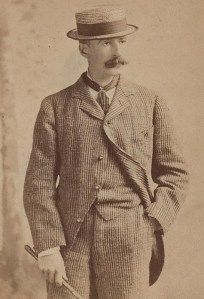

Winslow Homer (1836-1910) was a Boston native who became one of the most important artists in nineteenth-century America. Best known for his pastoral landscapes and seascapes, he was also a notable chronicler of the lives of average American Civil War-era soldiers.

Apprenticed to Boston lithographer J. H. Bufford during the mid-1850s, he subsequently turned down a job offer by Harper’s Weekly later that same decade to become a staff illustrator, choosing, instead, to make his living as a freelancer and founder of his own art studio in New York City.

American Civil War

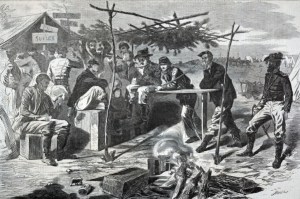

“The Civil War Surgeon at Work in the Field,” Winslow Homer, 12 July 1862 (National Library of Medicine, public domain).

During the early 1860s, however, Winslow Homer was ultimately persuaded to serve as a war correspondent for Harper’s Weekly, leading him to create some of the most evocative illustrations of the American Civil War era.

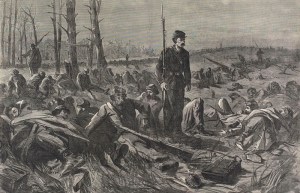

In 1862, for example, he showed Americans what it was like to be “The Civil War Surgeon at Work in the Field” by sketching a group of Union Army surgeons and wounded soldiers and then turning that sketch into a powerful illustration for a July edition of Harper’s Weekly. In November of that same year, he documented “A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty,” perched high up in a tree in the Virginia countryside, protecting his fellow members of the Army of the Potomac.

That same month, he also preserved, for all time, a Thanksgiving celebration of one pensive group of Union Army soldiers who were stationed far from the arms of loved ones.

Why Was His Work So Popular?

Homer’s work captured the hearts and minds of Harper’s Weekly readers for three simple reasons. He had a great eye and great instincts to match his great skills as an illustrator.

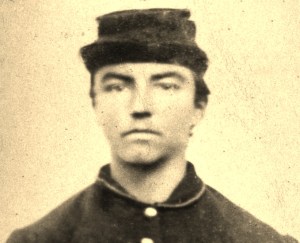

According to a 2015 Yale News article about Homer by Amy Athey Mcdonald, “Artist-reporters” of the Civil War era “had to be more than merely good draftsmen. They had to be astute observers, have an instinct for story and drama, the ability to sketch quickly and accurately, and no small amount of daring, as they faced battles, injuries, starvation, and disease first hand.”

Post-War Life

After the Civil War ended, Winslow put a fair amount of distance between himself and the United States. In 1866, he traveled to France, where he spent ten months studying and honing his skills. According to the late H. Barbara Weinberg, a renowned American art scholar and former curator at The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City, “While there [was] little likelihood of influence from members of the French avante-garde” during this phase of Homer’s life, “Homer shared their subject interests, their fascination with serial imagery, and their desire to incorporate into their works outdoor light, flat and simple forms (reinforced by their appreciation of Japanese design principles), and free brushwork.”

Recognized as a master of oil painting in the United States by the 1870s (while still just in his thirties), he also began to explore his talent as a watercolor artist.

And, he began to document the post-war lives of men and women who had been freed from chattel enslavement. Painted in oil in 1876, “The Cotton Pickers” illustrated the harsh reality of the Reconstruction era–that many Freedmen and Freedwomen were still engaged in the same backbreaking work that they had endured while enslaved before the war. According to author Carol Strickland, “Although the artist left scant record of his convictions about race, his paintings of Black people are unlike those of his contemporaries.”

When speaking to Strickland for a 2022 profile of Homer, Associate Professor Gwendolyn DuBois Shaw observed that “before Emancipation, artists had elicited sympathy for enslaved people by portraying them on the auction block, for example. But the market for such work evaporated after the 1860s…. Caricatures derived from minstrel shows appeared in paintings, but ‘it was really unusual for Homer to stake so much on Black subjects connected to Reconstruction.'” His work in this regard, however, was not only limited to the Reconstruction era; in later years, he depicted the struggles of the Black men, women and children that he met while visiting the Bahamas.

But it was, perhaps, through his paintings of the sea that he became best known to a wider audience across America. According to Weinberg:

He enjoyed isolation and was inspired by privacy and silence to paint the great themes of his career: the struggle of people against the sea and the relationship of fragile, transient human life to the timelessness of nature.

Sources:

- McDonald, Amy Athey. “As Embedded Artist with the Union Army, Winslow Homer Captured Life at the Front of the Civil War.” New Haven, Connecticut: Yale News, 20 April 2015.

- Strickland, Carol. “Not Just Seascapes: Winslow Homer’s Rendering of Black Humanity.” Boston, Massachusetts: The Christian Science Monitor, 7 June 2022.

- “Thanksgiving in Camp (from ‘Harper’s Weekly,’ Vol. VII).” New York, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, retrieved online 28 November 2024.

- “The Army of the Potomac — A Sharp-Shooter on Picket Duty (from ‘Harper’s Weekly,’ Vol. VII).” New York, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, retrieved online 28 November 2024.

- Weinberg, H. Barbara. “Winslow Homer (1836-1910).” New York, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, October 2004.

You must be logged in to post a comment.