George Dillwyn John (third from left; formerly, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers), Grand Army of the Republic, Will Robinson Post, Illinois, circa 1926.

Following the end of their service to the nation during the American Civil War and the early days of the Reconstruction era, the surviving members of the 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry were given honorable discharge paperwork from the United States Army that freed them to resume their old lives by returning home to their communities in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. That paperwork also empowered a surprisingly large number of 47th Pennsylvanians to begin life anew by migrating to the heartland of the United States or one of the nation’s border areas in search of greater prosperity and peace.

Westward Migration

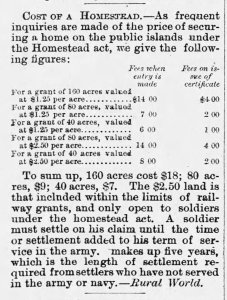

“Cost of a Homestead,” in The Indiana Progress, Indiana, Pennsylvania, 24 October 1872 (public domain).

One of the primary forces drawing 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers to the West was the availability of land that could be easily obtained at minimal to no immediate cost — with any payments that they might eventually be required to make deferred for periods of time that were, theoretically, long enough for them to earn the money needed to pay their bills. Made possible by the passage of the Homestead Act by the United States Congress in 1862, “any adult citizen, or intended citizen, who had never borne arms against the U.S. government” was allowed to “claim 160 acres of surveyed government land,” according to historians at the U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

Claimants were required to live on and ‘improve’ their plot by cultivating the land. After five years on the land, the original filer was entitled to the property, free and clear, except for a small registration fee. Title could also be acquired after only a six-month residency and trivial improvements, provided the claimant paid the government $1.25 per acre. After the Civil War, Union soldiers could deduct the time they had served from the residency requirements.

“By 1890,” according to the United States Senate Historical Office, “the federal government had granted 373,000 hometeads on some 48 million acres of undeveloped land.”

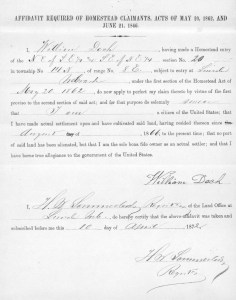

Homestead claim affidavit filed by William Dech, a brother of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Alfred Dech, for land in Nebraska (U.S. Homestead Records, 10 April 1872, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and their relatives who obtained land in this manner would likely have paid individual filing fees of roughly ten to fourteen dollars “to claim the land temporarily,” plus an additional two to four dollars in commission fees to their respective land agents, according to historians at the U.S. National Park Service and newspapers of the 1870s. Those same 47th Pennsylvanians or their relatives then became farmers on the land they had claimed. In hindsight, many of those plots were located on ground that had been taken away from Native Americans. Although the Dawes Act of 1887 “designated 160 acres of farmland or 320 acres of grazing land to the head of each Native American family” and “the tribes controlled the land now being allotted to them … much of the land subject to the Dawes Act was unsuitable for farming,” according to National Park Service historians. As a result, “large tracts were leased to non-Native American farmers and ranchers.” In addition, [a]fter the Native American families claimed their allotments, the remaining tribal lands were declared ‘surplus'” and “given to non-Native Americans.”

Native American lands decreased significantly under the Dawes Act. Reservation lands went from 138 million acres in 1887 to 48 million aces in 1934 … a loss of 65 percent, before the Dawes Act was repealed.

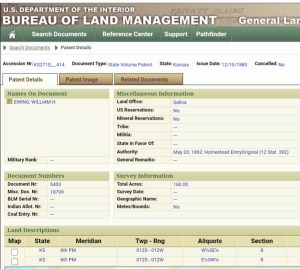

William H. Ewing’s Homestead Patent for one hundred and sixty acres of land in Kansas, 10 December 1880 (U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, patent database, public domain, retrieved online 27 January 2025; click to enlarge).

The Dawes Act, however, was not the only contributing factor in that sweeping redistribution of land. According to Homesteading the Plains: Toward a New History, while “homesteading was an important driver of dispossession” in the Dakotas and Oklahoma, “the primary drivers of dispossession” in Colorado and Montana, “were mining interests, railroads, land speculators, and big cattle ranchers with homesteading playing a very minor role.” And in Nebraska, “forces other than homesteading produced virtually all dispossession.”

Veterans of the 47th Pennsylvania who migrated west and became farmers or millers after the American Civil War included: William Ewing (Kansas), Reuben Shatto Gardner (Minnesota), Richard A. Graeffe (Michigan), George Dillwyn John (Illinois), Samuel Noss (Indiana), David C. Rose (Indiana), Lewis W. Saylor (Iowa), and James M. Sieger (Missouri).

Additional Forces Which Inspired 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Migration

A second force which motivated a number of 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers to relocate from the Great Keystone State to other areas of the United States was the expansion of America’s network of railroad lines throughout and beyond the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Those expansion efforts ultimately led to the completion of The Transcontinental Railroad.

“It had taken the bloodshed and sacrifice of the Civil War to reunite the nation, North and South. But when the war was over, Americans set out with equal determination to unite the nation, East and West,” according to American History documentarian Stephen Ives.

To do it they would build a railroad. Its completion would be one of the greatest technological achievements of the age, signaling at last, as nothing ever has, that the United States was not only a continental nation, but on its way to becoming a world power.

And when the railroad was finally built, the pace of change would shift from the steady gait of a team of oxen, to the powerful surge of a steam locomotive. The West would be transformed.

Overnight, the railroad would turn barren spots of earth into raucous boomtowns…. The railroad would allow Civil War veterans, poor farmers from the East, and landless peasants from Europe to have a farm they could call their own. There they planted foreign strains of wheat in rich, matted prairie soil that had never known anything but grass…. Railroads would carry hundreds of thousands of western longhorns to eastern markets….

“Railroads had already transformed life in the East, but at the end of the Civil War, they still stopped at the end of the Missouri River,” according to Ives.

For a quarter of a century, men had dreamed of building a line coast to coast. Now, they would attempt it. One thousand seven hundred and seventy-five miles of track from Omaha to Sacramento. It would have to be cut through mountains higher than any railroad builder had ever faced, span deserts where there was no water anywhere, and cross treeless prairies where anxious and defiant Indians would resist their passage….

The West couldn’t be settled without railroads, and a railroad across the West couldn’t be built without the government. The distances were too great, the costs too staggering, the risks too high for any group of businessmen….

In 1862, Congress gave charters to two companies to build it. The Central Pacific was to push eastward from Sacramento, over the Sierra Nevada Mountains. The Union Pacific was to start from the Missouri, cross the Great Plains, and cut through the Rockies. Most companies were to receive vast loans from the Treasury as they went along — sixteen thousand dollars per mile of level track, thirty-two thousand in the plateaus, and forty-eight thousand in the mountains. Lobbyists got the rates doubled within a year….

Congress also promised each company sixty-four hundred acres of federal land for every mile of track it laid….

In Nebraska, some ten thousand men were at work on the Union Pacific, heading west. Most were immigrants from Ireland, but there were also Mexicans and Germans, Englishmen, ex-soldiers, and former slaves — an army of workmen, moving across the Plains with military precision….

Each rail weighed seven hundred pounds. It took five men to lift it into place. Two or three miles a day — every day. Six days a week — week in and week out.

Among the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers or their families who found work in the railroad industry were: Atkinson Brady (Northern Central Railway, Pennsylvania), Edward L. Clark (unidentified Pennsylvania railroad company), John D. Colvin (engineer, Pacific Railroad; assigned to extend the line from Atchison, Kansas to Fort Kearney in Nebraska), Reily M. Fornwald (Reading Railway Company, Pennsylvania), John A. Gardner (fireman, Pennsylvania Railroad), Reuben Shatto Gardner (street car conductor, Seattle, Washington), Phaon Guth (section boss, Catasauqua and Fogelsville Railroad, Pennsylvania), Charles and Martin Hackman (Philadelphia and Reading Railroad, Pennsylvania), Daniel Oyster (railroad postal agent, unidentified company), Samuel H. Pyers (soldier stationed in Omaha, Nebraska with the U.S. Army’s 30th Infantry; assigned to guard a Union Pacific Railroad line that was under construction near Hot Springs; subsequently stationed in the Black Hills of South Dakota), Peter S. Reed (executive, Colorado Central Railroad, and a brother-in-law of Washington Alexander Power), and Charles H. Small (freight car manufacturing clerk, Harrisburg Car Manufacturing Company, Pennsylvania).

A third force driving the migration of 47th Pennsylvania veterans was the rapid growth of employment opportunities in the mining industry as coal and oil became standardized heating and lighting fuels for homes and businesses. “Rush fevers” also swept the nation as news reports of mineral and metal booms inspired thousands to stake claims on lands where they could prospect for gold and copper.

Veterans of the 47th Pennsylvania employed in the mining industry included: John D. Colvin (superintendent, Delaware & Hudson Coal Company and, later, the Lehigh Valley Coal Company, Pennsylvania), Reuben Shatto Gardner (gold prospector, Western United States and British Columbia, Canada), Martin Luther Guth (prospector and miner, New Mexico, Nevada and California), and Washington Alexander Power (copper smelter, Golden and Trinidad, Colorado).

In addition to securing jobs as farmers, railroad workers or miners, veterans of the 47th Pennsylvania and their descendants also pursued employment as bakers, bookkeepers, bridge builders and other carpenters (Thomas Burke and George Kosier, Iowa), cattlemen (Charles Marshall, Kansas and New Mexico), cigarmakers, civil engineers (H. B. Robinson and his son, Horace Brady Robinson, Jr.), clockmakers, firemen, hoteliers, ironworkers (Spencer Tettemer, Arkansas, after relocating from Missouri), janitors (William Schuyler Reiser, South Dakota), jewelers (Charles Bachman, Iowa), lumbermen, machinists, mechanics, newspaper publishers, an optometrist, painters, policemen, postmasters, quarrymen, restauranteurs, saloon owners, stone carvers, tailors, tanners, teamsters, tinsmiths (Franklin Sieger, Ohio), and watchmakers/repairmen (Elias Franklin Benner, Indiana, after working as a piano tuner in Ohio). A fair number owned their own small businesses.

Captain Theodore Mink, Company I, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers (circa 1870s-1880s, courtesy of Julian Burley; used with permission).

Opting for a complete change, Theodore Mink, a whaler and coachmaker prior to the war, opted to “run off and join the circus” after receiving his honorable discharge paperwork. His post-war travels ultimately took him from Portland, Maine to San Bernardino, California and back.

At least three descendants of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantrymen made it as far west as Hawaii. Louise (Troell) Spreckels, a niece of John H. Troell, migrated to Kauai, where her husband Richard was employed as “head chemist at the Kilauea plantation” during the early 1920s. Her daughter and namesake, Louise Spreckels, subsequently became a teacher at the Koolau School in Kauai (in January 1924). And Corinne (Snyder) Johanos, a great-granddaughter of Timothy M. Snyder, became a resident of Honolulu, Hawaii circa the 1980s. A classically-trained pianist, Corinne Johanos served on the boards of directors of the Hawaii Opera Theater and the Honolulu Symphony Associates before relocating to Naples, Florida in 1997.

Health as Another Motivating Factor to Migrate

Veterans at dinner, U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, Leavenworth, Kansas, 1895 (Matthew H. Jamison, Fort Leavenworth and the Soldiers’ Home, 1895, public domain).

A fourth migration driver for former 47th Pennsylvanians was their persistent suffering from chronic conditions that had been caused by wounds received in battle or diseases that had sickened them during their Civil War service. For many, those mental and physical ailments were compounded by feelings of isolation, particularly for those who had never married or were estranged from their families. As a result of that particular factor, many 47th Pennsylvanians relocated to the northeast, southeast or westward, driven by their need for higher quality, more affordable healthcare and a renewed sense of camaraderie and community that could only be accessed in a city or town where one of the branches of the U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers was located.

Among the 47th Pennsylvanians who were admitted to soldiers’ homes were: Benjamin Amey (Kansas and Illinois), David K. Bills and William R. Fertig (Virginia and then Ohio), William Brecht (Ohio), Washington Scott Johnston and Alfred Lynn (Tennessee), Charles Marshall (Kansas), Lawrence McBride and Edward Newman (Ohio), Jacob Petre (Ohio and Virginia), and John G. Tag (Kansas).

Martin Luther Guth, who resided at the Veterans’ Home of California in Yountville, Napa County circa 1900, was subsequently transferred to the National Soldiers’ Home in Tennessee before returning to California, where he lived alone in Oakland and volunteered with his local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.). James Downs, a former prisoner of war, spent his final years at the Pennsylvania Memorial Home in Brookville, Jefferson County, Pennsylvania.

Others, like Daniel Battaglia and Ephraim Clouser, were far less fortunate, requiring lengthy or permanent hospitalizations due to serious mental illnesses.

A fifth motivator appears to have been an odd desire for anonymity, as was the case with Private Joseph Slayer, who was known by various names after he settled in what is now the city of Bismarck, North Dakota (a place where he could forge new identities as “Dead Eye Dick” and “E. J. McMeeser” in the late 1880s).

Resettling in the South

At least four of the nine formerly enslaved Black men who enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania during the American Civil War are confirmed to have resettled in America’s Deep South, following their respective honorable discharges from the regiment in Charleston, South Carolina during the fall of 1865.

According to records of the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, U.S. Census records of the late nineteenth century and U.S. Civil War Pension records, both Bristor Gethers and Thomas Haywood returned to South Carolina — the state where they had been enslaved prior to the American Civil War.

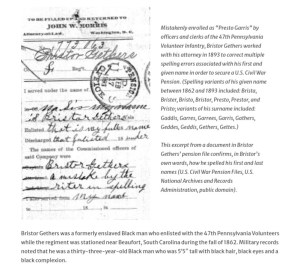

Attestation by 47th Pennsylvanian Bristor Gethers and his attorney, 24 January 1893, confirming the correct spelling of his name (U.S. Civil War Pension Files, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain; click to enlarge).

Gethers, who was mistakenly listed on the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental rosters as “Presto Gettes,” was signed to a contract on 12 February 1868, with fourteen other Freedmen, by the Mt. Pleasant, South Carolina office of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which obligated the men to provide farm labor for the White House Plantation in Berkeley County, South Carolina. By 1870, he was residing with his wife and son in Beaufort Township, Beaufort County, South Carolina, where he was involved in farming land valued at fifteen hundred dollars (roughly the equivalent of thirty-four thousand U.S. dollars in 2022). Residents of Port Royal, Beaufort County by 1889, he and his wife made their home on Horse Island during their final years.

Haywood was also signed to labor contracts by the Freedmen’s Bureau between 1866 and 1868. In exchange for agreeing to plant and cultivate cotton for several men who had been plantation owners in the Beaufort, Berkeley and Mt. Pleasant areas of South Carolina, on three to five-acre parcels of land that had been leased to him by those men, he was allowed to keep portions of the sale of that cotton (the largest portions of which went to the former plantation owners who had likely been active participants in, and financial beneficiaries of, the Lowcountry’s system of chattel slavery prior to and during the Civil War). Treated for remittent fever by U.S. Freedmen’s Bureau physicians during this same period, he subsequently settled in Sheldon Township, Beaufort County and lived to witness the dawn of a new century.

Letter of inquiry from J. H. Chapman on behalf of Hamilton Blanchard to E. B. French, second auditor, U.S. Treasury Department, 10 November 1868 (Freedmen’s Bureau records, U.S. National Archives; click to enlarge).

Also according to Freedmen’s Bureau records, U.S. Census records of the late nineteenth century and U.S. Civil War Pension records, both Aaron French (known during enslavement as Aaron Bullard) and Hamilton Blanchard initially made their way north during or around the same time that other members of their regiment were returning home to Pennsylvania. Freed from slavery in Louisiana, they had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania with three other formerly enslaved men in Natchitoches, and had traveled with the regiment until they were honorably discharged in Charleston, South Carolina during the winter of 1865.

Freedmen’s Bureau records documented that both men were residents of Washington, D.C. by late January or early February 1866 and that, while there, both had met with representatives of the Freedmen’s Bureau. During that meeting(s), both agreed to commit themselves to a Freedmen’s Bureau labor contract, which obligated them to join a large group of formerly enslaved men, women and children in providing farm labor to a man named John P. Avrill (alternate spellings: “Averile,” “Averill,” “Arvile,” “Arville,” or “Avrille”) at his property in Canton, Madison County, Mississippi between 16 February and 16 December 1866.

Two years later, on 10 November 1868, J. H. Chapman, a sub-assistant commissioner employed by the Freedmen’s Bureau in Mississippi, penned a letter of inquiry to E. B. French, second auditor of the U.S. Department of Treasury in Washington, D.C., in which he asked to “be informed what decision has been made of the claim of Hamilton Blanchard, late of Co. “D” 47 Penn Vol. Inft., his discharge was received by J. R. Schuchard[?],” of the “Freedmen’s Aid Commission, March 15, 1866.” Stating that he was making that request on behalf of Blanchard “for the purpose of prosecuting his claim against the Gov.”, he added that he was also requesting “information concerning the claim of Aaron Bullard (Col.) who belonged to same company & regiment.”

That letter appears to indicate that Blanchard and French had lost touch with each other less than three months after agreeing to the Freedmen’s Bureau contract in Washington, D.C. Although little is known about Blanchard’s whereabouts after this time, researchers for 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers: One Civil War Regiment’s Story have been able to determine that Aaron French made a new life for himself and his wife and children in Issaquena County, Mississippi. His descendants now reside in multiple communities across America.

First Lieutenant and Regimental Adjutant Washington H. R. Hangen, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, circa 1864 (public domain).

Other members of the regiment also chose to remain in, or return to, southern states where the regiment had been stationed during the war. One, Washington H. R. Hangen, was employed by the Freedmens’ Bureau to manage services for Black men, women and children in Louisiana’s St. Tammany and Washington parishes. After completing his assignment, Hangen found work as a surveyor in Louisiana and lived out the remainder of his life there.

Samuel Barber Woodring relocated to Sanibel County, Florida during the 1880s and lived on Sanibel Island until shortly before his death in Fort Myers, Florida.

Resettling in the Northeast

Closer to home, New Jersey benefitted from one of the largest, most sustained 47th Pennsylvania migrations with multiple members of the regiment choosing to settle in Phillipsburg, Warren County, including: John Diaz, Uriah Meyers, Francis J. Mildenberger, Eli Moser, George Reuben Nicholas, Peter Osterstock, John J. Paxton, and John J. Schofield. Others resided elsewhere in the state, including: Aaron Rader, George Rockafellow, Hugh Bellas Rodrigue, the Rev. William Rodrock, Thomas Rogers, Matthias Schmidt, Barnet Searfoss, Jefferson Stem, Andrew Thoman, and Oliver Van Billiard.

But Daniel K. Reeder, who lost an arm during the war, opted to settle in Dover, Delaware. A successful inventor, he also traveled regularly to and from Washington, D.C.

James Turner Rider, Sr. and David Livingston Sloan were two of the other 47th Pennsylvanians who moved closer to the nation’s capital. Rider resided in Baltimore, Maryland after the turn of the century, while Sloan lived in Elkton, Maryland.

Paul Strauss, on the other hand, apparently felt the need to remain on the East Coast, but be as far away from Washington, D.C. as possible. So, he relocated to Kennebec County, Maine during the 1870s, and found work as a carpenter. On 9 May 1882, he wed Lizzie Norton in the town of Waterville and became a farmer and father. By 1900, he and his family were living in Albion, Kennebec County. Following his death from heart disease at the U.S. National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers in Togus, Maine in 1926, he was laid to rest beside his wife at the Albion Cemetery No. 4 in Albion.

Jenkin J. Richards was another of the 47th Pennsylvanians who moved to New England. An 1844 emigrant from Wales in the United Kingdom who subsequently settled in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania prior to the Civil War, he became an ironworker, post-war, after migrating to Massachusetts, and witnessed the dawn of a new century before passing away in Worcester, Worcester County in 1911.

Mathias Snyder settled in Albany, New York during the 1870s, where he was gainfully employed as a piano maker, while his son worked as a piano tuner.

Residency in Non-U.S. Locations

Choosing to make their own marks even farther away, several veterans of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry or their siblings and descendants made lives for themselves outside of the United States, residing temporarily or permanently where they were employed in business, military or public service jobs. Among the most adventurous of these souls were: Walter Henry Brunell, who settled in Calgary, Alberta, Canada, where he was employed by the Husky Oil Co.; Margaret R. (Grant) Schutte, who settled in South Africa, where she had been appointed to the faculty of Transvaal University College (later the University of Pretoria); and Conrad Troell, who worked as a miner in Central America during the mid-1860s.

Making The Communities Where They Lived Better

Brevet Brigadier-General John Peter Shindel shown here in 1897 as Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic.

Multiple veterans of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry and their descendants positively impacted the towns and cities they called home by pursuing public service careers. Among those leading the charge for improvements to government operations, public education and public safety in Pennsylvania were: John Peter Shindel Gobin, who was elected to the Pennsylvania State Senate before becoming a lieutenant governor of Pennsylvania, William M. Hendricks, who was elected as a city inspector and then as a justice of the peace in the Borough of Sunbury, and Conrad Volkenand, who was elected as the Luzerne County Recorder in 1880.

Aaron French, one of the nine Black soldiers mentioned above in “Resettling in the South,” was appointed as a delegate from Issaquena County, Mississippi to the Republican Congressional Convention for the Third District, which was held in Greenville, Mississippi on 7 August 1886.

Born into slavery in Mississippi, Aaron French had enlisted with the 47th Pennsylvania as “Aaron Bullard” after having been freed from continued enslavement near Natchitoches, Louisiana in April 1864, and had lived briefly in Washington, D.C. before returning to the Deep South to work, marry and begin a family. After resettling in Mississippi with his wife, he had become a farmer and land owner, had also become increasingly active, politically, and had inspired his descendants to become socially and politically active in their own communities.

His daughter, Jessie (French) Cobb (1876-1913), grew up to become a teacher in the public schools of Mayersville, Mississippi. One of his great-grandsons, Richard Henry Jones (1935-2001), became a medical research photographer with St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital in Memphis, Tennessee, and was also greatly respected for his efforts to create a photographic records of the history of the Civil Rights movement in Memphis.

John Albert (“Jack”) Snyder, a great-grandson of Corporal Timothy Matthias Snyder, rose through the ranks to become a lieutenant-colonel in the United States Air Force. Stationed in Förch, Baden-Württemberg, Germany, at the age of twenty-two, he was relocated by the Air Force for various duty assignments throughoit his career. Settling in Greenville, Mississippi during the early to mid-1950s and Burlington, Vermont during the late 1950s, he was then stationed at the Yokota Air Base in Tokyo, Japan during the early 1960s. Additional duty assignments that decade took him to in Korea and Vietnam. After serving again in Germany during the early 1970s, he subsequently returned to the United States, where he made his home in Killeen and Harker Heights, Texas during the 1980s and 1990s.

Sources:

- “93 Years Old; Falls Breaking His Left Thigh: Samuel Transue: Fremont’s Oldest Living Resident, Injured.” Fremont, Ohio: The Fremont Messenger, 13 November 1926.

- “A Terrible Position” (injury of John A. Gardner during railcar uncoupling accident). Bloomfield, Pennsylvania: The Perry County Democrat, 5 November 1873.

- Admissions Ledgers, U.S. National Soldiers’ Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers (California, Indiana, Kansas, Maine, Ohio, Tennessee, Wisconsin). Washington, D.C., 1912-1935.

- “Aged Vet Dies in Fremont Home” (obituary of Samuel Transue). Sandusky, Ohio: Sandusky Register, 7 December 1926.

- “Another Civil War Veteran Is Mustered Out” (obituary of Samuel Transue). Fremont, Ohio: Fremont Messenger, 6 December 1926.

- Atkinson Brady (mention of his work-related, Northern Central Railway accident). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Telegraph, 6 April 1871.

- Bachman, Charles, in The History of Wapello County, Iowa, Containing a history of the County, its Cities, Towns, &c., A Biographical Directory of Citizens, War Record of its Volunteers in the late Rebellion, General and Local Statistics, Portraits of Early Settlers and Prominent Men, History of the Northwest, History of Iowa, Map of Wapello County, Constitution of the United States, Miscellaneous Matters, &c. Chicago, Illinois: Western Historical Company, 1878.

- “Body of Pioneer Sent to Seattle” (death of Edward Gardner, a son of 47th Pennsylvanian Reuben Shatto Gardner). Spokane, Washington: Spokane Chronicle, 22 January 1937.

- “Brothers Who Parted on Battlefields Forty Years Ago to March Side by Side in Big Parade.” San Francisco, California: The San Francisco Call, 17 August 1903.

- Chalkley John, in Portrait and Biographical Album of Whiteside County, Illinois, Containing Full-Page Portraits and Biographical Sketches of Prominent and Representative Citizens of the County, Together with the Portraits and Biographies of All the Governors of Illinois, and the Presidents of the United States. Chicago, Illinois: Chapman Brothers, 1863.

- Charles Bachman, in “Fire Does Damage: Loss Caused by Conflagration Early This Morning Estimated at $6,000.” Ottumwa, Iowa: The Ottumwa Courier, 1 March 1906.

- “Chas. Bachmann Ottumwan Is Farm Winner: Without Expense of Trip to the West, Local Merchant Draws Homestead in Couer [sic] D’Alene Reservation.” Ottumwa, Iowa: Ottumwa Tri-Weekly Courier, 12 August 1909.

- Clouser, Ephraim, Lizzie and Jacob, in U.S. Census (Supplemental Schedules, Nos. 1 to 7, for the Defective, Dependent, and Delinquent Classes: Insane Inhabitants in the Township of Centre and Borough of New Bloomfield, Perry County, Pennsylvania, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Conley, Chris. “Mr. Jones ‘had a real eye’ for capturing history on film” (news article about Richard Henry Jones, one of the descendants of 47th Pennsylvanian Aaron French). Memphis, Tennessee: The Commercial Appeal, 14 May 2001.

- “Corinne May Johanos,” in “Death Notices.” Naples, Florida: Naples Daily News, 21 December 2001.

- Cotroneo, Joel R. and Jack Dozier. “A Time of Disintegration: The Coeur d’Alene and the Dawes Act,” in Western Historical Quarterly, vol. 5, no. 4, October 1974. New York, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Davis, William W. History of Whiteside County, Illinois from Its Earliest Settlement to 1908: Illustrated, with Biographical Sketches of Some Prominent Citizens of the County, vols. 1 and 2. Chicago, Illinois: Pioneer Publishing Co., 1908.

- “Death of Capt. Theodore Mink.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Democrat, 15 January 1890.

- “Death of Jenkin Richards,” in “Catasauqua.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 18 March 1911.

- “Deaths” (notice of Daniel Battaglia’s death at the “Govt. Hosp. Insane.”). Washington, D.C.: Washington Post, 20 March 1909.

- Edwards, Richard, Jacob K. Friefeld and Rebecca S. Wingo. Homesteading the Plains: Toward a New History. Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 2017.

- Ewing, Charles (a Kansas-born son of 47th Pennsylvanian William Ewing), in Death Certificates (file no.: 29372, registered no.: 26, date of death: 10 March 1959). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- Ewing, William H., in State Volume Patents (Kansas, issued 10 December 1880), in General Land Office Records (accession nr.: KS2710_414). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management, retrieved online 26 January 2025.

- Ewing, William, Elmira, Jesse, Frances, Jane, Loretta, Harry, and Charlie, in U.S. Census (Fairview, Russell County, Kansas, 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Famous Ball Player’s Grand-Father Hale and Hearty at 90.” Fremont, Ohio: The Fremont Messenger, 8 September 1923.

- “Found Cold in Death” (death notice of Joseph Slayer, aka E. J. McNeeser). Bismarck, North Dakota: Bismarck Tribune, 14 January 1905.

- “Forepaugh’s Advance Brigade,” in “Hotel Arrivals: St. James Hotel.” Wheeling, West Virginia: Wheeling Daily Intelligencer, 14 July 1882.

- French, Aaron, in “Proceedings of the Third District Republican Convention.” Vicksburg, Mississippi: Vicksburg Evening Post, 9 August 1886.

- “Funeral Sunday” (funeral notice of Joseph Slayer, aka E. J. McNeeser). Bismarck, North Dakota: Bismarck Tribune, 17 January 1905.

- “Gardner,” in “Deaths and Funerals” and “Reuben S. Gardner Dies at Home: Old Resident of City, Grand Army Veteran and Four Years Employed in Local Postoffice [sic]” (obituary). Seattle Washington: The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, Saturday, 26 September 1903, pp. 12 and 16.

- Gardner, Reuben S., Mary A., Curtis, and Harvey, in Minnesota State Census (1875: Stillwater, Washington County, Minnesota). St. Paul, Minnesota: Minnesota Historical Society.

- Gardner, Reuben S., in U.S. Census (1880: Minneapolis, Hennepin County, Minnesota). Minnesota and Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Gardner, Reuben S., in U.S. Census (1900: Seattle, King County, Washington). Washington State and Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Gardner, Ruben [sic], Mary A., and Custis E. in U.S. Census (1870: Elk River Station, Sherburne County, Minnesota). Minnesota and Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Going to the Klondike: Seattle Is Crowded with the Alaskan Gold Hunters.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Telegraph, 16 December 1897.

- “History of the National Home for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers. Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online 23 January 2025.

- “Home on a Visit” (mention of 47th Pennsylvanian Theodore Mink). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Democrat, 24 October 1883.

- “Homestead Act” (1862), in “Milestone Documents.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, retrieved online 23 January 2025.

- Horace Brady Robinson, (Sr. and Jr.), and Melville Wilson Robinson in Cornell Alumni Directory, vol. XIII, no. 12. Ithaca, New York, 15 May 1922.

- “Horace Brady Robinson” (obituary of Horace Brady Robinson, Jr.). Franklin, Texas: The News-Herald, 4 May 1933.

- “Injuries Fatal to Aged Veteran” (obituary of Samuel Transue). Fremont, Ohio: The Fremont Daily News, 6 December 1926.

- Ives, Stephen. “The Transcontinental Railroad,” in, “The West,” in “Ken Burns in the Classroom.” Boston, Massachusetts: PBS Learning Media, retrieved online 23 January 2025.

- Jenkin J. Richards, in Death Certificates (registered no.: 567, date of death: 15 March 1911). Worcester, Massachusetts: Office of the Town Clerk.

- “John A. Gardner, Civil War Man, Dies; Aged 80: Lost a Hand in Pennsylvania Railroad Service Many Years Ago: Invalid Since December.” Reading, Pennsylvania: Reading Times, Thursday, 21 February 1918, p. 4.

- John, Clark E. History and Family Record of the “John” Family, 1683 to 1964: The Descendants of John Phillips and Ellen, His Wife, from Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire, Wales. Salt Lake City, Utah: Genealogical Society of the Church of Latter Day Saints, 1967.

- John D. Colvin (obituary). Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania: Wilkes-Barre Times, 15 March 1901.

- Kingsbury, George Washington. History of Dakota Territory, vol. III. Chicago, Illinois: The S. J. Clarke Publishing Company, 1915.

- “Klondike Rush: A Former Harrisburger Writes of the Pell-Mell Hunt for Gold.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Telegraph, 2 October 1897.

- Kosier, George, in U.S. Civil War Pension General Index Cards (application no.: 1319353, certificate no.: 1097759, filed by the veteran from Iowa on 23 June 1904). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Landmark Legislation: The Homestead Act of 1862,” in “The Civil War: The Senate’s Story.” Washington, D.C.: Senate Historical Office, United States Senate, retrieved online 25 January 2025.

- Locke, Joseph L. and Wright, Ben. The American Yawp. Palo Alto, California: Stanford University, January 2019.

- McLaurin, John J. Sketches in Crude Oil: Some Accidents and Incidents of the Petroleum Development in All Parts of the Globe. Franklin, Pennsylvania: Self-published, 1902.

- “Mining in the West,” in “Meeting of Frontiers.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. Library of Congress, retrieved online 23 January 2025.

- “Mystery of Deceased: Man Found Dead in His Room Yesterday Always Known by the Name of E. J. McNeeser: His Real Name Was Joseph Slayer and the Reason for the Change Is Not Known: Evidence of Family in the East Has Been Found — Served Through Civil War.” Bismarck, North Dakota: Bismarck Tribune, 15 September 1905.

- “Native Americans and the Homestead Act, in ” National Historical Park Nebraska: History & Culture: The Homestead Act.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online 25 January 2025.

- “Newport: Special Correspondence” (notice documenting Ephraim Clouser’s confinement and later death at the asylum in Harrisburg). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Daily Independent, 18 March 1899.

- “Obituary” (George D. John). Sterling, Illinois: Sterling Daily Gazette, 8 March 1928.

- “Obituary: Mrs. Mary Alice John.” Sterling, Illinois: Sterling Daily Gazette, 17 March 1937.

- “Pensions to Indianaians.” South Bend, Indiana: The South Bend Daily Tribune, May 30, 1899.

- Pidanick, Michael. “Lindsey’s Thomas was a major leaguer.” Fremont, Ohio: The News-Messenger, 29 July 1999.

- “Post-Civil War Westward Migration,” in “Conquering the West.” Lumen Learning, retrieved online 23 January 2025.

- “Prominent Oil City Man, H. B. Robinson, Dies” (obituary of Horace Brady Robinson, Sr.). Franklin, Pennsylvania: The News-Herald, 11 June 1926.

- “‘Red’ Thomas Signs with Chicago Cubs.” Fremont, Ohio: Fremont Daily Messenger, 16 August 1921.

- Richard Spreckels and Miss Louise Spreckels, in “Kilauea Kauai: Special to the Advertiser” and “Miss Spreckels at Koolau School,” in “News of the Islands.” Honolulu, Hawaii: The Honolulu Advertiser, 17 January 1924.

- “Samuel Transue,” in “Hardesty Sandusky County Ohio Civil War Sketches 1885.” Fremont, Ohio: Rutherford B. Hayes Presidential Library & Museums, 1885 (retrieved online, March 2021).

- Snyder, Mathias, Elisabeth, Nickolas, and Maria, in New York State Census (Albany, Albany County, New York, 1870). Albany, New York: New York State Archives.

- Strauss, Paul, in U.S. Census (Chelsea, Kennebec County, Maine 1880). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Strauss, Paul and Lizzie Norton, in Marriage Records (Waterville, Kennebec County, Maine, 9 May 1882). Augusta, Maine: Kennebec County Courthouse.

- Strauss, Paul, Lizzie and Rosa, in U.S. Census (Albion, Kennebec County, Maine 1900). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- “Taps Sound for Civil War Veteran: Washington A. Power Died Monday After a Brief Illness.” Golden, Colorado: The Colorado Transcript, 10 September 1908.

- “The 1870s,” in “Archives: Historical Timeline.” Golden, Colorado: Jefferson County, retrieved online 8 January 2025.

- “The Freedmen’s Bureau,” in “African American Heritage.” Washington, D.C.: U.S National Archives and Records Administration, retrieved online 23 January 2025.

- “The Homestead Act.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Park Service, retrieved online 25 January 2025.

- “The Homestead Act of 1862,” in “Educator Resources.” Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, retrieved online 23 January 2025.

- Theodore Mink, in Adam Forepaugh’s Museum, Menagerie and Circus, Season 1878, and in Great Forepaugh Show, Season 1883. Stratford, Connecticut: Circus Historical Society, retrieved online 23 June 2017.

- Thomas, Robert (Red). “I Played Baseball on the Herbrand Team in Old Industrial League.” Fremont, Ohio: Fremont Daily Messenger, 31 August 1927.

- “Up In Perry” (notice of Ephraim Clouser’s arrest and sanity hearing). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Harrisburg Telegraph, 22 September 1892.

- Wm. M. Hendricks, in “Borough Election” (also “Election” or “The Borough Election”). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 23 March 1861, 23 February 1867, and 20 February 1874.

- Wm. M. Hendricks, in “Court Proceedings” (notice of his assistance in transporting prisoners to the penitentiary in Philadelphia). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 17 August 1872.

- Wm. M. Hendricks, in “Local Affairs” (notice of Governor’s appointment of James Beard to take over William Hendricks’ job as justice of the peace, following Hendricks’ death). Sunbury, Pennsylvania: Sunbury American, 2 July 1875.

You must be logged in to post a comment.