Alternate Spellings of Surname: Good, Guth

The military headstone of Corporal Harrison Guth, Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Jordan Lutheran Cemetery, Orefield, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania (public domain).

Born in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania on 1 June 1838, Harrison Guth was a son of Nathan Guth (1811-1852) and Lydia Ann (Albright/Albrecht) Guth (1810-1847) and the brother of: Peter John Guth (1833-1894), who was born on 2 December 1833 and later wed Judith Fenstermaker (1832-1900) in 1853; Malinda Hannah Guth (1841-1897), who was born on 4 October 1841 and never married; William Henry Guth (1844-1927), who was born on 20 March 1844 and later adopted the surname spelling of “Good” and became a farmer and the husband of Mary Ann Smith (1842-1927); and Eliza Maria Guth (1848-1925), who was born in Whitehall, Lehigh County on 12 June 1848 and later wed Allen H. Bortz (1848-1926).

Orphaned by the early 1850s, after his mother, Lydia, died circa 1848 and his father, Nathan Guth, died at the age of forty in Lehigh County on 20 April 1852, fourteen-year-old Harrison Guth was forced by fate to become an adult — long before he was ready to do so.

The military headstone of Musician Daniel H. Gackenbach, Company H, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Jordan Lutheran Cemetery, Orefield, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania (public domain).

By the time he was twenty-two years old (in 1860), Harrison Guth was employed as a live-in servant at the home of the Gackenbach family (alternate surname spelling: “Gachenbach”) in Ruchsville, North Whitehall Township. The head of that family, Daniel H. Gackenbach, owned a personal estate that was valued at two thousand and fifty dollars by that year’s federal census enumerator (the equivalent of roughly eighty thousand U.S. dollars in 2025), and would go on to serve with Harrison Guth in the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry during one of the darkest periods in American History.

American Civil War

By the summer of 1861, it became clear to Harrison Guth that the American Civil War was only going to increase in intensity if the federal government could not deploy enough soldiers to bring an end to the conflict. So, he made the difficult decision to leave behind all that he knew to try to help his country. On 18 September 1861, he enrolled for military service in Allentown. He then traveled to Camp Curtin in Harrisburg, Dauphin County, where he officially mustered in for duty that same day as a private with Company G of the newly-formed 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry.

Company G was initially led by Charles Mickley, a miller and merchant who was a native of Mickleys near Whitehall Township in Lehigh County, Pennsylvania. After recruiting the men who would form the 47th Pennsylvania’s G Company, Charles Mickley had personally mustered in for duty as a corporal with the 47th Regiment, Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on 18 September 1861, and was then promptly commissioned as a captain and given command of Company G that same day. Also on that day, Charles A. Henry was made Company G’s second lieutenant, and John J. Goebel was commissioned as G Company’s first lieutenant. The remainder of Company G — ninety-five men — also enrolled and mustered in that same day; by the next month, the roster numbered ninety-eight — a figure that would hold until 1862. By the time the Civil War ended in 1865, a total of one hundred and ninety-five men would ultimately serve with G Company, including Thomas B. Leisenring, who would go on to become the company’s captain.

Military records at the time described Private Harrison Guth as a twenty-three-year-old shoemaker and resident of Lehigh County who was five feet, three inches tall with light hair, blue eyes and a fair complexion. He was known to family and friends as “Harry.”

The U.S. Capitol Building, unfinished at the time of President Abraham Lincoln’s inauguration, was still not completed when the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Washington, D.C. in September 1861 (public domain).

Following a brief light infantry training period at Camp Curtin, Private Harrison Guth and his company were sent by train with the 47th Pennsylvania to Washington, D.C., where they were stationed at “Camp Kalorama” on the Kalorama Heights near Georgetown, about two miles from the White House, beginning 21 September. Henry Wharton, a field musician (drummer) with the regiment’s C Company, penned an update the next day to his hometown newspaper, the Sunbury American:

After a tedious ride we have, at last, safely arrived at the City of ‘magnificent distances.’ We left Harrisburg on Friday last at 1 o’clock A.M. and reached this camp yesterday (Saturday) at 4 P.M., as tired and worn out a sett [sic] of mortals as can possibly exist. On arriving at Washington we were marched to the ‘Soldiers Retreat,’ a building purposely erected for the benefit of the soldier, where every comfort is extended to him and the wants of the ‘inner man’ supplied.

After partaking of refreshments we were ordered into line and marched, about three miles, to this camp. So tired were the men, that on marching out, some gave out, and had to leave the ranks, but J. Boulton Young, our ‘little Zouave,’ stood it bravely, and acted like a veteran. So small a drummer is scarcely seen in the army, and on the march through Washington he was twice the recipient of three cheers.

We were reviewed by Gen. McClellan yesterday [21 September 1861] without our knowing it. All along the march we noticed a considerable number of officers, both mounted and on foot; the horse of one of the officers was so beautiful that he was noticed by the whole regiment, in fact, so wrapt [sic] up were they in the horse, the rider wasn’t noticed, and the boys were considerably mortified this morning on dis-covering they had missed the sight of, and the neglect of not saluting the soldier next in command to Gen. Scott.

Col. Good, who has command of our regiment, is an excellent man and a splendid soldier. He is a man of very few words, and is continually attending to his duties and the wants of the Regiment.

…. Our Regiment will now be put to hard work; such as drilling and the usual business of camp life, and the boys expect and hope for an occasional ‘pop’ at the enemy.

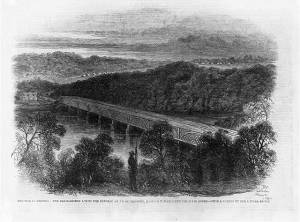

Chain Bridge across the Potomac above Georgetown looking toward Virginia, 1861 (The Illustrated London News, public domain).

On 24 September 1861, the members of Company G and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers officially mustered in with the U.S. Army. Three days later, on 27 September, a rainy, drill-free day which permitted many of the men to read or write letters home, the 47th Pennsylvanians were assigned to the 3rd Brigade of Brigadier-General Isaac Ingalls Stevens. By that afternoon, they were on the move again, headed for the Potomac River’s eastern side where, upon arriving at Camp Lyon in Maryland, they were ordered to march double-quick over a chain bridge and off toward Falls Church, Virginia.

Arriving at Camp Advance at dusk, the men pitched their tents in a deep ravine about two miles from the bridge they had just crossed, near a new federal military facility under construction (Fort Ethan Allen), which was also located near the headquarters of Brigadier-General William Farrar Smith (nicknamed “Baldy”), the commander of the Union’s massive Army of the Potomac (“Mr. Lincoln’s Army”). Armed with Mississippi rifles supplied by the Keystone State, their job was to help defend the nation’s capital.

Once again, Company C Musician Henry Wharton recapped the regiment’s activities, noting, via his 29 September letter home to the Sunbury American, that the 47th had changed camps three times in three days:

On Friday last we left Camp Kalorama, and the same night encamped about one mile from the Chain Bridge on the opposite side of the Potomac from Washington. The next morning, Saturday, we were ordered to this Camp [Camp Advance near Fort Ethan Allen, Virginia], one and a half miles from the one we occupied the night previous. I should have mentioned that we halted on a high hill (on our march here) at the Chain Bridge, called Camp Lyon, but were immediately ordered on this side of the river. On the route from Kalorama we were for two hours exposed to the hardest rain I ever experienced. Whew, it was a whopper; but the fellows stood it well – not a murmur – and they waited in their wet clothes until nine o’clock at night for their supper. Our Camp adjoins that of the N.Y. 79th (Highlanders.)….

We had not been in this Camp more than six hours before our boys were supplied with twenty rounds of ball and cartridge, and ordered to march and meet the enemy; they were out all night and got back to Camp at nine o’clock this morning, without having a fight. They are now in their tents taking a snooze preparatory to another march this morning…. I don’t know how long the boys will be gone, but the orders are to cook two days’ rations and take it with them in their haversacks….

There was a nice little affair came off at Lavensville [sic, Lewinsville], a few miles from here on Wednesday last; our troops surprised a party of rebels (much larger than our own.) killing ten, took a Major prisoner, and captured a large number of horses, sheep and cattle, besides a large quantity of corn and potatoes, and about ninety six [sic] tons of hay. A very nice day’s work. The boys are well, in fact, there is no sickness of any consequence at all in our Regiment….

The Big Chestnut Tree, Camp Griffin, Langley, Virginia, 1861 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Sometime during this phase of duty, as part of the 3rd Brigade, the 47th Pennsylvanians were moved to a site they initially christened “Camp Big Chestnut” in reference to the large chestnut tree located nearby. The site would eventually become known to the Keystone Staters as “Camp Griffin,” and was located roughly ten miles from Washington, D.C. While en route, according to historian Lewis Schmidt, “Pvt. Reuben Wetzel, a forty-six-year-old cook in Capt. Mickley’s Company G,” climbed up on a horse that was pulling his company’s wagon while his regiment was engaged in a march from Fort Ethan Allen to Camp Griffin (both in Virginia). When the regiment arrived at a deep ditch, “the horses lost their footing and the wagon overturned and plunged into the ditch, with ‘the old man, wagon, and horses, under everything.’”

Pageantry and Hard Work

On 11 October 1861, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers engaged in a grand review of Union Army troops at Bailey’s Cross Roads. In a letter that was written to family back home around this same time, Captain John Peter Shindel Gobin (the leader of C Company who would be promoted in 1864 to head the entire 47th Regiment) reported that companies D, A, C, F and I (the 47th Pennsylvania’s right wing) were ordered to picket duty after the left-wing companies (B, G, K, E, and H) had been forced to return to camp by Confederate troops. In his letter of 13 October, Henry Wharton described their duties, as well as their new home:

The location of our camp is fine and the scenery would be splendid if the view was not obstructed by heavy thickets of pine and innumerable chesnut [sic] trees. The country around us is excellent for the Rebel scouts to display their bravery; that is, to lurk in the dense woods and pick off one of our unsuspecting pickets. Last night, however, they (the Rebels) calculated wide of their mark; some of the New York 33d boys were out on picket; some fourteen or fifteen shots were exchanged, when our side succeeded in bringing to the dust, (or rather mud,) an officer and two privates of the enemy’s mounted pickets. The officer was shot by a Lieutenant in Company H [?], of the 33d.

Our own boys have seen hard service since we have been on the ‘sacred soil.’ One day and night on picket, next day working on entrenchments at the Fort, (Ethan Allen.) another on guard, next on march and so on continually, but the hardest was on picket from last Thursday morning ‘till Saturday morning – all the time four miles from camp, and both of the nights the rain poured in torrents, so much so that their clothes were completely saturated with the rain. They stood it nobly – not one complaining; but from the size of their haversacks on their return, it is no wonder that they were satisfied and are so eager to go again tomorrow. I heard one of them say ‘there was such nice cabbage, sweet and Irish potatoes, turnips, &c., out where their duty called them, and then there was a likelihood of a Rebel sheep or young porker advancing over our lines and then he could take them as ‘contraband’ and have them for his own use.’ When they were out they saw about a dozen of the Rebel cavalry and would have had a bout with them, had it not been for…unlucky circumstance – one of the men caught the hammer of his rifle in the strap of his knapsack and caused his gun to fire; the Rebels heard the report and scampered in quick time….

On Friday morning, 22 October, the 47th engaged in a divisional review, described by historian Lewis Schmidt as massing “about 10,000 infantry, 1000 cavalry, and twenty pieces of artillery all in one big open field.” In late October, according to Schmidt, the men from Companies B, G and H woke at 3 a.m., assembled a day’s worth of rations, marched four miles from camp, and took over picket duties from the 49th New York:

Company B was stationed in the vicinity of a Mrs. Jackson’s house, with Capt. Kacy’s Company H on guard around the house. The men of Company B had erected a hut made of fence rails gathered around an oak tree, in front of which was the house and property, including a persimmon tree whose fruit supplied them with a snack. Behind the house was the woods were the Rebels had been fired on last Wednesday morning while they were chopping wood there.

In his letter of 17 November, Henry Wharton revealed still more details about life at Camp Griffin:

This morning our brigade was out for inspection; arms, accoutrements [sic], clothing, knapsacks, etc, all were out through a thorough examination, and if I must say it myself, our company stood best, A No. 1, for cleanliness. We have a new commander to our Brigade, Brigadier General Brannen [sic], of the U.S. Army, and if looks are any criterion, I think he is a strict disciplinarian and one who will be as able to get his men out of danger as he is willing to lead them to battle….

The boys have plenty of work to do, such as piquet [sic] duty, standing guard, wood-chopping, police duty and day drill; but then they have the most substantial food; our rations consist of fresh beef (three times a week) pickled pork, pickled beef, smoked pork, fresh bread, daily, which is baked by our own bakers, the Quartermaster having procured portable ovens for that purpose, potatoes, split peas, beans, occasionally molasses and plenty of good coffee, so you see Uncle Sam supplies us plentifully….

A few nights ago our Company was out on piquet [sic]; it was a terrible night, raining very hard the whole night, and what made it worse, the boys had to stand well to their work and dare not leave to look for shelter. Some of them consider they are well paid for their exposure, as they captured two ancient muskets belonging to Secessia. One of them is of English manufacture, and the other has the Virginia militia mark on it. They are both in a dilapidated condition, but the boys hold them in high estimation as they are trophies from the enemy, and besides they were taken from the house of Mrs. Stewart, sister to the rebel Jackson who assassinated the lamented Ellsworth at Alexandria. The honorable lady, Mrs. Stewart, is now a prisoner at Washington and her house is the headquarters of the command of the piquets [sic]….

Since the success of the secret expedition, we have all kinds of rumors in camp. One is that our Brigade will be sent to the relief of Gen. Sherman, in South Carolina. The boys all desire it and the news in the ‘Press’ is correct, that a large force is to be sent there, I think their wish will be gratified….

On 21 November, the 47th participated in a morning divisional headquarters review that was overseen by Colonel Tilghman Good, followed by brigade and division drills all afternoon. According to Schmidt, “each man was supplied with ten blank cartridges.” Afterward, “Gen. Smith requested Gen. Brannan to inform Col. Good that the 47th was the best regiment in the whole division.”

As a reward — and in preparation for bigger things to come, Brigadier-General John Milton Brannan obtained brand new Springfield rifles for every member of the 47th Pennsylvania.

1862

The City of Richmond, a sidewheel steamer, transported Union troops during the Civil War (Maine, circa late 1860s, public domain).

Ordered by senior Union Army leaders to head for Maryland, Private Harrison Guth and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers departed from Camp Griffin at 8:30 a.m. on Wednesday, 22 January 1862. Marching through deep mud with their equipment for three miles in order to reach the railroad station at Falls Church, they were then transported by rail to Alexandria, Virginia, where they boarded the steamship City of Richmond. Transported via the Potomac River to the Washington Arsenal, they were reequipped before they were marched off for dinner and rest at the Soldiers’ Retreat in Washington, D.C.

The next afternoon, they hopped aboard cars on the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad, and headed for Annapolis, Maryland. Arriving around 10 p.m., they were assigned quarters in barracks at the United States Naval Academy. They then spent that Friday through Monday (24-27 January 1862) loading their equipment and other supplies onto the steamship Oriental.

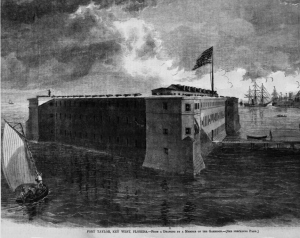

Ferried to the Oriental by smaller steamers during the afternoon of 27 January 1862, the enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry commenced boarding the big steamship, followed by their officers. Then, per the directive of Brigadier-General Brannan, the Oriental steamed away for the Deep South at 4 p.m. and headed for Florida which, despite its secession from the Union, remained strategically important to the Union due to the presence of Forts Taylor and Jefferson in Key West and the Dry Tortugas.

Lighthouse, Key West, Florida, early to mid-1800s (Florida for Tourists, Invalids, and Settlers, George M. Barbour, 1881, public domain).

In early February 1862, Private Harrison Guth and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers arrived in Key West, Florida, where they were assigned to garrison Fort Taylor. During the weekend of Friday, 14 February, the regiment introduced itself to Key West residents as it paraded through the streets of the city. That Sunday, a number of the men from the regiment mingled with local residents at area church services.

Drilling daily in heavy artillery tactics and other military strategies, they felled trees, built new roads and helped to strengthen the facility’s fortifications. But there were lighter moments as well.

According to a letter penned by Henry Wharton on 27 February 1862, the regiment commemorated the birthday of former U.S. President George Washington with a parade, a special ceremony involving the reading of Washington’s farewell address to the nation (first delivered in 1796), the firing of cannon at the fort, and a sack race and other games on 22 February. The festivities resumed two days later when the 47th Pennsylvania’s Regimental Band hosted an officers’ ball at which “all parties enjoyed themselves, for three o’clock of the morning sounded on their ears before any motion was made to move homewards.” This was then followed by a concert by the Regimental Band on Wednesday evening, 26 February.

As the 47th Pennsylvanians soldiered on, many were realizing that they were operating in an environment that was far more challenging than what they had experienced to date — and in an area where the water quality was frequently poor. That meant that disease would now be their constant companion — an unseen foe that would continue to claim the lives of multiple members of the regiment during this phase of duty — if they weren’t careful.

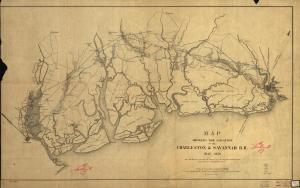

This 1856 map of the Charleston & Savannah Railroad shows the island of Hilton Head, South Carolina in relation to the towns of Beaufort and Pocotaligo (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Next ordered to Hilton Head, South Carolina from mid-June through July, the 47th Pennsylvanians camped near Fort Walker before relocating to the Beaufort District, Department of the South, roughly thirty-five miles away. Frequently assigned to hazardous picket detail north of their main camp, which put them at increased risk from enemy sniper fire, the members of the 47th Pennsylvania became known for their “attention to duty, discipline and soldierly bearing,” and “received the highest commendation from Generals Hunter and Brannan,” according to historian Samuel P. Bates.

Detachments from the regiment were also assigned to the Expedition to Fenwick Island (9 July) and the Demonstration against Pocotaligo (10 July), while men from Companies B and H “crossed the Coosaw River at the Port Royal Ferry and drove off the Rebel pickets before returning ‘home’ without a loss,” according to Schmidt. The actions were the Union’s response to the burning by Confederate troops of the ferry house at Port Royal.

Saint John’s Bluff and the Capture of a Confederate Steamer

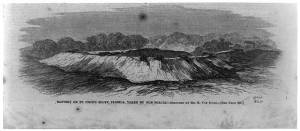

Earthworks surrounding the Confederate battery atop Saint John’s Bluff along the Saint John’s River in Florida (J. H. Schell, 1862, public domain).

During a return expedition to Florida beginning 30 September, Private Harrison Guth and his fellow 47th Pennsylvanians joined with the 1st Connecticut Battery, 7th Connecticut Infantry, and part of the 1st Massachusetts Cavalry in assaulting Confederate forces at their heavily protected camp at Saint John’s Bluff, overlooking the Saint John’s River area. Trekking and skirmishing through roughly twenty-five miles of dense swampland and forests after disembarking from ships at Mayport Mills on 1 October, they subsequently captured artillery and ammunition stores (on 3 October) that had been abandoned by Confederate forces during a bombardment of the bluff by Union gunboats.

According to Henry Wharton, “On the day following our occupation of these works the guns were dismounted and removed on board the steamer Neptune, together with the shot and shell, and removed to Hilton Head. The powder was all used in destroying the batteries.”

Meanwhile that same weekend (Friday and Saturday, 3-4 October 1862), Brigadier-General Brannan, who was quartered on board the Ben Deford as the Union expedition’s commanding officer, was busy penning reports to his superiors while also planning the next move of his expeditionary force. That Saturday, Brannan chose several officers to direct their subordinates to prepare rations and ammunition for a new foray that would take them roughly twenty miles upriver to Jacksonville. (A sophisticated hub of cultural and commercial activities with a racially diverse population of more than two thousand residents, the city had repeatedly changed hands between the Union and Confederacy until its occupation by Union forces on 12 March 1862.) Among the Union soldiers selected for this mission were 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers from Company C, Company E and Company K.

Boarding the Union gunboat Darlington (formerly a Confederate steamer), they moved upriver, along the Saint John’s, with protection from the Union gunboat Hale, ultimately traveling a distance of two hundred miles. Charged with locating and capturing Confederate ships that had been engaged in furnishing troops, ammunition and other supplies to Confederate Army units scattered throughout the region, including the batteries at Saint John’s Bluff and Yellow Bluff, they played a key role in capturing the Governor Milton, a Confederate steamer that was docked near Hawkinsville.

Integration of the Regiment

The 47th Pennsylvania also made history during the month of October 1862 as it became an integrated regiment, adding to its muster rolls several Black men who had escaped chattel enslavement from plantations near Beaufort, South Carolina. Among the formerly enslaved men who enlisted at this time were Bristor Gethers, Abraham Jassum and Edward Jassum.

Battle of Pocotaligo, South Carolina

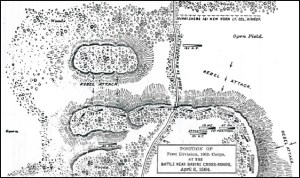

Highlighted version of the U.S. Army map of the Coosawhatchie-Pocotaligo Expedition, 22 October 1862 (public domain).

From 21-23 October 1862, under the brigade and regimental commands of Colonel Tilghman Good and Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers joined with other Union troops in engaging heavily protected Confederate forces in and around Pocotaligo, South Carolina, including at the Frampton Plantation and the Pocotaligo Bridge, a key piece of railroad infrastructure that senior Union military leaders felt should be eliminated.

Harried by snipers while en route to destroy the bridge, they also met resistance from Confederate artillerymen who opened fire as they entered an open cotton field.

Those headed toward higher ground at the Frampton Plantation fared no better as they encountered rifle and cannon fire from the surrounding forests. But the Union soldiers would not give in. Grappling with Rebel troops wherever they found them, they pursued them for four miles as the Confederate Army retreated to the bridge. Once there, the 47th Pennsylvania relieved the 7th Connecticut.

The engagement proved to be a costly one for the 47th Pennsylvania, however, with multiple members of the regiment killed instantly or so grievously wounded that they died the next day or within weeks of the battle. Among those killed in action was Captain Charles Mickley of Company G; one of the mortally wounded was K Company Captain George Junker.

Also wounded in action that day was Private William Hensler of Company G. Treated for a head wound by by regimental surgeons in the field and then back at the Union Army’s general hospital in Hilton Head, he became one of the incredibly fortunate members of the 47th Pennsylvania to survive, and was subsequently able to return to duty.

* Note: While Private Harrison Guth was battling Confederate troops in South Carolina, Daniel H. Gackenbach (the North Whitehall tenant farmer who had employed him as a servant in 1860) was back home in Pennsylvania enlisting for military service. Following his enrollment on 22 October 1862, Daniel Gackenbach was officially mustered in as a musician with Company H of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry on 29 October and was then transported to America’s Deep South. After connecting with his regiment, he was reassigned to the 47th Pennsylvania’s second Regimental Band as an Eb tuba player (E-flat tuba).

Ordered back to Key West on 15 November 1862, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers would spend the coming year guarding federal installations in Florida. Companies A, B, C, E, G, and I would once again garrison Fort Taylor in Key West, along with the Regimental Band, while the men from Companies D, F, H, and K would garrison Fort Jefferson, the Union’s remote outpost in the Dry Tortugas off the southern coast of Florida.

After packing their belongings at their Beaufort, South Carolina encampment and loading their equipment onto the U.S. Steamer Cosmopolitan, the officers and enlisted members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry sailed toward the mouth of the Broad River on 15 December 1862, and anchored briefly at Port Royal Harbor in order to allow the regiment’s medical director, Elisha W. Baily, M.D., and members of the regiment who had recuperated enough from their Pocotaligo-related battle injuries at the Union’s general hospital at Hilton Head, to rejoin the regiment.

At 5 p.m. that same evening, the regiment sailed for Florida, during what was described by several members of the 47th as a treacherous and nerve-wracking voyage. According to historian Lewis Schmidt, the ship’s captain “steered a course along the coast of Florida for most of the voyage,” which made the voyage more precarious “because of all the reefs.” On 16 December, “the second night, the ship was jarred as it ran aground on one during a storm, but broke free, and finally steered a course further from shore, out in the Gulf Stream.”

In a letter penned to the Sunbury American on 21 December, Company C soldier Henry Wharton provided the following details about the regiment’s trip:

On the passage down, we ran along almost the whole coast of Florida. Rather all dangerous ground, and the reefs are no playthings. We were jarred considerably by running on one, and not liking the sensation our course was altered for the Gulf Stream. We had heavy sea all the time. I had often heard of ‘waves as big as a house,’ and thought it was a sailors yarn, but I have seen ’em and am perfectly satisfied; so now, not having a nautical turn of mind, I prefer our movements being done on terra firma, and leave old neptune to those who have more desire for his better acquaintance. A nearer chance of a shipwreck never took place than ours, and it was only through Providence that we were saved. The Cosmopolitan is a good riverboat, but to send her to sea, loadened [sic, loaded] with U.S. troops is a shame, and looks as though those in authority wish to get clear of soldiers in another way than that of battle. There was some sea sickness on our passage; several of the boys ‘casting up their accounts’ on the wrong side of the ledger.

According to Corporal George Nichols of Company E, “When we got to Key West the Steamer had Six foot of water in her hole [sic, hold]. Waves Mountain High and nothing but an old river Steamer. With Eleven hundred Men on I looked for her to go to the Bottom Every Minute.”

Although the Cosmopolitan arrived at Key West Harbor on Thursday, 18 December, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers did not set foot on Florida soil until noon the next day. The men from Companies C and I were immediately marched to Fort Taylor, while the men from Companies B and E were assigned to older barracks that had previously been erected by the U.S. Army. Members of Companies A and G were marched to the newer “Lighthouse Barracks” located on “Lighthouse Key.”

1863

Stationed in Florida for the entire year of 1863, Private Harrison Guth was promoted to the rank of corporal on 17 February 1863. Ordered to “hold the fort,” he and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were primarily responsible for preventing foreign powers from assisting the Confederate Army and Navy in gaining control over federal installations and other territories across the Deep South. In addition, the regiment was also called upon to play an ongoing role in weakening Florida’s ability to supply and transport food and troops throughout areas held by the Confederate States of America.

Prior to intervention by the Union Army and Navy, the owners of plantations, livestock ranches and fisheries, as well as the operators of smaller family farms across Florida, had been able to consistently furnish beef and pork, fish, fruits, and vegetables to Confederate troops stationed throughout the Deep South during the first year of the American Civil War. Large herds of cattle were raised near Fort Myers, for example, while orchard owners in the Saint John’s River area were actively engaged in cultivating sizeable orange groves. (Other types of citrus trees were found growing throughout more rural areas of the state.)

Florida was also a major producer of salt, which was used as a preservative for food. Consequently, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers and other Union troops across Florida were ordered to capture or destroy salt manufacturing plants in order to further curtail the enemy’s access to food.

But once again, they were performing their duties in often dangerous conditions. The weather was frequently hot and humid as spring turned to summer, mosquitos and other insects were an ever-present annoyance (and a serious threat when they were carrying tropical diseases), and there were also scorpions and snakes that put the health of Corporal Guth and his comrades at further risk. In addition, there was a serious shortage of clean water for drinking and bathing.

Fort Jefferson and its wharf areas, Dry Tortugas, Florida (Harper’s Weekly, 23 February 1861, public domain).

Despite those hardships, when given the opportunity to leave military service when their initial terms of enlistment expired, the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers chose to re-enlist and continue their fight to save the Union. Among those who re-enlisted that year was Corporal Harrison Guth, who was re-enrolled with Company G of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry at Fort Jefferson in Florida’s Dry Tortugas on 20 October 1863 — giving him the coveted designation of “Veteran Volunteer,” per General Orders, No. 191.

* Note: Shortly before Christmas that year, another new recruit from Lehigh County joined the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry. His name warrants a mention here because he would ultimately develop an important bond with Corporal Harrison Guth. That nineteen-year-old recruit’s name was Griffin Reinert, and he was a brother of Martha Reinert (the woman Corporal Guth would later marry). Known to family and friends as “Griff,” he officially mustered in for duty as a private with Company F of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers on 21 December 1863.

1864

In early January 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers experienced yet another significant change when members of the regiment were ordered to expand the Union’s reach by sending part of the regiment north to retake Fort Myers, a federal installation that had been abandoned in 1858, following the federal government’s third war with the Seminole Indians. In response, Company A Captain Richard Graeffe and a detachment of his subordinates traveled north, captured the fort and began conducting cattle raids to provide food for the growing Union troop presence across the region. They subsequently turned their fort not only into their base of operations, but into a shelter for pro-Union supporters, escaped slaves, Confederate deserters, and others fleeing Rebel troops.

Red River Campaign

Meanwhile, all of the other companies of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry had begun preparing for the regiment’s history-making journey to Louisiana. Boarding yet another steamer, the Charles Thomas, the men from Companies B, C, D, I, and K headed for Algiers, Louisiana (across the river from New Orleans), followed on 1 March by the men from Companies E, F, G, and H.

Upon the second group’s arrival, the now almost-fully-reunited-regiment moved by train to Brashear City (now Morgan City), before heading to Franklin by steamer through the Bayou Teche. There, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry joined the 2nd Brigade, 1st Division of the 19th Corps (XIX) of the United States’ Army of the Gulf, and became the only regiment from the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania to serve in the Red River Campaign commanded by Union Major-General Nathaniel P. Banks. (Unable to reach Louisiana until 23 March, the soldiers from Company A were assigned to detached duty while awaiting transport that enabled them to reconnect with their regiment at Alexandria, Louisiana on 9 April.)

Map of key 1864 Red River Campaign locations, showing the battle sites of Sabine Cross Roads, Pleasant Hill and Mansura in relation to the Union’s occupation sites at Alexandria, Grand Ecore, Morganza, and New Orleans (excerpt from Dickinson College/U.S. Library of Congress map, public domain).

The early days on the ground quickly woke Corporal Harrison Guth and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers up to just how grueling their new phase of duty would be. From 14-26 March, most members of the 47th marched for Alexandria and Natchitoches, near the top of the L-shaped state. Among the towns that the 47th Pennsylvanians passed through were New Iberia, Vermilionville (now part of Lafayette), Opelousas, and Washington.

From 4-5 April 1864, the regiment added to its roster of young Black soldiers when Aaron Bullard (later known as Aaron French), James Bullard, John Bullard, Samuel Jones, and Hamilton Blanchard (also known as John Hamilton) enrolled for military service with the 47th Pennsylvania at Natchitoches. According to their respective entries in the Civil War Veterans’ Card File at the Pennsylvania State Archives and on regimental muster rolls, the men were officially mustered into the regiment on 22 June at Morganza, Louisiana. Several of their entries noted that they were assigned the rank of “Colored Cook” while others were given the rank of “Under-Cook.”

Often short on food and water throughout their long, harsh-climate trek, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers encamped briefly at Pleasant Hill (now the Village of Pleasant Hill) the night of 7 April, before continuing on the next day.

Rushed into battle ahead of other regiments in the second division, sixty members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry were cut down on 8 April 1864 during the intense volley of fire in the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads (also known as the Battle of Mansfield due to its proximity to the town of Mansfield). The fighting waned only when darkness fell. The exhausted, but uninjured collapsed beside the gravely wounded and dead. After midnight, the surviving Union troops withdrew to Pleasant Hill.

* Note: Among the wounded who received prompt medical attention at the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental hospital at Pleasant Hill, after the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads, was F Company Private Griff Reinert, the future brother-in-law of G Company Corporal Harrison Guth. Fortunately, despite having sustained a gunshot wound to his lower jaw, Private Reinert survived and, after a long period of treatment and recovery, was able to return home to his loved ones.

The next day, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were ordered into a critically important defensive position at the far right of the Union lines, their right flank spreading up unto a high bluff. By 3 p.m., after enduring a midday charge by the troops of Confederate Major-General Richard Taylor (a plantation owner who was the son of Zachary Taylor, a former president of the United States), the brutal fighting still showed no signs of ending. Suddenly, just as the 47th was shifting to the left side of the Union force, the men of the 47th were forced to bolster the 165th New York’s buckling lines by blocking another Confederate assault.

During that engagement (now known as the Battle of Pleasant Hill), the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers succeeded in recapturing a Massachusetts artillery battery that had been lost during the earlier Confederate assault. Unfortunately, the regiment’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Warren Alexander, and its two color-bearers, Sergeants Benjamin Walls and William Pyers, were wounded. Alexander sustained wounds to both of his legs, and Walls was shot in the left shoulder as he attempted to mount the 47th Pennsylvania’s colors on caissons that had been recaptured, while Pyers was wounded as he grabbed the flag from Walls to prevent it from falling into Confederate hands.

All three survived the day, however, and continued to serve with the regiment, but many others, like K Company Sergeant Alfred Swoyer, were killed in action during those two days of chaotic fighting, or were wounded so severely that they were unable to continue the fight. (Swoyer’s final words were, “They’re coming nine deep!” Shot in the right temple shortly afterward, his body was never recovered).

Still others were captured by Confederate troops, marched roughly one hundred and twenty-five miles to Camp Ford, a Confederate Army prison camp near Tyler, Texas, and held there as prisoners of war until they were released during a series of prisoner exchanges that began on 22 July and continued through November. At least two members of the regiment never made it out of that prison camp alive; another died at a Confederate hospital in Shreveport.

Meanwhile, as the captured 47th Pennsylvanians were being spirited away to Camp Ford, the bulk of the regiment was carrying out orders from senior Union Army leaders to head for Grand Ecore, Louisiana. Encamped there from 11-22 April, the Union soldiers engaged in the hard labor of strengthening regimental and brigade fortifications.

They then moved back to Natchitoches Parish on 22 April. While they were in route, they were attacked again, this time, at the rear of their retreating brigade, but they were able to end the encounter quickly and move on to reach Cloutierville at 10 p.m. that same night (after a forty-five-mile march).

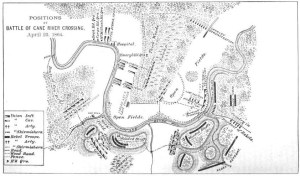

The 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were stationed just to the left of the “Thick Woods” with Emory’s 2nd Brigade, 1st Division as shown on this map of Union troop positions for the Battle of Cane River Crossing at Monett’s Ferry, Louisiana, 23 April 1864 (Major-General Nathaniel Banks’ official Red River Campaign Report, public domain).

The next morning (23 April), episodic skirmishing quickly roared into the flames of a robust fight. As part of the advance party led by Union Brigadier-General William Emory, the 47th Pennsylvanians took on the Confederate Cavalry of Brigadier-General Hamilton Bee in the Battle of Cane River (also known as “the affair at Monett’s Ferry” or the “Cane River Crossing”).

Responding to a barrage from the Confederate Artillery’s twenty-pound Parrott guns and from enemy troops positioned atop a bluff and near a bayou, Brigadier-General Emory directed one of his brigades to keep Bee’s Confederate troops busy while sending two other brigades to find a safe spot for the Union’s forces to cross the Cane River. As part of “the beekeepers,” the 47th Pennsylvania supported Smith’s artillery.

Meanwhile, additional troops under Smith’s command attacked Bee’s flank to force a Rebel retreat, and then erected a series of pontoon bridges that enabled the 47th Pennsylvania and other Union regiments to make the Cane River Crossing by the next day. As the Confederates retreated, they torched their own food stores, as well as the cotton supplies of their fellow southerners. In a letter penned from Morganza, C Company Musician Henry Wharton described what had happened:

Our sojourn at Grand Score was for eleven days, during which time our position was well fortified by entrenchments for a length of five miles, made of heavy logs, five feet high and six feet wide, filled in with dirt. In front of this, trees were felled for a distance of two hundred yards, so that if the enemy attacked we had an open space before us which would enable our forces to repel them and follow if necessary. But our labor seemed to the men as useless, for on the morning of 22d April, the army abandoned these works and started for Alexandria. From our scouts it was ascertained that the enemy had passed some miles to our left with the intention of making a stand against our right at Bayou Cane, where there is a high bluff and dense woods, and at the same attack Smith’s forces who were bringing up the rear. This first day was a hard one for the boys, for at 10 o’clock at night they made Cloutierville, a distance of forty drive miles. On that day our rear was attacked which caused our forces to reverse their front and form in line of battle, expecting too, to go back to the relief of Smith, but he needed no assistance, sending word to the front that he had ‘whipped them, and could do it again.’ It was well that Banks made so long a march on that day, for on the next we found the enemy prepared to carry out their design of attacking us front and rear. Skirmishing commenced early in the morning and as our columns advanced he fell back towards the bayou, when we soon discovered the position of their batteries on the bluff. There was then an artillery duel by the smaller pieces, and some sharp fighting by the cavalry, when the ‘mule battery,’ twenty pound Parrott guns opened a heavy fire, which soon dislodged them, forcing the chivalry to flee in a manner not at all suitable to their boasted courage. Before this one cavalry, the 3d Brigade of the 1st Div., and Birges’ brigade of the second, had crossed the bayou and were doing good service, which, with the other work, made the enemy show their heels. The 3d brigade done some daring deeds in this fight, as also did the cavalry. In one instance the 3d charged up a hill almost perpendicular, driving the enemy back by the bayonet without firing a gun. The woods on this bluff was so thick that the cavalry had to dismount and fight on foot. During the whole of the day, our brigade, the 2d, was supporting artillery, under fire all the time, and could not give Mr. Reb a return shot.

While we were fighting in front, Smith was engaged some miles in the rear, but he done his part well and drove them back. The rebel commanders thought by attacking us in the rear, and having a large face on the bluffs, they would be able to capture our train and take us all prisoners, but in this they were mistaken, for our march was so rapid that we were on them before they had thrown up the necessary earthworks. Besides they underrated the amount of our artillery, calculating from the number engaged at Pleasant Hill. The rebels say it ‘seems as though the Yankees manufacture, on short notice, artillery to order, and the men are furnished with wings when they wish to make a certain point.’

The damage done to the Confederate cause by the burning of cotton was immense. On the night of the 22d our route was lighted up for miles and millions of dollars worth if this production was destroyed. This loss will be felt more by Davis & Co., than several defeats in this region, for the basis of the loan in England was on the cotton in Louisiana.

After the rebels had fled from the bluff the negro troops put down the pontoons, and by ten that night we were six miles beyond the bayou safely encamped. The next morning we moved forward and in two days were in Alexandria. Johnnys followed Smith’s forces, keeping out of range of his guns, except when he had gained the eminence across the bayou, when he punished them (the rebs) severely.

Sketches of the crib and tree dams designed by Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey to improve the water levels of the Red River near Alexandria, Louisiana, spring 1864 (Joseph Bailey, “Report on the Construction of the Dam Across the Red River,” 1865, public domain).

Having finally reached Alexandria on 26 April, they learned that they would remain at their latest new camp for at least two weeks. Placed temporarily under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Joseph Bailey, they were assigned yet again to the hard labor of construction work, helping to erect “Bailey’s Dam,” a timber structure that was designed to enable Union gun boats to safely navigate the fluctuating water levels of the Red River. According to Musician Henry Wharton:

We were at Alexandria seventeen days, during which time the men were kept busy at throwing up earthworks, foraging and three times went out some distance to meet the enemy, but they did not make their appearance in numbers large enough for an engagement. The water in the Red river had fallen so much that it prevented the gun boats from operating with us, and kept our transports from supplying the troops with rations, (and you know soldiers, like other people will eat), so Banks was compelled to relinquish his designs on Shreveport and fall back to the Mississippi. To do this a large dam had to be built on the falls at Alexandria to get the iron clads down the river. After a great deal of labor this was accomplished and by the morning of May 13th the last one was through the shute [sic, chute], when we bade adieu to Alexandria, marching through the town with banners flying and keeping step to the music of ‘Rally around the flag,’ and ‘When this cruel war is over.’ The next morning, at our camping place, the fleet of boats passed us, when we were informed that Alexandria had been destroyed by fire – the act of a dissatisfied citizen and several negroes. Incendiary acts were strictly forbidden in a general order before we left the place, and a cavalry guard was left in the rear to see the order enforced. After marching a few miles skirmishing commenced in front between the cavalry and the enemy in riflepits on the bank of the river, but they were easily driven away. When we came up we discovered their pits and places where there had been batteries planted. At this point the John Warren, an unarmed transport, on which were sick soldiers and women, was fired into and sunk, killing many and those that were not drowned taken prisoners. A tin-clad gunboat was destroyed at the same place, by which we lost a large mail. Many letters and directed envelopes were found on the bank – thrown there after the contents had been read by the unprincipled scoundrels. The inhumanity of Guerrilla bands in this department is beyond belief, and if one did not know the truth of it or saw some of their barbarities, he would write it down as the story of a ‘reliable gentleman’ or as told by an ‘intelligent contraband.’ Not satisfied with his murderous intent on unarmed transports he fires into the Hospital steamer Laurel Hill, with four hundred sick on board. This boat had the usual hospital signal floating fore and aft, yet, notwithstanding all this, and the customs of war, they fired on them, proving by this act that they are more hardened than the Indians on the frontier.

Continuing their march, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers headed toward Avoyelles Parish. According to Wharton:

On Sunday, May 15th, we left the river road and took a short route through the woods, saving considerable distance. The windings of the Red river are so numerous that it resembles the tape-worm railroad where with the politicians frightened the dear people during the administration of Ritner and Stevens. — We stopped several hours in the woods to leave cavalry pass, when we moved forward and by four o’clock emerged into a large open plain where we formed into line of battle, expecting a regular engagement. The enemy, however, retired, and we advanced ’till dark, when the forces halted for the night with orders to rest on their arms. ‘Twas here that Banks rode through our regiment, amidst the cheers of the boys, and gave the pleasant news that Grant had defeated Lee.

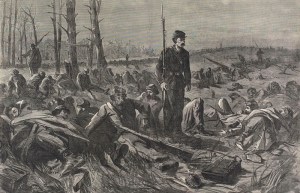

“Sleeping on Their Arms” by Winslow Homer (Harper’s Weekly, 21 May 1864).

“Resting on their arms” (half-dozing, without pitching their tents, and with their rifles right beside them), they were now positioned just outside of Marksville, on the eve of the 16 May 1864 Battle of Mansura, which unfolded as follows, according to Wharton:

Early next morning we marched through Marksville into a prairie nine miles long and six wide where every preparation was made for a fight. The whole of our force was formed in line, in support of artillery in front, who commenced operations on the enemy driving him gradually from the prairie into the woods. As the enemy retreated before the heavy fire of our artillery, they reached Missoula [sic, Mansura], where they formed in column, taking the whole field in an attempt to flank the enemy, but their running qualities were so good that we were foiled. The maneuvring [sic, maneuvering] of the troops was handsomely done, and the movements was [sic, were] one of the finest things of the war. The fight of artillery was a steady one of five miles. The enemy merely stood that they might cover the retreat of their infantry and train under cover of their artillery. Our loss was slight. Of the rebels we could not ascertain directly, but learned from citizens who had secreted themselves during the fight, that they had many killed and wounded, who threw them into wagons, promiscuously, and drove them off so that we could not learn their casualties. The next day we moved to Simmsport [sic, Simmesport] on the Achafalaya [sic, Atchafalaya] river, where a bridge was made by putting the transports side by side, which enabled the troops and train to pass safely over.– The day before we crossed the rebels attacked Smith, thinking it was but the rear guard, in which they, the graybacks, were awfully cut up, and four hundred prisoners fell into our hands. Our loss in killed and wounded was ninety. This fight was the last one of the expedition. The whole of the force is safe on the Mississippi, gunboats, transports and trains. The 16th and 17th have gone to their old commands.

It is amusing to read the statements of correspondents to papers North, concerning our movements and the losses of the army. I have it from the best source that the Federal loss from Franklin to Mansfield, and from their [sic, there] to this point does not exceed thirty-five hundred in killed, wounded and missing, while that of the rebels is over eight thousand.

Union Army base at Morganza Bend, Louisiana, circa 1863-1865 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Continuing on, the healthy members of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry marched for Simmesport and then Morganza, where they made camp again. While encamped there, the nine formerly enslaved Black men who had enlisted with the regiment in Beaufort, South Carolina (1862) and Natchitoches, Louisiana (1864) were officially mustered into the regiment between 22-24 June.

The regiment then moved on and arrived in New Orleans in late June. On the Fourth of July, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers received orders to return to the East Coast. Three days later, they began loading the regiment and its men onto ships, a process that unfolded in two stages. Companies A, C, D, E, F, H, and I boarded the U.S. Steamer McClellan on 7 July and departed that day, while the members of Companies B, G and K, including Corporal Harrison Guth, remained behind, awaiting transport. They subsequently departed aboard the Blackstone, weighing anchor and sailing forth at the end of that month. Arriving in Virginia, on 28 July, the second group reconnected with the first group at Monocacy, having missed an encounter with President Abraham Lincoln and the Battle of Cool Spring at Snicker’s Gap in mid-July (a battle in which the first group of 47th Pennsylvanians had participated).

Sheridan’s 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign

General Crook’s Battle Near Berryville, Virginia, September 3, 1864 (James E. Taylor, public domain).

Attached to the Middle Military Division, U.S. Army of the Shenandoah, beginning in early August of 1864, and placed under the command of Union Major-General Philip H. Sheridan, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteer Infantry was assigned to defensive duties in and around Halltown, and also engaged over the next several weeks in a series of back-and-forth movements between Halltown, Berryville, Middletown, Charlestown, and Winchester as part of a “mimic war” being waged by Sheridan’s Union forces with those commanded by Confederate Lieutenant-General Jubal Early.

* Note: Sometime during this phase of duty, Musician Daniel H. Gackenbach (the North Whitehall tenant farmer who had employed Harrison Guth as a servant in 1860) fell ill. Hospitalized as his health continued to decline, Gackenbach was placed on the sick roll for the 47th Pennsylvania, where he remained for the duration of his term of enlistment. Per notations on regimental rosters, Musician Gackenbach was: “In Hosp. since 8-64. Supposed to be discharged.” (He would still be listed as absent due to illness on Christmas Day in 1865 when the regiment was officially mustered out for the final time.)

From 3-4 September 1864, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers re-engaged with Confederate forces in the Battle of Berryville. Two weeks later, multiple 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers opted to depart from the army by honorably mustering out upon expiration of their respective terms of service on 18 September.

Those members of the 47th who remained on duty, like Corporal Harrison Guth, were about to engage in their regiment’s greatest moments of valor.

Battles of Opequan and Fisher’s Hill, September 1864

Together with other regiments under the command of Union Major-General Philip H. (“Little Phil”) Sheridan and Brigadier-General William H. Emory, commander of the 19th Corps, the members of Company D and their fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers helped to inflict heavy casualties on Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate forces at Opequan (also spelled as “Opequon” and referred to as “Third Winchester”). The battle is still considered by many historians to be one of the most important during Sheridan’s 1864 campaign; the Union’s victory here helped to ensure the reelection of President Abraham Lincoln.

The 47th Pennsylvania’s march toward destiny at Opequan began at 2 a.m. on 19 September 1864 as the regiment left camp and joined up with others in the Union’s 19th Corps. After advancing slowly from Berryville toward Winchester, the 19th Corps became bogged down for several hours by the massive movement of Union troops and supply wagons, enabling Early’s men to dig in. After finally reaching the Opequan Creek, Sheridan’s men came face to face with the Confederate Army commanded by Early. The fighting, which began in earnest at noon, was long and brutal. The Union’s left flank (6th Corps) took a beating from Confederate artillery stationed on high ground.

Victory of Philip Sheridan’s Union Army over Jubal Early’s Confederate forces, Battle of Opequan, 19 September 1864 (Kurz & Allison, circa 1893, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

Meanwhile, the 47th Pennsylvania and the 19th Corps were directed by Brigadier-General William Emory to attack and pursue Major-General John B. Gordon’s Confederate forces. Some success was achieved, but casualties mounted as another Confederate artillery group opened fire on Union troops trying to cross a clearing. When a nearly fatal gap began to open between the 6th and 19th Corps, Sheridan sent in units led by Brigadier-Generals Emory Upton and David A. Russell. Russell, hit twice — once in the chest, was mortally wounded. The 47th Pennsylvania opened its lines long enough to enable the Union cavalry under William Woods Averell and the foot soldiers of General George Crook to charge the Confederates’ left flank.

Afterward, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were sent out on skirmishing parties before making camp at Cedar Creek. Moving forward, they would continue to distinguish themselves in battle, but would do so without two more of their respected commanders: Colonel Tilghman Good, founder of the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers; and Good’s second-in-command, Lieutenant-Colonel George Alexander, who mustered out from 23-24 September upon the expiration of their respective terms of service.

Fortunately, they were replaced by others equally admired both for their temperament and their front line experience: John Peter Shindel Gobin, Charles W. Abbott and Levi Stuber, who ultimately became the three most senior leaders of the regiment.

Battle of Cedar Creek, October 1864

Alfred Waud’s 1864 sketch, “Surprise at Cedar Creek,” captured the flanking attack on the rear of Union Brigadier-General William Emory’s 19th Corps by Lieutenant-General Jubal Early’s Confederate army, and the subsequent resistance by Emory’s troops from their Union rifle-pit positions, 19 October 1864 (public domain).

It was during the fall of 1864 that Major-General Philip Sheridan began the first of the Union’s true “scorched earth” campaigns, starving the enemy into submission by destroying Virginia’s crops and farming infrastructure. Viewed through today’s lens of history as inhumane, the strategy claimed many innocents — civilians whose lives were cut short by their inability to find food. This same strategy, however, almost certainly contributed to the further turning of the war’s tide in the Union’s favor during the Battle of Cedar Creek on 19 October 1864. Successful throughout most of their engagement with Union forces at Cedar Creek, Early’s Confederate troops began peeling off in ever growing numbers to forage for food, thus enabling the 47th Pennsylvania and others under Sheridan’s command to rally.

From a military standpoint, it was another impressive, but heartrending day. During the morning of 19 October, Early launched a surprise attack directly on Sheridan’s Cedar Creek-encamped forces. Early’s men were able to capture Union weapons while freeing a number of Confederates who had been taken prisoner during previous battles — all while pushing seven Union divisions back. According to Bates:

When the Army of West Virginia, under Crook, was surprised and driven from its works, the Second Brigade, with the Forty-seventh on the right, was thrown into the breach to arrest the retreat…. Scarcely was it in position before the enemy came suddenly upon it, under the cover of fog. The right of the regiment was thrown back until it was almost a semi-circle. The brigade, only fifteen hundred strong, was contending against Gordon’s entire division, and was forced to retire, but, in comparative good order, exposed, as it was, to raking fire. Repeatedly forming, as it was pushed back, and making a stand at every available point, it finally succeeded in checking the enemy’s onset, when General Sheridan suddenly appeared upon the field, who ‘met his crest-fallen, shattered battalions, without a word of reproach, but joyously swinging his cap, shouted to the stragglers, as he road rapidly past them – “Face the other way, boys! We are going back to our camp! We are going to lick them out of their boots!’”

Sheridan Rallying His Troops, Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, 19 October 1864 (U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

The Union’s counterattack punched Early’s forces into submission, and the men of the 47th were commended for their heroism by General Stephen Thomas who, in 1892, was awarded the Medal of Honor for his own “distinguished conduct in a desperate hand-to-hand encounter, in which the advance of the enemy was checked” that day. Bates described the 47th’s actions:

When the final grand charge was made, the regiment moved at nearly right angles with the rebel front. The brigade charged gallantly, and the entire line, making a left wheel, came down on his flank, while engaging the Sixth Corps, when he went “whirling up the valley” in confusion. In the pursuit to Fisher’s Hill, the regiment led, and upon its arrival was placed on the skirmish line, where it remained until twelve o’clock noon of the following day. The army was attacked at early dawn…no respite was given to take food until the pursuit was ended.

Once again, the casualties for the 47th were high. Sergeant William Pyers, the C Company man who had so gallantly rescued the flag at Pleasant Hill was cut down and later buried on the battlefield. Even Perry County resident and Regimental Chaplain William Rodrock suffered a near miss as a bullet pierced his cap.

Following those major engagements, the 47th was ordered to Camp Russell near Winchester from November through most of December. Rested and somewhat healed, the 47th was then ordered to outpost and railroad guard duties at Camp Fairview in Charlestown, West Virginia five days before Christmas.

1865 — 1866

Still stationed at Camp Fairview in West Virginia as the New Year of 1865 dawned, members of the regiment continued to patrol and guard key Union railroad lines in the vicinity of Charlestown, while other 47th Pennsylvanians chased down Confederate guerrillas who had made repeated attempts to disrupt railroad operations and kill soldiers from other Union regiments.

Assigned in February 1865 to the Provisional Division of the 2nd Brigade of the U.S. Army of the Shenandoah, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers continued to perform their guerrilla-fighting duties until late March, when they were ordered to head back to Washington, D.C., by way of Winchester and Kernstown, Virginia.

Joyous News and Then Tragedy

Spectators gather for the Grand Review of the Armies, 23-24 May 1865, beside the crepe-draped U.S. Capitol, flag at half-staff after the assassination of President Abraham Lincoln (Matthew Brady, U.S. Library of Congress, public domain).

As April 1865 opened, the battles between the Army of the United States and the Confederate States Army intensified, finally reaching the decisive moment when the Confederate troops of General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on 9 April.

The long war, it seemed, was finally over. Less than a week later, however, the fragile peace was threatened when an assassin’s bullet ended the life of President Abraham Lincoln. Shot while attending an evening performance of Our American Cousin at Ford’s Theatre on 14 April 1865, he died from his head wound at 7:22 a.m. the next morning.

Shocked, and devastated by the news, which was received at their Fort Stevens encampment, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were given little time to mourn their beloved commander-in-chief before they were ordered to grab their weapons and move into the regiment’s assigned position, from which it helped to protect the nation’s capital and thwart any attempt by Confederate soldiers and their sympathizers to re-ignite the flames of civil war that had finally been stamped out.

So key was their assignment that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were not even allowed to march in the funeral procession of their slain leader. Instead, they took part in a memorial service with other members of their brigade that was officiated by the 47th Pennsylvania’s regimental chaplain, the Reverend William D. C. Rodrock.

Unidentified Union infantry regiment, Camp Brightwood, Washington, D.C., circa 1865 (public domain).

Present-day researchers who read letters sent by 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers to family and friends back home in Pennsylvania during this period, or post-war interviews conducted by newspaper reporters with veterans of the regiment in later years, will learn that the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were collectively heartbroken by Lincoln’s death and deeply angry at those whose actions had culminated in his murder. Researchers will also learn that at least one member of the regiment, C Company Drummer Samuel Hunter Pyers, was given the high honor of guarding President Lincoln’s funeral train, while other members of the regiment were assigned to guard duty at the prison where the key assassination conspirators were being held during the early days of their imprisonment and trial, which began on 9 May 1865. The regiment was headquartered at Camp Brightwood during this period.

Attached to Dwight’s Division of the 2nd Brigade of the Department of Washington’s 22nd Corps, the 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers were permitted to march in the Union’s Grand Review of the National Armies, which took place in Washington, D.C. on 23 May.

Reconstruction

Ruins of Charleston, South Carolina as seen from the Circular Church, 1865 (U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, public domain).

On their final southern tour, Corporal Harrison Guth and his fellow 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers served in Savannah, Georgia in early June. Assigned again to Dwight’s Division, this time they were attached to the 3rd Brigade, Department of the South. Relieving the 165th New York Volunteers in July, they quartered in the former mansion of the Confederate Secretary of the Treasury. Duties for the 47th during this phase were Provost (military police) and Reconstruction-related, including rebuilding railroads and other key segments of the region’s battered infrastructure.

Beginning on Christmas day of that year, Corporal Guth and the majority of 47th Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers, finally began to honorably muster out for the final time in Charleston, South Carolina — a process which continued through early January. Following a stormy voyage home, they disembarked in New York City. Weary, but eager to see their loved ones, they were transported to Philadelphia by train where, at Camp Cadwalader on 9 January 1866, they were officially given their honorable discharge papers.

Still owed one hundred and forty-two dollars of the two hundred and sixty-two dollars that the federal government had promised to pay him as a “bounty” for joining the Union Army, Corporal Guth was not actually paid that full amount at the end of his military career because he still owed eleven dollars to the sutler for supplies he had purchased to make his war-torn life a bit more bearable while in service to the nation.

Return to Civilian Life

Following his honorable discharge from the military, Harrison Guth returned home to Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, where he subsequently wed fellow Pennsylvanian Martha A. Reinert (1846-1913), who was a daughter of Reuben Reinert (1816-1885) and Maria (Derr) Reinert (1813-1888).

Together, they welcomed the Lehigh County births of: Clara J. P. Guth (1879-1918), who was born on 28 September 1870 and later wed Frank C. M. Bortz (1869-1919); George Franklin Guth (1873-1951), who was born in North Whitehall Township on 3 January 1873 and later wed Gertie E. Heilman (1879-1969); Albert William Guth (1875-1938), who was born in South Whitehall Township on 24 February 1875 and later wed and was widowed by Ellen L. Werley (1875-1896), before marrying Katie R. Bortz (1882-1970); and Francis Martin Good (1879-1931), who was born on 25 January 1879 and later wed Jennie Katie Roth (1882-1975).

By 1880, Harrison Guth was a laborer residing in North Whitehall Township with his wife, Martha, and their children: Clara J. P., George Franklin, Albert William, and Francis Martin Good.

Allentown Militia, Soldiers and Sailors Monument Dedication, Allentown, Pennsylvania, 1899 (public domain).

Nineteen years later, on 19 October 1899 — the thirty-fifth anniversary of the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, Harrison Guth and his fellow American Civil War veterans participated a spectacle like none other. That day, as many as fifteen thousand veterans, musicians, civic officials, school children, and others lined up for a parade that made its way through the streets of Allentown to the city’s Center Square, as part of the Dedication Day ceremonies for the Lehigh County Soldiers and Sailors Monument. The events were witnessed by more than forty thousand people. (The monument still stands today.)

Still residing in North Whitehall Township after the turn of the century, Harrison Guth worked as a day laborer to support his wife, Martha, and their son, Francis Martin Good, who was also employed as a day laborer.

By 1910, he and his wife were “empty nesters” who lived by themselves in North Whitehall Township. Harrison Guth. A seventy-one-year-old laborer, he performed “odd jobs” to support his wife of forty-one years. Both spoke only German, according to that year’s federal census.

But their time together was winding down.

Illness, Death and Interment

Original gravestone of Corporal Harrison Guth, Company G, 47th Pennsylvania Volunteers, Jordan Lutheran Cemetery, Orefield, Lehigh County, Pennsylvania (courtesy of Deb C., used with permission).

On 9 March 1912, Harrison Guth suffered an episode of apoplexy, which ultimately ended his life four days later. Following his death at the age of seventy-three in North Whitehall Township, on 13 March 1912, he was laid to rest at the Jordan Lutheran Cemetery in Orefield, Lehigh County.

What Happened to Harrison Guth’s Widow and Children?

Following her husband’s death, Martha (Reinert) Guth continued to reside at their home near Siegersville in Lehigh County. Ailing with cancer, she died just over a year after her husband’s passing. Nearly sixty-seven years old at the time of her death, which occurred at her home on 1 April 1913, Martha A. (Reinert) Guth was laid to rest beside her husband at the Jordan Lutheran Cenetery in Orefield. In addition to her four children, she was survived by two brothers: Alfred Reinert, of Coplay; and William Reinert, of Northampton.

Following her marriage to Frank C. M. Bortz, Harrison Guth’s daughter, Clara J. P. Guth (1879-1918), settled with him in Lehigh County, where they welcomed the births of: Edgar M. Bortz (1894-1960), who was born in Heidelberg Township, Lehigh County on 30 January 1894 and later wed Emma Knappenberger (1899-1984); Maude H. M. Bortz (1895-1965), who was born on 14 September 1895 and later wed Adam I. Schuler (1882-1963); Florence Martha E. Bortz (1897-1967), who was born in Upper Macungie Township, Lehigh County on 1 November 1897 and later wed and was widowed by Charles Augustus Conrad (1887-1940), before she wed and was widowed by George E. Mest (1893-1947), before being married for the final time to Harvey Ambrose Shaner (1896-1973); Robert F. Bortz (1902-1965), who was born on 13 February 1902 and later wed Sallie D. Baer (1905-1960); Ellen J. M. Bortz (1903-1918), who was born on 1 March 1903 but died at the age of fifteen, on 24 October 1918, after falling ill with the flu and pneumonia during that year’s Spanish Influenza epidemic; and Daisy E. Bortz (1907-1974), who was born in North Whitehall Township on 28 May 1907 and later wed Arnold Harold Kapp (1907-1976). Tragically, three days after the death of her teenaged daughter (Ellen), Clara J. P. (Guth) Bortz also died from pneumonia. Just forty-eight years old at the time of her passing at her home in Hillside, Lehigh County, on 27 October 1918, she was memorialized with her daughter during a double funeral service on 30 October, and was then laid to rest beside her daughter at the Jordan Lutheran Cemetery in Orefield, Lehigh County.

Following his marriage to Jennie Katie Roth, Harrison Guth’s son, Francis Martin Guth, Sr. (1879-1931), settled with her in Lehigh County, where they welcomed the births of: Lawrence H. Guth (1901-1986), who was born on 15 November 1901 and later wed Rosa Ruth Weber (1904-2000) and worked for the Trojan Powder Company in Allentown; Stella Mae Guth (1903-1921), who was born on 5 June 1903 and later wed Robert Franklin Laudenslager (1904-1988); Mabel E. Guth (1905-1994), who was born on 11 March 1905 and later wed Elias Zettlemoyer (1899-1979) and worked for Katos Sportswear in Kutztown, Berks County; Charles Walter Guth (1907-1985), who was born in South Whitehall Township on 27 March 1907 and later wed Florence M. Hilbert (1905-1982) and became the owner-operator of Guth’s Economy Store and Meat Market in Trexlertown; Franklin G. Guth (1909-1972), who was born in Whitehall on 7 July 1909 and later wed Marguerite I. Wagner (1914-1991) and worked for Zimmerman’s Market in Allentown; Esther V. Guth (1912-1970), who was born in 1912 and later wed Elmer Howard Hunsicker (1904-1965) and worked for Grant’s Department Store in Allentown; Llewellyn Nathan Guth (1914-1988), who was born in Orefield on 29 July 1914 and later wed Helen Mabel Gaumer (1914-1996) and worked as a butcher at the N. T. George Butcher Shop in Orefield; Hilda A. Guth (1920-2016), who was born in Orefield on 14 January 1920 and later wed and was widowed by Earl Ray Frederick Cunningham (1914-2009); Bessie Edna Guth (1922-2017), who was born in Allentown on 21 March 1922 and later co-owned the Maidencreek Orchards in Maidencreek Township, Berks County with her husband, Henry Sterling Krumanocker (1917-1996); and Francis Martin Guth, Jr. (1927-1983), who was born in Orefield on 30 November 1927. Residing near Siegersville, Orefield during his final months, Francis Martin Guth, Sr. contracted pneumonia and was hospitalized in Allentown, where he died at the age of fifty-two on 16 September 1931. Following funeral services, he was also buried at the Jordan Lutheran Cemetery in Orefield.

Following his marriage to Ellen L. Werley during the late summer or fall of 1895, Harrison Guth’s son, Albert William Guth (1875-1938), was widowed by her just months later when she passed away at the age of twenty in Lehigh County, on 22 March 1896. After marrying a second time — to Katie R. Bortz (1882-1970) on 7 May 1898, Albert W. Guth then welcomed the Lehigh County births with her of: Ralph Raymond Guth (1898-1976), who was born in Orefield on 17 October 1898; Minnie Guth (1902-1927), who was born in Egypt, Lehigh County on 27 December 1902 and later wed Leon Rumfield, but died from pregnancy-related complications on 22 September 1927; and Esther Alverta Guth (1906-1906), who was born in Egypt, Lehigh County on 20 June 1906 but died just over a month later in Whitehall on 2 August of that same year. A farmer during his early adult years, Albert W. Guth worked at a cement plant during the early 1900s and then briefly returned to farming circa 1920, before accepting a job at the Fogelsville, Lehigh County plant of the Lehigh Portland Cement company in 1924. Ailing with diabetes during the final years of his life, Albert William Guth died at the age of sixty-three at his home in Fogelsville, on 21 March 1938, and was also interred at the Jordan Lutheran Cemetery in Orefield.

Following his marriage to Gertie E. Heilman, Harrison Guth’s son, George Franklin Guth (1873-1951), welcomed the births of: Bertha M. Guth (1899-1991), who was born in South Whitehall Township on 13 April 1899 and later wed Henry F. Haas; and Russell Norman Guth (1913-1986), who was born in Allentown on 20 July 1913 and later wed Mae M. Miller (1920-2003). After a full life, George Franklin Guth died at the age of seventy-eight in Upper Macungie Township, Lehigh County, on 8 November 1951, and was also buried at Orefield’s Jordan Lutheran Cemetery. According to his obituary in Allentown’s Morning Call newspaper:

Guth, a native of North Whitehall Township, had operated a truck and turkey farm until his retirement in 1948 because of ill health. For 17 years he had been school bus driver for Upper Macungie Township, operating the Fogelsville grade school bus.

What Happened to the Siblings of Harrison Guth?