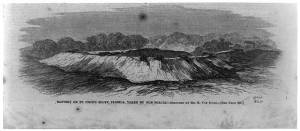

Shenandoah Valley from Maryland Heights (Alfred R. Waud, 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain). For Waud’s own description of this work, click here.

By 1864, Federal control of the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia was viewed as necessary to a Union victory because of the Valley’s configuration and its economic potential to the Confederate war effort. The Valley’s alignment from southwest to northeast made it an excellent Confederate avenue of approach, threatening Federal resources in Maryland, Pennsylvania, and of course, Washington, D.C., itself. The excellent road system, including the hard-surface Valley Pike (US 11), allowed rapid movement into vulnerable Federal areas…. The area had continued to produce a large portion of the food required by Lee’s army in eastern Virginia as well as that needed in other parts of the Confederacy. Unfettered access to the Valley put the produce of nearby parts of Maryland and Pennsylvania within Confederate reach as well. — Joseph Whitehorne, The Battle of Cedar Creek

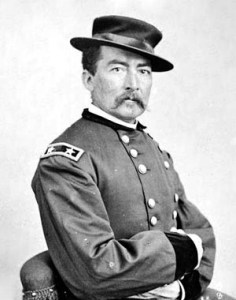

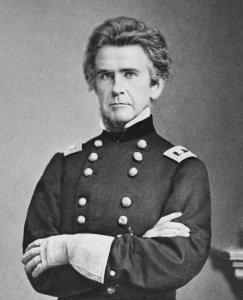

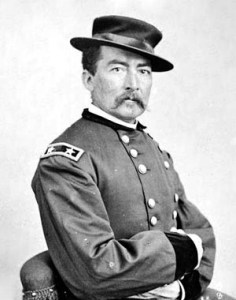

Following Washington, D.C.’s close brush 11-12 July 1864 with Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s advancing Confederate army, that army’s 30 July burning of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, and Union General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant’s consequent summer 1864 shakeup of top military leaders, which included his appointment of Major-General Philip H. Sheridan as head of the U.S. Middle Military Division and its Army of the Shenandoah, the stage was set for the Civil War’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign—a series of battles that tipped the scales of victory sharply in favor of the Federal Government during the fall of 1864, and ensured the reelection of Abraham Lincoln to his final, fatal term as president of the United States of America.

Among the players in this intense drama were Confederate army leaders described by historian Jeffry Wert as “some of the finest combat commanders in Virginia.” Their Union opponents were equally impressive. According to Wert:

Union authorities, finally, had brought to the Shenandoah Valley a command – in strength, leadership and combat prowess – worthy of the strategic value of the region. The Army of the Shenandoah exceeded, in numbers alone, any previous Union force in the Valley. Sheridan would begin the forthcoming campaign with nearly 35,000 infantry and artillery effectives and 8,000 cavalry. If the separate Military District of Harpers Ferry, commanded by Brigadier General John D. Stevenson, numbering nearly 5,000, were included, Sheridan had, at hand, approximately 48,000 troops. His Middle Military Division also embraced the nearly 29,000 troops in the Department of Washington, the 2,700 soldiers in the Department of the Susquehanna and the approximately 5,900 Federals in the Middle Department.

Even more striking was the Federal Government’s charge to those Union troops. On 5 August 1864, Grant wrote to Sheridan, urging:

In pushing up the Shenandoah Valley, where it is expected you will have to go first or last, it is desirable that nothing should be left to invite the enemy to return. Take all provisions, forage, and stock wanted for the use of your command; such as cannot be consumed, destroy. It is not desirable that the buildings should be destroyed – they should rather be protected; but the people should be informed that, so long as an army can subsist among them, recurrence of these raids must be expected, and we are determined to stop them at all hazards.

Bear in mind, the object is to drive the enemy south…. Make your own arrangements for supplies of all kinds, giving regular vouchers for such as may be taken from loyal citizens in the country through which you march.

The day after Grant penned that directive—6 August 1864—the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry crossed over the Potomac River at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia. Still attached to the 19th U.S. Army Corps of Brigadier-General William Emory (the corps and senior commanding officer to which and to whom they had been attached in Louisiana), the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were preceded and followed, respectively, by troops commanded by Brigadier-Generals George R. Crook and John B. Ricketts.

* Note: On 7 July 1864, while stationed in New Orleans, the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry was temporarily separated into two detachments when the soldiers assigned to the regiment’s Companies B, G and K were ordered to remain behind in Louisiana to await transportation north following the end of the Union’s Red River Campaign while the men from Companies A, C, D, F, H, and I steamed aboard the McClellan for the Washington, D.C. area. That group of 47th infantrymen then had a memorable encounter with President Abraham Lincoln at Fort Stevens (situated just outside of the nation’s capital) on 12 July, and joined in fighting in and around Snicker’s Gap, Virginia (also known as the Battle of Cool Spring) in mid-July under the command of Union Major-General David Hunter and Brigadier-General William Emory. Both detachments from the 47th Pennsylvania were ultimately reunited on 2 August at Monocacy, Virginia, and were then ordered on to Harper’s Ferry and Halltown, Virginia.

Halltown Ridge, looking west with “old ruin of 123 on left. Colored people’s shanty right,” where Union troops dug in after Major-General Philip Sheridan took command of the Middle Military Division, 7 August 1864 (photo and caption: Thomas Dwight Biscoe, 2 August 1884, courtesy of Southern Methodist University).

Ordered to march next for Halltown, Virginia, the 47th Pennsylvanians were assigned, upon arrival, to defensive duties. Union Major-General David Hunter “took up his position covering Halltown and proceeded to strengthen its entrenchments,” according to historian Richard Irwin, while “Crook’s left rested on the Shenandoah, Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] extended the line to the turnpike road, and Wright carried it to the Potomac.”

According to the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation, as Sheridan was bolstering Union positions in Virginia, Lieutenant-General Jubal Early was reinforcing his Confederate positions with the Confederate States of America troops under his command:

Early deployed his forces to defend the approaches to Winchester, while Sheridan moved his army, now 50,000 strong, south via Berryville with the goal of cutting the Valley Turnpike. On August 11, Confederate cavalry and infantry turned back Union cavalry at Double Toll Gate in sporadic, day-long fighting, preventing this maneuver.

Robert E. Lee sent reinforcements under the overall command of Gen. Richard Anderson to join Early. On August 16, Union cavalry encountered this force advancing through Front Royal, and in a sharp engagement at Guard Hill, Gen. George A. Custer’s brigade captured more than 300 Confederates.

Sheridan had been ordered to move cautiously and avoid a defeat, particularly if Early were reinforced. Uncertain of Early’s and Anderson’s combined strength, Sheridan withdrew to a defensive line near Charles Town to cover the Potomac River crossings and Harpers Ferry. Early’s forces routed the Union rear guard at Abrams Creek at Winchester on August 17 and pressed north on the Valley Turnpike to Bunker Hill. Judging Sheridan’s performance thus far, General Early considered him a timid commander.

On August 21, Early and Anderson launched a converging attack against Sheridan. As Early struck the main body of Union infantry at Cameron’s Depot, Anderson moved north from Berryville against Sheridan’s cavalry at Summit Point. Results of the fighting were inconclusive, but Sheridan continued to withdraw. The next day, Early advanced boldly on Charles Town, panicking a portion of the retreating Union army, but by late afternoon, Sheridan had retreated into formidable entrenchments at Halltown, south of Harpers Ferry, where he was beyond attack.

Early then attempted another incursion into Maryland, hoping by this maneuver to maintain the initiative. On August 25, two divisions of Sheridan’s cavalry intercepted Early’s advance, but the Confederate infantry drove them back to the Potomac. Early’s intentions were revealed, however, and on August 26, Sheridan’s infantry attacked and overran a portion of the Confederate entrenchments at Halltown, forcing Anderson and Kershaw to withdraw to Stephenson’s Depot. Early abandoned his raid and returned south, establishing a defensive line on the west bank of Opequon Creek* from Bunker Hill to Stephenson’s Depot.

On August 29, Union cavalry forded the Opequon at Smithfield Crossing but were swiftly driven back across the creek by Confederate infantry. Union infantry of the VI Corps then advanced and regained the line of the Opequon. This was one more in a series of thrusts and parries that characterized this phase of the campaign, known to the soldiers as the “mimic war.”

Regimental records confirm back-and-forth movements by the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers during this “mimic war” with a fair degree of confusion regarding dates of departure and arrival at various camp sites. According to historian Lewis Schmidt, “On Wednesday [10 August], the regiment marched from Halltown, as Company K recorded it ‘left Halltown and marched to Middletown and back to Halltown and skirmished.’” On the 11th, “the 47th left its bivouac near Berryville and marched to Middletown where it arrived the next day,” and remained there for several weeks before returning to Halltown where, according to Schmidt, “it arrived on August 20.”

The clerks from C Company, however, noted that the regiment left Middletown for Winchester, departing on Monday, 15 August and arriving the next day. By Wednesday, they then recorded the 47th as heading for Berryville.

In a letter home to the Sunbury American newspaper, 47th Pennsylvanian Henry D. Wharton provided a more detailed chronology, while also offering vital insights into what life was like for Virginians trapped between opposing armies—and what it had been like for members of his regiment who had been held as prisoners of war (POWs):

20 August 1864

Letter from the Sunbury Guards.

CAMP NEAR CHARLESTON, VA. }

August 20, 1864.

DEAR WILVERT : –

Since I wrote to you last, we have had weary marches and travelled many miles after the Johnnies, but as yet have not met them in a regular battle. Since the 10th of this month, Gen. Sheridan has done his best to catch and whip the rebels, but their fleetness and the peculiarity of the country, in the way of mountains and gaps, is such that he is now no nearer that object than when our march commenced. Our cavalry drove the reel videttes often while on our march towards Winchester, and every day, in skirmishes, compelled the graybacks to run for safety. Early was forced to retreat to the mountains beyond Strasburg, where he threw up intrenchments [sic], hoping to draw our army into a trap, but our commander knowing the position he held, and the almost impossibility of driving the enemy from the gap, did not advance further than Cedar creek with the main army, and then sent the cavalry to commence operations, by trying to draw him out into an open field and fair fight. This they accomplished on last Tuesday [16 August] having as Gen. Sheridan reports ‘a brilliant affair,’ in which the rebels lost severely in killed, wounded and prisoners. In this fight the rebs crossed a stream and made a charge; they were repulsed and in recrossing, besides the killed, many were taken prisoners, the cavalry boys saying ‘come back, or we will shoot. This command was readily obeyed, the Johnnies thinking like Capt. Scott’s coon, ‘not to shoot and they would knock under.’ The enemy were forced back to Front Royal, when they were reinforced by two Divisions of Longstreet’s corps, from Richmond. Our force then fell back to the creek, when a sharp artillery duel came off. Not making anything out of this, Sheridan fell further back, trying to coax the enemy from his earthenworks and the stronghold of the mountain. This, the Confed leaders would not accept, so Sheridan moved part of his forces back to Winchester, then to Berryville, keeping, however, his army so fixed that there could be no danger of surprise, and finally to this camp, two miles from Charlestown, where every preparation is made for a fight, and the great wish now is that the rebel horde will make their appearance in force, so that the strife may end in the valley, and that we may so effectually use them up that there will be an end to the raids into Pennsylvania and Maryland.

On our route from Berryville to Middletown, we passed a farm house, on the porch of which, were three gaily dressed young ladies. They laughed and chatted with the boys, offering them water, and made themselves generally agreeable. Not suspecting anything wrong, the most of our corps passed by, when a little brother allowed ‘there was some soldiers in the house.’ The Provost Marshal thought it advisable to examine the premises, and by so doing found concealed under beds, three rebel officers and seven privates. These gentlemen were at work threshing grain, and our skirmishers coming on them so quickly they could not get away, so they sought the house for shelter thinking by this ruse of the young ladies donning their ‘best bib and tucker,’ they could elude the vigilance of the Yanks and escape. They were mistaken and ere you get this, these chivalrous gentlemen will be in durance vile, guarded by Uncle Abe’s pets.

Charlestown is not the place it was three years ago, when we were encamped there as three months men. Then business was brisk, stores filled with goods and open to purchasers, the streets crowded with men, and the open windows showed the faces of many beautiful women, some of whom wore smiles and appeared happy, while others played the part of the virago and spat at our boys as they passed on the side walk. Now misery and want are visible, stores closed, signs displaced, streets deserted, buildings burned and everything indicates that these once happy people, what are left, are brought to poverty, if not starvation. Winchester has been a right smart place, having all the modern improvements, such as gas, water works, &c. The buildings are really fine and the streets well paved. It is situated in a splendid valley and must have been a place of considerable business. But like its sister, Charlestown, war and battle has had effect on it; and now it is but a ‘deserted village.’

A cavalry train was attacked at Berrysville [sic], a few days ago, by Moseby’s [sic] men, just as they were coming out of the park. The guard (hundred day men) were surprised and fled, leaving arms, &c., in the confusion. The wagons, about fifty, were burned and two hundred mules captured. A scouting of cavalry hearing the firing, immediately started to the rescue, and arrived in time only to give chase to the guerrillas who were notified of the whereabouts of the train by a citizen; who, for his part was hung as a spy. This spy made a speech acknowledging his guilt, giving his reasons for the act, and then most pittifully [sic] begged for his life. It was all of no avail, for the facts were so positive that hesitance to carry out the sentence would have been criminal. He had been under arrest twice before, but managed to escape. This time he was caught in citizens [sic] dress, having been but a short time before seen a rebel uniform, in fact, about the time the train was attacked. Papers were found on him addressed to Longstreet, giving a particular account of our forces, the amount of infantry, artillery and cavalry, and, besides, he was identified by an Adjutant, whom he, the spy, had stood guard over while he was in Libby prison. He had the spiritual advice of three Chaplains, and was baptized shortly before his execution.

Several promotions have been made lately in the 47th Pa.Vols., the most prominent of which is Capt. J. P. S. Gobin, to that of Major. This appointment is well deserved and is the unanimous choice of the Regiment. The members of Co. C., for their own good, are opposed to losing their Captain; but for his advancement are well pleased, and consider what is their loss is gain to the regiment.

The members of Co. C., that were taken prisoners in the battle on the Red river, have been paroled or exchanged, with the exception of John C. Sterner, and are now at their homes on furlough or in hospitals at New Orleans. While at Tyler, Texas, [Camp Ford] they were vaccinated or innoculated [sic], with impure matter which impregnated their blood and now they are afflicted with ulcerated limbs and sore eyes. The fiends, pretending to give these men a preventive for small pox, filled their systems with a loathsome disease that will cling through life. Is not this an inhuman act? Samuel Miller is in the hospital at New Orleans.

An attack is hourly expected. Our forces are in position ready to receive the enemy. If a battle comes off, and I am lucky, I will send you particulars. The boys are well. With respects to all in the office, yourself and friends, I remain,

Yours, Fraternally,

H.D.W.

“On Wednesday [31 August], correspondence and a regimental return indicated the 47th was located near Charlestown,” according to Schmidt, and “the 47th was paid this date by a Major Eaton. Various members of the band were paid by the 47th’s Council of Administration effective through this date, generally for a three to four month period. The men and accounts are as follows: Anthony B. Bush, $157.50; Eugene Walters [sic] and John Rupp, each $100; David Gackenback [sic], $52.50 Henry Kern and George Frederick, each $60; Henry Tool [sic], $30; and Lewis Sponheimer, Harrison Handwerk, Edwin Dreisbach, Daniel Dachradt [sic] and William Heckman, each $16.”

A Busy First Week of September — The Battle of Berryville, Virginia

During the opening days of September 1864, the sparring between Union and Confederate forces continued, and the regimental command of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers was reshuffled yet again.

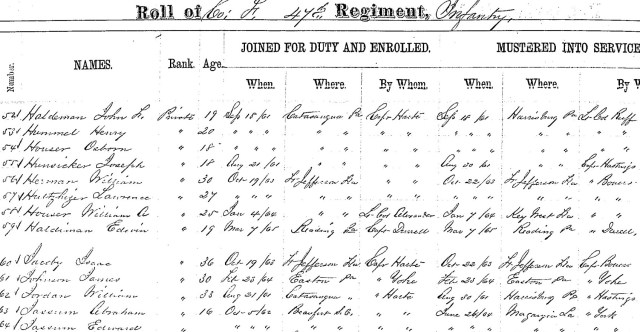

Among those moving up the ranks on 1 September 1864 were regimental Sergeant-Major William M. Hendricks, who advanced to first lieutenant with the regiment’s central command staff; E Company Private Washington Scott Johnston, who was promoted to the rank of first lieutenant and adjutant and transferred to the regiment’s central command staff; B Company’s Charles H. Martin, who advanced from private to first sergeant; C Company First Lieutenant Daniel Oyster, who was commissioned as captain, and placed in command of his unit; C Company’s First Sergeant Christian S. Beard, Sergeant William Fry, Private John Bartlow, and Private Timothy Matthias Snyder who advanced, respectively, to the ranks of second lieutenant, first sergeant, sergeant, and corporal; and F Company’s First Sergeant William Hiram Bartholomew, who was advanced to the rank of first lieutenant within his unit.

“Personnel records for the period” also showed that “many members of the regiment were due the 4th installment of their $402 bounty,” according to Schmidt:

The records of Privates Tilghman Ritz and Lewis Seip of Company B include, ‘due $6 increased pay for months of May-June’ as the pay rates for Privates were increased from $13 to $16 per month; records of Pvt. Charles Schaeffer of Company E list ‘stoppage for trans $10.80’; remarks in the records of Pvt. Christian Smith of Company G include ‘C.P.M.G.O. due $6 increased pay for May-June’; and Pvt. Daniel Kochendorfer of Company H ‘1st install bounty due $50’….

“Berryville from the West. Blue Ridge on the Horizon,” according to T. D. Biscoe, who photographed the Berryville Pike on 1 August 1884—two decades after the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers fought in this vicinity (photo courtesy of Southern Methodist University).

Marching from Halltown during the opening days of September 1864, Sheridan’s troops arrived at Berryville on Saturday, 3 September. Meanwhile, that same day according to Schmidt, the 47th Pennsylvania’s “Company I reported that it [also had] left camp near Charlestown and marched to Berryville.”

Before they could even put their tents in place, however, a portion of Sheridan’s troops were forced to repel an attack by Major-General Joseph B. Kershaw’s division of Confederate States of America troops on a Union grouping led by Brigadier-General George Crook. Motivated by CSA Lieutenant-General Early’s orders to move additional Confederate troops into the area, the attack was led by CSA Major-General Richard H. Anderson. According to the Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation:

On September 2-3, Averell’s cavalry division rode south from Martinsburg and struck the Confederate left flank at Bunker Hill, defeating the Confederate cavalry but being driven back by infantry. Meanwhile, Sheridan concentrated his infantry near Berryville. On the afternoon of September 3, Anderson’s command encountered and attacked elements of Crook’s corps (Army of West Virginia) at Berryville but was repulsed. Early brought his entire army up on the 4th, but found Sheridan’s position at Berryville too strongly entrenched to attack. Early again withdrew to the Opequon line.

General Crook’s Battle Near Berryville, Virginia, September 3, 1864 (James E. Taylor, public domain; click to enlarge).

On 5 September 1864, Captain Daniel Oyster of the 47th Pennsylvania was wounded in action in the left shoulder in a post-battle skirmish. Two days later, C Company scribe Wharton provided the following details about the Battle of Berryville and its aftermath:

7 September 1864

Letter from the Sunbury Guards.

NEAR BERRYVILLE, VA., }

September 7, 1864.

DEAR WILVERT:

For several days after the army had advanced up this valley, the men were busily engaged in building intrenchments [sic] and fortifying their position, two miles west of Charlestown. During the entire night and the whole next day were the boys at work with the shovel and pick, carrying rails, &c., building breastworks for the protection of the regiment, and scarcely was the job finished, the bright spade put aside, when ‘fall in’ was heard, and the 47th was moved to another place to build other earthworks. – This they done [sic] cheerfully, knowing the work was necessary; and that it was for their own protection. The position held by our army, at that point, was excellent, and so well arranged was [sic] our defences, that an attack made on us by the enemy would have been disastrous to him, and added another list to the name of Union victories. The enemy knew this, and after finding out Sheridan’s strength fell back towards Winchester, keeping his head quarters [sic] at Bunker Hill. Our forces on last Saturday morning [3 September], then broke up camp, following them to within one mile of this place, where we found signs of the Johnnies. The 8th corps, Gen. Crooks [sic], commanding, was, in the advance who rested in line of battle, with arms stacked, for a couple of hours, while pickets were being posted. After the pickets had been established this command went into camp, and had just finished pitching their tents, which was about four o’clock P.M., when heavy skirmishing was heard on the picket line. The whole command was rapidly turned out and formed, and moved to the support of the pickets, who had been driven from behind some intrenchments [sic], which they had occupied.

From the correspondent of the Baltimore American, I learn the following facts of the fight:

The 36th Ohio and 9th Virginia were formed, and charged the enemy, driving then out of the entrenchments. A desperate struggle now ensued, the rebels being determined, if possible, to regain possession of these entrenchments. With this object in view they massed full two divisions of their command and hurled them with their accustomed ferocity against our gallant little band, who were supported by both Thoburn’s and Duvall’s division. They were handsomely repulsed every time they changed, the conflict lasting long after the sun had sent, and artillery firing being kept up until 9 o’clock.

Our loss was about three hundred killed and wounded that of the enemy, from good information, was at least one-third greater, besides fifty prisoners and a stand of colors.

While the fight was going on, the 6th and 19th corps were pushed forward and took up several lines, but not being needed, did not share in the punishment given the rebels. On the next day, Sabbata [sic], the pickets had hard work and done a great deal of firing with the enemy. A member of Company C., to which I belong, told me he fired fifty-three rounds at them. What punishment was inflicted I cannot tell you, on the part of the Johnies sic], but to our men, I know it was small; two men of the 47th wounded by the same ball, and they slightly.

On Monday [5 September] the 47th was out on a reconnoisance [sic]. Four companies were in advance as skirmishers, who soon were received by a shower of bullets from the graybacks. This did not, in the least deter them, for they gave as good as they got, and with the regiment pushed on driving the enemy before them. The main portion of the regiment dare not fire, for if they did, the shooting of our own men who have been the consequence, so they stood the whizzing of bullets about their ears, as well as could be expected, under the circumstances. In this work two members of Co., C., were wounded. David Sloan, flesh wound in right arm from a minnie ball, and Benjamin McKillips in right hand. These wounds are slight, but at the present time somewhat painful, not so much so, however, as to prevent them enjoying that great luxury of a soldier – sleep. Capt. Oyster was struck by a ball, staggering him, but otherwise doing no injury. In his being hit there is a circumstance connected, that I cannot help but giving you, even you may put it down as a fish story, though for the truth the whole company will vouch. The ball struck him on the back of his shoulder, made a hole in his vest and shirt and none in the coat. Two members of Co. K., were wounded – one of them has since died.

The whole army have [sic] been busily engaged in digging intrenchments [sic], and throwing up breastworks, and now occupy a very strong position. Whether there will be an engagement here, or what the movements are to be, I can form no opinion, for if there was a General ever kept his thoughts, Sheridan is the one, and it is an impossibility to find out anything until it is completed. For material to write on, one is continued to his own Brigade, and there is so much sameness in that, that it would be but a repetition to send it to you. If I were to take down the ‘thousand and one’ rumors that daily come into camp, I could fill columns of the American, weekly, but as I prefer facts, I hope you will be satisfied if I send you news semi-occasionally.

I wrote to you a few days ago of the promotions in Company C, but for fear they did not reach you, I send them again: Daniel Oyster, Captain; William M. Hendricks, 1st Lieutenant; and Christian S. Beard, 2nd Lieutenant. They are well liked, and in their new positions give satisfaction. With the exception of the wounded, the boys are well, perfectly contented with their lot, only that they have a great hankering for the greenbacks that is [sic] due to them. Those, it is said, will be forthcoming in a few days. With respects to yourself, family and old friends, I remain,

Yours, Fraternally,

H. D. W.

* Note: According to reports by the regiment, as well as members of the 29th Maine Volunteers, the 47th Pennsylvania incurred a total of eight casualties—seven who were wounded (including Private David Sloan of C Company), and one—Private George Kilmore, of K Company, who died the same day of the battle (5 September) from the gunshot wound to his abdomen. When he started the day, he had had just two weeks left to serve on his three-year service term.

With respect to Captain Oyster’s gunshot wound (usually noted on Civil War medical records as Vulnus Sclopet), Wharton was somewhat off in his assessment. Oyster required medical attention after being struck in the left shoulder and, although he recuperated and returned to lead his unit once again before the month was out, that shoulder wound and another suffered later prompted him to seek less strenuous employment after the war.

Winchester, Virginia (circa 1862, U.S. Army, public domain).

Records completed by Company B personnel immediately after the Battle of Berryville documented the 47th Pennsylvania’s continued skirmishes with the enemy—this time at Winchester on Wednesday, 7 September. According to Schmidt, around this same time, “Regimental Order #58, at camp near Berryville, detailed five men to daily duty with the ambulance corps. They were to report to Surgeon John Homans,” who “was not with the 47th.” Three days later, an additional five men were shifted to the ambulance corps via Regimental Orders, No. 59.

On 11 September, a Sunday, additional personnel changes were made when F Company’s Second Lieutenant Augustus Eagle resigned his commission, and Private Benjamin F. Bush was promoted to the rank of corporal—and then, within a week, to sergeant.

The grueling marches by the regiment in hot weather and continued close living in frequently unsanitary conditions also continued to thin the 47th’s ranks as men were felled by everything from dysentery to sunstroke. On 15 September, B Company Private Jacob Apple died from apoplexy at the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental hospital at Berryville, Virginia; his death was certified by the 47th’s Assistant Surgeon, William F. Reiber, M.D.

Also during this time, according to Schmidt, regimental founder and commanding officer Colonel Tilghman H. Good began sending multiple letters from his headquarters near Berryville, Virginia to his superiors in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, requesting promotions for additional members of the 47th Pennsylvania not only as a reward for the dedication and valor his men had repeatedly displayed in combat, but because of the planned departures by more than two hundred members of the regiment (the equivalent of more than two full companies) upon the 18 September 1864 expiration of their respective terms of service. Among those scheduled to depart were: Colonel Good and his second in command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, on 23-24 September, as well as these men from:

- Regimental Command: Regimental Surgeon and Assistant Surgeon, Elisha W. Baily, M.D. and Jacob H. Scheetz, M.D. (23 September 1864);

- Regimental Band: Bandmaster and A Company Private Anton B. Bush (via a surgeon’s certificate of disability), and Musician and G Company Private Frederick L. Jacobs;

- Company A: Captain Richard A. Graeffe, First Lieutenant James F. Meyers, Sergeant Bernard Brahler, Corporal Frederick Kageley, Private John Alder (teamster), and Privates Daniel Battaglia, William Borman, Samuel Danner, Lewis Gebhart, John Hawk, Joseph Kline, Mahlon and Owen Laub, Moritz Lazius, Peter Lewis, Frederick E. Meyers, Stephen I. Schmidt, Fred Sheniger, Andrew Thoman, Joseph A. Tice, Stephen Walter, and Charles Weidnecht;

- Company B: Captain Emanuel (E. P.) Rhoads, Second Lieutenant Allen G. Balliet, Private Henry A. Haltiman (who later re-enlisted with the regiment), Sergeant Oliver Hiskey, and Privates Henry Bergenstock, Alexander Blumer, Frederick Bohlen, Ephraim Clader, Edward Denhard, Peter Ferber, William Gangwere, Levi Knerr, Levi Martin, Luther Mennig, Casper Schreiner, Aaron Serfass, Charles W. Siegfeld, Charles Trexler, Christian Ungerer, William J. Weiss, Harrison and William Wieand, Abraham N. Wolf, and Franklin Young;

- Company C: Privates David S. Beidler, R. W. Druckemiller, Charles Harp, Conrad P. Holman, David W. and Isaac Kemble, George Miller, William Pfeil, William Plant, Alexander M. Ruffaner, Christian Schall, Isaac Snyder, Ephraim Thatcher, James and Samuel Whistler, Theodore Woodbridge, and Henry W. Wolf;

- Company D: Captain Henry Durant Woodruff, First Lieutenant Samuel S. Auchmuty, Sergeants Henry Heikel and Alexander David Wilson, Corporals Samuel A. M. Reed and Cornelius Baskins Stewart, and Privates George A. Berrier, Jacob Charles, William Collins, William Henry Coulter, George Washington Dill, George Washington Jury, Hugh O’Neil, George H. Rigler, William Sheaffer, William D. Stites, Wilson Tagg, and John Wantz;

- Company E: Captain Charles Hickman Yard, First Lieutenant Lawrence Bonstine, Second Lieutenant William H. Wyker, Sergeants Owen H. Weida and William R. Cahill, Corporal ThomasLowrey, Field Musician William Wilhelm (drummer boy), Privates John Bruch, Andrew Bucher, John Callahan, Jeremiah Cooper, Charles Dewey, John Dingler, William Ditterline, Henry Duffin, Adam P. Heckman, Samuel T. Hudson, Abraham Jacobus, William M. James, George W. Lantz, Henry Miller, Granville Moore, Richard Shelling, George W. Snyder, Joseph A. Tice, John Tidaboch, Theodore Troxell, and George Vogel;

- Company F: Captain Henry Samuel Harte, Sergeants William H. Glace, John W. Heberling, Albert H. McHose, Corporal James E. Patterson, Field Musician David Tombler, Privates David Andrews, Abraham Bander, Faustin Boyer, Augustus Eagle, Orlando Fuller, Joseph Geiger, Thomas B. Glick, John F. Haldeman, Joseph Heckman, Osman Houser, Henry Hummel, William Jordan, Owen Kern, George King, Nicholas Kuhn, William Kuntz, Joel Laudenschlager, Peter S. Levan, John Lucky, Albert J. Newhard, William Offhouse, Thomas B. Rhoads, Francis Roth, Llewellyn J. Schleppy, Gottlieb Schrum, Robert M. Sheats, Nicholas Smith, James Allen Trexler, John P. Weaver, and Gilbert Whiteman;

- Company G: First Sergeant D. K. Diefenderfer, Corporals Solomon Becker, Horatio Nelson Coffin, Reily M. Fornwald, William Hensler, and Allen Wolf, Field Musician William N. Smith, Privates Jacob H. Bowman, Lewis Dennis, Timothy Donahue, Ferdinand Fisher, Preston B. Good, Cornelius Heist, George T. Henry, Franklin Hoffert, Lewis Keiper, George Knauss, Orlando G. Miller, Barney Montague, George Reber, Francis Schmetzer, Frederick Weisbach, and Engelbert Zander;

- Company H: Captain James Kacy; Sergeants James F. Naylor, Robert H. Nelson and John P. Rupley, Corporal John Kitner, Field Musician Allen McCabe, Privates Augustus Bupp, John A. Durham, Thomas J. Haney, Isaac P. Henderson, Michael Horting, William C. Hutcheson, Adam, Louden, Walter C. Miller, Samuel M. Raudibaugh, David Thompson, Benjamin Thornton, and George W. Zinn;

- Company I: Second Lieutenant James Stuber, Corporals Francis S. Daeufer, John William Henry Diehl, Tilghman W. Fatzinger, Henry Miller and Daniel H. Nunnemacher, Privates Theodore Baker, Willoughby Fenstermaker, Allen P. Gilbert, Charles Gross, William F. Henry, Charles Kaucher, Edwin H. Keiper, Xaver Kraff, Ogdon Lewis, Peter Lynd, Aaron McHose, Gottlieb Schweitzer, William Smith, John L. Transue, John Troxell, Daniel Vansickle, Samuel W. Weirbach, Henry W. Wieser, and Nathaniel Xander; and

- Company K: Sergeants Peter Reinmiller and Conrad J. Volkenand, Corporals Lewis Benner, and George Knuck, Privates Valentine Amend, Martin Bornschier, Charles B. Fisher, Charles Heiney, Jacob Kingsley, John Koldhoff, Anthony Krauss, Samuel Madder, John Schimpf, John Scholl, and Christopher Ulrich.

Despite his expired term of service, Colonel Good remained in Virginia through September, helping to train and advise the replacement leaders of his regiment until finally opting in October 1864 to return home to the Keystone State. Meanwhile, as this loss of “institutional memory” from the Union was taking place, Confederate troops were on the move again. Per Shenandoah Valley Battlefields Foundation records:

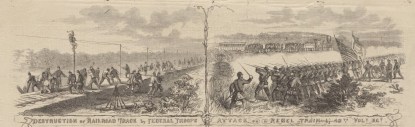

On September 15, Anderson left the Winchester area to return to Lee’s army and by the 18th had reached the Virginia Piedmont. Early spread out his remaining divisions from Winchester to Martinsburg, where he once more cut the B&O Railroad. When Sheridan learned of Anderson’s departure and the raid on Martinsburg, he determined to attack at once while the Confederate army was scattered….

By Saturday, 17 September 1864, Early had positioned his Confederate troops in a looming line from Winchester to Martinsburg, and the Opequon Creek was just two days away from becoming more than an obscure squiggly line on the future road maps of Virginia.

The Battle of Opequan* Begins

Major-General Philip Sheridan, U.S. Army (circa 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As rifles and cannon cooled following the Battle of Berryville, troops on both sides of the conflict tended to their wounded at the end of the first week of September 1864 while their respective commanding officers resumed their strategic planning. According to Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan:

Word to the effect that some of [Confederate Lieutenant-General] Early’s troops were under orders to return to Petersburg, and would start back at the first favorable opportunity, had been communicated to me already from many sources, but we had not been able to ascertain the date for their departure. Now that they had actually started, I decided to wait before offering battle until Kershaw had gone so far as to preclude his return, feeling confident that my prudence would be justified by the improved chances of victory; and then, besides, Mr. Stanton kept reminding me that positive success was necessary to counteract the political dissatisfaction existing in some of the Northern States. This course was advised and approved by General Grant, but even with his powerful backing it was difficult to resist the persistent pressure of those whose judgment, warped by their interests in the Baltimore and Ohio railroad, was often confused and misled by stories of scouts (sent out from Washington), averring that Kershaw and Fitzhugh Lee had returned to Petersburg, Breckenridge to southwestern Virginia, and at one time even maintaining that Early’s whole army was east of the Blue Ridge, and its commander himself at Gordonsville.

During the activity prevailing in my army … the infantry was quiet, with the exception of Getty’s division, which made a reconnaissance to the Opequon, and developed a heavy force of the enemy at Edwards’s Corners. The cavalry, however, was employed a good deal … skirmishing – heavily at times – to maintain a space about six miles in width between the hostile lines, for I wished to control this ground so that when I was released from the instructions of August 12 I could move my men into position for attack without the knowledge of Early….

It was the evening of the 16th of September that I received from Miss Wright* positive information that Kershaw was in march toward Front Royal on his way by Chester Gap to Richmond. Concluding that this was my opportunity, I at once resolved to throw my whole force into Newtown the next day, but a despatch [sic] from General Grant directing me to meet him at Charlestown … caused me to defer action until I should see him. In our resulting interview … I went over the situation very thoroughly, and pointed out with so much confidence the chances of a complete victory should I throw my army across the Valley pike near Newtown that he fell in with the plan at once, authorized me to renew the offensive, and to attack Early as soon as I deemed it most propitious to do so; and although before leaving City Point he had outlined certain operations for my army, yet he neither discussed nor disclosed his plans, my knowledge of the situation striking him as being so much more accurate than his own.

* Note: The Battle of Opequan is also often referred to as “Third Winchester” or the “Battle of Winchester.” Spelling variants of “Opequan” and “Opequon” are used throughout this article and the website for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story because battle reports penned by Union and Confederate commanders frequently presented the creek and battle name as “Opequan” while the spelling employed by the publishers of the various memoirs penned by Union Army leaders following the war was “Opequon.” (The spelling used by present-day Virginians is also “Opequon.”)

As the Battle of Opequan began, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was led by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, and attached to the U.S. Army’s 19th Corps commanded by Brigadier-General William H. Emory—as part of that corps’ 2nd Brigade, which was led by Brigadier-General James W. McMillan. This brigade also included the 12th Connecticut, 160th New York, and 8th Vermont volunteer armies.

Per his Personal Memoirs penned in 1888, former U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant recalled that, as General-in-Chief of the U.S. Army in 1864, he set off for Virginia on 15 September to offer guidance to Major-General Philip H. Sheridan:

My purpose was to have him attack Early, or drive him out of the valley and destroy that source of supplies for Lee’s army. I knew it was impossible for me to get orders through Washington to Sheridan to make a move, because they would be stopped there and such orders as Halleck’s caution (and that of the Secretary of War) … would be given instead, and would, no doubt, be contradictory to mine. I therefore, without stopping at Washington, went directly through to Charlestown, some ten miles above Harpers Ferry, and waited there to see General Sheridan, having sent a courier in advance to inform him where to meet me.

When Sheridan arrived I asked him if he had a map showing the positions of his army and that of the enemy. He at once drew one out of his side pocket, showing all roads and streams, and the camps of the two armies. He said that if he had permission he would move so and so (pointing out how) against the Confederates, and that he could ‘whip them.’ Before starting I had drawn up a plan of campaign for Sheridan, which I had brought with me; but, seeing that he was so clear and so positive in his views and so confident of success, I said nothing about this and did not take it out of my pocket.

Sheridan’s wagon trains were kept at Harper’s Ferry, where all of his stores were. By keeping the teams at that place, their forage did not have to be hauled to them. As supplies of ammunition, provisions and rations for the men were wanted, trains would be made up to deliver the stores to the commissaries and quartermasters encamped at Winchester. Knowing that he, in making preparations to move at a given day, would have to bring up wagon trains from Harpers’ Ferry, I asked him if he could be ready to get off by the following Tuesday. This was on Friday. ‘O yes,’ he said, he ‘could be off before daylight on Monday.’ I told him then to make the attack at that time and according to his own plan; and I immediately started to return to the army about Richmond. After visiting Baltimore and Burlington, New Jersey, I arrived at City Point on the 19th.

Regarding Sheridan’s aforementioned comments regarding “Miss Wright,” Rebecca McPherson Wright was a Quaker who taught at a private school in Winchester, Virginia during the early years of the Civil War. Described by Sheridan in his 1888 memoir as “faithful and loyal to the Government,” she risked her life to covertly provide accurate, critically important information to Union military leaders regarding the location, number and fitness of Confederate troops in the vicinity of Winchester, and was later rewarded with a position with the U.S. Treasury Department in recognition of her fidelity and valor.

Following his meeting with Grant, Sheridan returned to his headquarters in order to begin moving his troops “toward Newtown,” but halted those preparations upon notification that members of Early’s infantry were marching on Martinsburg:

This considerably altered the states of affairs, and I now decided to change my plan and attack at once the two divisions remaining about Winchester and Stephenson’s depot, and later, the two sent to Martinsburg; the disjointed state of the enemy giving me the opportunity to take him in detail, unless the Martinsburg column should be returned by forced marches.

While General Early was in the telegraph office at Martinsburg on the morning of the 18th, he learned of Grant’s visit to me; and anticipating activity by reason of this circumstance, he promptly proceeded to withdraw so as to get the two divisions within supporting distance of Ramseur’s, which lay across the Berryville pike about two miles east of Winchester, between Abraham’s Creek and Red Bud Run, so by the night of the 18th Wharton’s division, under Breckenridge, was at Stephenson’s depot, Rodes near there, and Gordon’s at Bunker Hill. At daylight of the 19th these positions of the Confederate infantry still obtained, with the cavalry of Lomax, Jackson, and Johnson on the right of Ramseur, while to the left and rear of the enemy’s general line was Fitzhugh Lee, covering from Stephenson’s depot west across the Valley pike to Apple-pie Ridge.

Opequon Crossing, circa 1930s (courtesy of Southern Methodist University).

The Opequon Creek “flow[ed] at the foot of a broad and thickly wooded gorge, with high and steep banks” during September of 1864, according to historian Richard B. Irwin. Travelers along the roughly three-mile route to Winchester on the Berryville Road would move from ravine “to the level of rolling plain,” encountering “high ground … covered with large oaks, pines and undergrowth,” which was “intersected by many brooks,” the largest of which was the Red Bud Run, and “a still larger stream, called Abraham’s Creek,” which “after pursuing a nearly parallel course on the south side of the defile, crosses the road not far from the ford” before emptying into the Opequon.

The Union cavalry had maintained control of the six miles east of the Opequan, and at 2 AM Monday, the 19th, Sheridan set his forces in motion. The route was through Berryville, across the Opequan and on to Winchester. The 6th Corps led off, followed by its wagon train, then the 19th Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania], and finally the Army of West Virginia bringing up the rear. Unfortunately, east of the Opequan, the 6th and 19th Corps became entangled, and the 19th Corps halted to let the 6th Corps pass, hopelessly stringing out the Union troops which were separated by the wagon train. Eventually the 19th Corps moved into the woods on either side of the road and managed to get by the train, but it took six hours to travel the 3 miles in crossing the Opequan, and form a line of battle between the creek and Winchester at 11:40 a.m. This same confusion along the route of the march, caused the artillery to be delayed. As a result, the Confederate forces of Gen. Early had time to reach and consolidate in preparation for the impending engagement.

Sheridan, recalled a later departure time, noting:

My army moved at 3 o’clock that morning. The plan was for Torbert to advance with Merritt’s division of cavalry from Summit Point, carry the crossings of the Opequon at Stevens’s and Lock’s fords, and form a junction near Stephenson’s depot, with Averell, who was to move south from Darksville by the Valley pike. Meanwhile, Wilson was to strike up the Berryville pike, carry the Berryville crossing of the Opequon, charge through the gorge or cañon on the road west of the stream, and occupy the open ground at the head of this defile. Wilson’s attack was to be supported by the Sixth and Nineteenth corps, which were ordered to the Berryville crossing, and as the cavalry gained the open ground beyond the open gorge, the two infantry corps, under command of General Wright, were expected to press on after and occupy Wilson’s ground, who was then to shift to the south bank of Abraham’s creek and cover my left; Crook’s two divisions, having to march from Summit Point, were to follow the Sixth and Nineteenth corps to the Opequon, and should they arrive before the action began, they were to be held in reserve till the proper moment came, and then, as a turning-column, be thrown over toward the Valley pike, south of Winchester.”

Battle of Opequan (aka Third Winchester), Virginia, 19 September 1864 (public domain).

By dawn on 19 September, the brigade from Wilson’s division headed by McIntosh had succeeded in compelling Confederate pickets to flee their Berryville positions with “Wilson following rapidly through the gorge with the rest of the division, debouched from its western extremity with such suddenness as to capture as to capture a small earthwork in front of General Ramseur’s main line.” Although “the Confederate infantry, on recovering from its astonishment, tried hard to dislodge them,” they were unable to do so, according to Sheridan. Wilson’s Union troops were then reinforced by the U.S. 6th Army.

I followed Wilson to select the ground on which to form the infantry. The Sixth Corps began to arrive about 8 o’clock, and taking up the line Wilson had been holding, just beyond the head of the narrow ravine, the cavalry was transferred to the south side of Abraham’s Creek.

The Confederate line lay along some elevated ground about two miles east of Winchester, and extended from Abraham’s Creek north across the Berryville pike, the left being hidden in the heavy timber on Red Bud Run. Between this line and mine, especially on my right, clumps of woods and patches of underbrush occurred here and there, but the undulating ground consisted mainly of open fields, many of which were covered with standing corn that had already ripened.

“The 6th Corps formed across the Berryville Road” while the “19th Corps prolonged the line to the Red Bud on the right with the troops of the Second Division.” According to Irwin, the:

First Division’s First and Second Brigades, under Beal and McMillan, formed in the rear of the Second Division and on the right flank. Beal’s First Brigade was on the right of the division’s position, and McMillan’s Second Brigade deployed on the left and rear of Beal; in order of the 47th Pennsylvania, 8th Vermont, 160th New York, and 12th Connecticut, with five companies of the 47th Pennsylvania deployed to cover the whole right flank of his brigade and to move forward with it by the flank left in front. By this time, the Army of West Virginia had crossed the ford and was massed on the left of the west bank.

While the ground in front of the 6th Corps was for the most part open, the 19th Corps found itself in a dense wood, restricting its vision of both the enemy and its own forces.

“Much time was lost in getting all of the Sixth and Nineteenth corps through the narrow defile,” Sheridan observed, adding that, because Grover’s division was “greatly delayed there by a train of ammunition wagons … it was not until late in the forenoon that the troops intended for the attack could be got into line ready to advance.” As a result:

General Early was not slow to avail himself of the advantages thus offered him, and my chances of striking him in detail were growing less every moment, for Gordon and Rodes were hurrying their divisions from Stephenson’s depot across-country on a line that would place Gordon in the woods south of Red Bud Run, and bring Rodes into the interval between Gordon and Ramseur.

When the two corps had all got through the cañon they were formed with Getty’s division of the Sixth to the left of the Berryville pike, Rickett’s division to the right of the pike, and Russell’s division in reserve in rear of the other two. Grover’s division of the Nineteenth Corps came next on the right of Rickett’s, with Dwight to its rear in reserve, while Crook was to begin massing near the Opequon crossing about the time Wright and Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] were ready to attack.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

More than a quarter of a century after the clash, Irwin conjured the spirit of the battle’s beginning:

About a quarter before twelve o’clock, at the sound of Sheridan’s bugle, repeated from corps, division, and brigade headquarters, the whole line moved forward with great spirit, and instantly became engaged. Wilson pushed back Lomax, Wright drove in Ramseur, while Emory, advancing his infantry [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] rapidly through the wood, where he was unable to use his artillery, attacked Gordon with great vigor. Birge, charging with bayonets fixed, fell upon the brigade of Evans, forming the extreme left of Gordon, and without a halt drove it in confusion through the wood and across the open ground beyond to the support of Braxton’s artillery, posted by Gordon to secure his flank on the Red Bud road. In this brilliant charge, led by Birge in person, his lines naturally became disordered….

Sharpe, advancing simultaneously on Birge’s left, tried in vain to keep the alignment with Ricketts and with Birge…. At first the order of battle formed a right angle with the road, but the bend once reached, in the effort to keep closed upon it, at every step Ricketts was taking ground more and more to the left, while the point of direction for Birge, and equally for Sharpe, was the enemy in their front, standing almost in the exact prolongation of the defile, from which line, still plainly marked by Ash Hollow, the road … was steadily diverging.

As the battle continued to unfold, the disorganization affected the lines on both sides of the conflict. According to Irwin:

The 19th Corps Second Division was initially successful, but in its charge became disorganized; and the troops on the left in following the less obstructed area of the road which veared [sic] slightly left, soon opened up a gap on their right; while the remainder of the Union forces were moving straight ahead as they engaged the Confederates. This gap eventually reached 400 yards in width, an opportunity the Confederates soon exploited. Fortunately the Confederates were soon themselves disorganized by their advance, and encountering fresh Union troops on their right flank were halted. The Confederate attack on the right flank also achieved initial success, until halted by Beal’s first brigade.

McMillan had been ordered to move forward at the same time as Beal, and to form on his left. The five companies of the 47th Pennsylvania that had been detached to form a skirmish line on the Red Bud Run to cover McMillan’s right flank, had some how [sic] lost their way on the broken ground among the thickets, and, not finding them in place, McMillan had been obliged to send the remaining companies of the same regiment to do the same duty, and brought the rest of the brigade to the front to restore the line. The line then charged and drove the Confederates back beyond the positions where their attack had started. The initial engagement had lasted barely an hour, and by 1 PM was over. The right flank of the 19th Corps was held by the 47th Pennsylvania and 30th Massachusetts.

According to Sheridan:

Just before noon the line of Getty, Ricketts, and Grover moved forward, and as we advanced, the Confederates, covered by some heavy woods on their right, slight underbrush and corn-fields along their centre [sic], and a large body of timber on their left along the Red Bud, opened fire from their whole front. We gained considerable ground at first, especially on our left but the desperate resistance which the right met with demonstrated that the time we had unavoidably lost in the morning had been of incalculable value to Early, for it was evident that he had been enabled already to so far concentrate his troops as to have the different divisions of his army in a connected line of battle in good shape to resist.

Getty and Ricketts made some progress toward Winchester in connection with Wilson’s cavalry…. Grover in a few minutes broke up Evans’s brigade of Gordon’s division, but his pursuit of Evans destroyed the continuity of my general line, and increased an interval that had already been made by the deflection of Ricketts to the left, in obedience to instructions that had been given him to guide his division on the Berryville pike. As the line pressed forward, Ricketts observed this widening interval and endeavored to fill it with the small brigade of Colonel Keifer, but at this juncture both Gordon and Rodes struck the weak spot where the right of the Sixth Corps and the left of the Nineteenth should have been in conjunction, and succeeded in checking my advance by driving back a part of Ricketts’s division, and the most of Grover’s. As these troops were retiring I ordered Russell’s reserve division to be put into action, and just as the flank of the enemy’s troops in pursuit of Grover was presented, Upton’s brigade, led in person by both Russell and Upton, struck it in a charge so vigorous as to drive the Confederates back … to their original ground.

The success of Russell enabled me to re-establish the right of my line some little distance in advance of the position from which it started in the early morning, and behind Russell’s division (now commanded by Upton) the broken regiments of Ricketts’s division were rallied. Dwight’s division was then brought up on the right, and Grover’s men formed behind it….

No news of Torbert’s progress came … so … I directed Crook to take post on the right of the Nineteenth Corps and, when the action was renewed, to push his command forward as a turning-column in conjunction with Emory. After some delay … Crook got his men up, and posting Colonel Thoburn’s division on the prolongation of the Nineteenth Corps, he formed Colonel Duval’s division to the right of Thoburn. Here I joined Crook, informing him that … Torbert was driving the enemy in confusion along the Martinsburg pike toward Winchester; at the same time I directed him to attack the moment all of Duval’s men were in line. Wright was introduced to advance in concert with Crook, by swinging Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania and his other 19th Corps’ troops] and the right of the Sixth Corps to the left together in a half-wheel. Then leaving Crook, I rode along the Sixth and Nineteenth corps, the open ground over which they were passing affording a rare opportunity to witness the precision with which the attack was taken up from right to left. Crook’s success began the moment he started to turn the enemy’s left…

Both Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and Wright took up the fight as ordered…. [A]s I reached the Nineteenth Corps the enemy was contesting the ground in its front with great obstinacy; but Emory’s dogged persistence was at length rewarded with success, just as Crook’s command emerged from the morass of the Red Bud Run, and swept around Gordon, toward the right of Breckenridge….”

As “Early tried hard to stem the tide” of the multi-pronged Union assault, “Torbert’s cavalry began passing around his left flank, and as Crook, Emory, and Wright attacked in front, panic took possession of the enemy, his troops, now fugitives and stragglers, seeking escape into and through Winchester,” according to Sheridan.

When this second break occurred, the Sixth and Nineteenth corps were moved over toward the Millwood pike to help Wilson on the left, but the day was so far spent that they could render him no assistance.” The battle winding down, Sheridan headed for Winchester to begin writing his report to Grant.

According to Irwin, although the heat of battle had cooled by 1 p.m., troop movements had continued on both sides throughout the afternoon until “Crook, with a sudden … effective half-wheel to the left, fell vigorously upon Gordon, and Torbert coming on with great impetuosity … the weight was heavier than the attenuated lines of Breckinridge and Gordon Could bear.” As a result, “Early saw his whole left wing give back in disorder, and as Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] and Wright pressed hard, Rodes and Ramseur gave way, and the battle was over.”

Early vainly endeavored to reconstruct his shattered lines [near Winchester]. About five o’clock Torbert and Crook, fairly at right angles to the first line of battle, covered Winchester on the north from the rocky ledges that lie to the eastward of the town…. Thence Wright extended the line at right angles with Crook and parallel with the valley road, while Sheridan drew out Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] … and sent him to extend Wright’s line to the south….

Sheridan, mindful that his men had been on their feet since two o’clock in the morning … made no attempt to send his infantry after the flying enemy….

Sheridan … openly rejoiced, and catching the enthusiasm of their leader, his men went wild with excitement when, accompanied by his corps commanders, Wright and Emory and Crook, Sheridan rode down the front of his lines. Then went up a mighty cheer that gave new life to the wounded and consoled the last moments of the dying….

When the President heard the news his first act was to write with his own hand a warm message of congratulation, and this he followed up by making Sheridan a brigadier-general in the regular army, and assigning him permanently to the high command he had been exercising under temporary orders.

Summing up the battle for Lincoln and Grant, Sheridan reported:

My losses in the Battle of Opequon were heavy, amounting to about 4,500 killed, wounded and missing. Among the killed was General Russell, commanding a division, and the wounded included Generals Upton, McIntosh and Chapman, and Colonels Duval and Sharpe. The Confederate loss in killed, wounded, and prisoners equaled about mine. General Rodes being of the killed, while Generals Fitzhugh Lee and York were severely wounded.

We captured five pieces of artillery and nine battle flags. The restoration of the lower valley – from the Potomac to Strasburg – to the control of the Union forces caused great rejoicing in the North, and relieved the Administration from further solicitude for the safety of the Maryland and Pennsylvania borders. The President’s appreciation of the victory was expressed in a despatch [sic] so like Mr. Lincoln I give a fac-simile [sic] of it to the reader. This he supplemented by promoting me to the grade of brigadier-general in the regular army, and assigning me to the permanent command of the Middle Military Department, and following that came warm congratulations from Mr. Stanton and from Generals Grant, Sherman and Meade.

“The losses of the Army of the Shenandoah, according to the revised statements compiled in the War Department, were 5018, including 697 killed, 3983 wounded, 338 missing,” per revised estimates by Irwin. “Of the three infantry corps, the 19th, though in numbers smaller than the 6th, suffered the heaviest loss, the aggregate being 2074 [314 killed, 1554 wounded, 206 missing]. Conversely, Early “lost nearly 4000 in all, including about 200 prisoners; or as other sources reported, anywhere from 5500 to 6850 killed, wounded, and missing or captured.”

Despite the significant number of killed, wounded and missing on both sides of the conflict, casualties within the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were surprisingly low. Private Thomas Steffen of Company B was killed in action while F Company Private William H. Jackson’s cause of death was somewhat less clear; he was reported in Bates’ History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5 as having died on the same day on which the battle took place.

Among the wounded were C Company Corporal Timothy Matthias Snyder, who was wounded slightly in the knee, and Privates William Adams (E Company), Charles Pfeiffer (B Company), who lost the forefinger of his right hand, J. D. Raubenold (B Company), and Edward Smith (E Company).

As he penned his memoir in 1885 during the final days of his life, President Ulysses S. Grant again made clear the significance of the Battle of Opequan:

Sheridan moved at the time he had fixed upon. He met Early at the crossing of Opequon Creek [September 19], and won a most decisive victory – one which electrified the country. Early had invited this attack himself by his bad generalship and made the victory easy. He had sent G. T. Anderson’s division east of the Blue Ridge [to Lee] before I [Grant] went to Harpers Ferry and about the time I arrived there he started with two other divisions (leaving but two in their camps) to march to Martinsburg for the purpose of destroying the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad at that point. Early here learned that I had been with Sheridan and, supposing there was some movement on foot, started back as soon as he got the information. But his forces were separated and … he was very badly defeated. He fell back to Fisher’s Hill, Sheridan following.

Battle of Winchester, 19 September 1864 (Harper’s Weekly, 8 October 1864, public domain). Also known as the “Battle of Opequan” or “Third Winchester.”

In its 8 October 1864 edition, Harper’s Weekly recapped the battle as follows:

The engraving on page 644 illustrates one of the most spirited actions, and certainly the most imposing spectacle of the war. It will be remembered that Sheridan, after having got the Sixth Corps across the Opequan, was compelled to wait full two hours for the arrival of the Nineteenth, and as a consequence of this to form an entirely new plan of battle in the face of an enemy already prepared and in line. At first the advantage appeared to rest with Early, whose fierce cannonade broke Sheridan’s first line, and threatened to disturb his second. But this state of affairs changed as soon as the Federal artillery got in position. The line of battle was reformed, and the conflict opened in terrible earnest. The two opposing armies were are some points not more than two hundred yards apart. The slaughter is described to have been truly awful; but the advantage rested now with Sheridan’s advancing columns. At a critical point in the fight the cavalry bugle was heard above the din of the strife and the shouts of the contending armies; then followed the charge, led by such soldiers as Merritt and Custer and Torbert, upon the enemy’s right. This decided the fortunes of the day. The movement was in accordance with Sheridan’s deep laid plan, and besides being the most magnificent of spectacles was also a most wonderful success. ‘The stubborn columns of Early’s command,’ says the Tribune correspondent, ‘were forced to give way, and break before the fierce onslaught which our cavalry made upon them, who, with sabre in hand, rode them down, cutting them right and left, capturing 721 privates and non-commissioned officers, with nine battle-flags and two guns.’ Thus was fought and won the battle of Winchester, September 19, 1864. [Also known as the Battle of Opequan.]

Outcome and Immediate Aftermath of the Battle of Opequan (Third Winchester)

According to historian Richard Bluhm, during the “severe fighting” in and around the Opequon Creek on 19 September, the Union’s:

VI Corps troops pushed Ramseur and Rodes back while XIX Corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers] attacked Gordon’s position on the rebel left. As the two Union corps advanced, a gap opened between them. Two Confederate brigades charged into it and threatened to collapse the entire Union right until a counterattack by Russell’s division restored the Union line. Meanwhile, Sheridan, concerned how Torbert was faring at Stephenson’s Depot, redirected Crook to move his command to the Union right, toward Gordon’s rebel lines. North of Winchester, Wharton’s [Confederate] infantry temporarily held its position until Averell’s [Union] cavalry outflanked it, forcing the rebels back. Breckinridge [and his Confederate troops] retired toward Winchester with the Union cavalry in pursuit, but, near the town, Wharton’s two brigades counterattacked and stalled Torbert’s [Union] advance.

About the same time, Sheridan ordered a final coordinated thrust against the Confederate line, which was now bent into an L-shaped formation to the north and east of Winchester. Crook’s [Union] troops hit Gordon’s left flank and turned into it, sending the Confederate division reeling back, while Wright and Emory also brought their corps [including the 47th Pennsylvania] into action. Merritt’s and Averell’s Federal divisions made a classic cavalry charge into the Confederates’ far left flank, breaking the infantry lines. The combination of assaults shattered Early’s [Confederate] position and forced his army south in an orderly retreat out of Winchester. Sheridan’s [Union] infantry stopped on the south edge of the town while Union cavalry continued to pursue the Confederates to Kernstown. Early ended his retreat at a strong position on Fisher’s Hill about twenty miles away.

Sheridan continued his offensive against Early the next day At dawn, 20 September, his army moved south toward Fisher’s Hill. Crook received orders to make a concealed march the next day to hidden positions west of Fisher’s Hill and then make an assault on 22 September. Meanwhile, Sheridan sent Torbert east around Massanutten Mountain into the Luray Valley with a reinforced cavalry division. He was to cross back into the Valley some thirty miles south at New Market to cut off Early’s retreat.

Convinced that Early was finally beaten, Grant wanted Sheridan to move against the rail junction at Charlottesville, but Sheridan balked. He was almost one hundred miles from the closest Union supply depot, and foraging efforts in the picked over Valley could not support his army. He suggested destroying crops, barns, and other supplies in the Shenandoah Valley and then withdrawing with his army northward. With Grant’s approval, Sheridan sent Union cavalry as far south as Waynesboro to cut the railroads, burn grain and woolen mills, and seize or destroy crops and livestock….

The Battle of Fisher’s Hill

Fisher’s Hill, Virginia, circa 1892 (William Henry Jackson, Detroit Publishing Co., U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Per Irwin, the military value of Fisher’s Hill, Virginia “resided mainly in the fact that between the peaks of Masanutten and the North Mountains the jaws of the valley were contracted to a width of not more than four miles.

The right flank of this shortened front rests securely upon the north fork of the Shenandoah, where it winds about the base of Three Top Mountain before bending widely toward the east to join the south fork and form the Shenandoah River. Across the front, among rocks, between steep and broken cliffs, winds the brawling brook called Tumbling Run, and above it, from its southern edge, rises the rugged crag called Fisher’s Hill.”

“Forward the Skirmishers: On the Advance to Fisher’s Hill” (Alfred Waud, 22 September 1864, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

It was in and around this high ground that Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early chose to regroup following his defeat on 19 September 1864 during the Battle of Opequan. But Sheridan and his Union troops were not about to let that happen. According to Irwin:

On the morning of the 20th of September Sheridan set out to follow Early, and in the afternoon took up a position before Strasburg, the Sixth Corps on the right, Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] on the left, and Crook behind Cedar Creek in support. The next morning the 21st, Sheridan pushed and followed Early’s skirmishers over the high hill that stands between Strasburg and Fisher’s Hill, overlooking both, drove them behind the defences [sic] of Fisher’s Hill, and took up a position covering the front from the banks of the North Fork on the left, where Emory’s left rested lightly, to the crown of the hill just mentioned, which commanded the approach by what is called the back road, or Cedar Creek grade, and was but slightly commanded by Fisher’s Hill itself. This strong vantage-ground Wright wrested from the enemy after a struggle, and felling the trees for protection and for range, planted his batteries there. The ground was very difficult, broken and rocky, and to hold it the Sixth Corps had to be drawn toward the right, while Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania], following the movement, in the dark hours of the early morning of the 22d of September, extended his front so as to cover the ground thus given up by Wright.

Sheridan now thought of nothing short of the capture of Early’s army. Torbert was to drive the Confederate cavalry through the Luray, and thence, crossing the Massanutten range, was to lay hold of the valley pike at New Market, and plant himself firmly in Early’s rear on his only line of retreat. Crook, by a wide sweep to the right, his march hidden by the hills and woods, was to gain the back road, so as to come up secretly on Early’s left flank and rear, and the first sounds of battle … were to serve as a signal for Wright and Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] to fall on with everything they had.

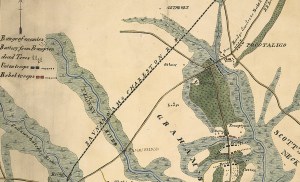

Battlefields of Fisher’s Hill and Cedar Creek, Virginia (U.S. Engineers’ Map, Lt.-Col. G. L. Gillespie, 1873, public domain).

During the forenoon of the 22d, Grover held the left of the position of the Nineteenth Corps, his division formed in two lines in the order of Macauley, Birge; Shunk, Molineaux. Dwight, in the order of Beal, McMillan [including the 47th Pennsylvania], held the right, and connected with Wheaton. In taking ground toward the right … this line had become too extended, and, as it was necessary that the left of the skirmishers, at least, should rest upon the river, Grover shortened his front by moving forward Foster with the 128th and Lewis with the 176th New York to drive in the enemy’s skirmishers opposite, and to occupy the ground that they had been holding. This was handsomely done under cover of a brisk shelling from Taft’s and Bradbury’s guns. As on the rest of the line, the whole front of the corps was covered as usual by hasty entrenchments. In the afternoon Ricketts moved far to the right, and seized a wooded knoll commanding Ramseur’s position on Fisher’s Hill. In preparation for the attack Sheridan gave Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] the ground on the left of the railway, and Wright that beyond it, and Molineaux moved forward to lead the advance of Grover. The sun was low when the noise of battle was heard far away on the right. This was Crook, sweeping everything before him as he charged suddenly out of the forest full upon the left flank and rear of Lomax and Ramseur, taking the whole Confederate line completely in reverse. The surprise was absolute. Instantly Wright and Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] took up the movement, and, inspired by the presence and the impetuous commands of Sheridan, descended rapidly the steep and broken sides of the ravine, at the bottom of which lies Tumbling Run, and then rather scrambling than charging up the rocky and almost inaccessible sides of Fisher’s Hill, swarmed over the strong entrenchments, line after line, and planting their colors upon the parapets, saw the whole army of Early in disorderly flight. Foremost to mount the parapet was Entwistle with his company of the 176th New York…. Crook, but almost at the same instant Wilson, gallantly leading the 28th Iowa, planted the colors of his regiment in the works…. [T]he Confederates … abandoned sixteen pieces of artillery where they stood. Early was unable to arrest the retreat of his army until he found himself near Edenburg, four miles beyond Woodstock.

Sheridan’s loss in this battle was 52 killed, 457 wounded, 19 missing, in all, 528…. Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania] accounts for 15 killed, 86 wounded, 13 missing, together 114…. Early reports his loss in the infantry and artillery alone as 30 killed, 210 wounded, 995 missing, total 1,235; but Sheridan claims 1,100 prisoners….

[Sheridan] without a halt … pushed forward his whole organization, each regiment or brigade nearly in the order in which it chanced to file into the road. Devin’s cavalry brigade trod closely on the heels of what was left of Lomax, and Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania], whose line had crossed the valley road, pushed up it as fast as the men could move over the ground. Wright moved in close support of Emory and personally directed the operations of both corps, the Nineteenth as well as the Sixth. So fast did the infantry march that it was 10 o’clock at night before Devin, from his place in line on the right of the Sixth Corps, was able to take the road abreast with the Nineteenth, and broad daylight before his or any other horsemen passed the hardy yet toil-worn soldiers of Molineaux, who were left all night to lead the swift pursuit…. About half-past eight the head of the column first came in contact with the rear-guard of the enemy, but this was soon driven in, and no further resistance was offered until about an hour later, at the crossing of a creek near Woodstock, a brisk fire of musketry, aided by two guns in the road, was opened on Molineaux’s front, but was quickly silenced. At dawn on the 23d of September Sheridan went into bivouac covering Woodstock, and let the infantry rest until early in the afternoon, when he again took up the pursuit with Wright and Emory [including the 47th Pennsylvania], leaving Crook to care for the dead and wounded. Early fell back to Mount Jackson, and was preparing to make a stand when Averell coming up, he and Devin made so vigorous a demonstration with the cavalry alone that Early thought it best to continue his retreat beyond the North Fork to Rude’s Hill, which stands between Mount Jackson and New Market.

Sheridan advanced to Mount Jackson on the morning of the 24th of September, and before nightfall had concentrated his whole army there. He was moving his cavalry to envelop both of Early’s flanks and the infantry, Wright leading, to attack in front. However, Early did not wait for this, but retreated rapidly in order of battle, pursued by Sheridan in the same order, that is by the right of the regiments with an attempt at deploying intervals through New Market and six miles beyond to a point where a country road diverges through Keezletown and Cross Keys to Port Republic, at the head of the South Fork. Here both armies halted face to face, Sheridan for the night; but Early, as soon as it was fairly dark, fell back about five miles on the Port Republic road, and again halted at a point about fourteen miles short of that town.

Early’s object in quitting the main valley road, which would have conducted him to Harrisonburg, covering Staunton, was to receive once more the reinforcements that Lee, at the first tidings from Winchester, had again hurried forward under Kershaw. On the 25th of September, therefore, Early retreated through Port Republic toward Brown’s Gap, where Kershaw, marching from Culpeper through Swift Run Gap, joined him on the 26th. Here also Early’s cavalry rejoined him, Wickham from the Luray valley, and Lomax, pressed by Powell, from Harrisonburg.