Unidentified Union infantry regiment, Camp Brightwood, Washington, D.C., circa 1865 (public domain; click to enlarge).

Marched closer to the nation’s capital in the wake of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in mid-April 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were directed to proceed to the Brightwood district in the northwestern section of Washington, D.C. and erect their Sibley tents at the Union Army duty station known as Camp Brightwood.

Their new job was to prevent Confederate States Army troops and their sympathizers from reigniting the flames of civil war that had just been stamped out weeks earlier.

According to historians at Cultural Tourism DC, Brightwood was “one of Washington, DC’s early communities and the site of the only Civil War battle to take place within the District of Columbia” — the Battle of Fort Stevens.

This crossroads community developed from the Seventh Street Turnpike, today’s Georgia Avenue, and Military Road. Its earliest days included a pre-Civil War settlement of free African Americans…. Eventually Brightwood boasted a popular race track, country estates, and sturdy suburban housing. In 1861 the area was known as Brighton, but once it was large enough to merit a U.S. Post Office, the name was changed to Brightwood to distinguish it from Brighton, Maryland.

Also, according to Cultural Tourism historians, Camp Brightwood was established on the grounds of “Emery Place, the summer estate of Matthew Gault Emery,” who had “made a fortune in stone-cutting, including the cornerstone for the Washington Monument,” which was laid in 1848.

During the Civil War (1861-1865), Captain Emery led the local militia. His hilltop became a signal station where soldiers used flags or torches to communicate with nearby Fort DeRussy or the distant Capitol. Soldiers of the 35th New York Volunteers created Camp Brightwood here. During the Battle of Fort Stevens in July 1864, Camp Brightwood was a transfer point for the wounded.

By late April of 1865, it was home to multiple Union Army regiments, including the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers.

Guarding the Lincoln Assassination Conspirators

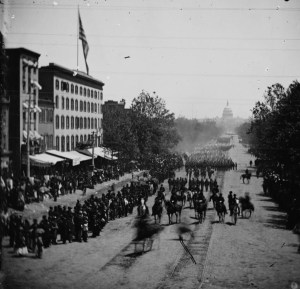

Washington Arsenal Penitentiary, Washington, D.C., 1865 (Joseph Hanshew, public domain; click to enlarge).

Sometime after their arrival at Camp Brightwood during that fateful spring of 1865, a group of 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers were given a new assignment — guard duty at the Washington Arsenal and its prison facility, where eight people were being held in connection with their involvement in the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln. They had been arrested between April 17 and 26.

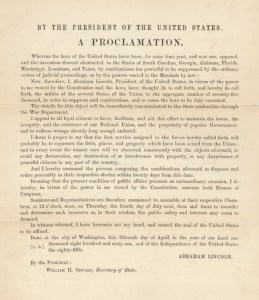

The key conspirators involved in President Abraham Lincoln’s assassination (Benn Pitman, The Assassination of President Lincoln and the Trial of the Conspirators,” 1865, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

While researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have not yet determined the exact start date of the 47th Pennsylvania’s guard duties at the Washington Arsenal Penitentiary, they are now able to offer a better estimate — thanks to the work of Lincoln scholars Edward Steers, Jr. and Harold Holzer, who published documents written by Union Major-General John Frederick Hartranft, the Pennsylvanian appointed by U.S. President Andrew Johnson on May 1, 1865 “to command the military prison at the Washington Arsenal, where the U.S. government had just incarerated the seven men and one woman accused of complicity in the shooting.” Included in the Steers-Holzer compilation is a letter from Major-General Hartranft, governor and commander of the “Washington Arsenal Military Prison,” to Major-General Winfield S. Hancock, commanding officer of the United States Middle Military Division, which was dated May 11, 1865. Hartranft began by informing Hancock that “at 10:25 yesterday [May 10, 1865], Lt. Col. J. M. Clough, 18th N. H. reported with 450 muskets, for four days duty, relieving the 47th Pa. Vols.” He then went on to describe the duties performed by 18th New Hampshire Volunteers at the Washington Arsenal on May 10:

At 11:45, the prisoners on trial were taken into Court, in compliance with the orders of the same. At 1 P.M. the Court ordered the prisoners returned to their cells, which was done.

At 1:10 P.M. dinner was served to the prisoners in the usual manner.

At 1:30 in compliance with your orders Marshal McPhail was admitted to see the prisoner in 161 [Atzerodt], his hood having been previously removed; he remained with him until 2.35, immediately after which his hood was replaced and the door locked.

At 3:45 P.M. Mr. George L. Crawford in accordance with your instructions, was permitted to have an interview with prisoner in 209. I was present during the same, and heard all that was said. The conversation was in regard to the property of the prisoner in Philadelphia. At 4:25 the hood was replaced and the cell locked.

At 6 P.M. Supper was furnished the prisoners and at the same time Dr. Porter and myself made inspections of all the cells and prisoners.

At 6 P.M. in accordance with your instructions, Mr. Stone, counsel for Dr. Mudd, was permitted to visit his client. The interview took place in the presence of Lt. Col. McCall but not in his hearing.

At 6:35 the interview closed, and the door was again locked.

At 7 this A.M. breakfast was served to the prisoners in the usual manner. At 7:15, Dr. Porter and myself made Inspections of all the cells and prisoners.

I would respectfully recommend that the prisoner in 190 be removed to cell 165.

All passes admitting persons during the last 24 hours are here with enclosed.

As a result, researchers for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ project postulate that:

- As many as four hundred and fifty 47th Pennylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantrymen may have been stationed at the Washington Arsenal between May 6-10, 1865; and

- At least some of those 47th Pennsylvanians may very well have interacted with the key Lincoln assassination conspirators (Samuel Bland Arnold, George A. Atzerodt, David E. Herold, Dr. Samuel Alexander Mudd, Michael O’Laughlen, Lewis Thornton Powell/Lewis Payne, Edman Spangler/Ned Spangler, and Mary Elizabeth Surratt) — interactions which likely took place while those eight prisoners were confined at the Washington Arsenal prison; on the way to and from the courtroom, where they were being tried for conspiring to assassinate President Lincoln; inside that courtroom during trial proceedings; and possibly also at other sites related to their confinement and trial.

Although the duties performed between by 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers between May 6-9 would not have been exactly the same as those performed by the New Hampshire soldiers on May 10, they may very well have been similar — meaning that at least some 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers may have been involved in locking and unlocking the doors of the conspirators’ cells, escorting the conspirators into the courtroom of their military trial (which began on May 9, 1865), standing guard over the conspirators during their trial to prevent their escape, escorting them from the courtroom, and interacting with them in their cells by:

- Bringing meals to them;

- Removing and replacing the hoods that covered their heads so that they could interact with their lawyers and other visitors;

- Verifying the legitimacy of passes held by would-be visitors and denying or granting access to those visitors as appropriate;

- Escorting visitors to and from their cells; and

- Monitoring their visits with anyone granted entry to their cells.

With their guard assignment completed by the morning of May 10, 1865, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers who were serving on detached duty at the Washington Arsenal were marched back to Camp Brightwood, where they would remain until their next assignment — participating in the Union’s Grand Review of the National Armies on May 23, 1865.

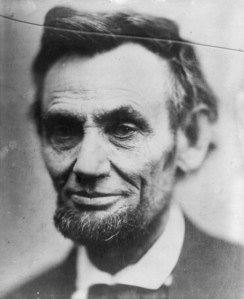

19th Corps, Army of the United States, Grand Review of the National Armies, Pennsylvania Avenue, Washington, D.C., May 23, 1865 (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The Grandest of the Grand Reviews

The 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry was just one group of the more than one hundred and forty-five thousand Union military men who marched from Capitol Hill through the streets of Washington, D.C. during a two-day spectacle designed to celebrate the end of the American Civil War and heal Americans’ heartbreak in the wake of President Lincoln’s assassination. Held from May 23-24, 1865, it was a sight that had never been seen before — and one that would likely never be seen anywhere in the United States of America ever again. The first day’s parade alone lasted six hours.

Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant, leaning forward, President Andrew Johnson to his left, Grand Review of the National Armies, Washington, D.C., May 23, 1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

According to The New York Times, the 47th Pennsylvanians were positioned behind the parade’s third division, as part of the Nineteenth Army Corps (XIX Corps) in Dwight’s Division. Marching with the precision for which they had become renowned, they passed in front of a review stand which sheltered U.S. President Andrew Johnson, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton and Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant. The division directly behind the 47th Pennsylvanians in that day’s line of march included other officers and general staff of the Army of the United States and regiments commanded by American Civil War icon Brigadier-General Joshua L. Chamberlain, one of the most beloved heroes from the tide-turning Battle of Gettysburg.

Rev. William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock, chaplain, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (courtesy of Robert Champlin, used with permission).

Afterward, 47th Pennsylvania Chaplain William DeWitt Clinton Rodrock summed up the experience in a report penned at Camp Brightwood on May 31:

The wise king of the Scriptures speaks of a sorrow that pervades the human heart “in the midst of laughter.” The truthfulness of this Divine philosophy is a matter of daily experience. Our most joyous seasons are intermingled with a sadness that often challenges definition. Every garden has its sepulchre. Every draft of sweet has its ingredient of bitter. This fact has never been so fully realized as this month. With the mighty army of brave soldiers congregated and reviewed in Washington and the … expressions of deep regret that Abraham Lincoln is not here to have witnessed the great pageant of the 23rd and 24th inst. have been universal. Not the splendid victories which our brave soldiers have won — not the pleasing prospect that they are “homeward bound” — not the consolatory thought that the reins of government have fallen into the hands of so good a man as Andrew Johnson — have served to restrain these utterances of grief and sorrow. Had it been God’s will to spare Mr. Lincoln’s life, what an eclat his presence would have imparted to the mighty pageant.

But as He willed otherwise and “doeth all things well,” it is ours to learn the great lesson of the hour.

Rebuilding a Shattered Nation

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

As the cheers of the Grand Review crowds faded, the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers resumed life at Camp Brightwood, with many assuming that their days of wearing “Union Blue” were finally coming to an end. But that assumption proved to be an incorrect one when the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers received word that they were being reassigned. Ordered to pack their belongings in late May 1865, they would be heading back to America’s Deep South — this time to assist with Reconstruction duties in Georgia and South Carolina, beginning the first week in June.

Sources:

- “Assassination of President Abraham Lincoln.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online May 21, 2025.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Battleground National Cemetery: Battleround to Community — Brightwood Heritage Trail,” “Fort Stevens” and “Mayor Emery and the Union Army.” United States: Historical Marker Database, retrieved online May 20, 2025.

- “Battleground to Community: Brightwood Heritage Trail.” Washington, D.C.: Cultural Tourism DC, 2008.

- “Grand Military Review: Streets Crowded with Spectators: Sherman Greeted with Deafening Cheers.” Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Daily Post, May 25, 1865.

- “Grant” (television mini-series). New York, New York: History Channel Education, 2020.

- “Our Heroes! The Grand Review at Washington. Honor to the Brave. Immense Outpouring of the People. The Troops Reviewed by Gen. Grant.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Daily Telegraph, May 23, 1865.

- Pitman, Benn. The Assassination of President Abraham Lincoln and the Trial of the Conspirators. Cincinnati, Ohio and New York, New York: Moore, Wilstach & Boldwin, 1865.

- “Reconstruction: An Overview.” Washington, D.C.: American Battlefield Trust, November 28, 2023.

- “Review of the Armies; Propitious Weather and a Splendid Spectacle. Nearly a Hundred Thousand Veterans in the Lines.” New York, New York: The New York Times, May 24, 1865, front page.

- Rodrock, Rev. William D. C. Chaplain’s Reports (47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, 1865). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- “Serenade to General Grant” (performance for Lieutenant-General Ulysses S. Grant by the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers’ Regimental Band), in “Washington.” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Inquirer, May 22, 1865.

- Steers, Edward Jr. and Harold Holzer. The Lincoln Assassination Conspirators: Their Confinement and Execution, as Recorded in the Letterbook of John Frederick Hartranft. Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 2009.

- “The Final March: Grand Review of the Armies.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online May 20, 2025.

- “The Grand Review: A Grand Spectacle Witnessed.” Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: The Daily Post, May 24, 1865.

- “The Grand Review: Immense Crowds in Washington: Fine Appearance of the Troops: Their Enthusiastic Reception.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Daily Telegraph, May 24, 1865; and West Chester, Pennsylvania: The Record, May 17, 1865.

- “The Grand Review: The City Crowded with Visitors: Order of Corps, Divisions, Brigades and Regiments.” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Daily Constitutional Union, May 23, 1865.

- “The History of the Forty-Seventh Regt. P. V.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Lehigh Register, 20 July 1870.

- “The Lincoln Conspirators,” in “Ford’s Theatre.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online May 21, 2025.

You must be logged in to post a comment.