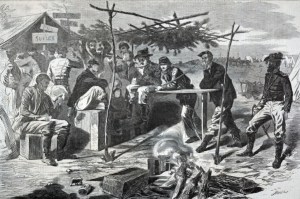

It is evening on the camp ground, and the fading sunlight gleams,

Over hill tops, into valleys and adown the winding streams;

Weary drill at last is ended, and the soldiers gather in

To the music of the fifers and the sweet-toned violin.

Noble sons of patriot fathers, loving freedom most of all,

Dreading more the tyrant’s sceptre than the rifle’s deadly ball;

Each within his homely quarters, on his hard unpillowed bed,

Takes the uninviting supper, by no loving mother spread.

Not for them the winter fire where the family group is found,

Pleasant converse, peals of laughter, merry jestings circling round;

Where the mother piles her knitting, and the sisters read or sew,

And the father paints in language, “miracles of long ago.”

Not for them! yet through their changes, Memory keeps her taper bright,

Lighting up the streams of day-time, and the visions of the night;

Hearts that know no selfish terror, through their tender pulses send,

Throbs of strong magnetic feeling, to the parent or the friend.

One is writing to his mother, and his thoughtful eye grows dim,

With the memory of her kindness, and her loving care for him;

Patient of his youthful follies, quick to lead and slow to blame,

Rising with his rising honor, sinking if he sink to shame.

Well she knows her pillowed slumbers are not as they were of old;

Well he knows the grief and terror that her pen hath never told;

And he sees the dark brown tresses, growing whiter day by day,

Since her country’s tocsin sounded, and she gave her all away.

And another reads the message that a Father’s hand hath sent,

Strong in courage, wise in council, glowing with a high intent;

“All his prayers go forth to bless him–he has been his pride and joy,

And the hopes of past and present crowd around his darling boy.”

With a quivering lip he folds it, but his keen and steady eye,

Speaks the strong, unshaken courage, that shall conquer or shall die;

Gentle words a wife has written, there the husband reads to-night,

And his manly tears are hidden in the fading winter light.

Then he folds his daughter’s billet in a warm and close embrace,

Her’s, who holds the prisoned sunbeams of eight summers in her face;

Ah! he cares not for the blunders, through each blurred and crooked line,

All the glances of her blue eyes and her bady graces shine.

Needs must tremble they who called him from such pleasures to the strife,

He will keep his vow of vengeance at the peril of his life;

Where the sunbeams linger longest, heeding not the frosty air,

With his pale young forehead shaded, sits another reading there.

One who loved him like the poets, shared this in the days gone by,

And each line looks kindly at him through that sister’s speaking eye.

“Sits she in the dear old Study, reading what I read to-night,

Tracing out the rhythmic numbers, in the flashing crimson light;

Or, perchance, the lamps are lighted, and she pens the gentle line

That gives olden warmth and comfort to this stranger life of mine.”

There a young man holds a locket, gazing on a face so dear,

That the past becomes the present, and the far away the near;

Over streams, and hills and vallies, he is standing by her side,

And her dark brown eyes are liquid with the gush of love and pride.

Sweeter than the sounds of summer is the language that she speaks;

Fairer than June’s fairest blossoms, are the roses on her cheeks,

And he feels to-day more worthy plighted heart and hand,

Than when peace and smiling plenty blessed his sorrowing Fatherland.

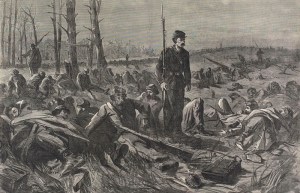

Breaking on the evening’s bustle calls the drum to muster roll,

And the soldier’s sterner duties shade the fancies of his soul.

Turning to their straw and blankets, quiet slumbers close them round;

Nothing but the sentry’s pacing breaks the silence of the ground,

And the stars look kindly on them from the blue etherial sea,

Leading on the Hosts of Freemen through the gates of victory.

MELROSE

Source:

“Select Poetry [from the West Chester (Pa) Times].” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Sunbury American, 28 December 1861.

You must be logged in to post a comment.