Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, view from the sea, 1946 (Vacation photograph collection of President Harry Truman, November 1946, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

Still stationed at Fort Jefferson in Florida’s Dry Tortugas in July 1863, Lieutenant-Colonel George W. Alexander and the members of Companies F, H and K baked in the unrelenting heat while on duty and sought refuge in the cooler spaces of the fort and island when not. The inferior quality of water available to them continued to wreak havoc on their health. That month alone, twenty-three members of the regiment and twenty-six of the prisoners they were guarding were admitted to the fort’s post hospital with a range of ailments, including six cases of fever (five bilious remittent and one intermittent), seven with intestinal-related diseases (four with dysentery, two with chronic diarrhea, and one with hemorrhoids/piles that were likely caused by the prior two conditions), and three with inflammatory diseases or infections (boils or carbuncles, funiculitis, odontalgia (toothache), orchitis, otitis (earache), along with assorted injuries, including abrasions, sprains and hernia issues.

Meanwhile, the members of Companies A, B, C, D, E, G, and I were still stationed at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida, under the command of the regiment’s founder, Colonel Tilghman H. Good. They too waged their own battles with the heat and disease.

* Note: The members of Company D had just returned to Fort Taylor from Fort Jefferson in mid-May 1863.

Taking time to record his thoughts in his diary throughout July, Private Henry J. Hornbeck of Company G noted that he was “busy in office” during the first two days of the month as he “procured Henry Kramer Company B as cook for our mess” on 1 July and as the “U.S. Gunboat Bermuda arrived from New Orleans,” that same afternoon, “having an old mail for this place, which had passed here, and had gone on there, some time ago…. Weiss & myself took a short walk towards the barracks, accompanying Pretz & Lawall. After which returned to office…. Ginkinger, Whiting & myself then went in bathing off the wharf. Retired at 11 p.m.”

On July 3, he noted, “Could not sleep tonight on account of the heat, sitting up greater portion of the night.”

First Lieutenant George W. Huntsberger, Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, circa 1863 (public domain).

The year was also proving to be an unforgettable one for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry in an entirely different way—many of the carte de visite images taken of its members were taken in 1863, according to historian Lewis Schmidt, who has stated that the photographer of choice for the regiment’s officers was Moffat & Simpson on Duval Street in Key West.

Members of the regiment who were still serving at Fort Taylor during this time commemorated the Fourth of July in grand style as “the celebrations began at Key West at 9 AM,” according to Schmidt. Following an inspection and review of the five companies stationed at the fort by Brigadier-General Woodbury, “the regiment marched in a ‘street parade through the principal streets of the city in heat of 110 degrees Fahrenheit and the dust almost suffocating’. After which ‘each detachment was taken to their quarters, dismissed, and then to enjoy themselves as best they could… Col. Good fired the National Salute of 35 guns from Fort Taylor at Meridian [noon]…. There was a great amount of firing from the vessels in the harbor in honor of the day.’”

According to Private Hornbeck, his holiday was only partially duty free with “No work in office.” But he still had an early start to what became a very long, but memorable Fourth.

Rose at 4 a.m. went with Ginkinger to Slaughter House, procured rations of fresh beef for our mess. Mennig & Myself went to fish market, purchased two fish. Took a cup of coffee at café opposite Provost Marshals Office. After breakfast Whiting & myself played a game of billiards, then witnessed the parade of 47th P. V. 5 Companies with Band & Col. & Staff. Review by the Genl. At Headquarters. Dispersed at 11 a.m. Weather extremely hot. Provost Guard quarters finely decorated. Flags hoisted at great many places. Firing squibs &c, salute by Fort Taylor & Gunboats in harbor, as usual on such occasions. Remained in office all day. After supper Ginkinger & myself visited Capt. Bell, then went with Serg’t. Mink to procure ice cream at a Colored Woman’s establishment, after which returned to office. Many of boys, as usual upon such occasions, being today pretty well curried. Today the San Jacinto relieved the Magnolia as Flag Ship for this port. After taking a sea bath retired at 11 p.m.

From the perspective of C Company Musician Henry D. Wharton:

The city was gaily dressed in flags, and the prettiest thing of the kind was that at the guard station, under Lt. Reese of Company C. Five flags were suspended from the quarters, with wreaths, while the whole front of the enclosure of the yard was covered with evergreens and the red, white, and blue. The Navy had their vessels dressed in their best ‘bib and tucker’, flags flying fore and aft, of our own and those of all nations. It was a pretty sight, and in a measure paid for the fatigue of the boys on their march. At 12 noon, both Army and Navy fired a national salute of thirty five guns.

A day later, Private Hornbeck noted “News very bad. Lee’s army still in Pennsylvania making bad havoc,” and on July 7, “Weather sultry & mosquitoes again at work.” During this time, he was also hard at work updating the regiment’s commissary paperwork to enable the commissary staff to issue rations to members of the regiment later that week. On July 9, he recorded the following:

Busy today, moving the office next door to Provost Marshal’s office, fine place. Tug Reaney returned from Havana having a mail…. News very bad from Pa. Rebels about to attack Harrisburg. The Militia confident of holding the place. Bridges &c burnt on the Susquehanna…. Steamer Creole passed by this evening Pilot Boat brought in a paper up to July 3 reports 9000 Rebels to be Captured between Carlisle & Chambersburg. Genl. Hooker relieved from Command of Army of Potomac and Genl. Meade his successor, general satisfaction by this change…. Weather cool this evening.

Around this same time, Major William Gausler, who had been appointed by senior Union Army leaders to serve as the provost marshal of Key West, described the influence that the 47th Pennsylvania’s presence was having on local residents, noting “morals of the city in a good state,” and ascribing at least part of that success to C Company’s First Lieutenant William Reese:

The days are quiet, but the nights are a busy time for Lt. Reese at the guard station…. Woe betide those who imbibe sufficient to make them weak in the knees, for a soft plank in the lockup will be their bed, and a fine in the morning…. Reese is playing the deuce [with local residents selling liquor illegally] in the way of confiscating the ardent-stuff, sure to kill at forty yards. A few days ago he captured ‘eleven five gallon demijohns under the floor of a house, and another in a barrel covered with flowers in the lower part of the yard, where the [local resident] had been selling it to the sailors and soldiers in bottles containing scarcely a pint, at the exorbitant price of three dollars a bottle. A nice profit, as the stuff costs fifty five cents per gallon, clear of duties, being smuggled in at night.’”

That bootlegger was fined $400, according to Schmidt.

Captain Henry Durant Woodruff, commanding officer of Company D, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (public domain).

Also according to Schmidt, additional festivities ensued on July 16, 1863 when members of Company D “presented a magnificent sword, sash, and belt” to Captain Woodruff “at the US Barracks in Key West.”

The company was formed in front of their quarters at 8 AM, across the barracks ground from Company C, and Pvt. George W. Baltozer, a 24 year old teacher from Perry County, made the following remarks on behalf of the company:

‘The motives that assemble us on the present occasion are based on our mature confidence, the martial skill, the intrepid heroism, and the undaunted intrepidity of our leader in arms. It is manifestive of our consciousness of your noble ability to wield in the defence [sic] of the rights of our country, this glittering weapon, that we place it in your protective hand. Receive it, sir, as a token of our estimation of your promotion of our ease and comfort in quietude, and for your chivalrous spirit on the sanguine field, when the heavens glared with fire, and the earth trembled ‘neath cannons’ roar. May it never rest in its scabbard ’till rebellion is crushed and traitorism is banished from the land, and peace spread her white wings from the St. John’s to the sunny banks of the Rio Grande. May it ever bespeak in the heart of him that wields it, bravery, loyalty, heroism, and philanthropy. That it may ever benefit you in the hour of peril, and that you may undauntingly use it as opportunity is afforded, is the very ardent wish of your most obedient servants.'”

Captain Woodruff then responded to this touching tribute by presenting a surprisingly lengthy address to his men:

My companions in arms, your beautiful present is accepted with sincere satisfaction and heartfelt thanks. It affords the satisfaction that you still respect and have confidence in your commander, and he is thankful not only for the value of this noble gift, but for the rich token of your kind regard. And while I wear these arms and accoutrements, emblematical of my rank and office, may they never be worn unworthily, or the noble donors have cause to blush for the ungallant act of the wearer.

Two years have nearly elapsed since we have been associated as commander and commanded. Two years of privation and toil, yet your love for the cause and your ardor to serve your country has not abated.

When you entered upon this gigantic struggle, you were not prompted by large bribes or bounties, or intimidated by being forced in service by conscription. But inspired by a noble patriotism, you cheerfully volunteered for the longest period known to law.

Your conduct thus far has been in accordance with the honorable principles which caused you to volunteer. No discipline too strict, no privations too great, no toil too sore, but that your indomitable spirits have been able to accomplish, to undergo and overcome. And now allow me to say to you that I am proud of the noble men who compose this company; I am proud of your generous and gallant conduct; I am proud of your association; I am proud of the honor you have this day conferred upon your Captain.

In looking forward, I have no fears for you in the future, whatever you may be called on to do—in garrison—in the tented field, or on the sanguined plain, it will be bravely—it will be well done. Then until rebels and traitors shall become extinct, or have grounded their arms, and acknowledged the supremacy of the government and the law, let this our motto be: Give us death or give us liberty.

In his own account of that event, Sergeant Alan Wilson noted that Captain Woodruff’s speech was received with three cheers by the men of D Company and a reception at which they ate and drank heartily in his honor.

Two days later, on Sunday, July 18, two privates from Company B—Charles Knauss and Allen Newhard—missed the regiment’s regularly scheduled inspection at Fort Taylor. Absent from morning through evening, they returned to their quarters. In response to their unexcused absence, their superior officers confined them to the guard house for three days and fined them each five dollars.

On July 22, Captain Henry S. Harte conducted a formal inspection of his F Company soldiers, who were dressed in full uniform and carrying their rifles for the event. That same day, B Company Private William Geist was reported as being drunk in his company’s barracks. Citing previous episodes of drunkenness, he was ordered by his superior officers “to stand upon the head of a barrel in front of the guard quarters for six successive days from 7 to 10 AM, and be confined in the guard house in the interval,” according to Schmidt.

In a letter penned around this same time, I Company Private Alfred Pretz wrote:

The weather is pleasant here, nothing short of it. Here we are set down on a small key in the ocean with the cooling sea breezes continually blowing over us so that, although the rays of the sun parch the ground and wither the herbage, the air in the shade is temperate. From 10 to 3 we keep in doors, the early mornings are fine, the evenings are cool. We have the moonlight at night now too which makes it delightful. I have just returned from Fort Taylor. Col. Good was here with his carriage at 12 and asked me whether I would ride back to the fort with him. Of course, I went transacted a little business for headquarters down there and walked back, over a mile. It would be impossible, I believe, to walk so far at this time of day if the breeze were not so strong and cooling. Tomorrow evening the Colonel is to be presented with a magnificent sword by the citizens of Key West ‘as a token of [their] appreciation of his merits as a gentlemen and soldier,’ so the Chairman of the Committee of Arrangements said at their meeting the other evening. The sword was made to order in New York and cost $750. I have not seen it. I will describe it to you as soon as I have seen it. The Yellow Fever season commences about the 1st of August. I don’t think we will have any of it this year, as there are none of the usual signs. We haven’t had a death in the regiment in the last month. There are few sick.

Colonel Tilghman H. Good, commanding officer, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (public domain image, circa 1863).

Colonel Good received that sword from the citizens of Key West during a festive event on Saturday, July 25, according to Schmidt.

At 4 PM, Companies C and D which were stationed at the barracks, were marched to Fort Taylor where Companies A, B, and I were stationed. The companies were formed in a line under command of Col. Good and marched through several street to the front of the Custom House, where they formed in a square column at 5 PM, with the Colonel on his horse ‘in his regular position’ in front of the troops. ‘A fine stand had been erected on the piazza of the building, seats were placed for the ladies, flags were stretched across the streets, and everything so arranged as to give it the appearance of a holiday. On the stand were Rear Admiral Bailey, Capt. Templeton of the Navy, Gen. Woodbury and staff, Captains Hook and McFarland of the Army; besides Thomas J. Boynton, U.S. District Attorney, for the Southern District of Florida.’

Two citizens came down from the platform and Col. Good dismounted from his horse and took his cap in his hand, stepped between the two men and was escorted to the platform at the cheers of his men. He was presented with the sword, sash, and belt by Mr. Maloney, a Key West lawyer.

Maloney then delivered the following address:

The people of Key West have called upon me to represent them today, and in their name and on their behalf to present you with a sword as a token of their regard, and in appreciation of your merits as a gentleman and soldier. And permit me to say, sir, that heretofore in instances almost without number have I been called upon to serve this people, during a residence of 28 years among them. And that many of those calls have been attended with positions of honor, trust, and emolument; but upon no occasion have I felt the honor more great, or my sympathies more in accord with the good people of this island, than upon the present occasion.

You first came to our island, sir, nearly two years ago. You came then as a subordinate, but at the head of a regiment, which had met the armed enemies of the government of the United States on the fields of Virginia, and had shown its discipline and bravery in battle, which attracted the favorable attention of the General soon after appointed to the command of this island; and which caused your regiment to be selected by him to serve under his command at this point.

Transferred from Virginia to Key West. From scenes of carnage to the peaceful abode of an unarmed and loyal people, you met the inhabitants of this island, as they deserved to be met and as they met you, and all who came before you bearing the flag of the Union and the command at this post.

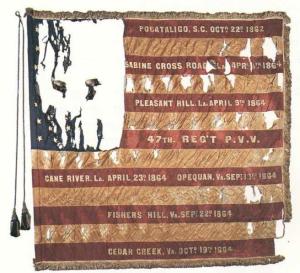

After a very short sojourn on the island, but not before you had succeeded in making a favorable impression on the inhabitants, the government found it necessary to transfer your regiment to South Carolina where it was expected fighting was to be done. And it was with pride and pleasure that your friends here learned that you met the enemy at Pocotaligo and Jacksonville and demonstrated that the most modest could be the most brave.

Unfortunately for us, sir, the transfer operated to bring into chief command on this island, one who had yet to learn to meet an armed foe. And I refrain from speaking of the administration, or more correctly speaking, the maladministration of that officer only because he is absent.

Wiser councils, and a good providence returned you to us, as chief in command, at a moment of great peril to a large number of our inhabitants, and you signalized your assumption of command by inaugurating renewed confidence in the good faith of the government of the United States. By discountenancing a vile system of clandestine attacks upon the reputation of quiet law abiding citizens. And by bringing order out of general confusion.

Your administration of affairs as chief of command was short, but such as to attract the respect sand esteem of the greater portion of the people of this island; and without disparagement to others, I can confidently say that no military officer of the United States more wisely and prudently governed on this island than yourself.

The citizens of Key West, in appreciation of your merits as a gentleman and a soldier, through me, now present this sword, asking your acceptance of the same, confident that they confide it to the hands of an officer who knows both how and when to use it.

In response, Colonel Good said:

Gentlemen, I accept at your hands this magnificent gift, and beg of you to accept in return my most heartfelt thanks. Duly sensible that no acts of mine as an individual have merited it, I shall regard the presentation of this testimonial as evidence of your attachment to the cause I have the honor to represent, and of your devotion to our common country. It shall ever serve as an additional memento, if one were needed, to remind me of the pleasant days passed among you, and of the loyalty of your citizens, to whom I am already greatly indebted for many kindnesses. It shall be sacredly preserved and I hope no act of mine will ever disgrace it or cause you to regret of your generosity. I am a man of action, gentlemen, and I know you will in these times, particularly, excuse a lengthy speech from me, it not being a soldier’s vocation. Imagine all a grateful heart could prompt the most eloquent to utter, and you will have the correct idea of my feelings.

A reception then followed, during which the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band performed Bully for You and other numbers and the assembled crowd of Key West residents and men from the 47th Pennsylvania gave rousing cheers for Colonel Good, the Army and Navy of the United States and its senior military officers, President Abraham Lincoln, and America’s Union. As the event wound down, the regiment’s various companies marched back to their respective quarters.

August 1863

Officers’ quarters and parade grounds, interior of Fort Jefferson, Dry Tortugas, Florida, 1898 (U.S. National Park Service and National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

During the month of August, forty-nine of the inhabitants of Fort Jefferson were admitted to the fort’s post hospital, twenty-nine of whom were members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Among those admitted from the regiment were twenty-five soldiers who had contracted infectious or inflammatory diseases or developed other types of infections. Conditions identified during this period included: anthrax/fungus infections (two cases), bilious remittent or intermittent fevers (nine cases); conjunctivitis; constipation, dysentery/diarrhea, enuresis/bed wetting or other intestinal complaints (eleven cases); funiculitis and orchitis, as well as cases of cramp, debilitas, hemorrhage, and rheumatism.

That same month, the men stationed at Fort Jefferson continued their routine of morning infantry drills, followed by artillery practice in the afternoon, with Second Lieutenant Christian K. Breneman appointed as the fort’s post adjutant, Company K’s First Lieutenant David Fetherolf appointed as “A.A.G.M. & A.A.C.S. of Post in accordance with Spec. Order #98 HQ Fort Jefferson,” and Privates Alexander Blumer (Company B), Charles Detweiler (Company A), John Schweitzer (Company A), Charles Shaffer (Company E), and John Weiss (Company F) assigned to responsibilities, respectively, as a company clerk, nurse, baker, quartermaster department member, and ordnance department member. In addition, other members of the regiment were assigned to guard duty.

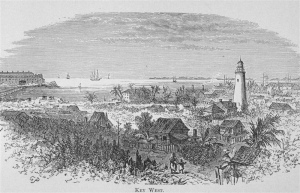

Lighthouse, Key West, Florida, early to mid-1800s (Florida for Tourists, Invalids, and Settlers, George M. Barbour, 1881, public domain).

Their routine changed dramatically for one day, however; on Thursday, August 6, 1863—the date President Abraham Lincoln had proclaimed as a nationwide day of Thanksgiving and reflection—and a date on which 47th Pennsylvanians at both of garrison sites most certainly took time to reflect on all that they had endured since enlisting.

While the majority of enlisted men and lower ranking officers stationed in the Dry Tortugas observed the national holiday there at Fort Jefferson, many of their superior officers headed to Fort Taylor, where every store in town was closed to ensure wider participation in the commemorative events that had been scheduled there, which C Company’s Henry Wharton described in his August 23, 1863 letter to the Sunbury American:

Thanksgiving, or the day set apart by the President for prayer and to return thanks to Him who has the control of battles, was properly observed by the Army and Navy at this place. The proclamation of the President was read from the pulpits of the different churches on the Sunday evening previous, and invitation extended to all who wished to participate in the services on that occasion. General Woodbury issued a circular requesting all of his command to observe the day in a becoming manner and to attend Divine service at their usual places of worship.– He ordered that all drills and policeing [sic] should be dispensed with, so that the men were at liberty to spend the day as their feelings best dictated. The invitation of the Clergy was accepted, and the Military, by companies attended church. Company C, headed by Captain Gobin and Lieutenant Oyster, marched to the Episcopal church, where an eloquent discourse was delivered by the Rev. Dr. Herrick, but owing to the great crowd many were compelled to retire, thus losing an intellectual treat that would have benefitted them more than the mere listening to a common sermon. The Reverend gentleman of this church has been very kind to our regiment in reserving seats for their accommodation. One act of his speaks for itself, viz: on our arrival here he addressed a note to the Colonel of the 47th, inviting the officers and men to attend the services at St. Marks church, and mentioned particularly that the seats were free.

On the Saturday following Thanksgiving a Yacht race came off on the waters between Sand Key Light House and Key West.– Some thirty boats were entered. Boats of all kinds, from a Captains gig to a thirty or forty ton schooner. The wind was fine and a splendid day they had for the purpose.– Each boat had a flag that it might be known, and as they moved off, the fleet made a grand display. From the ramparts of Fort Taylor the sight was magnificent, for from that point one had a full view, and an opportunity afforded of following the different parties, with the eye, until they gained the turning point and their return to the starting ground. A steam tug followed the party, having on board ladies, the committee and guests, who had a jolly time of it, and an opportunity of tripping the ‘light, fantastic toe,’ to the fine music of the 47th Band, lead by that excellent musician, Prof. Bush. Quartermaster Lock’s schooner ‘Nonpareil’ won the race, out distancing all of its competitors. Of that fact I was certain, for how else could it be, when its name belongs to the ‘art, preservative of all arts’ – printing.

Last Wednesday brought two-thirds of the ‘three years’ of the ‘Sunbury Guards’ to a close, when Lieut. Reese surprised the boys, agreeably, by giving them an entertainment. In this the Lieut., took the start of the other officers of the company, but as all joined in devouring the good things furnished, every one was in a good humor and satisfied, no matter who was the caterer for the occasion. Company C is blessed with good officers – men who do, as they wish to be done by. This little celebration had a good effect, for if there was any misunderstanding, previously, it is now settled, and no better conducted or well regulated family, where good feeling are exhibited, can be found among the soldiers of Uncle Sam. Our company is slightly envied on account of their good grub, but for this the boys should not be blamed for Gobin, who has charge of the company savings, is continually hunting the market for the best it affords, and Sergeant Piers and Johnny Voonsch serve it up in their best style, proving to others that soldiers can, if they good [sic] cooks, live a well as any ‘other man.’

The nomination of Governor Curtin for re-election was well received, and if they had the right to vote there would be no fear of the next Chief Magistrate of Pennsylvania being a copperhead. The decision of Judge Woodward, depriving the soldier of a vote, is looked upon as a bribe for not re-enlisting; and indeed it is, for does it not give the bounty of the right of suffrage to every elector who stays at home? The voting men of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteers, are as a unit for the re-election of Andrew G. Curtin.

Blockade running is nearly played out, and is confined to Mobile and Wilmington, N.C. Very few vessels of this sort are brought into this port at present, owing to the strict watch that is kept on the above named places; however, a day or two ago, the U.S. Steamer De Soto brought in two very large river steamers laden with cotton. The cotton is being transferred to other vessels and will soon be sent North, where it will be put in market for sale.

One of the houses belonging to the Engineer Department was entirely destroyed by fire on last Thursday. It was occupied by the laborers as a sleeping apartment. How the fire originated is unknown, but it is supposed to have caught from a tobacco pipe of one of the men, or from a spark of the locomotive that is used in hauling material for the outside works at Fort Taylor. The boys are all very well and in fine spirits, only a little more active life, and occasional brush with the enemy, they think, would give them a better appetite and enable them to enjoy the rations fournished [sic] by Government….

As the month of August wore on, one of the 47th Pennsylvanians assigned to guard duty at Fort Jefferson was H Company’s Corporal George W. Albert, who was stationed at the wharf in the Dry Tortugas on August 24. Standing guard at the regimental post designated as No. 6, he was assigned to night duty, and was relieved the next morning at 8 a.m.

That same day, General Woodbury arrived at the Tortugas for an inspection. He was impressed by the regiment’s level of discipline according to H Company Captain James Kacy, who later wrote: “Men were fully armed and ready for march, splendid appearance…. Gen. Woodbury would not part with the 47th if he does not have to, and all the people at Key West and the Tortugas are pleased with the 47th more than any other regiment.”

With respect to the civilian population at Fort Jefferson and across Florida’s Dry Tortugas, life was also often surprisingly busy. According to Emily Holder, who was making a life with her physician-husband at a house on the fort’s grounds during this time:

The latter part of August 1863, Mr. Hall, who with his wife, had been long with us, was ordered away. He was a very efficient officer and we heard long afterwards that his bravery under fire was remarkable. Their departure was most tantalizing to them and to us somewhat amusing. It showed more clearly than anything else would our isolated condition, for our only legitimate means of getting away was by sail; whenever we had steam conveyance it was by special favor.

We had given some farewell entertainments to Mr. And Mrs. Hall, and Saturday afternoon saw them on board the boat that was to carry them directly to Pensacola. When ready to sail the wind suddenly failed, and the vessel could not get away from the wharf.

The doctor went down and brought them back with him to tea after which they returned to the boat, hoping that during the night a breeze would spring up, but in the morning there the boat lay, and they breakfasted with the colonel. Later all went down again to see them off, as a breeze gently flapped the flag, but it was dead ahead, making it impossible to get out of the narrow channel, which in some places was not wide enough for two vessels to pass each other, and beating out was impossible, so they came up to tea again and spent the evening.

The next morning the doctor looked out of the window and exclaimed: “There they go!” when suddenly as we were watching, the masts became perfectly motionless. We knew only too well what that meant. They had run on to the edge of the reef, within hailing distance of the Fort, and the doctor with others, went out and spent the morning with them, as they refused to come on shore again. Mr. Hall said he was going to “stand by the ship.”

In the course of the day, by kedging as the sailors call it, putting out the anchor and pulling the boat up to it, then throwing it out again further on, they managed to crawl to the first buoy, and there lay in the broiling sun….

Someone replied that it was fortunate that the Wishawken had captured the Atlanta and that the Florida after running the blockade from Mobile under the British colors, rarely came near our coast, for they certainly would have been captured had there been a privateer in those waters.

The next morning when we went on top of the Fort, the sails of the schooner were just a white speck on the northern horizon, and we could hear music from the steamer, which was bringing Colonel Goode [sic] for his monthly inspection of the troops.

Our rains continued occasionally later than usual, one in the middle of September almost ending in a hurricane; so rough was it that the Clyde, a long, graceful, English-built steamer, that came in for coal with the Sunflower, had to remain several days. The Clyde had quite a serious time in reaching the harbor. We watched it through a porthole with great anxiety. It was too strong a wind for us to venture on the ramparts, but we could walk all about inside seeing everything that came in from our safe lookout.

Colonel Goode [sic] on his last trip had left the regiment band for us awhile, so that guard mount and dress parade were important features, while the naval officers went about visiting the various houses, keeping us bright and gay while they were weather bound.

The high winds ended in a severe norther—an almost unheard of thing so early in the season. Later we saw by a paper that they had snow in New York the latter part of August; it might have been the same cold wave that swept down over the Gulf, for it housed us shivering.

While the band was with us the ramparts were the favorite places for viewing dress parade, and the colonel gave the ladies all the pleasure he could, having the band play on parade during the evening.

A remittent fever broke out and we were ill for three weeks. It was very much like the break-bone fever; extreme suffering in the limbs and back seemed to be the prevailing feature of the attacks. At the same time they were digging a ditch around close to the wall of the Fort, which made it pass between the house and kitchen as the latter was in the casemates.

The rains, of course, swelled the size of the brook so that the bridge over it, when the wind blew, as it seemed to most of the time, was rather an insecure passage, as it was five feet wide and from three to four deep, and to cross that every time one went into the kitchen was no small annoyance, and the contrivances to get the meals into the dining-room got required no little ingenuity.

Meanwhile, as summer progressed, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers continued to weaken Florida’s abilities to supply and transport food and troops throughout the area held by the Confederate States of America by capturing livestock and farm produce, as well as disrupting the manufacture of salt.

They also continued to train, keeping their battle skills sharp in readiness for the moment they would be ordered back into the fray in order to finally extinguish the faction of “fire-eaters” bent on dissolving the United States and all that the nation had stood for since its founding.

Sources:

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War: ‘Supplier of the Confederacy.’” Tampa, Florida: Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida, retrieved online January 15, 2020.

- Holder, Emily. “At the Dry Tortugas During the War.” San Francisco, California: Californian Illustrated Magazine, 1892 (part four, retrieved online, March 28, 2024, courtesy of Lit2Go, the website of the Educational Technology Clearinghouse at the Florida Center for Instructional Technology, College of Education, University of South Florida).

- “History: Crops (Historic Florida Barge Canal Trail).” Historical Marker Database, retrieved online December 30, 2023.

- Owsley, Frank Lawrence, and Harriet Fason Chappell. King Cotton Diplomacy: Foreign Relations of the Confederate States of America. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press, 1959.

- “Preventing Diplomatic Recognition of the Confederacy, 1861–1865,” and “The Alabama Claims, 1862–1872,” in “Milestones: 1861–1865.” Washington, D.C.: Office of the Historian, Foreign Service Institute, United States Department of State, retrieved online December 30, 2023.

- Schmidt, Lewis G. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Wharton, Henry. Letters from the Sunbury Guards. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1861-1868.

You must be logged in to post a comment.