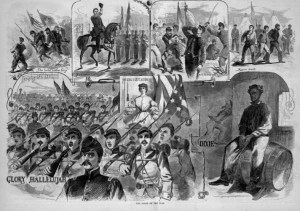

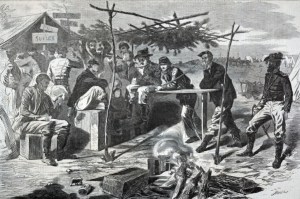

“The Songs of the War,” Homer Winslow (Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1861, public domain; click image to enlarge).

“Music has done its share, and more than its share, in winning this war.” — Major-General Philip H. Sheridan

“The Civil War played an instrumental role in the development of an American national identity,” according to historians at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. “Specifically for American folk music, the war inspired songwriting on both sides of the conflict, as amateurs and professionals wrote new, timely lyrics to old English, Scottish, and Irish ballads as well as original compositions.”

That new music, in turn, inspired one American artist, Winslow Homer, to capture the support he was witnessing and hearing for the United States government and its Union Army defenders during the mid-nineteenth century — support that was conveyed through the enthusiastic singing of pro-Union songs by soldiers, abolitionists and others who had dedicated themselves to the preservation of America’s Union and the eradication of the brutal practice of chattel slavery.

His sketch, “The Songs of the War,” which first appeared in print in the November 23, 1861 edition of Harper’s Weekly, featured seven of the most popular songs during the first year of the American Civil War: “The Bold Soldier Boy,” “Hail to the Chief,” “We’ll Be Free and Easy Still,” “Rogue’s March,” “Glory Hallelujah,” “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” and “Dixie.”

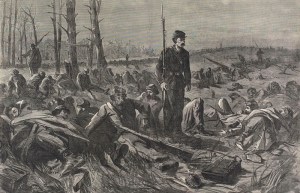

“The Bold Soldier Boy,” excerpt from the illustration, “The Songs of the War” (Winslow Homer, Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1861, public domain).

“The Bold Soldier Boy” was an old folk song that had been arranged by multiple composers in different ways throughout the nineteenth century prior to Homer’s first hearing of it. The specific variant of the tune that sparked Homer’s imagination as he drew the scene in the upper left corner of “The Songs of the War” was most likely the version that had been arranged by S. Lover and William Dressler. Published by Wm. Hall & Son of New York in 1851, that variant was one of the selections that was included in book one of Dressler’s Scraps of Melody for Young Pianists.

According to Dressler’s obituary in the The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, William Dressler had created this arrangement shortly after his emigration to the United States. A native of Nottingham, England, he was a son of the “court flutist to the King of Saxony” and an 1847 graduate of the Cologne Conservatory of Music in Germany, and had become well-known across the United States as an “organist and professor of music.”

“Hail to the Chief,” excerpt from “The Songs of the War” (Winslow Homer, Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1861).

“Hail to the Chief,” has since become familiar to generations of Americans as the triumphal tune performed by the United States Marine Band (“The President’s Own“) to herald the arrival of presidents of the United States at State of the Union addresses presented to the United States Congress, as well as other functions of the United States government. According to military music historian Jari Villaneuva, this particular piece of music “was already very popular when the Marine Band played it from a barge for the opening of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal on July 4, 1828, in the presence of President John Quincy Adams.”

During the American Civil War, “Hail to the Chief” was frequently performed by the bands of state and federal military regiments to announce the arrival of Union Army generals at special events, including the often well-attended public ceremonies when generals reviewed their troops. On September 17, 1861, for example, the Lancaster Intelligencer noted that Major-General George B. McClellan was greeted with a performance of “Hail to the Chief” as he arrived with a group of dignitaries at the camp of the Seventy-Ninth New York Volunteer Infantry on September 10.

“We’ll Be Free and Easy Still,” excerpt from “The Songs of the War” (Winslow Homer, Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1861, public domain).

With his scene, “We’ll Be Free and Easy Still,” Homer was referencing a song that had been promoted in broadside advertisements in London, England as far back as 1832. The song had been made popular thanks to its frequent performance in music halls across Great Britain during the 1840s.

According to historians at the U.S. Library of Congress, the melody was included as “Free and Easy,” in a medley of songs for cornet that was arranged by David L. Downing circa 1861 for concert band performance, and had been included in one of the manuscript books of the Manchester Cornet Band.

The source for the tune appears to have been the chorus of “‘Gay and Happy.’ Composed and sung by Miss Fanny Forrest (with unbounded applause) (Baltimore: Henry McCaffrey [1860])…. This version, or one similar to it, was almost certainly what Winslow Homer had in mind:

I’m the lad that’s free and easy,

Wheresoe’er I chance to be;

And I’ll do my best to please ye,

If you will but list to me.Chorus.–So let the world jog along as it will,

I’ll be free and easy still….

“We’ll Be Free and Easy Still” had become so popular by the mid-nineteenth century, in fact, that composer Stephen Foster referenced it in his 1866 song, “The Song of All Songs.

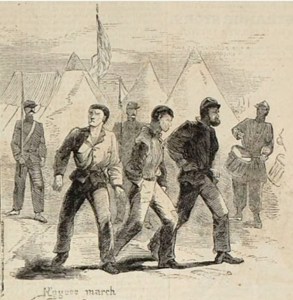

“Rogue’s March,” excerpt from “The Songs of the War” (Winslow Homer, Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1861, public domain).

Rogue’s March can be traced to an even earlier time — the mid-eighteenth century. It “was one of the most widespread and recognized melodies in martial repertory of the era,” according to Andrew Kuntz and Valerio Pelliccioni, creators of The Traditional Tune Archive. Also known as “Poor Old Robinson Crusoe,” this English march in G Major “was played in the British and American armies when military and civil offenders and other undesirable characters were drummed from camps and cantonments, sometimes with a halter about their necks, sometimes with the final disgrace of a farewell ritual kick from the regiment’s youngest drummer.” Also according to Kuntz and Pelliccioni:

[T]he actual ceremony consisted of as many drummers and fifers as possible (to make it the more impressive) [who] would parade the prisoner along the front of the regimental formation to this tune, and then to the entrance of the camp. The offender’s coat would be turned inside out as a sign of disgrace, and his hands were bound behind him…. The sentence would then be published in the local paper.

The fifers and drummers of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were actually called upon to play the “Rogue’s March” during the punishment and dismissal of one of their regiment’s own while the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were preparing for the regiment’s departure for America’s Deep South. According to regimental historian Lewis Schmidt, the public shaming of Private James C. Robinson of the 47th Pennsylvania’s Company I began at 10 a.m. on Monday, January 27, 1862, at the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, where the regiment was briefly stationed.

The regiment was formed and instructed by Lt. Col. Alexander ‘that we were about drumming out a member who had behaved himself unlike a soldier.’ …. The prisoner, Pvt. James C. Robinson of Company I, was a 36 year old miner from Allentown who had been ‘disgracefully discharged’ by order of the War Department. Pvt. Robinson was marched out with martial music playing and a guard of nine men, two men on each side and five behind him at charge bayonets. The music then struck up with ‘Robinson Crusoe’ as the procession was marched up and down in front of the regiment, and Pvt. Robinson was marched out of the yard.

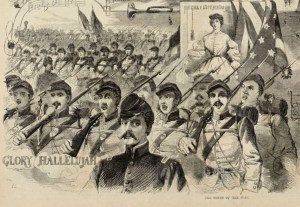

“Glory Hallelujah,” excerpt from “The Songs of the War” (Winslow Homer, Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1861, public domain).

“Glory Hallelujah” was almost certainly a reference to the chorus verse of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic,” the song which quickly became an anthem for the Union Army after the lyrics were written by abolitionist and suffragist Julia Ward Howe during November 1861. Set to the melody (and partially derived from the lyrics) of “John Brown’s Body,” a song sung often by Union soldiers during the earliest months of the war, Howe’s “Battle Hymn” was published in The Atlantic Monthly in February 1862 and remains one of the most popular patriotic songs in the United States.

The chorus of “Glory Hallelujah” was also then employed by Mrs. M. A. Kidder in an arrangement for piano by Augustus Cull of “Brave McClellan Is Our Leader Now, or Glory Hallelujah!“, which was published by Horace Waters of New York in 1862.

“The Girl I Left Behind Me,” excerpt from “The Songs of War” (Winslow Homer, Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1861, public domain).

Dating back to the 1700s, “The Girl I Left Behind Me” was derived from a popular Irish folk tune that reportedly served as the melody for multiple popular and military songs during the eighteenth and ninetenth centuries, according to Kuntz and Pelliccioni.

There are a few literary references to the song or melody. For example, “The Girl I Left Behind Me,” clearly a reference to the military use of the song, was the title of a chapter (XXX) in William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair (1848)…. The English novelist Thomas Hardy, himself an accordianist and fiddler, mentioned the tune in scene notes to The Dynasts….

James Fenimore Cooper mentions the tune in his novel of the sea, The Pilot (1824)….

“The Girl I Left Behind Me” has a long and illustrious history in America…. [I]t appears in Riley’s Flute Melodies, published in several volumes in New York beginning in 1814…. The melody appears in Bruce and Emmett’s Drummers’ and Fifers’ Guide, published in 1862 to help codify and train the hordes of new musicians needed for service in the Union Army early in the American Civil War. Therein it is remarked: “This air and (drum) beat is generally played at the departure of the soldiers from one city (or camp) to another….

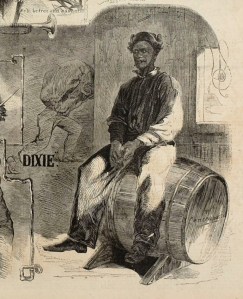

“Dixie,” excerpt from “The Songs of the War” (Winslow Homer, Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1861, public domain).

The final song that Homer chose to include in his pro-Union music montage, “Dixie” (an anthem of the Confederacy), might seem to have been an odd choice on his part, were in not for the way in which he chose to illustrate it. In the foreground, a free Black man looks thoughtfully off into the distance as he sits atop a barrel labeled with the word, “Contraband,” while a still-enslaved Black man struggles to move a heavy bale of cotton in the background, his body buckling from the burden he shoulders. That image was Homer’s powerful way of reminding Harper’s Weekly readers that, although some progress had already been made in the fight against the brutal practice of chattel slavery in parts of the United States, that fight was not yet won in “Dixie,” where many who were still enslaved continued to suffer greatly.

Sources:

- “Band Instruments,” in “Collection: Band Music from the Civil War Era.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- “Band Music,” in “Collection: Band Music from the Civil War Era.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- Baxter, John. “Free and Easy,” in “Folk Song and Music Hall.” Self-published, John Baxter, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- “Brave McClellan Is Our Leader Now, or Glory Hallelujah!”, in “New Music,” in “Local Items.” Brooklyn, New York: The Brooklyn Daily Times, 9 February 1862.

- “Brave McClellan Is Our Leader Now, or Glory Hallelujah!”, in “Notated Music.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- “Civil War Music: Dixie.” Washington, D.C.: American Battlefield Trust, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- “Free and Easy,” in “A Concert for Brass Band Voice and Piano,” in “Band Music from the Civil War Era.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- Homer, Winslow. “The Songs of the Civil War.” New York, New York: Harper’s Weekly, November 23, 1861.

- Kuntz, Andrew and Valerio Pelliccioni. “Rogue’s March.” Wappingers Falls, New York and Basiano, Italy: The Traditional Tune Archive, November 14, 2024.

- Kuntz, Andrew and Valerio Pelliccioni. “The Girl I Left Behind Me.” Wappingers Falls, New York and Basiano, Italy: The Traditional Tune Archive, December 22, 2024.

- McCollum, Sean. “Battle Hymn of the Republic: The Story Behind the Song.” Washington, D.C.: The Kennedy Center, September 17, 2019.

- “Pennsylvanians at Washington” (performance of “Hail to the Chief” to honor Major-General George B. McClellan). Lancaster, Pennsylvania: Lancaster Intelligencer, September 17, 1861.

- “Songs of the Civil War,” in “Smithsonian Folkways Recordings.” Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Institution, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- “The Bold Soldier Boy,” in “Notated Music.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- “The Bold Soldier Boy,” in Scraps of Melody for Young Pianists, in “New Music.” Cleveland Ohio: Morning Daily True Democrat, December 25, 1861.

- “The Civil War Bands,” in “Collection: Band Music from the Civil War Era.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- Thomas, Anne Elise. “Music of the Civil War.” Washington, D.C.: The Kennedy Center, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- Thompson, Beth. in “The Song of All Songs,” in “Beth’s Notes: Supporting and Inspiring Music Educators.” Self-published: Beth Thompson, retrieved online January 17, 2025.

- Villanueva, Jari. “Hail to the Chief.” Catonsville, Maryland: TapsBugler, January 17, 2025.

- “William Dressler” (obituary). Brooklyn, New York: The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, July 3, 1914.

You must be logged in to post a comment.