Major-General Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel, Commanding Officer, U.S. Department of the South and Tenth Corps, U.S. Army, circa 1862 (public domain).

On the heels of his army’s successful capture of Saint John’s Bluff, Florida and related events in early October 1862, Union Major-General Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel, commanding officer of the United States Army’s Department of the South, directed his senior staff and leadership of the U.S. Army’s Tenth Corps (X Corps) to intensify actions against the Confederate States Army and Navy in an effort to further disrupt the enemy’s ability to move troops and supplies throughout Florida, Georgia and South Carolina. As part of this directive, he engaged his senior officers in planning a new expedition — this time to Pocotaligo, South Carolina. According to Mitchel, preparations for that event began in earnest in mid-October, with an eye to the following objectives:

First, to make a complete reconnaissance of the Broad River and its three tributaries, Coosawhatchie, Tulifiny [sic], and Pocotaligo; second, to test practically the rapidity and safety with which a landing could be effected; third to learn the strength of the enemy on the main-land, now guarding the Charleston and Savannah Railroad; and fourth, to accomplish the destruction of so much of the road as could be effected in one day….

This 1856 map of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad shows the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina in relation to the town of Pocotaligo (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain; click to enlarge).

Mitchel then worked with his subordinate officers to determine how much of the U.S. Army’s Tenth Corps would take part in the expedition, assess the potential weak spots in his strategy and revise planning details to improve his soldiers’ likelihood of success:

The troops composing the expedition were the following: Forty-seventh Pennsylvania, 600 men; Fifty-fifth Pennsylvania, 400 men; Fourth New Hampshire, 600 men; Seventh Connecticut, 500 men; Third New Hampshire: 480 men; Sixth Connecticut, 500 men; Third Rhode Island, 300 men; Seventy-sixth Pennsylvania, 430 men; New York Mechanics and Engineers, 250 men; Forty-eighth New York, 300 men; one section of Hamilton’s battery and 40 men; one section of the First Regiment Artillery, Company M, battery and 40 men, and the First Massachusetts Cavalry, 100 men. Making an entire force of 4,500 men.

Every pains [sic] had been taken to secure as far as possible success for the expedition. Scouts and spies had been sent to the main-land to all the most important points between the Savannah River railroad bridge and the bridge across the Salkehatchie. A small party was sent out to cut, if possible, the telegraph wires. Scouts had been sent in boats up the tributaries of the Broad River. All the landings had been examined, and the depth of water in the several rivers ascertained as far as practicable. Two of our light-draught transports have been converted into formidable gunboats and are now heavily armed, to wit, The Planter and the George Washington. By my orders the New York Mechanics and Engineers, Colonel Serrell, had constructed two very large flat-boats, or scows, each capable of transporting half a battery of artillery, exclusive of the caissons, with the horses. They were provided with hinged aprons, to facilitate the landing not only of artillery but of troops from the transports.

Owing to an accident which occurred to the transport Cosmopolitan during the expedition to the Saint John’s River I found myself deficient in transportation, and applied to the commanding officer, Commodore Godon, of the South Atlantic Blockading Squadron, who promptly placed under my orders a number of light-draught gunboats for the double purpose of transportation and military protection.

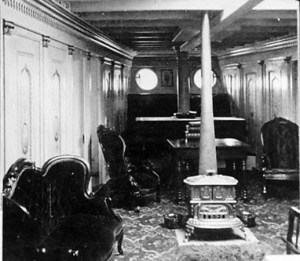

The after cabin inside of the U.S. Steamer Ben Deford, c. 1860s (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As planning progressed, details were firmed up regarding the Union Navy’s anticipated support. According to Mitchel:

On the evening of the 21st, under the command of Captain Steedman, U.S. Navy, the gunboats and transports were arranged in the following order for sailing: The Paul Jones, Captain Steedman, without troops; the Ben De Ford, Conemaugh, Wissahickon, Boston, Patroon, Darlington, steam-tug Relief, with schooner in tow; Marblehead, Vixen, Flora, Water Witch, George Washington, and Planter. The flat-boats, with artillery, were towed by the Ben De Ford and Boston. The best negro pilots which could be found were placed on the principal vessels, as well as signal officers, for the purpose of intercommunication. The night proved to be smoky and hazy, which produced some confusion in the sailing of the vessels, as signal lights could not be seen by those most remote from the leading ship. The larger vessels, however, got under way about 12 o’clock at night.

Union Army map, Pocotaligo-Coosawhatchie Expedition, 21-23 October 1862 (public domain; click to enlarge).

Mitchel and his leadership team also worked out the details of the expedition’s landing and debarkation plans, decided upon the weaponry they would need to disrupt and permanently disable the railroad tracks and the bridge at Pocotaligo and identified other possible actions to be undertaken by the expeditionary force:

After a careful examination of the map I ordered a landing to be effected at the mouth of the Pocotaligo River, at a place known as Mackay’s Point. This is really a narrow neck of land made by the Broad River and the Pocotaligo, in both of which rivers gunboats could lie and furnish a perfect protection for the debarkation and embarkation of the troops. There is a good country road leading from the Point to the old town of Pocotaligo, then entering a turnpike, which leads from the town of Coosawhatchie to the principal ferry on the Salkehatchie River. The distance to the railroad was only about 7 or 8 miles, thus rendering it possible to effect a landing, cut the railroad and telegraph wires, and return to the boats in the same day. I saw that it would be impossible for the troops to be attacked by the enemy either in flank or rear, as the two flanks were protected by the Pocotaligo River on the one hand and by the Broad and by the Tulifiny [sic, Tulifinny], its tributary, on the other. Presuming that the enemy would make his principal defense at or near Pocotaligo, I directed that a detachment of the Forty-eighth New York, under command of Colonel Barton, with the armed transport Planter, accompanied by one or two light-draught gunboats, should ascend the Coosawhatchie River, for the purpose of making a diversion, and in case no considerable force of the enemy was met, to destroy the railroad at and near the town of Coosawhatchie.

In addition to our land forces we were furnished by the Navy with several transports, armed with howitzers, three of which were landed with the artillery, and thus gave us a battery of seven pieces. All the troops were furnished with 100 rounds of ammunition. Two light ambulances and one wagon, with its team, accompanied the expedition.

The Integral Role of the 47th Pennsylvania

Design of the U.S. Army’s insignia for the Tenth (X) Army Corps, which would have been sewn onto uniforms of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry and displayed on a flag carried by the regiment during the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina on 22 October 1862 (public domain).

The Union Army regiments selected for participation in the Pocotaligo expedition were part of the U.S. Army’s Tenth Corps (X Corps), which was part of the U.S. Army’s larger Department of the South, which was headquartered at Hilton Head, South Carolina and oversaw Union military operations in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina during this time. Established on 13 September 1862, the Tenth Corps served under the command of Union Major-General Ormsby MacKnight Mitchel from the time of its founding until his death from yellow fever on 30 October of that same year. It was then placed under the command of Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan, who had also assumed command of the U.S. Army’s Department of the South, a position he held until 21 January 1863.

Among the regiments attached to the U.S. Army’s Tenth Corps in the U.S. Department of the South during fall of 1862 was the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, which would later make history as the only regiment from Pennsylvania to participate in the Union’s 1864 Red River Campaign across Louisiana. The 47th Pennsylvania, which had been founded on 5 August 1861 by Colonel Tilghman H. Good, remained under Colonel Good’s command. Regimental operations were also overseen by Good’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander.

As preparations continued to be refined, Brigadier-General Brannan determined, in his new role as commanding officer of the expedition, that he would need one of his subordinate officers to take his place on the field as the expedition began. He chose Colonel Good of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, who would go on to become a three-time mayor of Allentown, Pennsylvania after the war. Good then placed Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander in direct command of the 47th Pennsylvania. A New Hampshire native, Alexander had served as captain of the Reading Artillerists in Berks County, Pennsylvania prior to the war; post-war, he founded G. W. Alexander & Sons, a renowned hat manufacturing company that was based in West Reading.

What all of those Union Army infantrymen did not know at the time they boarded their respective transport ships on 21 October 1862 was that they would soon been engaged in combat so intense that the day would come to be described in history books more than a century later as the Second Battle of Pocotaligo (or the Battle of Yemassee, due to its proximity to the town of Yemassee, South Carolina).

This encounter between the Union and Confederate armies would unfold on 22 October 1862 between Savannah, Georgia and Charleston, South Carolina on the banks of the Pocotaligo River in northern Beaufort County, South Carolina.

Next: The Second Battle of Pocotaligo

Sources:

- “General Orders, Hdqrs., Department of the South, Numbers 40, Hilton Head, Port Royal, S. C., September 17, 1862” (announcement by Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel that he has assumed command of the newly formed Department of the South), in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Prepared Under the Direction of the Secretary of War, By Lieut. Col. Robert N. Scott, Third U.S. Artillery, and Published Pursuant to Act of Congress Approved June 16, 1880, Series I, Vol. XIV, Serial 20, p. 382. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885.

- “Report of Maj. Gen. Ormsby M. Mitchel, U.S. Army, commanding Department of the South and Return of Casualties in the Union forces in the skirmish at Coosawhatchie and engagements at the Caston and Frampton Plantations, near Pocotaligo, S.C., October 22, 1862,” in The War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies. Prepared Under the Direction of the Secretary of War, By Lieut. Col. Robert N. Scott, Third U.S. Artillery, and Published Pursuant to Act of Congress Approved June 16, 1880, Series I, Vol. XIV. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1885.

You must be logged in to post a comment.