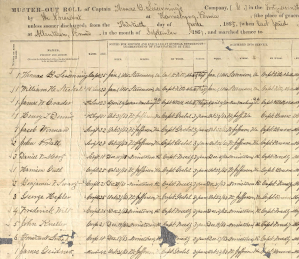

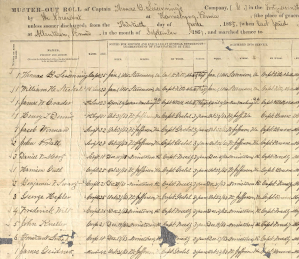

Excerpt of muster-out roll, Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, December 25, 1865, page one (Pennsylvania Civil War Muster Rolls, Pennsylvania State Archives, public domain; click to enlarge).

The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania’s collection of Civil War-era muster rolls is another of the three major tools that beginning, medium and advanced researchers initially turn to for help in determining which Pennsylvania military unit(s) a soldier served with during the American Civil War. Unfortunately, it is also a resource that often does not receive the close attention from researchers that it should.

Those who have chosen to spend significant time looking through the individual documents contained in this collection have come to understand that, in addition to confirming the identity of a soldier’s regiment and company, as well as his rank(s) at enrollment and final discharge, Pennsylvania’s Civil War-era muster rolls are also useful for documenting when and where that soldier enrolled and mustered in for service and whether or not he had some change to his status while serving, such as a promotion, reduction in rank or charge of desertion — and possibly data which documented whether or not he was wounded or killed in battle and, if so, when and where.

Physically created as hard-copy index cards that were later preserved by the Pennsylvania State Archives in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, as part of the “Civil War Muster Rolls and Related Records” group of documents from the Pennsylvania Department of Military and Veterans Affairs’ archives (Series RG:-019-ADJT-11, 1861-1866, 1906), this collection includes muster rolls from each of Pennsylvania’s volunteer infantry and volunteer militia regiments, emergency volunteer militia regiments that were formed during the summer of 1863 in response to the looming invasion of the commonwealth by the Confederate States Army, United States Colored Troops (USCT), United States Veteran Volunteer regiments and Hancock Veterans Corps, regiments of the Veterans Reserve Corps, and independent or other unattached units. Preserved on microfilm decades ago by the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, a portion of this large collection has since been partially digitized and made available on the Ancestry.com website as “Pennsylvania, U.S., Civil War Muster Rolls, 1860-1869.”

* Note: Although Ancestry.com is a subscription-based genealogy service that generally requires users to pay for access to its records collections, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania entered into a partnership with Ancestry.com several years ago “to digitize family history records in the State Archives and make them available online.” As part of that agreement, Ancestry.com created Ancestry.com Pennsylvania to provide free access to Pennsylvania residents to the Pennsylvania records it has digitized. If you reside in Pennsylvania and want to learn more about how you may obtain free access to those records, please contact the Pennsylvania State Archives for guidance. If you reside elsewhere, check with your local library to determine if it offers access to Ancestry.com as part of its service to library users.

What May Researchers Find with This Resource?

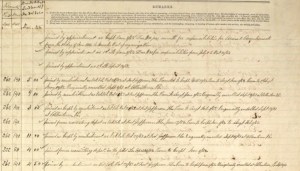

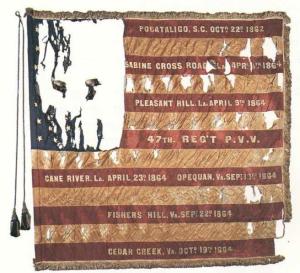

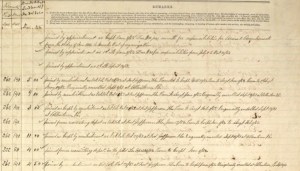

Excerpt from muster-out roll, Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, December 25, 1865, showing soldiers’ promotions, status as Veteran Volunteers, etc. (Pennsylvania State Archives, public domain; click to enlarge).

According to personnel at the Pennsylvania State Archives, Pennsylvania’s Civil War Muster Rolls and Related Records collection includes:

“Alphabetical Rolls. The rolls are arranged alphabetically by the soldiers’ surnames. Entries usually give the name, rank, civilian occupation, and residence, the unit, regiment, company, and commanding officer, and the date and place where the roll was taken. Particulars about sickness or injury are also sometimes noted.

“Descriptive Lists of Deserters. Lists give the names, ages, places of birth, height, hair and eye color, civilian occupations, and ranks of deserters, the units, regiments, and companies to which they were assigned, and the dates and places from which they deserted.

“Muster-In Rolls. Entries usually list the name, age, rank, unit, regiment, and company of the soldier, the date and place where enrolled, the name of the person who mustered him in, the term of enlistment, the date of mustering in, and the name of commanding officer. Remarks concerning promotions and assignments are sometimes recorded.

“Muster-Out Rolls. The dated lists ordinarily give the soldier’s name, age, rank, unit, regiment, and company, the date, place, and person who mustered him in, the period of enlistment, and the name of the commanding officer. Particulars concerning pay earned, promotions, capture by the enemy and the like also regularly appear.

“Muster and Descriptive Rolls. Generally the rolls give the name, age, town or county and state or kingdom of birth, civilian occupation, complexion, height, eye and hair color, and rank, the unit, regiment, company and commanding officer, and the amount of money received for pay, bounties, and clothing. Rolls for assigned United States black troops are included in this group. Included throughout are such related materials as regimental accounts of action, and correspondence related to infractions of military procedures, correspondence from soldiers addressed to the governor expressing grievances or petitioning for promotion.

“The data found in the documents of this series were used to create the Civil War Veterans Card File, 1861-1866 (Series 19.12).”

Be Sure to Look for Data Regarding Soldiers’ Pay

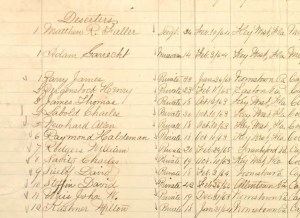

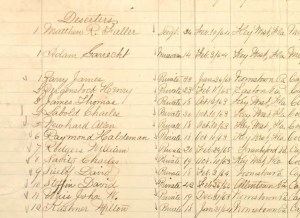

Excerpt from muster-out roll for Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, showing soldiers’ pay data, December 25, 1865 (Pennsylvania State Archives, public domain).

One of the most fascinating features found on the muster-out rolls for Pennsylvania volunteer soldiers is that many of the infantry unit clerks took the time to meticulously record the pay data for multiple members of their respective regiments. As a result, present-day researchers are often able to determine how much bounty pay a particular soldier was eligible for at the time of his enlistment — and how much of that promised pay he actually received, as well as how much money he still owed the United States government for his army uniform, rifle and ammunition at the time of his discharged from the military.

Another striking feature on the muster-out rolls is the “Last Paid” column, which corroborates the shocking fact that many Union Army soldiers were expected to perform their duties, even though they were not being paid regularly — a data point that also may help to shed light on why some soldiers’ families faced greater hardship than others (because some soldiers were able to send part of their pay home while others were not).

Caveat Regarding Ancestry.com’s Collection Related to the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry

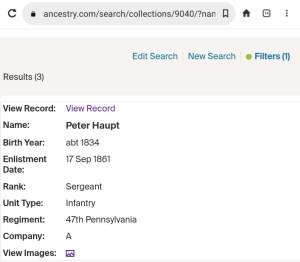

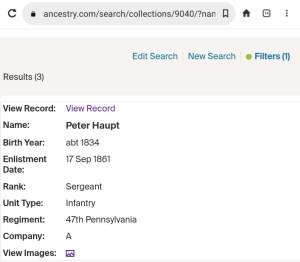

Screenshot of Ancestry.com’s record detail page for Peter Haupt, which incorrectly identifies him as a member of Company A, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, instead of Company C (fair use for illustration purpose, October 2025).

Although Ancestry.com’s collection of Pennsylvania Civil War-era muster rolls can be a useful tool for researchers, there is a significant problem with records related to the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry that merits closer scrutiny — the inaccurate transcription of soldiers’ data. That scrutiny is needed because the muster rolls from the 47th Pennsylvania’s Company C were mixed together with the muster rolls from Company A when they were posted to Ancestry.com’s website, making it appear, when browsing through those rolls, that all of the soldiers listed on every single one of those incorrectly grouped muster rolls were all members of Company A, when they were not.

Complicating things further, the Ancestry.com personnel who were assigned to transcribe the data from each of those muster rolls and create Record Detail pages for each individual soldier that summarized each soldier’s data from the muster roll on which it appeared, apparently did not realize that the muster rolls from Companies A and C of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had been mixed together. As a result, those transcribers incorrectly described every soldier from that improperly sorted muster roll group as a member of Company A, when they were not. (See attached image.)

So, when reviewing Ancestry.com’s collection of muster rolls, it is vitally important that researchers not take the transcribed data found on any of the Record Detail pages of 47th Pennsylvania muster rolls at face value. Instead, researchers should double check the data found on those muster rolls for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry against the data for individual soldiers published by Samuel P. Bates in his History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, volume 1, and should also then re-check that data against the information of individual soldiers that is contained in the Pennsylvania Civil War Veterans Index Card File, 1861-1866.

* Note: This is particularly important if you are a family historian who is hoping to identify the specific company in which your ancestor served. (And you will definitely want to know which company your ancestor served with because each company of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was assigned to different duties in different locations at different times during the regiment’s service.)

Caveat Regarding “Deserters”

Private Milton P. Cashner, Company B, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, was incorrectly labeled as a deserter on this regimental muster roll from the American Civil War (Pennsylvania State Archives, public domain; click to enlarge).

If a muster roll entry for your ancestor noted that he was a deserter, it’s also important that you not take that label at face value, either, because that data may also be incorrect. Military records from the Civil War era contained a surprising number of errors, a fact that is understandable when considering what the average army clerk was expected to do — keep track of more than a thousand men, many of whom ended up becoming separated from their regiment and confined to Union Army hospitals after being wounded in battle. (Wounded too severely to identify themselves to army personnel, they were then often mis-identified by army hospital personnel and then also incorrectly labeled as “deserters” by their own regiments because they hadn’t shown up for post-battle roll calls.) So, it’s important to double and triple check the data for any ancestor who was labeled as a “deserter” because he might actually have been convalescing at a hospital and not absent without leave.

Honoring Our Ancestors

One of the best ways to honor ancestors who fought to preserve America’s Union is to pass their stories along to future generations. No embellishment required. Their willingness to volunteer for military service and the bravery they displayed as they ran toward danger and certain death during one of America’s darkest times speaks for itself.

Our job, as students of American History, educators and family historians is to ensure that their stories are told as accurately and thoroughly as possible so that their valor and love of community and country are never forgotten.

Remember their names. Tell and re-tell their stories. Honor the sacrifices that they made.

Sources:

- “Ancestry Pennsylvania,” in “Agencies: Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission,” in “Pennsylvania State Archives.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, retrieved online October 25, 2025.

- “Civil War Muster Rolls and Related Records” (resource description). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives, retrieved online October 30, 2025.

- “Pennsylvania,” in Collections. Lehi, Utah: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2021 (retrieved online October 25, 2025).

You must be logged in to post a comment.