First State Color, 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Presented to the Regiment by Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Curtin on 20 September 1861. Retired 11 May 1865. Source: Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee (1985.057, State Color, Evans and Hassall, v1p126).

As the days of September 1861 rolled away and summer turned to fall, the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, which had been founded by Colonel Tilghman H. Good on 5 August 1861, and had been trained in Hardee’s Light Infantry Tactics as its men mustered in by company at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg from mid-August through mid-September, was finally given its first official assignment — to defend its nation’s capital, which had been threatened with invasion by troops of the Confederate States Army.

Roughly seventy percent of the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry hailed from the Keystone State’s Lehigh Valley, including the cities of Allentown, Bethlehem and Easton and surrounding communities in Lehigh and Northampton counties. Company C, which had been formed primarily from the men of Northumberland County and was led by Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, was more commonly known as the “Sunbury Guards.” Companies D and H were staffed largely by men from Perry County. Company K was formed with the intent of creating an “all German” company comprised of German-Americans and German immigrants. In actuality, the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were men of German descent — a noteworthy fact when considering the significant role played by German immigrants and German-Americans prior to, during, and after the American Civil War. Curriculum developers at Boston’s WGBH Educational Foundation, which produced the 1998 PBS television series, Africans in America, note that:

“As early as 1688, four German Quakers in Germantown near Philadelphia protested slavery in a resolution that condemned the “traffic of Men-body.” By the 1770s, abolitionism was a full-scale movement in Pennsylvania. Led by such Quaker activists as Anthony Benezet and John Woolman, many Philadelphia slaveholders of all denominations had begun bowing to pressure to emancipate their slaves on religious, moral, and economic grounds.

In April 1775, Benezet called the first meeting of the Society for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully held in Bondage at the Rising Sun Tavern. Thomas Paine was among the ten white Philadelphians who attended; seven of the group were Quakers. Often referred to as the Abolition Society, the group focused on intervention in the cases of blacks and Indians who claimed to have been illegally enslaved. Of the twenty-four men who attended the four meetings held before the Society disbanded, seventeen were Quakers.

Six of these original members were among the largely Quaker group of eighteen Philadelphians that reorganized in February 1784 as the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and for the Relief of Free Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage (commonly referred to as the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, or PAS). Although still occupied with litigation on behalf of blacks who were illegally enslaved under existing laws, the new name reflected the Society’s growing emphasis on abolition as a goal. Within two years, the group had grown to 82 members and inspired the establishment of anti-slavery organizations in other cities.

PAS reorganized once again in 1787. While previously, artisans and shopkeepers had been the core of the organization, PAS broadened its membership to include such prominent figures as Benjamin Franklin and Benjamin Rush, who helped write the Society’s new constitution. PAS became much more aggressive in its strategy of litigation on behalf of free blacks, and attempted to work more closely with the Free African Society in a wide range of social, political and educational activity.

In 1787, PAS organized local efforts to support the crusade to ban the international slave trade and petitioned the Constitutional Convention to institute a ban. The following year, in collaboration with the Society of Friends, PAS successfully petitioned the Pennsylvania legislature to amend the gradual abolition act of 1780. As a result of the 2000-signature petition and other lobbying efforts, the legislature prohibited the transportation of slave children or pregnant women out of Pennsylvania, as well as the building, outfitting or sending of slave ships from Philadelphia. The amended act imposed heavier fines for slave kidnapping, and made it illegal to separate slave families by more than ten miles.”

Although the Pennsylvania Abolition Society’s influence had begun to wane by the early 1800s, men and women of German descent helped to reinvigorate support for the abolition of slavery in the lead-up to and during the Civil War. According to Kenneth Barkin, professor emeritus of history at the University of California, Riverside, “it is increasingly evident that German immigrant opposition to slavery was so pervasive that it may have been a crucial, albeit, ignored factor in the victory of Union forces.”

“Of the 1.3 million German immigrants in the United States before 1860, approximately 200,000 either volunteered for or were drafted into the Union Army. They produced a considerably higher percentage of Union soldiers per hundred thousand immigrants in the U.S. population than either the British or the Irish. About 24 percent of Union troops were born outside of the United States, and 10 percent of all Union soldiers were of German origin. There were several battalions with German soldiers and officers in which the German language was used for communication.”

In the case of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry, many of the men who were of German heritage and their families still spoke German or “Pennsylvania Dutch” at their homes and churches more than a century after their ancestors emigrated from Germany in search of religious or political freedom.

The 47th Pennsylvania was also noteworthy because it attracted males of diverse ages. Its youngest member was John Boulton Young, a thirteen-year-old drummer boy from Sunbury, Pennsylvania; its oldest was Benjamin Walls, a sixty-five-year-old, financially successful farmer from Juniata County who would, at the age of sixty-eight, attempt to re-enlist after being seriously wounded while protecting the American flag in combat. They and their comrades were initially led by Colonel Tilghman Good, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, and Major William H. Gausler.

Thomas Coates, “Father of Band Music in America,” led the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band from August 1861 to September 1862 (public domain).

On Friday the 13th, there were frequent bouts of inspiration among Harrisburg residents, rather than of superstitious worry, as three thousand men from the 47th Pennsylvania and other volunteer regiments from the Keystone State marched in an impromptu parade from Camp Curtin through the city’s main streets.

The next day, members of the 47th Pennsylvania marched forth again — this time to welcome the arrival of their Regimental Band, which was led by the “Father of Band Music in America,” Professor Thomas Coates, and was comprised primarily of musicians from the Easton-based ensemble known as Pomp’s Cornet Band, as well as members of the Allentown Band. Later that evening, the band performed for Pennsylvania Governor Andrew Gregg Curtin.

With the majority of the regiment’s officers and enlisted men mustered in by 19 September 1861, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was ordered to head south for Washington, D.C.

A Journey of Heroes Begins

President Abraham Lincoln’s funeral train passes through the train station in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania on 22 April 1865 (public domain).

Their epic journey began on 20 September 1861. Directed to begin packing at 5:00 a.m. so that they would be ready for a 7:00 a.m. departure by train, the men of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry pulled their gear together and assembled in formation at Camp Curtin. They were then presented with the Pennsylvania State Battle Flag (shown at the top of this article). Also known as the First State Color, it had “a field of 34 white stars, one for each state both north and south, on a blue background in the upper left corner in the shape of a rectangle covering approximately 19% of the flag’s total area, with 17 stars above and below the state emblem, which consisted of two white horses, eagle, seal and inscription,” according to regimental historian Lewis Schmidt. “The remainder of the flag was composed of 7 red and 6 white alternating horizontal stripes, and the whole was fringed with gold braid. The unit designation was painted in gold on the center red stripe to the right of the bottom of the blue field. As battle citations were awarded each unit, they would be painted on the red stripes in gold lettering.”

This flag would ultimately be carried by regimental color-bearers between the fall of 1861 and 11 May 1865 into Confederate States of America-held territories of the United States, as well as throughout multiple U.S. territories that were recaptured by Union troops, and would also serve as a rallying point during the intense, smoke-filled battles fought by the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry in South Carolina, Louisiana, and Virginia in 1862 and 1864.

Marched to the train station in Harrisburg, they boarded cattle and hog cars on a Northern Central Railway train, and then did what military men have done throughout the ages. They waited — and waited. By the time of their 1:30 p.m. departure, a crowd “had gathered and lined both sides of the track, all the way from the depot to the other side of the bridge which crosses the Susquehanna River,” according to Schmidt. “Everyone was cheering, flags were flying, and the men were hanging from the cars, all in a great state of excitement. Many railroad friends of the Easton contingent that had been part of the 1st Regiment during earlier service, turned out to see them off with their new unit, having transported them to the seat of war on earlier occasions.”

Traveling by way of York, Pennsylvania, they finally reached the Bolton Depot in Baltimore, Maryland, where they disembarked, refilled their canteens with water, lined up behind their Regimental Band, and marched with their loaded rifles across the city to the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Station. Once there, they clambered aboard “glorious to tell, real genuine passenger cars” and departed for Washington, D.C., according to Captain Gobin, who added that the “lateness of the hour did not prevent the appearance, at a great many windows, of white robed fair ones, who had evidently risen from their beds to greet and cheer us as we passed.”

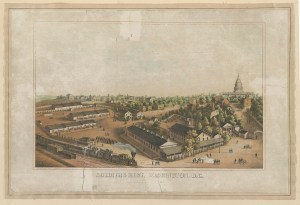

Soldier’s Rest, Washington, D.C., circa 1860s (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Just outside of Baltimore, according to Schmidt, “the troop train had to ‘switch off’ for a short time, as the regular passenger train passed.” Consequently, the 47th Pennsylvanians did not arrive in the nation’s capital until 9:00 a.m. on 21 September. Disembarking after the train came to a stop, they were granted a brief respite at the Soldier’s Rest there, according to C Company Musician Henry Wharton, who later penned a recap of their travels for his hometown newspaper, the Sunbury American:

“After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.”

Gobin, who was Wharton’s direct superior, added that, when they arrived at the Soldier’s Rest, “we found the Union Relief Association had provided ice water in abundance for us, while hot coffee could be obtained for three cents a cup. I indulged in several of the latter.” Schmidt later uncovered these additional details about their brief period of respite:

“At 9 AM, the regiment arrived in Washington and Col. Good left to find a place for the men to camp and get some rest, while Lt. Col. Alexander busied himself seeing to the problem of procuring some cooked rations for the troops. The first building that they saw when they arrived was a very large structure near the railroad which displayed a sign with prominent letters that read ‘The Soldier’s Rest’, a place they intended to head for at the first opportunity. Lt. Col. Alexander returned shortly thereafter and instructed the Captains to take their companies, two at a time, to another building conveniently in view in the distance, and identified by its large sign with letters in bold relief advertising ‘Soldier’s Retreat’, where the men were served cooked beef, bread and coffee. The soldiers satisfied their hunger with this excellent meal, and ‘partook that which sticks to your ribs’, before settling down and enjoying a few hours rest and free [time], after which they washed up and had their pictures taken.”

Afterward, according to Wharton, they “were ordered into line and marched, about three miles” to “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown — just two miles from the White House.

“So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.”

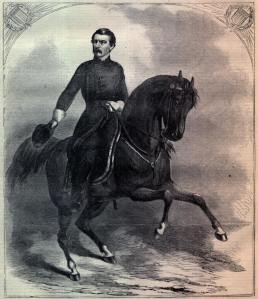

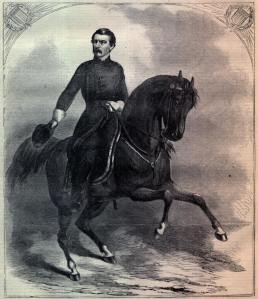

Union General George B. McClellan on Horseback (Harper’s Weekly, January 1862, public domain).

The length of that march was, in fact, closer to four miles, and was “considerably more difficult,” according to Schmidt, “since the men had not had any sleep the night before and they were marching in the warmest part of the day with a strong, bright sun in their faces the whole way.” That march also turned out to be a noteworthy one for an entirely different reason, according to Wharton:

“We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering [sic] they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.”

The weary 47th Pennsylvanians finally arrived at Camp Kalorama around 5:00 p.m. on 21 September, and immediately began to erect their white soldiers’ tents — an activity they continued to engage in even as the region’s rainy weather began to increase in intensity.

The U.S. Capitol, under construction at the time of President Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration (shown here), was still not finished when the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Washington, D.C. in September 1861 (public domain).

The next day, as Wharton was penning his 22 September recap to the Sunbury American, he described Colonel Tilghman Good as “an excellent man and a splendid soldier” and “a man of very few words” who continually attend[ed] to his duties and the wants of the Regiment,” and added that C Company’s William Hendricks had been promoted to the rank of regimental sergeant-major. “He made his first appearance at guard mounting this morning; he looked well, done up his duties admirably, and, in time, will make an excellent officer.” Gobin observed that their new home was “a very fine location for a camp…. Good water is handy, while Rock Creek, which skirts one side of us, affords an excellent place for washing and bathing.”

Within short order, several 47th Pennsylvanians were given passes to the city, including members of Company D who “climbed to the top of the unfinished Capitol,” and B Company’s Corporal Henry Storch and Private Luther Mennig, who were sent to the Washington Arsenal on regimental business. On 24 September 1861, the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry finally became part of the Union Army when its men were officially mustered into federal service. Members of the regiment dressed in the standard dark blue wool uniforms worn by the regular troops of the U.S. Army.

Three days later, the regiment was attached to the Army of the Potomac, and assigned to Brigadier-General Isaac Stevens’ 3rd Brigade, which also included the 33rd, 49th and 79th New York regiments. By that afternoon, the 47th Pennsylvania was on the move again, ordered onward by Brigadier-General Silas Casey.

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

Marching behind their Regimental Band, the Mississippi rifle-armed 47th Pennsylvania infantrymen reached Camp Lyon, Maryland on the Potomac River’s eastern shore. At 5:00 p.m., they joined the 46th Pennsylvania in moving double-quick (onehundred and sixty-five steps per minute using thirty-three-inch steps) across the “Chain Bridge” marked on federal maps, and continued on for roughly another mile before being ordered to make camp.

The next morning, they broke camp and moved again. Marching toward Falls Church, Virginia, they trudged into Camp Advance around dusk. There, about two miles from the bridge they had crossed a day earlier, they re-pitched their tents in a deep ravine near a new federal fort under construction (Fort Ethan Allen). They had completed a roughly eight-mile trek, and were situated fairly close to Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith’s headquarters. Under Smith’s leadership, their regiment and brigade would help to defend the nation’s capital from the time of their September arrival through late January of 1862 when the men of the 47th Pennsylvania would be shipped south.

Once again, 47th Pennsylvanians took pen to paper to recap their regiment’s activities, including Privates George Washington Hahn, David Huber and Frederick Scott of E Company who sent this letter to the editor of the Easton Express:

“Most likely you have already published the letter from the headquarters of the company, but it may also be interesting to some of your readers to hear from the boys.

We left Harrisburg at 1-1/2 p.m. on Friday last, and after a ride of about twenty-four hours in those delightful cattle cars, we came in sight of the Capitol of the U.S. with colors flying and the band playing and everyone in the best of spirits. After waiting a few minutes, we were provided with an excellent dinner of bread, beef and coffee, and then proceeded to Camp Kalorama, near Georgetown Heights and about three miles from Washington. We have one of the best camps in the Union; plenty of shade trees, water and food at present; we have had no ‘Hardees’ [hardtack] yet in this camp, but no doubt we will have them in abundance by and by. But we can cook them in so many different ways, they are better than beef. We soak them overnight, fry them for breakfast, stew them for dinner, and warm them over for supper. Who wouldn’t be a soldier and get such good living free gratis?

We are all happy boys. The way we pass our time in the evening is as follows: first, after supper, we have a good Union song, then we read, write, crack jokes and sing again. We are ‘gay and happy’ and always shall be while the stars and stripes float over us.

We have one of the best regiments we have yet seen, and no doubt in a few months, it will be the crack regiment of the army. We have a noble Colonel and an excellent Band, and the company officers throughout are well drilled for their positions. Our boys are well and contented; satisfied with their clothing, satisfied with their rations, and more than all satisfied with their officers, from Captain to the 8th Corporal. Our boys will stand by the Captain till the last man falls. We had the pleasure this morning of meeting an old Eastonian, Major Baldy. He looks well and hearty and says he is ready for action. His men are in the rifle pits every night and think nothing of facing the enemy.

This morning we took a French pass [leave without authorization] and visited Georgetown Heights; we stood on top of the reservoir and from there had a fine view of the Federal forts and forces on the other side of the Potomac. It looks impossible for an enemy to enter Washington, so strongly fortified is every hill and the camps connect for miles along the river. We saw General McClellan and Professor Lowe taking a view of the Confederate army from the balloon. The rebels are now only four miles from here. But we are afraid we have taken too much of your room. You may expect to hear from us again soon.”

Company C Musician Henry Wharton then noted via this 29 September letter to the Sunbury American that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

“On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment.”

According to G Company Private George Xander, after their initial arrival at Camp Advance/Fort Ethan Allen, the 47th Pennsylvanians immediately began building “defensive works” that “were thrown up with logs, in front of which a ditch eight feet wide and eight feet deep was dug. A powder magazine was also built.” On 28 September, the regiment was ordered to relocate yet again. After marching two more miles, they re-pitched their tents along a hill at the back of the fort, becoming part of the 4th Provisional Brigade, along with the men from Colonel Cosgrove’s 27th Indiana Volunteers, Colonel Leasure’s Roundheads, Colonel McKnight’s Wildcats, and Colonel Robinson’s 1st Michigan Volunteers.

The military action described by Wharton above in which “our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge” actually began at 10:00 p.m. on Saturday, 28 September in response to intelligence received by senior Union Army officials that Fort Ethan Allen was likely to be attacked by Confederate forces that night. After making their way inside the fort at 10:30 p.m., the 47th Pennsylvanians formed battle lines “against the breastworks where they remained until 2 AM, when they were relieved by the 33rd New York Regiment and told to rest and sleep on their arms,” according to Schmidt. Around 4:00 a.m., they were then “ordered to march ‘double-quick for about three miles to Vandersburg Farm, where encountering no officers with instructions, Col. Good decided to advance another mile…. Here he found Gen. Smith who ordered the 47th into position in reserve. Many ambulances were coming up the road with the dead and wounded, and there were dead horses and broken gun carriages lying all about. It was reported that there were about 17 killed and 25 wounded.”

Although the 47th Pennsylvania was later reported to have been involved in the fighting, they were not. They had narrowly missed being ensnared in a “friendly fire” incident between the 69th and 71st Pennsylvania Volunteers, and instead had been ordered to return to their campsite on the hill after having completed their guard duties inside the fort. Finally able to enjoy a hearty breakfast that Sunday morning, the regiment then participated in the Sunday religious services which were being presented by Chaplain Rizer of the 79th New York Highlanders. The sermon was delivered by Rizer in German out of respect for the significant number of men in the 47th Pennsylvania who were German immigrants or were German-Americans who spoke “Pennsylvania Dutch.”

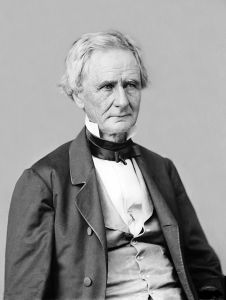

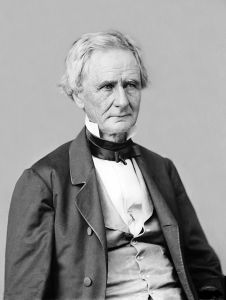

Simon Cameron, President Lincoln’s first Secretary of War, shown between 1860 and 1870 (public domain).

That evening of Sunday, 29 September, Simon Cameron, a native of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania who was serving as President Lincoln’s Secretary of War, officially welcomed the 47th Pennsylvania Infantry to Washington.

The month then closed with the men of 47th’s B and D Companies marching four miles away from the camp to perform a 48-hour stint of picket duty, beginning on 30 September 1861.

Exactly two months later, the sentiments of Civil War-era soldiers regarding their assignment to picket duty was eloquently evoked by a 30-something, female poet and short story writer in the “The Picket Guard.” Penned by Ethel Lynn Beers, the poem was initially published in the 30 November 1861 edition of Harper’s Weekly. It was then later set to music, and became more commonly known as “All Quiet Along the Potomac To-night”:

“ALL quiet along the Potomac to-night!”

Except here and there a stray picket

Is shot, as he walks on his beat, to and fro,

By a rifleman hid in the thicket.

‘Tis nothing! a private or two, now and then,

Will not count in the news of the battle;

Not an officer lost, only one of the men,

Moaning out, all alone, the death rattle.

All quiet along the Potomac to-night!

Where the soldiers lie peacefully dreaming;

And their tents in the rays of the clear autumn moon,

And the light of the camp-fires are gleaming.

A tremulous sigh, as the gentle night-wind

Through the forest leaves softly is creeping;

While stars up above, with their glittering eyes,

Keep guard o’er the army sleeping.

There’s only the sound of the lone sentry’s tread

As he tramps from the rock to the fountain,

And he thinks of the two in the low trundle-bed,

Far away in the cot on the mountain.

His musket falls slack; his face, dark and grim,

Grows gentle with memories tender,

As he mutters a prayer for the children asleep,

For their mother—”may Heaven defend her!”

The moon seems to shine just as brightly as then—

That night when the love, yet unspoken,

Leaped up to his lips, when low, murmured vows

Were pledged to be ever unbroken.

Then drawing his sleeve roughly over his eyes,

He dashes off tears that are welling,

And gathers his gun closer up to his breast

As if to keep down the heart’s swelling.

He passes the fountain, the blasted pine-tree,

And his footstep is lagging and weary;

Yet onward he goes, through the broad belt of light,

Toward the shades of the forest so dreary.

Hark! was it the night-wind that rustled the leaves?

Was it moonlight so wondrously flashing?

It looked like a rifle: “Ha! Mary, good-by!”

And the life-blood is ebbing and plashing.

“All quiet along the Potomac to-night!”

No sound save the rush of the river,

While soft falls the dew on the face of the dead,

The picket’s off duty forever!

Sources:

- Barkin, Kenneth. “Ordinary Germans, Slavery, and the U.S. Civil War,” in “Essay Reviews,” in The Journal of African American History, Vol. 93, No. 1, Winter 2008, pp. 70-79. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press (published for the Association for the Study of African American and History), 2008.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, Prepared in Compliance with Acts of the Legislature, vol. 1, 1150-1190. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Beers, Ethel Lynn. “The Picket Guard.” New York, New York: Harper’s Weekly, 30 November 1861.

- Egle, William H. Life and Times of Andrew Gregg Curtin, pp. 127, 250. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: The Thompson Publishing Co., 1896.

- “47th Infantry, First State Color,” in “Pennsylvania Civil War Battle Flags.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania Capitol Preservation Committee.

- “Founding of the Pennsylvania Abolition Society,” in Africans in America. Boston, Massachusetts: WGBH Educational Foundation, 1998.

- Hahn, George Washington, David Huber and Frederick Scott. Letter from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers. Easton, Pennsylvania: Easton Daily Evening Express, September 1861.

- Hardee, William Joseph. Hardee’s Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics. Memphis, Tennessee: E.C. Kirk & Co., 1861.

- Henry, Matthew Schropp. History of the Lehigh Valley, Containing a Copious Selection of the Most Interesting Facts, Traditions, Biographical Sketches, Anecdotes, etc., etc., Relating to Its History and Antiquities, pp. 141-143. Easton, Pennsylvania: Bixler & Corwin, 1860.

- “Letter from the Secretary of War, Transmitting the report of Major General George B. McClellan upon the organization of the Army of the Potomac, and its campaigns in Virginia and Maryland, from July 26, 1861, to November 7, 1862.” Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office (Ex. Doc. No. 15 produced for the 38th Congress, 1st Session, U.S. House of Representatives), 1864.

- Mathews, Alfred and Austin N. Hungerford. History of the Counties of Lehigh and Carbon, in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Everts & Richards, 1884.

- Newman, Richard S. “The PAS and American Abolitionism: A Century of Activism from the American Revolutionary Era to the Civil War,” in “Pennsylvania Abolition Society Papers,” in “History Online: Digital History Projects.” Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Historical Society of Pennsylvania, retrieved online 28 August 2019.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- Wharton, Henry. Letters from the Sunbury Guards. Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 1861-1862.

You must be logged in to post a comment.