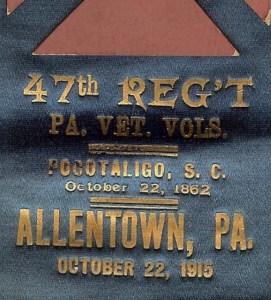

William H. Kramer was the designated honoree of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ annual reunion in 1915 (regimental reunion button, public domain).

“His run between Allentown and Harrisburg brought him in contact with many men and many lifelong friendships were formed. His whole period of service with the company extended through 48 years and 8 months.”

— The Morning Call, 17 April 1926

Formative Years

Born in the village of Cedarville, South Whitehall Township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania on 26 May 1845, William H. Kramer was a son of native Pennsylvanians John Kramer (1812-1884) and Salome (Brinker) Kramer (1811-1883). Their surname was also often spelled as “Krämer” when published in German language newspapers of the Lehigh Valley during the early to mid-nineteenth century.

William Kramer was raised and educated in the public schools of Lehigh County with his siblings: Clarissa Kramer (1834-1913), who was born in Trexlertown, Lehigh County on 17 March 1834, was known to family and friends as “Clara” and later wed James Cook, before marrying Daniel Johannes Reinhard (1837-1916); Francis Kramer (1837-1904), who was born in 1837 and later wed Sarah Ann Hoyt (1835-1907); Solomon H. Kramer (1838-1913), who was born in Cedarville on 27 June 1838 and later became a tailor’s apprentice who subsequently worked at his trade until he enlisted with the 1st and 128th Pennsylvania Volunteers during the American Civil War and who married Amanda Schaffer (1843-1932); Unknown Kramer, a daughter who was born circa 1840 and was listed (illegibly) on the 1850 federal census, but did not appear on the 1860 federal census as a child of John and Salome Kramer, signaling that she married or died before that 1860 census was conducted; Mary Ann E. Kramer (1847-1935), who remained single throughout her entire life; and Sarah Rebecca Kramer (1849-1914), who was born in Cetronia, Lehigh County on 15 May 1849 and later wed Abraham Babp (1837-1929).

In 1850, William Kramer resided with his parents and siblings in South Whitehall Township, where his father was employed as a blacksmith. After completing his education William helped his father with the operation of their family farm.

By 1860, however, he appears to have moved out of his family’s home to begin his own life because he was not listed as one of the children still living with John and Salome Kramer on the 1860 federal census. As that year came to a close and a New Year dawned, his horizons darkened — as they did for so many other Americans — when the United States of America was shaken by a secession crisis that quickly devolved into a disastrous civil war.

American Civil War

As the American Civil War raged on into its second year, William H. Kramer joined the fight to preserve America’s union by enrolling for military service in the city of Allentown on 31 August 1862. He then officially mustered in for duty at Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County on 10 September 1862 as a private with Company G of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. Military records at the time described him as an eighteen-year-old farmer who resided in Lehigh County.

Transported to New York City by train, he then received one week of basic light infantry training at Fort Hamilton before he was transported south by ship to join his regiment at its duty station in South Carolina. In reality, his service with his regiment actually began on 13 October 1862 — the date on which he finally connected with his company, according to regimental muster rolls. The mood of his new comrades was relatively upbeat, largely due to the fact that more than half of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers had just participated in a successful engagement with the enemy that resulted in the capture of Saint John’s Bluff in Florida. In addition, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was also making history at that moment because it was in the process of becoming an integrated regiment, adding to its muster rolls several Black men who had escaped chattel enslavement from plantations near Beaufort, South Carolina, including Bristor Gethers, Abraham Jassum and Edward Jassum.

Just over a week later, however, the mood was far different.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

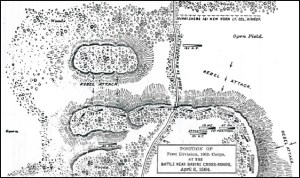

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army map of the Coosawhatchie-Pocotaligo Expedition, 22 October 1862 (public domain).

From 21-23 October 1862, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers joined with other Union troops in engaging heavily protected Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina, including at the Frampton Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge, a piece of railroad infrastructure that was playing a key role in the Confederate States Army’s movement of troops and supplies throughout the region.

Harried by snipers while en route to destroy the bridge, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers also met resistance from Confederate artillerymen who opened fire as they entered an open cotton field. Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered rifle and cannon fire from the surrounding forests. But they refused to give in. Grappling with Rebel troops wherever they found them, they pursued the Confederate troops into a four-mile retreat back to the bridge. Once there, the 47th Pennsylvania relieved the 7th Connecticut.

The engagement proved to be a costly one for the 47th Pennsylvania, however, with multiple members of the regiment killed instantly or so grievously wounded that they died the next day or within weeks of the battle. Among those killed in action was Captain Charles Mickley of Company G; one of the mortally wounded was K Company Captain George Junker.

According to Allentown’s Morning Call newspaper, “Captain Mickley was shot dead through the head within a short distance of where comrade Kramer [Private William H. Kramer] was standing.” Unfortunately for Private Kramer, he was standing close enough to Captain Mickley at that moment that he also became a target of a Confederate rifleman. Unlike his company’s better-trained captain, however, the inexperienced private was only “slightly wounded,” according to accounts that he later gave of his time in the army. In reality, he had sustained wounds to both sides of his torso. After receiving medical treatment by a regimental physician, Private Kramer was authorized to return to active duty.

Back at the Union’s base of operations on Hilton Head Island in South Carolina by 23 October, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers mourned their lost friends and tried to heal from the physical and mental trauma they had sustained. Just over a week later, several members of the regiment were called upon to serve as the funeral honor guard for Major-General Ormsby M. Mitchel, commander of the U.S. Army’s Tenth Corps (X Corps) and Department of the South, who had died from yellow fever on 30 October.

USS Seminole and USS Ellen accompanied by transports (left to right: Belvidere, McClellan, Boston, Delaware, and Cosmopolitan) at Wassau Sound, Georgia (circa January 1862, Harper’s Weekly, public domain).

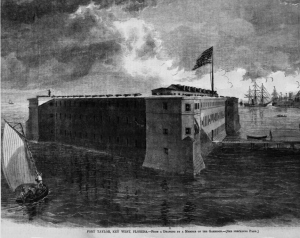

Having been ordered to head for Key West, Florida on 15 November 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would spend the coming year guarding two key federal installations Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor in Key West, while the men from Companies D, F, H, and K were assigned to protect Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the southern coast of Florida.

After packing their belongings at their Beaufort, South Carolina encampment and loading their equipment onto the U.S. Steamer Cosmopolitan, the officers and enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry sailed toward the mouth of the Broad River on 15 December 1862, and anchored briefly at Port Royal Harbor in order to allow the regiment’s medical director, Elisha W. Baily, M.D., and members of the regiment who had recuperated enough from their Pocotaligo-related battle injuries, to rejoin the regiment.

At 5 p.m. that same evening, the regiment sailed for Florida, during what was described by several members of the 47th as a treacherous and nerve-wracking voyage. According to historian Lewis Schmidt, the ship’s captain “steered a course along the coast of Florida for most of the voyage,” which made the voyage more precarious “because of all the reefs.” On 16 December, “the second night, the ship was jarred as it ran aground on one during a storm, but broke free, and finally steered a course further from shore, out in the Gulf Stream.”

In a letter penned to the Sunbury American on 21 December, Company C soldier Henry Wharton provided the following details about the regiment’s trip:

On the passage down, we ran along almost the whole coast of Florida. Rather all dangerous ground, and the reefs are no playthings. We were jarred considerably by running on one, and not liking the sensation our course was altered for the Gulf Stream. We had heavy sea all the time. I had often heard of ‘waves as big as a house,’ and thought it was a sailors yarn, but I have seen ’em and am perfectly satisfied; so now, not having a nautical turn of mind, I prefer our movements being done on terra firma, and leave old neptune to those who have more desire for his better acquaintance. A nearer chance of a shipwreck never took place than ours, and it was only through Providence that we were saved. The Cosmopolitan is a good riverboat, but to send her to sea, loadened [sic, loaded] with U.S. troops is a shame, and looks as though those in authority wish to get clear of soldiers in another way than that of battle. There was some sea sickness on our passage; several of the boys ‘casting up their accounts’ on the wrong side of the ledger.

Woodcut depicting the harsh climate at Fort Taylor in Key West, Florida during the Civil War (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

According to Corporal George Nichols of Company E, “When we got to Key West the Steamer had Six foot of water in her hole [sic, hold]. Waves Mountain High and nothing but an old river Steamer. With Eleven hundred Men on I looked for her to go to the Bottom Every Minute.”

Although the Cosmopolitan arrived at Key West Harbor on Thursday, 18 December, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers did not set foot on Florida soil until noon the next day. The men from Companies C and I were immediately marched to Fort Taylor, while the men from Companies B and E were assigned to older barracks that had previously been erected by the U.S. Army. Members of Companies A and G were marched to the newer “Lighthouse Barracks” located on “Lighthouse Key.”

On Saturday, 21 December, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, the regiment’s second-in-command, sailed away aboard the Cosmopolitan with the men from Companies D, F, H, and K, and headed south to Fort Jefferson, roughly seventy miles off the coast of Florida (in the Gulf of Mexico) to assume garrison duties there. According to Musician Henry Wharton:

We landed here [Fort Taylor] on last Thursday at noon, and immediately marched to quarters. Company I. and C., in Fort Taylor, Company E. and B. in the old Barracks, and A. and G. in the new Barracks. Lieut. Col. Alexander, with the other four companies proceeded to Tortugas, Col. Good having command of all the forces in and around Key West. Our regiment relieved the 90th Regiment N. Y. Vols. Col. Joseph Morgan, who will proceed to Hilton Head to report to the General commanding. His actions have been severely criticized by the people, but, as it is in bad taste to say anything against ones superiors, I merely mention, judging from the expression of the citizens, they were very glad of the return of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers….

1863 — Diminishing Florida’s Role as the “Supplier of the Confederacy”

Stationed in Florida for the entire year of 1863, Private William H. Kramer and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were literally ordered to “hold the fort.” Their primary duty was to prevent foreign powers from assisting the Confederate Army and Navy in gaining control over federal installations and other territories across the Deep South. In addition, the regiment was also called upon to play an ongoing role in weakening Florida’s ability to supply and transport food and troops throughout areas held by the Confederate States of America.

Prior to intervention by the Union Army and Navy, the owners of plantations, livestock ranches and fisheries, as well as the operators of smaller family farms across Florida, had been able to consistently furnish beef and pork, fish, fruits, and vegetables to Confederate troops stationed throughout the Deep South during the first year of the American Civil War. Large herds of cattle were raised near Fort Myers, for example, while orchard owners in the Saint John’s River area were actively engaged in cultivating sizeable orange groves. (Other types of citrus trees were found growing throughout more rural areas of the state.)

Florida was also a major producer of salt, which was used as a preservative for food. Consequently, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and other Union troops across Florida were ordered to capture or destroy salt manufacturing plants in order to further curtail the enemy’s access to food.

But they were performing their duties in often dangerous conditions. The weather was frequently hot and humid as spring turned to summer, mosquitos and other insects were an ever-present annoyance (and a serious threat when they were carrying tropical diseases), and there were also scorpions and snakes that put the health of Private Kramer and his comrades at further risk. In addition, there was a serious shortage of clean water for drinking and bathing.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers experienced yet another significant change when members of the regiment were ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858, following the federal government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. In response, Company A Captain Richard Graeffe and a detachment of his subordinates traveled north, captured the fort and began conducting cattle raids to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across the region. They subsequently turned their fort not only into their base of operations, but into a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops.

Red River Campaign

Map of key 1864 Red River Campaign locations, showing the battle sites of Sabine Cross Roads, Pleasant Hill and Mansura in relation to the Union’s occupation sites at Alexandria, Grand Ecore, Morganza, and New Orleans (excerpt from Dickinson College/U.S. Library of Congress map, public domain).

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer, the Charles Thomas, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by the men from Companies E, F, G, and H.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost-fully-reunited-regiment moved by train to Brashear City (now Morgan City), before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the 19th Corps (XIX) of the United States’ Army of the Gulf, and became the only regiment from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to serve in the Red River Campaign commanded by Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the soldiers from Company A were assigned to detached duty while awaiting transport that enabled them to reconnect with their regiment at Alexandria, Louisiana on 9 April.)

The early days on the ground quickly woke Private William H. Kramer and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers up to just how grueling their new phase of duty would be. From 14-26 March, most members of the 47th marched for Alexandria and Natchitoches, near the top of the L-shaped state. Among the towns that the 47th Pennsylvanians passed through were New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington.

From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James Bullard, John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were officially mustered into the regiment on 22 June at Morganza, Louisiana. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “Colored Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under-Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long, harsh-climate trek, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill (now the Village of Pleasant Hill) the night of 7 April, before continuing on the next day.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the second division, sixty members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were cut down on 8 April 1864 during the intense volley of fire in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield due to its proximity to the town of Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded and dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up unto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, a former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the Union force, the men of the 47th were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

During that engagement (now known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill), the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers succeeded in recapturing a Massachusetts artillery battery that had been lost during the earlier Confederate assault. Unfortunately, the regiment’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, and its two color-bearers, Sergeants Benjamin Walls and William Pyers, were wounded. Alexander sustained wounds to both of his legs, and Walls was shot in the left shoulder as he attempted to mount the 47th Pennsylvania’s colors on caissons that had been recaptured, while Pyers was wounded as he grabbed the flag from Walls to prevent it from falling into Confederate hands.

All three survived the day, however, and continued to serve with the regiment, but many others, like K Company Sergeant Alfred Swoyer, were killed in action during those two days of chaotic fighting, or were wounded so severely that they were unable to continue the fight. (Swoyer’s final words were, “They’re coming nine deep!” Shot in the right temple shortly afterward, his body was never recovered).

Still others were captured by Confederate troops, marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as prisoners of war until they were released during a series of prisoner exchanges that began on 22 July and continued through November. At least two members of the regiment never made it out of that prison camp alive; another died at a Confederate hospital in Shreveport.

Meanwhile, as the captured 47th Pennsylvanians were being spirited away to Camp Ford, the bulk of the regiment was carrying out orders from senior Union Army leaders to head for Grand Ecore, Louisiana. Encamped there from 11-22 April, the Union soldiers engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications.

They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April. While they were in route, they were attacked again, this time, at the rear of their retreating brigade, but they were able to end the encounter quickly and move on to reach Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night (after a forty-five-mile march).

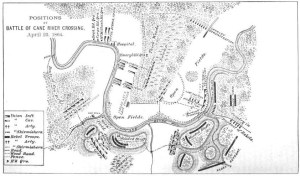

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Union Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on the Confederate Cavalry of Brigadier-General Hamilton Bee in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”).

Responding to a barrage from the Confederate Artillery’s twenty-pound Parrott guns and from enemy troops positioned atop a bluff and near a bayou, Brigadier-General Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederate troops busy while sending two other brigades to find a safe spot for the Union’s forces to cross the Cane River. As part of “the beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Smith’s artillery.

Meanwhile, additional troops under Smith’s command attacked Bee’s flank to force a Rebel retreat, and then erected a series of pontoon bridges that enabled the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. In a letter penned from Morganza, C Company Musician Henry Wharton described what had happened:

Our sojourn at Grand Score was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one for the boys, for at 10 o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty drive miles. On that day our rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d, was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebels say it ‘seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.’

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth if this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton in Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Sketches of the crib and tree dams designed by Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey to improve the water levels of the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana, spring 1864 (Joseph Bailey, “Report on the Construction of the Dam Across the Red River,” 1865, public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, they learned that they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned yet again to the hard labor of construction work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that was designed to enable Union gun boats to safely navigate the fluctuating water levels of the Red River. According to Musician Henry Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gun boats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people will eat), so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the iron clads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic, chute], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Continuing their march, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed toward Avoyelles Parish. According to Wharton:

On Sunday, May 15th, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of the Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad where with the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. — We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed into line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired, and we advanced ’till dark, when the forces halted for the night with orders to rest on their arms. ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

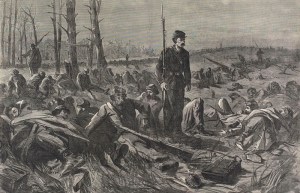

“Sleeping on Their Arms” by Winslow Homer (Harper’s Weekly, 21 May 1864).

“Resting on their arms” (half-dozing, without pitching their tents, and with their rifles right beside them), they were now positioned just outside of Marksville, on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, they reached Missoula [sic, Mansura], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic, maneuvering] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic, were] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain directly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over.– The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of the army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic, there] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Continuing on, the healthy members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. While encamped there, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the regiment in Beaufort, South Carolina (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 22-24 June.

The regiment then moved on and arrived in New Orleans in late June. On the Fourth of July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers received orders to return to the East Coast. Three days later, they began loading the regiment and its men onto ships, a process that unfolded in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I boarded the U.S. Steamer McClellan on 7 July and departed that day, while the members of Companies B, G and K, including Private William H. Kramer, remained behind, awaiting transport. They subsequently departed aboard the Blackstone, weighing anchor and sailing forth at the end of that month. Arriving in Virginia, on 28 July, the second group reconnected with the first group at Monocacy, having missed an encounter with President Abraham Lincoln and the Battle of Cool Spring at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July (a battle in which the first group of 47th Pennsylvanians had participated).

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

General Crook’s Battle Near Berryville, Virginia, 3 September 1864 (James E. Taylor, public domain).

Attached to the Middle Military Division, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah, beginning in early August of 1864, and placed under the command of Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, and also engaged over the next several weeks in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville, Middletown, Charlestown, and Winchester as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

The 47th Pennsylvania then engaged with Confederate forces in the Battle of Berryville from 3-4 September.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill

On 19 September 1864, Private William H. Kramer and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers next began a series of battles that would turn the tide of the American Civil War firmly in favor of the Union and help President Abraham Lincoln to secure re-election.

Together, with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Philip Sheridan and Brigadier-General William Emory, commander of the 19th Corps (XIX Corps), the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces in the Battle of Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and known as “Third Winchester”).

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ march toward destiny began at 2 a.m. that 19 September as the regiment left camp and joined up with other regiments in the Union’s 19th Corps. Advancing from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps bogged down for several hours as Union wagon trains made their way slowly across the terrain. As a result, Early’s troops were able to dig in and wait.

The fighting, which began at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery that was positioned on higher ground.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and other 19th Corps regiments were directed by Brigadier-General William Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as a Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops that were trying to cross clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units that were led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice (once in the chest), was mortally wounded.

The 47th Pennsylvania subsequently opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of Brigadier-General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank. As the 19th Corps began pushing the Confederates back, with the 47th Pennsylvania in the thick of the fight, Early’s “grays” retreated.

Sheridan’s “blue jackets” ultimately went on to win the day.

Leaving twenty-five hundred wounded behind, the Rebels retreated to Fisher’s Hill, eight miles south of Winchester, where a second engagement, the Battle of Fisher’s Hill, was waged from 21-22 September. Following a successful morning flanking attack by Sheridan’s Union forces, which outnumbered Early’s Confederate troops three to one, Early’s troops fled to Waynesboro, but were pursued by the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments. Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvanians made camp at Cedar Creek.

They would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but they would do so without their two most senior leaders, Colonel Tilghman H. Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, who mustered out from 23-24 September, upon expiration of their respective terms of service. Fortunately, they were replaced by leaders who were equally respected for their front-line experience and temperament, including Major John Peter Shindel Gobin, formerly of Company C, who had been promoted up through the regimental officers’ corps to the regiment’s central command staff (and who would be promoted again on 4 November to the rank of lieutenant-colonel and appointed as the 47th Pennsylvania’s final commanding officer).

Battle of Cedar Creek

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

During the fall of 1864, Major-General Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s farming infrastructure. Viewed today through the lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed the lives of many innocent civilians, whose lives were uprooted or even cut short by the inability to find food or adequate shelter. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864.

Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederates began peeling off in ever greater numbers as the battle wore on in order to search for food to ease their gnawing hunger, thus enabling Sheridan’s well-fed troops to rally and, once again, to win the day.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive show of the Union’s might. From a human perspective, it was both inspiring and heartbreaking. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles, all while pushing seven Union divisions back.

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

But then “The men were aroused to the highest pitch of enthusiasm by the exploits of their dashing leader, General Phil Sheridan,” according to Allentown’s Morning Call newspaper. Historian Samuel P. Bates later described that epic battle, noting that:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers as he rode rapidly past them – ‘Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!'”

Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas, who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. But the day had proven to be a particularly costly one for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

The regiment lost the equivalent of two full companies of men in killed, wounded and missing, as well as soldiers who were captured by Rebel troops and dragged off to prisoner of war (POW) camps, including the Confederates’ Libby Prison in Virginia, the notorious Salisbury Prison in North Carolina and the hellhole known as “Andersonville” in Georgia. Subjected to harsh treatment at the latter two, many of the 47th Pennsylvanians confined there never made it out alive. Those who did either died soon after their release, or lived lives that were greatly reduced in quality by their damaged health.

Following those major battles, Private William H. Kramer and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered to march to Camp Russell near Winchester, where they rested and began the long recovery process from their physical and mental wounds. Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th was then ordered to outpost and railroad guard duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia five days before Christmas.

1865 — 1866

Still stationed at Camp Fairview as the New Year progressed, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers continued to patrol key Union railroad lines in the vicinity of Charlestown and chase down Confederate guerrillas who had repeatedly attempted to disrupt railroad operations and kill soldiers from other Union regiments. During this phase of duty, they were re-assigned to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah in February 1865, and continued to perform those same duties until late March, when they were ordered to head back to Washington, D.C., by way of Winchester and Kernstown, Virginia.

Joyous News and Then Tragedy

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As April 1865 opened, the battles between the Army of the United States and the Confederate States Army intensified, finally reaching the decisive moment when the Confederate troops of General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on 9 April.

The long war, it seemed, was finally over. Less than a week later, however, the fragile peace was threatened when an assassin’s bullet ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln. Shot while attending an evening performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre on 14 April 1865, he died from his head wound at 7:22 a.m. the next morning.

Shocked, and devastated by the news, which was received at their Fort Stevens encampment, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were given little time to mourn their beloved commander-in-chief before they were ordered to grab their weapons and move into the regiment’s assigned position, from which it helped to protect the nation’s capital and thwart any attempt by Confederate soldiers and their sympathizers to re-ignite the flames of civil war that had finally been stamped out.

So key was their assignment that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were not even allowed to march in the funeral procession of their slain leader. Instead, they took part in a memorial service with other members of their brigade that was officiated by the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental chaplain, the Reverend William D. C. Rodrock.

Unidentified Union infantry regiment, Camp Brightwood, Washington, D.C., circa 1865 (public domain).

Present-day researchers who read letters sent by 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to family and friends back home in Pennsylvania during this period, or post-war interviews conducted by newspaper reporters with veterans of the regiment in later years, will learn that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were collectively heartbroken by Lincoln’s death and deeply angry at those whose actions had culminated in his murder. Researchers will also learn that at least one member of the regiment, C Company Drummer Samuel Hunter Pyers, was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train, while other members of the regiment were assigned to guard duty at the prison where the key assassination conspirators were being held during the early days of their imprisonment and trial, which began on 9 May 1865. The regiment was headquartered at Camp Brightwood during this period.

Attached to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were permitted to march in the Union’s Grand Review of the National Armies, which took place in Washington, D.C. on 23 May.

On 1 June 1865, Private William H. Kramer was honorably discharged from the military at Camp Brightwood, by General Orders, No. 53.

Return to Civilian Life

A Philadelphia & Reading Railroad train shown departing from the East Penn Junction near Allentown, Pennsylvania, 1905 (public domain; click to enlarge).

Following his honorable discharge from the military, William H. Kramer returned home to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, where he tried to regain some semblance of a normal life after all that he had experienced during the war. A resident of Allentown, he was hired by the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad (P. & R.) in September 1866, beginning what would become a nearly half-century-long career with that railroad company, which also became known as the “Reading Railroad,” or “Reading Lines,” and, during the 1890s, as the “Reading Company.” Initially employed as a baggage master at the P. & R.’s East Penn Junction station, he was subsequently rewarded for his dedication and attentive service to railroad passengers through several promotions, including to the position of brakeman on the P. & R.’s East Penn railroad line, and then, in 1869, to the position of conductor on a P. & R. passenger train line. According to Allentown’s Morning Call newspaper:

His run between Allentown and Harrisburg brought him in contact with many men and many lifelong friendships were formed. His whole period of service with the company extended through 48 years and 8 months.

During that phase of William H. Kramer’s life, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania “became a crossroads, with four major trunk lines linking the East Coast to western states (Pennsylvania Railroad, Baltimore and Ohio, New York Central, and Erie), and others linking Canada and northern states through Pittsburgh and Philadelphia to the states to the south,” according to historians at the Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. “Founded in 1846 as purely an in-state line, the Philadelphia-based Pennsylvania Railroad became the nation’s single most important railroad, carrying 10 percent of all freight in America and 20 percent of all passengers. In 1880, with 30,000 employees and $400 million in capital, it was the nation’s largest corporation.

Railroads even regulated the pace of life. Standard time zones, established by the railroads in 1883, replaced the fragmented system by which, as a PRR timetable once explained, “Philadelphia local time” is seven minutes faster than Harrisburg time, thirteen minutes faster than Altoona time, and nineteen minutes faster than Pittsburgh time.”

Married in early 1866 to Matilda E. Denhard (1848-1935), an Allentown native who was a daughter of Charles and Alawissa (Scholl) Denhard, William H. Kramer and his wife subsequently welcomed the births of: Annie Kramer (1866-1961), who was born on 10 December 1866 and later wed and was widowed by Milton Bleiler (1849-1926); Mary Alice Kramer (1868-1940), who was born in Allentown on 13 March 1868 and later wed Henry W. Hartman (1866-1952); and Charles H. Kramer (1870-1953), who was born on 6 April 1870, married Mazie A. Mohry (1871-1934) and became a plumber and city plumbing inspector for his hometown.

Railroad tracks near the Topton Furnace, Longswamp Township, Berks County, Pennsylvania, circa 1890s (public domain; click to enlarge).

Still employed as a conductor throughout the 1880s and 1890s, William H. Kramer had a close call on the job on 4 November 1897 when the P. & R. passenger train on which he was working — the East Penn No. 4 — “ran into an open switch at the Topton furnace and was partly wrecked” that morning during an accident that was caused by the neglience of the other train’s brakeman. According to The Morning Call:

Barney Reilly, of South Allentown, the fireman, and Harry Knecht, an express messenger, were seriously injured and Benjamin Klemmer, of Reading, the engineer, slightly injured. The train was in charge of Conductor William H. Kramer, of this city, and was drawn by engine No. 597. Harry Wunder is the baggagemaster and Howard Esch the brakeman.

The wreck occurred about half-past 9 o’clock and was caused through the negligence of the brakeman of freight train No. 81, who left the switch open after the shifter had backed into a sliding to wait for the passenger train, which was due to pass. When the passenger train came along at full speed it ran into the open switch and crashed into the freight train. The two engines came together with a terrible crash and were almost completely telescoped.

Fireman Reilly was shoveling coal at the time and was thrown into the firebox of the engine. His body was pinned between the tank and the cab by the coal, which was thrown forward, and it was necessary to get another engine to pull away the tender before he could be released. Reilly was badly bruised and scalded about the face, hands and legs and also suffered internal injuries.

Harry Knecht, the messenger, was caught in the wrecked car and sustained a severe gash over the eye and a cut in the head.

Engineer Klemmer escaped serious injury, but had several teeth knocked out.

The passengers were badly shaken up, but none of them were hurt. Fireman Reilly and Express Messenger Knecht were brought in on the noon train and were taken to their respective homes.

Clerk Carr was injured at the left arm and hip. As the crash came he was knocked down and rolled under the table. When the car lay on the side he jumped out. The mail matter was soaked by the burst tank but he saved it all. At first he thought he was not hurt, but he is unable to work. Dr. J. D. Christman attends him.

The engineer of the freight engine was Daniel Klemmer, a brother to the passenger engineer.

But that accident did not end or even derail his career. In May 1910, William H. Kramer was “made conductor of the new Harrisburg special which was put into service … by the P. & R. R. R. Co,” according to The Allentown Democrat, which which noted that that particular train had made records for itself” earlier that month “making the run from New York to Harrisburg in four hours,” beating “the Penna. Special record by forty minutes.”

Retired on 3 May 1913, due to the P. & R.’s age-related retirement rules, William H. Kramer was rewarded for his service to the company with a solid railroad pension.

Bottom half of the ribbon designed for the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers’ annual reunion in 1915, which honored William H. Kramer, who served with the regiment’s G Company (public domain).

An active member of the Grand Army of the Republic (G.A.R.), he served as a vice commander of the G.A.R.’s Department of Pennsylvania and as the commander of the E. B. Young Post (No. 87), and was also a president of the 47th Pennsylvania Regiment Association. In addition, he was an active member of the Reading Railroad Relief Association, Grace United Evangelical Church, the Knights of Malta (charter member of the St. Alban Commandery, No. 46), and the Knights of the Golden Eagle (Allentown Castle, No. 55). And, at some point during his work years, he also served as a member of the common council in Allentown, during which time he represented constituents of the Seventh Ward, according to at least one newspaper’s synopsis of his life.

In 1915, his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers paid tribute to him by naming him as the designated honoree for the regiment’s annual reunion. Held in the Sons of Veterans’ Hall at Eighth and Turner Streets in Allentown on 22 October of that year — the fifty-third anniversary of the Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina (a battle in which William Kramer had been wounded as a private serving with the 47th Pennsylvania’s G Company) — the event was well attended, and was presided over by William H. Kramer in his capacity as the retiring president of the 47th Pennsylvania’s veterans’ association. According to The Allentown Leader:

Flowers were presented to each veteran by Mrs. Annie E. Leisenring, widow of Captain Thomas Leisenring, who commanded Company G of the 47th.

Prayer was offered by Rev. T. Asher Hess of Philadelphia, and the response was made by Squire William H. Glace of Catasauqua.

The Committee on Election reported for new officers as follows: President, Squire William H. Glace; vice-president, Captain W. H. Bartholomew, Allentown; secretary, Daniel Tombler, Easton; chaplain, Rev. T. Asher Hess; assistant chaplain, William Adams; treasurer, Colonel Francis Daeufer.

The formal address of the day was made by Congressman Arthur G. Dewalt. Dinner was served at the Lafayette Hotel, at which Captain Schaadt spoke on the history he is writing of the regiment.

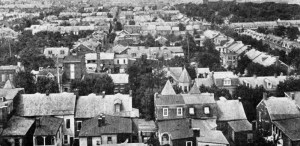

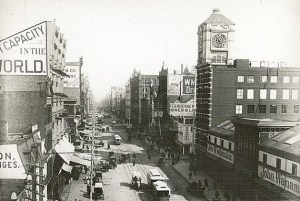

Rooftop view from Diehl’s Furniture, 8th and Turner Streets, Allentown, Pennsylvania, looking west, 1910 (public domain; click to enlarge).

A more detailed report was also published by The Allentown Democrat:

Perhaps the pleasantest reunion of the survivors of the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, in many years was that held yesterday in the rooms of the Allen Camp, No. 6, Sons of Veterans. The attendance was one of the largest in recent years and the pleasure in recounting the days of half a century ago among the minutest.

One of the striking features of the reunion was the report of the small number of deaths during the past year, but two having gone before. The year previous and the one before that were prolific with deaths of the veterans.

The gathering was devoid of any ostentation, the men simply wishing to gather together perhaps for the last time and dwell in fellowship and transact their business without any gusto. Heretofore drums beat their way in parade and it was made a holiday by citizens of the various meeting places. All this has been done away with and hereafter all the meetings will be held quietly in this city, where the largest number of survivors exist. The men got together to the number of a hundred, heard speeches and had dinner and then went their way again for another twelve months. But the brief sessions were fraught with the greatest interest.

President Wm. H. Kramer presided at the gathering and directed the business. Mayor C. W. Rinn, the grandson of a veteran, delivered the address of welcome and he did it feelingly, for his ancestor was a member of the regiment. Sergeant Wm. H. Glace, of Co. F, Catasauqua, made an appropriate response, during which he reviewed the battle of Pocotaligo, where the men had their baptism of fire.

Rev. T. Asher Hess, of Philadelphia, the drummer boy of the 128th Regiment who is an honorary member of the association, made one of his patriotic addresses and was followed by Congressman A. G. Dewalt, who dwelt at some length on the service of the men during the war.

Frank Leffler, Edward Keiper, Lieut. J. B. Stuber, William Adams and D. G. Gearhart [sic, “Gerhart”] were a nominating committee, who reported their selection of these officers: President, W. H. Glace; vice president, Capt. W. H. Bartholomew; secretary, David Tombler; treasurer, Francis Daeufer; chaplain, Rev. T. A. Hess; assistant chaplain, William Adams.

Following the meeting the veterans marched around the monument with bared heads and went to the Lafayette Hotel, where they partook of an appetizing dinner. During its course, Capt. James L. Schaadt brought to the attention of the veterans the importance of writing the history of the regiment and he with a corps of editors will do the work should the veterans place the material in their hands. Captain Schaadt recalled old deeds when he read for the first time since its delivery, the speech of Col. T. H. Good when the good people of Key West presented him with a gold sword as a tribute of their appreciation of his management of the military affairs at that important post in 1861 [sic, “1863”]. The speech made by Mayor Cole is also preserved and was read also. It was the source of renewed interest in the affairs of the regiment and many incidents were recalled in consequence. These will be preserved and reserved for the history. It was related for the first time how private Frank King, of Co. F. of Catasauqua, alone captured Gen. Robert Taylor’s flag at the headquarters at Sabine Cross Roads during the Red River expedition, the record of which is now preserved in the archives at Washington. The story was also told for the first time how Sergeant Wm. H. Glace’s life was saved by a providential intervention of orders.

The reunion was the forty-third and the badges bore the picture of President Wm. H. Kramer. Only one original officer of the regiment remains in Lieut. James B. Stuber, of Co. I, who was present at the reunion.

As in recent years Mrs. Annie E. Leisenring, widow of Captain Thomas B. Leisenring, of Co. G, presented the survivors with carnations. Miss Hattie Good, daughter of the late Frank P. Good, also sent carnations.

One of the interested veterans in attendance was Uriah Boston, of Co. D, who ran away from the Millerburg academy [sic, “Millersburg Academy”] when 15 years of age and enlisted for service. He also did secret service duty for the government for two years during the Spanish-American war. He has been with the government secret service for the past 14 years. He is hale and hearty and enjoyed the reunion immensely.

Among the ladies present were Mrs. Leisenring, Mrs. M. P. Kerschner, Mrs. Annie E. Swartz, Mrs. George Longenhagen, Mrs. D. A. Tombler and Miss E. Schalmant, of Philadelphia.

Two deaths were reported during the year. They were George Mull [sic, ” Moll”], of Co. F, and William Swartz, of Co. I.

The following were present:

Co. A — Reuben Rader, Max Schlemmer.

Co. B — Thom. Cope, Andrew Osman [sic, “Osmun”], D. G. Gerhard [sic, “Gerhart”], and Casper Shriner [sic, “Schreiner”].

Co. D — Uriah Boston.

Co. E — Henry Coburn and William Adams.

Co. F — D. A. Tombler, Allen Miller, William H. Bartholomew, Ed. Reinsheimer [sic, “Rensimer”], Reuben Keim, William Erich, George Longenhagen, Walter Van Dyke, Frank H. Wilson and William H. Glace.

Co. G — William H. Kramer, B. F. Swartz, B. S. Koons, Solomon Hillegass, M. H. Heckman [sic, “Hackman”], Charles Heckman [sic, “Hackman”] and Henry Doll.

Co. I — Francis Daeufer, Jefferson Kunkle, Sylvester McCabe [sic, “McCape”], George H. Dech, Tilghman Dech, W. F. Henry, Ed. Keiper, Frank Leffler, James B. Stuber, Israel Troxel [sic, ” Troxell”] and Henry Wieser.

Co. K — Tilghman Bogert [sic, “Boger”], Samuel Reinhart [sic, “Reinert”], Walter Handwerk, and Henry Savitz.

Rooftop view from Diehl’s Furniture, 8th and Turner Streets, Allentown, Pennsylvania, looking northeast, 1910 (public domain; click to enlarge).

But it was Allentown’s Morning Call that provided an account that seemed to best capture the spirit of that year’s reunion:

These occasions are annually looked forward to with the fondest anticipation by the veterans as the one time of the year when they can meet and greet one another again and renew the ties that were formed in the service of their country whose integrity they enlisted to defend and uphold. The men are growing fewer in number year by year. The relentless hand of death was unusually sparing during the past year and the fatal asterisk of death was appended to the names of only two comrades since the men met last year.

But the ravages of the years are becoming more apparent as the years roll on. Locks are becoming whiter. Eyes are dimming. Hearing is not quite so acute. The steps are beginning to falter. But the ardor is not cooled nor is their patriotism quenched. It is an inspiration to see these aged men as they meet once a year and greet each other and swap stories of the war in which they fought and in which they made so many sacrifices.

Each year something new crops up. Yesterday William H. Glace learned from Uriah Boston, of Washington, D.C., who is now a member of the secret service that his life was saved by the countermanding of an order. Mr. Boston, who came from Lancaster, and who enlisted in Company D, and who has also served in the Spanish-American war, told him that had he (Mr. Glace) gone on an errand on which he was sent by Col. Good, he would not be here to meet his comrades. Mr. Glace had been ordered to go from the camp of the Forty-seventh in Louisiana to New Orleans by steamer to get a fresh supply of muster rolls. But before he had started the order was recalled and a sergeant of Company D was sent instead. The vessel had hardly gotten under way than the Rebels fired upon it and the boat was sunk and all on board perished.

Sergeant Longenhagen also recalled how at Sabine Cross Roads in Louisiana, at dusk one evening he and Mr. Glace captured one of the aides of General Dick Taylor, who was a son of the former president, Zachary Taylor.

It was also related that at the battle of Sabine Cross Roads the late George King in the heat of the fight went up to the color bearer of the battle flag of General Taylor and took the standard from his hands and returned with it to the ranks of the regiment and the record of the heroic act was sent on to the War Department by the colonel.

The veterans met yesterday at 11 a.m. in the hall of the Sons of Veterans, where they had comfortable quarters and where they were enabled to transact their business. William H. Kramer, of this city, the veteran retired Reading Railway conductor, presided.

In 1924, William H. Kramer and his wife relocated to the community of Emaus in Lehigh County, and resided at 132 North Fourth Street.

Illness, Death and Interment

Gravestone of Private William H. Kramer, Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Greenwood Cemetery, Allentown, Pennsylvania (public domain).

Ailing and confined to his bed for the final two weeks of his life, William H. Kramer died at his home in Emaus at 2:30 in the morning on 16 April 1926. A month shy of his eighty-first birthday at the time of his passing, he was laid to rest in the soldiers’ section of the Greenwood Cemetery in Allentown.

What Happened to William H. Kramer’s Parents?

By 1870, William H. Kramer’s parents, John and Salome (Brinker) Kramer, were residing in Allentown’s Fifth Ward with their daughter, Sarah (William’s sister). According to a federal census enumerator, John Kramer supported his family on the wages of a laborer who had amassed real estate that was valued at two thousand dollars (the equivalent of slightly less than fifty thousand U.S. dollars in 2025). Still employed as a laborer by 1880, John Kramer was living in Salisbury Township, Lehigh County with his wife and daughter, Mary A. Kramer (William’s sister), at the time that an enumerator interviewed him in early June; however, neither of William Kramer’s parents would live to witness the dawn of another new decade. Salome (Brinker) Kramer died in Salisbury Township at the age of seventy-one, on 23 January 1883, and was subsequently laid to rest at the Fairview Cemetery in Allentown. John Kramer then passed away in Salisbury Township at the age of seventy-one, on 27 March 1884, and was laid to rest beside her at that same cemetery.

What Happened to William H. Kramer’s Siblings?

Sometime during the late 1860s or early 1870s, William H. Kramer’s brother, Francis Kramer (1837-1904), migrated west to the town of Wooster in Wayne County, Ohio, where he became a barber and married Wooster native Sarah Ann Hoyt, who was a daughter of John Hoyt, one of Wooster’s early settlers. Following his sudden death in his adopted hometown on 7 November 1904, he was laid to rest at the Wooster Cemetery.

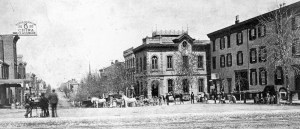

Center Square at 7th Street (Allen House Hotel at right; Allentown Bank and Board of Trade, looking north, top), Allentown, Pennsylvania 1876 (public domain; click to enlarge).

Meanwhile, William Kramer’s other siblings were forging their own paths in life. William Kramer’s older sister, Clarissa Kramer, married James Cook and settled with him in Lehigh County, where they welcomed the arrival of a son, Charles F. Cook (1855-1935), who was born in Cetronia on 29 October 1855 and later grew up to become an employee of the Philadelphia & Reading Railroad like his uncle, William H. Kramer. Subsequently widowed by her husband, Clara (Kramer) Cook then wed Daniel Johannes Reinhard, and welcomed the Allentown births with her second husband of six children: Anna Elizabeth Reinhard (1864-1940), who was born in 1864 and later wed Benjamin Charles Marks (1860-1944); Benjamin Reinhard (1865-1943), who was born on 2 February 1865 and later wed Mary Alice Sterner (1863-1922); Mary C. Reinhard (1867-1937), who was born on 19 November 1867 and later wed Edgar Francis Fenstermacher (1869-1936) and settled with him in Allentown; Jennie M. Reinhard (1872-1929), who was born on 16 May 1872 and later wed George A. Rex (1863-1936) and settled with him in Allentown; Katie S. Reinhard (1875-1926), who was born on 22 September 1875 and later wed Harry Haley (1877-1939) and settled with him in Allentown; and William Reinhard (1870-1941), who was born on 11 April 1870 and later settled in Hamburg, Berks County. Known to family and friends as “Clara,” Clarissa (Kramer Cook) Reinhard was an active member of her church. Ailing during her final five months, she also then contracted pneumonia, which ended her life on 12 January 1913. Roughly two months shy of her seventy-ninth birthday when she passed away at her home in Allentown, Clara was laid to rest at Allentown’s Union-West End Cemetery.

William Kramer’s older brother, Solomon H. Kramer, also returned to Allentown, initially, after his own military service in the American Civil War. While there, he married Amanda Schaffer and welcomed the births with her of: Charles H. Kramer, who was born circa 1865; and Minnie Emma Kramer (1868-1964), who was born in Allentown on 2 November 1868 and would later wed and settle in Philadelphia with Conrad Anton Stuetz, before spending her final years at the Masonic Home in Elizabethtown, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania. By 1870, however, Solomon Kramer and his young family were living in the city of Philadelphia, where he found work as a hotel clerk and later became involved in the restaurant industry. While in Philadelphia, he and his wife, Amanda, welcomed the births of two more children: Laura M. Kramer (1871-1958), who was born on 4 February 1871 and would later wed Charles Edward Rieck (1863-1903); and Frank Kramer (1873-1948), who was born on 31 August 1873 and would later wed Hettie L. Kern. Sometime after the federal census of 1900 and before 1906, however, Solomon Kramer made the decision to return to Lehigh County, where he found work as a cashier at the White House Cafe in Allentown. According to the 1910 federal census, he resided in a rented home in Allentown’s Eighth Ward with his wife and their twelve-year-old granddaughter, Helen Irene Rieck. (Helen was the daughter of Solomon’s daughter, Laura M. (Kramer) Rieck, who had been widowed in 1903.) Ailing for the final year of his life, Solomon Kramer died at the age of seventy-three at his home in Allentown, on 26 February 1913. His remains were subsequently transported to the Philadelphia area for interment, according to his obituary. He now rests at the Hillside Cemetery and Memorial Gardens in Roslyn, Montgomery County, Pennsylvania.

Following her marriage to Abraham Babp circa 1872, William Kramer’s sister, Sarah Rebecca (Kramer) Babp, welcomed the Allentown births with him of: Anna Lydia Babp (1877-1948), who was born on 11 September 1877; and twin sisters Mary Rebecca Babp (1886-1892), who was born on 15 July 1886 but died at the age of six, and Martha Sarah Babp (1886-1946), who was born on 15 July 1886, went on to marry Joseph P. Murphy and passed away at the age of fifty-nine in St. Petersburg, Florida. Ailing with myocarditis during her final years, Sarah Rebecca (Kramer) Babp suffered an episode of apoplexy on 2 June 1914, which subsequently ended her life on 19 June. Following her passing in Allentown at the age of sixty-five, she was laid to rest at Allentown’s Fairview Cemetery.

William Kramer’s younger sister, Mary Ann E. Kramer, grew up to become a laborer at a shoe factory, never married and also went on to live a long life like William. Ailing with myocarditis during her final years, she died at the age of eighty-seven at 1123 Maple Street in Allentown, on 16 January 1935, and was buried at Allentown’s Fairview Cemetery.

What Happened to William H. Kramer’s Widow and Children?

World War I Victory Parade, Tenth and Hamilton Streets, Allentown, Pennsylvania, 1919 (public domain).

William H. Kramer’s widow, Matilda (Denhard) Kramer, survived him by nine years. A charter member of Allentown’s Grace Evangelical Congregational Church, she had been involved with multiple church activities throughout her life, and had also been an active member of the women’s chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic (Allen Circle, No. 10). Ailing with myocarditis, she suffered a cerebral hemorrhage on 7 October 1935 and died at the age of eighty-eight at the home of her daughter, Annie (Kramer) Bleiler, at 132 North Fourth Street in Emaus, on 13 October. She was then laid to rest beside her husband at Allentown’s Greenwood Cemetery.

William Kramer’s daughter, Annie (Kramer) Bleiler, was an active member of Allentown’s Trinity Evangelical Congegational Church. Married in 1891 to Milton Bleiler (1849-1926), a cabinetmaker who was employed by the C. A. Dorney Furniture Company in Allentown, she was widowed by him when he passed away at their home in Emaus on 12 April 1926. By the mid-1930s, she was residing with her stepdaughter, Ella J. (Bleiler) Hunsicker (1888-1966), at the Burd & Rodger Memorial Home in Myerstown, Lebanon County, Pennsylvania. Ailing with pneumonitis during the final ten days of her life, Annie (Kramer) Bleiler was admitted to the Good Samaritan Hospital in Lebanon County, where she died on 1 November 1961. Her remains were subsequently returned to Allentown for burial at the Greenwood Cemetery.

Liberty Bell Line, 8th and Hamilton, Lehigh Valley Transit Co., Allentown (circa 1938, public domain)

Following her marriage to Henry W. Hartman in 1887, William Kramer’s daughter, Mary Alice (Kramer) Hartman, and her husband welcomed the Allentown births of daughters: Florence Matilda Hartman (1890-1927), who was born on 4 October 1890, later graduated from the Allentown Hospital’s School of Nursing in 1907 and wed Joseph H. Kralowitz, before working in the Allentown office of the Pennsylvania Independent Oil Company; and Erma I. Kramer (1899-1953), who was born on 29 May 1899 and later wed and was widowed by John Earl Shaffer (1893-1939), before marrying the Reverend Ralph Charles Hillegass (1895-1970). Ailing with heart disease during the final years of her life, Mary Alice (Kramer) Hartman died at the age of seventy-two in Emaus on 4 September 1940, and was laid to rest at the Union-West End Cemetery in Allentown.

Born and raised in Allentown, William Kramer’s son, Charles H. Kramer, grew up to become a plumber’s apprentice with Birchall and Parton, before embarking on his own plumbing career, during which time he became the first plumbing inspector ever hired by the City of Allentown — a position he held until his resignation on 30 January 1934. Following his marriage to Mazie Mohry during the late 1880s, he welcomed the birth with her of: Ruth Mohry Kramer (1888-1965), who was born on 21 November 1888 and later wed Laney Raymond Schoenberger (1887-1955). A member of the Master Plumbers Association of Allentown, he was also an active member of Allentown’s Pioneer Band, the Fraternal Order of Eagles, the John Hay Republican Club, and the Orioles and Owls. Ailing with heart disease, cystitis and prostatitis during his final years, Charles H. Kramer died from disease-related complications at the age of eighty-three at the Allentown General Hospital in Allentown, on 26 June 1953, and was also interred at Allentown’s Greenwood Cemetery. At the time of his death, he was “the oldest practicing plumber” in Allentown, according to his obituary in The Morning Call.

Sources:

- “6 Railroad Workers of the Past and Present,” in “Back to Rail Lines.” Ronks, Pennsylvania: Strasburg Rail Road, 18 July 2023.

- “Annie M. Bleiler” (the first-born child of William H. Kramer), in Death Certificates (file no.: 104211-61, date of death: 1 November 1861). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- “Another War Veteran Summoned by Death: William H. Kramer, for 48 Years Employed on P. & R. R. R., Passes Away in Emaus.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 17 April 1926.

- Bates, Samuel P. History of Pennsylvania Volunteers, 1861-5, vol. 1. Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: B. Singerly, State Printer, 1869.

- “Charles Kramer, Oldest Allentown Plumber, Dies” (obituary of the youngest child of William H. Kramer). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 28 June 1953.

- Charles H. Kramer (the youngest child of William H. Kramer), in Death Certificates (file no.: 53513, registered no.: 886, date of death: 26 June 1953). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- “Cook Floral Tributes” (report on the funeral of Emma Cook, the wife of Charles F. Cook, who was a nephew of William H. Kramer and a son of Clarissa (Kramer Cook) Reinhard and her first husband, James Cook). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 26 October 1914.

- “Death in Ohio” (death notice of William H. Kramer’s brother, Francis Kramer). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Democrat, 16 November 1904.

- “East Penn Collision: A Bad Wreck at Topton Yesterday Morning at 9:30 O’Clock.” Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 5 November 1897.

- “Florence Hartman” (obituary of a granddaughter of William H. Kramer and the daughter of Mary Alice (Kramer) Hartman). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 30 May 1927.

- “Florida’s Role in the Civil War,” in Florida Memory. Tallahassee, Florida: State Archives of Florida.

- Frank Kramer (a nephew of William H. Kramer and a son of Solomon H. Kramer), in Death Certificates (file no.: 83296, registered no.: 18489, date of death: 20 September 1948). Harrisburg, Pennsylvania: Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Department of Health, Bureau of Vital Statistics.

- “Funeral of Clara Reinhard” (obituary of William H. Kramer’s older sister). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Leader, 14 January 1913.

- Grodzins, Dean and David Moss. “The U.S. Secession Crisis as a Breakdown of Democracy,” in When Democracy Breaks: Studies in Democratic Erosion and Collapse, from Ancient Athens to the Present Day (chapter 3). New York, New York: Oxford University Press, 2024.

- “John Kramer” (death notice of William H. Kramer’s father). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Allentown Democrat, 2 April 1884.

- “Kramer” (death notice of William H. Kramer’s youngest child, Charles H. Kramer). Allentown, Pennsylvania: The Morning Call, 28 June 1953.

- Kramer, John, Sarah [sic, “Salome”], Clousy [sic, “Clarissa” or “Clara”], Francis, Solomon, Morry [sic, given name unknown due to illegible handwriting on original census record; female child, aged ten, born circa 1840], William, Morey [sic, “Mary Ann E. Kramer”; female child, born in 1847], and Sarah, in U.S. Census (South Whitehall Township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, 1850). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Kramer, John (William H. Kramer’s father), Solomeh [sic, “Salome (Brinker) Kramer”] (William H. Kramer’s mother) and Mary (William H. Kramer’s sister); Brinker, Jacob (William H. Kramer’s maternal grandfather); and Kook, Charles [sic, “Charles F. Cook”] (William H. Kramer’s nephew and the first-born child of Clarissa (Kramer) Cook and her first husband, James Cook), in U.S. Census (South Whitehall, South Whitehall Township, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania, 1860). Washington, D.C.: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration.