 30, 1865 (Pulaski Hotel, Savannah, Georgia, circa 1906, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

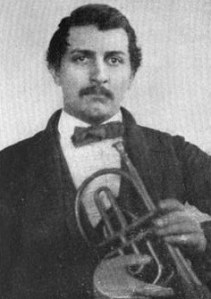

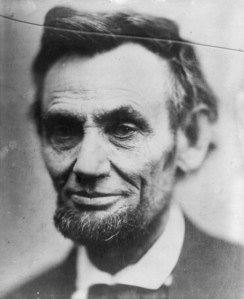

Meanwhile, other 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were being transformed into diplomats. Officers and enlisted members of the regiment, for example, helped to facilitate a warm welcome for James Johnson, the provisional governor of Georgia, during his official visit to Savannah in early July. According to the Charleston Daily Courier, Governor Johnson (who had been appointed to his gubernatorial post by U.S. President Andrew Johnson (but was not related to the president), had been invited to Savannah by members of the city council “to address the citizens … at some suitable place.” In that invitation, council members also suggested that “military and naval commanders of the United States army and navy at this post and their respective staffs be respectfully invited to attend said meeting.” Johnson subsequently accepted the invitation and made the trip to Savannah in late June. The night of his arrival (June 30), “the fine band of the 47th Pennsylvania Regiment, Eugene Walter, Leader, serenaded the Governor at the Pulaski House.”

Several patriotic airs were played, and as soon as practicable the Governor appeared on one of the balconies, in response to repeated calls. He was loudly welcomed. He made no elaborate speech, but addressed the immense assembly substantially as follows:

“Fellow-Citizens — I thank you for the consideration, on your part, which has occasioned this demonstration. I know that you have called on me as the Provisional Governor of the State of Georgia, and in the discharge of the high duties now incumbent upon me, I promise you to act to the best of my ability. I know that you will not expect, on this occasion, any very full remarks. Hoping to meet you hereafter, and then to have an opportunity to explain my sentiments and position, I will bid you good night.”

This brief address was received with loud cheers by the crowd, and the band then played several other appropriate airs.

On July 1, the Savannah Republican newspaper published a more detailed description of that evening’s events:

Last evening, through the exertions of a few citizens, an impromptu call was made upon Gov. Johnson at the Pulaski by a delegation of loyal men, accompanied by the fine band of the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, now stationed in this city. The object of the call was simply to manifest the joy of the people at the return of a loyal civil magistrate, who, in a measure, holds the future destiny of Georgia in his hands, and to pay the Governor the compliment of a serenade. After the band had performed several appropriate pieces of music, loud calls and cheers were given for the Governor, who at length appeared, and in a few brief remarks thanked the assemblage for their demonstrations of respect, and informed them that, being wearied with traveling he begged to be excused from making any formal speech. Before bidding the crowd good night, the Governor informed them that it would be his pleasure to address the people tonight at the Theatre, where he would state his position and give his views on the state of the country. Upon retiring, the crowd applauded and cheered the Governor lustily, while Johnson square was ablaze with the discharge of fire works, the shooting of rockets, roman candles, and the illumination of blue lights, gave the scene a very brilliant appearance and made the vicinity of Savannah lively for one hour. At a late hour the crowd quietly dispersed to their homes, well pleased with the impromptu ovation to the Governor. Governor Johnson was afterwards introduced to a large number of army officers, each of whom expresses the wish that the day was near when bayonets would not be necessary to maintain order in Georgia. The Governor, who is a most unostentatious gentleman, spoke very encouragingly of the future, and shook hands with all who were introduced.

The thanks of our citizens are due Colonel Gobin, of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, for the services of his excellent band, whose presence made the hasty reception a success. The Colonel has very kindly offered the use of his band for the meeting this evening at the theatre, and we may expect a brilliant gathering of the masses tonight at 8 o’clock.

James Johnson, provisional governor of the State of Georgia, 1865 (Lawton B. Evans, A History of Georgia for Use in Schools, 1898, public domain).

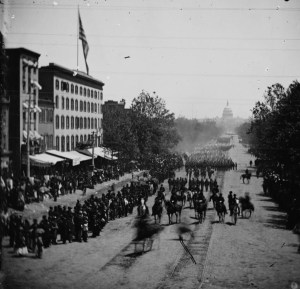

On Saturday evening (July 1), Governor Johnson fulfilled his promise. During a lengthy address, he spoke about cooperation and the rule of law, the true meaning of citizenship and the path forward following the nationwide eradication of chattel slavery. The crowd, which had been attentive throughout his speech, gave him a robust round of applause, and peacefully dispersed, according to subsequent newspaper reports. The festivities, which continued into the next week, also included a “Grand Review of the Garrison,” which was held in Savannah on Monday afternoon, July 3. According to the Savannah Republican:

The review of the entire garrison by Major General H. W. Birge, on Monday afternoon, was certainly one of the finest military pageants that we have witnessed since the departure of Gen. Sherman’s army. For perfection of military movements, neatness of appearance and true soldierly bearing on the part of privates as well as officers, won encomiums from the vast crowd of spectators who witnessed the review. We don’t blame Gen. Birge to feel proud of such a noble body of gallant men as he has the honor to command, and we are fortunate in having so excellent a command garrisoning our city.

The following composes the troops that participated in the review:

Brigadier General Joseph D. Fessenden, commanding 1st Division.

1st Brigade, 1st Division, Col. L. Peck commanding. — 90th New York, Lt. Col. Schamman; 173d New York, Lt. Col. Holbrook; 160th New York, Lt. Col. Blanchard; 47th Pennsylvania, Col. Gobin.

2d Brigade, Col. H. Day commanding. — 131st New York, Capt. Tilosting commanding; 128th New York, Capt. _____ ; 14th New Hampshire, Lt. Col. Mastern.

3d Brigade, 2d Division, Col. Graham commanding. — 22d Iowa, Lt. Col. _____ ; 24th Iowa, Lt. Col. Wright; 28th Iowa, Lt. Col. Wilson.

4th Brigade, Brevet Brig. Gen. E. P. Davis commanding. — 153d _____ , Lt. Col. Loughlin; 30th Maine, Col. Hubbard; 12th Connecticut, Lt. Col. Lewis; 26th Massachusetts, Lt. Col. Chapman; 75th New York, Lt. Col. York; 103rd U.S.C.T., Major Manning.

Civil conversation, community concerts and displays of kindness toward strangers were indeed replacing bayonets — becoming the most powerful tools ever wielded by the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers as they helped to rescue their nation from disunion.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1865-1, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Comrade Zellner’s Birthday” (includes description of Private Benjamin F. Zellner’s injury in 1865 while serving with the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the Reconstruction Era). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, March 27, 1896.

- Evans, Lawton B. A History of Georgia for Use in Schools, p. 304. New York, New York: Universal Publishing Company, 1898.

- Foner, Eric. “Reconstruction.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online July 1, 2025.

- “Governor Johnson’s Patriotic Address: A Stirring Appeal to Georgians.” Savannah, Georgia: Savannah Republican, July 6, 2025.

- “House Divided: The Civil War Research Engine at Dickinson College.” Carlisle, Pennsylvania: Dickinson College, accessed July 1, 2025.

- “James Johnson,” in New Georgia Encyclopedia. Atlanta, Georgia: Georgia Humanities, retrieved online July 1, 2025.

- “Savannah Intelligence.” Charleston, South Carolina: Charleston Daily Courier, July 4, 1865.

- “Serenade to Our New Governor: The Pulaski House and Johnson Square Radiant with Fireworks: Remarks of the Governor: Music and Pyrotechnics.” Savannah, Georgia: Savannah Republican, July 1, 1865.

- Shindel, John Young. Diary and Personal Letters, 1865-1866. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Personal Collection of Lewis Schmidt.

- Wharton, Henry D. Letters from the Sunbury Guards, 1865. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1865-1866.

- “The Grand Review of the Garrison.” Savannah, Georgia: Savannah Republican, July 6, 1865.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, July 20, 1870.

You must be logged in to post a comment.