“[T]he impact and meaning of the war’s casualties were not simply a consequence of scale, of the sheer numbers of Union and Confederate soldiers who died. Death’s significance for the Civil War generation derived as well from the way it violated prevailing assumptions about life’s proper end — about who should die, when and where, and under what circumstances.”

— Drew Gilpin Faust, Ph.D., President Emeritus and the Arthur Kingsley Porter University Professor, Harvard University and author, This Republic of Suffering: Death and the Civil War

Less than a month after leaving the great Keystone State for the Eastern Theater of America’s shattering Civil War, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry encountered their most fearsome foe — the one they would consistently find the most difficult to defeat throughout the long war — disease.

It was an enemy, in fact, that turned out to be the deadliest not just for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, but for the entire Union Army as it fought to preserve the nation’s Union while ending the practice of slavery across the United States. Per The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History, sixty-two percent of all Union soldiers who died during the American Civil War were felled by disease, rather than by the shrapnel-spewing blasts of Confederate cannon or the accurately targeted minié balls of CSA rifles.

Surprising as this may seem to this century’s students of American History, it shouldn’t be, according to infectious disease specialist Jeffrey S. Sartin, M.D.:

“The American Civil War represents a landmark in military and medical history as the last large-scale conflict fought without knowledge of the germ theory of disease. Unsound hygiene, dietary deficiencies, and battle wounds set the stage for epidemic infection, while inadequate information about disease causation greatly hampered disease prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. Pneumonia, typhoid, diarrhea/dysentery, and malaria were the predominant illnesses. Altogether, two-thirds of the approximately 660,000 deaths of soldiers were caused by uncontrolled infectious diseases, and epidemics played a major role in halting several major campaigns. These delays, coming at a crucial point early in the war, prolonged the fighting by as much as 2 years.”

With respect to the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, the two diseases which wreaked such devastating havoc early on were Variola (smallpox) and typhoid fever.

Variola

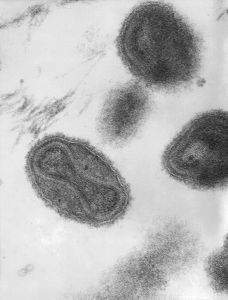

A transmission electron micrograph of an 1849 strain of Variola shows several smallpox virions. Note the “dumbbell-shaped” structure. Located inside the virion, this is the viral core, and contains the DNA of the virus (Temple University, public domain via Wikipedia).

Variola, more commonly known as “smallpox,” was an acute infectious disease that, even in the mildest of cases in 1861, was highly contagious. Notable for the high fever it caused, it also produced individual, boil-like eruptions across the human body. Known as “pocks,” these eruptions would quickly become fluid-filled pustules — even with the weakest strains of the disease — that would, if sufferers survived, eventually burst, leaving them badly scarred.

If, however, the soldier contracted the most virulent form of the disease — Variola confluens — as happened with at least one member of the 47th Pennsylvania — the suffering and likelihood of death was much, much greater. Far more severe than the strain that would have typically sickened the average child or adult during the mid-1800s, Variola confluens produced patches of pustules, rather than individual pocks. Forming on the face in such large swaths, the skin of the soldier who had been unfortunate to contract this strain of the disease would have appeared to have been burned or blistered. In addition to the horrific facial disfigurement, that soldier would also likely have experienced hair loss, severe pain and damage to his mucous membranes, mouth, throat, and eyes as the fever ravaged his body and continued to climb. If the disease devolved into the hemorrhagic phase prior to his death, the pocks on his face and mucous membranes would then also have begun to bleed.

Most likely exposed to the disease sometime while they were encamped in Virginia with their regiment, the first of the 47th Pennsylvanians to contract Variola would not initially have noticed any symptoms during this disease’s ten to fourteen-day incubation period. The first symptoms they would have experienced would have been due to rigor (sudden chills as the onset of fever began, alternating with shivering and sweating). As this primary fever increased, their temperatures would have risen to 103° or 104° Fahrenheit or higher over a two-day period, quickening the pulse and causing intense thirst, headache, constipation, vomiting, and back pain. As their conditions worsened, they might also have experienced convulsions and/or a redness on their abdomens or inner thighs — markings which might have appeared to be a rash of some sort or the beginnings of scarlet fever, but which were, in fact, a series of small, flat, circular spots on the body caused by bleeding under the skin and known as “petechiae.”

It would only have been on roughly the third day, post-incubation period, that these same men would have noticed that their faces were erupting with boils, but even then, they might have missed this sign because such pocks typically appeared as a single patch of redness on the sufferer’s forehead, near the roots of the hair. Within hours of this first eruption, however, the soldiers would most certainly have realized that something was wrong as they began scratching to relieve the itching on patches that had spread across their faces and bodies — particularly when the pocks began to fill with fluid and swelled to pea-sized bumps.

Likely sent to the regiment’s hospital sometime around this time, these 47th Pennsylvanians would have been transferred to the eruptive fever hospital on the Kalorama Heights in Georgetown before the week was out because, by day eight or nine, their skin would have become inflamed and swollen as the fluid in the pocks changed from clear to yellow, began to smell, and spread to their mouths, throats, noses, and eyes, putting their breathing and vision at risk. Increasingly hoarse, despite the increase in saliva they were experiencing, their bodies would then also have been overtaken by secondary fever, followed possibly by delirium and then coma.

If they somehow managed to survive until the disease’s latter phase, the pustules would have eventually dried up (typically on the twelfth day, post-incubation); if they didn’t, death most likely would have ensued due to myocardial insufficiency caused by the weakening of their heart muscles.

Typhoid Fever

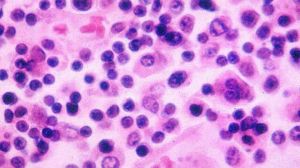

An image of Salmonella typhi, the bacteria which cause typhoid fever (U.S. Armed Forces. Institute of Pathology, public domain).

Often confused with the insect-borne typhus fever, typhoid fever is caused by bacteria. Poorly understood well into and beyond the mid-nineteenth century, despite having sickened countless numbers of individuals since the time of Hippocrates, according to American University historian Thomas V. DiBacco, typhoid fever’s method of transmission remained unidentified until 1856. That year, it finally dawned on scientists that fecal matter contaminated with Salmonella typhosa, one of the strains of bacteria now known to cause food poisoning, was at the root of the “persistently high fever, rash, generalized pains, headache and severe abdominal discomfort,” and intestinal bleeding of the patients physicians were failing to save.

Spread by the unsanitary conditions so common to the close living quarters shared by America’s Civil War-era soldiers, as well as by their respective regimental company cooks who were often forced to prepare meals with unclean hands when their regiments stopped briefly during long marches, the typhoid fever-causing Salmonella typhosa bacterium would typically enter a soldier’s body “through food, milk or water contaminated by a carrier,” but might also have been contracted just as easily via a bite from one of the many flies swarming around a regiment’s latrine facilities or horses.

And, because the “worst manifestations” of the disease did not appear until two or three weeks into an individual’s illness, according to DiBacco, typhoid fever was able to spread like wildfire not just during its incubation period, but even when soldiers were aware that others within their respective companies were ill because “typhoid victims were disposed to think the malady less serious as time went by.”

It is this latter fact alone that, perhaps, explains why outbreaks of typhoid fever continued to plague the 47th Pennsylvania throughout the duration of the war when Variola did not.

The First ”Men” to Die

Court House, Sunbury, Pennsylvania, 1851 (James Fuller Queen, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The first “man” to die from the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was John Boulton Young, a thirteen-year-old drummer boy who was known affectionately as “Boulty” (alternatively, “Boltie”). A member of the regiment’s C Company, he served under Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin, but was known to, and beloved by, the majority of the roughly one thousand men who served with the 47th.

Born on 25 September 1848 in Sunbury, Pennsylvania as the second oldest son of Pennsylvania natives, Michael A. and Elizabeth (Boulton) Young, Boulty was still in school at the time of his enlistment for Civil War military service in his hometown on 19 August 1861. He clearly lied about his age on military paperwork that day, indicating that he was fourteen, rather than twelve — a fiction which was maintained by Gobin and his fellow C Company officers throughout the boy’s tenure of service.

* Note: According to historians at the American Battlefield Trust, “For most of the war, the minimum enlistment age in the North was legally held at 18 for soldiers and 16 for musicians, although younger men could enlist at the permission of their parents until 1862. In the South, the age limit for soldiers stayed at 18 until 1864 when it was legally dropped to 17.”

Just four feet tall at the time of his official muster in at the rank of musician (drummer boy) at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg on 2 September, Boulty was so small that his superiors needed to customize both his uniform and his drum to make it easier for him to function as a member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

The Kalorama Eruptive Fever Hospital (also known as the Anthony Holmead House in Georgetown, D.C. after it was destroyed in a Christmas Eve fire in 1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

After completing basic training and traveling by train with his regiment to the Washington, D.C. area in mid-September, Boulty subsequently endured several long marches, including at least one undertaken in a driving rain. By late September or early October of 1861, Boulty had contracted such a challenging case of Variola (smallpox) that regimental surgeons ordered his superiors to ship him from Virginia, where the 47th Pennsylvania was encamped as part of the Army of the Potomac, to the eruptive fever hospital on the Kalorama Heights in Georgetown, District of Columbia.

Diagnosed by the physicians there with Variola confluens, the most virulent form of the disease, he died at that hospital on 17 October 1861. His body was then quickly prepared and transported for burial. Initially interred in Washington, D.C. at the Soldiers’ Asylum Cemetery (now known the United States Soldiers’ and Airmen’s Home Cemetery), his remains were disinterred in early 1862, and returned to Pennsylvania for reburial at Penn’s Cemetery in his hometown of Sunbury.

To learn more about Boulty’s life before and during the Civil War, as well as what happened to the surviving members of his family, read his biographical sketch, The First “Man” to Die: Drummer Boy John Boulton Young.

Alfred Eisenbraun

The second “man” from the 47th Pennsylvania to die was also a drummer boy — fifteen-year-old Alfred Eisenbraun, who served with the regiment’s B Company. A native of Allentown, Pennsylvania who was born in June of 1846, he was a son of Johann Daniel Eisenbraun, a noted Frakturist and tombstone carver who had emigrated from Württemberg, Germany to the United States in 1820, and Lehigh County, Pennsylvania native Margaret (Troxell) Eisenbraun.

Unlike “Boulty,” however, Alfred Eisenbraun had already left his studies behind, and had joined his community’s local workforce in order to help support his family. Employed as a “tobacco stripper,” he separated tobacco leaves from their stems before stacking those leaves in piles for the creation of cigars or chewable tobacco. As he did this, he likely would have been “breathing foul air, in rooms bare and cold or suffocatingly hot”, possibly “in a damp basement, musty with mould [sic] or lurking miasma,” according to Clare de Graffenried, a 19th-century U.S. Bureau of Labor employee who researched and wrote extensively about child labor.

So, it comes as no surprise that a boy in Eisenbraun’s situation would have viewed service with the military as a vast improvement over his existing job — especially if the pay was higher — which it most certainly was. Just barely fifteen when he enrolled for Civil War service in his hometown on 20 August 1861, Eisenbraun officially mustered in at the rank of musician (drummer boy) with the 47th Pennsylvania’s Company B at Camp Curtin on 30 August. Military records at the time described him as being five feet, five inches tall with black hair, black eyes and a dark complexion. His commanding officer was Captain Emanuel P. Rhoads.

Like Boulty, Eisenbraun completed basic training, traveled by train with his regiment to the Washington, D.C. area in mid-September, and then endured several long marches, including the same one that was undertaken in a driving rain. And, like Boulty, Eisenbraun also fell ill in late September or early October.

The Union Hotel in Georgetown, District of Columbia became one of the U.S. Army’s general hospitals during the American Civil War (image circa 1861-1865, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

But unlike Boulty, Eisenbraun was felled by typhoid fever. According to regimental historian Lewis Schmidt, the teen “had been sick almost from the time the regiment left Camp Curtin” in mid-September. After initially receiving treatment from regimental physicians through at least mid-October, he was sent back to the Washington, D.C. area to receive more advanced care. Per Schmidt, two of Eisenbraun’s fellow B Company members “visited Alfred at the fort on the 21st … and found him getting better, pleased to see them, and happy to engage in some conversation.”

But on Thursday morning, 24 October, after Captain Rhoads headed over to the fort’s hospital nearby, he was informed that Eisenbraun “and all the other sick men had been moved to the General Hospital in Georgetown.” Assuming that Eisenbraun’s condition had improved, since he’d apparently been deemed well enough to travel, Rhoads returned to his camp site, confident that he’d see the boy again — but he was wrong.

Eisenbraun, it turned out, had been transported to the former Union Hotel in Georgetown, which had been converted into one of the U.S. Army’s general hospitals. He died there from typhoid fever on 26 October 1861. Like Boulty, he was laid to rest at the Soldiers’ Asylum Cemetery in Washington, D.C.; unlike Boulty, however, his remains were never brought home.

To learn more about Alfred’s life before and during the Civil War, read his biographical sketch, Alfred Eisenbraun, Drummer Boy – The Regiment’s Second “Man” to Die.

The Third to Die: Sergeant Franklin M. Holt

Franklin M. Holt had already distinguished himself before becoming the first “true man” from the 47th Pennsylvania’s rosters to die. The regiment’s third fatality, he was also one of a handful of non-Pennsylvanians serving with this all-volunteer Pennsylvania regiment.

Born in New Hampshire in 1838, Frank Holt was a son of Cambridge, Massachusetts native, Edwin Holt, and Mont Vernon, New Hampshire native, Susan (Marden) Holt. A farmer like his father, he left his home state sometime around the summer of 1860, and took a job as a “map agent” in Monmouth County, New Jersey. But by the spring of 1861, he had relocated again, and had adopted the Perry County, Pennsylvania community of New Bloomfield as his new hometown.

That same spring, when President Abraham Lincoln issued his call for seventy-five thousand volunteers to help defend the nation’s capital following the fall of Fort Sumter to troops of the Confederate States Army, Holt enrolled with Company D of the 2nd Pennsylvania Infantry, completing his Three Months’ Service from 20 April to 26 July 1861 under the leadership of Henry D. Woodruff.

Realizing that the fight to preserve America’s Union was far from over, Holt re-enlisted in the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry’s D Company, which was also commanded by Captain Woodruff. Following his re-enrollment on 20 August in Bloomfield, he then re-mustered at Camp Curtin on 31 August at the rank of sergeant and, like drummer boys John Boulton Young and Alfred Eisenbraun, completed basic training before traveling with the regiment to the Washington, D.C. area for service with the Army of the Potomac.

Enduring a climate of torrential rain and pervasive, persistent dampness during his early days of service, Holt ultimately also fell ill with Variola (smallpox) and, like drummer boy Young who had also contracted the disease, he was transported to the eruptive fever hospital on the Kalorama Heights in Georgetown, District of Columbia, where he was treated by at least one of the same physicians who treated Boulty. Despite having apparently been diagnosed with a less severe form of the disease (according to military records which noted that Holt was sickened by Variola rather than the Variola confluens that felled Boulty), Sergeant Holt died at Kalorama on 28 October 1861.

“Kind, gentlemanly courteous, and honest in all his transactions,” according to the New Bloomfield Democrat, Holt had also “won for himself the esteem of all who knew him” prior to his untimely death. Like the two young drummer boys before him, he too was buried quickly at the Soldiers’ Asylum Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Although his remains were also never returned home, Holt was ultimately honored by members of his family, who erected a cenotaph in his honor at the Meadow View Cemetery in Amherst, New Hampshire.

To learn more about Frank’s life before and during the Civil War, read his biographical sketch, Holt, Franklin M. (Sergeant).

To learn more about Civil War Medicine, in general, as well as the battle wounds and illnesses most commonly experienced by members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, please visit the Medical section of this website.

Sources:

- Affleck, M.D., J. O. “Smallpox,” in “1902 Encyclopedia.” Encyclopedia Britannica, 9th and 10th editions (online), 2005-2019.

- Alfred Eisenbraun (obituary). Allentown, Pennsylvania: Lehigh Register, 30 October 1861.

- Alfred Eisenbraun (obituary), in “Gestörben.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: Der Lecha Caunty Patriot, 6 November 1861.

- Allen Eisenbraun (death notice), in “Deaths of Soldiers.” Washington, D.C.: The Evening Star, 28 October 1861.

- Barker, M.D., Lewellys Franklin. Monographic Medicine, Vol. II: “The Clinical Diagnosis of Internal Diseases,” p. 431 (“Variola confluens”). New York, New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1916.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol.1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- Burial Ledgers (Eisenbraun, Alfred; Holt, Franklin M.; Young, J. Bolton), in Records of The National Cemetery Administration and U.S. Departments of Defense and Army (Quartermaster General), 1861. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Casualties and Costs of the Civil War.” New York, New York: The Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.

- Civil War General Index Cards (Eisenbraun, Alfred and Eisenbrown, Allen), in Records of the U.S. Department of the Army. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration and Fold3: 1861.

- Civil War Veterans’ Card File, 1861-1865 (Eisenbraun, Alfred; Holt, Franklin M.; Young, J. Bolton). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- “Death of a Young Soldier” (obituary of John Boulton Young). Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania: Star of the North, Wednesday, 30 October 1861 (reprinted from the Sunbury Gazette).

- “Deaths of Soldiers” (death notice for John Boulton Young). Washington, D.C.: The National Republican, 18 October 1861.

- de Graffenried, Clare. “Child Labor,” in Publications of the American Economic Association, Vol. 5, No. 2. New York, New York: March 1890 (accessed 22 March 2016).

- DiBacco, Thomas V. “When Typhoid Was Dreaded.” Washington, D.C.: The Washington Post, 25 January 1994.

- “The Drummer Boy’s Monument” (monument erected to John Boulton Young). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 6 February 1864.

- Fabian, Monroe H. John Daniel Eisenbrown, in “Pennsylvania Folklife Book 62,” in Pennsylvania Folklife Magazine, Vol. 24, No. 2. Lancaster, Pennsylvania: 1975.

- Faust, Drew G. “The Civil War soldier and the art of dying,” in The Journal of Southern History, Vol. 67, No. 1, pp. 3-38. Houston, Texas: Southern Historical Association (Rice University), 2001.

- Holt Eulogy. New Bloomfield, Pennsylvania: New Bloomfield Democrat, 1861. Inkrote, Cindy. “Civil War drummer boy was different kind of hero.” Sunbury, Pennsylvania: The Daily Item, 4 October 2009.

- Letters of John Peter Shindel Gobin, 1861-1900. Various Collections (descendants of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, et. al.).

- “Registers of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-1865: 47th Regiment” (Companies B, C, and D) in Records of the Department of Military and Veterans’ Affairs (Record Group 19, Series 19.11). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State Archives.

- Sartin, M.D., Jeffrey S. “Infectious diseases during the Civil War: The triumph of the ‘Third Army,’” in Clinical Infectious Diseases, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 580-584. Cary, North Carolina: Oxford University Press, April 1993.

- Schmidt, Lewis. A Civil War History of the 47th Regiment of Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers. Allentown, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1986.

- U.S. Census. Washington, D.C. and Pennsylvania (Allentown and Sunbury, Pennsylvania; Amherst, New Hampshire; Monmouth, New Jersey): 1840-1930.

- U.S. Registers of Deaths of Volunteers, 1861 (Eisenbraun/Eisenbraum, Alfred; Holt, Franklin/Frank M; Young, J. Bolton/Jno. B.). Washington, D.C.: United States Army and U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

You must be logged in to post a comment.